7

WITH A MACHETE IN ONE HAND AND A RADIO IN THE OTHER

Wars are not fought for territory, but for words. . . . Man’s deadliest weapon

is language. He is susceptible to being hypnotized by slogans as he is to

infectious diseases. And where there is an epidemic, the group-mind takes over.

—Arthur Koestler1

The ear accepts; accepts and believes.—Archibald MacLeish2

Of all the communications technologies discussed in this book, radio and television are the most hierarchical; no preceding media could reach so many people so instantaneously and with so little feedback in the opposite direction. From the outset, the near-monopoly control of these two media troubled both the public and lawmakers; in 1934 during the U.S. Congressional debate surrounding the establishment of the Federal Communications Commission, Representative Louis McFadden thundered against the “radio trust” in words that still sound fresh: “The strong hand of influence is drying up independent broadcasting stations in the United States and the whole thing is tending towards centralization of control.”3

McFadden’s concerns about the concentration of media power were well founded. As discussed in the Introduction, the advent of commercial radio around 1920 coincided with a quantifiable increase in the number of despotic governments around the world. Obviously, other factors were also at work, including the catastrophe of World War I and the subsequent global depression. Nonetheless, the triumph of the one-way media—radio and, later, television—contributed mightily to the worldwide spread of totalitarian governments in the mid-twentieth century. Even within the democratic framework of the United States, whose government, unlike those in the rest of the world, did not own or operate domestic radio stations, President Franklin Roosevelt masterfully manipulated this new medium. Elsewhere, the totalitarian effects of radio would prove much more potent.

Since prehistoric times mankind had unknowingly propagated radio waves by discharging static electricity, as occurs when a dog’s fur is rubbed on a dry winter day and sparks fly. In 1842, an American, Joseph Henry, who later became the Smithsonian Institution’s first secretary, assembled an apparatus that detected radio waves produced by a spark source thirty feet away, but scientists still lacked an overarching theory that would enable wireless electrical transmission and reception of information—that is, “radio.”

At roughly the same time, Englishman Michael Faraday was conducting experiments on the magnetic fields that surround electrical currents. In 1846, he postulated that light was a disturbance in these fields, and in 1864, his fellow countryman James Clerk Maxwell developed a theory that radio waves and light were essentially the same thing: “electromagnetic waves” differing only in their frequency and wavelength. He would develop an elegant mathematical framework—Maxwell’s equations—that described the relationships among light, magnetism, and electrical current.

The essence of science is the generation and subsequent testing of hypotheses. What separates science from pseudoscience, both premodern and New Age, is this testability; a hypothesis that makes no testable predictions is worthless. Maxwell’s equations predicted three things: that an acceleration of an electrical field, such as occurs when a spark jumps a gap, produces electromagnetic waves; that these waves travel through space; and, most astoundingly, that they do so at the speed of light. Over the prior two centuries, scientists had measured the velocity of light with increasing accuracy; since light and radio waves represented the same electromagnetic phenomena, Maxwell’s equations predicted that radio waves should travel at the same speed.4

Beautiful as Maxwell’s theory was, it lacked substantial real-world verification until German physicist Heinrich Hertz, in a series of carefully crafted experiments in the late 1880s, transmitted and received radio waves for the first time. With clever measurements and precise computations, he determined the velocity of radio waves of a known wavelength. As predicted by Maxwell, the speed of radio waves matched that of light.

Hertz produced his radio waves in so-called Leyden jars, glass containers whose inner and outer surfaces were lined with tinfoil and could hold an electrical charge (in modern terms, capacitors). These contraptions could be electrostatically charged by rubbing, as in the ancient fur-and-amber-wand technique, or, as in the case of Benjamin Franklin, by thunderstorm and kite. Both methods create the necessary sparks—hence the radio static produced by thunderstorms. Initially, these jars provided scientists with a reliable source of electricity. Hertz found that by varying the shape and size of his jars, he could also vary the wavelength produced.5

At about the same time, in England, Oliver Lodge demonstrated that antenna size affected the wavelength received; familiar with telegraphy and initially unaware of Hertz’s work, Lodge transmitted his radio waves along wires, and not through the open air, as had Hertz. It fell to his more imaginative fellow countryman, William Crookes, to realize that:

Rays of light will not pierce through a wall, nor, as we know only too well, through a London fog. But the electrical vibrations of a yard or more in wave-length [i.e., a frequency of less than 300 million hertz, or cycles per second] of which I have spoken will easily pierce such mediums, which to them will be transparent. Here, then, is revealed the bewildering possibility of telegraphy without wires, posts, cables, or any of our present costly appliances.6

In other words, the work of Lodge and Hertz had made possible what even in the late nineteenth century must have seemed a miracle: instantaneous communication not just through walls but across vast expanses of empty space using invisible waves.

Today’s highly congested radio frequency spectrum stretches from waves of very low frequency (3,000 cycles per second) used for submarine communication to waves of super high frequency (30 billion cycles per second) used for satellite-based operations. This entire range is densely packed with traffic, and successful operation requires precise tuning at both ends so that distant receivers and transmitters can connect among the cacophony of many, many other signals. By contrast, at the dawn of the radio age, this spectrum was a desert that necessitated a broad, sloppy broadcast signal and imprecise tuning so that the first crude transmitters and receivers could find each other.

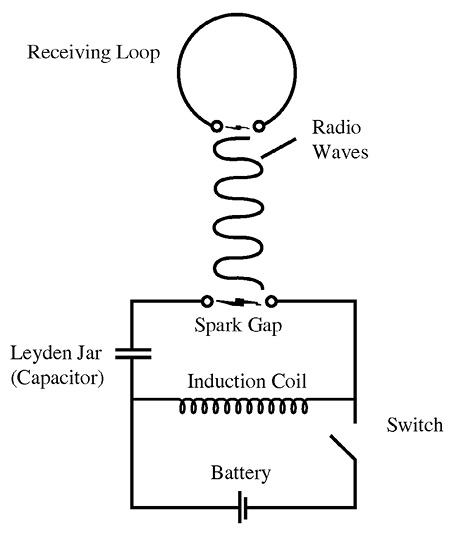

Figure 7-1. Schematic drawing of Hertz’ apparatus.

Like Hertz, Maxwell, and Faraday, Lodge was more interested in the scientific pursuit of pure knowledge than in commercial gain. In 1897, he filed the key patent that described the practical basis of tuning for the transmission and the reception of radio signals—known in those days by the more euphonious term “syntony”—but left to more aggressive souls its commercialization.7 Lodge knew that the lot of the technological entrepreneur, then as now, involved continual litigation, a fate he clearly did not desire:

The instinct of the scientific worker is to publish everything, to hope that any useful aspect of it may be as quickly as possible utilised, and to trust to the instinct of fair play that he shall not be the loser when the thing becomes commercially profitable. To grant him a monopoly is to grant him a more than doubtful boon; to grant him the privilege of fighting for his monopoly is to grant him a pernicious privilege, which will sap his energy, waste his time, and destroy the power of future production.8

Sometime around 1800, a Scotsman, Andrew Jameson, migrated to Dublin to engage in that most Scottish of industries, the manufacture of fine whiskey. He was following in the footsteps of his older brother John, whose brand of Irish whiskey survives to this day. Andrew’s business prospered, and he sired a daughter, Annie, who was endowed with a singing voice that reduced listeners to joyous tears. Covent Garden Opera House offered Annie an engagement that her father forbade her to accept on the grounds that it was not a proper venue for a respectable young woman. In consolation, he sent her on a grand tour of Italy.

