2

Now the Phoenicians . . . introduced into Greece upon their arrival a great variety of arts, among the rest that of writing, whereof the Greeks till then had, as I think, been ignorant.—Herodotus

They don’t make archaeologists like Flinders Petrie any more.

Petrie’s background was characteristic of eccentric British inventors, adventurers, and academics of his era: Scottish clergy and distinguished empire-serving forebears scattered around the globe, all leavened with moderate, but not excessive, financial comfort.

Typical of his family was his maternal grandfather, Matthew Flinders, who surveyed Australia (particularly the Great Barrier Reef and Gulf of Carpentaria), wrote treatises on magnetism, and invented the Flinders Bar, which is used to this day to compensate for the compass error caused by the iron in ships’ hulls. His name is well known to Australian schoolchildren, and the country is thick with cities, streets, and even an island, a river, and a mountain range named after him; each year large numbers of Aussies make the pilgrimage to his birthplace, Donnington, in Lincolnshire.1

Matthew raised an accomplished French-speaking daughter, Anne, who was courted by William Petrie, an unsuccessful inventor who had tinkered with electrical and magnetic inventions. Before they could marry and raise a family, William would need to land a paying job, which he finally did at a chemical factory in 1851. On June 3, 1853, William Matthew Flinders Petrie was born.

Young Willie, as he was called, quickly demonstrated a thirst for knowledge; by age nine, he had digested his father’s thousand-page chemistry text. Nothing, however, fascinated him as much as old objects, particularly his mother’s collection of minerals and fossils.

After Willie had a disastrous experience with an overly strict governess/tutor, his physician recommended that he be kept out of school, so he never obtained a formal education. He soon fell under the influence of a self-educated polymath, N. T. Riley, the proprietor of a local antique shop. Petrie thrived amid Riley’s collection of tripods, sextants, and coins, and under his tutelage became an expert surveyor and numismatist.

In Riley’s shop, Petrie acquired a talent for authenticating rare coins. This, in turn, attracted the attention of a customer of Riley’s, the Coins and Medals curator at the British Museum. By age twenty-one Petrie was awarded a coveted reader’s ticket at the museum, which became his university. In addition, Petrie’s surveying skills turned him into a meticulous archaeologist. When he discovered that the museum’s Map Room contained no accurate surveys of England’s most prominent ancient stone circles, he plotted numerous sites, including Stonehenge, over the next several years.

Petrie developed a fascination with the Egyptian pyramids, both from his work at the museum and, curiously, from Piazzi Smyth, the author of a crackpot volume, Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramid. Smyth posited that, since according to the strict interpretation of scripture, the world was created in 4004 BC, the Egyptians could not possibly have mustered the expertise to have built the pyramids by the third or second millennium BC. Reasoning that the pyramids could only have been divine creations, Smyth scavenged all manner of evidence in support of this idea, most prominently the 3.14 ratio of their circumference to their height—the approximate value of pi. Petrie began corresponding with Smyth and publishing pamphlets in support of Smyth’s theories, but the two soon fell out regarding theological matters.

Petrie resolved to learn the truth about the pyramids, and in 1880 he sailed to Alexandria and so began a six-decade career as one of England’s greatest Egyptologists. He accomplished seminal surveys of the pyramids, along with hundreds of other sites in the Levant.2

In February, 1905, after exploring the Middle East for more than two decades, Petrie and his wife arrived at an old turquoise formation in the western Sinai at Serabit el-Khadim, which had been mined as recently as fifty years before by a retired English major and his family. There, although he and others did not realize it for years, Petrie made the most important discovery of his career.

Figure 2-1. The ancient Levant, ca. 800 BC, before the destruction of Israel, Judah, and the Aramaean states.

At the mine the Petries came upon a large collection of statues and inscriptions. Most were expertly carved and bore standard hieroglyphic or hieratic writing, almost certainly produced by the mine’s Egyptian overseers.3

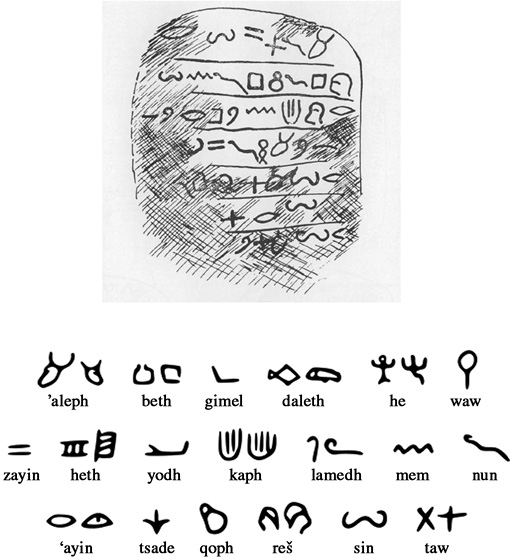

His observant wife Hilda also found some rocks bearing cruder inscriptions. On closer inspection, they noted that this writing included only about thirty or so different symbols that were not recognizably hieroglyphic or hieratic—both hieroglyphic and hieratic writing used about a thousand symbols. Further, these simpler inscriptions always coincided with primitive, non-Egyptian statues; the writing appeared to flow from left to right, also unlike the well-known hieroglyphic, hieratic, or later Phoenician and Hebrew alphabets.

Petrie dated the inscriptions to approximately 1400 BC. He clearly recognized them as an alphabet, and one that preceded by about five hundred years the earliest known Phoenician writing, heretofore felt to be the first alphabet.4 Ironically, Petrie, although proficient at reading Egyptian script, did not possess a broader knowledge of linguistics and failed to realize the full import of his discovery. Although he knew he had found an alphabet much older than Phoenician, he did not think his discovery represented the earliest one. In his book The Formation of the Alphabet, published seven years after his Sinai discoveries, he theorized that the inhabitants of northern Syria had somehow gathered diverse symbols from throughout the Levant into the first workable alphabet; amazingly, he failed to mention his discoveries at Serabit.5

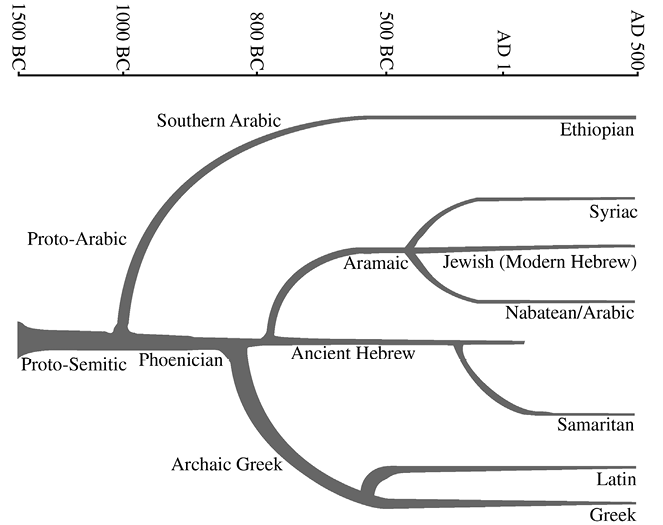

It fell to an Egyptologist, Alan Gardiner, to realize that the Petries had actually stumbled across the origin of the alphabet, or something very close to it. Linguists had long known that Latin script—the everyday alphabet of today’s Western world—evolved from Greek letters, which had themselves derived from Phoenician, as did Hebrew.6

The relationship among all these scripts is ironclad: the very word “alphabet” derives from alpha and beta, the first two letters of the Phoenician, Hebrew, Greek, and Latin scripts, and the sounds and names of the letters, and their alphabetical order as well, are also quite similar. For this reason it is in many cases possible to approximate the sound of a long-lost language if it was written in an alphabetic script.7

All of these alphabets, consisting of between twenty-two and thirty letters, represented nearly identical phonemes—the basic sound units of human speech. Gardiner was the first to realize that the letters found by the Petries at Serabit, or close relatives of these letters, most likely comprised the original alphabetic script. He named the symbols the “proto-Semitic alphabet.”8

Figure 2-2. Early proto-Semitic letters, ca. 1400 BC. Top: Serabit Tablet. Bottom: Proto-Semitic Alphabet.

