Lymington

1975

From a deep sleep to panic: Christ, she’s aground on the reef again! Struggling from my bunk on legs that will not respond, I hear a baby’s cry and a man’s soothing voice, speaking in a language I cannot understand. Trying to pierce the gloom through sweat-filled eyes, I realise I am no longer aboard my sinking boat, but bed-bound in a small white room. Moonlight through a window touches wall-mounted posters about pregnancy before outlining rafters that disappear into blackness. Then memory floods back.

The population of Tutóia, a small fishing village on the Brazilian coast, had increased that day with the birth of a child howling its first protest at the same moment that a wreck of a man lay near to gasping his last. I had been half carried, half dragged from my boat and into their hospital, blister-faced, with feet infected and groin swollen. Sailing, I had once read, was a peaceful pastime punctuated by moments of extreme excitement but after my experience on the reef a week earlier ‘extreme excitement’ seemed the ultimate in understatement. As to those pregnancy posters on my wall the only thing I’d given birth to was a yacht called Solitaire or, as she was registered, Solitaire of Hamble.

She was conceived in South Africa towards the end of 1968: before this I had spent two years working as a radio engineer in South Yemen where I had taken to golf. But knocking little white balls over the desert held no future and I had flown to South Africa to practise my newly-acquired skills on grass, which led first to employment by an electronics company and then, indirectly, to sailing. One morning I wandered along Point Yacht Club’s jetty in Durban where cruising yachts from all over the world had come to rest, colour splashing from their fluttering flags, and was struck by their freedom. They were not shackled to land by chains whose links were forged by careers, mortgages and fashion: their mooring lines were but spiders’ webs so fragile that they could be broken on a whim or a wind’s whisper. Suddenly I wanted to throw my arms wide and scream at the heavens, ‘YaaaaaaaaHoooooooo!’

But an Englishman of course doesn’t do that sort of thing, not at ten o’clock on a Sunday morning, not in Durban.

I gave thought neither to sailing nor to the vessel itself, simply appreciating that a boat could be both home and transport for self, suitcase and a set of golf clubs from A to B at minimal cost. Early 1969 found me back in England with only £2,000 to my name, a sum that was hopelessly inadequate for the sort of boat I coveted. So I took a contract in Saudi Arabia as an aircraft radio engineer and pushed my savings up to £4,500, only to return home to yet more inflation. At this stage I met a young English couple just back from two years’ sailing in the Mediterranean, who were now off around the world in a beautiful 45ft sloop. Believing them to be experienced I considered myself lucky when asked to act as crew, but we motored most of the way to Gibraltar and I can recollect no single incident or experience that proved useful on subsequent voyages, unless it was a strong desire to sail alone. I would make blunders but they would be mine rather than someone else’s: they were certainly not the yacht’s and never the sea’s, whose roar can burst an eardrum, but, when it comes to excuses, is profoundly deaf. No, I would sail single-handed. Alone.

After another stint in Saudi Arabia the beginning of 1973 found me possessed of the respectable sum of £8,500, by which time the price of the type of boat I wanted had jumped to more than £12,000. Then I chanced on an advertisement in a yachting magazine: ‘Come to Liverpool and build your own Nor-West 34, hull and deck, £1,300’.

I promptly made an appointment, and one cold morning in January drove through Liverpool’s leaning dock gates, easing the throttle to prevent tyre slip on the oily cobblestones. The dock’s stagnant waters housed a waste of pans, cans and blackened bottles and on the adjacent rusty railway lines weeds flourished. A mouldering brick building, about 900 x 90ft, with a high sloping roof showing gaping holes, was the boat builders’ headquarters. Two modern cars, parked by high sliding doors, hinted of better things to come inside.

I edged mine alongside, wondering whether to brave the drizzle that was turning to rain. Making a dash for the doors, I grabbed the padlock and heaved. Nothing happened. Minutes later I was still attempting to get in, only now I was being tried out for Arsenal and taking running kicks at the door. All I wanted was to force my way inside and tell them what they could do with their stupid boat.

A polite cough as an immaculately-dressed man emerged from a side door. ‘Mr Powles? We’ve been expecting you. My name is Keith Johnson, managing director. This way, please.’

And he escorted me into this derelict slum as if it was a Hilton Hotel. Inside were two enormous plastic tents. ‘This is where we lay off the hulls: the plastic prevents dust falling onto the resin.’

