Chapter One

Atrocious Lima

'This is my company card,' said glamorous Rosa, the car-hire woman at Lima airport. We noticed the Playboy bunny badge on her lapel, if you have any problems while you are in Peru you can telephone.'

She smiled, hesitated ... 'And this is my home number. I would like to service you personally when you return. Please contact me' — she winked, in case Ian had missed the point - 'big boy ...'

Ian, fresh-faced, sharply dressed and newly graduated in geography from Sheffield Polytechnic, had only fifteen hours ago detached himself from a passionate farewell kiss with his latest girlfriend, at London's Heathrow airport. He was in no mood for a fling with a Peruvian bunny-girl.

'Or any of your friends ...' Rosa added. She glanced at Mick, John and me.

John glanced shyly down, avoiding her eyes and returning to his book, the book he carried with him everywhere. It was a bird watchers' manual, and he had been committing the chapter on torrent ducks to memory. These ducks, he had explained during the long flight, 'are specially streamlined to shoot the rapids, you know - spend all day shooting up and diving down. Ever seen one? I'd give anything to! Lots in the Andes.'

John had celebrated his last evening with his young wife by taking her to sit on some rocks near a hole in the ground to watch in case badgers came out. By z a.m. none had, and he had returned to pack, leaving her with a flask of cocoa to continue her observations alone. Rosa had little chance here.

And Mick? He had already telephoned his wife twice: once (at Heathrow) to ask about some unlabelled pills and liniments from his huge collection, and once (during a stopover in Bogota, Colombia) to remind her to water the tomatoes. He was a church warden at his local village church. Here, too, Rosa's chances were slim.

We thought of her, later, in Lima's Museum of Erotic Art (adults

Inca-Kola

only): a collection of ancient Inca sculptures and carvings, mostly of men and women coupled in the dog position. Rosa would have been more inventive.

We took from her the keys to the little Japanese car we had hired, and set out.

Lima is an atrocity. Ankle-deep in urine and political graffiti, the old Lima rises from the middle of the largest expanse of wet corrugated iron in the southern hemisphere: the new Lima.

'Ah! Que lindas las tardes de Lima!' ('How lovely those Liman afternoons!') runs the old Spanish song, recalling an elegant past, long faded now. The old Lima died, our hotelier told us, 'when the slum-people came'.

But the old Lima is still discernible: the colonnades and avenues that have survived a series of horrific earthquakes to stand, cracked and peeling monuments to their imperial past.

At the core of the city, then, lies the decaying hulk of a great colonial shipwreck. In flaking baroque these relics gaze, stained and weary, over the tin and concrete and electric wires. They are waiting for the next earthquake to do the decent thing.

'drink inca-kola !' screamed the neon through the filthy air as we piloted our tiny car between the pot-holes and dogs' corpses which adorn the Avenida Elmer Faucett leading into town. The foggy grey dawn turned into a grey morning drizzle, a grey afternoon and a damp grey twilight.

So it was until we quit, so it was when we returned, and so it remains all winter. The Pacific coast lies beneath a great bank of cloud, permanent and solid, its top surface basking flat and still in the sun, pierced by the Andes which emerge as from a sea. Its underbelly heaves gently up and down, loosing a thin and intermittent drizzle over a sombre city. It never quite rains and it never quite shines.

The rich escape for weekends up the side of the mountains where you climb into the sunlight and look out over a white ocean of cloud. The poor are consigned to Lima. The place is purgatory.

Lima's traffic must be seen to be believed. It is a war between cars and pedestrians in which there are no rules, and many casualties on both sides. Motorists prefer to drive on the right but it is only a tendency. A bare majority of cars have headlights, far fewer have tail-lights, and there is a general amnesty on traffic-lights. No signals at all are used, in any circumstances.

Into this assault course we were immediately plunged. John took the wheel. He showed a flair and ingenuity which no one had suspected. A man with a passion for wild birds and flowers and who complains

Atrocious Lima

noisily about the uselessness of foreigners, seemed the last person to dive happily into Lima's traffic. Once - only once - he complained, 'Bloody Latins!' - as a taxi came at us head-on, driving on the wrong side of the road to avoid pot-holes. Then a dead animal (we did not have time to see what kind) loomed into vision, blocking our path. John did not hesitate, nor did he complain. Without touching the brakes or making any kind of a signal he swerved straight over the carriageway, dodged an oncoming bus and - with a triumphant blast of the horn -returned to the right side, downstream of the corpse.

There was a jaw-clenched silence in our car. 'I think I could learn to enjoy this,' John said. After that there was no stopping him.

One thing saved us from real tragedy: cars in Peru do not, in fact, move very fast. They can't. Go to any scrapyard in Europe and command the wrecks to rise like Lazarus from the slab: you will have launched a fleet of the finest and newest that Lima has to offer! Chevrolets that are barely post-war; Dodge pick-ups that are not; boots and bonnets missing, windscreens entirely absent or with peep-holes punched through the shattered glass, chassis twisted and steering awry, they stagger honking along the road, seldom firing on all cylinders, and belching smoke. But slowly. Lima's traffic is a sort of limping mayhem.

Through it, we were heading for a hotel whose address we had been given in England. The best route appeared to be across the centre of Lima, so that was our first destination. 'We could do some sightseeing while we drive,' said the optimistic Ian. Soon, John was traversing one of Lima's widest highways, across five lanes of angry buses.

These buses must be seen to be believed: symphonies in blistered rubber, ripped metal and smashed glass, each with its own name - Jesus, for instance, or Fifi - painted above the windscreen. They compete vigorously for custom. Packed to bursting they will dive across each other's paths to pick up new passengers.

Their competitors up-market are the colectivos, battered little win-dowless vans which ply a set route for a set fare. Up-market of the colectivos are the taxis. Some of these are actually identifiable as taxis. Others are simply private motorists with time spare to make a quick buck. Never wink, blink or twitch a finger on the streets of Lima, lest the nearest car plunge for you in the hope of negotiating a fare.

We would have done better to travel that way. That much became clear when we reached the centre.

It is hard to say at what point the street John was driving down became the Central Market, and ceased to be a street, for it all seems a blur now. Nor is it clear how we got between the peanut barrow and the record stall, though we smelt the roasting nuts and heard the needle jump. Memories of the clothes and dressmaking section of the market are confused and our drive through the religious and devotional kiosks

Inca-Kola

was a nightmare only half-remembered. All we know is that - often tempted to ditch the car - we were impelled onward by the thought that it must surely end, somewhere. And by the fact that nobody outside seemed in the least taken aback to see us.

The old Indian lady in bowler hat and acres of pink skirts, whose roaring kerosene stove almost set fire to our front offside tyre, seemed surprised only that we continued without buying any of her fried sausages. The money-changer whose calculations we almost upset called out his rates as we passed. It was like driving through Woolworths on a Saturday morning without so much as a raised eyebrow from customers or staff.

In the end we did reach our hotel. Lima was best explored on foot.

Chapter Two

Skulls, Feathers and Dollars

La Alameda was a small, pleasantly quiet hotel, in a place of fading elegance called Miraflores, which means Look-at-the-flowers. This had once been the real Lima, but no more.

The real Lima lay some way off. But, in Miraflores, never out of mind: to keep the real Lima at bay, there were security guards everywhere. Down an avenue of torn and dying trees ran the toxic life-blood that even the healthy parts of a body must share with the diseased: a stream of broken vehicles belching filthy smoke and carrying, to the doorsteps of the rich, the poor men, beggar-men and thieves from the poorer quarters.

These we needed to see, but first money had to be changed. Our experience so far with South American currency exchange had been slight, and bizarre. Needing a little local currency during the stopover in Bogota we had been directed to a hawker selling condoms and pistachio nuts. He was also the money-changer.

In Peru the position was no less strange, but it took on a manic quality. Peruvians were desperate for dollars. Their own currency was inflating so fast that savings lost their value almost as you watched. The national banks' interest rates were 48 per cent but inflation was more than 100 per cent, so - as one shopkeeper told us - the best thing to do with your money was buy dollars, or gems, 'or alcohol'.

