9

If you doubt that the Internet has fundamentally altered the balance of power between the rulers and the ruled, just ask Trent Lott, the former majority leader of the United States Senate. On Thursday, December 5, 2002, Lott uttered this lulu at Strom Thurmond’s hundredth-birthday party:

I want to say this about my state: When Strom Thurmond ran for president [in 1948], we voted for him. We’re proud of it. And if the rest of the country had followed our lead, we wouldn’t have had all these problems over all these years, either.1

Parsing Lott’s tribute didn’t require a doctorate in political science: the nation would have been better off electing a hard-core segregationist president in 1948. The press, though well represented at the festivities, curiously failed to report Lott’s words in any detail. It wasn’t as if Lott had inaudibly mumbled his tribute or that the proceedings had rendered the reporters comatose; according to one attendee, Lott’s remarks elicited “an audible gasp and stunned silence.”2 Rather, the press, perhaps having been co-opted by the hosts, or out of simple social decorum, elected to focus instead on the Marilyn Monroe impersonator who sang an appropriately breathy “Happy Birthday, Mr. President Pro Tempore” and planted a fat kiss on the centenarian’s forehead.

To be fair, the media did not completely ignore Lott’s testimonial: ABC briefly mentioned it in a newscast—at 4:30 AM. The Washington Post buried a small article about it in its back pages, and Gwen Ifill, the wickedly funny African-American host of PBS’s Washington Week, dedicated the show’s occasional “What were they thinking?” feature to the Lott quote.

The twenty-four-hour news cycle turned, and the story disappeared from the mainstream media. Then, something unusual happened; the incident got taken up by bloggers, most prominently Duncan Black (Atrios.blogspot.com), Joshua Marshall (Talkingpointsmemo.com), and Glenn Reynolds (Instapundit.com), all of whom were outraged by Lott’s remarks. Critically, Ed Sebesta, who maintained a database of Confederate nostalgia buffs, pointed out to the bloggers that Lott had a long history of praising southern racism to Confederate enthusiasts. The nation at large was about to find this out.

An online firestorm developed that forced the mainstream press to revisit Lott’s remarks. The senator issued an apology, which only fanned the flames; on December 12, President Bush castigated the majority leader in front of a black audience, and on December 20, Lott quit the leadership post.3

Interestingly, the senator had made a nearly identical speech in 1980 to a southern audience, which, although well reported in the local press, did not get national coverage. What had changed? By 2002, anyone who wanted to become a columnist or journalist could go online and do so. Yes, the members of this “New Press” had, on average, less training, experience, access, and ability than their traditional, professional colleagues. (“Bloggers in pajamas,” sniffed mainstream reporters.) Yet as l’affaire Lott illustrated, the aggregate instincts and efforts of these “amateurs” could put their mainstream colleagues to shame. It would not be the last time this would happen. Black, Marshall, Reynolds, and Sebesta were nothing more and nothing less than the digital age’s direct descendants of Cobbett, Hone, Paine, and Carlile—commentators whose newly acquired access to mass communication technology allowed them to bypass the traditional channels of power and influence.

At its most basic level, the Internet functions as a duplicating machine that allows each user to easily copy documents, images, sound files, and video (and, even more easily, the hyperlinks to them), and to send them to others. This increased personal empowerment is part of the larger story of personal copying and communications technologies discussed in Chapter 8. The photocopier, whose history goes back a century, supplies a superb perspective on the Internet revolution.

A photograph of a document or drawing is essentially a duplicate, albeit an expensive one. In 1911, Eastman Kodak introduced a device that transferred a negative—that is, a white-on-black document image—directly onto photographic paper without intervening film: the famous, and massive, Photostat machine. (If a normal black-on-white image was required, the first copy was itself then copied.)

Although the Photostat automatically performed the complicated imaging and developing processes internally, it required running water and electricity—no small thing in the early twentieth century—and could easily gobble up an entire room.4 The device inhaled enormous quantities of expensive photographic paper and chemicals and spat out thick, foul-smelling duplicates whose curled edges made them the devil to file. It fell to a single-minded patent attorney, Chester Carlson, to devise a photographic process that used plain paper. Carlson’s invention would revolutionize the business world and, a decade later, find itself at the center of a titanic struggle between the United States government and the press.

Carlson was born in 1906 in Seattle, the descendant of four immigrant Swedish grandparents and the son of a brilliant but ne’re-do-well father whose various business failures endowed Chester’s childhood with Dickensian poverty, intense loneliness, and prodigious self-reliance.

When he was four, his father, lured by stories of fertile land and plentiful, cheap labor, took the family to rural Mexico. When fending off scorpions, snakes, and bandits did not consume the family, rescuing cows and chickens from the thick, viscous mud that surrounded their farmhouse did. After they had returned to the United States, Chester’s chronically ill mother worked as a housekeeper for a physician who took pity on the family and put them up in a tiny single back room.

The family next moved to the rural town of Crestline in southern California, where young Chester for the first time reveled in the company of his peers. The next Christmas, the dam project that employed most of the town’s men closed, and Carlson found himself once again nearly alone, with only his teacher for company: “Sometimes I’d look inside, and there was the teacher at her desk, her chin in her hand, staring at the wall.”5

Carlson somehow made it through a local college and then Caltech, just in time for the Great Depression. Upon graduation he worked briefly as an engineer at Bell Labs before the downturn vaporized his position. He next found employment as a clerk at a patent law firm; in order to advance his career, he obtained a night school law degree.

Although he prospered as a patent attorney, inventing stirred his heart. From an early age, he had been entranced by printing and copying apparatus, and his harsh, solitary childhood had imparted to him a profound independence of thought and action. In those days a patent attorney spent many hours, and even days, waiting for bulky, expensive document copies; surely, he thought, there had to be a simpler way of printing them on plain paper.

Had Marconi not transmitted wireless signals over great distances, someone else would soon have done so; the same was also true of paper manufacture, the printing press and all of its subsequent refinements, and nearly all of the other communications advances discussed between these covers. All of these inventions, wonderful as they were, depended on well-established physical principles and evolved from similar preexisting technologies. By contrast, the process that Carlson developed represented such a radical departure from previous duplicating and copying methods and rested on such arcane scientific principles that had he not spent the greater part of his adult life pursuing photocopying, it might never have seen light of day.

At some point, he came across a report by a Hungarian physicist, Paul Selenyi, who had used an ion beam to lay down a pattern of electrical charges on a rotating drum. An expensive, cumbersome ion beam was out of the question for office use, but Carlson’s scientific training had also made him aware of Albert Einstein’s photoelectric effect, whereby light rays induce an electrical charge in certain substances.

Selenyi had not thought to use light, but that was close enough for Carlson, who realized that he just might be able to apply Einstein’s photoelectric discovery to produce the same effect with a camera lens, and then convert the drum’s electrical pattern into an ink image on plain paper. Over the next quarter century, starting in primitive home laboratories and progressing to ever better-equipped, better-staffed, and better-funded facilities, he did just that. Eventually, he produced a working device for the Haloid Company, whose primary business was photographic paper. Haloid changed its name in 1958 to Haloid Xerox, and in 1961, to Xerox.

In 1959, the company produced its first practicable model, the 914, which took the business world by storm. Contemporary accounts of the 914’s introduction exude an almost millennial flavor: the machine transformed copying, previously a laborious, repugnant activity, into a pleasant task accomplished with the push of a button.

The 914 had just one drawback: its overuse by office workers hypnotized by its capabilities. As put by author David Owen, “Invention was the mother of necessity.” In other words, the new machines seemed to create their own demand out of thin air: they ejected blackboards from conference rooms and replaced them with stacks of copied notes and drawings. The venerable routing slip, attached to an original document, which in one form or another had meandered from desk to desk for centuries, disappeared in favor of mass-copied memos. Five years before the 914’s invention, the old photographic machines turned out just twenty million pages annually worldwide; five years after it, Carlson’s devices cranked out nearly ten billion copies per year. Almost instantly, the 914 consigned an entire generation of office mainstays—Kodak’s Verifax and 3M’s Thermofax photocopiers—to landfills.