All was spoken in a serious voice, despite the heavy rain still soaking us. We moved further into the building in search of a drier spot where, in Nelson’s time, the floor might have been of stone and was now, after centuries of dust, but a puddled dirt surface.

The managing director still rattled on: ‘We have two plugs for building the hulls, one used by the company, the other for do-it-yourself people. The company can build a hull and deck for £2,500. Have a look: as it happens a couple of our self-building customers are just about to remove the plug from their hull.’ With that he pointed to the far end of the shed where a crane hovered over the vague outline of a boat.

It was love at first sight. Instinctively I knew this I had to have.

‘What’s the specification, Keith?’

‘She’s a Bermudan sloop in foam sandwich and glassfibre designed by an Australian, Bruce Roberts. She’s 33ft 6in long, 24ft 6in on her waterline, with a beam of 10ft 6in and a draft of 5ft 6in. Classed as a cruiser racer she can sleep up to seven people.’

She would have more room than the Contessa 32 that I had seen at the London Boat Show but could not afford, but had the same clean lines as the Contessa with a fine entry, keel and skeg. Though I could not see my wanting ever to sleep seven people aboard her.

‘What will she cost complete?’

‘Around £4,000 to £5,000, but that’s up to the individual. We charge a basic £1,300, which includes the use of the plug for a month, a female mould for the deck and all building materials, a set of plans and fitting-out instructions and free rent for a month. After that there’s a small charge if you remain longer.’

I would need a place to live. ‘If I bought a small caravan, could I keep it alongside the hull?’ I asked. A quick nod to that. ‘If I gave you a cheque for a deposit today, when could I start?’

There was a pause. ‘It’s short notice but you could start in a month’s time.’

I wrote a cheque for £400.

The womb that was to develop Solitaire’s embryo would not be safe and warm, but she could still be a beautiful baby and with my £8,500 I would give her the best start I could in life. On the 80-mile drive back to my home town of Birmingham I considered two priorities: first I had to buy a caravan, second I would need help for a few days.

Having bought a second-hand caravan for £200, I arranged for a school-leaver to spend a week with me, contracting to feed him, to take him to the cinema once, and to pay him £10 in wages. A couple of home-town mates agreed to spend a long weekend helping me to fibreglass in return for a slap-up meal and all the beer they could drink. Ken Mudd and Tony Marshall were both quality control engineers, Ken with British Leyland, Tony with Lucas Electronics. Ken I had met when I worked on guided missiles after returning from Canada in 1956 following the breakup of my first marriage. Tony came on to my scene in 1970 together with his wife, Irene, and their two lovely blonde daughters: their home was to become a workshop and a haven where I was always welcome.

The plug, or former, looked like an inverted hull built of wooden laths with half-inch gaps. While upside down, sheets of polyurethane foam (up to 3 x 4ft and half an inch thick) are sewn onto it, using a forked ‘bogger’. String is forced through the foam and between the laths, forming a loop into which nails are placed. When tension is applied the nails prevent the string pulling out, forcing the foam hard against the plug, much like a bobbin in a sewing machine.

The building of Solitaire, as I had already named her, went to schedule. After nine days, thanks to the help from one boy and two friends, the hull was covered with rough fibreglass, which left three weeks of my month for the miserable part – screening and sanding. Talcum powder and resin are mixed to form a paste, then a catalyst (hardener) is added with which to plaster the rough hull.

For smoothing I hired heavy industrial sanders with vacuum attachments but white dust flew everywhere. I had to dress in overalls, taping the cuffs and trouser bottoms, and wear a face mask and hat. Ghost-like figures would move as if they had fallen into flour vats, self-raising puffs for their feet or shimmering haloes round their heads, careful never to leave the building in their disguise by night lest the local people be diminished by cardiac arrest.

As the weeks passed the weather warmed and more people started building. The shed became a village community with its own characters: some, like driftwood, bumped alongside briefly, leaving but a faint impression before disappearing. Others would weave themselves into the fabric of my life with acts of kindness and consideration. I would make my own voyages and have my own moments of glory but without such friends it is difficult in retrospect to see how.

