In the 1970s, Denise Schmandt-Besserat deduced that the ubiquitous small clay tokens scattered around Sumerian archaeological sites represented the precursors of the first cuneiform writing. Courtesy of Denise Schmandt-Besserat.

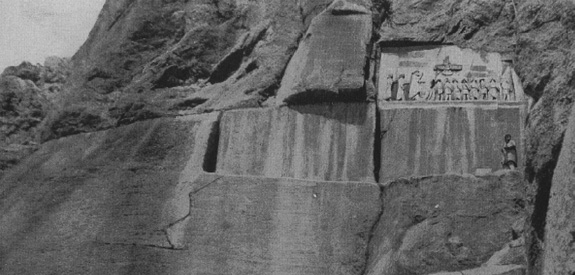

Bisitun relief: Note inscribed panels below and to the left and man at lower right panel for scale. Source: Wonders of the Past: The Romance of Antiquity and its Splendours, Sir John Alexander Hammerton, Ed., G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1924.

Drawing of Bisitun Relief: Darius gives thanks to the God Ahura Mazda for victory over the vanquished under foot and to his right. Source: Wonders of the Past: The Romance of Antiquity and its Splendours, Sir John Alexander Hammerton, Ed., G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1924.

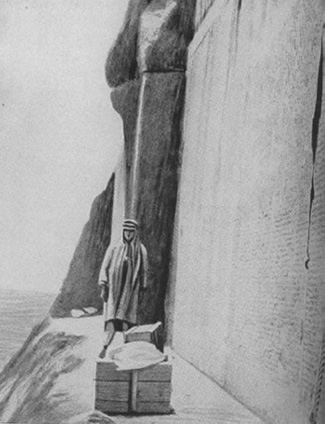

Researcher on a ledge at Bisitun inscription. Source: Wonders of the Past: The Romance of Antiquity and its Splendours, Sir John Alexander Hammerton, Ed., G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1924.

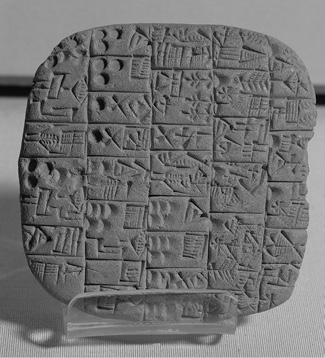

Early Sumerian sales contract for field and house, ca. 2600 BC, from Shuruppak. Note multiple circular and semicircular markings indicating numbers. Louvre, Paris, France, The Bridgeman Art Library.

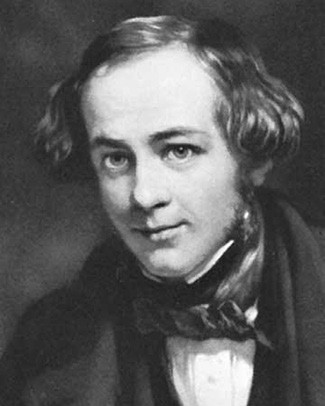

Sir Henry Rawlinson, decoder of the cuneiform inscriptions at Bisitun. Source: George Rawlinson, A Memoir of Major-General Sir Henry Creswicke Rawlinson, Longmans, Green & Co, 1898.

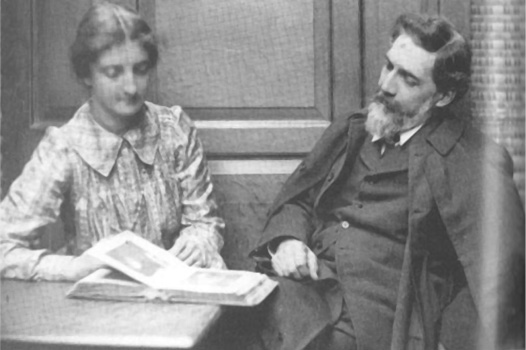

Hilda and Flinders Petrie, who came across the earliest known alphabetic script at an abandoned turquoise mine at Serabit el-Khadim in the Sinai Desert. Source: Flinders Petrie, by Margaret S. Drower, Victor Gollancz/Orion Publishing. Republication permission kindly granted by Richenda Kramer and Judy Kramer Gueive.