The government, in a futile attempt to keep money in the country, had fixed the international value of their currency artificially high (so that foreigners would have to bring more dollars into Peru and get fewer Peruvian intis in exchange). To stop their own citizens from switching out of local currency, the government was limiting the amount they were permitted to change to a tiny sum.

Of course the result was a black market. We never once saw or heard of any foreigner changing money in a bank. Peruvians would offer you a huge premium to change it with them, illegally, on the street. Bureaux

Inca-Kola

de change had just been closed and locked, by law, but on the street you could get twice the official rate for a dollar.

The money trade flourished in Miraflores. You were importuned on every corner by little men clicking pocket-calculators at you. The police seemed to turn a blind eye.

The game was to find the best rate. Competition between touts was fierce; and we were warned to watch out for cheats who offered the old, worthless notes to unsuspecting foreigners. We decided to split up and try our chances independently.

Ian failed spectacularly. Standing outside the Centro Pediatrico Higgins he saw a well-dressed, elderly gentleman, in cravat and sunglasses, staring significantly at passers-by. Ian stopped in his tracks and engaged eye-contact.

'You want some business?' said the man, in broken English. Ian nodded enthusiastically. l Bueno. How much?'

'A hundred and fifty dollars,' replied Ian, thinking he might as well change plenty.

'Que? A hundred and fifty dollars? You think just because you blond boy, I pay a hundred and fifty dollars? I get fucky-fucky with much cheap boys. Dollars no. lntis. y

Ian scarpered.

John got closer. A young chap with alcohol on his breath, dressed Peruvian-cool (fake UCal T-shirt and ski shades - it was night) tugged his sleeve. He offered a rate markedly more favourable than we had been told to expect.

At the last minute, John spotted red numbers on the notes he was being handed. These, we had been warned, were the duds. Mick was nearby and John called to him. The rascal grinned and sauntered off. He didn't even run.

Still, Mick got a good rate from a little oriental-looking tout. The other money-changers called him 'Chino'; they flocked around as soon as we joined Mick's negotiations and started trying to outbid - first Chino, then each other. Eventually we four were able to stand back, hiding our amusement, while Chino and his competitors bid each other downwards in a furious private auction. Once the bid reached some kind of floor we accepted the best - still Chino's - and changed all we needed.

En route, triumphantly, home, John suggested a meal. He nipped up some stairs to inspect the first (as it turned out, the only) Hindu Peruvian vegetarian restaurant we were to encounter. He returned unimpressed: 'Asian waiters. Peruvians eating yoghurt.' We moved on.

The place we settled on proved adequate, though their menu had been eccentrically translated and none of us was tempted by 'cattle

Skulls, Feathers and Dollars

consomme'. Only gradually does one come to realize there is really only one menu in Peru; and that, without rice, potatoes, scraggy beef and fried eggs - all seared by fiery red pepper sauce - most restaurants would close. First courses are no more varied: avocado stuffed with egg-and-potato salad (good) and chicken-claw soup predominate; but on the coast ceviche, which is raw fish marinated in lime juice, is served everywhere. Coffee is vile, and there is no milk anywhere.

One of us tried the ceviche. It tasted better than it sounded. We tramped wearily back to the hotel, past the gates of a huge cinema whose lights trailed (translated), 'the monster club, a collection

OF RICH VAMPIRES, SNAKE MEN AND WOLF MEN. EVERY KIND OF CREATURE WHO LIKES ROCK MUSIC. LUMINOUS PHANTOMS!'

Where the London barrow-boy may deal in flowers, bananas or postcards, his equivalent in Lima hawks volumes on molecular physics, Chilean maritime law or the Bolivian constitution. These nestle side by side with Ingrid Bergman's memoirs and the Marxist interpretation of Inca imperialism. Nowhere can so many or such varied book stalls, book barrows or book carts ply their trade in such unlikely streets. Dogs, beggars and prostitutes pick their way through this outdoor library, as comfortable with anthologies of pictures of girls' bottoms, on one side, as they are oblivious of Plato and Wittgenstein on the other.

As we jostled among this throng, on our first morning in downtown Lima, the crowd parted to allow the passage of what must be the most striking book display unit ever devised. A wizened man staggered forward, barely able to lift two massive sandwich boards on which was written (in uncertain crayon), 'in this little book are collected

ALL THE SAYINGS OF ALL THE GREAT MEN. UNFORGETTABLE

epigrams! celebrated phrases!' And, swinging on little strings hanging from all around the rim of his hat - like corks on an Australian swagman's hat - were the books themselves! Dozens of copies of a volume so tiny yet plump that it was nearly cubic in shape.

We watched while he made a sale. He cut a book off his hat with a pair of scissors strung to his wrist, and stuffed the money into his hatband. Even Peruvians marvelled.

But we could not stop. Mick wanted to see the Museum of the Inquisition, and we hoped to fit in the Museum of Gold and the Erotic Museum too; as well as the catacombs. 'Don't forget the catacombs!' people kept telling us.

Peru was not the only place to have had an Inquisition, but they seem to have had it more, worse and longer than anyone else.

Our young lady guide to the Hall of the Inquisition spoke English,

Inca-Kola

softly, confidingly. 'The purpose of this procedure,' she said tenderly, as one might advertise lingerie, 'was to make the veins burst.' She knelt beside her waxwork victim, strung with little cheese-wires in a mock-up of the torture, as though herself preparing to administer the final twist. She was pretty, delicate. 'It's my first time,' she told Mick, when he complemented her on her English.

We passed on, into the Inquisitors' Hall. As a mock-up, this seemed rather unimaginative: a bare room with a baroque ceiling, unfurnished except for a polished table. A human skull graced its centre, where a modern hostess might put flowers. But it was not a reconstruction, we discovered. It was the Inquisitors' hall, for the Inquisition only ended in 1820.

We left, passing an entire class of Peruvian schoolgirls on a visit to an exhibition of Peruvian constitutions. The girls' history teacher showed the flair of history teachers everywhere. He had ordered his class to spend the morning copying out the names of all the signatories to all the constitutions, in longhand. He was enjoying a cigarette. 'There have been at least eleven constitutions,' he boasted, as if that were a proof of Peru's affection for constitutional government. He nodded in the direction of his feverishly scribbling students: 'This helps young people feel a sense of identification with their history.'

Outside the hall, there was some sort of show of military strength going on in the square. Armoured cars, a brass band, and soldiers in a variety of uniforms marching up and down. Perhaps Peru was due for its twelfth constitution - but we did not stay to enquire. We were bound for the Gold Museum via the Erotic Museum.

But first the catacombs. Beneath the Church of St Francis lay about a cricket-field's extent of dismembered human skeletons. It seems that Lima buried her dead here for some centuries. When space grew short, they started dismantling the corpses, for ease of storage. Thus, for instance, one encountered a pit of forearms, bones bleached white, neatly stacked in parallel; a pit of skulls, arranged in concentric circles; and a pit of miscellaneous foot bones, like a box of assorted biscuits. We had been warned to watch out for the tribe of scorpions which scuttle among them, but we saw none.

The mood of the day was growing macabre and - sadly - the Erotic Museum failed to cheer, as might have been hoped. The carvings and sculptures - hundreds of them, almost all of couples on each other's backs - were neither art nor pornography. They were not beautiful, for no grace or appreciation of the human form illuminated them; nor were they sexually titillating - the opposite, in fact: like children's comic strips they had been carved with a cartoonist's instinct to mock or poke fun. The overall effect, after an hour's browsing through them, was

Skulls, Feathers and Dollars

deadening. It was like staring into a pond of toads coupling in the spawning season.

Perhaps the Gold Museum would lighten the air? Far from it. The gold itself - tons, seemingly, of weaponry and decoration - might as well have been brass. The main impression was that this was a poor sort of metal, hopelessly soft, upon which the natives had relied, there being no steel. Far from sharing the conquistadors' amazement that the Indians could be so ignorant of gold's value, one began to understand the Indians' amazement that their conquerors were so obsessed with this inferior yellow metal. And they had iron!