Stan turned up one morning in a 20-ton tipper to build his hull. Until then there had been no facility for removing the mountain of rubbish in the middle of the floor. The rats that infested it grew tame, no longer scurrying away at the approach of a human but stopping to clean their whiskers, lift a paw to their forelocks and give an apologetic half smile, as if to say, ‘Morning, gov’nor.’ This always started my day well, for I would nod and even consider raising a hand in the weak-wristed wave favoured by royalty.

The yacht builders arranged for a tractor to load our mountain onto Stan’s truck, to be carted away when he left. From then on we threw our waste directly into his lorry. At the end of ten days, Stan’s hull looked great. He and his father had worked hard and had benefited from the experiences of previous builders, even using steel rollers to smooth out the raw fibreglass. Glittering, it stood there, still wet, waiting for the catalyst to dry and harden it. Next morning it was still golden, gleaming and wet, but streams of yellow syrup were falling from its edges into gooey pools. After a week of trying everything including heat and nearly pure hardener, it was finally agreed that the resin was faulty. Since Stan had already lost three weeks’ work with his truck, he asked for a replacement hull already brought to the same stage as his own. The company offered to supply a man and materials, whereupon Stan rebelled. Next day his tipper had gone, having upended our mountain on the floor, bigger than ever. Only the rats were smiling.

Bing, a scientist, was helped by two teenage daughters. His keel had been formed along with the hull and was a box section some 8ft long, 3ft deep and 9in in the middle, tapering to rounded ends. This box took two tons of ballast which would prevent the yacht, with sails raised, from flopping onto its side. In theory you could stand the boat on its nose, roll it upside down, or simply drop it from an aircraft and it would still bob right side up. There was a disadvantage: if you ever put a large hole in the bottom of your craft, your life savings would go down like a brick.

At this time we could use two materials for the keel: iron or lead. The first to build a hull (Berny and Vic) had made a plaster mould of the inside of the keel from which a local foundry would make a 2-ton iron casting for £90. Lead, which took up less room and gave a lower centre of gravity (thus making for a stiffer boat), would have been preferable, but the price was more than double – £250.

Bing called a meeting and described how we might use the non-active atomic waste, heavier than lead, which the British government was dumping in the North Atlantic. Bing thought we might get a load cheap. We were all keen on the idea until someone asked, ‘Since we will be walking over the stuff, what would happen if it became active?’

Without hesitation Bing replied, ‘It would have the same effect on your sex life as the loss of your testicles.’

As I hurried away I said to a newcomer, Rome Ryott, ‘I don’t mind risking one but not both.’

‘I’m risking neither!’ said he.

Rome had arrived in my life with dash and style, driving directly into the building in a sporty red Capri, complete with beautiful blonde passenger. He was tall, broad-shouldered, narrow-hipped and as he walked in with quick, bouncing steps, full of purpose, I fully expected to hear James Bond theme music. His first words were not ‘Anyone for tennis?’ as I had anticipated, but enquiries about the boat he was due to start building the following week. His soft, educated voice had a Wodehouse stutter assumed to give him time to choose his words. He became my closest friend.

The yacht’s deck was made from a female mould, a process that took only a few days. The principle was much the same as housewives have used for years to turn out fancy jellies. First you coat the mould with wax (release agent) which in turn is given a heavy coat of paint (gel coat). The laying up, as for the hull, starts with very fine lengths of fibreglass, looking much like tissue paper, and is built up to heavier grades, with a layer of woven rovings. Water is then forced between the deck and mould to break it loose, and there is your completed deck, already smoothed and painted.

One Sunday night at the end of his month, Rome, packed and ready to set off, called at my caravan. ‘I have to be at work tomorrow morning,’ he said. ‘Since I’ve just had one leave I’ll only manage to get here for long weekends to build the deck. I... I... was wondering if I gave you a hand to build your deck, would you help me to get mine finished?’

‘Sure, Rome,’ I replied. ‘By the way, what do you do for a living?’

‘I’m a pilot in the RAF,’ he answered.

From that moment I knew Rome would not figure as one of my pieces of driftwood: it was perhaps because I had always wanted to be a pilot but more, I suspect, because with his quiet unassuming manner Rome accepted me for what I was, ignoring my background, lack of education, working-class accent and financial standing. Rome was someone I could always look up to, yet he never once looked down on me. His father had been a silent movie actor (hence the son’s exotic name) who had died leaving a widow, Grace, with two young children, Rome and his sister Terry, to bring up. After a short period in the Merchant Navy, Rome joined the RAF, where he learned to fly first helicopters, then jets. Interested in sailing since an early age, he had already owned several boats, which he changed regularly along with sporty cars and even sportier girlfriends.

