4

My Way

Control (and the Controlling

Control Freaks Who Need It)

The artist as control freak? Thanks to the ubiquity of twenty-first-century media, the tirades of controlling artists are more publicly accessible than ever. Log onto YouTube and you can revisit Christian Bale as he lambastes a cinematographer for ruining a scene or watch David O. Russell and Lily Tomlin lock horns on the set of I Heart Huckabees. But tales of headstrong artists jostling for control over their work did not originate in modern-day Hollywood. Consider that, more than a century ago, the Russian playwright Anton Chekhov fought constantly with the famed director Konstantin Stanislavski over the interpretation of his plays. Chekhov saw them as comedies; Stanislavski, as dramas. Often, the former felt his work was mangled beyond recognition. “All I can say is that Stanislavski has wrecked my play,” Chekhov said of The Cherry Orchard, now among his most cherished masterpieces, when it first opened in 1904. Stanislavski, likewise, had harsh words for Chekhov’s ability to play nice, calling him “stern, implacable, and absolutely uncompromising over artistic issues.” Theater scholars have since come to appreciate both comedic and dramatic renditions of Chekhov’s plays, suggesting that the two men were equally hard headed. But then that’s one of the great things about art: It allows us to take pleasure in the creative labors of narrow-minded people whom, in real life, we would probably hate.

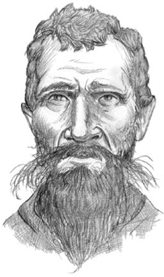

Anton Chekhov

So what happens when tenacity and vision meet obstinacy and arrogance? Frequently, the results can be overindulgent. Give an artist too much creative control, and the next thing you know, Kill Bill is two movies. Then again, a controlling presence is not always detrimental to the project at hand. As we’ll see with the following case studies, a healthy dose of bull-headedness can go a long way in creating a masterwork—or ten. Only hindsight can tell us if an artist’s immutable vision is truly justified, but it’s safe to say that any masterpiece worth making requires a strong, if inflexible, personality to see it through.

(1475–1564)

Abstract: Anything you can do, I can do better

Birth name: Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni

Birthplace: Caprese, Tuscany, Italy

Masterwork: The ceiling of the Sistine Chapel

Demons: Terminal one-upmanship

“No painting or sculpture will ever quiet my soul.”

—On his final masterpiece, The Rondanini Pietà, circa 1556

“When I returned to Florence, I found myself famous,” Michelangelo Buonarroti boasted in a diary entry, recalling the summer of 1501, when he arrived back in his adopted hometown after a successful five-year stint in Rome. He had a reason to feel cocky that year. At twenty-six, he had just completed work on a stunning new marble statue called the Pietà. The piece, depicting the freshly crucified body of Jesus cradled in his mother’s lap, was commissioned by the French Cardinal Jean de Billheres. It was no small achievement for a young artist from humble origins, the son of a small-town government official. Garnering ample acclaim throughout the region, the statue helped solidify Michelangelo’s reputation as the hottest sculptor in Italy. This kid was going places, and he knew it.

Michelangelo’s superb abilities were generating a buzz, all right, but then so was his predilection for egomaniacal behavior, which was rapidly becoming infamous within artistic and political circles. Word on the street was that you could just not work with the guy. He was rude, quick tempered, and downright unprofessional.

Even the warmongering Pope Julius II, Michelangelo’s largest patron, had trouble getting the artist to meet deadlines and contractual obligations. “You can do nothing with him!” His Holiness once griped.

As it happens, many of Michelangelo’s antisocial work habits stemmed from the fact that he was fiercely competitive with other artists. He refused to work with collaborators or apprentices, preferring instead to chisel in solitude. Shortly after the Pietà was completed, he overheard a comment by one of the Roman locals who believed the statue had been carved by a rival sculptor named Cristoforo Solari. In a fit of rage, Michelangelo, late one night, broke into the mausoleum where the statue was displayed and chiseled the unambiguous inscription, “Michelangelo Buonarroti, Florentine, made this.” Such behavior was not typically tolerated from sculptors at a time when they were considered little more than skilled laborers, but Michelangelo received more leniency than most. He was just that talented.