The last chapter of Petrie’s life befitted his eclectic roots and eccentric personality. During his final hospitalization for malaria in Jerusalem in 1942, he requested that his head be donated to the Royal College of Surgeons in London as a specimen of a typical Englishman. His physicians, understanding the extraordinary nature of his accomplishments and hopeful that the study of his brain might provide medical science insight into the nature of genius, complied. Wartime conditions, however, delayed shipment of Petrie’s pickled cranium back to Britain until after 1945, and when it finally arrived at the Royal College, it was absentmindedly stored away. It was not rediscovered until the 1970s, by which time the examination of great men’s brains had fallen out of favor.9

Over the millennium following the alphabet’s invention around 1500 BC, the simple phonemic lettering system Petrie discovered made possible the first stirrings of mass literacy that would unleash much of the subsequent political and social ferment of human history.

On the basis of archaeological and linguistic evidence, most authorities believe that the proto-Semitic inscriptions the Petries first found at Serabit derived from Egyptian hieratic or hieroglyphic writing. While the precise origin of the proto-Semitic alphabet will never be known, the Serabit inscriptions suggest that it was probably invented somewhere in the Sinai or Canaan by non-Egyptian Semites who had come there from somewhere in the Levant to work as miners for the Egyptians.

Did the first simplified alphabetic script really originate in the mines at Serabit? After Flinders’ excavations there, archaeologists uncovered, at several other sites in Palestine, more primitive inscriptions that look alphabetic and possibly predate the Serabit inscriptions by as much as a century or two. More recently, an American research team has uncovered proto-Semitic inscriptions at Wadi el-Hol, several hundred miles south of Serabit el-Khadim, on the Nile; they suggest that the Egyptians may have in fact invented the script to better communicate with their Semitic workers/slaves.10

Another intriguing candidate for “inventor of the alphabet” is the Midianites, a Sinai people who mined copper and who could have derived it from the writing of their Egyptian overseers in the same way as did the miners of Serabit. The Bible has Moses marrying Zipporah, the daughter of the Midianite high priest Jethro, who himself was probably literate. Did Moses’s father-in-law teach him how to read and write?11 Whatever the ultimate truth of the matter, it seems probable that the Serabit script or one of its close and never-to-be-discovered relatives gave rise to all of the modern Western alphabets.

The Jewish people’s supposed escape from slavery in Egypt—the Exodus—happened at approximately the same time as the creation of the Serabit inscriptions. Unfortunately, biblical scholars have great difficulty pinpointing the time of the Exodus. Many, in fact, go further, and suggest that it never occurred, but rather that the ancient Israelites evolved from the native Canaanite communities. Nor, for that matter, has the historical existence of Moses been substantiated with archaeological data or independent written sources.12

If the Exodus did take place, it must have happened sometime between the rise of the Iron Age empires of the Nile around 1550 BC and the first Egyptian mention of the people of Israel around 1200 BC. Coincidentally, roughly halfway between these two dates, Pharaoh Amenhotep IV (Akhenaten) convulsed Egyptian society by establishing a “monotheistic” belief system centering on the sun-disk deity Aten; some have speculated that Moses was influenced by Atenism, or was perhaps even a believer. Thus, in the middle of the second millennium, the Egypt/Sinai area saw the advent of Western monotheism, starting with the first short-lived Egyptian dalliance, followed by the more permanent Hebrew variety, the putative Exodus, and the invention of the alphabet.

The temporal and geographic connection between the alphabet and monotheism in Egypt-Palestine during the middle of the second millennium may be more than coincidence. What might tie them together? The notion of a disembodied, formless, all-seeing, and ever-present supreme being requires a far more abstract frame of mind than that needed for the older plethora of anthropomorphized beings who oversaw the heavenly bodies, the crops, fertility, and the seas. Alphabetic writing requires the same high degree of abstraction and may have provided a literate priestly caste with the intellectual tools necessary to imagine a belief system overseen by a single disembodied deity. Whatever the reason, Judaism and the West acquired their God and their Book.

From the modern perspective, it seems inevitable that the complex cuneiform writing system described in Chapter 1 would succumb to the simpler, more nimble alphabetic system, as indeed in the end it did. Yet cuneiform survived longer than any other system—over three millennia—before it finally fell into disuse sometime around the first century after Christ.

The demise of cuneiform was largely the work of an obscure Semitic tribe living on the western fringes of the great Mesopotamian empires. Modern people dimly remember that Jesus spoke Aramaic, but few, even among contemporary practicing Jews, recall that so did the majority of his fellow Jews.13 Fewer still realize that the modern “Hebrew alphabet” is actually Aramaic. The silent tragedy of the Aramaeans is that they created a language and alphabet that long outlived their culture and civilization.

Like the Hebrews, the Aramaeans began as desert and semidesert nomads. During the second millennium BC, they gradually settled in the northern Levant and in the far northwest of Mesopotamia. By 1200 BC they had founded what eventually became one of their capitals, Damascus. As with the classical period Greeks, there was no single Aramaean state, but rather a host of small city-states and tribal confederations. While the Aramaeans gradually assimilated the cultures of the Canaanites and Amorites who surrounded them, they kept their distinctive language and—far more important—their own easy-to-learn version of the proto-Semitic script discovered by the Petries.

At the same time that the Aramaeans adapted the alphabet to their own use, they also benefited from the domestication of the camel and the development of the North Arabian saddle. The combination allowed them to mount in excess of five hundred pounds of cargo on the average animal, and about half a ton on the strongest beasts; a single camel driver, conducting a train of three to six animals, could move a ton or two of cargo between twenty and sixty miles a day. This was one of history’s great transportation revolutions, and it made the Aramaeans the terrestrial equivalent of the Phoenicians: a trading people who spread far and wide a powerful alphabet.14

History intertwined the fates of Hebrews and Aramaeans. When Abraham sought a wife for his son Isaac, he sent a messenger east to the Aramaean city of Harraˉn, in what is now eastern Syria, to fetch Rebekah; Jacob’s wives Leah and Rachel probably hailed from Aramaea as well. Abraham’s migration from northwestern Mesopotamia to Canaan was part of a larger westward movement of Aramaean peoples sometime in the second millennium BC. The conclusion seems inescapable: Abraham himself may have been Aramaean, and wished his son’s seed mingled with the women of his own tribe, and not with the local Canaanite women.15

Generally, the relationship between the Jews and Aramaeans was hostile. Between roughly 1000 BC and 750 BC, dominance seesawed between the two peoples; David briefly occupied Damascus, and a century and a half later the Aramaeans nearly sacked Jerusalem. Less frequently, the Jews and Aramaeans were allied, particularly against the increasingly powerful Assyrians to the east, who, in 853 BC, led by their emperor Shalmaneser III, were held off by a complex coalition of Jews, Aramaeans, and Phoenicians.

In 732 BC, the Aramaeans’ luck ran out. The Assyrians under Tiglath-pileser III took Damascus, pillaged it, and deported its inhabitants to the Euphrates. Ten of the original twelve tribes of Israel disappeared into history with them, lost when the northern Jewish kingdom of Israel, which had fatefully allied itself with the Aramaeans, also fell victim to the Assyrian hordes.

The Assyrians spared the southern Jewish state of Judah and its capital at Jerusalem for reasons that remain controversial to this day. The traditional view, supported mainly by biblical evidence, is that Judah’s wily King Ahaz resisted alliance with the Aramaeans and the northern kingdom of Israel. Instead, he made his kingdom a vassal state of Assyria, which, in exchange for an annual tribute of silver, and perhaps some military assistance as well, would have allowed the Jews nearly complete autonomy. Another view has the southern kingdom surviving because of disease among the Assyrian armies; still another is that the Assyrians wished to maintain Judah as an independent buffer state against Assyria’s major rival to the west, Egypt.

Whatever the reason, Judah would outlive the northern kingdom of Israel. Ahaz’ son Hezekiah was less favorably disposed toward the Assyrians, and after he succeeded his father around 715 BC, it was only a matter of time before hostilities erupted. In 704 BC, after the mighty Assyrian emperor Sargon II was killed in a military campaign, Hezekiah decided to test the new emperor, Sennacherib, by stopping tribute payments. This was a near-fatal misstep; it prompted a devastating siege of Jerusalem in 701 BC that brought starvation, but not conquest, to the Jews.

The Assyrians usually made an example of such outright rebellion; around the same time as Sennacherib’s siege of Jerusalem, Babylon also revolted, and Sennacherib was said to have spilled so much blood into the Euphrates that the Persian Gulf ran red, informing all on its shores of the costs of opposing him. Yet in the end, Sennacherib spared Jerusalem.