I was born in Birmingham which, for an Englishman, is about as far from the sea as you can get, on October 24th, 1925, and was brought up there, living in a small terraced house with parents and young brother, Royston. We were a normal working-class family, never well off, my father employed as a foreman at the Rover car factory. During the Depression the rent man would bang on the door while we cringed inside: they were terrible years for my father, a proud man who stood on his own two feet and never failed to pay his debts.

The Second World War broke out when I was 13, and the following year I went to work in an aircraft factory as a machinist on Pegasus aero engines. But my ambition was to be a pilot. As a boy I had spent hours at the local airfield watching Tiger Moths, Hawker Hinds and Gloucester Gladiators drop over the boundary fence. Aged 17 I joined the RAF, not as a pilot but as a wireless operator/air gunner.

Having completed the training I became a sergeant but the war was over before I could join an operational squadron. My service career ended running a station laundry in Italy, with 12 lovely young women to look after – an occupation in which I upheld the finest traditions of the British Empire but for which, unfortunately, no medals were awarded. Since then I had had many different jobs, in many countries. In my time I belonged to four skilled unions, only because I had to in order to work. I had had my own businesses including a garage, a haulage firm and shops. I was always a loner, never feeling I belonged.

My introductions to the opposite sex started with Nancy in Crewe, courtesy of two American Eighth Air Force bomber wings. As I had just been promoted to sergeant Nancy came in the form of a celebration and I shall always remember her with gratitude for her understanding, kindness and tuition. ‘Navigator to pilot, left, left a bit. Hang in there old buddy... bombs awaaaaaaaay!’

I married two charming ladies and was divorced from two charming ladies. No children came from these associations, only cocker spaniels whose custody was fought over with more bitterness than the D-Day beaches of Normandy – the battles were always lost when it was pointed out that I was a wandering soul, unable even to provide a proper home for them.

Brian Gibbons reached Liverpool to build his boat – by Jaguar. He owned a factory in the Midlands (not far from my home town). He was a boss who wasn’t frightened to get his hands dirty and, without doubt, the finest all-round engineer I have ever met. Married, in his mid-thirties, his friendly, rugged face was topped by a mop of unruly hair. His clothes, like his hands, were likely to show oil or grease stains and he spoke with assurance and authority in a Midlands accent.

Brian had bought a finished hull and deck and would turn up with lumps prefabricated in his garage or works which slotted precisely. He overtook us all: I was for ever seeking his advice which he seemed to encourage, mulling over problems with the same sort of concentration some people show for The Times crossword. It was never long before he would return, a stub of pencil and scrap of paper in his hand. ‘This is what you do, our kid.’ And you had your answer.

Once the plug was removed, the hull was placed in its cradle. Then 3in channels were chiselled out of the foam to form stringers and bulkhead recesses. The plans called for three layers of 2oz fibreglass to be laid up inside the hull but I went way above this specification, trying to build more strength into the boat. As bulkheads were fitted and glassed into position we started to use new terminology: we would be working in the forward compartment, the heads, or main cabin.

After completion the decks would be lowered into position with a 2in lip running around the outer edge until it came flush with the top of the hull. It was then through-bolted, and later capped with wood to make the toe rail. The inside corner would be glassed-in to give more strength and make it watertight.

Brian asked for layers of fibreglass to be left out as he wanted a lighter, faster yacht, but he put strength back by running two Iroka beams along each side of the boat, under the deck, which were then glassed in position. He also put a third beam across the rear cabin bulkhead. Through-deck U-bolts took the standing rigging.

I followed Brian’s example despite the fact that I had been adding weight instead of reducing it. By this time people were saying I was over-building Solitaire, using backup systems to back up systems but I knew she would have to look after both of us until I could learn the ways of the sea and sailing.