And yet, for all his abilities, Michelangelo still harbored the private pangs of a man who secretly felt inadequate alongside artists with more diverse achievements. As a sculptor Michelangelo was unmatched, praised the world over for the Pietà and later the statue of David. As a painter, however, he was far less proficient. And that lack of diversity put him in the shadow of older, more accomplished Renaissance men, particularly Leonardo da Vinci, a revered master of painting, sculpture, music, science, engineering, and pretty much everything else. In modern context, Michelangelo might seem a raving one-upman, a Gladwellian outlier determined to be the best at everything he tried. Back then, people probably just thought he was a self-absorbed jerk. Either way, he was ruefully tortured by the fact that artists such as Leonardo had skills that surpassed his own. In fact, it was this voracious desire for unmatched greatness that drove the creation of his most enduring masterpiece, a work that stands today as one of the defining achievements of the High Renaissance—the ceiling frescoes of the Sistine Chapel.

In 1508, Michelangelo was summoned back to Rome by Pope Julius II, who wanted to hire him for the ambitious paintings that would span the chapel ceiling. The sculptor had no experience in fresco; indeed, he had barely worked with color at all. So why would the pope entrust him with such a high-profile project—on a ceiling, no less? For that curious honor, Michelangelo could once again blame his inability to work with others. As it turns out, his Sistine Chapel gig was a setup, a scheme to ruin his reputation. The architect Donato Bramante, a colleague who had grown tired of working with the ornery artist, personally persuaded Julius II to give Michelangelo the job of the chapel ceiling. Bramante believed that Michelangelo would either turn it down or simply botch it to the point of embarrassment. What he did not count on, however, was Michelangelo’s burning need to prove himself as the world’s greatest living artist—a title he knew he could not earn without broadening his talents. He took the large-scale Sistine Chapel job knowing it would establish him as every bit the painter as he was a sculptor.

Of course, Michelangelo wasted no time commandeering the project in true Michelangelo style. Within a year, he fired most of his assistants and told the pontiff that he wanted more creative control. The pope grew impatient, as popes do, but Michelangelo could not resist getting carried away, taking the original plan from grand to grandiose. The result is a vast and intricate arrangement of biblical scenes, including the famous Creation of Adam, in which the whiskered almighty, looking like Willie Nelson on steroids, touches fingers with the first man on Earth.

The Sistine Chapel opened to the public on October 31, 1512, and Julius II died less than four months later. When it was all over, Michelangelo was nearly dead himself. He later complained of the “four tortured years” that took their toll on his body. Still, the project gave him the chance to finally prove his diversity, and as the years progressed he grew even more diverse, accomplishing feats in engineering, architecture, even poetry. Through it all, though, his obsession with his own greatness never left his mind, even as it became clear that his best years were passing him by. Mortality did not sit well with Michelangelo. The man who celebrated male potency in David grew repulsed by his aging body. He spoke of his wrinkled face, his loose teeth, and the ringing in his ears as if they were some kind of debt for his former artistic prowess. “This is the state where art has led me, after granting me glory,” he said in his final years. “Poor, old, beaten, I will be reduced to nothing if death does not come swiftly to my rescue.”

Clash of the Titans

In 1504, Michelangelo was commissioned to paint a mural in the Great Council Hall of Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio. It was a terrific honor—a battle monument to celebrate the newly reinstated Florentine republic. There was just one small problem: Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo’s greatest rival, was commissioned to paint a different mural in the same room. Now, the two men would have to work side by side, in competition, as onlookers compared and judged their respective murals. It was the paint-off of the century, an event that drew spectators from around the world. Unfortunately for anyone who expected a Herculean sporting event, the competition ended anticlimactically, cut short by the fact that Michelangelo and Leonardo, their differences notwithstanding, shared a gross tendency to procrastinate. Both artists failed to complete their murals before eventually getting roped into other projects. When the republic fell in 1512, funding for the murals fell with it.

There is something paradoxical in the thought of Michelangelo, the immortal artist, waiting around for death. One could argue that he’s still waiting. Five hundred years after it was painted, the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel still attracts some 4 million visitors every year. Even for the most restless of egos, that’s a nice little stroke.