After the fall of the kingdom of Israel, Judah survived for nearly another century and a half until its final, horrifying conquest in the high summer of 587 BC by Nebuchadnezzar’s Babylonians (the conquerors of the overextended Assyrians), which brought the burning of Jerusalem and the deportation of the Jews to the banks of the Euphrates. The Assyrians’ earlier decision to spare the southern kingdom proved one of history’s fulcrums, for at least two reasons. First, it allowed the Jews, and their cultural contribution to the West, to survive. Second, the sparing of the southern state resulted in a socioeconomic transformation that probably produced mankind’s first small step toward mass literacy. While mass literacy requires both a simplified alphabet and readily available writing implements, they are not in and of themselves sufficient. Literacy is also spurred by two other conditions: prosperity, which gives people the leisure to pursue it; and urbanization, which provides the critical mass of human contact to propagate it.

In the wake of Israel’s fall, Judah received large numbers of northern refugees who possessed in abundance all four of the requirements for literacy. The proximity of the northern state to Phoenicia gave it access to both that culture’s alphabet and, critically, to supplies of papyrus shipped from Egypt. In addition, Judah’s flat terrain (at least compared with that of the more hilly Israel) made for a more urban, sophisticated, and thus literate society.

The flood of transplanted northerners transformed the agrarian and less sophisticated south and probably produced a significant increase of literacy among its inhabitants. After 700 BC, the Judeans probably consumed ever-increasing supplies of papyrus, but the ravages of time have allowed for the recovery of only one fragmentary specimen from this period. The papyrus may have perished, but the inscribed seals used to close the letters and documents survived, and the period’s intellectual awakening is reflected in the appearance of large numbers of these round, durable artifacts in the southern kingdom after 700 BC. Many of these seals are crudely crafted and misspelled, suggesting that they were the work of ordinary citizens.

In the Old Testament, the Book of Jeremiah’s famous Chapter 36 supplies another clue to the extent of Judean literacy in this period. The passage begins with the Lord informing the erstwhile prophet of His displeasure at the idolatry, blasphemy, and immorality of his chosen people. Jeremiah calls on the scribe Baruch to take some dictation.

The year is approximately 605 BC, and the Babylonians loom menacingly on the eastern horizon. Jeremiah warns the Judean king, Jehoiakim, and his people to repent lest the Lord, through the Babylonians, his chosen agents of destruction, annihilate Judah:

Then read Baruch in the book the words of Jeremiah in the house of the lord, in the chamber of Gemariah the son of Shaphan the scribe, in the higher court, at the entry of the new gate of the lord’s house, in the ears of all the people.16

By and by, Jehoiakim’s minions take the scroll and bring it to the king. Not surprisingly, the king is displeased; as his scribes read the document, he cuts off successive parts of it, throws them into the fire, and orders the arrest of Jeremiah and Baruch, whom the Lord conveniently hides. In the chapter’s final verse, Jeremiah dictates yet another scroll to Baruch.

By Jeremiah’s time—very roughly, 600 BC—the Hebrews had employed their alphabet for centuries, yet the average Judean remained largely illiterate. There is not even the absolute certainty that Jeremiah could read. Further, the entirety of the Old Testament, written mainly during the first millennium BC, shows the classic signs of having its origins in a largely illiterate, oral tradition: the use of meter, formulaic exposition, repetition, and, most characteristically, epithets. For example, of the twenty-three mentions of Baruch in Jeremiah, eight are “Baruch son of Neriah.”17

Just as clearly, the written word had the power to sway the people; while ultimately this prophecy did not save Judah from itself or from the Babylonians’ wrath, Jeremiah would probably not have commanded the people’s attention without the magic and amplifying power of the scroll.

Around 588 BC, as Nebuchadnezzar was systematically reducing Judah to rubble, either as Yaweh’s agent of divine retribution or on his own account, he besieged the fortress of Lachish, about thirty miles southwest of Jerusalem. Archaeologists excavating the site have found numerous ostraca—inscribed pottery shards—written during the chaos of the fort’s final days. The most famous is the so-called Lachish Letter 3, or “Letter of a Literate Soldier,” an apparently complete text of about one hundred fifty words written by Hoshayahu, most probably a junior officer, to his commander, Yaush. Apparently Yaush had suggested that the soldier employ a scribe, at which the latter took great offense: “As God lives, never has any man read a letter to me.” The entire letter actually consists of the soldier’s anger at such an offensive slur: “And also every letter that comes to me, surely I read it and, moreover, I can repeat it completely!”18

Hoshayahu’s letter contains slang, and this was almost certainly the proximate cause of the commander’s recommendation that his underling hire a scribe. Nonetheless, this letter provides one of the first indications of the spread of literacy down to at least mid-level officers and, further, that a stigma was becoming attached to illiteracy.

Many have used such vignettes, particularly biblical passages, to overestimate the extent of literacy in Judah. In the first place, we must define what is meant by “literacy.” In the full modern sense of the word—reasonable fluency and accuracy with both reading and writing—certainly not more than a few percent of the population qualified. Because papyrus was expensive, many more people could read than write. Also, there was little to read: only scattered stone inscriptions and a relatively small number of papyrus scrolls secreted away in temples, palaces, and the homes of the very wealthy. Scribes wrote and stored records, but literature and the arts of storytelling and poetry remained almost exclusively oral activities.

Other barriers kept a lid on the literacy rate as well: the likely absence of organized schooling in Judah and the fact that before the medieval period, scribal practices paid little attention to evenness of script, line breaks, or sometimes even word breaks. Reading was a laborious process that was meant to be performed aloud—even in the modern world accounts are “audited.” The practice of silent reading would not become common until almost the modern period, and some linguists argue that while most modern Western languages are easy to read silently, the ancient Semitic languages, particularly vowel-less Hebrew, could not be read silently, a contention that most bar and bat mitzvah boys and girls would surely agree with.19

In the words of biblical scholar David Carr,

When you list those people who are depicted as writing in ancient Israel, it quickly becomes evident that virtually all are some sort of official. Aside from God, who is one of the Bible’s most prolific writers, virtually all writers and readers in the Bible are officials of some kind: scribes, kings, priests, and other bureaucrats.20

Baruch’s scrolls may have had only limited effect, and Hoshayahu’s letter may have been of only modest quality. Both, however, were symptomatic of the first feeble efforts by ordinary people at wresting the lever of literacy from the hands of the state.

Forty years after Nebuchadnezzar burned Jerusalem and deported the Judeans, the Babylonians in their turn fell to the Persians under Cyrus, who allowed the Jews to return home.21 Because the Judean exile was only fifty years old when Cyrus vanquished the Babylonians, the Judeans who made the fearsome trek across the Syrian Desert back to their ancient homeland easily retained their cultural heritage, which survives to the present day. But this was not true of the northern kingdom’s population, who by that point had been in exile for nearly two centuries, long enough to erase their religious and ethnic identity; Israel’s ten tribes would remain forever “lost.”22

By 600 BC, Aramaic became the dominant language and script of the Land Between the Rivers, and it bound together the Babylonians and the subject peoples they had sent into exile there. It became the lingua franca first of the Mesopotamian empires and then of the Persian Empire, and it would later battle Greek and Latin for linguistic dominance in the Middle East.23

Why was Aramaic so successful? The French physician turned historian Georges Roux ascribed the dominance of the language of the Aramaeans

partly to the sheer weight of their number and partly to the fact that they adopted, instead of the cumbersome cuneiform writing, the Phoenician alphabet slightly modified, and carried everywhere with them the simple, practical script of the future. As early as the eighth century BC Aramaic language and writing competed with the Akkadian language and script in Assyria, and thereafter gradually spread throughout the Orient.24

The Aramaeans also, for the first time in the ancient world, began to separate their words, not only with small spaces, but also by inventing a “final” form for letters when they were used at the end of a word, which also denoted a word space.25

Sometime toward the end of the second millennium BC, the Aramaeans evolved into a trading people who occupied the corridor between the Phoenicians in the west and the Mesopotamians in the east. The utility of their new script became immediately apparent to the Assyrians, Babylonians, and Persians, and to their subject peoples. A famous biblical passage attests to the use of Aramaic as the diplomatic language of the Middle East as early as the end of the eighth century BC, when Jerusalem was besieged by the Assyrian king. His cupbearer Rab-shakeh approaches the city to demand surrender. Hezekiah’s representatives beg Rab-shakeh to speak to them in Aramaic, the diplomatic language of the day, so Judah’s citizens will not understand their desperate situation. The cupbearer, however, springs a surprise: speaking in Hebrew, he urges Jerusalem’s citizens to capitulate and reveals to the city’s population how dire the situation has become.26

At first, Assyrians and Babylonians wrote summaries of their cuneiform tablets in the compact Aramaic script along their thicker outside edges, like the spines of modern books, so that their contents could be ascertained while the tablets were stacked. Gradually, Aramaic script spread to the inside of the tablets, which over time evolved into an all-Aramaic format.27

Another reason for the spread of the script may simply have been the commercial vitality of the Aramaeans, who were to the deserts of the northern Levantine region what the Phoenicians were to the sea, trading particularly in copper, ivory, incense, and textiles of all descriptions. Whatever the reason, with each change of political dominance, from Assyrian to Babylonian, and from Babylonian to Persian, Aramaic only became more prominent.