If you asked the driftwood what they remembered about me, they would probably reply, ‘Leslie? Oh yes, he was the one who cut a blooming great hole in the bottom of his boat.’ In fact it was 9in wide and 4ft long. I had never liked the skeg, which was hollow, and, when banged with a fist, would vibrate. I spent a weekend in Tony Marshall’s garage building a replacement of Iroka, a modification which one day was to save Solitaire – and me. The size was increased to allow 10in to extend into the hull for bracing with a hole drilled ready to take the stern tube and propeller shaft.

For a few days the boat sat with a gaping hole in her bottom. To lifted eyebrows and inquiring looks, I would merely say, ‘Mice.’

In June my mother was taken to hospital which meant that I had to return home. I managed to find a good position with Ken Mudd as a quality assurance engineer for British Leyland. Solitaire was moved 80 miles overland into a field where I fitted her out, buying unplaned planks of Iroka for her interior. Most of the work was carried out with the help of an old friend, Tony Marshall, who had started out as a carpenter. Len Westwood, a foreman motor mechanic at British Leyland, helped to fit a new 18hp Saab diesel engine.

When the time came to install Solitaire’s ballast, I bought 2 tons of scrap lead but could not decide how to pour the casting. I considered using an old bath as a melting pot, but the snag was manoeuvring this lump into the boat now that her deck had been fitted. When in doubt I did what I always did – phoned Brian Gibbons. He had got over this problem by building an adjustable die with which you could make ingots to suit the shape of the keel. Having borrowed it I spent two days in Tony Marshall’s back garden where we cut a 32lb gas bottle in half for use as a cauldron. For heat we used coke with a couple of car air blowers. The resultant 80 castings fitted to perfection and with a few gallons of encapsulating resin the job was completed.

Solitaire began to show her beauty and was ready to be christened in seawater. A government agent had visited and presented her with a British birth certificate. She was painted and antifouled; mast, boom and rigging ready for fitting.

Although Rome had been stationed up north we kept in contact with weekly letters and the odd visit. He already had a berth in Lymington, his home town on the south coast. In March 1975 he took his yacht there, so I went along to lend a hand and to learn the ropes. There I was introduced to his mother, Grace, a fitting name for such a lady with her easy smile and quick laugh. Born in South Africa, she still had tinges of the accent. I met her lovely daughter Terry and Terry’s husband, Martin Maudling, son of the former Chancellor of the Exchequer, which started another lasting friendship.

By now I had reached the stage where people began to say, ‘It must be great to own your own yacht and sail around the world. I’d love to do the same but...’

‘But’ is always the crunch. Invariably it would be followed by ‘I’m still paying the mortgage’ or ‘the wife’s not keen’ or ‘the cats have had kittens’. If people were honest with themselves, they would admit they led a contented life and had no reason to change it.

As for me, I was 49 years old, had a well-paid, secure job, with no possible chance of finding another if I gave it up, but I had no buts. The dream I had had in South Africa six years earlier was stronger than ever so I surrendered my safe future and moved Solitaire to Lymington where she was immersed in seawater and baptised.

The launch went without a hitch, Solitaire bouncing like a beautiful baby, just above her waterline. The father, however, was to find himself in embarrassing situations over the next few months in trying to understand his child.

John, the dockside foreman, and his lads had gently lowered her into the water and stepped the mast. Only one end of the rigging wires had connectors, which had to be secured to the tangs on the mast. Everything was held in position by the halyards. Later I would cut the stainless rigging wires to length and fit Norseman connectors... I had been telling John how I had built Solitaire, impressing everyone with my plans to sail around the world singlehanded. Then I asked where I could park my boat. John pointed to a berth less than 50 yards away.

‘Would you please take us over?’ I asked.

He was busy, he replied, and since there was no wind or current I would have no problem. ‘Slack water’ was what he actually said. I then explained that I had to check the engine, look for leaks and change my socks. When I finally ran out of excuses, I admitted I had never berthed a boat or tied one up in my life. We chugged over at a third of a knot to catcalls, cheers, and cries of ‘Bon voyage’ and ‘Send us a card from Cape Horn’.

Two days later I was in trouble again. I had completed the work on the rigging and had fitted the boom when a stranger asked, ‘When are you fitting your kicking strap?’ What on earth was he talking about? Suspecting that he was pulling my leg, I gave a vague wave of my hand and said, ‘Maybe tomorrow’. The solution seemed easy: go to the chandlery and buy one. Next morning I was waiting for them to open.

‘Good morning. I’d like to buy a kicking strap, please.’