Ironically, tiny Haloid/Xerox initially found no partners for this business venture; in the absence of support from a larger company, the project became a risky, bet-the-company gamble, and its unaided success vaulted it into the front rank of global commerce. Mighty IBM, for example, turned Haloid down because the computer giant did not see a big enough market for the product. Had IBM’s forward vision been more acute, the verb “xerox” would not today enrich the English language and inflate Scrabble scores.

The story of Carlson’s invention was unusual for another reason; it ended happily for the inventor, as the 914’s royalty of one-sixteenth cent per page made him wealthy beyond counting. The money did not greatly affect his lifestyle. On European trips, his wife had to prevent him from buying third-class train tickets, and he gave almost all of his fortune away before he died in 1968.6

Only one other photographic copying technique survived the Xerox machine more or less intact: microfilm. Almost as soon as Louis Daguerre demonstrated his camera and pictures in 1839 to the French Academy of Sciences, inventors realized that vast amounts of information could be photographically miniaturized onto a tiny amount of film. Reginald Fessenden, the radio engineer encountered a few chapters ago, calculated that the technique could fit 150 million words onto a one-inch film square. By 1935, Eastman Kodak had perfected the now familiar sixteen- and thirty-five-millimeter rolls still used in libraries and archives today. Microfilm, as we saw in Chapter 8, also became the medium of choice for smuggling military secrets and seditious literature across borders.

The Soviet Union, unsurprisingly, considered Carlson’s invention useful but dangerous, and so restricted its use to the planning elite. The Russian version of the Xerox, the Era machine, was available only at state facilities. All copies were logged, and misuse often resulted in jail time; few but the bravest Russians commandeered these devices for nighttime samizdat work.7 Only in Poland, with its advanced dissident technology and infrastructure, did photocopying play a significant role in the downfall of communism. Rather, it would be in the West that the Xerox machine proved most subversive.

Even at Harvard, few had seen the likes of Daniel Ellsberg. The son of Jewish converts to Christian Science, he graduated third in the class of 1952 with a summa cum-laude degree in economics.8 His senior thesis was published in the prestigious American Economic Review and so impressed two giants in the field, Wassily Leontief and Carl Kaysen, that they offered him a junior fellowship at the school. Harvard reserved these three-year appointments, whose only formal obligation was attendance at a posh weekly dinner party, for those too brilliant to be confined to a run-of-the-mill doctoral program. The university almost never gave them to newly minted graduates.

Initially, Ellsberg refused the fellowship and instead went to England for graduate work at Cambridge, followed by a successful stint as a Marine Corps lieutenant; disappointed at not serving in combat during his initial enlistment, he re-upped for an extra year in the vain hope that the Suez crisis of 1956 would draw in American forces. Over the next dozen years, he bounced among the RAND Corporation, where he applied his theoretical expertise to nuclear deterrence; the State and Defense departments; and Harvard, where he earned a PhD. His dissertation described the “Ellsberg paradox,” which became a game theory staple.

In 1965, the State Department sent him to Vietnam, where he found himself under the command of Paul Vann, the risk-loving officer whom New York Times reporter Neil Sheehan would later make famous in A Bright and Shining Lie. Always a true believer, Ellsberg fashioned himself into a fierce Vietnam hawk. Over the next two years, he sought out the combat experience he had missed in the peacetime marines and regularly accompanied army patrols, often in the point position, the most likely to draw enemy fire. It did not please the local American officers to have an ex-marine with no combat experience tagging along in the rice paddies; it pleased them even less when he launched into lectures on the finer points of infantry tactics.

Ellsberg’s experience in the military and political quagmires of the Vietnam conflict convinced him that the war was unwinnable. He was not the only American official who reached that conclusion: so did many in the Defense Department, starting with Secretary McNamara, who ordered a task force, under the direction of a subordinate, Leslie Gelb, to turn out a detailed examination of the war.

By 1969, the task force, which Ellsberg was peripherally involved in, completed its job; its report ran to forty-seven volumes—seven thousand pages. The published report, The Office of the Secretary of Defense Vietnam Task Force Study, would later become popularly known as the Pentagon Papers. It documented, often in painful detail, the brutality, lies, failures, and deceits of American policy in Indochina under four presidents. McNamara, wracked with guilt over the war, intended the project for future historians. By that point, Ellsberg had moved back to RAND’s headquarters in Santa Monica; locked in his black four-drawer top-secret safe rested one of the few copies of the explosive report. (Since the standard RAND file cabinet was gray, a black one was a highly visible status symbol.)

He decided to blow the lid off the top-secret report. As he analyzed the task,

[The Papers] would have to be copied. I couldn’t do that at RAND or at a copy shop. Maybe it was possible to lease a machine. I got out of bed and picked up the phone in my living room and called a close friend, my former RAND colleague Tony Russo. I said there was something I would like to discuss with him. I’d be over shortly.9

Ellsberg asked if Russo could get hold of a Xerox machine. Indeed he could; Russo’s girlfriend Lynda Sinay owned an advertising company that leased one, and she agreed to let Ellsberg use it after hours. On the evening of October 1, 1969, after most RAND employees had gone home, Ellsberg opened his black safe, filled his briefcase with the highest-priority sections, and headed out the front door. The RAND guards paid him no attention.

Sinay had leased a 914—by today’s standards, cumbersome and slow. Even with the help of Sinay and Russo, copying just a single briefcase load of documents took all night. Beyond the logistic difficulties of clandestinely copying the documents, he also exposed his friends to prosecution. He involved his thirteen-year-old son Robert in the copying, and at one point, even his ten-year-old daughter Mary. Prosecutors would indict Russo with him, while Sinay sweated out her status as an unindicted coconspirator.

Ellsberg sent his first batch of copies to Senator Fulbright, who, although initially enthusiastic about making them public, soon demurred because of their top-secret classification. The same sequence of events played out with Senator George McGovern. Their refusal dealt a serious blow to Ellsberg’s hope of avoiding questioning, because the Constitution shields members of the Senate from interrogation on subjects discussed in the chamber; therefore Ellsberg could have remained anonymous.

Their refusals forced Ellsberg to go to the press. In March 1971, he brazenly walked into a copy shop in Harvard Square and ran off more photocopies on a high-speed machine for Neil Sheehan at The New York Times.10 After three months of researching, cross-checking, legal advice, and agonizing, the Times published the Pentagon Papers, piece by piece. The Washington Post and fifteen other publications followed. Although the government initially obtained injunctions against the newspapers, two weeks later the U.S. Supreme Court vacated the rulings, and in 1973, a federal court dismissed all charges against Russo and Ellsberg.11

For a half century after the 914’s appearance in 1959, xerographic copiers constituted a halfway point in the empowerment of individuals by modern personal communications technology; for the first time, ordinary people could copy thousands of pages of written material. As explained in the introduction, because W. E. B. Du Bois did not have duplicating equipment, hundreds of thousands of black Americans suffered a form of slavery for decades after the government suppressed his explosive report on the subject; because Daniel Ellsberg did have duplicating equipment, he hastened the end of the Vietnam conflict. Were that not enough, Ellsberg also set into motion the events that would force the resignation of Richard Nixon. The president, upset at the release of the Pentagon Papers, authorized the burglary of the office of Dr. Lewis Fielding, Ellsberg’s psychiatrist. This episode, so-called “Watergate West,” provided not only the legal grounds for dismissing Ellsberg’s prosecution but also a key clue that traced responsibility for the original Watergate break-in by E. Howard Hunt and Gordon Liddy back to the Oval Office.12

Yet copying the Pentagon Papers was anything but easy, and their public dissemination still depended upon broadcast stations and printing presses, operated by a privileged few, who themselves would soon face the full wrath of the government. Twenty-one months separated Ellsberg’s first trip to Lynda Sinay’s office from The New York Times’ publication of the Pentagon Papers. During that interim, Ellsberg spent many thousands of dollars—real money in those days—worked long days and nights, and exposed both himself and others to legal peril in order to make copies that he could then not immediately disseminate. Over the next few decades, dramatic advances in digital technology would erase these barriers.

Around the time that Harvard awarded Ellsberg his PhD, a computer scientist at MIT, J. C. R. Licklider, suggested the possibility of a globally linked “Intergalactic Computer Network.” The Defense Department, intrigued at the prospect of a decentralized communications system that might survive a nuclear conflict, appointed Licklider the first director of computer research at its Advanced Research Projects Agency (known at various times as either ARPA or DARPA). There, he and his successors brought his concept to fruition with the ARPANET, the Internet’s forefather.

