Tutóia – Fatu Hiva, Marquesas Islands

November 1975 – May 1976

Slowly we motored through the watery forest into a nightmare of shallow brown waters, waves breaking over the sandy islands that threatened our passage. I raised sail, trying to lift the keel by heeling but without success. Ahead I could see the black marker buoy that had greeted our arrival, towards which Solitaire made her way, picking her steps as though walking through a minefield, with nothing showing on the echo sounder. She lifted and dropped heavily on hard ground, her mast shuddering, and I was promptly and violently sick over the stern. Slowly, so very slowly, we struggled to the buoy.

The sea was still brown but Orland had shown me on the chart in his office that if I sailed north I would soon find deep water. Moreover, I now had the two charts the fisherman had given me and a list of RDF call signs all the way to Panama. Although I had no harbour charts, the ports I was considering would be well-buoyed, with Cayenne, 650 miles away in French Guiana, the first.

The first 24 hours were nerve-wracking, what with gusting winds, choppy seas and the bilge pump packing up, thanks to a ripped diaphragm. Solitaire needed pumping dry twice a day so I made do with a bucket and sponge until I contrived a new diaphragm from some plastic ‘rubber’ left over from the seat covers.

My noon sight on November 19th, put us 22 miles below the Equator and as we made our first intentional crossing that night, the wind came light from the east enabling Solitaire to broad-reach contentedly for Cayenne, dozing along under main and working jib. I should have put up a larger headsail but relaxed with 80 miles a day, plus another 20 miles or so from the favourable current. My nerves steadied, the cool sea breeze refreshing my scarred skin. To celebrate crossing the Equator I dined on spam and chips.

As the days slid by the winds continued to decrease but I refused to fly more sail for I was enjoying this voyage too much. I found some flour in a plastic bag inside a box of sponge mix, and made my first-ever pancakes, spreading them with my favourite marmalade as the radio started to pick up delightful French music.

One morning I saw what I first thought was a low flying aircraft coming over the horizon, followed by another and another. As they neared, I could see they were modern fishing trawlers with their arms extended. All day, stretching from horizon to horizon, they streamed by Solitaire. With darkness they became a blaze of lights, making me think I was sitting on a main street. Then, like a body of soldiers, they turned together, headed out to sea and disappeared. A last arrival came scurrying by, late for parade. ‘Get a move on, you hoooooorible little man...’ I cried in my best sergeant-major voice. When he had gone we had the night to ourselves, and a French woman sang me to sleep with love songs.

On Tuesday, November 25th, Solitaire lay a couple of miles off Cayenne. I could see trawlers heading inshore but could pick up no RDF signal, although Paramaribo in Dutch Suriname was coming in loud and clear from 160 miles away and, since it had a lightship to help with the landfall, I decided to sail there instead.

We arrived late on Thursday and lay off, keeping the lightship in sight until morning. Although I had tried to hold our position, Solitaire had drifted to the north with the current and had to be forced back. Again the waters were chocolate-coloured but a clearly-buoyed shipping lane made navigation easy. A strong outflowing current slowed progress and as ocean-going ships were using the main channel, I pulled to one side, dropped sail and anchored for the night. Food was getting short so dinner consisted of a tin of mixed vegetables, salad cream and an orange, as did breakfast the next morning.

We arrived in Paramaribo fairly quickly and rode the broad river on a favourable tide. The port seemed prosperous enough, with clusters of docks housing fleets of shrimp trawlers, the town a mixture of old Dutch buildings and modern stores, a bustling fruit, fish and vegetable market on the dockside. Flags and bunting were everywhere as a week earlier Suriname had gained its independence from the Dutch. The harbour itself was spoilt by a massive cargo ship parked in the middle, upside down, scuttled by the Germans during the last war. I felt Solitaire shudder when she caught sight of it but I hastened to disclaim any responsibility.

However, I soon managed to get us in trouble again. I dropped the hook about 20ft from a structure of girders but was suspicious of Solitaire’s position in the fast current. If I attempted to lift the anchor again or she started dragging, we could find ourselves trying to climb over the top of the sunken German ship. On the girders, wearing green overalls and plastic helmet, stood a black man, looking for all the world as if he had been working on a New York skyscraper when it had sunk.

After my experiences in Brazil I knew you could work wonders with the odd packet of English cigarettes, so I waved a pack in his direction, making a diving and swimming action with arms, shouted ‘Amigo’ and waved him over. His eyebrow merely lifted, whereupon I increased my offers to two packs, still without joy. Perhaps he could not swim? The solution was easy: I would throw him a rope which he could tie onto a girder. I would then pull Solitaire over and he could lift the anchor while I steered. My throw was perfect, landing plumb at his feet at which he raised the other eyebrow. We both watched with interest as the current slowly snaked the rope back again. After three more perfect throws I grew despondent.

‘For Pete’s sake, will you please tie the rope to the girder,’ I cried.

To my surprise he picked it up and secured it. Roy turned out to be the dockyard foreman and spoke excellent English, Paramaribo’s second language, probably because the Americans run most things there. Roy took me to the Dutch manager who could not do enough. The structure Roy had been standing on was part of a dry dock for lifting prawn trawlers. Solitaire could be hauled out at the same time at no expense to me but I turned down the kindly offer, wanting to push on to Panama.

The only other cruising yacht in port at the same time belonged to a Frenchman, Stephen, who with his wife and young daughter was preparing to leave on the out-going tide when I arrived. I was invited on board to share their last meal before they sailed: steak, salad and bread washed down by fresh milk! They put me ashore with the last of the steak in a crusty roll. As I let go their lines, Stephen asked what my next port of call would be.

‘British Guiana,’ I replied.

Stephen’s mournful plea came back: ‘Oooooh, Leslie, don’t go there. Very bad people. You will be robbed.’

So I said, ‘Right, I’ll go to Trinidad.’

‘Oooooh, Leslie, don’t go there. You’ll be robbed.’

So I asked where they were going.

‘Grenada in the Caribbean,’ they said.

‘Right,’ I shouted, waving goodbye with my steak sandwich. ‘I’ll see you there.’