(1923–1977)

Abstract: It’s not over until the skinny girl sings

Birth name: Maria Anna Sophia Cecilia Kalogeropoulou

Birthplace: New York, New York, USA

Peak Performance: In the title role of La Gioconda, Verona Arena, 1947

Demons: Carbs

“I was the ugly duckling, fat and clumsy and unpopular.”

—Interview with Time magazine, 1956

When dissecting the fractured and frenzied life of the legendary opera singer Maria Callas, two points must be made clear. First, the widely reported rumor that she deliberately swallowed a tapeworm to lose weight is probably untrue. Second, just because she didn’t deliberately swallow a tapeworm doesn’t mean she wasn’t crazy enough to do it. And yet if reports of her weight-loss methods were overblown, then her reputation for temper tantrums, vicious rivalries, familial discord, and failed love affairs is well earned.

Callas’s status as the quintessential diva remains unchallenged, even by Mariah Carey’s ever-increasing list of backstage demands.

The famed dramatic soprano went from stout to svelte and became the transformative prima donna of the opera world, a furniture-throwing,

litigation-happy starlet who made headlines wherever she went.

None of this is to suggest that Callas’s overt diva demeanor was not backed up by serious talent. (Pay attention, Mariah.) The extraordinary range of her voice gained her an audience of staunch devotees almost immediately following her debut in 1947, when she performed in Ponchielli’s La Gioconda at Italy’s Verona Arena. To be sure, her voice was an imperfect one, fraught with hollowness and shrills but buoyed by powerful and expressive performances. Her vivid interpretations of the roles she played made her unique at a time when other opera singers did little more than stand around and wear Viking hats. By 1953, Maria was a star. But she was larger than life in more ways than one.

Weight had always been an embarrassing issue for Maria, from her childhood in upper Manhattan through her adolescence in Athens. A rotund frump of a child, she grew up in the shadow of an outgoing and slender older sister, whom her mother groomed for marriage to the wealthiest husband she could find. For Maria, she had other plans. After recognizing the outstanding singing ability of her younger daughter, Maria’s mother hoped to keep the girl as she was, plump and awkward, so that her potential singing career would not be thwarted by the likes of a gentleman suitor. Not that suitors would be a problem. Maria spent her adolescence in a veritable social coma, watching handsome men eat out of her sister’s hand while she stayed at home binging on fatty Greek dishes and feeling repulsive to the opposite sex. To make matters worse, she apparently didn’t smell any better than she looked. Her skin was allergic to perfumes and deodorants, which made summers in Athens a particularly putrid ordeal. However, if her appearance damaged her sense of self-worth within social circles, she soon discovered her source of confidence through her tremendous voice, which earned her not only praise and admiration but also scholarships to Athenian music conservatories. When Maria’s mother urged her young daughter to pursue opera as a career, Maria agreed, but only on the condition that she one day become a “great singer.” By the time she began her vocal training, she was already declaring her ambition to perform in the world’s greatest opera houses. Not everyone believed she could achieve this goal, of course. Maria’s first teacher took one look at her round, pimply face, thick-rimmed glasses, and gnarled fingernails and dismissed her ambitions as “laughable.” But Maria did not let herself be deterred. If she could not control her weight, she could still control her destiny.

This brings us back to 1953. Maria was at the top of her game, having appeared at nearly every major opera house in Italy, but the food-loving soprano had still not conquered her greatest vice. She was pushing 200 pounds, and the gossipy magpies of the Italian opera world were starting to talk. One critic, reviewing her performance in Verdi’s Aida, joked that he could not tell Maria’s chunky legs from those of the elephant in the scene with her. The review brought Maria to bitter tears, but soon she would vow to make them all eat their hearts out.

It was when a director gave Maria an ultimatum—lose weight or else—that she finally realized enough was enough. Over the next year, Maria’s weight loss was dramatic and rapid, fueling endless speculation about how she pulled it off, including the aforementioned tapeworm rumor. The singer was, in fact, treated for tapeworms, but the worms were likely the result of her fondness for raw steak, not because she had deliberately swallowed them to shed pounds. The real story behind her methods, however, is no less bizarre. Enlisting a group of Swiss doctors, she underwent a dangerous treatment whereby she was administered large doses of thyroid extract to increase her metabolism. When that proved to be too slow a method, she had iodine applied directly to her thyroid, which melted pounds quickly but also wreaked havoc on her nervous system.