This birthday greeting from Claudia Severa to Sulpicia Lepidina survived in the cold, damp soil of the Vindolanda site for nearly two millennia. Note that it is written in multiple hands and has no word spacing.

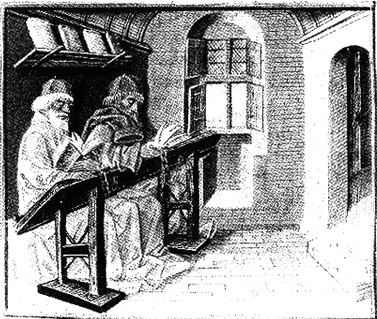

One of the first depictions of silent reading, from Jacque Le Grand’s Livre des bonnes moeurs, a mid-fifteenth century manuscript.

European papermakers were the first to add wire images to their moulds to produce identifying watermarks, such as this 1389 camel design from a French artisan.

English academic John Wycliffe, left, the Czech Jan Hus, center, and Martin Luther, right, challenged the Church’s legitimacy in the fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth centuries, respectively. Because Luther had access to the printing press, he succeeded; because Wycliffe and Hus did not, they failed.

Because of Johannes Gutenberg’s intense desire to keep secret the technology behind his invention, his only substantive historical traces lie in the legal difficulties strewed in his wake. This 1600 portrait, which hangs in Mainz’s Gutenberg Museum, is fictional. Source: Johannes Gutenberg (1398–1468) in a 16th century copper engraving; Kupferstich; 16th century, by Michael Schönitzer, Die großen Deutschen im Bilde (1936).

The complete original B42 type set used in the Gutenberg Bible. The earliest printers strove to make their books and pamphlets indistinguishable from printed manuscripts, not to make them easy to read.

Gutenberg’s Illustrator, Lucas Cranach the Elder, drew The Whore of Babylon (riding a seven-headed monster), an allusion to the corruption of the Church, from Luther’s New Testament.

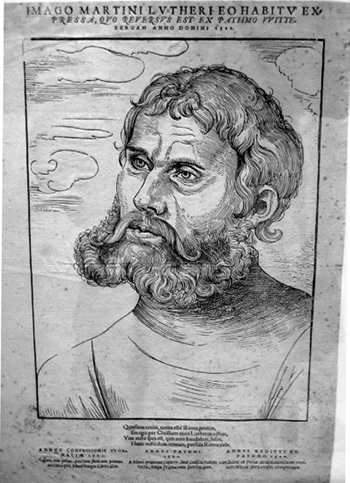

Woodcut of Luther in “captivity” at Wartburg Castle by Lucas Cranach the Elder.

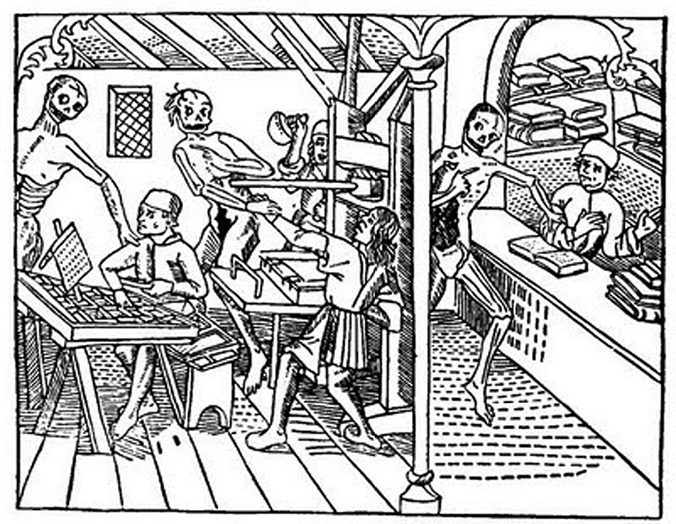

Matthias Huss’s 1499 woodcut, Danse Macabre, in which Death claims a print shop’s workers. This print provides one of the earliest—and perhaps darkest—images of Gutenberg’s invention.