My stay in Paramaribo, thanks to my first real taste of American hospitality, was longer than expected. They were either visiting Solitaire or taking me to a barbecue party, the movies or whatever. I bought what tinned food I could afford, always looking for the cheapest buy which did not always pay off as I had to throw away a dozen tins of canned mackerel. The Dutch manager presented me with oranges and a sack of grapefruit. My last day in Paramaribo was spent chiselling through Solitaire’s cabin floor and reinforcing the cracked hull with fibreglass.

The 500 miles voyage to Grenada took eight weary days. The currents between the islands are strong and as Grenada had no RDF station and those available on other islands were weak, dead reckoning became paramount. The last two days brought heavy rain with bad visibility which cleared up at midnight on December 16th when a large black cloud appeared on the horizon with a star in the middle – Grenada with a house light high up in the hills.

At dawn I motored to St George’s main anchorage where I performed my usual party piece of putting Solitaire on a reef. To be fair I don’t think we should count this one as another yacht was coming out, leaving insufficient room for two boats to pass. Solitaire, the perfect lady, stepped to one side and we had virtually stopped when there was a crunching sound and Solitaire rolled from side to side, shaking her mast as if to say, ‘I don’t believe it.’

Instantly a flotilla of small craft, power boats, yachts, gin palaces, even rowing boats, tore out as if they had been awaiting our arrival, the air filled with flying ropes and people clambered over our decks attaching them to every conceivable place. Within minutes, Solitaire was swinging to her anchor, dazed by so much attention. Where, I wanted to know, had they been when I needed them in Brazil?

We had just got shipshape when I heard ‘Ooooh, Leslie’ from a dinghy racing towards me. ‘Ooooh, Leslie, I’ve been robbed,’ said Stephen, which had me in stitches.

The following night I was laughing on the other side of my face. Men would silently raft around the anchored yachts by night intent on robbery, so it was unwise to leave craft unattended. New arrivals were quickly made aware of the danger and, in turn, I had already warned another crew that day.

I had met David, an American, through his English crew member, and had been invited to his yacht Rolling Stone for dinner that night. David had built his boat in England before sailing across the Atlantic to pick up his parents and a girlfriend for a holiday. I thought Solitaire, anchored no more than 40 yards away, was safe enough since I could still keep an eye on her and, for added protection, fitted strings to the deck light switch and attached them to the sliding hatches. There was a good crowd on Rolling Stone and for a while I sat drinking in the cockpit, watching my boat. Finally we disappeared below for a curry meal although every few minutes I would pop my head outside to make sure everything was all right. Then Solitaire’s lights came on.

David and another large American, Tom, rowed me over. I thought the thieves might still be aboard but the hatch cover had been ripped off and every locker, drawer and door opened, including the oven’s. I would not have thought it possible to wreak so much malicious damage in so short a time. The engine’s instrument panel had been uprooted and the spare money I kept there stolen. My portable radio, clothes, tools and two torches had vanished. The ship’s papers, my passport and £80 in travellers’ cheques should have been at the back of my chart table, but they had gone, too. It was a kick in the crutch. I could sell my outboard motor, WC, even the stove, and still continue around the world but without a passport or ship’s papers, I was stuck.

I told David and Tom the reason for my looking so sick, whereupon they started pulling out the charts... and found my wallet with the papers and cheques which meant that I could leave for Panama in the morning after all! My visitors had kindly left my RDF sextant and compass and had also missed a camera. The police were called but showed perfunctory interest and I was still upset next morning, as if Solitaire had been violated. David suggested I hang on for a couple of days and tie alongside Rolling Stone for protection, and again Americans came to my assistance. Tom and his girlfriend, Karen, presented me with a large bag of food, claiming that it had been stored in the bilges too long and was going bad. On inspection I found a recent label from the local supermarket!

Christmas was but a few days away. David and his family were sailing to Prickly Bay, 6 miles along the coast, where it would be quieter, with less chance of being broken into, and Solitaire accompanied them, feeling that one violation in a girl’s life was one too many. I did not set off for Panama until a fortnight later but in the interim became friendly with more Americans, including Bill and his girlfriend, Dean, who had started on a world voyage but had been forced to give up the idea. Since they couldn’t go, they decided to help me on condition I wrote to them detailing my progress with pre-addressed envelopes they supplied!

One other thing the Americans in Grenada offered was advice: stay at least 20 miles off the Colombian coast and ignore distress rockets. Pirates were using them to attract unsuspecting yachts, then murdering the crews and using the craft for drug trafficking. Finally, take care walking the streets of Colon, even in daylight, as muggers formed queues to rob tourists.

Solitaire set off on January 10th, logged 1,124 miles and arrived on January 23rd, 1976. Sailing to Panama is like entering the neck of a bottle: trade winds that have swept thousands of miles across the Atlantic can become quite strong and compressed; steepbreaking seas build up but fortunately for us they were from the east and hence over our stern. I left Grenada with a comfortable Force 4 from the south-east but by the third day winds had increased and we were down to working jib only, breaking seas speeding behind us. At times Solitaire would find herself surfing on them: at others, unable to move fast enough, she would receive a firm pat on her stern, and would turn indignantly as if to say, ‘How dare you, sir.’

On one such occasion a wave shot a bucketful of water through the open hatch, soaking the cabin carpet again. Thereafter I kept the hatch boards in, closing myself below and emerging only to take noon sights for latitude, obtain fixes, or check sails, rigging and self-steering. Most of the time I spent reading the books Bill and Dean had given me and eating strange American foods including stuffed tomatoes, which I had never heard of!

The night of my Panama Canal landfall I panicked. As I had been warned to keep 20 miles off the coast, I played safe and doubled it, then when it was time to turn towards land, I had the Cayenne problem over again: I could not pick up the Canal’s RDF signal. However, call sign TBG came in loud and clear, indicating the island of Taboga lying at the Pacific end of the Panama Canal, and since it was in the right direction, I set course for it.

At about the time I had estimated, I saw the loom of a light in the night sky and made for the glow, which swung up and became two blooming great headlights. Pirates! Turning off my lights I started the motor to shoot off back the way I had come, only to find another set of headlights blocking Solitaire’s escape. At that moment I saw the Canal lighthouse flashing and made for it. Astern were two looms of lights in the sky; I’m sure now they were fishing boats using their lights to work by. Maybe I scared them more than they scared me. Maybe.