Figure 2-3. The evolutionary tree of the Western alphabets.

Sometime around 525 BC, the Persians began to experiment with an alphabetic form of cuneiform, the “old Persian” script decoded by Rawlinson. This innovation was short-lived; Darius I, the second successor to Cyrus and author of the Bisitun inscriptions, ultimately discarded it in favor of Aramaic as the language of his empire. Aramaic remained the lingua franca in the Middle East until it was eclipsed, first by Greek in the wake of Alexander’s conquests, and then by Arabic in the seventh century after Christ, following Islam’s initial conquests.

The Jews did not migrate back to Palestine all at once upon their emancipation by Cyrus in 539 BC. Among the most important later returnees was a group led by the prophet Ezra, who was also a scribe and who probably came to Jerusalem about 450 BC. He bore the now familiar square Aramaic alphabet, which he spread along with his influence in Palestine. It rapidly supplanted the original Hebrew alphabet, and within a few centuries spoken Hebrew largely disappeared along with it, living on only, as Sumerian before it and Latin after it, in liturgy.28

As influential as the Aramaic script became, it would be the simplicity and elegance of Greek letters that would change the very nature of human politics. The first literate people to occupy Greece, the Mycenaeans, settled the region around 1600 BC, and, like the Egyptians and Mesopotamians, they employed a syllabic script, so-called Linear B (derived from the Minoan Linear A). As in Mesopotamia and Egypt, this writing served only administrative and record-keeping purposes, and it vanished when this civilization mysteriously disappeared around 1100 BC. The region remained illiterate throughout the subsequent Greek “Dark Age,” which would end with the arrival of Phoenicians on the Aegean scene.

The Phoenicians were one of the world’s first peoples to engage in direct, long-distance commerce; the Bible records that their vessels returned from India with large amounts of gold around 950 BC, and Herodotus relates an astonishing Phoenician circumnavigation of Africa around 600 BC.29 Sometime after 800 BC, one of their vessels traveled from Phoenicia to Greece with an even more precious cargo: the Phoenician script, derived from the proto-Semitic.

Only the precise timing and geography of this transfer stir debate among specialists, who have long noted that the first Greek inscriptions, which date to roughly the eighth century BC, strongly resemble the Phoenician script of the same era. Phoenician traders, the only people at that time capable of routinely braving the entirety of the Great Sea, must have effected this fateful transfer of information technology.30

The Greeks, however, made one critical change to the Phoenician system: they converted several unneeded consonant symbols into vowels, thus eliminating nearly all the phonemic ambiguity of all of the older alphabetic systems. As discussed in the Introduction and Chapter 1, syllabic systems, with their hundreds of symbols, took upwards of a decade to master; consonant-only Semitic systems needed perhaps five years, as evidenced by the use of vowel markings in modern Israeli education until students are about age ten, by which point the vowel markings are abandoned. (Not a few Israelis regret that everyday Hebrew script lacks vowels, which the father of novelist Amos Oz piquantly called “the traffic police of reading.”)31 The average Western child, by contrast, can achieve functional literacy in the unambiguous consonantal/vowel environment of Latin, Greek, or Cyrillic script within a year or two; so, presumably, could the average child in ancient Greece.

Around the same time that the Phoenicians imparted their alphabet to the Greeks, the Egyptian pharaoh granted the Greeks the trading city of Naucratis in the Nile Delta. The Greeks’ main interest in Egypt was grain for feeding the burgeoning Greek population; but along with grain, traders carried another treasure across the sea: papyrus on which to write their new alphabet.32

This combination of papyrus and a vowel-and-consonant alphabet allowed, for the first time in human history, the potential for mass literacy. Imagine a world in which the storage of information is primarily oral. Think first about the parlor game “Whisper Down the Alley,” in which a simple sentence becomes hopelessly garbled by the time it is passed to the third or fourth person. Modern historians estimate that preliterate societies can accurately retain historical information for no more than three generations—not much more than the living memory of a single long-surviving individual.33 Given the extreme fragility of memory for normal conversational speech, how, in the absence of writing, are a family’s, a tribe’s, or even a nation’s essential narratives and skills preserved over the generations and centuries?

By the use of the mnemonics implicit in poetic structure: meter, rhyme, repetition, and the incessant use of stereotyped adjectives. In short, with poetry. Ulysses sailed, not over mere waters, but over the wine-dark sea; the handsome hero of the Trojan War was not just Achilles, but swift-footed Achilles. Further, the storytellers seemed uninterested in character development, at least by means of dialogue; in many instances, the speeches of major characters in the Homeric epics are nearly interchangeable.34 Technical expertise in storytelling also factors in strongly: in preliterate societies, the art of the oral narrative becomes a skilled and valued craft, a feat of memory and performance requiring years of training for the aspiring storyteller.

In the early twentieth century, Harvard classicist Milman Parry noted with great interest the repetition and stylized epithets that saturated the Homeric epics. He further noted that each epithet appeared in the same part of each hexameter line, and if the character had to be mentioned in a different part of the line, a different epithet was used. He realized that Homer—if Homer existed at all—was almost certainly not an “author” in the modern sense, especially since the epics originated in Greece’s preliterate Dark Age. Rather, “Homer” was one storyteller or more than one—perhaps many—who used poetic/narrative devices to keep the story lines of the Iliad and the Odyssey more or less intact throughout the ages until these epics finally reached the safe harbor of ink and papyrus around the seventh century BC.

A relative of Odysseus who wished to contact him had only one choice: since the Odyssey took place in an illiterate age, a letter could not be sent to or received from the peripatetic hero; rather, the relative would have to get on a ship, sail the wine-dark seas, and find him. In the words of classicist Jennifer Wise, “With little exaggeration, it could be said that the entirety of the Odyssey ultimately boils down to one simple technological problem: the epic hero’s inability to write home.”35

Milman Parry’s mentor at the Sorbonne, the linguist Antoine Meillet, suggested that Parry travel to the Balkans, an area of widespread illiteracy, and also home to the last traditional folk storytellers in Europe, to observe how they learned their craft. Tragically, Parry died of an accidental gunshot wound soon after he returned from Yugoslavia, but his assistant Alfred Lord carried on his work. Eventually, Lord produced the celebrated The Singer of Tales, a detailed description of the years of apprenticeship served by aspiring Yugoslav storytellers, a process likely similar to that undergone by the original tellers of the Iliad and the Odyssey.36

Oral societies, which must of necessity embed information in a complex matrix of meter, rhyme, repetition, and epithet, differ fundamentally from literate societies, in which information can be quickly encoded with a few strokes of the pen or keyboard and then just as rapidly forgotten. Ethnographers and anthropologists almost universally remark on the extraordinary retentive powers of storytellers in oral societies. When the Tahitians alphabetized their language in 1805, some of the first of them to master literacy were said to easily memorize entire books of the New Testament. Even today, the ability of many in Islamic and Indian societies to retain word for word large swaths of literature, particularly traditional and religious texts, amazes Westerners.37

In ancient Greece, the change from oral to written transmission was by no means immediate; the writings of Solon, who laid down some of the first democratic Athenian reforms around 600 BC, are largely in verse. After that time, in the words of the French paleographer Henri-Jean Martin, “All subsequent works among the Greeks and Latins had an author and a birth certificate as soon as they were written.”38 By the time of Plato, in the early to middle fourth century BC, prose had become well established.

Certainly, among the Greeks, and perhaps earlier among the Phoenicians, Hebrews, and Aramaic speakers, something profound had occurred: writing had ceased being the exclusive realm of a professional class—in this case, the scribes. Almost by definition, the term “profession” implies the scarcity of a skill; in the ancient world, the scribe was someone in possession of a rare ability. In the future, other rare communication skills and abilities—particularly the production of books and of print and broadcast journalism—would become more available to the general public, and this would provoke an often fierce backlash by professional castes now shorn of their long-standing privilege and status.