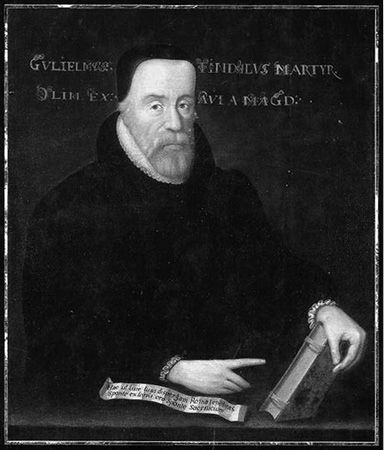

William Tyndale’s unique linguistic talents allowed him to translate the Old Testament’s well-polished original Hebrew into an English version that colors the language to the present day.

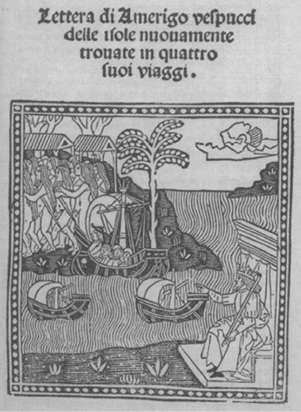

How the news traveled in 1504: Frontispiece of publication of Amerigo Vespucci’s letter to his patron Piero Solderini in Florence. At the time of the first New World voyages, Spain lay far from the center of European publishing, so news of Columbus’s discoveries did not spread widely or rapidly. Vespucci’s letters are the reason the Western Hemisphere’s continents were named after him, and not Columbus. Source: The Soderini Letter 1504 in Facsimile, (Princeton, NJ, 1916).

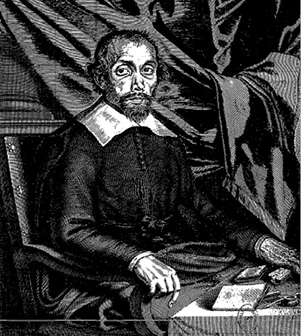

The first media tycoon: Théophraste Renaudot founded multiple Paris publications, including the groundbreaking Gazette, the People magazine of the seventeenth century.

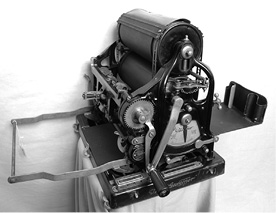

The last of the line: The all-iron, hand-operated Stanhope Press, capable of producing two hundred impressions per hour. After 1850, steam-powered high-speed presses shifted the locus of state-of-the-art printing technology from small- and medium-sized entrepreneurs like Cobbett, Hone, Carlile, and Franklin to companies large and wealthy enough to afford the expensive new technology. Republished by permission of Peter Chasseaud, Director, The Tom Paine Printing Press Museum, http://www.tompaineprintingpress.com.

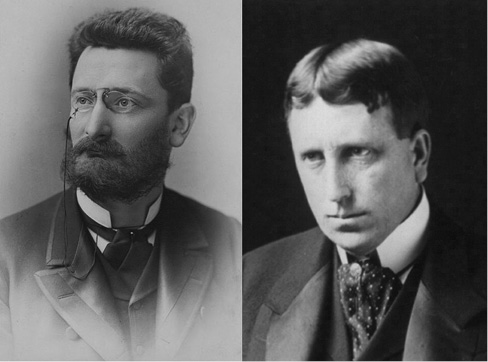

Joseph Pulitzer, left, the son of a bankrupt Hungarian grain merchant, had such poor eyesight and general health that no European army would enlist him, and so he signed on with a Union Army recruiter in Hamburg in 1864. After the Civil War, he practiced law, served in the state legislature, and eventually bought two Saint Louis newspapers, the Post and Dispatch, and later, the New York World. At Harvard, the privileged William Randolph Hearst, right, decided to emulate Pulitzer’s budding national chain.

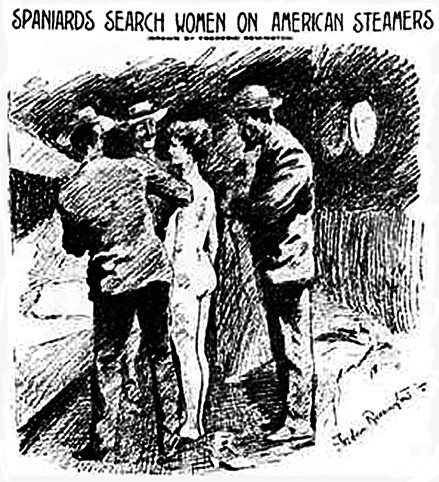

“You furnish the pictures and I’ll furnish the war.” Although Hearst’s supposed instructions were probably apocryphal, Frederick Remington carried them out to a tee with this illustration of the strip-searching of a Cuban damsel by Spanish police on the U.S.–flagged vessel. Source: “Spaniards Search Women on American Steamers.” Illustration for an article entitled “Does our Flag Shield Women?” by Richard Harding Davis. New York Journal, February 12, 1897, 1–2.