I waited for daylight before easing through the breakwater where, after anchoring on mud flats, an American Customs launch came over and gave me the good news that I would have enough money to pass through the Canal. It would cost only £30, half of which was a deposit and would be returned later. That was not my only piece of luck: I also received my first letter from Rome who, as an ex-merchant seaman, knew I had to pass through the Canal. I had reported all my blunders and how Solitaire kept getting me out of trouble, to which Rome replied that, despite so many mistakes, at least I was making them only once. I wrote back immediately... omitting to mention the reef in Grenada!

To arrange our transit I moved Solitaire into the Colon Yacht Club, one which does not encourage you to linger as they double their prices every three days to make room for new arrivals. You can stay on the mud flats free of charge, but from there it is difficult to arrange for a pilot and crew.

The Colon Muggers must be the world’s best and if you haven’t been mugged by one of them, you haven’t been mugged. Colon is in one of the few countries that runs schools for these gentlemen, with courses in drug trafficking, kidnapping, and plain everyday murder. After successfully completing their training, many graduates are exported to less well-endowed regions, such is the demand for their talents. I made their acquaintance soon after my arrival. Communication between them and the chaps in Grenada must have broken down or they would have been informed that I had already been nobbled and there was little left.

My partner in this drama, Terrell Adkisson, was not exactly my idea of a Texan, as I had been brought up watching John Wayne and Gary Cooper knock ten kinds of rice pudding out of the Indians. Needing fuel for my trip through the Canal, I was hitting the trail along the Old Pontoon when I heard a slow, drawn-out, ‘Hooooowdy.’ I spun round, dropping my hand to my hip, then quickly removed it in case I conveyed the wrong impression. I was confronted by a scruffy individual wearing checked shirt, glasses and a pair of ex-army trousers four sizes too big. At first the stubble on his face and grey crew-cut hair suggested he was older than I. In fact he was younger, proving again that ageing is a deception practised on people after a long sea voyage and nights without sleep.

Terrell owned Altair, a new 28ft glassfibre Bermudan sloop, and had recently given up teaching mathematics in Texas to sail around the world with his 22-year-old nephew, Leo, a blond young man who had previously spent his spare time playing guitar in a pop group. Terrell needed petrol, or gas as he put it, so we started out on the first of our many adventures together to a garage only a mile away in the Colon district. I had enough money to buy 5 gallons of diesel; Terrell had his wallet in his back pocket. The garage attendant warned us to be careful, his darting, frightened eyes telling their own story.

Groups of men were watching us but it was ten o’clock in the morning, broad daylight, so why worry? Halfway back to the yacht club I turned to speak to Terrell and spotted three of the biggest men I’ve ever seen coming up behind us, with knives. I had dreamed of moments like this. I would push the women and children to one side, take a flying leap, legs drawn to manly chest to shoot out like two murderous pistons, taking the two nearest villains in the throat, killing them instantly. The third would be despatched with a karate chop to the head.

What I actually did was to shout a warning to Terrell and run in front of a line of oncoming traffic. A screeching of brakes... I bounced off a car, the fuel can turning into a tiger that wanted to go walkies. It bolted across the intersection, dragging me with it, to get clobbered by a truck coming the other way. When I staggered to my feet, Terrell had a man on each arm, with knives at his chest, while a third tore at Terrell’s wallet.

I shouted as loudly as I could to let the men know I really meant it, ‘Hang on, I’m coming.’

There was a sound of ripping and Terrell stood in the main street minus trousers – and wallet. He started running after them, with me trying to stop him. If he caught up with them, they would surely kill him but, outdistanced, he abandoned the chase.

Terrell had lost a few travellers’ cheques, no cash. Soon his sense of humour returned. ‘Just my luck to be arrested for indecent exposure,’ he said, looking down at his fancy underpants. He was attacked a second time in Panama City, but this time Leo came up behind with a tin of peaches and started hammering the would-be mugger, who ran off. In Colon that could be described as a bad day at the office. It is inadvisable to linger long in Panama.

The 40-mile canal trip is straightforward enough, through pleasant lakes and waterways, with three locks at each end. You require a ship’s pilot (normally an ex-Merchant Navy captain), four line handlers and four 100ft lengths of rope. The handlers adjust your lines to keep your craft in the centre of the dock as you rise and fall, for which you supply the food and grog for the day and their rail fare back. In 1976 that was just $1. Line handlers are not hard to come by. They reckon it’s a nice day out.

I arrived at the Balboa Yacht Club on the Pacific side with precisely $3 so I sold my outboard for $200 to put me back in funds. Again I bought the cheapest food available: unmarked tins of corned beef that turned out to be mostly jelly, tins of tuna that looked and tasted like grey sand, a sack of rice alive with weevils, flour, baking powder and a large tin of treacle as a treat.

For my Pacific crossing (8,000 miles or so) I bought two charts. My first landfall would be Hiva Oa in the Marquesas Islands, a voyage of 3,500 miles or so. Navigation to date had been by dead reckoning with noon sights for latitude and radio direction finding; now I would be sailing into areas of reefs, few lighthouses and fewer navigation aids. Accurate navigation would be essential so I would have to learn how to take sights for longitude. I managed to buy a 1976 Admiralty Almanac and a second-hand set of reduction tables, and for accurate timekeeping (one minute in error can put you 15 miles out of position) I helped antifoul another boat whose owner gave me a small portable receiver in payment. This one had short wave, enabling me to pick up the American station WWV which broadcasts time checks 24 hours a day. There was one small problem: the mirrors on my sextant had lost their silvering. A lady presented me with the mirror from her handbag. Cut to size, it made my sextant serviceable again. I made one major mistake when, trying to save money, I bought a gallon of cheap antifouling. As things worked out it would have been less expensive to have paid more for a better quality.

My custom ashore was to sit on the edge of a group of cruising people, listening to their tales of the sea, trying to pick up tips. Solitaire, the only craft I knew anything about, had now carried me 7,000 miles or more, but I still had not picked up much sailing terminology: talk of schooners, ketches or heavy weather sailing and I was lost. I tried to fade into the background with the odd ‘Hear, hear’ and ‘Dashed good show’, trying to pretend I was one of them.