Annie stayed with family business associates in Bologna, where she fell in love with Giuseppe Marconi, the widowed son-in-law of her hosts. He proposed, she accepted, but her father, outraged at her romance with an Italian widower seventeen years her senior, once more smothered her dreams and forbade the union. Brokenhearted, she returned to Ireland; passionate letters were smuggled in both directions, and when Annie came of age in 1864, she stole away across the Channel to France, where the two married. The couple returned to Bologna, where a year later they produced a son, Alfonso, and nine years after that, another, Guglielmo.9

Guglielmo had what we would today call a nontraditional upbringing. His parents put little academic pressure on the lad, who attended local schools only when the mood struck him, and by the time he reached college age he found himself unqualified to attend Bologna’s famous university. The story of how this superficially unimpressive young man surpassed his older and more illustrious competitors in radio communication, not only in England, but also on the Continent, in the United States, in Russia, and elsewhere evokes the unconventional paths followed by many of today’s high-tech pioneers.

From the first, Guglielmo took a shine to physics and chemistry; when the family summered in the Italian Alps in 1894, he carried with him a biography of Hertz. Astutely, he realized the communications potential of Hertz’s work on radio waves, and when he returned home he outfitted the vacant attic of the family mansion, Villa Griffone, for his experiments.10

Aside from a conveniently empty upper floor, the villa possessed another advantage: a neighbor, Augusto Righi, who was a giant in early electromagnetism research. Access to Righi’s library proved far more valuable than access to his laboratory, for the equipment used to generate and detect microwaves, Righi’s specialty, is very different from that for radio waves.

Grudgingly, Marconi’s tightfisted father financed his son’s early efforts, and this drove Guglielmo relentlessly toward commercial application, which in practice meant the propagation of radio waves over increasingly long distances. Whereas Hertz, Lodge, Righi, and their colleagues focused mainly on precise tuning, Marconi virtually ignored it. As he tinkered with his receivers and transmitters, he kept only those adjustments that increased transmission distance. After exhausting the range of the villa’s attic, Guglielmo expanded his experiments over the surrounding hills. Typically, he would transmit from the attic the letter “s”—three short dots that came across as three brief movements of the hammer on the receiver. At a distance of a few hundred meters, his brother Alfonso or a local tenant farmer named Mignani signaled with a kerchief the reception of the “s.” At one kilometer, Marconi could no longer see the kerchief, and so he instructed his assistants to fire a rifle shot instead when they received the signal; on a fateful day in 1895, he transmitted the “s” and almost immediately heard a shot that rang across the hills.11

While Hertz and Lodge had learned that radio transmissions generally travel over longer distances at longer wavelengths than at shorter wavelengths, Marconi had not. He may not even have been aware of a related key fact well known to Hertz and Lodge: that longer antennae resonated at longer wavelengths. All he knew was that the bigger he made his antennae, the more successful he was at transmitting over long distances. Marconi found that if he oriented the antennae of both transmitter and receiver vertically and buried their bottom ends in the ground, a technique abhorred by Lodge because it threw the tuning off, the signals could carry for miles across the Italian countryside. (When Marconi executed his first transatlantic transmission in 1901, his antennae at both ends extended from deep underground to high in the air on kites.)

In 1895, he offered his new technology to the Italian government, which politely refused it; his mother Annie’s British-Scottish family connections and England’s naval power made Britain the next likely customer. A year later, he traveled to Britain, accompanied by two formidable accessories: his radio frequency equipment, consisting of crude receiving and transmitting devices, not materially different from those designed by Lodge; and his mother. In remarkably short order, he garnered political and financial support from England’s technological and financial elite, including the post office’s chief engineer, William Preece, and the name Marconi became synonymous with early radio technology.

In 1897, the same year that Lodge acquired his patent, Her Majesty’s government also awarded one to Marconi for his devices. His machines utterly lacked tuning precision; they constituted, in the words of historian Hugh Aitken, “a practical system of wireless telegraphy only as long as there was very little wireless telegraphy.”12

The post office fully expected to operate England’s radio business, as it did the telegraph, but the government bureaucracy moved too slowly for Marconi; Preece’s support served merely to attract more nimble private capital. In July 1897 Marconi and his investors incorporated the Wireless Telegraph and Signal Company Ltd., which three years later changed its name to Marconi’s Wireless Telegraph Company. Many Britons felt that the company had unfairly capitalized on Preece’s endorsement of Marconi’s technology; this would stick in the government’s craw for decades thereafter.

Marconi continued his focus on pushing radio’s geographic range as far and as fast as possible. By 1897, he could throw his signals only a few miles. While the company’s spurning of the post office’s support evoked public anger, opprobrium never seemed to attach to Marconi personally, for both the public and the press lionized this inventor as the “wizard of wireless.” Marconi polished this image with a continuous stream of publicity-attracting stunts: connecting the coastal town of Bournemouth with the Isle of Wight in January 1898; connecting Bournemouth with London shortly thereafter; keeping Queen Victoria in touch with Prince Edward while he was recuperating from an appendectomy on the royal yacht when a storm blew down the telegraph lines; and last but not least, transmitting the single letter “s” across the Atlantic in December 1901.13 In the course of maximizing range, Marconi did make one major scientific discovery: the ionosphere, off of which he could bounce shortwave signals over great distances.

At the turn of the twentieth century, Marconi’s company very much resembled any modern Internet start-up with a whizbang product but no obvious source of revenue. For one thing, the new devices could transmit only brief bursts of signals, which could not encode the sound of the human voice, or anything else for that matter. Marconi certainly did not, as is commonly supposed, invent the modern radio. To the extent that he invented anything, it was the concept of marrying the telegraph key to the spark-generated signal; the only information he transmitted was the on-off of standard telegraph key Morse code.

To compound matters, Marconi’s first receivers were crude “coherers”: glass tubes with electrodes at either end and filled with metal filings that had to be reset through mechanical tapping after each message. Opportunistically, he soon pirated Lodge’s tuning circuits. In character, Lodge did not promptly sue. In 1911, Marconi settled the matter by buying Lodge’s unsuccessful company and, critically, its patents for transmitting and receiving antennae.

The major drawback of wireless telegraphy was far more prosaic: the telegraph already provided nearly instantaneous communication that, while far from cheap, was much more inexpensive, and reliable, than wireless communication. By the turn of the century, the global transoceanic submarine cable network had functioned well for a generation, and fourteen undersea cables spanned the Atlantic Ocean.

Early radio technology held a potential advantage in only one area: ship-to-shore and ship-to-ship telegraphy. Lloyd’s, the British marine insurance underwriters’ consortium, closely monitored shipping inbound on the “Western Approaches” off Ireland’s southern tip. Because of fog, the ships often could not be sighted from shore, but generally could be seen from Rathlin Island, which lay a few miles south of the Irish mainland and which could be reached more cheaply by wireless signals than with a submarine cable. Alas, Marconi’s company received no contracts for a few years after filing the 1897 patents; even when he successfully passed a signal across the English Channel in 1899, it attracted no business.

Given the uncertain financial prospects of Marconi’s venture, private incorporation served it well; the company was largely controlled by Marconi and his family, who did not clamor, as public shareholders or government sponsors are wont to do, for immediate dividends. The capital structure of the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company allowed it to plow all of its revenues back into the business for longer-term gain. Soon, the family’s patience paid off; the Admiralty signed on in 1900, followed by Lloyd’s in 1901.

So attractive was marine telegraphy to Lloyd’s that it agreed to lease, not buy, Marconi’s equipment, which Lloyd’s employees then operated. (Marconi forbade Lloyd’s employees from communicating with stations and ships not equipped by him.) In an early demonstration of “network externality,” in which the value of a service grows exponentially with the number of users, the company’s business boomed; by 1907 it served virtually all of the world’s ocean liners. This effective monopoly, which the company’s contracts specified would last until 1915, produced a backlash in the form of the 1907 International Convention on Wireless Communication at Sea, which prematurely broke the company’s stranglehold the next year, seven years in advance of the 1915 contract date.14

Marconi’s seemingly magical transmissions of messages over ever-longer gaps of empty space electrified the public imagination, but this did not impact the life of the average citizen, who was not likely to employ Marconi’s specialized services, let alone purchase an extremely expensive radio transmitter or receiver. Until 1906, no one had figured out how to encode sounds into radio waves, as Alexander Graham Bell had done in 1876 with the telephone. Not until after World War I did reliable and inexpensive vacuum tubes for transmitting and receiving sounds via radio waves become available.

