Lymington

1980

The first circumnavigation, leaving Lymington on Monday, August 18th, 1975, and arriving back on Sunday, April 30th, 1978, had taken 12 days under two years and eight months. The east to west voyage had been made far too quickly and I had missed out many of the countries I would have liked to visit. Such an exploration, of self as well as the world, should take a minimum of ten years and anything up to a lifetime. Now my main driving force was to make a fresh start to round Cape Horn.

The distance Solitaire covered on that first voyage was roughly 34,000 miles, with a best day’s run of around 149 miles. The longest time spent alone at sea was 69 days, with a best non-stop distance of about 6,000 miles. Not that any of this was important. Solitaire and I were neither equipped for nor desired to set records. It’s what is in your head and heart that’s important, not what Joe Soap, who has never stepped on a boat, thinks. Was it a good sail, a warm day, did the sun set in a blaze of colour, did the dolphins visit, were we contented? Those are the questions whose answers matter.

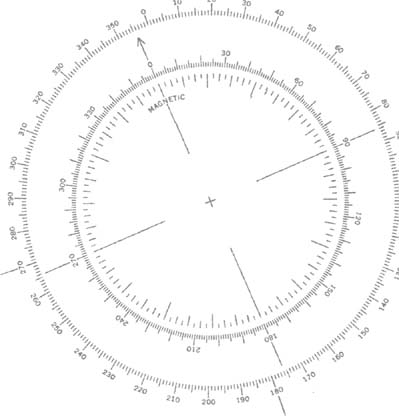

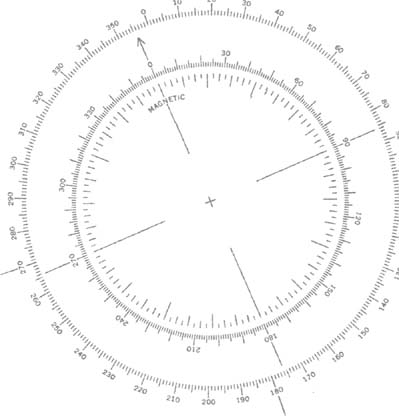

I shall never forget or forgive my first navigation blunders. After the Brazilian disaster I made yet more mistakes but thenceforward I kept a mental note of Solitaire’s position, the weather conditions she was in and the dangers she might face. When laying out a course, I would draw lines from point to point, trying to skirt around areas of calms, storms and shelving seabeds, using such charts as I possessed. Sometimes things go wrong and three or four problems are thrown at you together. Then there is no time to think and you must react instinctively, preferably having the cure ready before you catch the disease.

For me the time taken on a voyage was important only as far as food, water and the boat’s condition were concerned. If I could make 100 miles a day, I would be content. Had I the funds I would have worked out the stores required, then doubled them, but I was in no position to do this until towards the end of the voyage. The second circumnavigation, this time west to east, broadly speaking depended on three things.

First, my family’s reaction. Both parents were now in their 70s. My mother had been in poor health for some time and brother Royston had spent much of his time caring for her and Father while I was gallivanting. If Roy wanted to alter his way of life or the voyage distressed my parents, then it would have to be delayed.

Second, my friends had an influence. Hitherto they had only encouraged me but if they tried to dissuade me I would sail for Cape Horn no matter, although I would be apprehensive, and really alone for the first time on any voyage.

Third, finance. I had to find work quickly. I left England in 1975 with £300 and returned with the same sum, which I had saved in Australia. But to carry out modifications, equip Solitaire with new gear and stores would cost at least £2,000. My best way to make this money (and quickly) would be to try for an overseas contract in electronics.

I spent my first night in England with Group Captain Rex Wardman and his wife, Edith, who welcomed me warmly with a hot bath, sizzling steak and a bed, full of sleep. Later that week Rex drove me home to Birmingham, where the news was good.

If my family, who had moved into a small, semi-detached house, did not exactly encourage, they certainly made no attempt to discourage me, their attitude being that the sea was my life and I would be off again. On my arrival I found a couple of reporters. In writing to my family I had omitted or glossed over the bad times but when talking to the press, I forgot this and mentioned some of the sailing’s gorier aspects, which caused the newspapermen and my family to blanch. My photograph duly appeared in the papers, not that that means anything, but parents like this sort of thing, provided it’s not just before they hang you!

Three days later Rex drove me back to Lymington, whereafter I spent a week with Rome and his mother, catching up on my writing. I contacted Saab who told me to take my engine to Savage Engineering in Southampton, where the motor was stripped, cleaned and serviced and the fuel pump attended to for an all-in charge of £20! After that I had no further trouble, making up for all the problems I had experienced after leaving Australia.