On one such occasion I was with a crowd at the Balboa Yacht Club discussing the particularly bad weather at that time of year in the Caribbean. One American had lost his trimaran. He and his crew, over-tired on the trip from Grenada, had tried to come through the breakwater at night, missed the lights and hit it, but managed to get off before it sank. A Canadian family had tried for ten days to sail in the other direction but after a fierce battle had given up and retraced their steps through the Canal. Another five boats were hoping for an easterly passage, meanwhile waiting for the seas to die down. A Frenchman had ripped the floor out of his yacht to cover the cockpit and give protection from breaking waves. I thoroughly enjoyed their talk: you could virtually taste the salt on your lips.

‘Leslie, you’ve come through the Caribbean from Grenada single-handed,’ someone commented.

‘Er, yes.’ A mass of weather-beaten faces turn towards me.

‘How bad was it in your opinion?’

‘Pretty bad,’ I replied.

‘Yes, but how bad?’ the voice insisted.

I didn’t want to tell them I spent my time below, reading, while Solitaire and the self-steering did the work. I couldn’t talk about wind speed as I had no wind indicator and I would not know a 20ft breaking wave from a 10ft, yet I desperately wanted to be accepted by these adventurers. I came out with the incident that made me put in my hatchboards. ‘Well, my carpets got wet.’

There was a deathly silence.

I escaped next morning to the island of Taboga, 6 miles away in the Pacific. Terrell and I had heard of a wartime landing barge on the beach there, against which it was possible to tie alongside, wait for the tide to ebb and then antifoul the hull. Altair was done on one day, and Solitaire the next. Not too keen on the idea, my boat started acting like a spoilt child on bath night until I tied her up, when she settled. I made a better job of the wound in her side and then applied my cheap antifouling which went on like weak whitewash. Solitaire deserved better, but with only $60 left in the kitty I had little choice. At least we would be sharing discomforts, I thought, remembering my jellied corned beef and gritty tuna!

Terrell and Leo sailed a week ahead of us, as there were a few jobs still to do on Solitaire. I was sorry to see them go, but we would catch up later. I felt like I was living in Germany, when a knock on the door could mean a call from your local friendly Gestapo, inviting you to sample the delights of a lovely prison camp. Only now, in Taboga, it would be the army or police searching your yacht for drugs.

They paid a visit the day before I left, bringing a dinghy I was supposed to have left on the beach, one I knew belonged to a nearby yacht whose mast had been broken coming through the Panama. A young man with a large Dalmatian dog was looking after the parent boat while its owner was away. As I towed the dinghy over to tie it on the yacht’s stern, I could see the dog running on the beach. Later I heard the full story. The young man had taken it ashore for a walk, the army had tried to shoot it and the boy had put his arms round it for protection. He was now in hospital, half his hand blown away.

I sailed for Hiva Oa on Thursday, February 26th, 1976, and for two days Solitaire made good time in light winds, gliding along effortlessly on her clean bottom. Conscious of my earlier mistakes I spent hours in Solitaire’s cockpit, listening to WWV for time checks while I took sights for longitude which, in the early days of the voyage, I could easily confirm. As the days passed I began to feel more at home at sea than on land. Solitaire’s constant movement and my spartan diet kept me slim and fit. As I am blessed with ginger hair and freckles, the sun enjoyed itself colouring my skin anything from brilliant red to deep purple. It was a surprise to find it browning me as well.

No webbed feet or gills yet, but I was metamorphosing into marine life. For instance, storms and calms are treated differently by sea animals. To land life, a storm is a personal attack, knocking down a man’s chimneys, flattening his crops, whereas calms go unnoticed. Sea life, however, accepts storms that may sink ships but are not malicious, and realises that the patient ocean recognises no flags, is not vindictive and, far from finding pleasure in rolling you over, does not even notice you. But a calm is a personal attack and in early days could mean back-breaking weeks in a longboat, towing a square-rigger while searching for life-giving winds, half the crew dying of thirst or hunger.

Solitaire hit her first long calm east of the Galapagos Islands. After the early days at sea progress had slowed with runs of only 30 or 40 miles a day, periods without wind, the self-steering on a knife edge. Now she was about to spend four days in an ocean of thick blue oil below a sky whose solitary, unmoving cloud would retain its shape and position hour after hour, leering down on our discomfort. We carried no burgee at the mast top to indicate wind direction but on our backstays bore long, red tell-tales which became skirts covering the most beautiful legs in the world, legs that made Betty Grable’s look like matchsticks. They would lift slightly, showing trim ankles and then, seeing they had my interest, drop teasingly.

Just over the horizon was a Giant bathing in this lake of oil, his movements causing a long swell that swayed Solitaire monotonously from side to side. I grew to hate him and the Leering Cloud and the Teasing Skirt. The slapping sails, the rattle of the rigging, the strange sounds that would take hours to find... a shifting mug, a loose can. One sound had lasted longer than all the rest, a bruuuph, bruuuph, over and over again. Whenever I moved from my bunk I would alter Solitaire’s balance and the noise, hearing me, would stop. Even if I slid along the floor on my belly, holding my breath, I could not catch it. Then the Giant scrubbed his back, and I had it. Bruuuph, bruuuph. A new drill was rolling back and forth in a drawer. I watched it with pleasure for a few minutes, like a cat with a mouse, then I pounced. Clutching it in my fist I took it to Solitaire’s stern, and threw a brand new drill worth a bag of rice 50 yards into the sea. You really should not do that sort of thing. Later I learned the secret of destroying calms. You simply ignore them.

Once the sea was flat I would drop the headsail, and put a reef in the main to reduce chafe, which drives the chappie taking the bath bananas. Invariably I would spend my first day on deck busy with odd jobs, always remembering to smile and whistle from time to time for Leering Clouds hate happy whistling. To attract the Teasing Skirt I would bring out my secret weapon, a couple of good books, and while reading would watch her advances from beneath lowered lids. Red skirts hate being treated in this way and soon show all they have. There are compensations to long calms for at the end you will hear the Hallelujah chorus played by the London Symphony Orchestra. It’s like sitting in the Royal Albert Hall, eyes closed, waiting, waiting, waiting. Then a faint cough; a ripple touches Solitaire’s side. A flute softly tunes up and the sails stop flapping. The string section plays a few bars and her rigging hums. The conductor taps his baton, a slight pause and Solitaire is sailing and the most marvellous music in the world is heard. The chorus sings Hallelujah, Hallelujah, higher and higher, Haaaaaleeeelujah...