Nevertheless, by 1954, Maria had emerged the very image of beauty and glamour, captivating audiences with her newly sculpted features, intense dark eyes, and trim figure. Her elephantine legs had given way to slight calves and delicate ankles, tapered off by high-heeled shoes instead of the clumpy Oxfords she used to wear. And as she transformed, so did her wardrobe, with Europe’s top designers offering her chic gowns to wear at public functions. Maria Callas, the frumpy fat lady of opera, had enacted her revenge by becoming the very symbol of Parisian and Milanese elegance.

It’s All a Blur

Stage fright crippled Maria Callas’s performances in her early years, almost derailing her career before it started. Fortunately, she was blessed by one particular malady that helped her overcome her intense fear of performing: myopia. Severely nearsighted since childhood, Maria wore thick-lens glasses throughout her vocal training. But when she took them off, audience members became faceless blurs. No longer inhibited by the critical facial expressions of opera crowds, Maria was free to unleash the voice that would come to be known as “that voice.”

In the end, however, the change was less a butterfly-like transformation than a Faustian bargain, and her tiny new frame seemed to come with the ultimate price: the diminished power of her voice. Indeed, many of those who followed her career felt that, after 1955, Maria’s vocal ability was never the same. “When she lost the weight, she couldn’t seem to sustain the great sound that she had made,” said fellow soprano Joan Sutherland in a BBC interview. “The body seemed to be too frail.” With her voice in continual decline, Maria’s singing career was essentially over by her early forties, but her metamorphosis continues to fascinate anyone who enjoys a good duckling-to-swan fable with a bastardized twist. Since her death in 1977, countless biographies have been written about her, and she remains one of the top-selling opera artists of all time. Maria Callas may have traded talent for looks, but at least she got a legacy out of the bargain. Faust just went to hell.

(1901–1966)

Abstract: Revenge is a talking rodent wearing pants

Birth name: Walter Elias Disney

Birthplace: Chicago, Illinois, USA

Masterwork: Steamboat Willie

Demons: The knife in his back

“Born of necessity, the little fellow literally freed us of immediate worry.”

—On creating Mickey Mouse, attributed via the Walt Disney World Resort

The name Disney is synonymous with everything from family-friendly cartoons to sunny Florida vacations to the insidious homogenization of virtually every form of entertainment. Yet the namesake behind these larger-than-life manifestations was an unassuming midwestern cartoonist who would famously remind his awestruck admirers, “It all started with a mouse.” Walt Disney’s totemic rodent is easily among the world’s most recognizable symbols—right up there with the crucifix, the Buddha, and the Starbucks siren. However, it may surprise many Disneyphiles to learn that it wasn’t kind-heartedness and warm fuzzies that led to Mickey Mouse’s creation; it was good-old-fashioned anger and scorn.

Back in his pre-Mickey days, circa 1927, the young Walt Disney had already made a modest name for himself in animation circles with a cartoon critter named Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, whom he created with the help of his partner, Ub Iwerks. Oswald’s growing popularity prompted Walt to ask his boss for a pay raise. However, the young animator was taken aback when said boss, producer Charles B. Mintz, told Walt his salary was actually being decreased in an effort to cut skyrocketing overhead. When Walt refused to accept the pay cut, Mintz cut him loose and stole his entire team of animators in the process—except for Iwerks, who loyally remained at Walt’s side. Walt lost the rights to Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, who was owned by a fledgling little film outfit known as Universal Studios. Walt Disney was shocked by the betrayal and downright infuriated by the loss of his favorite character.

The young artist, who was as naive as he was stubborn, couldn’t fathom how his coworkers could so easily turn against him. Nevertheless, he vowed to bounce back, and soon he and Iwerks began to collaborate on a new character—one based on a real-life rodent that Walt would sometimes feed at his original Kansas City studio. That character became Mickey Mouse, who in turn became a sensation in November 1928 with his third film, Steamboat Willie, which was billed as the first cartoon talkie.