Yet in the fifth century BC, the Greeks themselves commented little on the literacy revolution taking place in their midst, either as to its nature or as to its consequences. The modern historian searches Plato and Aristotle in vain for any expression of pride in, or at least any awareness of, the growing literacy and the political changes it must have wrought. Instead, when the Greeks comment on education in their city-states, we find only lengthy descriptions of military training or of the societal importance of music and gymnastics. The most authoritative modern expert on literacy in ancient Greece, William Harris, notes that while the later Hellenistic Greeks and the Romans occasionally mentioned the literacy of individuals, the classical Greeks almost never did.39

The new literacy evoked recorded commentary in only one area of Greek life: theater. Scores of plays, both comic and tragic, mention all modes of writing, from scrolls to inscriptions to waxed tablets. The new communications technology seems to have obsessed the playwrights. Sophocles, Aristophanes, and Euripides all had actors mime letter shapes with their bodies. One of Callas’s plays, known only from a few surviving fragments, featured the alphabet itself in the starring role, with members of the chorus, like Village People, miming letters with their bodies, both singly and in syllabic pairs: “Beta alpha, ba; beta epsilon, be; beta eta, beˉ . . .” and so forth.40 This production is flippantly known as the “ABC show” among classicists, who have speculated that the actors mimed and danced the letters of the new alphabet with pornographic effect.41

The impact of literacy in Greek theater ran in both directions. From the audience’s perspective, the playwrights crammed so many literary allusions into their productions that Aristophanes joked that those attending the performances, presumably drawn from the Athenian upper classes, came well prepared: “Each a book of the words is holding; never a single point they’ll miss.”42

At the same time, from the performers’ perspectives, literacy itself transformed and expanded their very art. As late as the sixth century BC, public renditions of the orally derived classics, prime among which were the Homeric epics, were “staged” in the traditional fashion: by a solo performer who simply recounted the narrative in formulaic verse.

Sometime in the late sixth century, a resident of Icaria (just north of Athens) named Thespis invented a radically new mode of performance. First, he applied his dramatic talent to the actual creation of new plots and characters, not merely using those from previous oral traditions. And were that not innovation enough, instead of merely narrating a story, he then pretended that he was those characters. This concept of converting storyteller into character must have proved so daunting that the recruitment of additional actors into the performance far exceeded the imagination of even this great innovator. (Thespis’s plays are thought to have consisted of dialogues between one main character and a chorus.)

In order to assume his roles, Thespis initially applied a white lead paste to his face. Too clumsy, too slow. Next, he hid his face with flowers: too flimsy, not realistic enough. Finally, he settled on individual linen masks, which his successors, particularly the playwright and actor Aeschylus, often dyed and painted in vivid colors, to terrifying effect.43 Further, with a permanent written script, his characters could speak in prosaic, everyday language. In short, Thespis became the first playwright and the first actor, and his very name became synonymous in most Western tongues with both actors and acting.

Needless to say, given the vagaries of human memory, without the ability to permanently record words, there can be no soliloquy and no dialogue; indeed, there can be no playwright. Furthermore, without soliloquy and dialogue, there can be little character development.

The written script thus broadened the complexity of character development and dialogue, and this broadening in turn greatly increased the logistic demands of the performance, particularly of the relatively large choruses of Greek dramas and comedies. By the fifth century BC, two of the major Athenian festivals—the Lenaia and City Dionysia—revolved around dramatic competitions. These festivals consumed such a large part of the city-state’s budget that the Festival Fund evolved into one of the most powerful Athenian political institutions, and its commissioners were chosen by direct popular ballot—not by random lot, as were most lesser officials.44 (The only other major officials elected by popular ballot in Athens were the ten strategoi, or generals; and the chief magistrates, that is, the archons.)

Even so, these productions required additional private money from well-endowed benefactors. Just as Athens’ wealthy citizens, known as “trierarchs,” funded and often commanded the massive and expensive hundred-oared trireme warships, so, too, did other rich citizens—choregoi—fund and direct the theatrical choruses.

Alas, history dealt Thespis the short straw: none of his plays survived; only his techniques remain. The intensity of the dramatic competitions in Athens attested to the output of its greatest dramatists: Sophocles is said to have written 123 plays; Aeschylus, about 80; and Euripides, about 95; respectively, only 7, 7, and 17 have survived. Euripides’ relatively good historical fortune resulted from the discovery of a single intact medieval volume, presumably one of several, containing all the plays with titles beginning with the Greek letters eta through kappa.

It is humbling to realize that such a prodigious output arose from, and was aimed at, such a small population base. At its height in the middle of the fifth century BC, Athens had only about a quarter million residents, and fewer still in its urban center. Even among this small audience, only a minority possessed what we would today call literacy: the ability both to read and write fluently. The scarcity of objective data on the topic—much of which derives from the hints in Greek drama discussed above—has led to estimates of Athenian literacy ranging from a few percent to “near-universal.” The consensus falls in the range of 5 to 10 percent for the entire population of Attica, but this estimate implies a much higher rate among male citizens, perhaps around 25 to 50 percent. Only among the Athenian elite was literacy near-universal.45

This should not surprise us. Although the Greeks had solved many of the abstract hindrances to literacy that plagued their ancient predecessors, they had not overcome all of them. One in particular that persisted was scriptura continua—a nearly total lack of punctuation, and even of word, sentence, and paragraph breaks. Further, the Greeks had made no progress in overcoming the mechanical hindrances to literacy: the difficulty of working in stone, the expense of papyrus, the absence of the printing press, and the lack of universal education. In the early fifth century BC, a roll of papyrus, consisting of about twenty sheets, cost between one and three drachmas—that is, one to three days’ wages for a semiskilled worker.

Of all the world’s peoples, the Greeks may have written on the widest range of materials: not only on papyrus, but also on gold, silver, bronze, pots and pot fragments, wood, wax, and even thin sheets of lead, which, since they could be easily folded and placed in coffins, were used to transmit curses to the underworld.46

In the predominantly oral societies of the ancient world, the reader declaimed aloud to the group; not until the early modern period, centuries after the invention of the printing press, would large numbers of people acquire the modern habit of rapid silent reading. Still, by the standards of the ancient world, the Greeks had wrought a revolution in communication; the new literacy brought with it new philosophical and logical constructs, and a new concept of theatrical performance to boot.

The advance of literacy in Greece was accompanied by a revolution in politics. Sometime around the middle of the seventh century BC, Athens began its long, gradual, and occasionally stuttering march toward ever-greater diffusion of political power among its population. By around 650 BC, the leading families of Athens had amalgamated the city and surrounding countryside, collectively known as Attica, into a cohesive city-state. Initially, each year these aristocrats elected a single chief magistrate—the archon. Next, the archonship was divided into three offices—one each for political, military, and religious affairs. Not long after, the Athenians added six more archons to record the law for all citizens to read; thus it is likely that all archons had to be literate. (Confusingly, classicists commonly refer to the “political,” or chief, archon as the archon; henceforth in this text, the singular form of this word refers to this particular official.)

As these nine aristocrats rotated out of office each year, they joined the real locus of power in early Athens, the Areopagus (roughly, the high court), for life. Although all free citizens could participate in the Assembly, it held little power. In actuality, only a few families controlled the political process, largely through the Areopagus, and this leadership exerted power in no small part through one preferred instrument: expulsion, or the threat of expulsion, from the city.

Upon being expelled, the losing party took up exile in a neighboring city and immediately began to plot, with both domestic and foreign allies, his return. Thereupon followed a never-ending cycle in which the expelled replaced the expellers. By the late seventh century BC, Athenians began to weary of this instability, and they invested the archon Draco with the authority to devise a written legal code to mitigate the turmoil. His extraordinarily strict system of laws (hence the word “draconian”), alas, did not stop the expulsions.47

In the early sixth century BC, Athens gave another archon, Solon, much the same mandate. His laws also failed to stop the expulsions, but by means of these written laws, for the first time accessible to an increasing number of literate citizens, Athens got its first real democratic reforms.

Solon’s reforms gave citizens the right to prosecute on behalf of the public good—the grapheˉ. Needless to say, while any citizen could exercise this privilege, it required an understanding of the written law—the very term grapheˉ, which derives from the Greek verb “to write,” embodies the link between widespread literacy and political empowerment.