One exhibit, though, stayed in the mind, and it was not gold at all. Among a scattering of mummies, leather faces twisted variously into expressions of rage or pain, stood a feathered skull: a bleached, detached human skull to which had been glued thousands of tiny, soft, blue and yellow parrots' feathers. It was covered - upholstered - in a carpet of sky-blue and acid-yellow. Though centuries old, the feathers' colours had kept all their brilliance. Eyeless, two black holes stared out through this gaudy fringe. The old teeth grinned, as through a bank of flowers.

Sometimes (as with African art, for instance) it is hard for a European to know whether the feelings of fear, or beauty, that some mask or carving excites are a European reaction only. Perhaps the object was created for quite another purpose: perhaps it is not really 'art' at all? But to feather this skull, so richly to ornament so grim a symbol of decay - the juxtaposition was timeless in its inspiration, transcending race and culture. It was supposed to be spine-tingling. It was supposed to be grotesque, chilling, beautiful ... like their haunting flute music. And, like the music, it was.

We left the Gold Museum with enough light remaining to sample one of the poorer quarters, a strange pink slum: pink because all the walls had been, well, 'pinkwashed' is the word.

The people looked very poor. There was a smell of urine everywhere and the houses were tiny, segmented by corrugated iron partitions.

Ian explored a bit, even venturing into a funeral parlour. There were literally hundreds of these in Lima. With the hat-shops and banks, they stood out as the only businesses as prosperous and extravagantly fitted out in the poorest of quarters as in the rich. He noticed the prominent display of children's coffins - from schoolboy size down to pathetic baby-coffins in polished wood, adorned with little plastic bunches of flowers, and a place for a photograph of the infant. The cost of one of these, to a poor family, must have been almost unimaginable. Yet poor families would have been this parlour's only customers.

Peering through the iron gates of a state primary school, Mick saw some five hundred children, dressed in a tawdry but discernible uniform

Inca-Kola

and standing in military formation. They were singing the Peruvian national anthem, accompanied by a crackling brass band on a tape recorder. Their headmaster was beating time: 'Somos libres: sedmoslo siempre' ('We are free: let us always be') - 'Ante niegues las luces del sol ...' ('You would deny the light of the sun, before denying that ...')

They had shoes of a sort, and you saw none of the obvious, pathological signs of malnutrition you see in Africa. Just the hard-bitten, pinched, worried little faces of the children of the poor: old before their time, alert to know from which direction the next blow may fall. 'We are free ...' they sang.

The whole quarter was dominated by a vast and imposing modern beer brewery, steam whistling from its aluminium chimneys, and sirens intermittently announcing the labour shifts. It, too, was painted pink. It must have been the source of much local employment - and some local solace ...

At its feet and in its shadow were the run-down remains of a park. It had once been a fine place, a place to see and be seen in. At one end was a convent, pink, like the brewery at the other end. Between them, laid out on classical lines, was what had been the promenading ground of the grandest people in colonial Lima. An avenue of trees - half of them now dead - was interspersed with solid white marble benches and noble stone statues in the Greek style.

You could stand in front of one of these figures - still dignified though her nose was missing, her arms long gone, and political slogans decorated her legs - and look past the statue, past the dying hibiscus bush behind her and past the brewery ... past the sharp little hill beyond, hundreds of tiny tin houses clinging to its mud slopes ... past all that, outward and upward to where - faint in the polluted air - hung a huge cross on a distant mountaintop.

For those for whom the human misery at its feet offered an insufficient prospect, the brewery rumbling among them an inadequate escape, perhaps the cross gave some sort of comfort. Only once did we see an Indian crying, and that was in the cathedral: an old woman sobbing to a gaudy painting of the Virgin Mary.

The poverty, the children, the religious devotion ... it all brought to mind a prayer which Anthony Daniels found pinned by a small icon of the baby Jesus in a corner of that church of San Francisco. He translates it in his book Coups and Cocaine:

'Small Child of my heart, I come before you to ask for yet more favours. Pour your grace on me, give me health of body and soul. Oh my sweet Child! Send down on me a rain of flowers, flowers of your grace, enraptured in their own perfumes. Give me the smile of your lips and the sky of your eyes. Your caresses are worth more to me than all the

Skulls, Feathers and Dollars

joys of the world. With your little hands extended, press me tight in your arms. Take me along the way, and never depart from me, I beg you. Amen.'

Night had fallen when we made our way back across the city. John bought some chocolate from a peasant woman.

Her day's commerce was just ending. Her meagre assortment of wares - chewing gum, cigarettes, some dyed cloths, dog-eared magazines and knitted children's jumpers - were stacked in little piles laid out on newspaper around her, hung on her arms, and pinned to her clothes. She was just a human display rack.

She sold nothing that you could not get from a thousand such hawkers, standing or squatting at the road's edge.

The volume of business she could hope for must have been tiny and the four bars of chocolate, for her, an important sale. But she agreed a price, gave the chocolate and took the money with no hint of triumph or even pleasure: with no trace, in fact, of any kind of emotion. Then she began to pack her goods to go.

She had no barrow and nobody but her little girl to help her; and the little girl was already carrying her baby sister on her back and all the cares of the world across her thin face. Their mother folded and packed every item. The display rack became now a beast of burden. All her stock on board and her two children in tow, she humped and dragged her way back towards wherever home was.

How old was she? It was impossible to say. In this place people's faces turn to leather soon after adolescence; and adolescence comes soon after learning to walk. Boys horse around as boys everywhere do, but little girls seem to have no childhood at all. A twelve-year-old can look soft and virginal. A fifteen-year-old can look worldly-wise, flirtatious and pretty. At thirty-five she is already turning into an old witch, indistinguishable from all the others shuffling their way down the road - as our chocolate seller now was.

'But she's still moving,' said Mick. 'It's the ones who have stopped moving who are finished, in Lima.'

Chapter Three

To The Mountains

Everyone had told us that bus stations are the worst places for thieves. But we forgot. Bright lights, bustle and noise seem so unthreatening. Besides, we were excited for we were going to Huaraz.

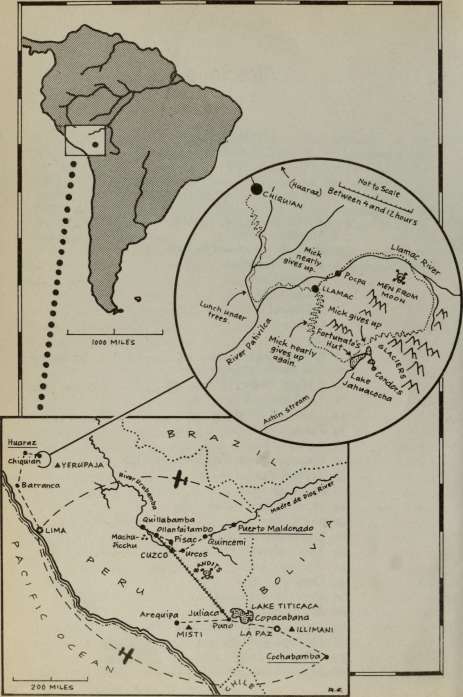

The town of Huaraz lies north of Lima and high in the mountains, between the spectacular ranges of the Cordillera Blanca and the Cordillera Huaywash. That was where we wanted to go - walking in the Huaywash mountains. So, first, we had to reach Huaraz.

Peru consists of a long Pacific coastline and, behind it, an equally long narrow desert strip. Behind that rise the Andes, which run the whole length of the country. And on the other side of the mountains lie the jungles of the Amazon basin. Wherever you start, if you start from the sea and head inland, your cross-section of Peru will be the same: desert, mountains, jungle. But there are relatively few points on Peru's long coastline where it is possible to find an easy passage up into the mountains.

Only one spectacular railway makes the ascent direct from Lima itself (and it is one of the railway wonders of the world). But once you have climbed up behind the city, winding your way all day to the high Andes, it becomes a slow and complicated matter to journey further. Easier by far to follow the coast up or down until you are within striking distance of whichever part of the Andes you want, then head inland and up.

So almost all lines of communication from Lima start by going north (up the Pacific coast) or south (down it): and buses to Huaraz were no exception, though the town lies well inland from the coast and high above the sea. That was the way our route started: due north by the Pacific, a route followed by the bus company Empresa Rodriguez.

Long-distance transport in Peru almost always travels by night, leaving after dusk. It was at nightfall, then, that we reached the premises of the Empresa Rodriguez.

