Take photos of your garden, if possible from the same place each time, to visually monitor the changes. You’ll be astonished at the differences over time.

Take photos of your garden, if possible from the same place each time, to visually monitor the changes. You’ll be astonished at the differences over time.Measuring Success

It’s always reassuring to know that the things you do are having the effect you desire, and with gardening for wildlife that means doing some kind of recording.

Some of us have a natural tendency to want to catalogue, compare and analyse what is going on – if so, this section is right up your street. Even if you are normally allergic to surveys, I hope you’ll try some of the quick ideas in the starter level, because the benefits of monitoring are huge.

Not only can it give you confidence and satisfaction that things are improving under your watch, but you can also contribute your data to national surveys. It is through these that we have been able to spot changes in garden wildlife populations – such as the decline of Song Thrushes, Starlings and House Sparrows – and so do something to remedy them.

I’ve recorded my garden wildlife pretty assiduously for 16 years now, and the results have amazed me. What is most revealing is how flawed my memory is! Where I might previously have sworn that a species was now commoner or rarer than before, I find the data often tells a very different – and I now realise a far more accurate – story.

Starter-level monitoring

Take photos of your garden, if possible from the same place each time, to visually monitor the changes. You’ll be astonished at the differences over time.

Take photos of your garden, if possible from the same place each time, to visually monitor the changes. You’ll be astonished at the differences over time.

Take part in the annual RSPB Big Garden Birdwatch. For one hour only during the last weekend in January, count the maximum number of each species that visits your garden, and enter your results online along with half a million other people.

Take part in the annual RSPB Big Garden Birdwatch. For one hour only during the last weekend in January, count the maximum number of each species that visits your garden, and enter your results online along with half a million other people.

Keep an annual list of the species of birds and butterflies that visit your garden.

Keep an annual list of the species of birds and butterflies that visit your garden.

Keep a wildlife gardening diary and write about what you’ve seen and how you feel.

Keep a wildlife gardening diary and write about what you’ve seen and how you feel.

My recording sheets just sit on the windowsill. Every time I see a bird, butterfly or dragonfly, it takes only a second to scribble it in. Over time, the sheets become a fascinating record of the changing visitors to my garden.

Intermediate-level monitoring

Try the British Trust for Ornithology’s Garden Birdwatch. There’s a small annual fee, and each week you record the maximum number of each species that you see in your garden. You then enter your records online or send them in, and it gives the BTO (and you) a fascinating insight into how birds use gardens year-round.

Try the British Trust for Ornithology’s Garden Birdwatch. There’s a small annual fee, and each week you record the maximum number of each species that you see in your garden. You then enter your records online or send them in, and it gives the BTO (and you) a fascinating insight into how birds use gardens year-round.

