8

THE COMRADES WHO COULDN’T BROADCAST STRAIGHT

N. I. Stolyarova rushed in to report that a Russian edition of The First Circle had appeared in the West; she also whispered in my ear that a way had been found to take a microfilm of the Gulag text abroad on Pentecost, in a week’s time. Our hour was striking, high up on an invisible bell tower.—Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn1

Would there be the earth without the sun?—Lech Walesa commenting on the role of Radio Free Europe in freeing Poland from communist rule.2

In the 1970s, most Russians did not question the safety of the nuclear power plants that sprouted around the Soviet Union. Their faith was not daunted by the near disaster at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania in 1979, for they thought the Western media coverage was overblown. As a technician from the Ukrainian town of Pripyat, which housed the reactors, explained, “There is more emotion in fear of nuclear power plants than real danger. I work in white overalls. The air is clean and fresh; it’s filtered most carefully.”3

Later, by the spring of 1986, Pripyat, fifty miles north of Kiev, and its immediate environs bustled with nuclear power activity, and the boomtown and its surrounding area burgeoned to nearly fifty thousand people. The city’s economic life centered on its four operating nuclear reactors and the construction sites of two more; when completed, the complex was to be the world’s largest producer of electricity, capable of lighting every home in England.

Reduced to their essence, most nuclear power reactors are water heaters that produce steam that spins turbine blades that, through the magic of Maxwell’s equations, yield electrical power. As long as the water is flowing, all is well. But in a cascade of accidents, poor planning, inadequate design and training, and simple bad luck, at 1:23 AM on Saturday, April 26, 1986, the water stopped in Pripyat. Uranium fuel rods overheated and melted; the facility officially known as the Chernobyl No. 4 reactor exploded and sent a fireball high into the night sky.

The human and technical dimensions of the tragedy—the dozens of firemen and technicians who died almost immediately after heroically keeping the blaze from reaching the other three reactors, the thousands more poisoned by radiation, and the vast swath of territory around Pripyat permanently abandoned—need no amplification here. For our purposes, the most remarkable aspect of the episode was the government’s initial concealment of the explosion itself from the populace, and when that was no longer possible, the clumsy attempt to hide its catastrophic consequences.

The world first became aware of the nuclear accident when a radioactive plume borne on the prevailing southeasterly winds arrived thirty-six hours later over southern Sweden at an altitude of five thousand feet. The Swedish air force, which routinely swept the nation’s skies for radioactivity, detected it first. Later, on the morning of April 28, a worker at a Swedish reactor detected radioactivity on his work boots; his coworker’s clothing soon tested positive as well, and so the plant’s managers ordered it evacuated, and motorists were kept away from its vicinity.

Soon enough, Swedish authorities measured radioactivity falling in snow and rain all over the country and deduced the Soviet Union as its source. Early on the evening of April 28, Swedish diplomats in Moscow made inquiries. The Soviets stonewalled them, but a few hours later a Moscow television news show made a brief four-line announcement, buried under several preceding upbeat economic stories, about “an accident” at Chernobyl. Although this apparent lack of emphasis amazed Western observers, Soviet citizens, attuned to the finer nuances of official pronouncements, clearly understood that the announcer’s terse, grim delivery portended a major disaster.4

The tragically inadequate governmental response to the Chernobyl disaster flowed inevitably from the central characteristic of all communist regimes: the instinctual control of information. In response to the explosion, the plant’s director, Viktor Bryukhanov, cut almost all telephone connections to the outside; on the day of the accident, in order to calm the public, news officials bragged that sixteen couples had been married in Pripyat. Satellite photos showing a soccer game in progress less than a mile from the burning reactor appalled American intelligence analysts.

The local apparatchiks did not even caution residents to remain indoors on April 26, and they did not evacuate Pripyat until the next day, April 27. Four days later, on May Day, Kiev’s party leaders refused to cancel the traditional parade, in spite of the radioactive winds blowing toward the city. While Europeans a thousand miles away furiously rinsed and scrubbed produce, Soviet citizens a dozen miles away took no special precautions with their food, and almost no one, save for a few high-ranking party officials, was issued the potassium iodide tablets that would have prevented thousands of subsequent thyroid cancers. Not until two weeks had passed did General Secretary Gorbachev address the nation. Even then, he barely hinted at the full extent of the disaster.5

As usual, the general secretary was behind the curve; almost from the first, most Soviet citizens had learned the awful facts of the accident from “the Voices”: the BBC, Radio Liberty, Voice of America, and Deutsche Welle.6 Information about the accident also spread through informal domestic channels, especially in the scientific and engineering community.7

The Chernobyl disaster was merely a symptom of more serious rot at the core of the Soviet Union. Five years later, the country collapsed abruptly from within, surely one of the most singular, mystifying, and almost totally unpredicted events in modern political history. As such, the implosion is something of a Rorschach blot that reveals more about the observer than about the event.

To his admirers on the American right, Ronald Reagan deserves the lion’s share of the credit. The Gipper, after all, had labeled the Soviet Union an “evil empire” and challenged Mikhail Gorbachev to “tear down this wall,” thereby capturing the high moral ground. Reagan rapidly built up the United States’ military might, initiated the “Star Wars” missile defense program, and, according to this narrative, snookered the Soviets into an arms race they could ill afford.

To be sure, most historians would single out the equally remarkable story of Gorbachev, who in 1985, following the deaths of Leonid Brezhnev, Yuri Andropov, and Konstantin Chernenko, became the fourth general secretary of the Communist Party within twenty-eight months. Gorbachev sincerely believed that the two policies of perestroika (roughly, restructuring) and glasnost (roughly, openness) would save communism; instead, these two initiatives hastened its end.

To the petroleum economist, the seminal events were the rapid rise in crude oil prices after the 1973 and 1979 oil crises, followed by the equally impressive fall in prices of crude in the early 1980s. The 1970s price rise pumped badly needed revenue into the Soviet Union and granted its tottering governmental system approximately a decade’s reprieve; the 1980s price fall knocked the last remaining prop out from under it and rang the curtain down on the grand seventy-year experiment. The 1970s rise in oil prices treated eastern European satellite nations, which had to import Russian petroleum, less well. Although the Soviets did subsidize these imports, in the long run eastern Europe could not be insulated from the oil shock that affected the rest of the global economy, and so communism’s end was hastened there as well.8

The military historian would surely focus on the cliff-hanging tactical events surrounding the August 1991 coup against Gorbachev by a small, incompetent group of KGB and army diehards. They neglected to arrest the Russian president, Yeltsin; did not completely secure the television and radio stations; and catastrophically failed to muzzle the media’s rebellious reporters and producers. Had they been more scrupulous about these things, the Soviet Union might still be around today.

Finally, a political scientist or an aviation expert would point out the remarkable bit of airmanship executed by a wayward German youth, Matthias Rust. On May 28, 1987, Rust, with just fifty hours of flying experience, piloted a small Cessna with dicey internal fuel tanks the almost six hundred miles from Helsinki to Moscow and deftly landed the aircraft in Red Square, where he informed the crowd that he had come to see Gorbachev about world peace. Although the Soviet leader outwardly expressed rage at the incompetence of his military, Rust’s stunt allowed him to sack much of the obstructionist, hard-line defense establishment and thus advance perestroika and glasnost.9

Reagan, Gorbachev, the price of oil, the incompetence of the coup plotters, and Rust all performed their part, but from the broader perspective, all the events that precipitated the fall of communism revolved around the control of communication, information, and news. Two simple technologies —carbon paper and shortwave receivers, both of which the Soviet command economy produced in incomprehensibly enormous quantities—lay at the core of the collapse of the Soviet Union and its eastern European empire.