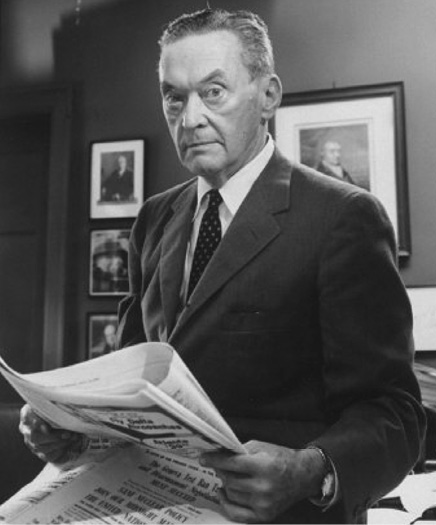

The aristocratic Walter Lippmann foresaw and encouraged the development of journalism as an honorable, objective profession, no different from the law or medicine. Source: Alfred Eisenstaedt, photographer, © 1933.

The beautiful Evangelina Cisneros, whom Hearst employee Karl Decker sprang from a Cuban prison. Hearst had her paraded in virginal white around New York, where she profusely thanked the U.S. for her freedom. The truth was less than pristine. Source: New York Journal, October 1897.

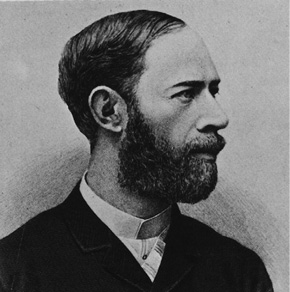

Heinrich Hertz, the physicist who devised the first radio transmitting/receiving system.

Guglielmo Marconi around 1896 with his apparatus, some of which is enclosed in a “secret box.” Source: Wireless: From Marconi’s Black-Box to the Audion, by Sungook Hong, figure of the young G. Marconi, page 37, © 2001 Massachusetts Institute of Technology, by permission of the MIT Press

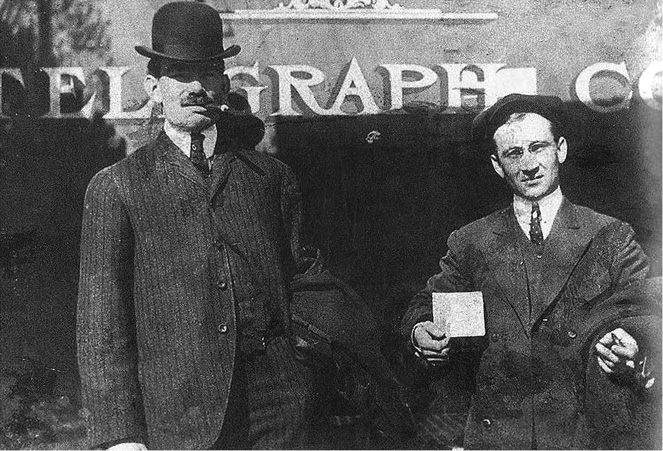

Lee de Forest (left), a brilliant electrical engineer who pushed the limits of financial propriety and patent law. Source: Empire of the Air: The Men Who Made Radio, by Tom Lewis, HarperCollins © 1992.

Transmitter in Brant Rock, Massachusetts, from which engineer Reginald Fessenden broadcast a recorded Handel aria, his own violin solo, and a Bible reading in 1906, which was heard by astounded listeners hundreds of miles away.