Each company has its own offices, 'terminus' (usually a cramped, walled

To The Mountains

yard) and waiting room. Tickets purchased, we sat among scores of peasants in a scruffy room. It felt safe after the unlit streets of the rundown quarter where buses bound for northern destinations start.

Our heap of rucksacks, hold-alls and plastic bags looked no richer pickings than the flour-sacks and cardboard boxes which the Indian families were guarding; and it seemed natural for three of us to leave the fourth keeping watch while they shovelled down gristly meat and fried eggs in a verminous eating-house nearby.

And when hunger overcame the fourth - well, why not get a respectable-looking grandmother on the next bench to keep an eye on our belongings? She agreed; but the others were doubtful and Mick and John gobbled their meal, returning fast. Everything was still there, and a little later the woman left to catch her own bus. That left two of them to keep watch.

Mick hurried back to where we were still eating to warn us that it looked as though our bus, too, would soon be leaving. He left John with the bags, chatting with another woman who spoke some English. After a moment, and with Mick gone, she asked John to help her move some boxes. How - as he said to us later - could he have refused?

No doubt that was when the bag with Mick's passport in it disappeared.

Chaos reigned. Mick stared wildly about him while the rest of us searched mindlessly and repeatedly through the remaining baggage and beseeched the other passengers (in broken Spanish) to help. They seemed as bewildered as we were.

At that point the departure of our bus was announced.

It was one of these frozen moments when whoever fills the void with a suggestion - any suggestion - is likely to be followed. If anyone had said, 'Back to the hotel: it would be crazy to go on without a passport. Foreigners have to carry them and the British Consulate must make a start on preparing a replacement. We can see a little more of Lima while Mick arranges things ... then that is certainly what we would have done. As it was, somebody said, 'Fuck the passport; let's go!'

And that is what we did.

As we pulled away, Mick realized that his bus ticket had been stolen too. Curiously, the conductor accepted this without question - just as, previously, the grandmother had accepted our baggage and we had accepted her honesty. Thieving and honesty, suspicion and trust... they live side by side in Peru. In Europe everything mingles and dilutes into a higher level of mistrust - and a lower level of thieving.

'Bloody Peruvians,' said John. 'Of course tourists like us are their latural prey.' He said it as though the whole waiting-room had been in

conspiracy against us, and Peruvians never robbed each other. He voiced the mood of all of us.

Inca-Kola

Our bus was about Ian's age. A couple of decades (perhaps) of service had left it battered, tired, but still pretty much in one piece, mechanically. The seats smelled of mouldy cloth, vomit, biscuits, mango and old leather. We settled back to peer through grimy windows as the elderly machine lurched and roared through the endless miles of rickety telegraph poles, breeze-block cabins, dead dogs and iron-roofed shacks that stretch north of the city.

Not long after we had started, a middle-aged peasant woman discovered that her own small bag had gone too. She had stowed it in the rack above her seat.

Her grief was enormous. It seemed the more poignant for the soft, insistent voice in which she appealed directly to each row of passengers, one after the other. 'Sister,' she would say - or 'Brothers,' - 'my name is Isadora Fernandez. I beg you - there is nothing of value in that bag -no silver. Just old clothes. My own belongings ...'

People looked embarrassed and avoided her eyes. But she continued, softly, insistently. A bus careered past us, overtaking. Caught momentarily in our headlights, the motto emblazoned across its tailboard announced, 'my nobility pardons your ignorance'. For a moment her voice was drowned in the roar of its exhaust, but she carried on, pleading.

Eventually the conductor asked her to sit down. She did so without resisting. At this point she simply gave up - completely - and began to cry. Nothing more was said. She just sat there sobbing quietly, it seemed for hours.

All was black outside. We were in fact travelling north along the desert coast where the road was straight and fast, and towns were few. To our right, a few miles inland, loomed the great dry fingers of the Andes. Wave upon wave of desolate foothills, each higher than the last, reached back and up towards a land which was unbelievably high - another world, a world of ice and wind and flowers.

But the desert at its feet gave no trace of that other world towering on our right hand. Moonlight, white on the bony ridge of foothills, showed nothing of what lay behind. Black streams, littered and stagnant-looking, seeped through the sand and stones, betraying no memory of the glaciers from which they had descended.

To our left, the caps of great Pacific rollers far out to sea flashed silver in the same moonlight. How far to New Zealand? Seven thousand miles?

This was the edge, a thin line between two great emptinesses: the ocean and the mountains. Looking out towards the ocean rollers on one hand, the dunes and foothills on the other - things magnificent in themselves yet unnamed and uncelebrated, only the fringes of what lay

To The Mountains

out of sight - you had a sense of something no English landscape can inspire. It is the feeling that what lies within vision is only just the beginning of what waits beyond.

Before we started the climb, the bus paused ('For your comfort and refreshment,' as the driver announced, waking us up). What time was it? We had lost all sense of time. Almost everyone had been asleep. We tottered out: peasants (some of the Indian women in their own dress: bright skirts in scarlets, oranges and crimsons, worn over many layers of petticoat; most of the Indian men in shabby western clothes), whiter Peruvians, and us. We were the only foreigners on board.

All stumbled, blinking into the harsh glare of the security lamp that lit the yard. It was our first chance to size each other up.

Few Peruvians own cars. People of all walks of life (bar the richest) must use buses; and for most they are the only means of reaching distant places.

Nor do the poorer people travel often. Long bus journeys have an aura of great occasion for passengers: hampers are packed, cardboard boxes and old flour-sacks are laced intricately up in what looks like weeks of preparation. The fares - ludicrously small to us, a few dollars for hundreds of miles - may have been carefully saved over months.

And, where travellers in Europe find themselves among people for whom the journey is routine, in Peru the coaches streaming into and out of Lima are filled with individuals for each of whom the occasion is exciting and strange. We noticed as we wandered bewilderedly from our bus that many of our Indian fellow travellers were equally baffled, with just as little idea where we were or what we were supposed to do.

How did they react to us? With wary, sidelong interest.

Strangers seldom stared and almost never confronted us with direct enquiry or even eye-contact. It almost seemed that the presence of foreigners had not even been noticed. Then a look, a glance hastily averted when returned, discussion overheard (unintelligible in itself, but how easy it is to tell when someone is talking about you!) - and curiosity was betrayed.

There was a warehouse-like canteen nearby, where it seemed that in exchange for a little square of scissor-cut notepaper bought from an old lady at the door, you would be served with thin soup, bread and tea. Many made their way in.

Outside, on the side of the bus facing the lighted canteen, the men were carefully pissing on its wheels. On the dark side of the bus, shadows of Indian women, squatting to face the deserted road, moved dimly.

The air was hot and still. Flying insects buzzed around the glaring light high above.

From another building, some hundreds of yards away, came the sound

Inca-Kola

of Latin music. On closer inspection this appeared to be the last stages of a celebration dance night. A score of couples shuffled to a slow dance on a scratched recording played through a distorting amplifier. They clung to each other in that alloy of passion and fatigue characteristic of the last half-hour of late-night dance parties anywhere in the world. One needed no watch to reckon that the time was about half past three.

A convoy of trucks thundered past, blaring horns and wrecking the calculations of the squatting women. They scattered in dismay, and were further disturbed by a flurry of activity from our own bus; for it was time to go. The driver revved the engine and flashed the lights. Skirts were hitched up in panic. Some of the passengers started screaming to friends and family still outside.

It was now that Ian made what seemed at first a most unlucky move.

It started when our bus drove off without one of the passengers.

They had nicknamed him El Gordo (The Fat One). He was a grossly overweight, middle-aged travelling salesman (we never quite worked out in what) whose shabby suit was literally bursting at its seams, and who perspired continuously. He was probably on his third helping of soup as the bus pulled away. 'Falta El Gordo' (El Gordo is missing), Ian shouted. Other passengers took up the cry. l Falta El Gordo,' yelled the whole bus.

We shuddered to a halt. Far back, in the dust, El Gordo could be seen, waddling desperately behind us, calling for us to wait. He caught up - panting - and heaved himself up the steps, soaked with sweat, to general laughter.