The closer the observer was to the centers of Soviet power, the more strongly he or she emphasized the importance of the Voices. The sentiment of Lech Walesa expressed in one of this chapter’s epigraphs is clear enough. Gorbachev told Margaret Thatcher that the impulse for reform came from the desire for freedom, which in turn came from the Voices. Boris Yeltsin spoke more specifically about Radio Liberty: “This radio station reports objectively and fully, and we are generally quite thankful to them.” In the days leading up to the August 1991 coup, he had one of his aides fax a message to allies in Washington:

The Russian Government [as opposed to that of the USSR] has NO way to address the people. All radio stations are under control. The following is [Boris Yeltsin’s] address to the Army. Submit it to the U.S.I.A. [U.S. Information Agency]. Broadcast it over the country. Maybe “Voice of America.” Do it! Urgent!10

Václav Havel noted, “If my fellow citizens knew me before I became president, they did so because of these stations.” When Radio Free Europe’s funding got slashed in the 1990s and it could no longer afford its quarters in Germany, Havel gave it a home in Prague.11 The irony of the almost universal reverence for the Voices behind the Iron Curtain is that many in the West distrusted them; Senator William Fulbright labeled them Cold War relics, creatures of the United States government and CIA, and tried to shut them down.12

The best place to begin any understanding of the fall of communism is a brief essay written by the Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek, recently elevated, along with Milton Friedman and Ayn Rand, to near-sainthood by the neoliberal right. His most brilliant insight was encapsulated in “The Use of Knowledge in Society,” a short article published in American Economic Review in 1945. Its intellectual appeal extends far beyond libertarian circles.13

The problem in consciously structuring any economic system, Hayek saw, was that there are just too many moving pieces: a myriad of goods and services, each offered by diverse individuals and organizations. Consider just one industrial commodity: ball bearings. The world’s largest national economies consume approximately one hundred thousand different kinds of the tiny spheres; the manufacture of each takes multiple steps. The total material ensemble of any economy is thus so numbingly complex that its efficient organization lies well beyond the smartest planners in possession of the most detailed data and wielding the most powerful computers and sophisticated software. As put by Hayek:

The “data” from which the economic calculus starts are never for the whole society “given” to a single mind. . . . The [data] never exists in concentrated or integrated form, but solely as the dispersed bits of incomplete and frequently contradictory knowledge which all the separate individuals possess.14

Hayek’s special genius lay in the realization that the millions of individuals participating in a smoothly running economy communicate by means of the information inherent in prices—the “price signal”:

Assume that somewhere in the world a new opportunity for the use of some raw material, say tin, has arisen, or that one of the sources of supply of tin has been eliminated. It does not matter for our purpose—and it is very significant that it does not matter—which of these two causes has made tin more scarce. All that the users of tin need to know is that some of the tin they used to consume is now more profitably employed elsewhere, and that in consequence they must economize tin.15

The cynic might say that all Hayek had done was to provide a fancy description of Adam Smith’s famous “invisible hand,” the ability of the markets to arrange automatically for the efficient provision of goods and services. Perhaps—but in 1945, capitalism’s record over the previous two decades, especially during the worldwide Great Depression, did not inspire confidence. By contrast, the Soviet Union’s economy, far from collapsing, seemed to be rapidly overtaking the free market economies of the liberal democracies. As late as 1975, the usually astute Daniel Patrick Moynihan wrote an essay that pronounced the capitalist liberal democracy an endangered species.16 By the mid-twentieth century, the world desperately needed reminding of the existence of Smith’s invisible hand and of how it worked.

In 1945, Hayek saw that the best way to determine the output of bread or steel was to allow producers to observe prices, and then simply let those prices guide output. If bread became more expensive, then bakers would automatically turn out more loaves; if steel became cheaper, then plant managers would, without prompting from anyone else, shut down some blast furnaces.

The Soviet economic system, in contrast, mandated a certain fixed level of output, and a fixed price, for every single commodity. The results were a shortage of wearable shoes, and bread loaves whose cost had not changed for decades and which consequently had become so relatively cheap that they were commonly (and illegally) fed to livestock. (Contrary to the popular image, the Soviet Union was actually the world’s largest shoe manufacturer, but the shoes were of poor quality, style, and fit: “torture for the feet,” in the words of one Russian acquaintance, who added, “Italian shoes made me feel like a Cinderella story miracle.”)17

Western visitors to the Soviet Union marveled at the low prices of food staples, low rents, and low fares on public transport—prices that had, of course, been fixed by the authorities. What went unnoticed was that the state mandated even lower wages, and thus made these goods, when they were available, often unaffordable. In a normal market economy, wages constitute approximately two-thirds of gross domestic product; in the Soviet Union, wages constituted only one-third. The absence of a meaningful price signal proved especially damaging in the labor market, where a truck driver might be paid two to four times as much as a physician; in the sexist Russian society, this meant that highly skilled but poorly paid cognitive work, such as medicine, engineering, and teaching, became highly feminized. (The official pay of Russians often represented only a small portion of their actual recompense; access to consumer items was a key perquisite of party membership. Even for nonmembers, vocational access was a critical component of compensation: the teacher could solicit bribes from pupils’ parents, the doctor from her patients; and the construction foreman could pilfer prodigious amounts of materials.)18

The communist nations thus attempted to run a system devoid of the price signal, and they failed miserably. Their governments demanded that factories crank out this many tons of steel and that many liters of cooking oil, whether these were needed or not, no matter what their quality, and whether or not they could even be transported to consumers. The result: milk that spoiled before it reached stores, steel so pocked with defects that it could not be used in cars, and soap supplies that swung between severe prolonged shortages and massive surpluses that saw mounds of it dissolving in the rain.19

Worse, the belief in an economy run by a planning elite in possession of the “complete” set of data inevitably leads those who control this vital information to deprive others of it, no matter how innocuous the information. In the Soviet Union, among the most sought-after items brought in by foreigners were street maps of Soviet cities created from Western satellite photos; the ones produced by the domestic cartographers had been intentionally distorted to the point of uselessness, presumably for military reasons. Increasingly, the official information itself was falsified, all too often rendering the planning process worse than worthless.20 And if city maps were dangerous, then political opinions, or even literature, must surely carry mortal peril.

At the same time that Hayek wrote his famous essay, a mathematician, Norbert Wiener, considered the use of information in society from a somewhat different angle. Unlike Hayek, Wiener, who hailed from a highly intellectual midwestern Jewish-American background, held a jaundiced view of capitalism, which he saw as both inefficient and unjust. He earned a PhD in mathematics from Harvard at the astounding age of eighteen, and during World War II found himself working on the problem of the radar control of antiaircraft fire.

Researchers quickly realized that the solution to the problem of antiaircraft fire lay beyond even the sophisticated ballistic calculations normally used for artillery, and that automatic, rapid devices were called for: thus the first primitive electronic computers. Wiener recognized that such computational methods carried with them enormous implications for medicine, physiology, economics, and the very structure of human society. He gave the new field of study a name: cybernetics, the theory of information and control in human and animal systems.21

With stunning prescience, Wiener foresaw a “second industrial revolution,” during which information, mediated by mass-produced computers, would become at least as important as manufactured goods. Wiener’s foresight, in an era that had only a few room-size vacuum-tube computers tended by small armies of technicians, has worn well. While IBM’s founder Thomas Watson, contrary to popular legend, probably never said, “I think there is a world market for about five computers,” this apocryphal statement did accurately reflect the public perception of computers in the pre-PC era. In short, Wiener imagined a world in which

That country will have the greatest security whose informational and scientific situation is adequate to meet the demands that may be put upon it. . . . In other words, no amount of scientific research, carefully recorded in books and papers, and then put into our libraries with labels of secrecy, will be adequate to protect us for any length of time in a world where the effective level of information is perpetually advancing. There is no Maginot line of the brain.22

Put into plain English, in a world where technological progress and military security depend on constant scientific advance, secrecy, far from maintaining national security, actually erodes it by preventing the intellectual cross-fertilization that characterizes open societies. While the anticapitalist Wiener aimed his concerns about secrecy at what he saw as the absurd precautions of the American military-industrial complex, they applied in spades to the Soviet Union.