Prior to the Internet, all mid-twentieth-century electronic communications technologies shared an essential drawback: their linkages were “circuit switched,” meaning that the two terminals of any connection were linked by a single, and usually temporary, channel. In that era, the pathway between two telephones typically proceeded through multiple relays; that pathway could conduct, even with the most advanced encoding technology, only a handful of calls at a time. ARPA’s scientists realized that a network of any size, let alone a worldwide one, could not function in this manner; for example, an integral network of just one hundred computers requires 4,950 separate direct connections among them.13

In order to get around this limitation, Licklider and his colleagues devised a “packet switching” technology that broke messages and data into multiple pieces, individually labeled them, and sent them on their way along different paths to their final destination, where they were put tidily back together.

The old circuit-switching method can be thought of as a child’s tin-can-and-string telephone, able to link only two terminals with a single, dedicated connection; packet switching can be imagined as a disjointed moving company that sends the drawers and body of a bedroom dresser on separate vehicles taking different routes to its ultimate destination, where the dresser is reassembled.

By the late 1960s, researchers had made packet switching a reality, and in 1969 a team at UCLA fired up the ARPANET’s first active site, or “node.” Before that year ended, ARPA scientists added three more nodes, and in 1972, the first e-mail traveled over the new network. By the early 1980s, ARPANET connected most of the world’s major research facilities. This new network, variously called the “information superhighway” or “infobahn,” began to excite the popular imagination, but it was still far from being a mass-market tool.14

This soon changed. Just as Gutenberg wasn’t trained as a printer and the young Thomas Edison knew nothing about sound reproduction or lighting, Tim Berners-Lee, a computer scientist at CERN, the huge European high-energy physics research center, wasn’t a networking specialist. In 1990, he had a more immediate problem: connecting the facility’s myriad computers.

CERN straddles the French/Swiss border and is home to thousands of scientists and staff. The facility also hosts an even larger number of visiting academics who spend days, weeks, or months running their experiments on CERN’s massive particle accelerator. Most of them brought along their own computers, which in the 1980s constituted a diverse collection of mainframe machines and, increasingly, the newfangled small personal computers popping up in offices and homes. Earlier, in 1989, Berners-Lee wrote a now famous proposal that asked, “How will we ever keep track of such a large project?”15 To a computer scientist like Berners-Lee, the answer was obvious: to somehow link up all these computers, with their variegated hardware and operating systems, so that information on one system was available to all the others.

Berners-Lee conceived of a “Web browser,” a software program that employed links within documents—so-called hypertext—to retrieve files from distant systems. It turned out that an English company, Owl Ltd., had created a program named Guide that linked documents in this manner, but only within a single computer; it could not retrieve pages from other computers. A similar program, HyperCard, which had been invented in 1987 and subsequently bundled into Macintosh computers, had caught the eye of Berners-Lee’s colleague Robert Cailliau.16

In Berners-Lee’s words,

The version now commercialized by Owl looked astonishingly like what I had envisioned for a Web browser—the program that would open and display documents, and preferably let people edit them, too. All that was missing was the Internet. They’ve already done the difficult bit!17

Berners-Lee finished the job that Guide and Hypercard had begun by writing the now familiar Web software routines: a Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) to encode documents, the Universal Resource Identifier (URI, now URL) for addressing them, the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) to send them on their way, and the code that drives the Web’s ultimate information repositories, the servers. He credited much of his success to the sophistication and ease of use of his NeXT computer, a machine designed by Steven Jobs after Apple ousted him in 1985.

Like David Sarnoff, who had been consumed by the chicken-and-egg question—Who will buy radio music boxes if no broadcasting stations air programs, and who will build broadcasting stations if no one owns radio music boxes?—Berners-Lee was vexed by a similar concern: “Who would bother to install a [browser] if there wasn’t exciting information already on the Web?”18 To succeed, he would have to broaden his horizon beyond CERN.

In late 1991, Berners-Lee and Cailliau traveled to a hypertext software conclave in San Antonio to demonstrate their new browser. The meeting site did not have an Internet connection—in those days, almost none existed outside major research and government centers. To demonstrate their software, the two planned to call up their CERN server with a Swiss-made telephone modem and a scrounged dial-up account. One small problem remained: their modem, a European-standard 220-volt device, could not use American 110-volt current, so they had to disassemble it and solder in a connection to a voltage transformer.

The demonstration succeeded beyond their wildest dreams; when they returned to the conference two years later, almost all of the exhibits were Web-related.19 In 1993, Mosaic, the first browser that could be easily installed and used by non-geeks, appeared, followed by Netscape Navigator in 1994 and Internet Explorer in 1995; by the end of that year, Berners-Lee’s creation connected sixteen million users worldwide, or 0.4 percent of the earth’s population; by mid-2011, it connected 2.1 billion people, or 30 percent.20

Although by 1999 increasing numbers of Americans had Internet access, it still remained largely a one-way medium. Posting information online was in many ways more difficult than submitting a document to a commercial printing company. First, the user converted the text or word processor document into Hypertext Markup Language (HTML). Next, although HTML had been designed to produce screen-ready pages, most users found that they needed to adjust the document code to get a more acceptable and professional appearance. (Documents written on early versions of Microsoft Word, the most commonly used word processor, yielded a particularly unattractive HTML appearance.)

Most challenging of all, the user had to upload the final HTML document and associated files to a Web site—assuming he or she had access to one—with a finicky File Transfer Protocol (FTP) program onto an even more finicky server. This sequence was, with some perseverance, doable, and with trial and error, it soon became routine, but before 1999, only a small percentage of ordinary people were motivated enough to surmount its hurdles.

In that year, a young man named Evan Williams conquered these difficulties. Like Berners-Lee, he harbored no grand ambition to alter the nature and tempo of human communication; he just wanted to make a living.

A mediocre student who grew up on a farm, Williams dropped out of the University of Nebraska in the mid-1990s and hitched his wagon to an Internet boom that soon went bust. His luck did not change:

I had no business running a company at that time because I hadn’t worked at a real company. I didn’t know how to deal with people, I lacked focus, and I had no discipline. I’d start new projects without finishing old ones, and I didn’t keep track of money. I lost a lot of it, including what my father had invested, and I ended up owing the I.R.S. because I hadn’t paid payroll taxes. I made a lot of employees mad.21

In the late 1990s, he cofounded Pyra Labs, which produced project management software. As part of that effort, the company created an internal software tool for quickly uploading short documents that he called “Web logs,” first onto the company’s internal Web site, and then onto the Internet. Williams called the tool Blogger, and it quickly became more popular than the company’s original products, so he created another company, Blogger.com, to market the new software.22

Before Blogger, services such as Usenet and Geocities allowed contributors to post articles, but they never caught on among the general population. This may have been for aesthetic and technical reasons, or simply because at that time such a relatively small percent of the population was connected that Usenet and Geocities could not achieve “critical mass,” or because of slow dial-up speeds available to most users at the time.23

Just as Gutenberg’s triumph depended on cheap paper, advanced metallurgy, and word spacing, Blogger could not have succeeded without Berners-Lee’s browser and inexpensive, always-on broadband. By 2003, when Williams sold Blogger to Google, the time was ripe for his venture. The browser, Blogger, and broadband, combined with the Web giant’s resources, made uploading as easy as typing the text and pushing the send key; within minutes any grandparent or elementary school student could create and post a professional-looking page.

Almost by accident, Williams had completed the job begun by Johannes Gutenberg five-and-a-half centuries before. At a stroke, everyone was a reporter, a news photographer, a columnist, and a publisher, able to turn out a nearly infinite number of copies at a price indistinguishable from zero. Even more crucially, Blogger allowed people to connect and cooperate in ways never before possible.

The ocean of data that is the Internet flows both ways; “Googling” makes it possible to access knowledge about almost any subject and makes the bibliographic universe instantaneously available. Someone with even a modicum of research skills and access to an academic, government, or nonprofit database can plumb almost any topic to astonishing depth without, well, getting out of his or her pajamas.