Most of the remainder of my time was spent talking to Rome about the modifications I wanted. The major task was to change Solitaire from sloop to cutter rig and perhaps add a bowsprit, which would put her headsails further forward and thus prevent her broaching when on a run. Cutter rig would also give me a bigger choice of sails. When beating into storms I could get a better slot effect with the main by using a small staysail, which would also serve as a backup for self-steering. The one objection against the mod was that I might have to fit running backstays which did not appeal. When Rome sailed his transatlantic race, he fitted an unsupported inner forestay on his boat but agreed it was not worth the risk in the Southern Ocean. Having experienced the Roaring Forties on Adventure in the Whitbread race, he told me about the conditions, explaining the problems in his quiet, precise manner, never discouragingly. Later Brian Gibbons came to see me and designed a new mast support, then Rex Wardman joined in. I was no longer alone.

My stay in Lymington had been a good one. I had overcome the initial problems on my list and Solitaire’s engine was in perfect condition. All that was left was finance, and that was tricky as the work situation boded ill. I had no luck with my old firms, most of whom were cutting back on staff, and the Job Centre could offer nothing. The public moorings cost £10 a week and the £300 with which I’d arrived home was shrinking, so I decided to take Solitaire to Dartmouth and anchor in the river. Although an overnight stay was prohibitively expensive, it was possible to pay by the season, which was comparatively cheap, and the plus point was that I had friends there I wanted to see, and could spend the rest of my time writing.

Rome said he would sail as far as Poole with me whereupon I suggested we tack there.

‘What do you mean by a tack, Les?’

‘How about Cherbourg and back?’

The tack to France was 120 miles and so, for the first time in her life, Solitaire made a voyage with a crew of more than one. Since a boat can have only one skipper aboard, Rome got the job and I dropped a rank to first mate.

After anchoring at Dartmouth, I contacted Anne and her daughter, Susan, who had moved there soon after I had set off on my first trip. I stayed with them and Richard Hayworth, a quietly spoken man, forever throwing bones at me to growl over while he sat back with a twinkle in his eye. A fighter of lost causes with the tenacity of a bulldog but as gentle as a lamb, he was English to the core.

John and Diana Lock invited me to dinner at their beautiful home. John was a retired RN commander whose name had been given me by Caryll Holbrow in Cape Town. Later I helped crew his boat in a race but I’m afraid the round-the-world sailor impressed no one. When asked how to make the boat go faster, I said, ‘Start the engine.’ One night when I was dining with the Locks I had opposite me a very young man whom I imagined was probably still at university. He produced some cheese, which he said he had bought in France that morning. I could not work out what form of transport he had used: the time he gave for the journey was too slow for an aircraft, too fast for a yacht. Allen turned out to be the captain of the warship that had escorted Naomi James home the previous week. As a result of this fortuitous meeting, I was invited to a cocktail party aboard his ship, then the petty officers had me back next day for dinner.

In turn this led to an experience which, at the time, disturbed me. After my visit to Allen’s ship, one of his officers invited me to spend the day at the Naval College with his sister, her husband and their three children, one a baby. Despite being embarrassed by their praise of Solitaire’s voyages, I enjoyed my time with them and played a good deal with the baby whose tiny hands clung to my fingers. I started laughing.

‘She’s a beautiful baby but if she doesn’t let go of me you’ll have to take me home with you.’

The mother’s face glowed. ‘Do you really think she’s beautiful?’

‘She’s lovely,’ I replied.

‘Oh, I’m so glad. You see, she’s mongol.’

For a moment I could not take in what had been said by this young woman with a child she would care for for all its life, a woman with far more guts than those who get their names splashed in the papers.

Because I had no work, my financial situation was worsening daily. I was now pushing 53, an age which, in the electronics field, made me ancient. Many of the government contracts I tried for were of a secret nature and for a successful response you had to be British and able to prove your movements over the past three years. No employer could be expected to undertake that on my behalf.

I heard there were some mud berths at Cobbs Quay in Poole where, reputedly, the mooring fees were low, but my move there in August 1978 with £100 was to prove my biggest mistake since hitting the reef off Brazil. Not only were there no vacant berths, but those boats already there were being asked to leave because it was an ‘unscheduled development’.

Solitaire could be lifted out, her mast dropped and put in a cradle for £60 and I could live on board for two weeks. The fortnight passed without my finding work, apart from a couple of private jobs in the yard. One paid £50 and the second should have been £200 but the owner found it convenient to flit by moonlight without paying me.