In preliterate societies, the magistrate himself embodied the law, and in subsequent ancient societies in which a small elite could read and interpret the written code, the balance of power still heavily favored the person in the chamber able to decode the tablets. When Athenian litigants began to wield the power of their simple alphabet, the rights of ordinary citizens expanded greatly.

In the seventh and sixth centuries BC, then, Athens slowly acquired institutions that allowed “ordinary” citizens the tools with which to wield political power. Nonetheless, the expulsions continued, and power remained highly concentrated among a continually shifting, unstable mix of rival elites. After a long series of coups, expulsions, and exile-driven countercoups, one family, the Alcmaeonids, wound up in control around 508 BC.48 This aristocratic family, an ancient version of the Kennedys, produced generations of politicians and soldiers, most famously Pericles. They wisely allied themselves with the middle classes and enacted a series of laws, known as the “Cleisthenic reforms” after the Alcmaeonid, Cleisthenes, who devised them. These changes produced the commonly recognized features of the famous Athenian democracy, and they did so by, for the first time, codifying and institutionalizing exile into two separate procedures: ostracism and expulsion.

The first process, ostracism, required no well-defined offending act. Loosely speaking, its most common rationale seemed to involve the target’s “growing too big for his britches,” and ostracism may even have been considered, at least in some quarters, an honor. Each winter, the Assembly held a vote that determined if an ostracism would be held. If that vote passed, then the Assembly decided two months later who would be ostracized. If, and only if, a quorum of six thousand was present for the second vote, the “winner” was expelled for ten years, following which he came back with full privileges; in the interim, his property was held in trust.49

The Athenians tended to ostracize only their best and brightest. For example, when the Athenian Hyperbolus was ostracized in 415 BC, contemporary observers scoffed that he was not worthy of the honor, since he did not belong to the landed class.50 Citizens wrote the names of candidates for ostracism on the ostraca described in the Introduction; consequently, archaeologists have acquired a compendium of those considered for the process, and the list reads like a Who’s Who of Athenian politics.

Among those actually ostracized were Thucydides, for falling short during command of a naval campaign during the Peloponnesian War; and Aristides, who was cast out around 482 BC after valiantly serving the city in multiple capacities, most notably at Marathon. According to Plutarch, the following occurred at Aristides’s ostracism:

As the voters were inscribing their ostraca, it is said that an unlettered and utterly boorish fellow handed his ostracon to Aristides, whom he took to be one of the ordinary crowd, and asked him to write Aristides on it. He, astonished, asked the man what possible harm Aristides had done him. “None whatever,” was the answer, “I do not even know the fellow, but I am tired of hearing him everywhere called ‘the just.’”51

By requiring six thousand ballots—a fair percentage of citizens—the ostracism process depended upon widespread, if rudimentary, literacy among at least a substantial minority of citizens. Were all, or even a majority, of this quorum able to read and write at a basic level? The thousands of ostraca in the archaeological record do cast some doubt on the notion of widespread Athenian literacy. One archaeologist found 191 ostraca inscribed with Themistocles’ name and concluded that they had been written by just fifteen people, the clear implication being that they had been premanufactured.52

Were ostraca premanufactured because illiterate citizens required them for “ballot-stuffing” campaigns, or merely because even literate citizens appreciated the convenience of instant ballots? All things considered, it seems unlikely that this institution could have functioned as smoothly as it did in a society in which only a few literate citizens were able to make informed decisions about whom to cast out, and consequently would have been easily manipulated by the wealthy and powerful.

Archaeologist Eugene Vanderpool imagined the technical process surrounding an ostracism vote as follows:

The party heelers assigned the job of collecting sherds very sensibly decided to go to the source—the potter’s shop—and get them from his dump of broken or discarded pots. . . . Other heelers were summoned, were shown the pile of sherds and were told to sit down and write the name of Themistocles on as many pieces as they could. On Ostracism Day each took as many sherds as he could conveniently carry, went down to the Agora and circulated among the crowds, handing out his ready-made ostraca to any who wanted one.53

Such finds demonstrate the telltale signs of widespread but imperfect literacy, such as nearly constant variations in and errors of spelling and even in the direction of writing. In addition, ostraca writers frequently added extraneous comments, such as the reasons for the vote or merely some variation of “Out with him!”

Well-defined high crimes—corruption and treason—could be answered with permanent expulsion, confiscation of property, and execution, but this, too, required formal judicial criminal proceedings. Athenian juries consisted of several hundred citizens each, thus preventing the elite from meting out arbitrary punishment.

Aristotle describes in some detail the voting procedure for civil and criminal cases: Officials assigned each juror a colored staff so that he could find his way to the proper court. Officials limited the pleadings “by the clock,” that is, a water clock. In a civil case involving more than five thousand drachmas, each side was allowed two speeches: ten gallons of water for the first, and three for the last; the less money involved, the less water allotted.

At the conclusion of each case, the jurors’ staffs were exchanged for two bronze disks: one pierced with a hollow stem, signifying a vote for the plaintiff, the other pierced with a solid stem, signifying a vote for the defendant. Carefully keeping his hand closed to ensure secrecy, the juror then placed the “active” vote in a brass urn and the “discarded” vote in a wooden urn. In addition, each urn was carefully crafted so that only one disk could be inserted at a time. After the juror had disposed of his two disks, he received in return a brass disk on which the number three was inscribed, his voucher for the three obol (one-half drachma) jury fee.54

Aristophanes’ Wasps, a comedy focused largely on the Athenian jury system, makes clear the centrality of literacy in that system. Of the enthusiastic juror Philocleon, his slave complains, “He is a merciless judge, never failing to draw the convicting line and return home with his nails full of wax [from writing on wax-covered tablets] like a bumble-bee.”55 (The Michael Moore of his day, Aristophanes satirized the ease with which the jury and assembly could be influenced by demagogues, his favorite target being the lowborn, real-world demagogue Cleon: hence the name of Wasps’ protagonist, Philocleon.)

Unsurprisingly, playwrights often found themselves legal targets; Cleon took Aristophanes to court, just as two generations before Aeschylus was prosecuted for supposedly revealing religious secrets onstage. In both cases, the playwrights’ literary skills secured their successful defense.56

Ostracism and expulsion, both democracy-based and literacy-dependent processes, became rule-bound, legitimate, and infrequent; the overwhelming majority of ostracisms occurred in the half century following the Cleisthenic reforms, and almost none in the last century of Athens’ independent existence. Today we realize that one bedrock principle of democracy is the limitation of official power; the mere presence of formalized writing-based institutions in Athens meant that the rich and powerful could no longer embroil the city in an endless cycle of mass expulsion and civil war.

Figure 2-4. Bronze jury ballots; the hollow stemmed ballot on the far left signifies a vote for the plaintiff; the solid stemmed ones, a vote for the defendant.

The Cleisthenic reforms, besides taming the scourge of indiscriminate expulsion, started Athens down a road of increasing democratization that did not cease until the conquests of Alexander two centuries later. These reforms increased the number of “tribes” from four to ten, each of which elected fifty members of the Council (Boule). The four original tribes may have possessed a kinship/hereditary character, but the Cleisthenic reforms almost certainly intended the ten new ones to function only as civic units, much like modern political wards. The Boule prepared the issues to be addressed in the Assembly, which ultimately decided the important military, legal, and economic business of the state. Finally, in the middle fifth century BC, the Areopagus, which was dominated by the aristocracy, was stripped of all but its ceremonial power. The Assembly and Boule were at least theoretically open to all citizens, and increasing literacy translated into more public participation and democratization.

The tribes also elected by ballot archons, strategoi, and the festival commissioners, all of whom needed highly specific skill sets for their critical posts. The elected position of strategos carried with it political as well as military power, since, unlike other officials, the most successful commanders could serve numerous terms. Consequently, the ranks of the strategoi include the most famous names in Greek history: Aristides, Themistocles, Thucydides, Pericles, and Demosthenes. For all practical purposes, “civilian leadership” in the modern sense did not exist in Athens; after the Cleisthenic reforms, virtually all of its great politicians served multiple terms as strategoi. Such prominence, in turn, almost inevitably made them targets for punishment at the hands of an increasingly literate public.

Every year the tribes also selected six thousand citizens by lot for jury duty. The juries were then broken into panels of several hundred. Lots were also drawn to assign ordinary citizens to serve in the mundane, technocratic machinery of government. Each year the ten tribes randomly chose one of their members to serve on the Commission for Public Contracts, which, among its other tasks, kept track of taxes, executed court-ordered confiscations of property, and leased out public mines.57

Athens also chose by lot “the Eleven,” who oversaw the arrest of prisoners and—when these sentences were ordered by the courts—their jailing and execution. State slaves, who during the fifth and fourth centuries BC mainly consisted of around three hundred Scythian archers, performed the actual dirty work under the Eleven’s orders.