‘We don’t have any made up.’

‘When will you have some made up?’

‘Well, we never make them up, we sell the parts.’

‘Fine, I’ll buy the parts.’

‘What size, sir?’

‘What do you mean? I’ll take average.’

‘How much rope do you need, sir?’

‘Oh, a few feet.’

‘Don’t you think you should measure the length you require... sir?’

‘Right, I’ll be back.’ As I left the shop I had a brainstorm. Back in the marina I found the first yacht with someone aboard who looked intelligent.

‘Hello, that’s a fine craft you have there. And a nice kicking strap.’

A puzzled look. ‘What are you on about? Mine’s in the locker.’

Rome arrived to help me buy the necessary pulleys and ropes to put tension on the boom – the kicking strap. After that he took Solitaire into the Solent to supervise my first faltering steps. She handled better than his own yacht, he said, with less weather helm, which might be due to my using lead ballast instead of iron. My sailing, however, was less impressive. I took over after Rome had shown me how to set the sails for different points of sailing. An hour went by with Rome becoming very quiet. Fine, I thought, he’s taught me all I need to know. Now I can pop off round the world.

‘Nice day, Rome.’

‘Not bad, we could do with a bit more wind.’ (We were becalmed at the time.)

‘Er, that’s it then, my old mate. I’m all set to go, eh?’

‘Well, Les, I’d give it a bit longer.’

‘How much longer, Rome? A couple of days?’

‘Maybe a year.’

Later, when he had jumped in the dinghy to take pictures of my sailing by, I said, ‘Rome, just one quick question before you paddle off. How do I stop the bloody thing?’

‘Les.’

‘Yes, Rome?’

‘Make it two years.’

The following week I took Solitaire out alone, a single-hander for the first time. I had given much thought to this, deciding that the cautious approach would be best with the engine on slow tick-over so that if I bumped into other boats only small pieces would be removed. I realised my mistake soon after leaving the pontoon when wind and current revealed how quickly Solitaire could move sideways. Craft that minutes before had seemed deserted became festooned with happy, smiling yachties joyously waving fenders, old truck tyres... and boat hooks. Out in the less restricted Solent, things went better until I hoisted the mainsail and genoa. There was a tangle on the genoa winch due to my failure to feed its sheet through the deck block, and the mainsail was not filling properly as I had forgotten to slacken the topping lift. Thereafter I had no other problems. She would sail close to the wind unattended, even allowing me to make a cup of tea!

The mechanics of sailing were never to trouble me, but I deeply regretted not having had the opportunity to start in dinghies as a boy, to learn to do things correctly from the start. Bad habits take years to break, whether swinging a golf club, driving a car or sailing a yacht. I had some help in that I had been born a coward. I disliked arguing and would always walk around people when possible. As a boy I had stood in my school playground with blood streaming from my nose and soaking a torn shirt, hands open by my side. The bully had continued to slap my face, egged on by the jeers of the other children. It wasn’t that I was afraid, just that there seemed no point in fighting. Only when I realised I was trapped did my hands become fists.

I approached the sea in the same way, hands open. I had no wish to fight the sea, to claim false achievements, to feel anger. At the first sign of the sea’s disapproval I would lower my colours and drop sail: only when Solitaire’s life was threatened would I fight back. The sea was far stronger than any ship so I had to always try to live with it, hands open.

I stayed out a couple of hours, anxious then to return to the marina to try out a new theory. My approach to berthing had been quite wrong; far too slow, it allowed outside elements to take over. The marina berths consisted of long pontoons, both sides of which had fingers to form an H, each U-portion taking two yachts. Should you fail to stop when entering your berth, the bow of your boat slowly rises up the pontoon before sliding gently back into the water.

I went down the long line of boats at approximately 5 knots in a graceful curve, sweeping round at the last moment to line up on our berth. A boat’s length away, I pulled back on the pitch control lever, which provides forward, stationary and reverse drives – and it jammed. In the next few seconds I broke several world speed records, none recorded. When I opened my eyes it was to find Solitaire lying alongside her berth docilely, indignant at the delay in having her lines made fast.

Later a twit arrived. ‘I say, old boy, everyone was concerned by your departure, but jolly impressed by your return.’ I would spend much time wondering whether he was serious or sarcastic.