What happened next seemed so unfair to Ian. El Gordo was standing at the front of the bus, Ian sitting (with us) in the back seats. But El Gordo's own seat, which should have been waiting for him, seemed to have disappeared. This was not surprising. Ever since our departure from Lima, no one had wanted his huge bulk next to them because he overflowed hopelessly into surrounding seats.

But he had eventually established a place next to an Indian mother. Mothers can be ruthless. She was the dog who hadn't barked when he failed to board, leaving Ian to announce that he was missing. She it was who had made quick use of his absence and conjured children out of nowhere to fill his seat.

El Gordo lurched, still perspiring, down the gangway, eyeing every slight gap between passengers. But as fast as he spotted gaps, passengers moved to close them. 'No! No! El Gordo no!' they chanted. The women shrieked with laughter as The Fat One ran the gauntlet of their inhospitality, row by row. Moving down from the front of the bus, still searching, he neared the back.

A look of alarm grew on Ian's face as the inevitable became clear. He was at the very back, the terminus of El Gordo's hopeless search. And

To The Mountains

there was a tiny space just next to him. As relief spread across El Gordo's plump features, there was horror in Ian's eyes.

Into the gap crashed El Gordo, shirt dripping. Did the offending hulk realize that it was his saviour whom he now almost crushed? Probably not. Ian groaned. The whole bus grinned.

We lurched forward again, on into the darkness. One by one, each of us fell asleep. El Gordo snored peacefully; the woman who had evicted him was comfortable now, her children around her. Senora Fernandez had stopped crying and was calm. Mick and John dozed. Even Ian drifted off, as one pinned helplessly underground in a mining disaster might drift from consciousness.

That we started to climb, and climbed continuously until dawn, we knew more as you know it on an aeroplane than on a bus. We could see almost nothing outside; but it was easy to tell that the road was winding up the side of the Andes. Through a fitful sleep we were conscious of the whole dead weight of the bus heaving regularly, left to right, then back again. The springs creaked and the luggage piled on the roof above shifted heavily. The moon swung wildly across the windows as we hairpinned upwards - not for ten minutes as in Scotland, or twenty as in Switzerland: but for the whole of the rest of the night ... left, right, left...

The slope of the bus floor, steeply uphill, stayed constant while the stars outside spun crazily in the sky. From time to time a child cried, but mostly there was silence, and darkness without. Little clusters of lights down on the coast, now so far below us, were sometimes visible, and the spines of mountain ridges showed white and skeletal in the moonlight, like the bones of hands reaching down towards them. We seemed to be climbing through thin air.

Once the bus stopped, rather before dawn. When we got to our feet to stretch our legs, we found ourselves breathing hard in the rarefied atmosphere.

It was getting very cold. The bus had no heating at all. All around us the peasants produced blankets, ponchos and shawls - from nowhere, it seemed, as conjurors produce silk scarves - and disappeared beneath them. The windows, already misted over, froze on the inside.

John shivered and felt sick. Mick's feet were so cold that he put all his socks on, planted his legs in a plastic bag, then placed the whole bundle into a travelling bag. This completely immobilized him.

It was then that we noticed Ian. No longer recoiling from El Gordo he had now snuggled right up close, almost enveloped by one fatty flank. El Gordo himself, a warm, slumbering mound, heaved rhythmically with gentle snores. Alone among us, Ian was warm, his face a picture of peaceful repose. Virtue had had its reward.

*

Inca-Kola

Dawn was a steely-grey affair. It came when we finally stopped climbing and emerged upon a bleak scene: a treeless, windswept plateau strewn with black rocks and frozen ponds.

There was a science-fiction look about the place. Clusters of snowy peaks needled high into streaks of ice-cloud. There was absolutely no colour.

It was a dispiriting landscape. With the dawn, John woke up, looked out and started to retch. Mick gave him his plastic bag, and John clenched his teeth and stared grimly around at the harsh world about us.

The sun edged above the rocks.

Quite suddenly, a distant mountaintop caught its rays and burst into flame. A yellow-orange streak fell across the monochrome scene. In the thin and freezing air every line, every colour was sharp. All was jagged. There were no curves, no fading, no blurring. It looked like a different universe, in which our bus moved like an alien capsule from a softer, fleshier world. You felt that if you left the bus and walked in this new world you might cut your feet even on a blade of grass. It was beautiful.

A peasant woman near me murmured l Cristalina' (Crystalline). It was said almost reverently and I looked across at her. She was old and withered: like a potato baked too long in its jacket, leathery-tough against a harsh world. You would have thought that she had long lost any capacity for tenderness. Yet she was staring out now at a scene with which she may have been familiar since birth - still lost in wonder.

There is an idea that physical hardship dulls the sensibilities or somehow thickens the skin; that the poor are hard-bitten emotionally, too; that they lose the capacity to see and love beauty.

But perhaps that is just an illusion with which the rich have always comforted themselves. I remembered a Jamaican woman to whom my mother often gave a lift as she tramped her way every day through miles of blistering heat from her cleaning job in Kingston to her shack up in the hills. She had had a hard life, her man had left her and she was trying to raise seven children.

She became pregnant - in her fifties - when it was the last thing she wanted. The child was stillborn. A blessing, we all thought.

But she cried for days, almost without ceasing. You would see her toiling up the hill, her eyes red with weeping. The sun had burned her skin but had dried nothing that was within.

Could it be that what we are never changes, but is only overlaid, scar on scar, by what comes after? My friend Colin Welch once recalled that at his mother's death he had an impression of the ruined hulk of an old ship sinking beneath the water, dragging down with it a little girl, screaming from the vessel's heart, trapped.

To The Mountains

The old Indian woman began to sing, quietly. Passengers started to talk, exclaiming, pointing. You would expect a sense of wonder at the natural world from foreigners to whom this was new and strange, but South American Indians - even the humblest or most downtrodden - seem to love their environment. Reserved about expressing other feelings, their love of beauty goes quite unhidden.

Even John awoke and cheered up. 'Classic torrent-duck country,' he whispered weakly, peering out at the stream we were following.

And now we began to descend again. Not steeply or far, but winding down beside a stream which flowed along a broadening, deepening valley. We bowled down the road, warming in the first rays of the sun, passengers chatting excitedly, babies clamped to breasts. And outside, too, the bleakness was giving way to small fields, green crops, donkeys laden with produce, children waving, and from many hearths the thin plumes of breakfast fires.

Brush-stroke by brush-stroke the morning was being painted in. The grey-and-black outlines of the night ride receded. It began to seem as though everything had been a strange dream.

With much honking and revving of engines, we arrived in Huaraz.

Chapter Four

A Small Riot

It was very early in the morning and still frosty. Behind the town mountains rose up so vast and high and white that Huaraz seemed to nestle at the foot of things - and you forgot its own great elevation above the sea.

Until, that is, you tried to do anything. Running, lifting, or walking uphill quickly left you breathless; and a persistent, thin headache reminded you that at an altitude of 10,000 feet it was best to take things slowly at first: to find the centre of town, perhaps, and look for somewhere to stay, and rest. John still felt pretty ill, and after the bus ride a room with beds was the first thing on all our minds. None of us was hungry.

Morale improved as we shook off the travel-shock and began to drink in the morning air and to feel part of the place where we were.

Huaraz was just waking up, emerging from the long blue shadows of the mountains into thin yellow sunshine.

With sacks of animal fodder and green foliage on their backs, boxes of eggs, chickens and bicycle spares in tow, people and donkeys moved through the street towards the market. We followed the tide.

Huaraz is a modest town which gives little hint of its horrific history. In 1941 much of the town was swept away when a lake in the mountains above broke in an earth tremor and 6,000 people died. Then, in 1970, came a terrible earthquake which all but wiped out the town, killing half of its inhabitants. This earthquake went wider than Huaraz. In total it killed some 80,000 people, and days passed before rescue workers could even reach the region. It was one of the worst natural disasters in the history of mankind. Curiously, it seems to be largely forgotten, today. For the second time this century, the people of Huaraz set to rebuilding their town.

Its buildings are low - mud-brick and breeze-block - and its architecture undistinguished. There is nothing spectacular about the place: just a breathtaking backdrop and a feeling of quiet local sufficiency. It

A Small Riot

is the hub of a sheltered valley, comfortably farmed. To the poorer Indians, riding down from the mountain slopes, it must have seemed a land of milk and honey.