Each tribe also selected, in rotation and by lot, a city commissioner whose duty was

to see that female flute- and harp- and lute-players are not hired at more than two drachmas, and if more than one person is anxious to hire the same girl, they cast lots and hire her out to the person to whom the lot falls. They also provide that no collector of sewage shall shoot any of his sewage within ten stradia of the walls. They prevent people from blocking up the streets by building, or stretching barriers across them, or making drain-pipes in mid-air with a discharge into the street, or having doors which open outwards. They also remove the corpses of those who die in the streets, for which purpose they have a body of state slaves assigned to them.58

The all-inclusive Assembly, which met about forty days per year, decided the key policy and military issues. Someone with the oratorical skill to sway opinion—a rheˉtoˉr, literally, “talker”—wielded the greatest power. (Contrariwise, the Athenians expressed their disdain for someone who remained silent in the Assembly through the name used to describe him: idioˉteˉs.) Debate, and particularly procedural maneuvering, carried real risks; any Assembly member who violated these rules could be indicted for the lapse, the most common of which was known as a grapheˉ paranomoˉm, the making of an illegal proposal.

A term as a strategos or an archon provided the vital debating and parliamentary skills necessary to wield influence in the Assembly. Obviously, while no literacy requirement is known for any position, the ability to read and interpret laws, to understand accounts, and to follow agendas would prove essential to a citizen to wield influence in such a meritocratic environment.59

The epic life of one of the greatest of Greek heroes, the strategos Themistocles, provides a lens through which to understand the nexus of citizenship, democratic politics, and literacy in ancient Athens.

Probably born to upper-class parents around 524 BC, Themistocles was a clever, impetuous youth who forsook the musical instruments and idleness of his peers to burnish his rhetorical skills. When taunted by his more aristocratic classmates about his lack of musical ability, he replied that he would rather use his hands to make a small city great than to tune a lyre or handle a harp.60 Which is exactly what he did.

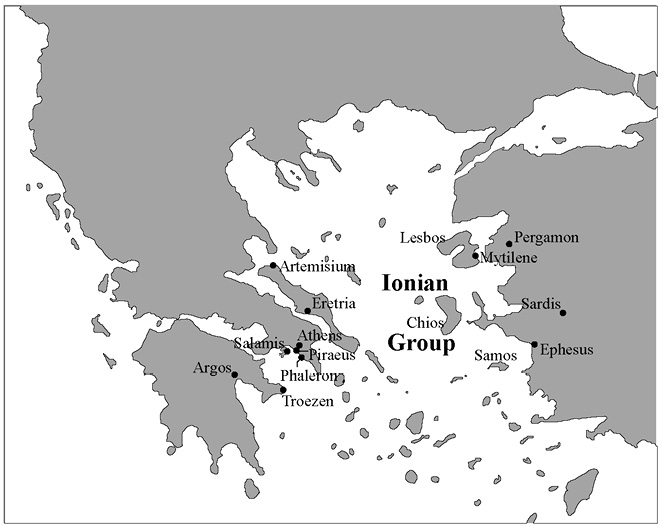

Recall the story of Oroetes, Polycrates, and Darius. Along with the capture of Sardis by Cyrus in the sixth century BC, the Persians had subjugated the Greek city-states on the mainland of Asia Minor (western Turkey) and on the islands lying off it. The lonians, a linguistically and culturally homogeneous group of Greeks who inhabited many of these Persian-occupied city-states, revolted around 499 BC. Athens, also founded by Ionians, aided and abetted its brethren’s ultimately unsuccessful cause, and thereby provoked the massive Persian invasion of mainland Greece several years later. This titanic clash of civilizations—the Persian Wars—engulfed the entire Greek world.

After the Ionian Revolt finally collapsed in 494 BC, the Persians sent emissaries to the Greek city-states demanding gifts of earth and water, signifying submission. The Athenians buried the Persian messengers alive in a pit—the punishment for common criminals. The Spartans went one better and took their Persians to a well, told them that this was the best place to find earth and water, and then tossed them into it.61 Not long after, in 493–492 BC, Themistocles ascended to the high office of archon, just after he attained the age of thirty—the qualifying age for the post. Foreseeing the approaching Persian hurricane, he moved the main port of Athens from Phaleron Bay to more easily protected Piraeus.

Figure 2-5. Ancient Greece in the classical period (ca. 500 BC).

The Persians invaded the mainland in 490 BC and made fast work of the city-state of Eretria, which, like Athens, had sent warships and troops in support of the Ionian Revolt. Darius burned its temples, carried its populace off into slavery, and then set his sights on Athens, choosing the plain of Marathon—which as every modern running enthusiast knows, is about twenty-six miles east of the city—as his beachhead for its conquest.

Miltiades, the Athenian commander at Marathon, executed a brilliant tactical retreat in the center of his battle line, which allowed his forces to encircle and defeat the Persians. Themistocles, who had participated in the battle in a subordinate position, returned to Athens restless and uneasy. He was restless because he had achieved too little glory at Marathon. According to Plutarch, “the generalship of Miltiades was in everybody’s mouth,” but subsequent events demonstrated the fickleness of Athenian politics. Soon after Marathon, Miltiades led an unsuccessful mission against Paros, an island city-state which had supported the Persians by sending them a warship. For this failure, he was brought up on charges of “deceiving the people” and fined fifty talents—about three thousand pounds—of silver.

Themistocles was uneasy because he also understood, as many of his countrymen did not, that the Battle of Marathon had not ended the Persian Wars—not by a long shot. So distraught was Themistocles that he refused even to drink and carouse with friends.

In 480 BC, the Persians returned, as Themistocles had known they would. The Greeks could do little against the Persians’ massive onslaught save for a few delaying actions: the disastrous slaughter of the cream of Sparta’s troops at Thermopylae, and an equally fruitless stand by the Athenian fleet, now under the command of Themistocles, at nearby Artemisium. The Greeks repaired south, leaving their homeland defenseless before the victorious barbarians from the east.

What Athens did next is vividly described by a marble inscription recently found in a coffeehouse in the city of Troezen, in the northeast Peloponnese, across the Saronic Gulf from the city:

This decree was passed by the [Council] and by the [Asscmbly]; Themistocles, the son of Neocles, of Phrearrhioi, proposed it; The city is to be entrusted to [the gods]. . . . Children and women are to be taken to Troezen. . . . Old men and [slaves] are to be taken to Salamis; treasurers and priestesses are to remain on the Acropolis watching over the things of the gods; all other Athenians and foreigners of military age are to embark on two hundred ships, which have been made ready, and ward off the foreign enemy for the sake of freedom, both their own and that of the other Greeks.62

Themistocles realized that the Greeks had only one chance in the face of nearly certain doom: avoid a land battle with the vastly superior army of Persia and instead draw its fleet into the narrow waters between the Attic mainland and the island of Salamis, where the heavier but less maneuverable Greek ships held the advantage. Indeed, Themistocles triumphed in just this way: he persuaded Athens’ reluctant allies to join him, tricked the Persians into fighting at Salamis, and prevailed in a naval battle that gave maximum advantage to the ponderous but lethal Greek triremes.

He returned to Athens with the glory that had eluded him at Marathon, and he was lionized even more in Sparta than in his native city. After Salamis, the Spartans awarded Themistocles olive branches, and they also bestowed upon him a chariot, “the finest in Sparta.” He was then escorted back to the Athenian frontier by three hundred handpicked hoplites—this number being symbolic of their number fallen at Thermopylae—“the only person we know of who ever received the honor of an escort from the Spartans,” according to Herodotus.63

In the afterglow of Salamis, Themistocles went on to hold many important Athenian offices, which enabled him to complete the fortification of both Athens and Piraeus. He intentionally concealed these works from the Spartans, thus angering them. An even more potent hindrance to his career was the perverse logic of Athenian politics, which dictated that his triumph only made his countrymen fearful of his growing power and influence. In the end, it would be this growing Spartan animosity, combined with the Athenian mistrust of successful politicians, that ended his political career at Athens.