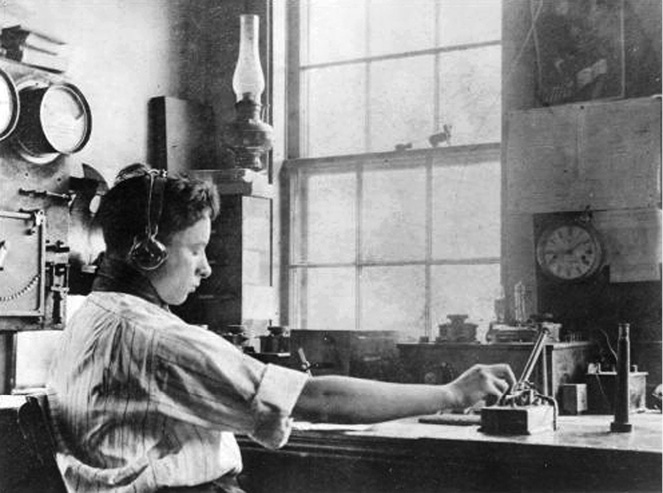

Like many late nineteenth and early twentieth century communications entrepreneurs, the young David Sarnoff started out as a telegraph operator. His first employer, the Commercial Cable Company, which fired him for observing the Jewish High Holidays. His telegraph skills then landed him a job at the Marconi Company, where he later wrote the famous “radio music box memo,” which foresaw the rise of radio as a commercial entertainment medium.

The master at work. Few contemporary politicians could match Franklin Roosevelt’s deliberate, soothing radio style, a talent that contributed in no small way to his persuasive power and four presidential electoral victories. Courtesy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library/Roosevelt Reproductions.

The bitter, cynical Joseph Paul Goebbels, at the microphone. Like Roosevelt, he grasped the persuasive power of radio early on, and made it Nazi Germany’s primary communications media. Courtesy of the German National Archives. Berlin-Lustgarten. Joseph Goebbels bei Rede von Mikrophon: Juli 1932, Photographer O. Ang.

Idealized Third Reich working-class family; note the inexpensive Volksempfänger (“people’s set”) on the right. Courtesy of the Bundesarchiv (Federal Archives of Germany), Berlin-Lustgarten. Joseph Goebbels bei Rede vor Milsrophon; July 1932, photograph by O. Ang.

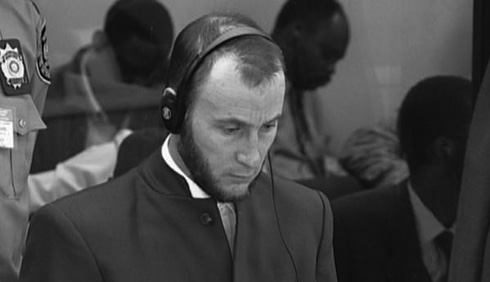

The Belgian Georges Ruggiu, incited Rwandan Hutus to murder their Tutsi countrymen over RTLM (Radio-Télévision Libre des Milles Collines). He is shown here on trial at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. Sentenced to twelve years imprisonment by the court, he was illegally released by his Italian jailers after only fourteen months.

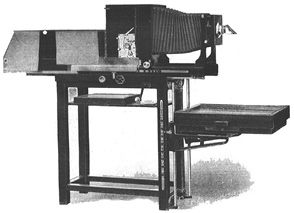

In the early and mid-twentieth century, copying could be done either on cumbersome, smelly photographic devices that produced high-quality images on expensive photographic paper, such as this 1918 Photostat machine (left), or inexpensive but low-quality images on paper with stencil devices, such as this 1950’s vintage Gestetner Duplicator (right). Source: Gestetner Duplicator from Museum of Technology, http://www.museumoftechnology.org.uk/expand.php?key=241.

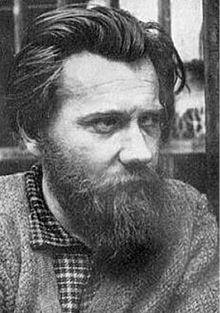

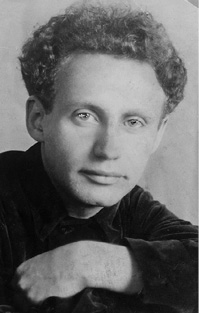

The 1966 trial of Andrei Sinyavsky, left, and Yuli Daniel, right,

illustrated how personal communications technology enabled dissident activity. Friends and family of the accused drew in foreign correspondents, whose stories were broadcast back to the USSR on the Voices, attracting yet more visitors and reporters. This process, along with smuggled tape recordings of the trial produced a daisy chain of prosecutions that undermined the legitimacy of the regime both domestically and abroad.