While radio emerged to play a substantial role in military communications on both sides in World War I, at that time it carried little political or cultural freight. As so often happens with exciting new technologies with as yet uncertain application, self-promoters and con men stepped into the breach. In the first category was Lee de Forest, a talented, single-minded, but egomaniacal inventor. He had studied under the great physicist J. Willard Gibbs at Yale and earned a PhD in electrical engineering in 1899. De Forest’s innovative ability sprang from the happy combination of lab bench skill and a habit—inculcated at Yale—of assiduous surveillance of the scientific literature. For both better and worse, he associated with Abraham White, a Texas-born fraudster whom de Forest tapped for start-up capital.

In 1902, White incorporated the De Forest Wireless Telegraph Company in New Jersey with $1 million of investors’ seed money, soon followed by nearly $20 million in ever-larger stock offerings under different names.15 White feted “investors” at elaborate Potemkin village “executive offices” and “research facilities,” and his impressive “radio towers” were constructed at locations convenient for sales, but not for aerial transmission. When de Forest lost a patent suit in 1906, White froze him out by transferring all the assets of the largest of the companies, American De Forest Wireless Telegraph, to White’s own wireless company, United Wireless Technology, whose revenues consisted almost entirely of bogus stock flotations. Four years later, postal inspectors closed it down.16 It would not be the last time that de Forest’s poor judgment of character undid his efforts.

De Forest also had the bad habit of appropriating the inventions of others. His attention to scientific journals provided him with a steady stream of new potential devices, the most notable of which was the Fleming valve, the precursor to the vacuum tube. In 1883, John Ambrose Fleming, while working for Thomas Edison, took an interest in a particular variation in one of his boss’s incandescent bulbs; it had the interesting characteristic of transmitting an electrical current across its vacuum—something that seemed impossible. The current, it turned out, consisted of electrons, whose existence would eventually be proved by physicist J. J. Thomson, but not for more than another decade: without realizing it, Edison and Fleming had invented a device that would, with subsequent modification, allow radio waves to transmit sounds, including the human voice.

Edison, a profoundly practical, untheoretically-minded man, inexplicably missed its potential. Instead, he directed Fleming’s attention to more commercial applications, but Fleming did not forget the unusual behavior of their curious bulb. When Fleming came into the employ of the Marconi Company, he investigated its use in the reception of radio waves and found it highly promising. Once more, Fleming’s superiors ordered him to work on other projects. Fleming then compounded both of his bosses’ initial misjudgments by making an innocent but fatal mistake of his own: he published his results in a highly respected academic journal, Proceedings of the Royal Society.

Just a few months after the article appeared, an assistant of de Forest brought a bulb to the New York factory of Henry McCandless, a manufacturer of automobile lights, with instructions to duplicate it. The bulb, the assistant unthinkingly informed McCandless, was a Fleming valve. Several weeks after that, de Forest took out a patent on it, conveniently relabeling it a “static valve for wireless telegraph systems,” and he followed this piracy several weeks afterward with a similar patent that gave the valve a catchier name reflecting its ability to decode broadcast sounds: the “audion.”

The audion was not altogether a theft: de Forest modified and improved Edison and Fleming’s original design by adding a third wire between the filament and the plate. Even so, one of McCandless’s assistants made the critical suggestion: the bending of the third wire into a zigzag shape, thereafter called the “grid.” Because he had “borrowed” a large part of its design, de Forest did not understand how the audion worked, and he later demonstrated his confusion all too clearly on the witness stand in patent infringement suits.

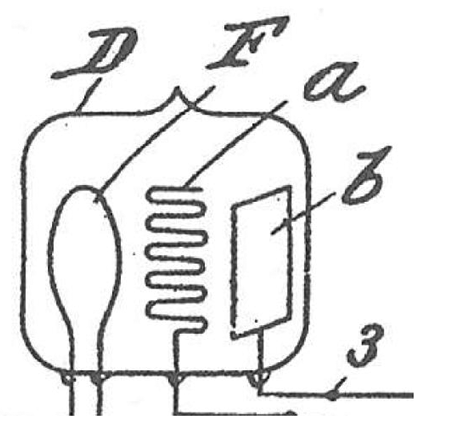

Figure 7-2. Detail from de Forest’s 1907 patent application for the audion. [F] represents the filament and [b] the plate, whose basic design he “borrowed” from a scientific publication by John Fleming, an employee of Thomas Edison. The “grid” [a] between the two was probably de Forest’s idea; an assistant of his bulb manufacturer, Henry McCandless, suggested bending the grid into its zig-zag shape.

The audion, as noted above, gave rise to the vacuum tube, which may well have been one of modern man’s most important inventions. The vacuum tube made possible the almost infinite amplification and regulation of electrical currents: a small lever linked through a vacuum tube could vary the output of a thousand-horsepower motor. Even more critically, the tubes could effect this amplification instantaneously and thus completely eliminate the need for human intervention; instead of moving a lever, the tube could respond to tiny changes in force, temperature, speed, frequency, brightness, or any other measurement that could be transmuted into an electrical current. These completely automatic processes were first fully realized in the Manhattan Project and with the radar control of antiaircraft fire in World War II, then became nearly ubiquitous in factory processes, and finally spread to automobiles and household appliances.

By World War I, technological innovation had ceased being the product of lone geniuses; it had shifted to corporations large enough to undertake ever more expensive research. The names involved, while well-remembered among engineering historians—Reginald Fessenden, Charles Steinmetz, and Edwin Armstrong, among others—do not resonate historically like those of Edison, Bell, and Marconi. This new generation of radio entrepreneurs would have done well to heed Lodge’s warning, for litigation took its toll on most of them. Armstrong, who invented FM broadcasting and the superheterodyne receiver used in nearly all modern televisions and radios, was perhaps the greatest radio engineer who ever lived. Ultimately, he jumped to his death in despair over unfavorable patent rulings and abuse at the hands of RCA, the successor to the Marconi Company. The opportunist de Forest, by comparison, got off lucky: he merely died broke.17

Nonetheless, during the early twentieth century, these less well-known innovators dramatically improved the amplification ability of vacuum tubes to the point that they could easily pull in weak signals from distant continents. At the same time, the new tubes also enabled high-frequency transmitters capable of encoding the human voice and music.

On Christmas Eve 1906, Reginald Fessenden broadcast from a transmitter in Brant Rock, Massachusetts, Handel’s aria “Ombra maifu,” followed by his own violin solo and Bible reading; the words and music could be heard hundreds of miles away.18 Even so, this first public voice broadcast thrilled only radio enthusiasts and hobbyists, whose heads were squeezed by earphones tight enough to cut off the blood flow and whose backs were hunched over temperamental homemade mineral and cat’s whisker receivers. The equipment at both ends—particularly the receivers—was still far too expensive and unreliable for general use.

Another ingredient necessary for the popular adoption of radio was lacking as well: commercial vision. As obvious as its mass-market communication potential is today, in the years surrounding World War I it took a special kind of imagination to conceive of radio as a consumer enterprise, let alone to envision the form it would eventually take. None of the inventions discussed in this book, from writing onward, were designed with mass communication in mind; their development hinged for the most part on limited commercial, governmental, and military uses, and in some cases on intellectual and technological curiosity alone; Gutenberg, after all, printed only 180 Bibles, and the creators of the telegraph had mainly railroad and financial applications in mind.

Nowhere was this truer than with radio. Faraday and Hertz conceived no commercial designs at all, and Lodge’s came mainly as an afterthought. Even the visionary Marconi focused almost entirely on shipping companies, insurers, and navies. As late as the beginning of World War I, no one imagined the average consumer using a radio receiver for any purpose. That transformation would fall to one of the most singular characters in American business history, David Sarnoff.