Solitaire sailed 200 miles to the east of the Galapagos Islands, passing through areas showing six per cent calms on the charts. She had to overcome a north-flowing current of 15 to 20 miles a day as she struggled over the Equator for her third crossing to the free-flowing trade winds that started 300 miles to the south. She was sick as she told me but again, because of my inexperience, I took no notice. She lost her will to live, dragging through the sea on legs too tired to move. I assumed the slow progress to be due to the adverse current and light winds, and fought back with every sail arrangement I could possibly manage to contrive.

The first light breezes from the east indicated the start of the trades. Solitaire carried no whisker poles for holding out twin headsails simply because I could not afford them. Instead I had made do with two 13ft aluminium poles to which I had fitted eyes at both ends. I tried using these with both the number one and two genoas hanked on, plus the full main. Still she would not budge. Seas flowed past her and the self-steering lost control, even the tiller having little effect upon her erratic course. She would broach continually, swinging 180° and backing her sails.

When finally we came into the true trades, constant Force 3 to 4 (7 to 16mph), I sailed on a broad reach, with a quartering wind, the number two genoa poled out, a reef in the main. Yachtsmen would have considered me crazy to have so little sail, and in such conditions I would have loved to have set a spinnaker, had I possessed one. Half of the course settings were by sail adjustment as the self-steering was of little practical use.

Unknown to me a cancerous growth was spreading its tentacles around her. Solitaire’s cries for help quietened as it entered her mouth, silencing her. Now she was wallowing, hardly noticing the winds that entreated her to frolic.

Wednesday, March 24th, found us at latitude 6°05´S. We had left the Equator 365 miles astern and were 300 miles below the Galapagos Islands. A favourable current gave us an extra 10 to 15 miles a day in south-east winds around Force 4. In these ideal conditions Solitaire should have been romping along, covering at least 120 to 140 miles a day. All she produced was a limping 50 miles. Our trailing log clocked only 1,115 miles in 27 days, not a third of the way to Hiva Oa, with half our food and water already consumed.

On the self-steering rudder and under the stern I found pink stalks up to an inch-and-a-half in length with a white and grey bud on each top which I cleaned off with a paint scraper. Could these growths be the reason for Solitaire’s illness? I rejected the idea when I remembered antifouling her hull only five weeks earlier. Surely that could not be the cause.

During one of those cleaning sessions I found myself in one of those stupid situations that happen only to single-handers. I had pushed myself through the bars of the pushpit as far as I could, leaning well out and holding on with one hand while scraping with the other. I felt a pull on my hair and threw the scraper into the cockpit, grabbing at my head. My hair had become tangled in the trailing log line! It took me a good half hour to free myself. After that I had a dread of getting stuck up the mast, only to be discovered a year later as a swaying skeleton.

Afloat it is difficult to see all of Solitaire’s hull as it rounds sharply just below the waterline and falls away to the keel, so I decided to lean out as far as possible, using a lifeline and an extra rope for support. I had expected to find someone’s old sail or a bunch of rope tangled on the keel. Instead I found a swaying pink and white garden completely covering the hull, keel and skeg. No wonder Solitaire had wept. Again I felt as I had when the bruuuph, bruuuph drill had come to light. I prepared to pounce then, deflated, realised it had us in thrall, that I had a plague of goose barnacles.

There were three reasons why getting rid of them would cause problems: I’m a poor swimmer, there were sharks in the area, and I’m a confirmed coward. I spent the morning making every conceivable excuse I could think of for not going over the side. Solitaire listened in silence except for a muttered slop slop, slurp slurp. I suppose she could have nagged that I had been the one to give her a cheap coat of antifouling and was thus responsible for her sickness but she didn’t, which made the need to be forgiven the more dramatic. I badly needed to hear her whisper and laugh with me again.

In the afternoon I dropped her headsail and under the main brought her onto a reach, allowing her to roll in 3–4ft waves. The rubber dinghy was inflated and secured to leeward. With two lifelines and armed with a scraper, I dropped into it and then, holding onto the toe rail, reached down the hull as far as I could on each roll. I spent an hour or so on one side, clearing only a foot and a half of the barnacles, their rubbery feet still clinging below the waterline.

Hanging onto Solitaire, trying to keep a grip with my toes as the dinghy dropped away, made me want to give up and throw up. Oh well, tomorrow it would only be worse so I climbed back on board, turned Solitaire around and worked on her other side. Then we were back on course, broad-reaching, with our number two genoa filling with only a slight improvement in her performance. All the thanks I got for my trouble was slop slop, slurp slurp.

For the next few days I lost interest in everything but trying to ease the pain in my arms and stomach. We became a couple of tetchy invalids reluctantly settling for a desperately slow passage. To save water I stopped shaving and started my first intentional beard as we slurped across the Pacific in perfect slurping conditions. I would spend hours in the cockpit marvelling at this sailing paradise with cool trade winds and clear, blue skies broken only by a few wispy clouds. The transparent waters provided a private aquarium of beautiful tropical fish that would look up, saucer-eyed, to admire our exotic garden of pink stems and nodding white heads which grew larger with each slurping mile.

At night I had an I-hate-barnacles hour. No longer content with merely scraping them off I wanted to inflict pain and hear their screams, to collect every last one and lay them on Solitaire’s decks so that we could both witness their death throes. The day of reckoning was drawing near.

On Friday, April 23rd, after eight weeks or so at sea covering 3,020 miles and with 600 miles still to go to Hiva Oa, we sighted our first ship. To be honest, it was not a ship but a yacht and they sighted us, not I them. I had felt like a spot of work that morning and spent half an hour picking the weevils out of my daily cup of rice. Despite this strenuous exercise I still felt pretty active, but could think of nothing that demanded attention until I remembered my golf clubs, which were as dirty as old boots. So I spent the morning below cleaning them.

Towards noon I heard the sound of a trumpet. If that’s Gabriel, I thought, I’m not going, and banged my head to clear it. Then it sounded again. On deck, clutching my five iron, I saw a 40ft boat off our bow manned by an elderly couple and two in their mid-twenties. Canadians by the home port on their stern. Their twin-poled headsails had been eased and they were holding position a few yards off. I walked up to Solitaire’s pulpit.

‘Ahoy,’ they shouted. ‘We’ve had you in sight all morning. Seeing no one on deck we became worried.’