The new technology also made experts much more accessible to the public. While the Web did not make Stephen Pinker, Jared Diamond, or Stephen Hawking more likely to answer casual inquiries about psychology, evolutionary biology, or astrophysics, almost anyone who needs help from a less well-known authority now has a reasonable probability of getting it. Several years ago, in the course of writing A Splendid Exchange, I delved into subjects as varied as the course of the Black Death in Asia and the history of refrigeration technology. I found, to my delight, that a polite e-mail to the world experts in these areas (there aren’t many) usually elicited a helpful and encouraging reply.

If Blogger was all Evan Williams had invented, he would have been well enough remembered, but he was just getting started. The 2003 buyout of Blogger made him a Google employee, and this did not suit him. In 2004, he cofounded Odeo, a podcasting company. Because of competition from Apple’s iTunes, his new company did not flourish, but once again, he and his colleagues at Odeo struck serendipitous gold with another incidental internal tool: Twitter.

It’s easy to make fun of this 140-character medium. No one wishes Britney Spears’ self-absorbed, fractured syntax on his worst enemy, let alone what movie the occupant of the neighboring cubicle saw last night. (Or even, for that matter, this one from Evan Williams: “Having homemade Japanese dinner on the patio on an unusually moderate SF evening. Lovely.”)24

But on July 23, 2011, hundreds of millions of people around the world, particularly in China, badly wanted to know precisely what happened when a lightning-induced high-speed train collision in Zhejiang Province tossed passenger cars off a viaduct and killed dozens.

China’s government certainly did not want the public to find out. It acted vigorously to contain the looming public relations disaster for the country’s new bullet train system, the prestigious centerpiece of its national development plans and, until the accident, a potential major source of export revenue. An initial government press release read, “China’s high-speed train is advanced and qualified. We have confidence in it.” Governmental officials directed the press to focus on the human tragedy, and to stay away from the cause: “Do not question. Do not elaborate. Do not associate.”25

Alas, China’s Twitter-like service, Sina Weibo, which has over three hundred million users, shredded the government spin. Just minutes after the accident, a survivor tweeted for help, and the message got forwarded 112,000 times in a matter of hours. The nation’s newspapers could no longer ignore the collision’s subtext without looking foolish. Corruption, cost overruns, and inattention to safety standards had plagued the train system for years. Lamented one propaganda official, “New media triumphed over traditional media. Private media beat public media.”26

Evan Williams had done it again: not only was everyone a publisher and a reporter, but from that moment on, the increasing ubiquity of camera-equipped smart phones relentlessly lowered toward zero the probability that any newsworthy event would go untweeted, unphotographed, or unrecorded. Twitter had become the modern Argus—all-seeing, all-knowing, unblinking, and ever-present. When a 5.8-magnitude earthquake struck northern Virginia on August 23, 2011, tweets sent from near the temblor’s epicenter arrived in New York City before its shock waves.27

Across the globe, in liberal democracies and even in the world’s most repressive states, the new high-access, two-way media provides citizens with a faster, and at times even more accurate, picture of both public and private events than ever before. Despite the obvious distortions and inaccuracies of much material uploaded to the Web, in the middle and long term it sifts and winnows information reasonably well.

Before the printing press, very few titles got published: the Bible, indulgences, the ancient classics, calendars, and so forth; scriptoria did not need to employ acquisitions editors. After Gutenberg, the range of available titles expanded into areas that appealed to the elite, and to the newly literate masses: novels, minor classics, and, of course, erotica. As the supply of available literature swelled, large, established publishers filtered and vetted what they printed.

The Web has similarly exploded outward the range of what is published, and again the same cries of how a new medium has debased standards ring: when any person can publish, anything, no matter how awful, will be published. And yet the Web is highly self-corrective, as its signature tool, Google, demonstrates.

Google’s origins nicely explain how the Web sifts and winnows. The company emerged from the doctoral dissertation of one of its founders, Larry Page, a Stanford computer science graduate student. He settled on a bibliometric analysis of the Internet—that is, the pattern of how pages were linked through hypertext.

In the mid-1990s, when Page came to Stanford, the Internet already contained a vast amount of useful information; the problem was finding it. Consequently, some of the hottest dot-coms were search engine companies, which went public in dizzying succession: Lycos, Magellan, HotBot, and Excite, among many others. (The failure of nearly all of the 1990s dot-coms was similar, in more ways than one, to the post-Gutenberg glut of poorly capitalized printing shops, particularly in Venice.)

More often than not, search results from these sites hid relevant Web pages under a vast heap of useless ones; this author recalls having to sift through links to recipes, porn sites, and product reviews to find useful returns for the term “portfolio theory.” Most famously, perhaps, entering the name of one of the early search engines, Inktomi, into its own site yielded no results.28

Page’s first step, following forward the progress of Web citations, was trivial: he simply inspected the links in each page. The reverse process, determining what pages linked back to a given page, was anything but easy. Page devised an algorithm for tracing these backward links, which he nicknamed BackRub.

Once that was accomplished, an even greater difficulty arose: not all links are created equal. A link from a Web page that itself was cited by a large number of other Web pages—say a seminal paper by an established expert—carries considerably more weight than one from an elementary school civics report. So Page devised another algorithm (named PageRank, after himself, of course) to compute a page’s importance.

It soon became apparent to Page and his collaborator, Sergey Brin, that they were chasing a rapidly accelerating greyhound. The Web already had about ten million pages, with perhaps one hundred million links among them, and both pages and links were at that point growing twentyfold per year.

To their delight, Page and Brin found that their algorithms accurately identified the most authoritative and relevant pages on the Web. Work by highly regarded academic, government, and industry sources, for instance, reliably outranked the pages of fifth-graders and cranks, something that the Web’s first search engines, such as AltaVista and Excite, notoriously did not do.

Page and Brin had caught their greyhound, and it dragged them forward at a fearsome pace. Because of the Web’s explosive growth, BackRub grew to consume nearly half of the bandwidth of Stanford University, one of the world’s most connected institutions. It was time for Page and Brin either to abandon the project or to deliver it from its academic womb into the wide world of commerce. The two could not have chosen a better environment to do the latter, for nearly all of Stanford’s computer science faculty had at some point either founded a company or at least advised a start-up. The rest, as they say, is history.

The average reader of this book probably uses Google several times per day with the expectation that, in the overwhelming majority of cases, the company’s search algorithm will float the best, most informative hits to the top of the list (just below the highlighted advertisements that generate the company’s massive earnings), and sink the nutcases, preadolescent blogs, and virus-infested Russian sites to the bottom.29

The pedophilia scandal that has enveloped the Catholic Church over the past decade provides a perfect example of the Web’s efficiency. Tragically, priests have habitually abused children sexually almost since the birth of the Church, though, in fairness, many accusations may have been politically motivated.30

In 1871, the hierarchy excommunicated an Australian nun, Mary MacKillop, for reporting the sexual abuse of children by Father Ambrose Keating. (She later became the only Australian saint.) In 1947, a Catholic cleric, Gerald Fitzgerald, founded the Congregation of the Servants of the Paraclete, a hostel in rural New Mexico dedicated to his brethren who had fallen on hard times or strayed from the straight and narrow. As a matter of course, the hostel received significant numbers of priests caught sexually abusing children. Fitzgerald soon realized that his pedophiles were incurable, and he recommended to the hierarchy that they be expelled from the priesthood. For decades, the Vatican routinely ignored Fitzgerald’s reports, and his concerns languished both inside and outside the Church.31

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, local U.S. papers occasionally broke stories about sexually predatory clergymen, but these reports failed to achieve critical mass with a national audience. In 1992, prosecutors accused a Catholic priest, James Porter, of abusing scores of children in and around Boston, a story the Boston Globe covered extensively. The local bishop responsible for Porter, Bernard Law, failed to act, and actually took to the pulpit and called for divine retribution against the Globe. The story did not reach the nation’s consciousness, in spite of the fact that the Globe ran more than fifty articles on the subject.