Born in 1891, Sarnoff hailed from the desperate poverty of the tiny Jewish shtetl of Uzlian in western Russia; when he was five, his father, Abraham, already ill from tuberculosis, emigrated alone to New York City. The rest of the family joined him four years later, and during that interim David was consigned to the care of a rabbinical granduncle, the head of his mother’s deeply scholarly and religious extended family.

Each day, young David had to memorize two thousand words of biblical Hebrew or Talmudic Aramaic; failure meant going to bed hungry. This left him with both a singular power of concentration and a burning desire to avoid any further religious study.

From nearly the moment he stepped onto American soil at age nine, David served as head of the family; within a few years he had built a string of newspaper stands that employed his brothers. When he turned fifteen, his father became bedridden, and so he went looking for a higher-paying job.

By that point, David had benefited not only from New York’s educational system, but also from the Educational Alliance, a secular East Side organization that served the immigrant community and taught him to write and debate in fluent English. Inspired by the city’s burgeoning penny newspaper industry, he imagined himself the next William Randolph Hearst or the next James Gordon Bennett of the New York Herald. In September 1906, he strode confidently into what he thought was the lobby of Bennett’s newspaper in Herald Square and announced to the lobby clerk that he wanted to work for the paper. The attendant replied, “You’re in the wrong place. This is the Commercial Cable Company, not the Herald. But we’re looking for a messenger boy. Can you handle it?”19

Soon enough, like the young Thomas Edison, David became fearsomely competent at Morse code. Several months later, just before his father died, Commercial Cable refused to allow him time off for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur; he protested and was fired. The hand of fate next sent him to the Marconi Company.

On such serendipity does history pivot. At Marconi he, more than any other human being before or since, shaped how the world saw and heard itself, and so determined the fates of nations. Sarnoff spent the next decade at Marconi rising through the ranks. The company assigned him to venues as varied as arctic seal-hunting expeditions and Marconi’s station atop New York’s Wanamaker Building, where he handled the sparse radio traffic between the Philadelphia and New York stores. The glassed-in facility was, in fact, a publicity stunt cooked up by the Marconi and Wanamaker companies; Sarnoff’s job there was to expound the magic of radio to visitors.

This agreeable public relations gig abruptly turned deadly serious on the night of April 14–15, 1912, when the Titanic sank, and the Wanamaker office swarmed with frantic relatives awaiting survivors’ names from the rescue ship Carpathia. Ironically, the White Star Line had offered the famous Marconi free passage on the ship, but he declined. He traveled instead on the Lusitania, whose stenographer he preferred.20 (Three years after an iceberg sank the Titanic, a German submarine would sink the Lusitania.)

The U.S. Senate later grilled Marconi over the slow release of information that evening by Sarnoff and others, but, as usual, Marconi came up smelling like a rose, the genius whose invention “saved” hundreds of lives.

The next year Sarnoff, by now the company’s chief inspector, and three other Marconi engineers visited the radio laboratories of Columbia University, where Edwin Armstrong showed them a prototype of his remarkably sensitive vacuum-tube receiver, and in the coming months, Sarnoff and his colleagues convinced themselves of its commercial usefulness. Marconi himself, who by this time had returned to England, also investigated Armstrong’s receivers, but he was not as impressed. Mass communication was just too much of a stretch even for the company’s visionary founder; after all, his wireless telegraph company transmitted messages between individuals, where secrecy was usually of the highest concern. Only Sarnoff realized that the ease of intercepting radio signals, far from being a drawback, could be exploited to great benefit. In 1915, he sent his famous “radio music box memo” to his immediate supervisor, Edward Nally:

I have in mind a plan of development which would make radio a “household utility” in the same sense as the piano or phonograph. The idea is to bring music into the house by wireless.

While this has been tried in the past by wires, it has been a failure because wires do not lend themselves to this scheme. With radio, however, it would seem to be entirely feasible. For example—a radio telephone transmitter having a range of say 25 to 50 miles can be installed at a fixed point where instrumental or vocal music or both are produced. The problem of transmitting music has already been solved in principle and therefore all the receivers attuned to the transmitting wave length should be capable of receiving such music. The receiver can be designed in the form of a simple “Radio Music Box” and arranged for several different wave lengths, which should be changeable with the throwing of a single switch or pressing of a single button.21

Sarnoff’s vision would not come easily, for in 1915, neither the American Marconi Company nor any other commercial operation possessed the wherewithal to erect the broadcasting network and build the millions of radios to receive its signals. During World War I, the U.S. Navy, which coveted Marconi’s huge transmitters, had taken over not only all radio production, but the patents themselves. At war’s end, the Marconi Company wanted to purchase the most advanced GE alternator-driven transmitters, but both the navy and Congress argued that it should be prohibited from doing so, since it was incorporated in Britain. In addition, when the war ended, the navy had no desire to relinquish the turf it had acquired: in December 1918, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels testified before Congress, “It is my profound conviction, as is the conviction of every person I have talked with in this country and abroad who has studied the question, that [radio] must be a monopoly.”22 Daniels did not need to mention who the monopoly holder would be. (In the 1920s, the cohabitation of the American radio frequency spectrum by both the navy and hobbyists resulted in a series of spectacular, and far from harmless, practical jokes as pranksters posing as admirals sent cruisers and battleships scurrying across the seven seas on bogus missions.)23

But by the end of the war, the American public was heartily sick of government control of anything, so a compromise was reached: the divisions of General Electric that manufactured the high-powered transmitters would merge with the Marconi Company to form a new entity, Radio Corporation of America (RCA), which was incorporated on October 17, 1919. As a sop to the navy, its chief of communications, Rear Admiral William Bullard, received a seat on the new RCA board. Additionally, the government granted RCA and AT&T monopoly status for the manufacture of the critical superheterodyne radio tubes and for telephone transmission, respectively.24 In 1926, RCA would cooperate with GE, Westinghouse, AT&T, and United Fruit to form the National Broadcasting Company (NBC).

Soon after, in 1920, the nation’s first commercial radio stations began operations—KDKA in Pittsburgh, WWJ in Detroit—and the price of reliable, commercially produced radio sets slowly fell. Just as David Sarnoff had predicted, the radio became the ornate mahogany god of the American living room: there were three million sets in 1924, thirty million in 1936, and fifty million by 1940, by which time a simple radio could be had for less than ten dollars. Network externality, chicken-and-egg yet once more: the increasing number of sets fed the demand for more stations, which grew to 275 in 1935 and then 882 in 1941; more stations begat yet more demand for radio sets.

In our current information-soaked age, it is difficult to imagine the thrill of bringing Jack Benny, Fred Allen, and Bob Hope into the living room for the first time, let alone a onetime event like the Joe Louis–Max Schmeling boxing match. By the mid-1930s, the average American spent more hours listening to the radio than reading newspapers or attending movie theaters, concerts, and plays combined; social workers reported that families did without beds and iceboxes to purchase a radio set.

The above sales figures understate radio’s penetration, since programs were not just a family event; they often involved neighbors as well. By 1935, only a few of the 127 million Americans could not at least cadge an invitation to listen from a neighbor, friend, or family member.25

Just as Martin Luther intuitively grasped, at a time when few of his ecclesiastical opponents did, the persuasive power of the printing press, so too did Franklin Roosevelt appreciate, at a time when few of his ideological opponents did, the persuasive power of radio. He understood, well before any other American politician, Archibald MacLeish’s injunction in this chapter’s epigraph about the gullibility of the ear.