‘I’m fine,’ I said, waving my iron. ‘I was cleaning my golf clubs.’

There was a thoughtful silence. ‘Do you know if there’s a bank in Hiva Oa?’ they asked. ‘We need to cash a cheque.’

‘I’m sorry,’ I replied. ‘I’m a stranger here myself, don’t often play this course.’

Another long silence. ‘You sure you’re all right?’

‘Perfectly,’ I assured them.

With that, they pulled in their sails and drew away. I couldn’t believe it. After eight weeks with no one to talk to, they were leaving without even an invitation to coffee. I wanted to say something really mean but the best parting shot I could think of was, ‘You haven’t seen my bloody golf ball, have you?’ The I-hate-barnacles hour that night was extended by 30 minutes.

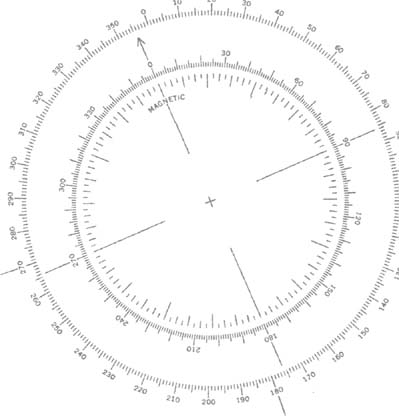

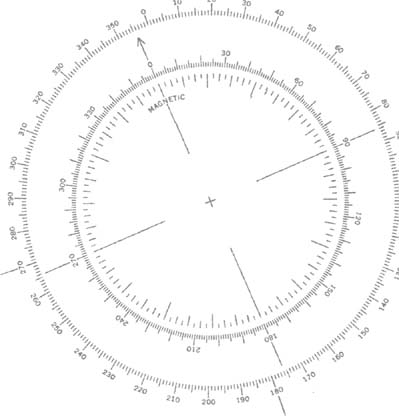

On Monday, May 3rd, the noon sight put us 47 miles from Hiva Oa. Looking back over my life I seemed to have done few things right so now I wanted desperately to recompense by making a good landfall. I had nothing to confirm my longitude calculations, apart from some days when I had taken two sights, morning and afternoon, which gave position lines crossing at about our latitude.

Slow progress, a flat sea and clear skies helped my navigation. Today I checked and re-checked a dozen times, for failure to sight land next morning would mean I had let down Solitaire yet again. In the afternoon I decided to test the engine, which normally I ran every two or three weeks, just to circulate the oil and top up the battery. I turned the key but nothing happened so I went over all the connections. Those on the solenoid seemed loose and dirty. Cleaned and tightened, we had a motor again!

The Marquesas Islands stretch for about 200 miles, half a dozen of them 3,000ft high or more, and on a clear day they should be visible for 30 or 40 miles. Hiva Oa, at 3,520ft, should not be difficult to spot, despite having no lighthouse or radio direction beacon. But, with one error of more than a thousand miles to look back on, anything was possible!

As night fell the sky filled with stars, although a sea mist obscured the horizon. Solitaire should have been within a few miles of the island but I could see nothing, no lights, no black shape. The sea was empty. I dropped all sails and waited for dawn. As the sky grew lighter, there was still no land. The sun had not appeared but it was daylight. Now I would settle for anything, a smudge in the distance, even land birds. All one could see was sea. I could not face another Brixham, another Brazil, another broken marriage. I went below, recorded another failure, and made myself a cup of tea. All I could do now was to take fresh sights and try to discover my mistake. Defeated, I climbed back into the cockpit.

I heard the Hallelujah chorus so loud it almost took my head off and tears of joy ran down my face. She had been there all the time, hiding beneath the early morning mist, the most beautiful island in the world. Her purple and blue mountains reached up for the sky, green palms swaying in the breeze, surf breaking on golden sands. After 68 days at sea, Solitaire and I had made it and had got something right. I savoured every precious second.

Terrell had lent me one of his charts, from which I had sketched the island. The anchorage was at the far end of a bay and we spent the morning motoring there, Solitaire still rolling drunkenly with her cargo of barnacles. That morning I hated nothing, not even the blasted barnacles.

The bay we wanted turned back on itself. There was a moment of doubt when I could not see it, then I spotted a beach, palm trees, a few homes up in the hills and two boats at anchor. Solitaire turned to meet new friends, a blue ketch flying a French flag, an American flag on a trimaran with people on its spacious decks.

I dropped anchor and started to put Solitaire in order, making a final entry in the ship’s log: ‘23.15 hours GMT. Anchored Hiva Oa, distance by trailing log 3,655 miles after 68 days at sea. On board one gallon of water, two pounds of rice, two tins of corned beef, six Oxo cubes.’

A dinghy left the ketch and started across. The men and women aboard could speak good English with a heavy French accent. Did I need anything?

Where could I buy bread? There was a store in the village, an hour’s walk away. They left but the man was soon back with half a loaf, a jar of marmalade and a can of beer.

Later another dinghy came over from the trimaran with an Englishman in his early thirties and a beautiful doll-like creature whose golden skin and almond eyes showed traces of the Orient. Jeff and Judy were the couple I would spend most time with in the Marquesas. There are few men I have grown to admire more than Jeff. Born in Britain, he became a veterinary surgeon and moved to the west coast of America where he built his trimaran, Dinks Song, to escape the more mercenary practices of his profession. Each day shared with him brought fresh surprises. It started with his playing the guitar, singing in a voice that would have earned him a living anywhere in the world. He went through numerous instruments which finished one spell-binding night when he stood on his foredeck at anchor in the bay at Fatu Hiva, playing the hauntingly lonely music of Scotland on his bagpipes – unforgettable!

I learned more and more about this man, mostly from Judy. He held an aircraft pilot’s licence. With his high-powered rubber dinghy he water-skied and taught the Polynesian locals to emulate him. But what I remember Jeff for most was the 3-mile walk to the village, his face covered with dust, sweat and pain, never complaining. Jeff had only one leg. He had lost the other as a small boy in a coach crash in Scotland. People like Jeff make you humble – even after your first true landfall.