The Soviets well understood the ominous economic and political implications of Wiener’s writings, which were enormously popular and influential in the West. As expected, the Russian propaganda machine inveighed mightily against the philosophical and economic aspects of cybernetics, which it labeled a “pseudoscience.”23 Outwardly, Stalin’s henchmen mocked cybernetics:

The process of production realized without workers, only with machines controlled by the gigantic brain of the computer! No strikes or strike movements, and moreover no revolutionary insurrections! Machines instead of the brain, machines without people! What an enticing perspective for capitalism!24

Although the Soviets disdained Wiener’s new science—it did not help that he was Jewish—his vision of a postindustrial world suffused with cheap, easily available information-crunching machines must have petrified them, since they could not help noticing the ability of the new devices to copy information. (While the Soviets dismissed Wiener’s work publicly, they were not so thick as to prevent their military from incorporating cybernetic theory into their missile technology.)25

For centuries Russia, geographically far from the center of the European Enlightenment, found itself constantly playing intellectual, cultural, technological, and economic catch-up with the West. Periodically, visionary leaders such as Peter the Great and Catherine the Great attempted radical modernization. Peter traveled incognito through western Europe early in his reign as czar, visited the Sorbonne, and learned, among other things, the shipbuilding techniques of the Dutch East India Company; Catherine began her life as the highly educated daughter of a German prince and attempted to align Russian culture and government with the French model.

All modernizing Russian leaders, from Peter through Catherine to Gorbachev, faced the same problem, which historian James Billington called the “dilemma of the reforming despot”:

How can one retain absolute power and a hierarchical social system while at the same time introducing reforms and encouraging education? How can an absolute ruler hold out hope for improvement without confronting a “revolution of rising expectations?”26

After 1950, Billington’s “revolution of rising expectations” slowly eroded communist regimes’ grasp on absolute power on a variety of communications battlefronts. The relevant mechanisms ranged from the handwritten copying of seditious novels to the miniature shortwave radio that kept a captive Mikhail Gorbachev apprised of the coup plotters’ weaknesses. In the second half of the twentieth century, the peculiar development of the Russian radio industry would combine with simple copying technologies to break the government’s stranglehold on information in the Soviet Union and its eastern Europe satellites.

The contributions of carbon paper and radio to the downfall of communism in the Soviet Union and its eastern European satellites were not merely additive. These two media yielded political synergies that no one foresaw; their potent combination snowballed over the decades and exceeded the most optimistic hopes of these nations’ repressed populations and the worst nightmares of their rulers.

The Soviet audience differed from that in the West, and particularly from that in the United States, in at least four essential ways. First, Russians take their authors and poets far more seriously, and these writers occupy a far loftier place in the public consciousness. When political expression is suppressed, literature becomes the main political outlet. As put by the Russian essayist Osip Mandelstam, “Only in our country is poetry respected—they’ll kill you for it. Only in our country, and no other.”27 Shortly after he uttered this sentiment, he died for his writings.

Second, because the rulers of the Soviet Union restricted news from abroad, Russians became intensely interested in it, far more so than people in the United States, a nation in which almost no one—including at least one former president—knows the difference among Slovakia, Slovenia, and Slavonia.

Third, in Stalin’s time the authorities generally granted ordinary workers more autonomy of thought and action than intellectuals and party officials. One famous story has a young woman factory worker being told by a panel of bosses that she must work overtime without pay. She turned her back to her seated bosses, lifted up her skirt, and said, “Comrade Stalin and all you can kiss me wherever it is most convenient for you.” For a very long moment, the commissars sat pale, silent, and frozen with fear, until one elicited nervous laughter with, “Did you notice she didn’t have any [under]pants on?”28

Fourth, after Stalin’s death, the asking of “sharp questions”—a particularly Russian pastime—became more acceptable, even fashionable, particularly at the highest political levels and at elite universities. One American exchange student at Moscow University in the early 1960s, William Taubman, noted that students reserved the most acid ridicule for their peers who routinely mouthed Marxist cant; contrariwise, those who could flummox instructors and political officials with clever cross-examination earned high esteem.29

Along with radio and the dramatic steam- and electricity-driven improvements in printing, a quieter revolution in the reproduction of the written word was taking place that would destabilize the communist world: the development of inexpensive mechanical copying.

Technically speaking, the printing press is a duplicating machine, not a copying machine; the former makes multiple identical document copies from a mechanical template, whereas the latter makes copies of an original document that may often vary greatly among themselves. For thousands of years, cheap human clerical labor had provided the most economical way of making replicas of a letter, pamphlet, or book—that is, copying it by hand.

In 1603, a German Jesuit, Christoph Scheiner, built a device based on Euclidian geometry that made more or less exact duplicates, as well as enlargements and reductions, of writing and drawing; he named it the pantograph. Over the next two centuries, the temperamental, expensive device evolved in the hands of multiple inventors; its final form, the “polygraph,” could produce up to five copies at once.

As late as the early nineteenth century, clerks still cost less than fickle, complex polygraphs and pantographs, which remained largely the province of enthusiastic first adopters such as Thomas Jefferson, who owned several pantographs. A prodigious inventor in his own right, he was obsessed with the fragility of the information chain in the preindustrial age. In a letter to historian Ebenezer Hazard, Jefferson fantasized:

Time and accident are committing daily havoc on the originals deposited in our public offices. . . . Let us save what remains: not by vaults and locks which fence them from the public eye and use, in consigning them to the waste of time, but by such multiplication of copies as shall place them beyond the reach of accident.30

Jefferson would surely have mightily approved of the Xerox machine and the personal computer, devices that allow the nearly infinite copying of information, but in the late eighteenth century, the pantograph was all he had, and it was not up to the task.

Jefferson had no way of knowing just how prescient he was. Even in that era, scholars had noted how some documents yellowed, became brittle, and fell apart; by the early twentieth century document self-destruction reached epidemic proportions. Many observers blamed atmospheric pollution from industrial activity, but it fell to William Barrow, an autodidact who was worried that he would not be able to preserve family documents, to uncover the problem’s multiple causes. Although he possessed only an associate degree, Barrow managed to acquire sophisticated mechanical testing equipment and assembled a talented team of materials scientists to solve the mystery of the decomposing books.

The trouble, Barrow found, began even before Gutenberg, when scribes, and then printers, gradually converted from carbon-based to iron gall inks. If the printer added too much tannic acid to the brew, the highly acidic written and printed letters would slowly eat through and shred the page. As high-quality cotton rags became more scarce, papermakers started to bleach their darker, dirtier raw materials with chlorine. This made for more acidic paper, which became increasingly brittle over time.

Nothing, though, savaged the integrity of books like the switch in the 1880s from cloth to wood pulp, which required the use of harsh chemicals that could yield either a highly acid, or, less commonly, a highly alkaline, product. In the late 1950s, Barrow examined five hundred books, one hundred from each decade between 1900 and 1950. The results stunned him; within decades, the paper became weak and brittle; sheets that could be folded hundreds of times when new cracked and tore when bent only half a dozen times. Barrow went on to invent a restorative process now used by librarians around the world, and he also helped develop today’s industry standard acid-free paper.31

Other modern media suffer from even more severe problems. The earliest nitrate films spontaneously combusted; later acetate reels suffered from “vinegar syndrome,” a term referring to the characteristic odor that accompanies their degradation; and Technicolor film generally fades into uselessness within a few decades. Film historians estimate that more than 90 percent of silent films, and more than half of films made after 1950, have been lost forever. (In addition, at least as many of the earliest films were lost by careless archiving and simple discarding as by degradation.)32 Finally, as mentioned in Chapter 1, today’s digital media may prove even more ephemeral, not only because of degradation but also because of format obsolescence.

History best remembers James Watt as the inventor of the first steam engine efficient enough for practical use, but he also devised the nineteenth century’s preeminent copying method, whose use survived well into the twentieth century.