In October I saw an advertisement in the local paper asking for electronic wiremen and rang the firm for an appointment. ‘I have to tell you I’m 53 years old,’ I said, having been turned down so often that I believed I had no chance.

I turned up with my last £10 note in my pocket – and got the job. If the basic wage was unexceptional, there was plenty of overtime and by saving hard I reckoned I could still leave for Cape Horn the following June. I walked and ran the four miles to and from the factory, which helped build up my legs and get me fit for my voyage. Solitaire was the one I really felt sorry for, sitting forlornly in her cradle with her mast down, dreaming of her warm bed in Hiva Oa sunshine. As winter progressed, the marina became more like a graveyard, the snow-covered boats so many tombstones.

To save money I spent Christmas in the marina, trying to hide from the manager, but he caught me on Christmas Day before I could dodge behind the tombstones. His weekly enquiry as to when I was going to remove Solitaire changed to ‘Are you still here?’ I remembered vividly my last Christmas which had been spent in Cape Town when it had been, ‘Can’t you stay longer?’ Rome collected me on New Year’s Day to spend it with his family and Annegret, a girl he had met in Cape Town, an airhostess with a German airline, who was to play a major role in my second voyage.

Work fell off after the holiday so I moved to Plessey Electronics on a six-month contract with good money and more overtime. For £25 I was offered an old banger that had six months left on its MOT and was taxed for a month. I bandaged the broken silencer but never managed to cure the carburettor, which drank petrol like an alcoholic, so I threw the bum in the dustbin and got another from the scrap yard. I needed a car for work and, more importantly, to start fetching equipment and stores for the voyage.

I drove to Derek Daniels’ home to order a second Hydrovane self-steering gear. He would service my old unit free of charge for the feedback information it would provide and I could then use it as a backup. He guaranteed the delivery date on the new one with ten per cent discount. From Kemp Masts I ordered a new Jiffy reefing boom. With this system of slab-reefing I could feed all the down-hauls back to winches in the cockpit and use the old roller boom as a stand-by. Meanwhile I had been buying ship’s stores from the supermarket, and the boat’s lockers, unlike Mother Hubbard’s, were starting to fill.

As the weather warmed I hired an industrial sander and spent my spare time on Solitaire’s topsides, finally giving her four coats of International 709 paint. I also bought some antifouling to be applied just before the boat went back in the water. This time I would not risk strangling Solitaire as I had in the South Pacific. I splashed out, too, on wet weather gear, having it heavily lined to combat the freezing conditions in the Southern Ocean.

There were changes to make on the rigging for safety’s sake. The lower shrouds of 6mm stainless steel wire had to be stepped up to 8mm to match the rest of the rigging. Sails were the major item. It might be possible to pick up some strong second-hand headsails, but I needed two new working jibs and a new mainsail, on which I held very definite views. The mainsail would be similar to the one Lucas had sent me in Australia, with a straight leech, no battens and three reef points, the last reef point to provide a virtual trysail. And I needed a heavy luff rope, not only to give strength but to grip on in icy conditions. The seams had to be wide with three rows of stitching and, had I been able to afford it, all panelling seams would have been taped with further stitching. The sail was to be at least 8oz material and heavily reinforced. All eyes, clews, tacks were to be stitched rather than pressed in position, for in the past such eyes had inevitably pulled out. My old Lucas mainsail was still good enough to serve as a backup. The working jib was to be made to the same specification apart from stainless steel, not rope, in the luffs and the piston hanks had to be heavy duty because on my last journey I had worn out two sets.

I consulted a number of sailmakers, all of whom said they could supply to specification and deliver within ten weeks at prices ranging from £400 to £500. A local sailmaking firm had several advantages: they were only five minutes’ walk from where I worked, they claimed to specialise in heavy cruising sails, their price was competitive and there were no transport costs. I called at their office on March 14th, 1979, and we had a long talk about the specifications and my reasons for them. If I paid cash with the order, the price would be £400 with delivery on May 14th.

I handed over a cheque for the £400 within a week, along with my Lucas sails to act as a pattern.

‘Do make them strong enough to take me round Cape Horn,’ was my last request.

‘We will make them strong enough to lift the boat out of the water,’ they promised. Later I received confirmation of order and delivery date.

Calling in to pick up the sails on May 14th I was told they would be completed five days later. On May 19th an employee tipped me off that they had not even been started and it was the same story on May 26th. After more phone calls and visits, I was finally told they would be ready on Saturday, June 2nd.