Now that Solitaire was about to be cured of her barnacle sickness, I found that I had contracted a terrible disease, the worse because you inflicted it on your friends. It is a disease of brain and mouth and is particularly prevalent among single-handers. It normally lasts for a few days after any long voyage and is called verbal diarrhoea. The brain keeps sending messages, ‘For God’s sake shut up, you are boring the pants off everyone’, which the mouth refuses to receive and continues to spew out garbage. On that first night in Hiva Oa Jeff and Judy made the mistake of inviting me back to Dinks Song for dinner. Judy, a first class cook, had spent most of that day baking. I completely demolished her work and was finally got rid of in the early hours, being bundled into their dinghy with a mouthful of cake, still trying to talk.

I awoke next morning from a deep sleep to a glorious day. A warm breeze rippled the still lagoon, palm trees barely a-sway while Solitaire slept on. I tried not to disturb her as I moved forward to check the anchor but managed to shake her slightly, whereupon she yawned and stretched. Her chain lay limply on its sandy resting place 3 fathoms below, looking as if it could be touched from the boat. I walked softly back. ‘Sleep on, love, you’ve earned a holiday.’ With a contented sigh she snuggled back into her clean, warm bed.

There was no movement from the other boats; perhaps Jeff was watching from behind portholes, frightened lest I return for more cake and conversation. Then I heard a faint chugging and round the headland came the bow of a boat, standing on which was an attractive woman, complete with movie camera. Her long, blonde hair streamed down her back, caught by the breeze but held partly in place by a fawn-coloured topee of Indian vintage. The bow belonged to a lifeboat with an ultra-short mast. At the tiller, like an old-time film producer complete with thick black glasses and also hiding under a fawn topee, was a man. Ye gods, I thought, it’s Bogie and the African Queen. They circled around the lagoon a couple of times, still filming. I dashed to comb my hair and emerged in time to see them anchor, whereupon I rowed across.

Juli and Dontcho were Bulgarians permitted by their government to carry out an experiment in the Kon-Tiki vein. They had left the coast of South America intending to sail to Fiji, proving that you could survive long periods at sea by dragging a fine mesh net behind and collecting plankton, the small organisms that are found in the oceans. Soon after leaving they had lost their mast and were making do with a jury-rig. Dontcho was a scientist with black hair to complement horn-rimmed glasses. Shorter than myself, he was a bit overweight so the plankton must be doing their stuff, I thought. He could speak little English and relied on his lovely wife, Juli, a concert pianist, to translate. Slim and tall, she could well have been in films, her skin darkened by the sun to contrast strikingly with her blonde hair.

Their lifeboat was madness. The Bulgarian government had insisted that they carry a powerful transmitter and had supplied a 24 volt set, knowing the boat had only a 12 volt supply so that it could never be used. Heavy gauge stainless steel bottle screws and shackles that made my mouth water were used to put tension on thin ropes. The fibreglass water tank had been built with the wrong resin, souring their water. Their method of navigation included timing sunset to obtain longitude. They had been trying to correct their watches with BBC time checks, ignorant of the constant time signals from the American station WWV. Although they had three portable receivers on board only one worked, and that poorly.

After all my own blunders, and remembering the help I had so freely received, it was satisfying to contribute in return. We soon had all three sets blasting out WWV signals, and the water tank cleaned. Doncho and Juli made a great deal of any kindness shown them, a truly brave and lovely couple of whom I became very fond.

Solitaire and I will always look back on the Marquesas as a Shangri-la, an earthly paradise. On the morning after our arrival I walked to the nearby ramshackle village situated on a hillside. Looking down on the lagoon I could see Solitaire still slumbering in clear waters. I cleared the French Customs and then tried the village store. Some of the things on display, eggs and tomatoes for instance, I was not allowed to buy. Items in short supply were kept for the villagers but there was no shortage of mouth-watering delicacies.

Stalks of bananas, coconuts and bread fruit, which makes the world’s best chips, were plentiful as was that goddess of fruits, pamplemousse, a grapefruit as large as a football, sweet and streaming with juice. Eaten for breakfast with a cup of coffee, you were set for the day. I bought some of the cheaper food including flour, rice and baking powder.

Everyone was going back that night to dine and watch some native dancing. Tickets were $3 each so I decided to give it a miss. I had less than $60 left and there seemed little chance of my finding work until reaching New Zealand or Australia, more than 5,000 miles away.

On the way back to Solitaire I spotted the Canadian boat we had met in the Pacific and went over, minus golf clubs, to inquire if they had managed to cash their cheque. They apologised for not stopping with me longer and made up for it by inviting me to dinner the next day.

At six that evening I sat on Solitaire’s deck drinking a coffee and watching the other yachts and their crews preparing for the native dancing. As the dinghies moved ashore, Jeff and Judy came over to Solitaire. The crowd had realised, by the food I had bought, that I was short of money and had clubbed together to buy me a ticket, deciding not to collect me until the last minute so that I could not refuse. I tried always to repay this sort of kindness, but it seemed that I always ended up at the wrong end of the stick.

An American yacht with five young men on board came into the lagoon with alternator-charging problems. A broken holding bracket was the only trouble so I fitted one of my spares for them. During our conversation it was mentioned they had a taste for English gin and as I still had two bottles on board left over from my Brazilian beach party I wanted to make a present of them, but this they refused, insisting on paying the full local price. The battle went on for a week, with me holding the ace and the only two bottles on the island. I would go over with my gin and describe the pleasure of rolling this nectar around the mouth, of feeling it trickle down a parched throat, watching them grow more desperate. It seemed like stalemate. On the morning they left, I waited until they had their anchor up, rowed over and placed the bottles on their deck as they slipped by with cries of ‘Up the British!’

An hour later they were back again with engine trouble so I went over to lend a hand. The battle of the gin bottles was not mentioned. Good, I thought, they’ve accepted their defeat with grace. At dawn the next day I was rudely awakened as they sailed past Solitaire to raucous Yankee battle cries. I waved them good luck, then breakfasted on pamplemousse and the $20 bill they had stuck in my coffee jar. One of them must have swum over while we were messing with the motor. There was a note: ‘No Englishman’s going to get the better of a Yank.’

One of the people never to visit Solitaire was the filthiest old man I have ever met. The store had run out of bread one day and I was directed to an overgrown path on the village edge down which, they told me, was a bakery. I pushed through the creaking door of a ramshackle shed into a black interior, adjusting from the tropical colours to dusty gloom within. I felt rather than saw the diminutive Chinese man, who shuffled forward smiling, saying the only words I ever heard him speak, ‘Me British.’ He reached in a pocket and brought out a tattered British passport. Reluctantly I bought one of his hot rolls and, halfway down the path, hungrily broke off a piece. My taste buds turned my feet in their tracks to buy another.