Watt, like any other successful businessman, desired duplicates of his letters, invoices, and internal records. For millennia, scribes had known that a freshly inked document, when compressed evenly against another piece of paper, will transfer a reversed image onto it. Watt realized that if thin, moist paper received an impression from the original, under sufficient pressure the ink would wick evenly and completely through to the opposite surface of the copy, and thus produce a normal nonreversed image. Through trial and error, he found that adding a bit of sugar to the ink improved the result, as did, under the appropriate conditions, either a screw press or a roller press. In 1780, he patented his first roller device, which sold for £6, or about $400 in today’s currency. His devices, commonly known as “copying presses,” succeeded wildly; nearly all of the founding fathers, including Jefferson, bought them. (Jefferson’s purchases in 1789 for the nation’s new State Department became the American government’s first office copiers.)33

Copying presses grew in diversity and popularity. On the smallest scale, they could be primitive, portable devices consisting of blank pages and a small roller into which sequential copies could be impressed, compact enough to fit in a pocket. For high-volume office use, they could be large, complex machines. In the nineteenth century, the term “copying press” was applied, at one time or another, to nearly all of them. Today, the screw-operated copying press can easily be found in antique shops and on eBay.com, almost always mistakenly referred to as a “book press.”

The late eighteenth century and the early nineteenth saw the appearance of four more copying technologies. The first, lithographic printing, came about in 1795 when the mother of Alois Senefelder, a young German playwright, asked him to record the clothes sent for laundering; not having any paper handy, he wrote the list on a piece of polished limestone, using a waxy ink he had been experimenting with.

In a stroke of genius, he realized that while nitric acid would etch away limestone, it would not erode the surface protected by the wax. When he bathed his limestone laundry list in the acid, he was left with a raised impression protected by the waxy writing about a hundredth of an inch thick, and with careful flat polishing of the stone and meticulous printing technique his method yielded fine, clean copies. The technique he patented, lithography, represents a vital intermediate technology between the printing press and the copying press, capable of yielding large numbers of copies of handwritten documents and pictures. (Early printing presses could not easily reproduce drawn figures, since these presses required laborious manual production of each image, while copying presses could not generate copies of any sort in volume.)34

The second copying system was stencil duplicating; for centuries, it had been known that ink could be applied through a cut template, or “stencil,” to produce an image or writing. In the late nineteenth century, inventors discovered that writing with a stylus on waxed paper laid on a finely cut flat file plate yielded a punctuate image of drawings and letters. This technique was refined by multiple entrepreneurs, including Thomas Edison and a lumberman, Albert Blake Dick. The latter patented the famous mimeograph machine, whose trademark inscription “AB Dick” aroused giggles in generations of children allowed into the inner sanctum of their school’s copying room.

Older readers will remember rough copies of exams or worksheets printed in purple ink. Although usually called “mimeographs,” these copies were far more likely to have been examples of a third copying system, the hectograph. With this technique, originals were printed on paper with a thick wet ink, which was then applied to a moist flat gelatin plate. The ink that adhered to the plate could make scores of copies before it wore away; the term “hectograph” indicated that the plate could print up to a hundred copies, although this number was rarely achieved in practice.35

Russian and eastern European dissidents employed, at one time or another, all of the above copying technologies. Not infrequently, when none was easily available, they reverted to medieval scribal mode—hand copying. Among all copying technologies, however, a fourth nineteenth-century invention, carbon paper, deserves the greatest credit for bringing down communism.

The first primitive carbon paper was invented in 1806 by Ralph Wedgwood, grandson of the famous English potter Josiah Wedgwood. Ralph’s product, intended as a writing aid for the blind, consisted of a complex system of plates, styluses, and ink-soaked paper. The process involved four sheets: the “original” sheet on top, underneath which were stacked two more sheets with the double-sided inked “carbon” between them, thus yielding an original, a normal copy, and a reversed copy. Smelly and messy, Wedgwood’s technique found only scattered practical use.

But Wedgwood’s invention did find favor with the reporters and editors of the Associated Press (AP). In 1868, the AP covered the twenty-first-birthday celebration of a greengrocer, Lebbus H. Rogers, deemed newsworthy because the young man climaxed the festivities with a balloon ascent. In an interview in the AP offices afterward, Rogers spied the carbon paper; intrigued by it, he gave up aeronautics to pursue its business potential.

Flimsy quill pens could not inscribe high-quality carbon copies, and Rogers’ venture initially foundered. Sometime around 1873, he attended a demonstration of the first practicable commercial typewriter, manufactured by the gun and sewing machine maker E. Remington and Sons. Rogers found that the combination of carbon paper and typewriter could yield up to ten legible copies in expert hands; this method replaced the copying press, which by that point had served businessmen and writers around the world for more than a century. Even so, he had his work cut out for him, because by 1873, carbon paper technology had not evolved much beyond Wedgwood’s technique; in the ensuing decades, Rogers developed, then mechanized, a process for applying dry carbon black to only one side of a thin, durable paper sheet. Ever the polymath, by the time he died in 1932, he had written sonnets, run a ranch, invented wire-casing machinery, and observed with pleasure that his invention had become a mainstay of office copying.36

Had Rogers lived two more generations, he would have seen the typewriter and carbon paper trigger amazing events in Russia, for this combination made possible the relatively rapid, decentralized production of large numbers of copies, in which each duplication cycle could exponentially increase a book’s or a pamphlet’s circulation.

The history of Russian dissident and underground publishing goes back centuries, as Russia’s rulers understood, almost from the first, the subversive nature of words in totalitarian societies.37 In 1790, the author and social observer Alexander Radishchev wrote an anti-serfdom tract titled A Journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow. Although the police confiscated all the print copies they could find, handwritten manuscripts circulated widely; during the Decembrist revolt of 1825, Pushkin and others kept a low profile by avoiding the printing press and circulating their writings only in manuscript form. Throughout the nineteenth century and the early twentieth, homemade manuscripts and books printed on foreign presses proliferated in czarist Russia. The most famous of the foreign presses was Free Russian Press, founded in London in 1852 by the Moscow-born intellectual Alexander Herzen.

Before the Bolshevik victory in 1917, the revolutionaries produced the first carbon-paper-derived “Underwood copies,” named after the popular typewriter manufacturer. After the Bolsheviks gained power, they naturally suppressed this mode of copying. Carbon reproductions contributed to the 1938 death of Mandelstam, whose quote earlier in this Chapter about dying for poetry proved all too prophetic. The extreme repression of the Stalinist period made things too hot for even Underwood copies, and writers simply produced manuscripts v yashchick (“for the desk drawer”), to be read, if at all, by visitors to their homes.38

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who was imprisoned from 1945 to 1953, best described the spirit of v yashchick:

Without hesitation, without inner debate, I entered into the inheritance of every modern Russian writer intent on the truth: I must write simply to ensure that it was not forgotten, that posterity might someday come to know it. Publication in my own lifetime I must shut out of my mind, out of my dreams.39

Without pen and paper, the jailed Solzhenitsyn committed his novels, essays, and poems to memory, using beads and matchsticks as mnemonic aids. After Stalin’s death in 1953, the repression relaxed, and in 1956, two momentous and countervailing events rocked the communist world: the Twentieth Congress of the Soviet Communist Party and the political uprisings in Poland and Hungary.

During the Twentieth Congress, Khrushchev delivered a blistering “secret speech” that exposed the horrors of the Stalinist era; it was followed over the next several years by a loosening of censorship, increased cultural ties with the West, and even some modest economic liberalization. The CIA almost immediately obtained a transcript of the “secret speech,” which the Voices extensively rebroadcast; in response, the Soviets made its gist public after some delay, but they did not publish its full text until 1989, more than three decades later.

For several years after 1956, a literary and political thaw flourished under Nikita Khrushchev. In 1962 Solzhenitsyn used his bead-and-matchstick method to reconstruct and publish a novelistic account of prison life, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, in Novy Mir, an official literary magazine in the vanguard of liberalization. However, after Khrushchev fell from power in 1964, the gloves came off, and the authorities again began to pursue aggressively not only Solzhenitsyn, but other dissident writers as well.

Yuri Andropov, Russia’s ambassador in Budapest during the Hungarian political uprising, never forgot the sight of his agents’ bodies strung from the city’s lampposts, nor did he forget being fired upon by the revolutionaries as he moved about the city. Andropov concluded that from this point forward, the first signs of dissent anywhere in the communist empire had to be quickly and firmly crushed; within two years Imre Nagy, Hungary’s former premier, who had been promised a safe-conduct from his hiding place in the Yugoslav embassy in Budapest, was arrested, tried, and executed under the direction of the Soviets.