The main hold-up to our departure now was the lack of self-steering gear. This had been a long drawn-out affair starting in Birmingham a year before. Three leading manufacturers had quoted roughly £250. After Rome’s remarks about Solitaire’s lack of weather helm, I felt she could be steered by any of these gears, and settled for one that was compact and neat with a direct drive onto a balanced rudder. This was the beginning of a long association with Hydrovane, one I have never regretted. Indeed, the independent rudder would one day save Solitaire.

Group Captain Rex Wardman turned up at crack of dawn one morning soon after my arrival in Lymington and banged loudly on Solitaire’s side.

‘Come on, Rome, you lazy devil, time to get up.’

I stuck my head out of the hatch. ‘It’s not Rome, it’s Les, and you’ve got the wrong bloody yacht.’

Rex was a little shorter than me, and a little older, having joined the RAF in the 1930s to fly many of the aircraft I had watched and admired as a boy. A jolly man, he lived life to the full, brushing problems aside with logic and a flick of the hand. As an experienced sailor Rex had been one of the first to take a berth at Lymington. Over the coming years it would be hard to count the number of times he and his wife, Edith, were around when I most needed them.

On this occasion, after inspecting Solitaire, Rex muttered, ‘It seems hardly fair to keep buying yachts when some people go into a field with a bucket of resin, a roll of fibreglass and build their own.’ The final insult, on seeing the piece of old wood I was using as a tiller, was ‘I don’t think much of that.’

He enforced the point by taking a kick at it and left me thinking that that was the last I would see of him. Minutes later he staggered down the jetty with two beautifully laminated tillers on his shoulders.

‘I’ve changed my yacht to wheel steering. Give one of these to Rome and keep the other for Solitaire.’

Without even waiting for thanks, he was off again.

Rex took me racing in the Solent a couple of times, not that I really enjoyed it. I found the sport a bit hair-raising, especially the starts, watching all that money being thrown about with seeming abandonment. On one occasion Rex had a beautiful crew member whom I assisted in the galley, and by the end of the day felt I had made a fair impression. Helping her ashore she belched in my face. ‘Leslie, how could you?’ she said and stalked off with another crew member, which just about summed up yacht racing for me – expensive, attractive and often with nothing but a belch at the end.

By August 1975 time was running out and so were funds: with berthing fees of £10 a week, only £300 remained in the kitty. Solitaire was still uninsured and the risk of damaging another yacht due to my lack of experience was worrying. Soon it would be autumn with a bleak English winter not far behind, making sailing difficult. Although I had a reasonable amount of food on board, I had no accurate timepiece, liferaft, flares or transmitter. Charts, too, were in short supply, along with navigational books.

Rome was still insisting I wait another year, while Rex Wardman was threatening to break both my legs if I started on a world cruise so ill-prepared. But despite shortages I wanted off, to have Solitaire to myself away from prying eyes and to learn our lessons together in solitude, listening to sounds we had not heard before, riding on waves, skirting their edges, gliding over peaks, surfing down valleys, seeing over horizons, controlling our own destinies.

I had no desire to be one of tomorrow’s people: ‘We’re off tomorrow when we’ve bought our new sail’, ‘We’re off tomorrow when we’ve painted the topsides’, ‘We’re off tomorrow when we’ve bought a bigger boat’. I foresaw the final excuse: ‘We’re off in a hearse. We ran out of tomorrows.’

I had wanted to start six years before, not tomorrow but yesterday. Whenever asked about my first port of call, I would say, ‘Barbados’. To avoid technical or navigational questions I would become flippant. ‘I’ll potter down the middle of the English Channel and when 300 miles into the Atlantic, I’ll turn sharp left and sail between the Azores and Portugal. Then I’ll fork right onto Barbados’ latitude of 13°20´ and I’ll stay on it until the island appears over the horizon.’

At that time I believed celestial navigation to be beyond my limited education, a belief which goes back to the early days of sailing when captains hugged the secrets of navigation to themselves, fearing that mutinous crews might take over their ships. The fact that the young couple with whom I sailed to Gibraltar took no sights, despite having a first class sextant on board, did nothing to rid me of my apprehension. Rome showed me how to correct for sextant error but then I made the mistake of asking him to explain the formula. There is no need to know this, any more than there is to grasp the working of a car’s gearbox: simply accept that it works and try to understand the rules. To learn to use a sextant takes less than an hour, a noon sight for latitude no more than a day. Yet I was foolish enough to sail without this basic background.