At the time of the 1932 election, Roosevelt had a communications problem: his ideological opponents largely controlled the nation’s newspapers. Although nominally a Democrat, Hearst opposed nearly all of Roosevelt’s policies; an even more serious threat to the New Deal was the archconservative publisher of the Chicago Tribune, Robert McCormick. Not only did radio offer Roosevelt wide-open access, but in that innocent age, the president of the United States could draw an audience share on a par with Benny, Hope, Louis-Schmeling, or a New York Yankees game.26

In proficient hands, radio possesses enormous emotive power, in no small part because, especially during its first decades, it was usually experienced in a social environment. The first two presidents to broadcast, alas, did not emote. Calvin Coolidge’s nasal voice put off audiences. Herbert Hoover, in contrast, seemingly possessed a huge advantage with the new medium, since his engineering background gave him a special interest in the field. As Coolidge’s secretary of commerce, he devised a system for awarding frequencies, chaired the 1927 International Radio Conference, wrote treaties governing global radio traffic, and played a key role in the establishment of the Federal Radio Commission, the forerunner of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). Regrettably, Hoover’s emotionless delivery put listeners to sleep; even more seriously, he did not know when to stop talking. During the 1932 election campaign, he gave an address that was to last exactly one hour and end just before the start of the enormously popular Ed Wynn vaudeville show. His speech was a disaster. According to an account in The Nation:

Even Americans will rebel if things go too far. At eight-thirty on a recent evening, the populace of the United States, respectful if dubious, tuned in on Mr. Hoover’s portentous speech in Iowa. At nine-thirty, accustomed to the prompt intervention of the omnipotent announcer, the listeners confidently awaited the President’s concluding words. . . . But Mr. Hoover had only arrived at point number two of his twelve-point program. The populace shifted in its myriad seats; wives looked at husbands; children, allowed to remain up till ten on Tuesdays, looked with alarm at the clock; twenty thousand votes shifted to Franklin Roosevelt. Nine-forty-five: Mr. Hoover had arrived at point four; five million Americans consulted their radio programs and discovered that Ed Wynn’s time had not been altered or canceled; two million switched off their instruments and sent their children to bed weeping; votes lost to Mr. Hoover multiplied too fast for computation. . . . What did N.B.C. mean by this outrage? Whose hour was it anyhow? Ten million husbands and wives retired to bed in a mood of bitter rebellion; no votes left for Hoover.27

By contrast, Roosevelt’s voice, demeanor, and temperament were made for radio. He had no need to command Hoover’s knowledge of the technology, for he possessed a unique insight into the medium’s political potential. Most normal conversation occurs at a rate of about 300 words per minute (wpm). Throughout history, experienced orators had slowed that down to about 150 wpm, as did most radio announcers. Roosevelt rarely exceeded 130 wpm, and the more important the speech, the more slowly he talked; his address at the outbreak of World War II in September 1939 was clocked at 98 wpm; and his speech after Pearl Harbor at 88 wpm. To today’s ear his voice sounds aloof and aristocratic, as do most radio announcers and movie actors from the period, but in the 1930s, Roosevelt’s intonation struck listeners as down-to-earth, even slightly folksy. Radio engineers loved him; so even were his timbre and modulation that they rarely needed to touch their dials.

Roosevelt carefully crafted his delivery; although he benefited from the best verbal stylists in his famous “brain trust,” he wrote the texts himself and then spent hours polishing them. He possessed as wide a vocabulary as any Harvard graduate, but consciously restricted his content to the most commonly used English words. His favorite slot was Sunday at ten PM, when the public was “relaxed and in a benevolent mood.”

The Princeton University psychologist Hadley Cantril recognized that radio had caused an earthquake in the public mind-set, and that those who understood it, such as Roosevelt, could wield enormous power. In the early 1930s, he observed a unique “natural experiment” in public speaking in Boston, where a popular evangelist gave an address. The hall the evangelist had rented could not accommodate all who came, and the overflow audience members were directed to a nearly identical hall on the floor below, where they listened to the preacher on a loudspeaker.

The in-person audience upstairs rocked the hall with tears, shouting, and laughter and filled the preacher’s coffers, while the people listening to the loudspeaker in the lower hall fidgeted and left only a few copper coins. Cantril realized that the dynamics of the personal performance in the upper hall varied greatly from the more radio-like performance downstairs. In short, radio had turned the age-old art of oratory nearly on its head, for like the preacher’s lower hall, it utterly lacked visual cues. While this is a disadvantage to the personally attractive and physically dynamic speaker, it greatly helps one who has a calm, soothing voice and who can keep a speech short; if, while speaking, he shuffles papers or fiddles, no one is any the wiser.28 For every Roosevelt who profited from the new style, there was a Herbert Hoover who did not.29

Cantril noticed that the president’s radio addresses rarely exceeded twenty minutes; although a particularly compelling speaker can command an audience’s attention for up to a few hours, the attention span greatly shortens when a disembodied voice emanates from a loudspeaker without visual cues.30 The psychologist was amazed by the ability of Huey Long, the populist governor of Louisiana and United States senator, to enlist thousands of his radio listeners as his coconspirators, having them call their friends and neighbors about his broadcasts, and by the way the anti-Semitic Catholic priest Charles Coughlin bowled over his audiences with ridiculously simplistic solutions to complex problems. Cantril drily remarked, “A sound argument is always less important for the demagogue than are weighted words.”31

Roosevelt also intuitively understood how to take advantage of radio’s highly centralized structure. Through the newly established FCC, he led a campaign to strictly separate newspaper and broadcast station ownership. While this no doubt served the public interest by diffusing control of the media, it served Roosevelt even better, for it excluded the likes of his political foes, McCormick and Hearst, from the airwaves—the latter having already begun to use his wealth to accumulate a radio empire.

Roosevelt, in addition, made a tacit deal with the leaders of the nascent broadcast industry, who must have cast a nervous eye on state ownership of radio across the Atlantic and on the emergency economic conditions at home: I’ll keep my hands off your stations as long as you provide me with access and deny it to my opponents. The president generously allowed radio reporters into press conferences, and in exchange the networks gave Roosevelt instantaneous, on-demand entrée to the airwaves. The president especially cultivated popular commentators such as the brilliant Dorothy Thompson and the nasty, bitter Walter Winchell. In exchange for scoops, Roosevelt expected, and received, favorable coverage for himself and for his policies.

Finally, radio offered Roosevelt yet one more advantage: as a purely verbal medium, it hid his physical disability. As an inaugural gift, in 1933 NBC gave the president a microphone stand with special handlebars and leg brace fittings.

Almost from the moment he took office on March 4, 1933, Roosevelt commanded the airwaves. On March 9, with the nation in the midst of a horrifying banking crisis, the president declared a bank holiday; three days after that, he took to the microphone with a stirring address that calmed the nation and largely restored faith in the financial system.32 Will Rogers opined that Roosevelt explained the machinery of banking so well “that even bankers understood it.”33

Over the twelve years of his presidency, as radio completed its penetration of American society, Roosevelt honed his technique. By 1941, a typical fireside chat probably reached nearly three-quarters of the American public. An entire generation fell under the spell of Roosevelt’s radio mystique, including the young Jimmy Carter. As described by Carter’s biographer, James Wooten:

The resonant tones of the President of the United States slicing crisply through the static from faraway Washington, would remain and endure for [the young Carter] as an oral symbol of authority and strength, leadership, and hope, a force in his life that he would never quite escape or outgrow.34

On only one occasion did Roosevelt’s radio magic fail him: his ominous attempt to pack the Supreme Court. Frustrated by its obstruction of key New Deal legislation, he proposed the appointment of one extra associate justice for each serving justice over the age of seventy who had sat for more than a decade.

The effort failed, but just barely. Polling data showed a bump in public support for the packing bill with each fireside chat on the topic; after his major address on the subject on March 9, 1937, 48 percent considered the proposal favorably, probably enough for passage.

Roosevelt failed to follow up his accumulating success with more broadcasts, and over the ensuing weeks the polling data deteriorated. The public also noticed that Charles Evans Hughes, who was now chief justice—a well-loved and respected figure—did not conform to Roosevelt’s caricature of senior justices as decrepit old men. (Although Hughes worked behind the scenes to defeat the Supreme Court bill, he had previously polished his credibility regarding the issue by ruling most of the New Deal legislation to be constitutional.) By 1937, the political opposition had finally learned to use the airwaves, especially senators Burton Wheeler, Kenneth Burke, and Royal Copeland, who gave stirring radio addresses in opposition to packing the court. In particular, Burke’s speech caught the public imagination by turning around Roosevelt’s famous catchphrase to assert that if the president succeeded, “Constitutional democracy was facing a rendezvous with death.”35 In spite of Roosevelt’s failure to alter the court through legislation, he succeeded through sheer longevity by appointing eight justices during his twelve years in office.