At an altitude where the air is thin, sunlight is hotter and shadow colder. We stood on the sunny side of the road by a little tin shack. Its kerosene pressure cooker roared while they made us tea: hot, weak and sweet, with no milk. We watched the shadows of the rooftops traced out in frost on the dust. As the shadows moved, so the frost melted -maybe ten seconds behind. It gave each retreating shadow a thin edge of frost exposed to the sunlight: a temporary etching, brilliant white, following the shadow backwards.

Stalls were opening and the town was coming to life. Longhaired auburn pigs, polka-dotted pigs and pigs with tortoiseshell patches rootled around among stalls which sold underpants, herbal medicines, little tubs of aniline dye in acid colours, soap, condensed milk - and hats. Every second stall seemed to be a hat stand.

Everyone wore a hat. The local fashion seemed to be for a sort of white straw hat of the type that elderly gentlemen in the British Legion wear for bowls matches. Ian tried a couple on for himself. The young woman selling them screamed with laughter.

A very, very old man shuffled past, bent double beneath a bundle of branches three times his size. A woman in high heels with matching suit and handbag promenaded by at a quickstep, as if tugged by some outside force. At second glance, she was: a pet racoon strained at the end of a scarlet leash. It was neatly brushed and wore an expression of utter determination. The pair of them stormed onward, slaloming between pot-holes.

John was suffering badly from diarrhoea. Twice he had dived behind the nearest hut, in the nick of time. Now he felt a sudden hunger.

Seeing this as a hopeful sign (he had not eaten since Lima) we bought him a hardboiled egg, still warm from the market and wrapped it in our second purchase: a pair of underpants to replace those which diarrhoea had taken beyond recall. The new ones were purple with a green portrait of Charlie Chaplin on the front. This design seemed the most popular with the Indians.

Ian finally chose a dashing broad-brimmed straw hat, and found a card for his girlfriend. John, despite his illness, began what was to become an epic search for a jumper suitable for his wife. It had to have llamas on it, and had to be in alpaca wool, coloured in pastel blues and pinks, and of the right size for a girl who was six inches taller than most Peruvian men. Huaraz was the first place, but not the last, to fail to produce jumpers possessing all these qualities at once. Yet somehow John never lost heart.

Mick's Spanish turned out to be near-perfect. Equally important, he

Inca-Kola

had an almost saintly willingness to translate everything for everyone else. It worked well for him today, for he found what we never found again, a street telephone-kiosk from which you could make international telephone calls, using special tokens which you had to toss in at an alarming rate. Mick rang his wife.

We caught his last words to her before he ran out of tokens: '... and have you remembered to water the tomatoes?' Then he was cut off. The tomatoes had been worrying him since he had last phoned home from Bogota.

Mick stared blankly for an instant, returning mentally from the old familiar world to this bewildering place of rootling piglets, soldiers in toytown uniforms and sad-eyed old peasant women.

We regathered. We were tired. The bus ride and the altitude were catching up with us. It was getting hotter; and our bags were heavy.

A mestizo in an oily shirt filling kerosene drums had heard of the hotel our guidebook recommended. A lighted cigarette hanging from his lip, he wiped the kerosene from the top of the drum, pointed the way, and warned that it was a steep walk.

It didn't look steep, and we could see the building we were aiming for. But John barely made it, and the rest of us were glad to have him as the excuse for pausing breathlessly along the way. Morale improved when we reached the hotel. It was clean, pleasant and unbelievably cheap. The six-bedded room that Mick negotiated for us had a magnificent view straight over the town and up to the ice-peaks beyond. From one you could see a thin stream of snow blowing from the top in an apparently motionless line - sharp and straight as an architect's drawing - shining in the midday sun. John collapsed on to a hard bed.

It was a day before he could walk again. John was an uncomplaining type, and quite tough. If he said he was ill, then it was bad.

It was harder to tell with Mick. His health was important to us, for not only was he an expert interpreter, but he seemed to have an ability to strike up with people we met. He was often our bridge with Peruvians. Complaining already of diarrhoea and nausea, he showed a lively interest in the symptoms. We had yet to learn that it was when he stopped talking about illness that his companions needed to start worrying.

Ian was our ambassador towards children. It did not seem to matter that he spoke no Spanish: young people were immediately drawn towards him, and he to them. Already, in the market, we had left him a few minutes and returned to find him playing street football with a gang of youths with whom he was quite unable to converse. After that he had been mobbed by a little bunch of adoring boys and girls, who had started to teach him Spanish. Something about his open face and fair hair attracted and fascinated the Indian people, and infants would

A Small Riot

babble excitedly to him, baffled but not deterred by his failure to understand or respond to a word they said.

But the football had left Ian with a sick headache which grew as the day wore on. To a greater or lesser degree, we were all affected by the altitude, and glad of the security lent by our room. Burning already from our first day in the Andean sun, we lay around, feebly discussing what we might do once John recovered. 'Iff said Mick.

We wanted to begin at a village called Chiquian. From there we could take a ten-day walk in the Cordillera Huaywash, an isolated and (it was said) magnificent range. We had the maps and equipment needed for a hiking expedition right through the range.

But how to get to Chiquian? It looked about a day's truck journey away, back south in the direction of Lima, but further inland.

Mick had found out that there were occasional local buses, but advice about them was conflicting. The most confident opinion we had received came from a kerosene stove repairer ('Gas Fitero' was the description above his shop) who said buses were uncertain, but trucks left every morning from outside his shop. If we turned up in time, he said, we could negotiate a ride to Chiquian. Other people did.

We resolved to try.

Then John was sick again. Mick became convinced that this was pulmonary oedema, an illness (he had read) afflicting those unused to altitude, leading often to death: an illness of which we were to hear much more from him. The rest of us thought it more likely that it was something John had eaten. Mick reacted to this frivolously irresponsible diagnosis with a reproachful stare.

In any case, we all agreed that it was best to wait for at least another day, and hope that John recovered sufficiently.

By the following day, he was well enough to join us in observing a small riot.

We thought at the time that this was rather sensational. Were we, perhaps, witnesses to the triggering of another South American revolution? Only with time did we come to understand the matter-of-fact disregard with which onlookers treated this, and other, public demonstrations.

The Peruvian economy was falling apart. A relatively democratic government, of centre-left ideology, had been doing its best for some years to please most of the people for most of the time. It had spent more than it could find and inflated the currency to do so. It had defaulted on some of its international debts and lost the ability to raise new ones. It had promised more reforms than it could deliver and tried to control and nationalize more of Peruvian life than it could competently handle.

Inca-Kola

Gravest of all, it had pretended that the country's chronic Maoist terrorist problem would simply go away now that a leftist government was in power. In fact, the terrorists had sneered at compromise, redoubled their activities, and left a bankrupt administration relying on military suppression which they could not afford and which was not working.

Inflation was halving the value of money every few months. Private commerce was desperate; saving and investment had become a nightmare. State employees were hopelessly underpaid and the state unable to raise their pay as fast as inflation undermined it. Many were now little short of frantic.

Schoolteachers were a case in point, and the cause of the riot we were now to see. It seemed that teachers were on strike for a doubling of their salaries; a reasonable-sounding demand when you realized that it was a year since their last raise, and inflation had halved its value in a far shorter time. But the strike had dragged on for weeks and nobody seemed to care. Children stayed at home or played in the streets. So the strikers had gathered with placards in the main square for a demonstration. We watched.

It was all pretty low-key, at first. Teachers marched around waving pieces of cardboard with their demands written on them. The rest of the populace stared with mild interest at the scene.

Then the local police, backed by the army, piled in. They arrived in armoured cars, and advanced on the demonstrators with riot shields.

At this the strikers felt obliged to riot, which they did by shouting and throwing a few stones rather half-heartedly at the police. The police responded by dragging a few of them off, and drenching the others with water-cannon. This seemed to satisfy honour on both sides, and uninvolved spectators - the citizens of Huaraz, who had watched politely until now - moved off to do something else. The riot was over.