Fast-forward ten years: in 2002, the Globe ran a nearly identical story about another sexually errant local priest, John Geoghan, whose crimes spanned decades. This time, the public outcry was widespread and loud; local Catholics reacted to the hierarchy’s inattention to the situation with a group called the Voice of the Faithful (VOTF), which spread like wildfire. Within a year, the new organization gained over thirty thousand members in a score of nations. Bernard Law, by now elevated to cardinal, decreed that they could not meet on church property, that their meetings had to be overseen by a priest, and, astonishingly, that VOTF chapters from different parishes could not communicate with each other. Catholics around the world were outraged. The Vatican could not ignore this new amalgamation of laity, and at the end of 2002, Law flew to Rome and tendered his resignation.

What had changed between the Porter and Geoghan episodes? As communications academic Clay Shirky points out, before the Web, individuals could not easily spread a story nationwide. When the Porter scandal broke in 1992, Berners-Lee had barely gotten his Web invention off the ground. Assume that a woman who read the Boston Globe had a cousin in San Francisco who had suffered abuse by a priest, and the Boston resident wanted to inform her San Francisco cousin about the Geoghan story. She would need to phone him or clip, copy, and mail him the newspaper story, and she would need to do the same for each and every additional person she wanted to contact.

By 2002, the Web had revolutionized the process. First, the Globe was now truly global, as it had not been a decade earlier. Former altar boys the world over could read the story. Second, instead of clipping, copying, or calling, the reader could almost instantly forward the piece’s Web page to dozens of friends or, with subsequent generations of forwards, thousands or millions of other people. In 1992, the transmission chain for a news story was limited to local readers who could forward only a few copies at a time. In 2002, several cycles of e-mail forwards could reach a significant fraction of the population of an entire nation or, in extraordinary circumstances, of the entire globe.32

To be sure, the Web did not render the old mainstream media obsolete, for many readers still preferred these traditional outlets, but it did force the newspapers and networks, however grudgingly, to realize that they could not completely control what gets reported, and to whom and where it gets reported. The superiority of the new media in disseminating information, compared with the limited scope of the old media, was well expressed by the late journalist William Safire:

For years I used to drive up Massachusetts Avenue past the vice president’s house and would notice a lonely, determined guy across the street holding a sign claiming he’d been sodomized by a priest. Must be a nut, I figured—and thereby ignored a clue to the biggest religious scandal of the century.33

The dramatic arrival of WikiLeaks highlights the nature and power of this New Press. The first massive WikiLeaks “dump” of United States government documents regarding Afghanistan, in mid-2010, included 75,000 items; later that year, WikiLeaks published 400,000 State Department documents. Few conventional news organizations can muster the manpower to digest that volume of information, but tens of thousands of interested Web surfers, most contributing just a few hours of effort, did.

Newspapers did publish the most important of these documents; critically, they have learned how to partner with the Internet browsing public, “the people formerly known as the audience,” in the words of NYU journalism professor Jay Rosen.34

The Duke Cunningham scandal provided one of the first demonstrations of this new public analytical capacity, as well as its symbiosis with the older mainstream media. For years, the California congressman and famous Vietnam naval aviation ace had taken bribes from a defense contractor, Mitchell Wade. The largest transaction involved the sale of Cunningham’s Del Mar Heights home to Wade’s company at a grossly inflated price. In 2005, a team of reporters at the San Diego Union-Tribune led by Marcus Stern broke the story. In their book, The Wrong Stuff, they noted, “In another era, the story might have gone unnoticed outside [Cunningham’s] home county.” But in 2005, it went viral. Bloggers, including the aforementioned Joshua Marshall of Talkingpointsmemo.com, brought the episode to national attention:

All over the country, people used the Internet to search out and pore over relevant campaign finance reports and property records. The electronic pack would dig out other lawmakers who had benefited from Wade’s campaign contributions. Realtors, real estate appraisers, and even Cunningham’s neighbors began emailing their own assessments of the Del Mar Heights house sale to Stern and other San Diego reporters.35

The most astute news organizations took note of the benefits that this new online investigative partnership with the public offered. One that most definitely did not was London’s Telegraph. In 2009 it broke the story of pervasive, systematic fraudulent expense deductions by members of Parliament (MPs): renovations to boyfriends’ apartments, chocolate Santas, and, in the most memorable case, a £1,645 Queen Anne dollhouse for a duck pond on the property of Sir Peter Viggers, a Conservative MP. (Adding insult to injury, the ducks reportedly disliked the toy cottage.)

Parliament had supplied the Telegraph with two million documents. The disclosure of so much data may well have been intentional; the MPs perhaps thought that the massive data release would buy them precious time during which the scandal could die down or readers might lose interest. After all, what news organization had the resources to crawl through such a mountain of credit card slips, hotel bills, and expense claims forms?

The MPs had probably correctly judged the situation with regard to the old-line media such as the Telegraph, but they badly miscalculated the capability of that paper’s Web-savvy competitors. The Telegraph’s initial coverage had badly scooped its crosstown rival, the Guardian, which then responded by providing its audience with links to a second release of about seven hundred thousand documents. The Guardian invented on the fly and almost out of whole cloth an entire investigative technique, called “computational journalism.” Using sophisticated database software, the paper’s staff scanned and cataloged all seven hundred thousand documents and uploaded them to its Web site for examination by its online audience.

The Guardian encouraged its readers to “Investigate your MP’s expenses.” The paper directed its audience to document index pages for each legislator, complete with mug shots, and instructed them to rate each document on a four-step scale ranging from “not interesting” to “investigate this!” Over 29,000 readers responded, and within days they had buzzed through the massive pile of chits, expense reports, and credit card slips. When the smoke had cleared, six cabinet ministers, thirteen additional MPs, and five peers resigned or did not stand for reelection. Ultimately, six of these miscreants were sentenced to prison terms averaging fifteen months.

The paper had executed a clever human-wave attack on a seemingly insurmountable wall of data. Fortune favors the prepared; for a decade prior to the MP expenses scandal, the Guardian ran one of the world’s most sophisticated online media operations and had won three consecutive Webbies, the award given by the International Academy of Digital Arts and Sciences to the best Internet news site. The paper also occupied the front ranks of the government’s Open Data Initiative.36 While many of the changes wrought by the communications advances detailed in these pages, and the reactions to them, mirrored those from previous eras, here was something truly new under the sun: near-universal access to oceans of material and data.

The episodes involving Lott, Roman Catholic pedophilia, Cunningham, and MP expenses demonstrate three things about the New Press. First, the greater reach of the Internet dictates that more than a few of its members will be able to hold their own against the old, mainstream press with regard to control of information. Second, this corps of writers or bloggers resides, in general, far from places like Washington, D.C., and London, traditional centers of power, and is thus unencumbered by the constraints and social customs in these places: in Arianna Huffington’s words, “truly free of the dependence on access, and the need to play nice with the powers that be.”37 Last, but not least, members of this new corps can connect the dots and communicate with one another in ways never before possible. Here, indeed, was Hayek’s point about widely distributed knowledge suddenly writ large on the Internet: for the first time in history, someone in possession of a unique piece of knowledge can communicate it to the whole world via any combination of three routes: blog it directly, via other bloggers, or use the mainstream traditional media.

As put by Eric Schurenberg, a former editor at Time Inc.,

We all thought we were uniquely qualified to deliver the news because we were trained writers and had access to all the important sources. But what we really had was a printing press, and no one else did. With the arrival of the Internet, we found that lots of other people could write, too, and our readers found they didn’t need us to connect with our sources.38

Those who decry the slow-motion demise of traditional newspapers often cite the resources and bravery of The New York Times during the Pentagon Papers episode. They ask if any of today’s weakened, conglomerate-owned papers would be up to the task. This argument entirely misses the point, for, as previously mentioned, the Internet and social media have largely taken over the essential historical role of the newspapers: the widespread dissemination of information. In the Internet era, Daniel Ellsberg wouldn’t have needed The New York Times.

Today’s Ellsbergs can now copy even the longest documents in seconds, store them in a fingernail-size flash drive (or on a rewritable CD labeled as a Lady Gaga knockoff, as did WikiLeaker Private Bradley Manning), propel them across the planet at the speed of light by the thousands, and upload them to servers to be viewed by millions. The New York Times can still be part of the process, but is no longer its director.