Handed three plastic coated sail bags, I asked to see the mainsail. At first they refused, claiming that they did not allow sails to be removed from their bags and inspected on the premises! Finally they let me pull about 4ft of the sail from its bag. The first thing that came to light was what I thought was a large tack or eyelet which had been pressed in and not stitched as agreed. Then I realised it could not be either since the material was too narrow, but could only be the head of a sail with the headboard missing! The reinforcing was limited, there was no rope in the luff, the cloth merely turned back on itself, small diamond-shaped pieces had been sewn on into which eyelets had been pressed to take the plastic slides, and the seams were too narrow. My first reaction was that I’d been given someone’s poorly-made sail by mistake.

‘You’ve given me the wrong sail,’ I complained, whereupon they asked if I had paid for the sails in full.

On affirming this I was told, ‘In that case the sails are now your property and you have no case.’

I contacted a solicitor who was also a yachtsman. He made an appointment to inspect the sails but the sailmaker failed to keep it. I contacted the Association of Sailmakers but since my sailmaker was a member of theirs, they refused to act as arbitrators. On June 27th my solicitor advised me to contact the Office of Fair Trading, at which stage I knew I had little chance of leaving for Cape Horn that year as Solitaire was not fast and we would be unable to reach the Horn before winter set in. I considered all the actions I could take, starting with taking the sails to the nearest rubbish dump and burning them.

To set off on a voyage without first class sails would give concern to my family and would be unfair both to them and Solitaire. But to walk away from the legal problem could mean that other yachtsmen would be taken advantage of, so I visited the Office of Fair Trading and stepped onto a merry-go-round until 1982, when I staggered off as sick as any long ride on the legal circuit can make you.

Once more I was to feel as if I were in hospital, this time one for the insane. Three teams of surgeons came to operate. First were the solicitors, talking softly and incomprehensibly; second were the judges, entering your stomach not with scalpels but with bare hands, twisting your guts into knots; and third were the get-on-your-bike-and-look-for-work brigade whose speciality is the heart. They remove you from the operating table and sit you in a small cubicle where a girl, young enough to be your grandchild, asks, ‘Have you looked for work? How much money do you have? Prove it!’ You are then allowed to leave their hospital, reporting weekly for your dole prescription, wishing you were a thousand miles away and had never heard of British justice.

The Consumer Protection Department advised collecting the sails and having an expert’s written report whether or not they were of merchantable quality and fit for their purpose. I was further advised to apply to Poole County Court for a hearing before the registrar, which was arranged for August 4th, 1978. The sailmaker failed to turn up. The case could now go before a judge after I had engaged an expert witness. Then my contract with Plessey’s ran out and I could not afford the repairs to get my car through its MOT so I sold it for £18. Meanwhile I had promised to leave the marina by the end of June for Cape Horn and when this fell through, I was put under more pressure. Solitaire was put back in the water and I sailed for Lymington in mid-August, entering Lymington Yacht Haven for a winter berth on September 25th. From now on this friendly marina would always be looked on as Solitaire’s home.

The court case dragged. First there were problems in finding an expert witness and a sailmaker made it all clear when he said, ‘Dog doesn’t eat dog.’ In other words doctors don’t appear against doctors, an outlook shared by solicitors and sailmakers. Since Vectis cloth had been used for the sails, I tried its makers, Ratseys, who used this as a reason for not inspecting the sails! However, they recommended I should contact the chairman of the Association of British Sailmakers, who turned out to be with Bruce Banks Sails and could not help. He recommended a surveyor who, after examining the sails, said, ‘Your troubles are over. I’ll appear for you in court.’ Whereupon he jumped on an aircraft and was never heard from again.

The court case was set for May 5th, 1980. I found another naval architect who inspected the sails and said he would appear for me. The trial went so well that at times I thought the defendant’s solicitor was working for me. When I was in the witness box he asked, ‘Did you ever write an article for a yachting magazine called “Barbados or Bust”?’ I had expected my own solicitor to bring up my past sailing experience, not the opposition.

‘Are you the Leslie Powles who sailed from England with only eight hours’ sailing experience?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Are you the Leslie Powles who was over 1,000 miles off course?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Are you the Leslie Powles who then came back to England with his tail between his legs to tell my client how to build sails?’

‘No, sir,’ I replied, ‘I’m the Leslie Powles who then sailed 30,000 miles around the world and even managed to find Australia.’

The Australia came out in that country’s accent, Austraaaaalia. There was laughter in court, the judge’s face reddened, and that line of questioning came to an abrupt halt. It was one of the few enjoyable things about the trial.