This one failure aside, it may not be an understatement to attribute Roosevelt’s unprecedented four electoral victories largely to his command of the medium, nor an exaggeration to describe that command as hypnotic.36 Unfortunately for Jimmy Carter, though he was smitten with Roosevelt’s radio magic, none of it rubbed off on him. Ronald Reagan, who began his career as a radio sports announcer during the Roosevelt era, probably did learn from the master and used his talent to defeat Carter in the 1980 presidential election.

Franklin Roosevelt, the young Jimmy Carter, and Ronald Reagan were not the only Americans to understand the manipulative potential of radio. In 1938, Orson Welles, the enfant terrible of the American stage, inadvertently demonstrated the awesome power of the new medium not just to distort reality, but to invent its own.

Welles wasn’t consciously trying to make trouble. H. G. Wells’ War of the Worlds, a late-nineteenth-century short novel about an alien invasion, seemed like a good story for his Mercury Theater Radio to read on its regularly scheduled Sunday evening broadcast just before Halloween. The problem was that, as was his wont, Welles had modernized the script. In this case the revisions were done by a talented screenwriter, Howard Koch, who moved the novel’s action from London to Grover’s Mill, New Jersey, halfway between New York City and Philadelphia. Koch then happily set about destroying much of the northeastern United States.37 Welles’ collaborator, actor John Houseman (whose signature role was his screen and television portrayal of an intimidating Harvard Law contracts professor in Paper Chase) worried that the production of the musty Victorian novel would put audiences to sleep.

It did not. The very first words out of the announcer’s mouth clearly informed listeners that the Mercury Theater was presenting the H. G. Wells novel, and this remark was followed by a few minutes of fictional historical prologue not likely to scare anyone. The broadcast then segued to the sound of an imaginary orchestral program suddenly punctuated with, “Ladies and gentlemen, we interrupt this program of dance music to bring you a special bulletin from the Intercontinental Radio News.”

There then followed some descriptions of mysterious explosions on Mars, and the arrival of shiny metal cylinders in Grover’s Mill, all interspersed in the program of dance music. A few minutes later hideous slimy creatures arose from the cylinders and mounted huge traveling machines that fired death rays, emitted poison gas, and, in short order, defeated the army and its air arm, occupied New York City, and destroyed most human life in their general vicinity.

Welles’ technique of dressing up old scripts in contemporary clothes amplified the credibility of his productions. When he staged Macbeth, he decked out his actors in 1930s fascist garb. In the War of the Worlds broadcast, the ill-fated New Jersey militia commander sounded suspiciously like General Douglas MacArthur; the smooth-talking secretary of the interior’s delivery was nearly identical to FDR’s; and the announcer’s general tenor was modeled on the radio reportage of the earlier, all too real Hindenburg disaster and of the Munich crisis. All these factors contributed to the broadcast’s terrifying impact.

During the Sunday night broadcast, tens of thousands of Americans fled their homes and crowded onto highways in a panic, flooded police stations with concerned phone calls, donned their World War I gas masks recovered from the attic, and even had hallucinations: some saw New York City burning on the horizon; not a few claimed to have seen the Martian fighting machines and flying cylinders.

Not more than ten minutes into the performance, it was apparent to nearly all stations broadcasting the program that there was trouble; most interrupted it with extra statements about its fictional nature; William Paley, the president of CBS, materialized at the Mercury Theater studio in his robe and slippers to investigate.

Welles also soon became aware of the sensation he was creating, but refused to break the story’s flow with an extra announcement, telling one executive, “What do you mean interrupt? They’re scared? Good, they’re supposed to be scared. Now let me finish!”38 Later, he unashamedly defended this refusal as a warning about the gullibility of the public to radio broadcasts.

A few years later, Professor Cantril produced an authoritative analysis of the event. He found that those audience members who mistook the broadcast for reality tended to have missed most of it, particularly the beginning, and to have lower socioeconomic status and educational levels; southerners were more easily fooled than northerners. Curiously, those who listened with friends were far more likely not to check the veracity of the story by tuning in other stations to discover that nothing was actually going on; Cantril interpreted this as the result of social reticence.39

In many respects, War of the Worlds constituted a perfect media storm: a brilliantly executed knockoff of a contemporary news broadcast–cum–fireside chat delivered during a time of high anxiety over national security. The inherently persuasive nature of radio as a stand-alone one-way medium controlled by a very few network officials heightened the effect; it is difficult to imagine television being able to assemble a package of both verbal and visual information into such a convincing hoax, particularly in the modern cable and Internet environment of thousands of simultaneously available outlets.

The broadcast would have done more damage but for the fact that it ran opposite the far more popular Charlie McCarthy show, named after its star, ventriloquist Edgar Bergen’s wooden sidekick. One literary critic reached a conclusion different from Cantril’s, writing to Welles: “This only goes to prove that the intelligent people were listening to a dummy, and all the dummies were listening to you.”40

Cantril’s analysis of the event brilliantly fingered the source of radio’s hypnotic power:

By its very nature radio is the medium par excellence for informing all segments of a population of current happenings, for arousing in them a common sense of fear or joy and for enticing them to similar reactions toward a single objective. . . . The radio audience consists essentially of thousands of small, congregant groups united in time and experiencing a common stimulus—altogether making possible the largest grouping of people ever known.41

Human beings are profoundly social creatures and constantly feed off the emotions of those around them; the larger the group, the more intense the experience, as anyone who has ever attended a professional sporting event, a mass political rally, or even a moving lecture can attest. A key factor in all these settings is the simultaneity of the event; while radio does not assemble human beings in person, it made it possible, for the first time, to assemble millions of them in time, as Franklin Roosevelt had already discovered to his advantage.

Casting his eyes to the future and across the Atlantic, Cantril also worried that:

The day cannot be far off when men in every country of the globe will be able to listen at one time to the persuasions or commands of some wizard seated in a central palace of broadcasting, possessed of a power more fantastic than Aladdin.42

His concern proved horrifyingly prophetic, for in those parts of the world lacking the institutional checks and balances of the United States Constitution, radio would amplify the potential of the world’s totalitarian governments right up until the end of the twentieth century.

Paul Joseph Goebbels was born in 1897 to a poor, devout German Catholic family. The Catholic Church early on recognized his intellectual talent, and, having been rejected for military service because of his clubfoot, he was able to earn a doctorate in literature from Heidelberg University in 1921. His brilliance, physical deformity, short stature, and dusky complexion—hardly an advertisement for the Nazi Teutonic ideal—combined to produce a bitter, sarcastic personality and a genius for manipulating the minds of men. Nazi press chief Max Amann called him “Mephistopheles.”43 Hitler recognized his unique talent early, and in 1926 appointed him the Berlin party leader.

Berlin became Goebbels’ propaganda laboratory. In the 1920s, in the aftermath of the Beer Hall Putsch, the Nazi Party was little more than a ragtag group, and he was forced to attract attention any way he could, most commonly by starting public brawls with communists and socialists. In Berlin, Goebbels also found his voice as an orator and learned to sway the masses he so despised.