The Web filters and sifts information to a degree not possible with the old array of newspapers and TV networks, which, because of the small number of boots these media place on the ground, simply cannot give all stories the attention and analysis they need. Yes, the Web regularly disseminates spurious and incorrect information, but increasingly used and respected sites such as FactCheck.org gradually eliminate it as well, or at least convert its true believers into targets of general ridicule, such as those who believe that the moon landings were staged or that the CIA engineered the 9/11 attacks.

Mainstream journalists know that bloggers will instantaneously fact-check their pieces, and the more honest reporters will admit that this has made them more careful. The best newspapers benefit from the Web’s fire hose of information and opinion, and particularly from the analytical power distributed among its myriad online participants. The mainstream media, to be sure, still play an important role in the news process, but they have long since lost the ability to say with a straight face, like Walter Cronkite, “That’s the way it is.”

But isn’t the Web an echo chamber of wingnuts and anarchists, full of innuendo, rumor, and incivility? Hasn’t it shortened our children’s attention spans, truncated their literacy skills, and vaporized their analytical abilities? Hasn’t it utterly destroyed, or at least devalued, the hallowed profession of journalism, whose practitioners in an earlier golden age compulsively double-sourced, carefully weighed all available opinions, disregarded personal views, and delivered only the purest of balanced and densely informative copy?

A generation or two ago, the ability of Orson Welles to deceive the nation, or even that of Franklin Roosevelt to dominate the airwaves, sparked similar concerns. Further, if such worries don’t remind you of Plato’s dislike of poetry and the other imitative arts, of the calumny hurled at vernacular Bibles by the Catholic Church, and of the monk Filippo de Strata’s prediction that the octavos of Ovid cranked out by the “brothel of the printing presses” would make young women wanton, then you have not been paying attention. The criticisms you are hearing are simply the age-old howls of communications elites facing the imminent loss of status and income.

Another argument made against the Web is that it has “rewired our brains” and robbed us of our ability to focus, concentrate, and think deeply. The most prominent proponent of this view, Nicholas Carr, wrote a famous piece in the Atlantic Monthly—“Is Google Making Us Stupid?”—as well as a book-length offering, The Shallows.

His evidence centers on his own anecdotal observations and laboratory experiments that examine how Internet exposure affects performance on measurements of memory and concentration, and how eye movement patterns involved in reading Web pages are different from those involved in reading a printed page. Carr also leans heavily on work showing that extended hours of Web surfing change patterns of brain metabolism observed on specially designed MRI scans.39

His observations would not surprise any brain researcher; the human nervous system is highly “plastic” and able to rearrange its patterns of activity and even its synapses—the actual connections among brain cells. Blindness, for example, redeploys some of the rear areas of the cerebral hemispheres that normally serve vision to the perception of touch and sound, which develop greater importance in the sightless.40

Brain tissue is precious, and reassigning some of it to one activity makes it unavailable for other tasks. Does the Web rewire your brain? You bet; so does everything you actively do or passively experience. Literacy is possibly the most potent cerebral rewirer of all; for five thousand years, humans have been reassigning brain areas formerly needed for survival in the natural environment to the processing of printed abstractions. Some of this commandeered real estate has almost certainly been grabbed, in its turn, by the increasing role of computers and the Internet in everyday postindustrial life. Plus ça change.

Carr also focuses on laboratory experiments demonstrating that Internet use decreases concentration on the initial task at hand.41 One study that especially impressed him found that subjects learned material less well when they had to click through large numbers of hyperlinks.42

Well, yes. A doctorate in neuroscience is not needed to understand that we retain information better if all of it is presented on a single page or screen, as opposed to being chased through a hypertext maze. Real life, on the other hand, is rarely kind enough to supply us with all we need to know about something in one document, and those skilled at following informational threads through different sources will succeed more often than those who expect to be spoon-fed information conveniently packaged between a pair of cardboard covers.

The complexity of everyday life raises a broader point, which is that Web or no Web, human beings are endlessly distractible. On October 21, 2009, a Northwest Airline crew en route to Minneapolis got a little too engrossed in their laptops and overflew their destination by 150 miles.43 For non-pilots, the message is equally clear: if you need to concentrate deeply on a given physical or cognitive task—say, driving a car or legislating, you shouldn’t be playing solitaire or surfing ESPN, as some state representatives were recently caught doing.

From a longer perspective, over the centuries and millennia, technology has endowed humanity with an ever-increasing stream of information as well as the tools to process it. Any technology that accelerates the flow of information carries with it the power to distract and to disrupt. Should we eschew personal computers because they can divert airline pilots, cell phones because they can fluster automobile drivers, and the Web because it supposedly addles nearly all of us?

Figure 9-1. The Great Distractor: Connecticut legislators failing to pay attention to business.

Carr’s thesis almost automatically formulates its own counterargument: life in the developed world increasingly demands non-rote, nonlinear thought. Shouldn’t learning to navigate hypertext skillfully enhance the ability to make rapid connections? Shouldn’t such abilities encourage the sort of nonlinear creative processing demanded by the modern work environment, and make us smarter, more productive, and ultimately more autonomous and fulfilled?

As recently as sixty years ago, high school students spent long hours memorizing vast tracts of literature, from Virgil to Shakespeare to Byron to Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride.” Similarly, in today’s traditional Muslim societies, primary education focuses—sometimes exclusively—on commitment of the Koran to memory. Yes, something was surely lost when the educational process left such memorization behind for calculus, linguistics, evolutionary psychology, and computer science. Yet this shift liberated our neurons from rote learning, and much more was gained in terms of intellectual ability, individual well-being, and societal good. And, as always, both the old and the new styles of education rewired brains in their own ways.

Pop neuroscience—whether pro-Web or anti-Web—aside, scant aggregate-level educational or macroeconomic data support Carr’s hypothesis. In fact, if the citizens of Web-saturated developed nations are losing reading comprehension, then workers’ productivity would plunge; this simply hasn’t happened. Verbal standardized test scores should be declining. Once again, no; over the past thirty years, verbal SAT performance has remained stable. If students are losing the ability to concentrate, then math scores should decrease as well. No again; over the same period, the average math SAT score has increased by twenty-four points.44 If the Web really is making Americans stupid, then shouldn’t citizens of more densely wired nations, such as Estonia, Finland, and Korea, be hit even harder? The question answers itself.

Such concerns recall earlier worries about the inability of laypeople to interpret properly vernacular scripture and the degradation of morals brought about by the printing press. Had Mr. Carr been around in 1470, he no doubt would have been concerned that the flood of frivolous books pouring from the new mechanical presses interfered with the intense concentration needed to hand-copy and illuminate Bibles.

Besides this debate on the effects of prolonged use of the Web on the brain and beyond its unsettling effects on the mainstream media, particularly the newspapers, the Web has clearly empowered ordinary people in free and open societies. Few can deny that it has also done so in undemocratic societies.

On December 17, 2010, a young vegetable seller named Mohammed Bouazizi, who had been shaken down and beaten up by police in the sleepy central Tunisian town of Sidi Bouzid, walked to a local government building, soaked himself with paint thinner, lit a match, and set himself, and the entire nation, aflame. Four weeks later, the nation’s grotesquely corrupt leader, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, fled the country; similar uprisings soon toppled leaders in Egypt, Libya, and Yemen, and threatened to do so in Bahrain.

The Internet played a vital role at every step of Ben Ali’s fall. Ten months before his ouster, WikiLeaks released its massive cache of secret U.S. diplomatic cables. Many of the documents described in great detail the corrupt business dealings, palatial mansions, and overseas buying sprees of what American diplomats referred to as “The Family,” the Mafia-style coterie of relatives and cronies surrounding Ben Ali. The State Department cables riveted Tunisians, and when Bouazizi struck his match three weeks later, the tinder was dry indeed.45

By that point, the Qatar-based network Al Jazeera had warmly embraced the digital age, and so provided the most influential coverage of the unfolding events in Tunisia. As luck would have it, just a month before Bouazizi’s tragic death, its staff had undergone intense training in social media. Al Jazeera obtained a cell phone video of a protest led by Mohammed Bouazizi’s mother; its subsequent broadcast provided many in the Arab world, including Tunisians, with their first news of the evolving events. While it would be disingenuous to point to a single cell phone camera as the spark that ignited the Arab Spring, it speaks volumes that just three months earlier, another protester had immolated himself in a different town, but this event had not been filmed, and so gained no traction.46

Like the Guardian, Al Jazeera understands the full potential of the Internet and of social media. Over the years, it has established a network of reliable volunteers around the Arab world that replaced the old-style permanent local news bureaus, and it has even largely eliminated the need to fly out correspondents to cover breaking events.47

Inside Tunisia, a shadowy dissident organization, Takriz, had gained vital online skills as its members hacked into Tunisia’s expensive Internet service providers. The group allied itself with “Ultras,” violent soccer fans in both Tunisia and Egypt whose informal organizational style and grievances against the regime proved useful to the pro-democracy activists.48 Takriz also forged online alliances with labor leaders, particularly in the mining town at Gafsa. It also found Facebook invaluable, especially in spreading the shocking images of Bouazizi’s immolation and gruesome final days.