The experience of being stabbed in the back not only sparked the creation of Walt’s most beloved character but also the multimedia empire that remains his legacy. Upon Mickey’s success, every studio in town, including Walt’s former employer Universal Studios, was clamoring to sign the pioneering animator behind the magic. The problem? Every studio in town also insisted on retaining the rights to Mickey Mouse as part of a distribution deal. This was one concession Walt refused to make, and he opted instead to use Mickey’s success to further the reach of his own company. It didn’t matter that his company at the time comprised only three employees. Having learned his lesson from the Oswald treachery, Walt Disney made sure he retained control over everything created under the Disney name from then on. Five movie studios, seven theme parks, and six Broadway juggernauts later, it’s safe to say his control-freak tendencies paid off.

The Empire Strikes Back

In 2006, The Walt Disney Company bought the rights to Oswald the Lucky Rabbit from NBC Universal. The move came forty years after Walt Disney’s death and seventy-eight years after he originally lost the character to Universal and producer Charles Mintz in a bitter power struggle. Rest in peace, Walt.

(b. 1958)

Abstract: Frailness is not an option

Birth name: Madonna Louise Ciccone

Birthplace: Bay City, Michigan, USA

Peak Performance: Singing “Like a Virgin” atop a giant wedding cake at the first-ever MTV Video Music Awards, 1984

Demons: A frustrating inability to rule the universe

“I became an overachiever to get approval from the world.”

—Interview with Spin magazine, 1996

In the fickle world of pop music, where it’s better to burn out than fade away, Madonna has done neither. Her enduring, dance-friendly anthems exploded from the East Village club scene to become the signature sound of the 1980s and a staple of Nina Blackwood–era MTV. Her early fashion, an amalgam of thrift-store chic and post-punk frills, emerged as the default look for a generation of teen girls determined to fit as many jelly bracelets onto one arm as possible. And while a lesser artist might have been content with defining the sound and style of an entire decade, Madonna brazenly retooled her image time and again to ensure her relevance. She channeled Marilyn Monroe as the Material Girl. She spoofed Fritz Lang in Express Yourself. She infiltrated late-nineties raves with Ray of Light. What’s more, she did it all while maintaining a decades-long movie career, despite repeated pleas from Roger Ebert that she stick to music. Though her reputation for commercial shrewdness is well deserved, the true force behind Madonna’s success is a far more visceral animal: a need for power and control set into motion by a traumatic loss she suffered while growing up in small-town life in Michigan.

In 1962, Madonna’s mother, pregnant with her sixth child, was diagnosed with breast cancer—an apparent consequence of working as an x-ray technician before protective aprons were made mandatory. She delayed treatment until her baby was born, but by that time it was too late. A harrowing, yearlong battle with the disease ensued.

Madonna, then a fiery five year old whose need for the spotlight had already begun to surface, was at first confused and maddened by her mother’s waning health.

The pop star would later recall the dread she felt upon discovering how physically weak her mother had become. For the Material Girl in training, it was a defining moment, one that triggered a lifelong fear of powerlessness. “I knew I could either be sad and weak and not in control, or I could just take control and say it’s going to get better,” she told Time magazine in 1985.

Madonna spent her formative years haunted by memories of a frail and dying mother, building the ambition that would assure her success in all things. However, this overachieving fervor might never have found its true constructive purpose if not for a second childhood trauma.

In 1966, Madonna’s father, Tony Ciccone, married the family housekeeper, Joan. Since her mother’s death three years earlier, Madonna, now eight and increasingly headstrong, had formed an unusually strong attachment to her father, and she saw his second marriage as a betrayal. Joan’s entrance into the Ciccone family ignited a rebellious streak in Madonna that would punctuate her adolescence and, later, her career. The two of them, equally stubborn, played out a sort of Cinderella/Wicked Stepmother relationship, nettled by Madonna’s burgeoning need to push the boundaries of what she could say, what she could wear, and whom she could date—three facets of her life that would later make her a tabloid favorite. This bitter stepmother-daughter conflict finally came to a boil in 1978 when Madonna dropped out of the University of Michigan, where she had been attending on a dance scholarship, and left home for New York City, determined to set the world ablaze and claim her crown.