Over the coming decades these two paradigms—Khrushchev’s liberalization and Andropov’s repression—would do epic battle. The gradual ascendancy of the hard-liners was reflected in Andropov’s rise; in 1967, he became KGB head, the position from which he directed the 1968 smothering of the Prague Spring and the 1979 invasion of Afghanistan. In 1982, he was elected general secretary of the Party.

Thus, 1964 represents a watershed in dissident publication, and most authorities date the history of underground dissident publishing—samizdat, humorously referred to as “overcoming Gutenberg”—from approximately that year.

The term “samizdat” was said to have been coined in the 1950s when a Moscow poet, Nikolai Glazkov, whimsically wrote the word samsesbyaizdat—“publishing house for oneself”—on the front of a typewritten collection of his work in the place where the name of the publishing house would normally appear.40 The word can have multiple meanings: most narrowly, typewritten copies distributed from hand to hand; or more broadly, these plus copies made by other methods. Or, as the dissident Russian author Vladimir Bukovsky put it, “Write myself, edit myself, censor myself, publish myself, distribute myself, go to jail for it myself.”41

Other words share the same root: tamizdat, foreign printing of a dissident work, literally, “published over there”; radizdat, any material, including music, broadcast abroad and copied at home; and magnitizdat, materials, usually music, recorded on tape or cassette. (State-run publishing organizations carried similar names: Gosizdat and Politizdat.)

Samizdat, tamizdat, radizdat, and magnitizdat became woven together in a self-reinforcing cycle: written material was smuggled and then published abroad, broadcast over foreign radio, and retranscribed and recopied by Russian listeners. Unless the police could intercept the process within the first few copies, stopping this cycle proved impossible.

Julius Telesin, a dissident Soviet writer who emigrated to the United Kingdom, provided the classic operating description of samizdat.42 He begins his essay by playfully noting that the best place to plumb its murky beginnings would be in newspaper records of Stalinist trials, but unfortunately, the state “does not like its citizens to read old newspapers.”43

He then describes how samizdat closely resembles publishing in capitalist countries, but with a twist: in order for a work to be extensively reproduced, not only must it be well written and of wide interest, but it must not be too dangerous:

Samizdat is differentiated according to degrees and shades of danger. A man develops, consciously or intuitively, his own notion of the risk he is taking when he types out, gives people to read, or keeps at home, pieces of samizdat or tamizdat literature.44

Telesin then observes that the reader of samizdat copies, which are hand-produced and in high demand, may borrow his copy for only a few precious days at a time:

It is natural that I should want to keep this work for myself. But I have to return the copy I was given, perhaps very soon, as someone else is waiting his turn to read it. Consequently, I have to start looking for a way to copy the work.45

Were the manuscript short—say, several pages—no great problems would hinder copying: the reader would simply sit down at his typewriter for a few hours and bang out carbons for himself and his friends. But what if the work is longer—say, even a novel? First, as a matter of basic courtesy, permission for copying must be obtained from the manuscript’s source; second, a typist must be found; and finally, the manuscript will be needed for some extra days beyond the initially agreed-upon loan period:

At this point a certain amount of bargaining usually begins. It emerges that, as a “fee,” I must return the work plus three copies. The person who gave it to me wants one copy for himself; he will give another one to the person who gave it to him, but as the work belongs to a third person (as a rule names are not mentioned) the last wants an extra copy for himself (perhaps he will give it to someone as a birthday present). Then I declare that I am being “overcharged.” My friend’s typist can only do five copies—her old typewriter cannot “take” more. At the same time she wants a copy for herself, and my friend wants one too. Thus, if I give away three copies here and two there, what will be left for me?46

He bargains his source down to two copies; of the five he gets from the typist, she will—he hopes—take only one, thus leaving two for the original lender and two more for Telesin: one for himself, and one for “a certain person who is very much interested in the subject; besides, this person may be useful in getting hold of other things for me to read.”47

Telesin praises the beauty of the system: typewriters are cheap and no longer have to be registered as in Stalin’s time; plain paper and carbon paper, while occasionally in short supply, can be stockpiled. But since the mail is definitely not secure from the state’s eyes, copies must be passed from hand to hand.

Soviet and eastern European police failed to control adequately access to both typewriters and carbon paper. For example, while government departments sent print samples from all typewriters to the KGB, officials did not require and monitor the private sale and use of typewriters. Instead, the authorities tried to control the dissidents themselves, but once the first batch of carbon paper copies had been distributed, Rogers’ carbon paper genie had escaped the ink jar, no matter how many subsequent arrests were made.

Other techniques round out the samizdat process: to conserve precious paper, the typist employs a tiny font, single spacing, and the narrowest possible page margins. She—most typists were women—also uses onionskin paper that could yield as many as fifteen copies, the last of which was barely legible. In especially favorable circumstances, hectograph and mimeograph machines, sometimes homemade, were pressed into service as well. Once printed, a samizdat book or essay might even be bound; rarely, state printing facilities could be commandeered, and one group of Soviet Baptists even managed to run a clandestine printing press.48

The most critical phase of distribution involved the delivery of the copies into the hands of travelers and diplomats for publication abroad. Over time this proved the most effective channel of distribution, for it allowed the Voices to broadcast the most important samizdat texts into millions of homes, among which might be thousands more typists listening to and transcribing the broadcasts.

Even so, danger, expense, and shortage of trained and willing personnel dogged the process at every step: skilled typists, who could be easily intimidated with the threat of transfer to physical labor, were chronically in short supply, and printing and copying operations had to be shifted continually from location to location. All too often, those involved were repaid with arrest, beating, and imprisonment.

The final product was often threadbare and riddled with typographical and grammatical errors, yet this shabbiness lent the document a palpable credibility. As put by an anonymous Czech writer who went by the pseudonym Josef Strach (the surname translates as “fear”), samizdat publications were

a medium of communication which looks poor and miserable beside the fantastic rotary press and color television, but which is an unusually powerful and indestructible force. . . . It is written by someone who has something to say. . . . When I take it in my hand, I know that it cost someone a good deal to write it, without an honorarium and at no little risk.49

The tattered paper; crude, uneven print; and typographical and grammatical mistakes, amplified by repeated copying, actually increased the appeal and legitimacy of samizdat. At the very least, it was forbidden fruit. The sway of this bohemian shabbiness was so great that it served to delegitimize the slicker official press: the more attractive a book, the less believable it was. A popular Russian anecdote from the 1970s tells of a woman unable to interest her granddaughter in War and Peace because it looked “too official”; the grandmother finally gets the girl to read it by laboriously retyping it on cheap paper.

As put by one apparatchik in a private letter to friends,

A compulsory ideological diet is so tiring that today even an orthodox Soviet bureaucrat would read certain books if they happened to come into his hands. . . . What if The Gulag Archipelago was published. . . . How many would buy it? How many copies would be needed? Five, ten, maybe twenty million? A country of censorship does in truth pave the way for a whole army of thankful readers.50

Even the mere reading of samizdat could become a complex, conspiratorial activity. While the reproduction cycle for short essays might consume but a few hours, allowing the manufacture of thousands of copies in a week, the duplication of longer essays, novels, and nonfiction took more time; the resulting shortage of larger works led to nocturnal “reading parties” where pages would pass from hand to hand as they were read.51

In the Soviet Union, even during the repressive post-Khrushchev era, and particularly in the eastern European satellites, a younger generation—the students Taubman observed asking “sharp questions”—gradually assumed power from the old guard in the 1960s and 1970s. As this younger generation rose through the ranks, perhaps out of a feeling of guilt for their lack of courage compared with the dissidents, they gradually began to court their samizdat-empowered countrymen. By 1980, the process of democratic reform was nigh unstoppable.52

In 1956, Novy Mir refused to publish Boris Pasternak’s masterful Doctor Zhivago, which the author had begun not long after the Bolshevik Revolution. The next year, he had it smuggled out of the country; it became a best seller in more than a dozen languages. What did it say about the Soviet Union that the nation’s greatest living author had been forced to publish his finest work abroad, and what did that imply about what the Soviets did allow into print? If even the great Pasternak could not get Doctor Zhivago published in the Soviet Union, what hope did more daring novelists have of reaching the Russian audience by conventional means? When the authorities threatened Pasternak with expulsion and made him refuse the 1958 Nobel Prize, what did that say about the legitimacy of the regime itself?