Almost as soon as Ben Ali had abandoned Tunisia, Egyptians rose up en masse. At nearly every step, both Web-based news sources and social media tools, chiefly Facebook, helped assemble the crowds at Tahrir Square that eventually would end the decades-long rule of Hosni Mubarak.

As in Tunisia, Egyptian activists found their links with organized labor invaluable. When textile workers in the Nile delta mill town of Mahalla planned a strike for April 6, 2008, this caught the attention of Ahmed Maher, an unemployed, tech-savvy twenty-seven-year-old civil engineer. Maher decided to organize a demonstration in Cairo in support of the strike in Mahalla; he tried everything he could think of: blogs, leaflets, and Internet forums. Nothing, though, seemed to work as well as Facebook, which attracted three thousand new followers per day.49

The Cairo demonstration not only drew thousands of protesters but also occasioned Maher’s arrest and beating, and a graphic threat of rape. After his release, he and his colleagues boned up on nonviolent civil disobedience and organized themselves as the April 6 Movement, after the day of the Mahalla strike. Critically, they contacted Optor, a youth movement founded by Serbian dissidents, who had helped overthrow Slobodan Miloševic´, and the Egyptians sent a member to Belgrade for training. He returned with two tools. The first was a computer game called “A Force More Powerful,” which allows dissidents to simulate different anti-regime strategies.50 The second was a copy of From Dictatorship to Democracy, a 1993 monograph by an American academic, Gene Sharp: a step-by-step playbook for dismantling totalitarian regimes that over the years has drawn wrath from sources as varied as Myanmar’s government and Hugo Chávez.51

On June 6, 2010, police in Alexandria beat to death a young Egyptian man, Khaled Said, probably for filming them as they divided up some illegal drugs. Soon a Facebook page called “We are all Khaled Said” appeared; it featured photos and videos of Said in happier days as well as of his mangled corpse.52 The page attracted nearly half a million members and so caught the attention of the April 6 Movement, one of whose members connected anonymously with the site’s mysterious creator, who communicated only through Google’s instant messaging service. Between the hard-won street smarts of the April 6 Movement and the on-the-fly innovation and savvy mass-market draw of the Facebook site “We are all Khaled Said,” the dissidents swiftly and deftly assembled several different crowds from outlying mosques that converged on Tahrir Square on January 25, 2011.53

Although the creator of the Facebook page, a Google executive named Wael Ghonim, had managed to remain anonymous to the site’s readers and to the demonstrators he had helped organize, the police identified him and arrested him on January 27. When the authorities finally released Ghonim on February 7, he revealed his role in “We are all Khalid Said” and found himself the recipient of a tumultuous welcome in Tahrir Square.54

In both Tunisia and Egypt—and this is also true of every other Middle East regime challenged by substantive protest—the authorities at some point shut off Internet service. This measure usually backfires, as it angers the uncommitted populace and draws people to public spaces, away from the blogs and Facebook pages on their monitors. At the time that the Egyptian government threw the off switch, a communications professor at the University of North Carolina, Mohammed el-Nawawy, described with remarkable prescience how the shutdown would fail: “The government has made a big mistake taking away the option at people’s fingertips. They’re taking their frustrations to the streets.”55 Just as the Soviet Union could not shield its population from radio stations broadcasting from West Berlin and Washington, Arab governments cannot lightly cut off Web feeds from Qatar and London.

The digital infrastructure of the Arab Spring uprisings cannot help inspiring optimism about the prospects for democratic progress in the developing world, and the stories of Trent Lott, Duke Cunningham, Catholic priests’ sex abuse, and WikiLeaks, among many, many others, augur well for the survival of open political institutions in the West.

It is even fair to ask if the Rwandan genocide could have occurred today. Recall the heartbreaking words of Nick Hughes, the cameraman who caught some of the few actual clips of the killing: “If only there had been more such images.”

Now, there will be: as this is being written, Rwanda has 2.4 million cell phone subscribers out of a population of 11.4 million; that number will only increase, as will the number of Rwandan phones equipped with cameras.56 The hope for the new two-way digital media is that they will provide more images, and, accordingly, fewer atrocities not only in Africa, but in the rest of the world as well; since genocide requires secrecy, we might even reasonably hope that Twitter has made it less frequent and more localized.

Admittedly, in the past exciting new communications technologies have lulled otherwise dispassionate observers into gullible optimism; the telegraph, contrary to the expectations of many, did not usher in world peace; neither did radio, despite the millennialist predictions of its boosters. As put by Paul Krugman:

In 1979 everyone knew that it was a Malthusian world, that the energy crisis was just the beginning of a global struggle for ever-scarcer resources. In 1989 everyone knew that the big story was the struggle for the key manufacturing sectors, and that the winners would be those countries with coherent top-down industrial policies, whose companies weren’t subject to the short-term pressures of financial markets. And in 1999 everybody knows that it’s a global knowledge economy, where only those countries that tear down their walls, and open themselves to the winds of electronic commerce, will succeed. I wonder what everybody will know in 2009?57

In 2009, and certainly in 2012, “everyone knows” that the Internet so empowers ordinary citizens that it is only a matter of time before the world is free of despots, and democracy reigns everywhere and forever. Tragically, this is unlikely in nations dominated by conservative, traditional, religiously dominated cultures.

An appropriate amount of “cyberpessimism” about the prospects for democracy in the developing world is in order for at least two reasons. First, in those nations where troops obey orders to fire on demonstrators or where leaders are willing to starve their people into submission, as in Syria and North Korea, monarchs and despots will not fall. As long as Bashar al-Assad can train artillery fire on his populace, and as long as the North Korean leadership can keep its people so deprived of sustenance that they lack the strength to revolt, and as long as these leaders can retain the support of external allies like Russia and China, they will remain in power. Tweets, blogs, and Facebook pages do not effect revolutions all by themselves; the people who read them do—people who must take to the streets and suffer casualties.

Nor is that all; soldiers must at some point decide to stop killing their fellow citizens. It is at this nexus of dissidents, soldiers, and their leaders that the Internet exerts its real, but by no means miraculous, effect: to increase the cost of killing and repression.

This dynamic was already evident in the more primitive communications milieu of the Soviet Union’s last years. As we saw in Chapter 8, in late August 1991, spetznaz commanders, who had already been savaged by the revelations of Latvian TV cameras, the Voices, and their own leaders, decided not to attack Boris Yeltsin and his supporters at the Russian White House barricades. Two decades later, the Internet and social media have further increased the cost of repression to those who undertake it. As the Arab Spring has already demonstrated, the number of despots who will be willing to pay that price has decreased, and so has the number of soldiers and police prepared to obey a despot’s orders. Still, as the civil war in Syria shows, neither has that number reached zero.