Something about the reaction of the spectators would perplex any European: you could not tell whose side they were on. Like commuters in an English railway carriage, nobody wanted to draw attention to themselves by shouting - or even talking. Nobody joined in. A few -just a few - of those watching looked utterly absorbed. Others were just amused. Yet on all sides the approach was - again - like that of railway passengers you catch peeping over the top of sheltering newspapers: not involved, not wishing even to register an interest, but curious. Such reserve does not fit the popular image of South Americans; but it is very marked among Peruvians.

That night, however, we did get some sense of popular protest.

It was about ten o'clock. John had decided to try eating again, and after a reasonable meal we came out onto the square by the church.

A Small Riot

Something seemed to be going on, so we joined a large crowd to find out what it was they had gathered around.

It turned out to be impromptu street theatre, not the self-conscious Arts Council-sponsored sort of thing one sees in England: just two men - one more Indian, the other more Spanish in appearance - with a handful of shabby props and a non-stop flow of hilarious mimicry and banter. The crowd roared its approval.

Even Mick could not get all the nuances, but he translated as best he could. The men were lampooning the government, the police and the armed forces.

In one sketch the more Indian of the pair joined the army. He was given a uniform. As he put it on his whole demeanour - and finally his whole personality - changed. He began to high-step around, haranguing members of the audience.

Then he was given orders to kill strikers and demonstrators; this he mimed in such a flashy display of bravado that - as 'soldier' - he almost gained the audience's regard. But this spell was broken when his partner brought him news of trouble at home: death and hardship in his own village. It stopped him in his tracks. He looked down, ashamed, at his uniform, and began to take it off, piece by piece, changing back into his ragged peasant clothes, and weeping. For the second time, his whole character changed.

It is impossible to convey how funnily, and how movingly, this was done. Looking back, it is hard to explain how such a comic-strip performance could spellbind a hard-bitten street audience. Undeniably the performers had talent: but they had the sympathy, and the whole attention, of three or four hundred people. This was what made the performance work.

The peasant-turned-soldier-turned-defector now joined the revolutionaries. Here, you could sense that the act began to lose a few of its audience, and to discomfit others: but for the bulk of them the effect was to move them, emotionally and politically, just a little further than they had intended down a road they were already disposed to travel.

It was the cleverest kind of propaganda because it used the emotions that ideologues (particularly on the left) so often fail to engage: humour and sympathy. Just when the groundlings and the children in the audience were getting impatient with the serious message, the actors deftly switched back into comedy.

They did so after this sketch, passing round the hat with the announcement that 10,000 intis (not much) would secure one more act. 'Fifty intis each' they said - then, realizing that there were four foreigners in their audience, rounded on the most embarrassed, John. 'That equals one hundred dollars, Gringo!' they said to him. The audience roared with laughter, but it was good-humoured laughter.

*5

Inca-Kola

The hat was quickly full of money. If there were more than the 10,000 intis demanded, the Spanish-looking actor said, they would return the balance. They started to count the money out, aloud.

It takes a skilful comic (and a receptive audience) to create a hilarious stage routine out of the counting, on stage, of 10,000 intis in notes of small denominations. But an uninterrupted flow of wisecracks kept the audience in the actors' hands. Then, at precisely the point when it became clear to the audience that there was a great deal more than 10,000 intis in the hat, but just before that figure was actually reached, our two entertainers announced that the target had been met - just -and stuffed all the rest of the money into their pockets. There was a great shout of laughter from the crowd.

A slight enough joke. To see it engage a crowd of hundreds on a piece of ragged turf in a noisy square, with no seats, no special effects, no sound amplification, and no illumination but the street lamp, gave a sense of what Elizabethan theatre might have been like. It made it easier to understand why so many of Shakespeare's comic scenes - hopelessly unfunny when studied for examinations and scarcely better when performed by the Royal Shakespeare Company - were put there.

'Revolutionaries' were mentioned often. The word 'terrorist' never was. Nor was the Shining Path. But a tension in the humour and in the audience's reaction to it pointed to what nobody needed to say: that the Shining Path were the revolutionary challengers.

We did not at that time know much about the Sendero Luminoso -Luminous Pathway or (as the western press style them) Shining Path. They are perhaps one of the most bizarre - and macabre - terrorist groups in history. Attributing their ideological birth to a half-caste with a falsetto voice (long dead) and led by a mysterious university don called Dr Abimael Guzman who is widely believed to have been killed but is still rumoured by some to be alive, the Sendero now operate among the Indian peasants and in the poorest parts of Peru.

One province was almost entirely out of the government's control, and the revolutionaries were active in many other regions and cities. Their areas of operation were, we were told in tones that were half-excited and half-alarmed, spreading. Their ideology was said to be a gothic amalgam of unreconstructed Maoism and ancient Inca belief.

Their methods were utterly ruthless. Animals were driven into market stuffed with explosives, and detonated. A little girl had been used in the same way - to walk into a crowded hotel lobby in Lima.

Guzman's doctoral thesis was on the eighteenth century German philosopher Immanuel Kant, a man so ordered in his habits that it was said you could time your watch by his leaving his house each morning. Kant might be surprised to see his student Abimael's donkeys exploding

A Small Riot

all over Peru. Villages or communities were 'turned' to the Sendero cause by intimidation (their critics claimed), whereupon government troops employed the same approach to 'punish' the community and regain its loyalty.

The revolutionaries differed from many other groups in that they seemed to have little interest in their international standing. They had not aimed to attract attention outside Peru. And, even within the country, they hardly seemed to be spreading the ideological word, publicizing their aims or trying to win support or sympathy by argument. Their purpose seemed to be simple: to destroy, to spread fear.

The very mention of their name in Peru sent a nervous chill down the spine: whether of excitement or dread depended upon the audience, and was often very difficult to tell.

So it was, we noticed, with the crowd we now found ourselves among.

And something else Mick noticed. The importance of uniforms. It strikes you again and again in South America. In this street theatre it had really been the central theme. The soldier changed from human into monster when he put on his uniform. But he also changed from fearful to fearsome, from shabby to macho.

Mick contrasted the type of stiff-necked official we had already encountered - and they do not come more stiff-necked or official than in the Latin countries - with the warm and easy going natures that are otherwise a pleasant general rule. Yet these are usually the same individuals: two sides of the same personality.

How can people who are normally so relaxed be so different behind a desk or a sub-machine gun? The change follows upon the assuming of an official position, and the outward sign is a uniform.

Perhaps some races find the tension between the human and the official irreconcilable? The wearing of a uniform may be a sign that the attempt has been abandoned, and the two halves of the personality allowed to split and go separate ways.

We English would pride ourselves, perhaps, on a steadier personality. But maybe that just means we need no uniform to be officious. We are perfectly capable of dressing casual and acting formal at the same time: we slip naturally into behaving like traffic wardens, at home or at work. But never with the manic inhumanity of a South American official! The on-duty and off-duty sides to an English nature - if they are at war at all - have usually met half way in some sort of truce.

It may mean that we will produce neither the world's best traffic wardens nor the world's best lovers, but at least we have traffic wardens who are not impossible to love, and lovers who are not impossible to control.

We walked home, much affected by the street theatre and the riot we had seen that day.

Inca-Kola

We awoke early and were packed and waiting at the kerbside spot to which we had been directed, far earlier than we needed to be.

The truck was called Divine Light. It had rampant tigers painted on to the rear mud-flaps. Across the front, on the wooden panel above the cab's windscreen, where every truck bore its name, was written Luz Divina, and, beside this, a picture in original oils of a condor, couchant, with her chicks.

Divine Light waited for an hour or more outside the Gas Fitero's shop while the driver sorted out the cargo. He was a little man, with more Spanish than Indian blood, called Lazarus.

Truck drivers are a special breed in Peru, carrying status in society. Often they will have a much younger assistant who himself rarely drives, generally acting as overseer of cargo and passengers and collector of fares. Most drivers seemed to be small, cynically good-humoured men. Lazarus was both. Most are middle-aged and stoical. Lazarus was both. Middle age, perhaps, was the time when your apprentice years were served and you moved into the driver's seat. Stoicism was the quality needed to face the daily peril sent by your job. The daily peril was no doubt the reason few got much beyond middle age!