Before the 1960s, Pasternak, Solzhenitsyn, and others like them attempted to work within the framework of the Writers’ Union; when it finally threw Pasternak and Solzhenitsyn out, in 1958 and 1969, respectively, expulsion became a badge of honor among the Russian literary elite.53

The other communication technology that empowered the citizenry of the Soviet Union was radio. How did radio, a centrally controlled, one-way technology that promoted totalitarianism in Nazi Germany, encouraged and choreographed genocide in Rwanda, and arguably concentrated power in the hands of the few even in the United States, help liberate Russians and eastern Europeans?

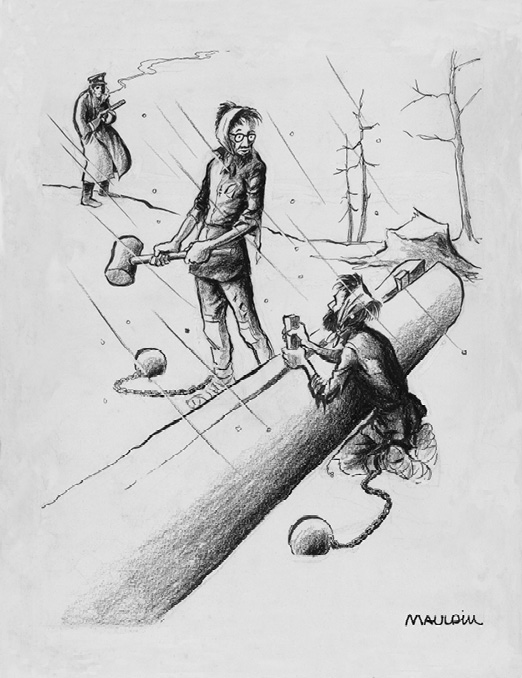

Figure 8-1. “I won the Nobel Prize for Literature. What was your crime?” Bill Mauldin did not win a Nobel for this 1958 cartoon, but it did earn him a Pulitzer the next year.

The remarkable answer is that the Soviet Union and Eastern European communist regimes inexplicably flooded their nations with millions of shortwave devices—machines that actually received foreign broadcasts better than those transmitted from within their own territory.

Immediately after the 1917 Revolution, the fact that the Soviet Union’s population was largely illiterate mandated an oral means of mass communication. It would take decades to deploy radio technology in Russia, so the leadership first pressed into service millions of “agitators”: farm and factory workers who served as unpaid, hardworking, problem-solving role models and regularly met with their peers to overcome production obstacles and to transmit the party line to the proletariat. In the 1920s and 1930s, while radio was burgeoning in America and Europe, agit-brigades crisscrossed Russia on agit-trains, performing musical numbers and plays at all stops.

In general, the agitators were neither highly literate nor ideologically sophisticated. They had little formal education; occasionally they might briefly attend special schools or meetings, but by and large they took their cues from party publications such as Agitator, which was aimed specifically at them.

In truth, the agitator was a throwback to an almost prehistoric “Dunbar’s number” society, where communication occurred face-to-face; by the 1930s, the agitators should have disappeared, but in true Soviet style, this archaic institution persisted almost until the collapse of the Soviet Union.54

In the United States and Nazi Germany, by the 1930s radios were household appliances and broadcasts reached most of the population; in contrast, Soviet radio production remained minuscule until well after World War II. The Soviets had also ignored radio for another reason; they had wired farms, factories, and most public spaces with a massive loudspeaker propaganda system that peaked at around thirty-five million outlets in the mid-1960s.

While Stalin lived, few Russians owned radios, and as in Nazi Germany, those who did listened to foreign broadcasts at mortal peril. After Stalin’s death, the authorities still frowned when citizens tuned in the Voices, but they rarely punished those who merely listened. To get arrested, a Soviet citizen usually had to take a step beyond simply hearing a foreign broadcast; depending upon the political pendulum, the repetition of foreign radio content, either orally or in print, might or might not result in prison time.55

Early in the Cold War, the Voices were of relative unimportance in the Soviet Union. When the Voice of America (VOA) began broadcasting to Russia in 1947, the country had only about 1.3 million shortwave receivers; as late as 1955, it had only about 6 million of them. Had the Soviets been smart, they would have kept it that way. Inexplicably, in the 1960s, they dramatically increased production. The precise reasons why they engaged in such a patently suicidal manufacturing enterprise may never be known. One possible explanation for the decision involves Russia’s vast distances and the government’s desire to minimize, for reasons of both cost and control, the number of radio transmitters. Alternatively, and more simply, massive centrally planned economies by their very nature tend to make massively irrational decisions; the commissars did not fully appreciate the downside to making the shortwave band the main broadcast conduit.

Whatever the reason, officials commanded the production of millions of sets per year, nearly all capable of receiving the Voices. The commissars had made a colossal, unbelievable blunder: they had given away their monopoly control of this powerful medium and supplied Western broadcast stations with a ready-made audience.

Recall that the Nazis designed only underpowered long- and medium-wave reception (150–1700 kHz) into their Volksempfänger and were smart enough not to include shortwave reception. To be sure, the Soviets prohibited the manufacture of sets capable of receiving some of the higher frequencies later used by the Voices, but in a nation amply endowed with engineers and hobbyists, anyone wishing to circumvent this prohibition had little problem doing so. The Bulgarian communist regime selected a devious middle course by offering radio owners free overhauls, after which the sets received only Radio Sofia.56

The Soviets compounded their error by developing a news service suffused with turgid ideological cant and so focused on controlling the information flow, particularly from abroad, that it provided the citizenry with almost nothing worth listening to. Frequently, news bulletins were written days or even weeks before being broadcast; why bother with the official radio station when the Voices provided both foreign and domestic news, with greater accuracy and currency?57

The West consciously took advantage of these circumstances. The BBC, which had begun its English international service in 1932, began to broadcast in Russian in 1946, and the United States soon followed with the creation of the Voice of America, the equivalent of the BBC foreign service, and “privately funded” services: Radio Free Europe (RFE), aimed at eastern Europe; and Radio Liberty (RL), aimed at the Soviet Union.

The eastern Europeans, being more prosperous and more technologically advanced than the Russians, adopted shortwave sooner. In 1956, workers at the Cegielski factory in Poznan´, Poland, rose up and demanded higher wages and the departure of Russian troops. An end to radio jamming was clearly an unvoiced demand, since when the factory’s workers took as their stronghold the local radio station, they smashed the transmitters used to jam Radio Free Europe and tossed the pieces out the window.