Gradually, he learned that the voice convinced far better than the pen. Analytical to a fault, he studied history’s great persuaders: Christ, Buddha, Zarathustra, Robespierre, Danton, Mussolini, and, of course, Lenin:

Has Mussolini been a scribbler, or a great orator? Did Lenin, when arriving in St. Petersburg from Zürich, go from the railway to study and write a book, or did he instead address thousands of people?44

What better way to preach to thousands, or even millions, of people than radio? Even before the Nazis assumed power in January 1933, the Weimar government had put all radio stations under the control of a loose group of semipublic national and regional committees. In March 1933, Hitler appointed Goebbels head of the new Propaganda Ministry; five months later the new minister declared, “What the press was to the nineteenth century, radio will be to the twentieth.”45

By the time the Nazis took power, Germany already had excellent radio coverage, but the receivers cost far too much for the average citizen. Goebbels remedied this with the Volksempfänger, or “people’s set,” which had weak long-wave and medium-wave reception and no shortwave band at all, and thus could not easily bring in foreign broadcasts. Its initial version sold for seventy-six marks—about twenty dollars, half the cost of the cheapest previous models. Subsequent variations sold for half again less.46

Little was left to chance. The Propaganda Ministry’s broadcast office organized a network of “wireless wardens,” tasked with directing the people’s attention to the radio; arranging loudspeaker-equipped public listening areas; and, at the workplace, preventing anyone from leaving his or her desk while the Führer or Goebbels was speaking.47 The government required that all radio dials display little red placards, which proclaimed, “Racial Comrades! You are Germans! It is your duty to not listen to foreign stations. Those who do so will be mercilessly punished.” As indeed Germans were; merely listening could earn years of hard labor. Radio miscreants did not even have to be caught in the act—the discovery during a house search of a dial left tuned to a foreign station was enough to ruin one’s life.48 The Nazis dealt far more severely with those who repeated foreign broadcasts:

The Nuremberg Special Court [not to be confused with the famous postwar trials of Nazi leaders] has sentenced the traitor Johann Wild of Nuremberg to death for two serious radio crimes. . . . He behaved as an enemy of the state and people by continuously listening to hostile broadcasts from abroad. Not content with that, he composed insulting tirades whose source was the enemy station. In these tirades he revealed his treachery to the people by vulgar abuse of the Leader.

Wild’s punishment was far from rare; BBC editors were fond of scribbling on substandard copy, “Would you risk your life to listen to this?”49

In the 1930s, César Saerchinger was a member of the legendary CBS news team—the “Murrow Boys.” Just before Edward R. Murrow replaced Saerchinger as the network’s chief European correspondent, Saerchinger wrote a compelling description of the well-oiled Nazi radio machine in Foreign Affairs:

In their hands the radio has become the most powerful political weapon the world has ever seen. Used with superlative showmanship, with complete intolerance of opposition, with ruthless disregard for truth, and inspired by a fervent belief that every act and thought must be made subservient to the national purpose, it suffuses all forms of political, social, cultural, and educational activity in the land.50

In 1937, Saerchinger reported on the Berlin May Day celebration. For several hours before its high point—Hitler’s speech—the airwaves were filled with a hysterical narration of the arrival of each marching contingent, accompanied by thunderous cheering and martial music. As Hitler’s car made its way through the city, it was followed by a truck from which an announcer broadcast the Führer’s progress. As he left the vehicle and approached the platform, all Germany could hear the crowd rise to fever pitch, shouting Der Mai ist gekommen, Heil Hitler!

In contrast to Roosevelt, whose rhetoric ran to soft, measured cadences designed to convey calm, Hitler’s shrieks expressed his country’s anger at the “stab in the back,” the idea that since in the final weeks of the war, Germany appeared to be winning, its defeat must have been due to a domestic fifth column—the communists and the Jews. His speeches were almost rhythmically punctuated by the crowd’s cheering, whose broadcast volume radio technicians carefully modulated. Saerchinger remarked that neither Hitler nor Mussolini ever spoke before a microphone in a quiet studio or office, as did the American president.

When Hitler spoke, everyone, German or foreigner, stopped and listened, whether he wanted to or not. Again, Saerchinger:

Needless to say, there is no dissent; the use of radio, as of all vocal expression, is reserved exclusively for those who serve and incidentally own the state.51

Goebbels and Hitler could be subtle when subtlety suited their purposes. Just as they allowed the newspaper Frankfurter Zeitung, as an important international face of the regime, relatively free editorial rein, so, too, did they not censor the radio and press reporting of foreign correspondents in Germany, in marked contrast to the British, who did. This did not go unnoticed by American reporters, who found that it was easier to get the facts in Berlin than in London. In a similar vein, during the 1936 Olympics (which had been awarded by the Olympic Committee long before the Nazis came to power), the rabid anti-Semitism of the press and radio was toned down.52

Saerchinger closed his piece by describing how the Nazis strove to keep the populace from listening to the powerful French station in Strasbourg, not only by making the receiving of foreign broadcasts illegal but also by jamming. He ended his essay on this somber note: “Only an incorrigible optimist would deny that in the last analysis this feverish building of radio facilities is part of the general preparation for war.”53

Goebbels and Hitler understood radio’s immense centralized power at least as well as Roosevelt, and they exploited it to far more nefarious, and ultimately cataclysmic, ends. A half century later and a continent away, history tragically repeated itself.

After 1960, multiple factors mitigated radio’s totalitarian potential: the decreasing costs and increasing accessibility of telephone, fax, and personal printing and copying devices; the miniaturization of cheap long-range radio receivers capable of pulling in foreign broadcasts; and the growing importance of television. In one part of the world, however, these factors remained largely absent: Africa. As the twentieth century drew to a close, this lack of countervailing factors allowed a centrally controlled radio station to propagate one of history’s worst genocides.

In the late nineteenth century, in an effort to catch up with England and France, a newly unified Germany set its sights on East Africa, including the tiny colony of Rwanda, which consisted of a majority Hutu population and a substantial minority of Tutsis.

During World War I, the Belgians displaced the Germans. Critically, both colonial powers were influenced by the British explorer John Hanning Speke, who put forward the “Hamitic hypothesis.” This pseudoscientific racial theory postulated that lighter-skinned tribes with Caucasian-like facial features, such as the Tutsis, were superior to more Negroid-appearing tribes, such as the Hutus. (Ham, the accursed son of Noah, was said to have migrated south to Africa; Europeans, Americans, and Arabs frequently invoked this biblical curse as a justification for the slave trade.)

Before the 1950s, the Hutus and Tutsis had gotten along reasonably well, and because of frequent intermarriage it was often difficult to discern to which group an individual belonged. This did not stop the Belgians from issuing identity cards labeling Rwandans as one or the other, or from assigning the best jobs to the Tutsis, who were told, “You whip the Hutus or we will whip you.”54 The resultant Tutsi repression of the Hutus produced, for the first time in Rwandan history, widespread interethnic violence. The approach to independence in 1962 saw spasms of slaughter. Between 1959 and 1967, Hutus killed twenty thousand Tutsi, and hundreds of thousands of the latter fled.

Hard economic times typically breed political and racial conflict, as occurred in Germany in the 1930s. After 1967, life in Rwanda quieted down for a while, but in the late 1980s, prices for the nation’s coffee and tea exports fell; the resultant economic dislocation heated up its simmering ethnic cauldron. Over time, the Hutus regained power, and in 1990, the Tutsi reaction to the new Hutu domination erupted into outright civil war, which pitted the forces of the Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) rebels, mainly the children of those who had fled the slaughter of the early 1960s, against the Hutu-led national government of President Juvénal Habyarimana. There were similar events in neighboring Burundi, where in October 1993 Tutsi officers assassinated Melchior Ndadaye, the country’s first democratically elected president—a Hutu—and triggered anxiety among Rwandan Hutus that their Tutsi countrymen would turn on them, too.

On April 6, 1994, Rwanda’s President Habyarimana, Burundi’s new leader, Cyprian Ntayamina, and several of the latter’s cabinet were returning home from a regional trip on a Falcon 50 business jet. When the plane was on its final approach to the Kigali airport, witnesses saw two missile launches; both missiles struck the aircraft, which crashed into the presidential palace and killed all aboard.