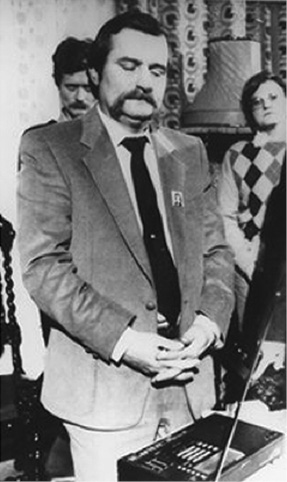

Lech Walesa learns of his 1983 Nobel Peace Prize from Radio Free Europe.

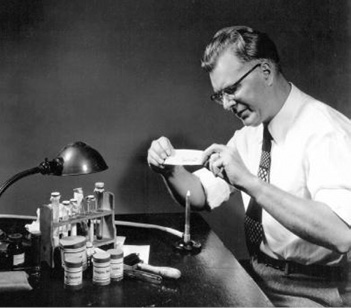

Chester Carlson reenacts the 1938 experiment in which he produced the world’s first xerographic image on plain paper, which he holds in his hand over a Bunsen burner. Courtesy of Xerox, Inc.

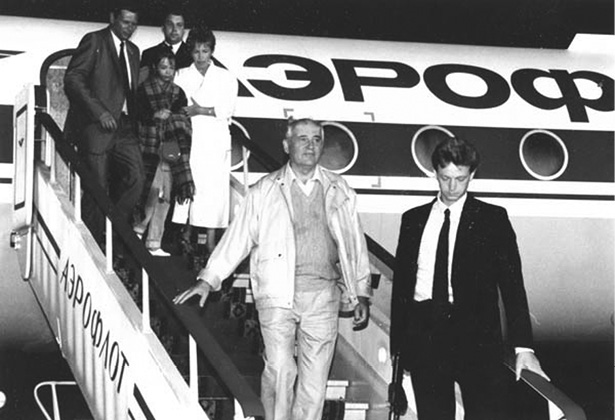

Mikhail Gorbachev and family return from Foros after the 1991 coup. The coup plotters thought that they had cut off the Soviet president from outside news at his Black Sea Villa, but they were mistaken; access to foreign radio broadcasts stiffened his resolve to resist the plotter’s demand that he resign. Source: Mikhail Gorbachev returning with his family from Foros. August, 22 1991, The International Foundation for Socio-Economic and Political Studies (The Gorbachev Foundation), Raisa Gorbachev, Biography, http://www.gorby.ru/en/gorbacheva/biography/.

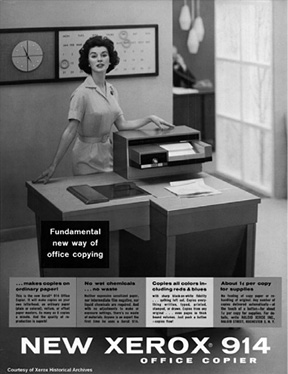

Early advertisement for the Xerox 914. Courtesy of Xerox, Inc.

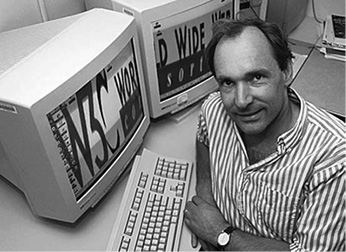

The Internet did not become a practical mass communication channel until around 1990, when Timothy Berners-Lee invented the first browser. Courtesy of the World Wide Web Consortium, Copyright © 2012 W3C ® (MIT, ERCIM, Keio).

By the mid-1990s the popular use of the Web had exploded, but navigating its exponentially increasing breadth remained problematic. Stanford grad students Larry Page and Sergei Brin (left) created an algorithm that successfully identified relevant, and usually authoritative, search results, which eventually became Google.com. Not long after, Blogger and Twitter, the creations of Evan Williams (right) surmounted the final hurdles to making the Web the world’s first two-way, mass-access communications medium. Sources: For Mssrs. Page and Brin, promotional photograph courtesy of Google, Inc.; and for Mr. Williams, http://flickr.com/photos/joi/2118601809/, December 18, 2007. Photo by Joi Ito licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License.