Around this time, Pausanias, a traitorous Spartan general, and Themistocles spoke or at least wrote to each other. The Spartans used the communication between the two generals to impugn Themistocles’ loyalty to the Greek cause, but no evidence ever surfaced that the two had actually conspired against their homelands. Sometime around 471 BC, nearly a decade after the naval battle at Salamis, domestic opponents of Themistocles seized upon these Spartan fabrications to have him ostracized.

Our slandered hero chose nearby Argos as his place of refuge. At this point Pausanias supposedly asked Themistocles to join him in his collusion with the Persians: Themistocles refused, but kept the episode secret. After the death of Pausanias, the Spartans came across letters between the two generals and demanded that Themistocles be tried for treason, a capital offense that by Greek custom would be adjudicated by a congress of several city-states.

Themistocles understood that he could not obtain a fair trial in such circumstances, and so embarked on an odyssey that took him across the length and breadth of Greece. Finding no refuge there, he eventually obtained shelter in the service of Xerxes’s successor, his son Artaxerxes I. Themistocles’ flight to Susa was certainly a calculated risk; initially, given his role at Salamis, the Persians did not exactly greet him with open arms. His political and intellectual skills, nonetheless, enabled him to learn Persian late in life and gain such influence at court that Artaxerxes made him governor of several satraps in Asia Minor; subsequently, upon being ordered to attack the Greek mainland, he supposedly committed suicide with a draught of bull’s blood.64

It is remarkable that the Athenians cast out, on what seems to be the flimsiest of evidence, the man who had saved Athens, and, arguably, Western civilization as well, to say nothing of other heroes, such as Miltiades, the victor at Marathon. Amazingly, Athens ostracized, or at least attempted to ostracize, nearly all its greatest leaders.

Ostracism puzzles and at times outrages Western readers; much of the wariness of the American founding fathers of direct participatory democracy originates from this ancient institution. John Adams, for example, wrote of ostracism:

History nowhere furnishes so frank a confession of the people themselves, of their own infirmities and unfitness for managing the executive branch of government, or an unbalanced share of the legislature, as this institution [ostracism]. . . . What more melancholy spectacle can be conceived even in imagination, than that inconstancy which erects statues to a patriot or a hero one year, banishes him the next, and the third erects fresh statues to his memory?65

Adams’ disdain aside, the above history demonstrates how the Athenian combination of ostracism, literacy, and unique participatory system of government lay at the heart of its democracy.

Modern readers might well wonder why anyone of ability and ambition bothered with Athenian politics, given the punishments meted out for even the smallest of errors—actual, perceived, or simply manufactured by opponents. During the fourth century BC alone, Athens prosecuted twenty-seven strategoi for malfeasance; four were executed, five fled under sentence of death, and others were expelled or heavily fined.66 Even riskier than generalship was leading a criminal prosecution, a role, open to any citizen, that painted a virtual legal bull’s-eye on one’s back.

Athenians participated in the process for one simple reason: timeˉ (honor). Athenian citizenship, generally open only to those who could claim it from both parents, constituted one of the most sought-after commodities in the ancient world. Athenians measured each other’s status not so much in terms of silver or land, but rather according to their performance in the Assembly and on the battlefield; that a citizen risked life and treasure in the process mattered less than the esteem of the polis. The citizen of any Greek city-state best expressed timeˉ, of course, by falling in battle for his polis.

Thus, for almost two hundred years, two features, both of which required widespread literacy, lay at the center of Athenian democracy: widespread citizen officeholding that would be impossible in a modern nation-state and the peculiar institutions of ostracism and expulsion. These latter processes served as safety valves that prevented the undue accumulation of power by removing from the city-state those who might threaten its democracy. It is difficult to imagine officeholders randomly drawn from a largely illiterate populace maintaining a more or less orderly city-state for the better part of two centuries, and it is equally difficult to imagine the processes of ostracism and judicial expulsion functioning smoothly in an illiterate environment.

Although America’s founding fathers did not think much of Athenian “radical democracy,” and thought particularly ill of ostracism, even cursory consideration of the city-state’s history shows that its politics grew ever more stable and inclusive between the Cleisthenic reforms of the late sixth century BC and the city’s conquest by the Macedonians in the late fourth.67 True, in 411 BC, and again in 404 BC, tyrannical Athenian regimes captured power, the reign of 404 BC proving particularly murderous. Both episodes, however, occurred during the extreme geopolitical stress of the Peloponnesian War. Both oligarchic interludes proved remarkably brief, and the democratic institutions of Athens, and its respect for the rule of law, seemed to grow continuously stronger right up to the moment that Macedonia’s army overpowered the city and overturned its constitution.

To its very end, Athenian democracy remained robust, destroyed not from within but by foreign military force. Ostracism, rather than being a blot on the political life of Athens, prevented the undue accumulation of power in a few hands and constituted the cement that held its democracy together even as it paradoxically fell into disuse because of its own success—a cement whose primary ingredient was widespread literacy.

Likewise, without a critical mass of literate citizens, chosen at random to perform key legislative, judicial, and especially executive duties, it is hard to imagine Athens surviving for very long, let alone rising to the pinnacle of the ancient Greek world. Similarly, those who wished to exert influence in the Assembly and on the battlefield had, of necessity, to acquire literacy and deploy it with skill.

By contrast, in oligarchic Sparta, few read or wrote, as evidenced not only by the frequent observations of Spartan illiteracy by the admittedly chauvinistic Athenians, but also by the scarcity of inscriptions in the southern Peloponnese. Greek tradition suggests that the Spartans forbade the writing down of their laws, and that only the elite—their two kings, five ephors (judges), diplomats, and high military commanders—possessed the literacy demanded by their roles.

Sparta’s social structure probably contributed in no small part to this distrust of the written word. Sparta, the largest city-state in Greece, attained its size and prominence through the conquest of the Messenians, who inhabited most of the southern Peloponnesian peninsula. The Spartans enslaved this unfortunate people, who evolved into a vast underclass of so-called helots. Since they greatly outnumbered the relatively small number of Spartan citizens—by some estimates, the ratio was in excess of ten to one—the helots had to be brutally suppressed by means of the krypteia. This term had two meanings: the first, a secret police charged with keeping the helots in line; and the second, an annual rite of passage in which young Spartans went out and slaughtered them.

Fear of helot rebellion held the city-state’s constant attention, and so the Spartans restricted literacy, lest the power and knowledge it conferred wind up in the wrong hands. The Spartan distrust of literacy entailed denying it not only to the helots, but to the citizen rank and file as well; thus did democracy fail to flourish in the Peloponnese.68

Curiously, though official Athens looked with favor upon individual literacy, it seemed indifferent to detailed written records, and this, paradoxically, may have contributed to the city-state’s robust democratic institutions. Not until the middle fifth century BC did the city-state establish a central records repository, the Metroon, which served mainly to store laws, treaties, and decisions of the Assembly, and other public documents. Athens largely ignored private data. For example, citizens did not publicly record land sales or surveys, but rather demarcated their property boundaries with simply inscribed stone monuments.

And therein lies the last piece of the puzzle of ancient Greek democratic exceptionalism: unlike the despotic empires of Mesopotamia and Egypt, the “Athenian empire” did not maintain an army of scribes and bureaucrats to deploy the awesome power of the written record to organize and control empires and millions. Instead, the Athenians staffed their offices and ministries with an ever-changing retinue of farmers, merchants, and artisans, most of whom had to be literate. Further, ordinary Athenians could not be cowed by the “magic of the written word” characteristic of illiterate societies.

What was lost in technical efficiency with this less than optimal bureaucratic manpower was more than offset by the freedom from tyranny it afforded ordinary citizens and the avoidance of the institutional sclerosis and corruption characteristic of both ancient and modern scribal elites.

The apparent unwillingness of the classic-era Greek city-states to deploy the full power of the written record ended with Alexander’s conquests in 334–323 BC, which resulted in several large successor states following his death: the Seleucid Empire in the Middle East and the Pergamon, Macedonian, and Ptolemaic kingdoms in Asia Minor, Greece, and Egypt, respectively.

The Greek/Egyptian kingdom founded by Alexander’s lieutenant Ptolemy provides historians with the world’s richest source of papyrus records for at least four reasons. First, Egypt produced nearly all of the world’s papyrus. Second, because of the country’s dry climate, its papyrus records were preserved better than those from any other ancient civilization. Third, his heirs, the Ptolemies, reigned less than two-and-a-half millennia ago, well within the survivability of papyrus records under optimal conditions. Fourth, the Ptolemies, like their Egyptian and Mesopotamian predecessors, fully grasped the value of written records for command and control.