There is no denying that Madonna achieved pop-music royalty. Even her cheeky tabloid designation, Madge, is British shorthand for Your Majesty. However, she likely never would have been appointed to the court had it not been for years of childhood distress. We can only assume her early trauma was far more tormenting than anything she would experience later in life (with the possible exception of suffering through the reviews for Swept Away), but thankfully these experiences equipped her with the tools to enact change as she saw fit. More than a nonconformist, Madonna is one of those rare artists who forced the world to conform to her: hence the skirt-over-Capri-pants look, which is still acceptable to this day.

(b. 1965)

Abstract: The wizard of id

Birth name: Joanne Rowling

Birthplace: Yate, Gloucestershire, England

Masterwork: The Harry Potter series

Demons: Mortality

“No magic power can resurrect a truly dead person.”

—Interview with the Guardian, 2000

Much has been written about J. K. Rowling’s rapid transformation from state-assisted single mother to modern-day mythmaker. The deceptively humble wordsmith behind the boy wizard Harry Potter not only unleashed the most wide-reaching pop-culture phenomenon of the last fifteen years but also went on to become the first billion-dollar book author on the planet. Not bad for a former English teacher who wrote most of her debut novel in longhand at a tiny Edinburgh café during her baby daughter’s naptime. In those days, Joanne Rowling, or Jo, was still in shock from having hit rock bottom. She was unemployed, recently divorced, and struggling to support her only child on a meager seventy pounds a week. “I was the biggest failure I knew,” she said. But failure was liberating to the young writer, a means of “stripping away the inessential” and focusing solely on her craft.

In regard to her standing as a tortured artist, Jo Rowling might seem a tad too optimistic to wear the title—a resourceful coper who resolved cheerfully to shrug off poverty and finish her labor of love. And yet behind her determined exterior lies a lonely pain, one that festered in Jo’s psyche throughout her adolescence. On the eve of Harry’s birth, it exploded, only to become the very thing that gave him his soul.

In 1990, on a delayed train from Manchester to London, the idea of a black-haired boy who learns he’s a wizard first popped into Jo’s head. She was not carrying a pen at the time, and being shy around strangers, she could not bring herself to ask for one. Instead, the twenty-five year old sat silently among the other commuters, dreaming up the various characters and creatures that she thought might inhabit her wizard’s fanciful universe. That night she eagerly began writing what would become Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, the first in the seven-book series, but those first few pages bore little resemblance to the capacious and clear-minded allegory that would one day cast a spell over Millennials the world over. Jo’s story needed focus; her fertile imagination was pulling her in too many directions. Even more frustrating was the fact that her story arc lacked a singular theme—something both universal and grand to infuse the ambitious concept with the import it deserved. It wouldn’t be long, however, before the thematic world of Harry Potter would become tragically cemented by the news that Jo’s mother, Anne, lost her ten-year battle with multiple sclerosis. It was the most devastating shock of Jo’s life.

It’s not that Jo had been oblivious to her mother’s failing health. Since the age of fifteen, she had watched helplessly as Anne gradually lost her ability to perform everyday tasks, her body rebelling against itself in disrepair. But Jo had somehow managed to convince herself that the condition was not as serious as it appeared. The girl who would one day conjure up Quidditch games and cauldron cakes had such an inherent knack for fantasy that her instinct was to deny the inconceivable reality. Death, while imminent, was simply too painful to consider. “I don’t know how I didn’t realize how ill she was,” she said in an interview, recalling the last time she’d seen Anne alive, thin and exhausted. It was during that final visit that Jo adopted her now-famous tight-lipped policy in regard to projects in development. She never told her mother about the fantastic idea gestating in her head, the wizard named Harry who at the time was nothing more than a scrawl of notes. Soon it would be too late. Anne passed away in December 1990, only a few months after Harry’s conception. The death of Jo Rowling’s mother unleashed nascent controlling tendencies buried within Jo’s emotional interior.