At the time, the head of RFE’s Polish Service was Jan Nowak, the remarkable “courier from Warsaw” who during World War II engaged in a years-long death-defying sojourn among the major centers of resistance to Nazi rule in Poland and London, the seat of the Polish government in exile.58 Nowak brilliantly handled Poland’s informational link to the West during the Poznan revolt. As put by one reformist Communist Party official, “Had RFE not told our people to be calm, I am not sure whether we alone would have managed to cope with the situation.”59

The events in Poland led to the return to power of the relatively liberal Wladyslaw Gomulka and inspired the Hungarians to implement similar changes; but when the Hungarians’ popular reformist leader, Imre Nagy, moved toward a multiparty democracy, declared the nation’s neutrality, and withdrew from the Warsaw Pact, the Soviets invaded. RFE served a similar role in Hungary as in Poland, but its Hungarian programming was not as tightly disciplined as that of Nowak’s Polish Service; while RFE did not directly incite the violent uprising, many of its broadcasts were later interpreted as giving Hungarians the impression that help from the West was on the way. As put by one observer, “[Never before has radio been] the principal means of communicating internal as well as external facts during a major national uprising.”60

In 1967, the American left-wing magazine Ramparts blew the cover off the funding of RFE and RL, which, in fact, had derived from the Central Intelligence Agency, just as the Soviets had long asserted. Far from discrediting RFE and RL, the CIA connection enhanced their credibility in communist nations, where intelligence services carried greater authority. (The revelation of CIA funding, however, did significant damage to morale at RFE and RL; as put by one staff member, “We were lied to.” The revelations also gave opponents of RFE and RL, most notably Senator Fulbright, ammunition in their campaign to close them down. Fortunately, the more conservative members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, especially Jesse Helms, prevailed.)61 Other Western sources penetrated behind the Iron Curtain, most prominently Deutsche Welle, Vatican Radio, and Radio in the American Sector (RIAS), which broadcast from West Berlin and West Germany. By 1975, the Russian factories had churned out an astounding fifty million shortwave sets, enough for nearly every household in the Soviet Union.

During the Cold War, Western governments and academics conducted surveys of visitors and emigrants from the Communist bloc that demonstrated that they trusted the Voices far more than the domestic media. These data were confirmed after 1991, when researchers gained access to secret internal Russian polls. Listeners were impressed with the speed and accuracy of Western broadcasts, and especially by their willingness to air unfavorable news. A classic example was a Bulgarian-language BBC report of an ink bottle thrown at Prime Minister Thatcher during a visit to West Germany: the story gained widespread currency among Bulgarian listeners, who could not imagine their domestic media reporting such an attack on one of their own leaders.62

The Communist bloc could respond to this barrage of outside broadcasts in one of three ways: by improving its own news coverage, by attempting to modify through diplomatic means the content of Western broadcasts, or by jamming the Voices. At one time or another, it tried all three.

The Soviets did gradually improve the timeliness and accuracy of their reporting, but as the Chernobyl meltdown demonstrated, this improvement was too little, too late.

Likewise, the Russians had little diplomatic leverage with which to tone down the Voices, and even if they could have done so, it would have done them little good, as the Voices derived most of their legitimacy from their evenhandedness. What did the most damage to the credibility of the Soviet Union and its satellites was not so much unfavorable news about them, but rather the glaring contrast in accuracy and promptness between the Voices and the domestic media. The more strident the programming, the less the credibility; among Hungarian listeners, 21 percent found the more hard-edged, CIA-funded RFE unreliable, versus only 4 percent for the VOA and 2 percent for the BBC.63

That left jamming the broadcasts, a measure to which the Soviets and Eastern Europeans devoted vast resources. The Soviets started interfering with the Voice of America almost as soon as it initiated its Russian-language service in 1947. Then they began jamming the other Voices as well. By 1958, the Russians were expending more resources on jamming than on their own domestic and foreign broadcasts. A report to the Central Committee dryly noted that while at any one time about 50 or 60 Voices stations were broadcasting to Russia, they were answered by 1,660 jamming stations with a total power output of over fifteen megawatts. (Ironically, history’s first known jamming was aimed by the Nazis against Soviet war broadcasts. The Soviets’ reports of the adulterous affairs of the Third Reich’s leaders especially irked the Nazi hierarchy.)

Complete blocking of all the Voices’ broadcasts proved impossible. As with any long-distance shortwave radio broadcast, jamming was accomplished with a sky wave bounced off the ionosphere; this method did cover a very wide area, but it was also spotty and relatively ineffective. Sky-wave jamming also suffered from “twilight immunity”: late in the afternoon, broadcast signals of certain frequencies from the west, which was still in daylight, were bounced back to earth from the ionosphere, but the jamming signals in the east, transmitted in darkness, penetrated through the ionosphere, and thus allowed for an approximately two-hour period around sunset of relatively clear reception. Jammers also used a direct, line-of-sight ground wave; this was highly effective, but only over a small area.

In practice, the Soviets broadcast sky-wave jamming signals over the entire country, and ground-wave signals over urban areas, and even in the local rural areas where the more better-connected intelligentsia had their dachas.

The Soviets and their allies succeeded only in making radio reception of the Voices challenging enough to increase their appeal as forbidden fruit. The Voices could still be heard by several different techniques: listening at just the right time of day, changing channels every few minutes, or carrying a receiver into the countryside.64 In the early 1950s, during the most intense period of jamming, researchers estimated that between 5 and 12 percent of broadcasts could be heard—just enough to increase the allure of tuning in and the perceived value of the programs that got through, but not enough to discourage citizens in the Eastern bloc from trying.

Of Soviet visitors to the 1958 Brussels World Fair—admittedly an elite, but also a loyal, communist group—92 percent admitted listening to the Voices. When Boris Pasternak, who had been made an unperson when he received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1958, died in 1961, thousands of Russians, who had heard of his death from the BBC, streamed into the small writers’ village of Peredelkino, where he had a dacha, to attend his funeral.65

Research by the KGB showed that the BBC and VOA could be heard even at certain locations in Moscow, Kiev, and Leningrad. The KGB report also lamented the massive production of shortwave receivers: “It is enough to point out that at present, up to 85 percent of shortwave receivers are located in the European part of the USSR, where our own shortwave broadcasts cannot be heard and where it is possible to listen only to hostile radio” (italics added). By the 1970s, the Voices could be easily heard throughout even the largest Russian cities.66

As if that were not enough, only 15 percent of German sets, and a minuscule 0.1 percent of American radio receivers, were equipped to receive Soviet shortwave broadcasts.67 (The author’s parents owned one of these rare American sets, which provided him with the occasional thrill of distant reception and reliable amusement at the constant stream of turgid Marxist rhetoric.)

The ebb and flow between Russian reformers and hard-liners and United States–Soviet Union relations dictated the intensity of jamming. Khrushchev dialed it down during his rule, only to temporarily ratchet it back up in May 1960 when Soviet missiles downed a U-2 spy plane. After that year, the Soviets again reduced jamming, and in particular allowed broadcasts when they wished their public to receive certain news that was too sensitive for domestic stations. For example, the Soviet Union did not report its own atmospheric nuclear tests, but intentionally allowed its citizens to hear about them from the Voices. Likewise, the Soviets despised the East Germans, but could not directly attack them in their own media; when the Voices broadcast news that reflected poorly on East Germany, the Soviets stopped jamming.

In June 1963, John Kennedy gave his famous American University speech calling for a de-escalation of the Cold War, after which all jamming ceased. At the same time, in an effort to compete with the Voices, the Soviets revamped their media, most notably with a round-the-clock news station, Mayak, and a few years later with increased television production and a lively TV news program, Vremya (“Time”), modeled on Western news shows.68

The Soviet Union’s most bizarre competitive effort soon followed. By 1966 it had become apparent that radio and television had rendered the agitator obsolete. Rather than let the institution wither and die, the Soviets layered on top of it a new, improved version, the “politinformators”: literate, well-educated performers, under the direct supervision of party organs. They were specifically tasked with counteracting the Voices’ influence. At least a million were “trained,” but more often than not, workers perceived them as stooges of Central Committees, and their performances at meetings often consisted of verbatim readings from party newspapers. Soon, they became a laughingstock. Like the agitator, however, the politinformator persisted almost until the fall of the Soviet Union.69 The Soviets calculated that livelier radio and TV broadcasting and politinformators would compete successfully with Western media. Instead, they set in motion a series of events that fatally crippled their credibility and, ultimately, communist rule in Europe.

In early 1964—months before Khrushchev’s fall from power—the Soviet hard-liners fired the “opening shot” in their campaign against dissident literature with the trial of poet Joseph Brodsky. His work was both lyrical and entirely nonpolitical, and his trial was a Kafkaesque witch hunt famous for this exchange between the judge and the defendant:

Judge: And what is your real trade?

Brodsky: I’m a poet and a translator of poetry.

Judge: Who has recognized you as a poet? Who has given you a place among the poets?

Brodsky: No one. And who gave me a place among the human race?