Just as the Catholic Church over time co-opted the printing press to its needs, so too have repressive regimes adapted the Internet and social media to theirs. In particular, Iran has demonstrated how technologically adept despots can turn the Web’s connective ability to their own advantage. That nation’s repressive government has applied the usual sorts of filtering techniques and temporary slowdowns/shutdowns used by despotic regimes, similar to China’s “Great Firewall.” The Iranians routinely threaten expatriate bloggers by email, and they intimidate, interrogate, and jail these bloggers’ relatives back home. Immigration officials regularly require returnees to log into their Facebook accounts.58 When anti-regime Green Movement demonstrations roiled Iran in late 2009, the government uploaded photos of demonstrations with participants’ faces circled in red—digital-age wanted posters. A pro-regime cleric duly appeared on television and ordered religious Iranians to report the demonstrators’ identities to a dedicated hotline or Web site.59

In 2009, Western observers were stunned to learn that the Iranians had also deployed “deep-packet inspection,” a leading-edge data analytical tool that sifts through traffic for subversive key words and phrases. Almost all Iranian Internet traffic passes through a single node in Tehran. Its equipment—and the snooping software—were thoughtfully provided by the democratic West in the form of a Nokia-Siemens joint venture, whose spokesman tartly observed, “If you sell networks, you also, intrinsically, sell the capability to intercept any communication that runs over them.”60

The good news is that for the first time in history, ordinary people now have access to similar advanced technologies. A kaleidoscopic global cat-and-mouse cyberbattle is being fought on an ever more level playing field between the oppressed and their oppressors, and the latter’s job descriptions keep getting harder.

Even so, the reasons for pessimism over the prospects for democracy in the developing world go far deeper than the online balance of power between rulers and ruled. The unavoidable fact is that, generally speaking, vigorous and stable democratic institutions do not thrive in poor nations with traditional cultures.

Why is this? An observation by Laureano Lopez Rodo, one of Francisco Franco’s economic officials in the 1950s and 1960s, supplies the essential clue. At that time, Spain stood alone among western Europe’s major nations as a dictatorship; Lopez Rodo famously stated that the country would be ready for democracy only after per capita income reached $2,000 per year. Democracy did come to Spain in 1975, when per capita GDP reached $2,446.61 It did not hurt, of course, that Franco died in that year, but even so Spanish democracy just squeaked by in the rocky years that followed, a period that included the 1981 armed takeover of the Congress of Deputies; had the dictator met his end in an earlier, less wealthy era, the democratic transition probably would have failed.

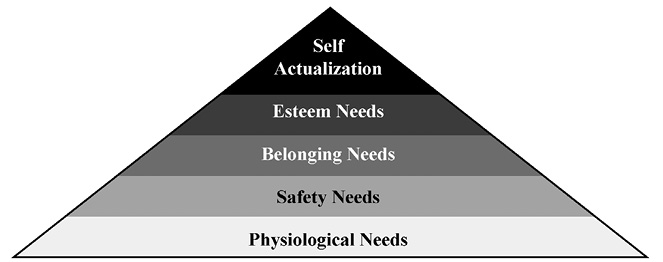

Why is an average annual income of $2,000 (in 1965 currency, roughly $14,000 today) democracy’s magic number? Abraham Maslow’s “hierarchy of needs” provides the answer. In 1943, Maslow, a psychology professor at Brandeis University, published “A Theory of Human Motivation,” a paper in which he proposed a model of psychological behavior and drives.62 Imagine that someone has forced a thick plastic bag over your head and obstructed your airflow; all other urges and desires, including hunger, thirst, or even a strong desire to empty your bladder, will instantly disappear, and you will focus completely on removing the bag.

Only after you resume breathing do you attend to your hunger, thirst, and bladder, and only after these basic physiologic needs have been met will you attack the next rung up on Maslow’s pyramid, your safety needs: a roof over your head and personal security.

Next comes the third rung: the love of family and friends and a sense of community; after those have been attained, humans seek the fourth rung: the respect of others for one’s integrity, strength of character, and intellectual and physical ability.

Maslow postulated that after a person has secured the first four levels—physiological needs, safety, love, and respect—he or she seeks “self-actualization,” a poorly defined state of inner personal satisfaction with one’s creativity, talent, and moral role in the larger world.

In recent decades, sociologists and psychologists have criticized Maslow’s pyramid as oversimplified and have doubted its relevance to the real world, yet at the international level, it has stood up tolerably well to empirical study.63 Moreover, it provides a powerful way of understanding exactly how nations transition to democracy, and, implicitly, of understanding the limits of communications technology in that transition.

Where do democratic ideals “sit” on Maslow’s pyramid? Certainly not on the first two levels: people who are hungry, lack adequate shelter, and fear for the safety of their families and themselves place political freedom far down on their list of priorities. Democracy exists on the upper rungs of Maslow’s pyramid—roughly speaking, only in societies that have adequately, fed, housed, and protected their citizens; hence, Lopez Rodo’s $2,000 per year.

Many observers have made the link between democracy and prosperity. The political scientist Seymour Martin Lipset, in a famous 1959 paper, explicitly drew the connection and backed it up with what was, for the era, fairly sophisticated statistical analysis. He concluded, “The more well-to-do a nation, the greater the chances that it will sustain democracy.”64 But did democracy result in prosperity, did prosperity encourage democracy, or was there some other factor that resulted in both? Lipset suspected, but could not prove, that wealth itself was the causative factor.

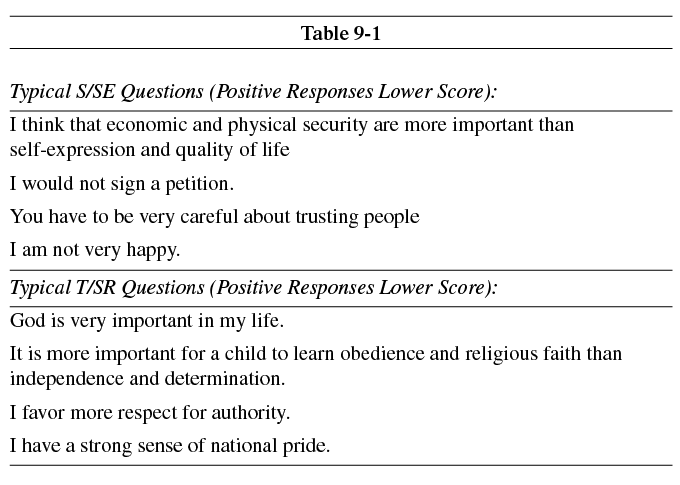

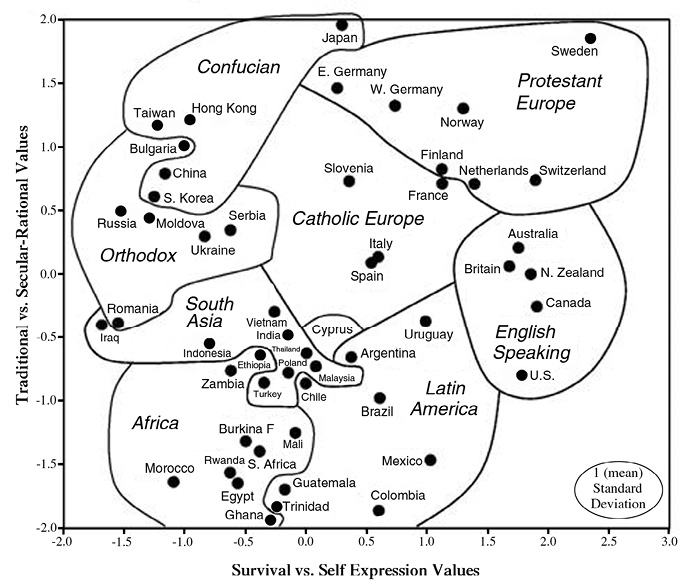

Recent data strongly confirm his hunch. Beginning in 1981, a consortium of social scientists, the World Values Survey (WVS), began to measure a very wide range of beliefs and attitudes around the globe. Typical of their work are the efforts of two pioneering researchers, Ronald Inglehart and Christian Welzel, who have analyzed and sorted nations according to two sociological measures. The first one of these is the “survival versus self expression” (S/SE) score—roughly, how far up Maslow’s pyramid a nation’s population has ascended. The second, the “traditional versus secular-rational” (T/SR) score, is a measure of how tolerant and socially liberal a society is—particularly regarding religion and respect for authority.

This type of analysis groups nations according to religion and culture, as seen in Figure 9-2.

Note how the most democratic nations cluster in the upper right part of the plot—that is, the nations with the highest S/SE and T/SR scores. The most surprising data point is the United States, which looks much more like a Latin American nation than one from the Western developed world: it is high up on Maslow’s pyramid, but as socially and religiously conservative as, say, Iraq or Indonesia.