Like Madonna, whose own mother’s death filled her with a lifelong fear of powerlessness, Jo became overwhelmed by the realization that fate can deal us a fatal blow at any time. Yet the ways in which these two artists fed their quests for control could not have been more different. The material girl, as we recall, fled to New York and set out to dominate the material world. But Jo turned her pursuits inward, tunneling ever deeper into a universe populated by witches, warlocks, and the occasional house elf. In the real world, Jo was a powerless Muggle who could do nothing as her mother succumbed to an insidious disease. In the imaginary world of Harry Potter, however, there were no limits to Jo’s power, and the writer gave herself carte blanche to fashion a reality that suited her. It was her creation, governed by her logic.

Peppered liberally throughout the Potterverse is constant evidence of Jo’s pain and isolation. (Consider the Dementors, the soul-sucking

fiends that feed on human happiness, inspired by Jo’s draining bout with clinical depression.) Yet despite the magic and fantasy of Harry’s reality, Jo saddled her creation with one sobering truth that mirrors our own: The characters, be they warlocks, wizards, or what have you, cannot cheat death. “Once you’re dead you’re dead,” she said bluntly of her characters’ mortality.

As death emerged as the chief theme of the Harry Potter series, it became keenly reflected in the life of its bespectacled protagonist. As a baby, Harry’s parents are murdered by the evil Voldemort, a Dark Lord whose obsession with immortality is shared by the author herself. “I so understand why Voldemort wants to conquer death,” she admitted. “We’re all frightened of it.”

The death of J. K. Rowling’s mother took place just as her daughter’s greatest creation was being born. The weight of that tragedy fed the inventive young writer an unkind dose of reality, one that elevated her whimsical tale of a boy wizard by grounding it in the deepest fears of us earthbound humans.

Women’s Writes

The publishing industry has apparently not abandoned its long and tiring history of hiding the gender of female writers. In 1997, when the first Harry Potter book was nearing publication, Rowling’s British publisher, Bloomsbury, rightly believed that young boys would make up a sizable segment of Harry’s audience. Not wanting to alienate that demographic, Bloomsbury asked Rowling to dump her first name in lieu of two initials. Rowling, who has no middle name, picked “K” as her second initial, after her grandmother Kathleen. Her unisex byline puts her in the company of countless female authors, including—to name a few—Charlotte Brontë, who published Jane Eyre under the gender-neutral name Currer Bell, and Mary Shelley, who published Frankenstein anonymously. Perhaps the most obvious Rowling comparison is Susan Eloise Hinton, whose publisher urged her to use her initials out of fear of alienating a presumably male audience for her debut novel, The Outsiders.

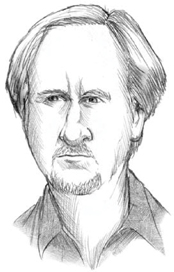

(b. 1954)

Abstract: Opening Pandora’s box

Birth name: James Francis Cameron

Birthplace: Kapuskasing, Ontario, Canada

Masterwork: Avatar

Demons: Idleness

“There are going to be little windows of opportunity that open for a split second, and you either squirt through or you don’t.”

—Interview with the Academy of Achievement, 1999

For irrefutable evidence of our one-time willingness to overlook cheesy special effects, consider Logan’s Run, the 1976 film that takes plastic egg cartons and tries to pass them off as an advanced bubble city of the twenty-third century. That the film earned an Academy Award for its visual efforts says less about its ability to blow the minds of seventies moviegoers and more about the fact that Hollywood, in those days, simply had nothing better to offer.

James Cameron, a young truck driver and community college dropout living in Southern California, thought he could do better, although he had no idea how he might pull it off. He spent much of his spare time scribbling down ideas for stories set on alien worlds and in distant galaxies—ideas that Hollywood had yet to effectively conceptualize—but in reality he was just another no-name kid with a drawer full of unfinished scripts.

Then, in the summer of 1977, James went to see a sci-fi adventure movie called Star Wars, and as he watched the film’s fantastic space battles unfold on screen, a wave of humility choked him. When it was over, he was left with a maddening realization: This was the movie he should have made. He had spent years passively dreaming up stories in his head while a fellow Southern Californian named George Lucas—only ten years his senior—went out and created a groundbreaking achievement in visual effects. (Watch Star Wars next to Logan’s Run, and you will not believe that the two films were released only a year apart.) James left the theater that day in a fury of self-defeat, wounded by the knowledge that great ideas will not wait around for languid gestation.