Judge: Did you learn that?

Brodsky: What?

Judge: To be poet. You didn’t attempt to go to a university, where people are trained, where they’re taught?

Brodsky: I didn’t think that could be done by training.

Judge: By what, then?

Brodsky: I thought that by God.70

But for the courage and determination of a woman named Frida Vigdorova, Brodsky’s trial would never have come to light, and he might have disappeared into the Gulag without a trace. A small, timid woman, initially so meek and orthodox that she was elected to a regional party committee, she possessed a remarkable moral sense and fought for those she saw as wronged by the system: a battered woman, a family unfairly crammed into a tiny communal apartment, or a schoolboy unfairly smeared by lies. When asked why she helped the boy, she replied simply, “He is a person to me.”

When, in February 1964, Brodsky, whom she did not know, went on trial, she attended. When the judge shouted at her to stop taking notes, Vigdorova replied that she was a journalist and a member of the Writers’ Union. When the judge continued to shout at her, she took notes of that, too. Her transcript eventually found its way abroad, where it was broadcast by the Voices back to the Soviet Union.71 A firestorm of protest from the cream of the Western intelligentsia, including Jean-Paul Sartre, ensued and resulted in Brodsky’s release after eighteen months of hard labor in the Arctic north. In 1972 he was exiled to the West, and in 1987 he received the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Although Vigdorova’s transcript made the Brodsky trial a high-profile event, it had relatively few long-lasting repercussions. At the time the poet was twenty-three years old and almost completely unknown, and the authorities prosecuted him not for the content of his poetry but for “social parasitism,” a catchall Soviet phrase for the avoidance of useful work. The publication and broadcast of the transcript did not occur until after the trial was long over, and so could not provoke protest during the trial itself. Two years later, that would change with the trials of Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel, which set in motion a sequence of trials and protests that destroyed what little remained of the regime’s international and domestic credibility.

Sinyavsky was born in 1925; after serving in the Russian army in World War II, he studied at Moscow University. Like many Soviet citizens of his age, he began his young life as a dedicated communist, but in 1951 his father was arrested by the secret police. Five years later Sinyavsky, like many Russians, was moved to outrage by the revelations of Stalin’s brutality in Khrushchev’s “secret speech.”

His disillusionment impelled him to write; under the pseudonym Abram Tertz, Sinyavsky produced the three works for which he was tried: Lyubimov, a gentle satire of a small-town Soviet demagogue; On Socialist Realism, a stuffy analysis of literary theory; and The Trial Begins, a phantasmagorical account of a tribunal modeled loosely on the Stalinist “Doctors’ Plot,” which was Stalin’s final, paranoid act of persecution—the show trials of Jewish physicians on fabricated charges of conspiracy to kill the Soviet leadership.72

Yuli Daniel, also born in 1925, was Jewish and had served with distinction in the war, after which he was pensioned off because of a combat injury. Whereas Sinyavsky had published in the official media, including Novy Mir, Daniel was far less well known, having been unsuccessful in getting literary exposure in a “legal” venue. However, he did achieve several foreign publications via the samizdat-tamizdat route, under the pseudonym Nikolai Arzhak. One of these, a satire titled This Is Moscow Speaking, involved an official proclamation of “Murder Day,” an eighteen-hour period during which each Soviet citizen was allowed to kill anyone, as long as the victim was not a policeman, a soldier, or an apparatchik. This story so enraged the prosecutors that they decided to try Daniel alongside the better-known Sinyavsky.

The authorities had both men arrested in September 1965, and tried five months later in the Supreme Court of the Russian Republic under the infamous Article 70 of the republic’s code. Under this law, anyone could be prosecuted for “agitation or propaganda with the purpose of subverting or weakening the Soviet regime.” Although the proceedings harked back to Stalin’s show trials, three things about them were different. First, in spite of the authorities’ attempt to pack the court with supporters of the regime, someone in the courtroom, perhaps a relative of one of the accused, had smuggled in a tape recorder, from which a nearly complete transcript was later assembled; second, the defendants pleaded not guilty; and third, unlike Brodsky, the two were tried for the content of their work. Never before had Soviet prosecutors gone after anyone for writing fiction (although to be sure, many writers, such as Mandelstam, had been exiled, imprisoned, and even executed under other pretexts).73 After four days of farcical proceedings, the court duly convicted and sentenced them, Sinyavsky to seven years of “strict regime,” Daniel to five.

Sinyavsky’s and Daniel’s real crime had been to publish their pseudonymous works abroad, and as with Brodsky, it would be from abroad that the blowback came, but with one essential difference: with Sinyavsky and Daniel, the protest came in real time. Almost from the moment of their arrest, their family and friends had tumbled to the fact that they could generate domestic support by conveying information via foreign correspondents to the Voices, which would then broadcast the story of the trial to the Soviet Union. The authorities, who had not fully absorbed that a high percentage of Russians regularly listened to the Voices, were faced with a unique, terrifying scenario: even on the trial’s first day, about fifty supporters, drawn by the foreign radio broadcast coverage, converged on the courtroom. Each evening, Russians tuned into the Voices for news of the trial, and each successive morning, ever-larger crowds consisting of both supporters and foreign reporters assembled. From time to time, both groups would unobtrusively steal away to a local café where the former fed the latter pelmeni—delicious hot dumplings to fight both hunger and the bitter cold—and information.74

Further fireworks were not long in coming from abroad, where the greatest names in literature, respected in Russia in a way few Westerners understood, spoke out against the trial. So as not to alarm the authorities, when Daniel’s wife Larisa visited him in prison, she veiled the strength of foreign support behind this message to her husband: “Grandmother Lillian Hellman asked me to say hello. Uncle Bert Russell also sends his regards. Your nephew, Günter Grass, talks about you a lot, and so does his younger brother, little Norman Mailer.” Observed Daniel’s guard, “It’s nice that you Jewish people have such large families.”75

Even the Western communist parties denounced the proceedings. Complained the leader of the British party, John Gollan, “Justice should not only be done but should be seen to be done. Unfortunately, this cannot be said in the case of this trial.”76

Next came Taubman’s students’ “sharp questioners.” When a professor at Moscow University affixed his name to a letter supporting the convictions, his students asked him whether he had signed under duress. Had he answered yes, they would have forgiven him; when he admitted that he had signed it voluntarily, they walked out of his class. Even the president of the court of the Soviet Union itself (as distinguished from that of the Russian Republic, which held the trial) criticized the tribunal’s conduct.77

Two writers, Alexander Ginzburg and Yuri Galanskov, in their turn compiled The White Book, a samizdat four-hundred-page transcript of the Sinyavsky-Daniel trial proceedings, along with other related documents; in 1967, they and two associates found themselves prosecuted for these. The court sentenced all four to long terms the next year in a proceeding dubbed “The Trial of the Four.” Ginzburg served his time and was later exiled to the United States, but Galanskov died after prison authorities ignored his bleeding ulcers; just before his demise he wrote home, “They are doing everything to hasten my death.”78

The “Trial of the Four” duly attracted its own foreign broadcasts and domestic supporters, one of whom, the young dissident Vladimir Bukovsky, was himself arrested, tried, and sentenced to three years at forced labor for his efforts. Bukovsky, who was actually sentenced before “The Four,” was by that point no stranger to the penal system, having been sent to various psychiatric facilities in 1965 for copying a book by the Yugoslav dissident Milovan Djilas and for demonstrating at the Sinyavsky-Daniel trial. Bukovsky conducted protests and hunger strikes in prison and was delighted when his guards relayed reports of his actions that they had heard a few days later on the BBC or RL.79

Apparently, prison personnel also listened avidly to the Voices. When dissident Andrei Amalrik wound up in the Gulag in the early 1970s, he became deathly ill with a severe ear infection and meningitis. The prison doctor took an instant dislike to Amalrik because of his political crimes and spoke poorly of him to the dispensary staff, who then relayed her comments back to Amalrik. When he confronted the doctor about her unprofessional behavior, she repeated her insults and then shouted at him, “Why does the Voice of America talk about you and not about me?”80