He asked us to keep watch over his cab while he made a few calls on foot in the town. John, who was still weak, rested in the shade. Ian sweated it out in the sun because he had promised his girlfriend a suntan. Sporting his new hat and leaning against a battered classic car - a 1958 Ford Zephyr - he looked the part. He always did. It was just that it was never quite clear what the film was. Before long he was scoring in a street football game with a gang of youths.

Mick, still worrying about his tomatoes, sloped off in search of oranges and biscuits for the journey.

From some shack around the corner, crackling over a street vendor's loudspeaker, came the sound of Andean, Indian music. The emotional power of this music is hard to explain: it has to be heard. One can only describe the most common instruments: a sort of lute-like guitar more jangling in sound than our guitars, a wooden flute and an instrument which looks like the stacked pipes of a church organ constructed in miniature out of bamboo sticks, and sounds like someone blowing over the top of a Coca Cola bottle.

The important difference between their flute and ours is that theirs is played with fluid, sliding notes, like a man whistling. When two or more of these flutes are played together there will always be a slight dissonance between them, as occurs when people whistle in harmony, because each is wavering fractionally above and below the desired note, hunting the mark. This causes a curdling discord at the very high frequencies which a flute (or whistle) emits. The result is a spine-chilling edge to the sound.

A Small Riot

It is extraordinarily poignant: enormous emotional power yet with a strange cold streak.

After some time, Lazarus returned to say it would be an hour or more before Divine Light was ready to depart. So we wandered off to see if this music could be bought, on cassette. It could. We returned later, after some more weak tea in tin mugs, with our musical souvenirs.

But while we were away, Lazarus, who had been supervising the loading of the truck, had been robbed. A quick-witted thief had got into his cab and removed his tape-player while he was behind the vehicle. Lazarus took it philosophically. We were quietly relieved it had not happened while any of us was in charge.

It was time to claim space in the back of the truck, on top of the cargo among the other passengers now starting to arrive. Ian wore his straw hat tied under the chin with a woven ribbon a little girl had given him. Mick was modelling a bright orange deerstalker-type cap with 'toyota' printed across the top, bought from another stall. John, stretched out in a little pit immediately behind the cab, peered wanly up at the magnificent peaks that soared above the mud walls and tin roofs and dusty streets of the little town.

He said: 'When you look at how beautiful the background of mountains is, and compare it with how shabby and filthy this place of Huaraz is, the two don't seem to go together.'

Brought up, like all of us, on picture books of Alpine peaks and neat Swiss chalets, flower-boxes spilling over with geraniums, and clean looking lads and lasses dancing on green meadows, it was easy to forget that the power of those mountains was beyond 'clean' or 'dirty'. Later we would see the corpses of mountaineers being brought down from the slopes that now glistened so hygienically in the sun.

Three blasts of the horn and off we went, rocking and rattling down the main street leading out of Huaraz. Narrowly we avoided a large uncovered sewage shaft, gaping in the middle of the road. A concerned citizen had placed a huge rock beside it as a warning.

As the truck lurched, John groaned. 'To me this is hell,' he said.

I stood at the front with the wind in my face. To me it was paradise.

Chapter Five

Divine Light

In Peru, people with any position in society do not travel in the backs of trucks. In the unlikely event that they would need to visit a place served only by trucks, money (or influence) would secure them a place in the cab, with the driver.

Trucks, in short, bring you into contact with the humblest Peruvians.

Divine Light was a twenty-ton, two-axled truck. She was in moderate condition. Outside Lima, and wherever really rough road conditions were common, vehicles might be elderly and battered, but mechanical condition was usually basically sound. Whatever the look of a truck or bus, you could be fairly sure that the things that mattered - engine, transmission, suspension - were there. Rather less attention was paid to brakes, and none at all to tyres.

Our truck's chassis and body were built in Lima, the engine and gearbox imported from the USA. She ran twice weekly from Chiquian, bringing in produce to the market in Huaraz. The return journey (carrying us) offered less cargo: a consignment of wooden poles, four 44-gallon drums of diesel, one of petrol and one of kerosene, some spare parts for Chiquian's diesel-powered electricity generator and ten crates of Coca-Cola.

But we had our full complement of passengers. The team was dominated by four fine-looking Indian men, in traditional ponchos and hats, blind drunk. Alongside them, but keeping her distance in an elaborate frock and hat and a good deal of dignity, was a middle-aged lady and her infant granddaughter - all dressed up for the great expedition.

Then there was a teenage boy, thin as a rake, who helped the driver. He had a mischievous face and a keen ability to spot the passenger who was avoiding paying his fare. With the agility of a gibbon, he clambered up and down the sides of the truck, and over and into the cab through its windows, while we were moving.

It was for most of us our first truck ride in South America. We learned fast.

Divine Light

The first thing we learned was that, tor the truck-rider, almost everything depends on the place he manages to corner for himself in the back. There are one or two key sites. In these, a comfortable and secure nest may be built. At the other end of the scale, there are sites where the occupant is in danger of his life - from shifting cargo or from being lurched overboard. Most other positions lie somewhere in the purgatory between these two extremes.

There is no standing upon courtesy or seniority in getting the best positions. Nor must you think that, once won, territory is secure from invasion. Fellow travellers will edge (or pounce) into unguarded places; and, whereas a little extra consideration is given to mothers with babies, there is no precedence for women (as there might be in Europe) or for men (as there might be in Africa) or for the elderly.

The elderly seem to be more than capable of looking after themselves. There was an old man on our truck who was a demon at this.

He was a farmer; and from the moment we set off he talked of money. His money. How much he had, how much he expected, and how much his property would realize were he to sell it. We pretended not to understand him, so after a while he pushed his way sideways along the uncomfortable bench towards a sheltered corner where, with her knees up, the middle-aged lady was dozing gently.

Her dress was the typical mixture of squalor and finery: mauve skirts and pink calico knickers (winter-quality). The wily old farmer, under cover of an animated inventory of the entire contents of his farm and their approximate value, moved in close to her, pushing one of the drunken Indians off his perch.

Like his fellow farmers the world over, his clothes defied our era's preference for 'casual-smart': they were formal rags, and filthy. 'Take a look at my spectacles,' he was saying, to nobody in particular. 'I had them made in Lima. The best. Very expensive. I think I have the receipt with me ...' and he fumbled through the pockets of what had once been a blazer to produce a grubby stack of dog-eared papers.

All the while, he was inching towards the middle-aged lady. But it was not passion which drove him. It was an ambition to share her comfortable corner, which she showed no sign of yielding, nodding boredly as he barked on, his metaphorical finger - like farmers everywhere - poking you in your metaphorical chest as he spoke.

'Of course I do not need to travel by public truck. I have my own truck but my son-in-law is running it down to Lima this week. Bought it for 300,000 intis. I think I have the receipt ...' He observed that she had nodded right off to sleep. Stealthily he shifted his old buttocks off the hard bench onto the cosy patch just next to her, in one swift movement lifting her little granddaughter off the space the child had occupied and depositing her on to the nearest thing - Ian's knee. So

Inca-Kola

quickly was this done that she did not even properly awake. Ian, mildly surprised, took the new arrival with his usual good nature. Our Peruvian yeoman carried on talking.

'... And I'm expecting my son - the eldest one, in the 300,000-m^/ truck - and he's worth a lot more himself- and that's without counting his wife's fortune - back in Chiquian with the new kerosene refrigerators. I reckon they'll fetch 20,000 intis each. Maybe more. What do you think?'

This was fatal, for the lady opened her eyes momentarily, saw him all but snuggled up against her and realized what was taking place. She did not hesitate. One powerful knee emerged suddenly from a sea of petticoats, knocking him violently sideways into an oil drum. He resumed his place on the bench, wordlessly. The drunken Indians laughed.

Meanwhile, the little girl, Lis, had awoken to find herself on a strange lap: the lap of a huge creature she had never seen before with fair hair such as she had only seen in pictures or at a distance on tourists, speaking a language she could not understand.

As if it were all the most natural thing in the world, she started talking to him, babbling away non-stop, careless of the fact that he appeared neither to respond nor understand. His broad smile was enough. Her name was Lis, she told him, and she was four.