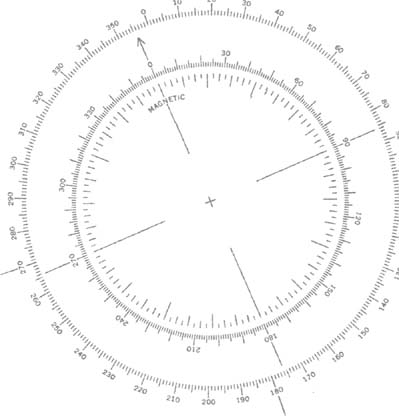

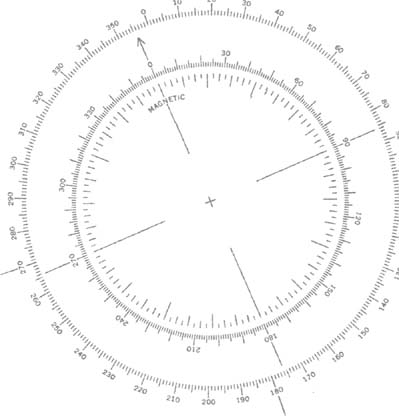

I had neither timepiece nor navigation tables, so there was no possibility of my carrying out sights for longitude. I possessed a small portable receiver but this had only long and medium waves with limited range and was unable to pick up BBC overseas broadcasts for time checks. My navigational equipment consisted of charts, compass, Walker trailing log (to register distance covered), Seafarer depth sounder, and a Seafix radio direction finder (one of my main hopes for safe navigation since I remembered my morse code from RAF days). A major mistake was not to carry the Admiralty Book of Radio Signals, which gives the stations around the world: instead I had Reeds Almanac, which only printed European call signs. However, Reeds, with a £10 plastic sextant, would give the information for sights for latitude. With my limited sailing experience it would have been more sensible to have studied two or three English ports, using daylight, tides and weather to coastal hop.

Ken Mudd and his family came down to spend the last week with me. Ken, a born do-it-yourselfer, fitted gas bottles, radar reflector, hatches, battery and goodness knows what else. At the end it seemed only fair to take him and his family for a sail, as in any case I wanted to try out the newly-fitted self-steering gear. However, Ken gave me no chance of doing this, seizing the tiller as soon as we were under way and refusing to give it back, glaring down at me from his 6ft 2in at any intrusion on his new-found pleasure. He managed to chalk up one first with Solitaire when he ran us aground.

We had dropped sail and were motoring back to our berth. ‘Stay just this side of the black markers,’ I had instructed. ‘Watch out for the ferry’. I was fiddling with the self-steering gear again, leaning over the stern, when...

‘Les, we seem to have stopped.’

‘You stupid clot, Mudd. You’ve put us on the mud. Where’s the marker?’

He pointed to a blackbird sitting on a post. Too late I remembered the day I had first met him. We were standing a few feet from a works clock as big as a barn when he asked me the time. Ah well, no one’s perfect. With a bit of jumping about we soon got off. Ken and his family returned to Birmingham that night, not out of embarrassment but simply because it was the end of a holiday. It would be nearly three years before I saw him again.

I was passing the point of no return: my old banger was sold, there were last-minute calls to my parents, to Tony Marshall, Irene and their children, Tracy and Sally, with a few belated words of thanks for all their kindness.

By the night of August 17th, Solitaire was just about ready to sail. Covers were off, and the number one genoa and working jib hanked onto the twin forestays, the Avon dinghy half-inflated on deck ready to act as a liferaft. Grace Ryott came down to wish me well with a box of chocolate bars. Anne and her daughter, Susan, invited me aboard their boat for a late supper, as they had done so often before. This time there was too much to do, but I was grateful for their help in turning Solitaire so that she was pointing in the right direction (I didn’t want her kissing the other yachts goodbye!).

Monday, August 18th, I showered and mailed a dozen postcards. A kiss on the cheek from Anne and Susan, a final wave. Solitaire and I were off around the world, unfortunately not to fame and fortune but ultimately to laughter, pointing fingers and cries of ‘You’re the one who finished up in a maternity hospital.’