That summer, as the entire country got swept up in Star Wars mania, James got swept up in his own anger. He became obsessed with figuring out exactly how Lucas brought Star Wars to the screen. He spent his spare time at the campus library of the University of Southern California, Lucas’s alma mater, where he would pore through thesis papers on special effects, front-screen projection, optical printing—anything he could find. He bought some cheap film equipment and started teaching himself how to use a camera. Teaming up with a friend, James wrote a screenplay for a space-age movie called Xenogenesis, and he managed to raise $20,000 to produce a twelve-minute segment from the film. James chose to film one of the script’s key scenes, which featured a battle between a giant robot and a woman wearing an exoskeleton. Employing his OCD-like eye for detail, he spent countless hours crafting the two miniature models he needed for the fight scene, and then he used stop-motion animation to bring the sequence to life.

When it was all finished, James hawked the segment to various Hollywood studios, hoping to convince someone to produce the full film. Unfortunately, his pitch had become all too familiar. Although California’s 1978 census report does not specify how many budding filmmakers went around that year claiming they could make the next Star Wars, James was certainly not alone. But while Xenogenesis did not land him a movie deal, his miniature models did catch the eye of Roger Corman, the consummate B-movie crackerjack, who hired James to build model spaceships for his 1980 sci-fi spectacle, Battle Beyond the Stars. From there James worked his way up the chain of visual-effects specialists until finally getting the chance to direct the film Piranha II: The Spawning. Granted, it was a low-budget camp fest about flying fish that eat human flesh, but James deftly parlayed it into an opportunity to direct a creation of his own conceiving, a film about a cyborg assassin sent back in time to kill the mother of his enemy. The enormous success of that film, The Terminator, made James a sought-after sci-fi director. He was no George Lucas, but he was on his way.

James’s fixation on minute details and technological envelope pushing became a signature trait, propelling not only his own directorial efforts but the special-effects industry as a whole. For The Terminator sequel, released in 1991, he employed then-unproven

computer-animation techniques

to create a shape-shifting assassin made out of liquid metal. The effects are not exactly eye candy by today’s standards, but they set the stage for modern computer-generated spectacles and, in an ironic twist, helped turn model making into a lost art. As James’s Hollywood dominance grew, so too did his obsession with technical perfection, which almost ended his reign.

In early 1997, when he was waist deep in production for Titanic, Hollywood was abuzz with talk of his downfall. His film was months behind schedule; it was a hundred million dollars over budget, and James was gaining a bad reputation for his dictatorial directing methods, which had him flying over Titanic’s massive sets in a crane, chewing out crewmembers with a bullhorn.

His obsession meant that by the time his film Titanic was released, James had spent an unprecedented $200 million on a three-hour movie that everyone already knew the ending to. Titanic was expected to sink faster than its eponymous ship, and James was expected to get sucked under right along with it. Of course, both proved unsinkable.

Titanic became the top-earning movie of all time, a spot it held for twelve years before it was finally toppled by another James Cameron movie. It was shortly after the release of Titanic that James conceived of a story set on a distant moon inhabited by giant blue aliens. Gone were the days when his ideas would have to collect dust in a drawer, but this time something else was standing in his way: The technology needed to film the movie did not exist yet. And just as he once spent hours building miniature models for a twelve-minute sequence, he would now spend his time developing a new camera for motion-capture animation. The result was Avatar, a 3D sci-fi fantasy that became the first movie in history to gross more than $2 billion. Monetary considerations aside, Avatar stands out for another reason: It’s one of the few films of the last decade to reach bona fide blockbuster status without the benefit of a previous tie in. In an industry that now subsists almost entirely on the recycled lifeblood of familiar superheroes and old TV shows, James’s blue-alien universe brings something fresh to the pop-culture pantheon. It’s too early to predict if his creation will have enough longevity to fuel retro treadmills of the future, but there are already two sequels in the works, and clearly Mr. Cameron will not be happy until the moon-dwelling Na’vi make a lasting impact on the mass consciousness. In interviews, he has indicated his hope that Avatar will one day exert a larger cultural influence than, say, the Star Wars franchise. It always seems to come back to beating George Lucas.