The attack, which probably had been orchestrated by Hutu extremists, signaled the start of the genocide. During the initial phase of the civil war in 1990, Hutus had killed perhaps a few thousand Tutsis in isolated massacres, but within four months of the plane crash, approximately eight hundred thousand Rwandans—mostly Tutsi, but also Hutu “collaborators”—fell victim to one of history’s most horrific slaughters. Initially interpreted by the outside world as a typical spasmodic outbreak of African tribal violence, it was no such thing; it had been planned years in advance by the Hutus. The killing began literally within minutes of the plane crash.55

In Rwanda, two media outlets drove the genocide. The first, Kangura, a militantly anti-Tutsi newspaper run by journalist Hassan Ngeze, gradually stirred the genocidal pot for several years prior to 1994. The paper’s main message could be loosely translated as “Hutu-ness.” Its credo, the Hutu ten commandments, laid out the seductive danger of Tutsi women, the dishonesty and treason of Tutsi men, the way the Tutsis secretly controlled the nation, and the actions to be taken against them. The most often quoted of the commandments, number eight, stated, “Hutus must stop having mercy on the Tutsis.”56

The semiofficial Radio-Télévision Libre des Milles Collines (“Free Radio-Television of the Thousand Hills”), RTLM, triggered and directed the actual slaughter that followed the death of President Habyarimana. RTLM was set up as a private corporation with low-priced shares widely held among the Hutu population; its programming, unlike that of the ponderous state-run Radio Rwanda, was laced with lively music, off-color jokes, edgy disk jockeys and announcers, and interviews with ordinary citizens. The station quickly commandeered listeners, personnel, and funding from its state-run sister station.

Its primary product, though, was a murderous hatred of Tutsis nearly identical to Kangura’s. The spew could be diffuse and general: the demonization of Tutsis as thieving, sexually and financially predatory “cockroaches,” usually coupled with exhortations for their murder, both individually and en masse, such as the chilling, oft-repeated rhetorical question, “The graves are only half filled. Who will help us fill them?”57

RTLM could also supply highly specific guidance: the Hutu guards manning this particular checkpoint should be on the alert for a specific Tutsi vehicle approaching it; that group of Tutsis had hidden on one specific hill or another. After the targets had been murdered, the RTLM announcer would congratulate the perpetrators. The radio station also warned Hutus when foreign observers were about, and told them to refrain from killing until the all-clear was given.58 The most popular announcer, Kantano Habimana, harped constantly on the Tutsi’s fondness for milk, riches, and Hutu women; his mention of a specific Tutsi name was tantamount to a death sentence. In the words of Major General Roméo Dallaire, the Canadian commander of the United Nations peacekeeping force, “The haunting image of killers with a machete in one hand and a radio in the other never leaves you.”59

The outside world did almost nothing to stop the genocide, which essentially ended, at least in Rwanda itself, only when the RPF, spurred on by the murder of their fellow Tutsis, overran the last Hutu positions around the capital, Kigali, in July 1994. Although the genocide largely stopped within Rwanda’s borders at that point, for two more years Hutus continued to murder Tutsis in refugee camps in eastern Zaire, with the knowing connivance of President Mobutu’s government and the unwitting support of Western aid agencies and the United Nations. Only when Zaire began expelling and murdering its own indigenous Tutsis in 1996, did Rwanda’s new Tutsi president, Paul Kagame, decide he had had enough; with assistance from Zairean insurgent Laurent Kabila, Rwandan troops invaded eastern Zaire, cleared the murderous camps, and brought the remaining Tutsis back home.60

Why did the world stand aside? First, it did not monitor RTLM closely and thus only dimly perceived the power of its murderous tone and content. One Westerner who understood was General Dallaire; he repeatedly and unsuccessfully asked for permission to jam it. Writing years later, he pointed out that if such tragedies are to be prevented in the future, international monitoring of radio broadcasts in civil war zones will prove key. One of his major regrets is that he did not destroy RTLM’s transmitters.61

After April 6, 1994, the withdrawal of almost all Westerners from Rwanda compounded the tragedy. The memory of the gruesome deaths of eighteen United States soldiers in the Somalia “Blackhawk Down” incident, and the even more gruesome treatment of their bodies afterward, remained fresh in American minds. As early as January 1994, three months before the plane crash triggered the genocide, a Rwandan government informant revealed to Dallaire the outline of the Hutu strategy: they would provoke the murder of some Belgian troops, the backbone of the UN mission, and thus would trigger the withdrawal of the peacekeepers. Directed by the informant, the peacekeepers discovered several Hutu weapons caches.

In a famous “genocide fax” to his superiors in New York on January 11, 1994, three months before the fateful crash of the presidential plane, Dallaire outlined the plot and asked for permission to destroy the weapons caches; Kofi Annan, who at the time supervised UN peacekeeping activity, not only refused Dallaire’s request but actually ordered Dallaire to betray the name of his informant to the then Hutu-led government. (Annan compounded his shame three years later, when, as secretary-general, he ordered Dallaire not to testify before the Belgian senate investigation into the UN’s role in the catastrophe.)62

Events ran precisely according to the Hutu plan. After the shoot-down, the Hutus fabricated the story that the Belgians had ordered it, and on this pretext hacked to death ten Belgian soldiers. The rest of the Belgians and, along with them, most of Dallaire’s peacekeepers and almost the entirety of Rwanda’s foreign population, then left. The UN ordered Dallaire’s rump force not to protect Tutsis, but rather to guarantee the safe evacuation of foreigners.

The virtual absence of Western observers sealed the Tutsis’ fate. At the time of the shoot-down, only a very few journalists—mainly freelancers—reported from Rwanda. Afterward, numerous correspondents did accompany RPF forces as they invaded, but their association with the RPF prevented them from directly witnessing any of the atrocities. One reporter did operate independently: Englishman Nick Hughes, who carried with him a small video camera. On April 11, 1994, he climbed to the roof of the French school in Kigali, and, unobserved by the Hutu militiamen below, he shot a heartrending recording of their cold-blooded, almost casual, murder of several captive men and women. This was one of only a small number of extant recordings of the actual genocide.63

Although Hughes’ footage and other news of atrocities seeped out fairly early in the genocide, the Western media reported it as yet another example of spasmodic African tribal violence. At the time, they had bigger fish to fry; the genocide began just before the O. J. Simpson case broke. Even Tonya Harding, a disgraced American Olympic ice skater, got more airtime on American network TV than the events unfolding in Rwanda.64

Hughes described the significance of his footage with eloquence and poignancy:

I know now that what I saw was human evil in majesty. Many of those who were there later felt a bond—a need to explain what had happened to anyone who would listen. . . . These images are among the only known pictures of the genocide and they are shocking. In a sense, they are the only reminders that this event really happened. If only there had been more such images.65

It’s all too easy to assign a particular genocidal tendency to the Hutus, or for that matter to Germans, Serbs, or the Khmer Rouge. Sadly, under the appropriate circumstances, nearly all humans, and every race or ethnic group, may participate in genocide; one of the most bloodthirsty RTLF announcers was a Belgian, Georges Ruggiu.66

Hannah Arendt first called attention to this “banality of evil” in her famous Eichmann in Jerusalem. Laurence Rees, in Auschwitz: A New History, described in detail how a well-structured institutional environment can condition human beings to treat the industrialization of death as ordinary and even laudable, like the making of computer chips or fitness training. Rees found that death camp personnel, almost to a man or woman, considered themselves good people doing important work. In the 1960s and 1970s, psychologists Stanley Milgram and Philip Zimbardo cemented this concept with a series of experiments in which subjects were coaxed with frightening ease to administer brutal, and in some cases “fatal,” punishment to innocent strangers.67 Or, as put most simply by Holocaust survivor Primo Levi, “It happened, therefore it can happen again . . . and it can happen everywhere.”68

In the mid-1990s, modern two-way communications technologies, such as fax machines, cell phones, and personal video cameras, were rapidly spreading throughout the developed world. Not so in Africa: in 1994 through 1996, video cameras were scarce in both Rwanda and Zaire, and, as Nick Hughes implied, the genocide might well have been stopped had more images gotten out. Rwanda’s singular misfortune was that its 1990s genocide took place in a 1960s communications milieu.

Tragically, both the Nazis and the Rwandan Hutus well understood the despotic and murderous potential of radio. Behind the Iron Curtain, on the other hand, the Soviet Union mismanaged radio in so astounding a way that it would contribute to its eventual downfall.