Each day thenceforward I bought two of his rolls and each day he would show me his passport and say, ‘Me British.’ I wished I had an old medal to give him – if not for his bread, then for being a true patriot.

Solitaire and I loved our easy life. A freshwater stream ran into the lagoon, diluting its sea-salt concentration. The goose barnacles nodded their heads worriedly, turned black and died. I had relished much contentment, particularly during my second marriage, but if you had asked me whom I disliked or envied I could have named none. It was a feeling destined to last until I returned home nearly two years later. Him I would normally have disliked I now only pitied, the wealthy in their homes or yachts I no longer envied, but once evening fell I uneasily needed to return to my boat. Money, of course, would have helped me to do more for Solitaire, buy the best antifouling, more sails, charts, pilot books, but I had chosen this life and regular wages would have meant regular commitments. I expected to pay my way, but I wanted to choose the method. My pleasures were cheap: I had never smoked, and drinking was for special occasions. My clothes would consist of shorts and an open-necked shirt, my feet bare.

I felt affection for the people I was meeting; they did not consider the world owed them a living. I would visit their yachts and, if the owner happened to be working, would simply join in. I had boxes of spares left over which always came in useful. My rubber dinghy allowed me to ferry large loads ashore and my 5-gallon containers proved useful for getting water to the other yachts.

Since there was only food to buy, money had little meaning for the natives. Solitaire inevitably had more fruit on board than I could ever eat, picked by myself or traded for things I no longer required. Locals would place stands of bananas and the odd fish on deck. It was normal practice to row across to new arrivals and discover what help they required.

The cruising world is both large – meeting people from many countries – and small, particularly when greeting new arrivals and receiving news of old friends. People are like mirrors and reflect what they see: if you are genuinely pleased to meet someone and bubble inside, that feeling will be returned. But if you did not fit in and took advantage of friendships, you would be slowly ignored, wither and fade away.

When subsequently I looked back on the time I spent in the Marquesas Islands I remembered half a dozen eggs. Juli and Dontcho were among my first friends to leave and on their last morning in Hiva Oa I wanted them to breakfast with me, the first time Solitaire had guests for a meal. I spent a good deal of time deciding on the menu including pamplemousse for starters, of course. Tinned butter could be obtained in the village, a bit expensive, but a special treat, which would go down well on the crusty rolls from my Chinese countryman. I would buy a couple of eggs each for the three of us, and finish with the marmalade given me by the French couple. All went well until I discovered there was a shortage of eggs on the island. After trying the village store, I chased every cockcrow in the hills. All the other yachts were reduced to powdered eggs and that night I went to sleep knowing that I would have to accept second-best. It was quite late when two strangers in a dinghy woke me: they had just arrived in the lagoon and, having been told by the people on the other yachts of my quest for eggs, they had taken the trouble to bring them over. I think that’s what cruising is all about.

It was time to waken Solitaire from her slumber. Fatu Hiva, where many of our friends were, would be our next stop, with no navigation problems this time. Although the island was 50 miles away, on a clear day you could see her majestic peaks reaching into the clouds so I decided to sail through the night and arrive at dawn. There were a dozen yachts at anchor when we hove to but not a soul to be seen on the boats or beach. The anchorage is small compared with the size of the bay, which must be one of the most impressive in the world. A shelf extends off the beach for a few hundred feet, then quickly drops away to 15 fathoms. Winds are invariably offshore and now and again blast down between the mountains at 60 miles an hour. For all that, it is a safe and beautiful harbour, once berthed.

Solitaire circled the other craft feeling like a child that had not been invited to her best friend’s birthday party. Meanwhile I was blowing on a whistle and shouting. Jeff’s trimaran was there; it crossed my mind that he had warned the others of my verbal diarrhoea and I imagined them hiding in their cabins, the locals concealing themselves behind trees, in case this new horror spread to their village. Solitaire nudged her way between Dinks Song and another yacht as I peered through portholes, expecting beady little eyes to peep back.

When the echo sounder showed less than 20ft, I let go the anchor. Solitaire moved slowly astern sulking, as if to say, ‘I know when I’m not wanted.’ Everything was as dead as a dodo. Had we dragged our anchor, no harm would have been done, as only open waters lay behind us. If Solitaire felt she had been cast aside and snuck away in the night, the worst that could happen would be bringing a reluctant child back against wind and tide.

After a cup of tea I put down my head and slept. Jeff woke me the following morning to tell me that one of the village lassies had been married. The yachties had joined in happily, the ladies helping to prepare the bride. Solitaire and I fell easily into the life of receiving guests and visiting other craft although most of my time was spent with Jeff and Judy. As there seemed to be a shortage of girls on the island, Jeff arranged to take a dozen of the village boys to another island, which had a similar problem – in reverse. The islands spoke French, which both Jeff and Judy could understand so there would always be a few Polynesian men on Dinks Song.

Through whom I was introduced to two new forms of food. When approaching the island, I had seen palm trees perched on the sides of the hills sheltering sloping tables. These were used for drying bananas, which retained their flavour but became quite chewy. I later found them in Tahiti, where they were far more expensive. The second food was a piece of a giant ray that came into the lagoon. Apart from a seat in the front row, we had a running commentary from the boys. With a half dozen lads on the paddles, the chief went out in one of the native canoes, by tradition the only person allowed to harpoon it. We watched him jump from the bow of the boat onto the ray’s back, putting the full weight of his body behind a thrust. Then he virtually flew from the water as if dropped into a cauldron of boiling oil. I asked one of the young gentlemen how often the village acquired a new chief.

When the poor ray was dragged ashore it looked more like whale worked on by persistent steamroller. The natives started to hack with meat cleavers and the shoreline reddened with its blood, the sea taking on the appearance of a washing machine that had gone berserk as the sharks came in to feed. The yachties, who for days had swum over to Solitaire, started using dinghies, but memories were short-lived and soon Jeff was giving his water skiing lessons again. When he and Judy left with their cargo of amorous young men, it was to be for only a few days. In fact, it was the last time I saw them.