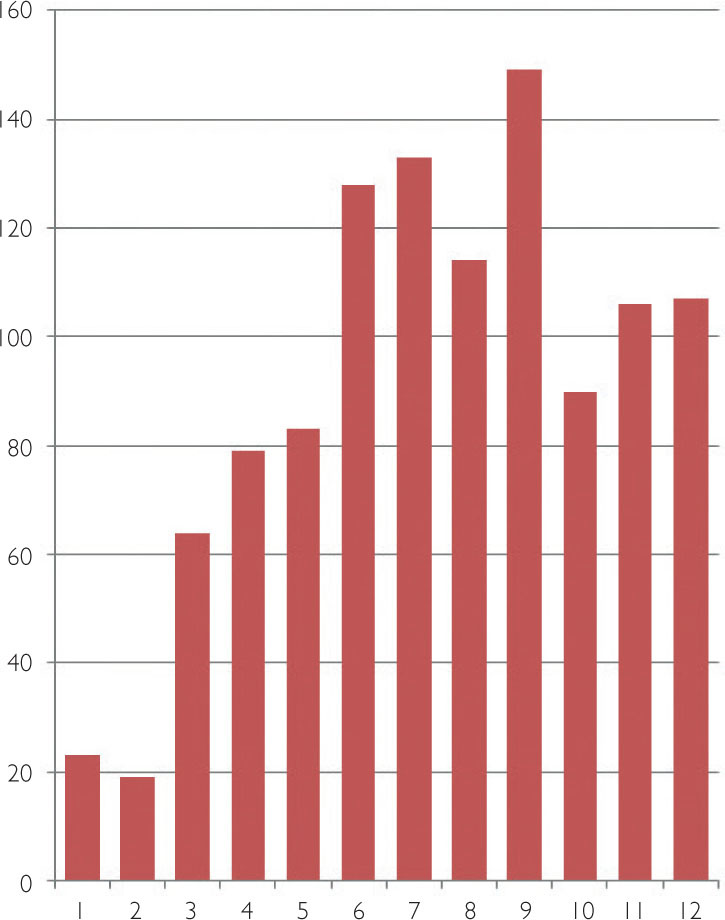

The graph shows butterfly numbers in my garden recorded over a 12-year period. The totals are the maximum number of each species seen each week, added up for each year. Numbers rose quickly at first after I planted the right flowers, then dropped a little as my garden became shadier.

Moth trapping is a great activity to take to friends’ gardens as an after-dinner entertainment. In my experience, they are always amazed when a previously hidden world of wildlife is revealed in their own backyard.

With a night-vision trail cam, you can get an idea of what secret activity takes place under cover of darkness in your garden.

Advanced-level monitoring

Moth trapping

You will have noticed that many moths are attracted to light with what looks like a death wish. Why they do it is still poorly understood, but it is part disastrous (they are distracted from mating and feeding by all our street and house lights, and they get picked off under them by enterprising bats) and part fortuitous (because we can use special light traps to monitor which species are about and measure how well they are doing).

With a moth trap, the moths fly towards the light then are deflected into a collection area, where they hunker down in special resting bays (egg boxes). ‘Moth-ers’ (not to be confused with mothers) then either identify and count them at night using a torch or wait until the following morning, after which the moths are released unharmed. You’ll be amazed by what you catch!

Two types of light are widely used: a fluorescent (actinic) tube that only gives off a vague blue light to human eyes and a more powerful mercury-vapour (MV) bulb that will illuminate half a street but will quadruple the number of moths you catch. There are three main types of trap:

The Heath Trap uses a vertical actinic light, in the middle of three perspex ‘wings’ that guide moths into a collecting basin.

The Heath Trap uses a vertical actinic light, in the middle of three perspex ‘wings’ that guide moths into a collecting basin.

The Skinner is a square wooden trap with either an actinic or MV light and two sloping perspex panels to guide the moths into the heart of the trap.

The Skinner is a square wooden trap with either an actinic or MV light and two sloping perspex panels to guide the moths into the heart of the trap.

The Robinson trap is a robust round ‘bin’ with a perspex collar and an MV light.

The Robinson trap is a robust round ‘bin’ with a perspex collar and an MV light.

Bat detectors

Bat detectors convert a bat’s squeaks into clicking sounds we can hear and show what frequency the noise is. Because different species squeak at different frequencies, we can then work out what species is nearby. Well, it’s almost that simple! Those who like gadgets will love it, and in the absence of you holding a bat licence for inspecting roosts and bat boxes, it’s one of the few ways to get a better understanding of your garden’s bats. Prices will vary depending on the model.

Pitfall trapping

To trap monsters on the prowl, try this minibeast version of the jungle explorer’s bear trap. Take a plastic drink cup, skewer some holes in the base, sink it into the soil so that its lip is level with the soil surface and cap it with a flat stone raised a couple of inches on some pebbles to keep the rain out. Unsuspecting beetles that scuttle past drop in and can’t get out. Check your catch early each morning before some of your captives eat each other!

Bird ringing brings physical contact with birds that you don’t normally get which, when the bird is something such as this Sparrowhawk, is especially exciting.

Bird ringing

This is really specialist territory now. Bird ringers need to train for years under the guidance of a guru to get a licence before being let loose. Bird ringing involves slinging a very fine, vertical mist-net across a well-used flight path and waiting for birds to fly into it. Birds are carefully extracted, have a uniquely numbered metal ring put on one of their legs, then are aged, measured and logged before being released.

The hope is that someone somewhere else at some future date will re-trap the bird, allowing us to see how far it has moved and how long it has lived. Data collected in this way has been jaw-dropping. It is only through ringing, for example, that we know British Swallows winter in South Africa and our wintering Blackcaps come from Germany. Check out www.bto.org for more information on how to become a ringer.