The next insinuation infuriated me. They claimed that I had become frightened to make the non-stop attempt and had used the sails as a reason not to go. Finally the judge accepted that the sails were unfit for their purpose and that the sailmaker was in breach of contract. My £400 would be returned and my costs paid, but the expense of bringing Solitaire back into a seaworthy condition was refused, the judge taking the view that these costs were in the nature of living expenses and would have been incurred at the end of the voyage.

A second blow came in one of my solicitor’s letters: ‘The court costs are limited to the appropriate county scale. We will obviously temper the wind to the shorn lamb, but in reality by the time the costs position with the Law Society is resolved you will not get the whole of your £400.’

Shorn lamb! I felt more like a sacrificial goat. By living off Solitaire’s round-the-world stores during the winter months, I managed to keep £850 of my savings, but by now we were in a sorry state. The last of the food had gone and Solitaire’s hull was covered with weed and had to be taken out of the water for antifouling. Her battery needed replacing, the rigging needed changing, and the fuel tank leaked. Time was running out.

At the age of 55, and for the first time in my life, I wanted to abandon the country of my birth. I had left England a dozen times before but never because I wanted to. Now I wanted to storm out, a spoilt child, the angry husband on the way to the pub to cool down, a feeling, true, which would pass. I was still a free man able to come and go as I pleased but this time go I would, even if it meant rowing my boat down the Channel without her mast.

Once more I started to ready Solitaire. Once more I ordered a mainsail and two working jibs, this time from Peter Lucas of Lucas Sails who, after hearing my tale, agreed to help all he could. There would be no problems over the specification; I could even have my stainless steel wire in the luffs of the working jibs. The price was the same as the duff sails, £400, with a couple of bonuses thrown in: my old sails would be checked and reconditioned free of cost and his wife would do all the running about. In fact I received a third bonus. His wife was a lovely Canadian girl, bubbling with encouragement, and I even found myself whistling Land of Hope and Glory again!

I gave up the idea of changing Solitaire from Bermudan to cutter rig as the cost was too high. The best I could afford was to step up the lower shrouds from 6 to 8mm wire, matching them with the rest of the standard rigging. I had used a local Birmingham firm when I first rigged Solitaire in 1975, so I wrote to them asking for a quotation for the stainless steel wire fitted with swaged ends. They answered by return with a price out of my reach. I had just finished reading their letter when there was a knock on Solitaire’s hull. The company’s representative had called to explain that the price was high because the firm did not do their own swaging. The rep said that since he dealt with local companies doing this kind of work he could put it through at trade cost, and he spent three days chasing back and forth. The modification still cost £85 but what really warmed my heart was that a hometown firm had gone to so much trouble. I still had to change the rigging connections at the top of the mast but that was only a day’s work.

A ship’s battery, something I could not take chances with, cost £80. Solitaire’s motor can be started by hand but only with difficulty, and after months at sea I thought I might be too weak even to try swinging it. New halyards and sheets took another £75. Rome managed to buy charts, almanac, radio and navigation books through the RAF at a discount, but it was still a drain. Some of my original charts could be used again. At one stage Rome pointed out that I had no chart of Australia, which led to our having words. ‘Since I’ve no intention of going within 200 miles of that coast I don’t need a chart,’ I told him. Rome finally walked away shaking his head after my last remark that it was six months away, and I’d worry about it when I got there.

The problem of lack of money was forever raising its head, not simply because I couldn’t afford to buy the things I needed but because I had tried to prevent friends realising just how broke I was. Peter and Fanny Tolputt, who owned a local guest house, took me along to the wholesalers for stores, where I spent £120 buying the cheapest food I could find. They were convinced that I just did not like tinned steak, duck or salmon! At the very least I needed to buy double the amount of food already on Solitaire, the eight connections on the mast’s top rigging had to be changed (say £60 for that) and I had to buy at least one used headsail for running before the winds in the Southern Ocean.

Each day I rang my solicitor’s secretary (her boss had long since stopped talking to me). On June 10th, with less than £100 in my pocket and two weeks to Solitaire’s departure, he wrote me from his office in outer space and I stopped whistling Land of Hope and Glory.

‘Dear Mr Powles,’ he wrote. ‘I refer to my secretary’s recent call from which I gather that you are not minded to return the sails until the question of costs is resolved.’ Then came the body blow. ‘Unhappily I have to report that the other side have not been prepared to agree costs which will therefore have to be taxed by the court. This process will take at least three months and there is not the slightest prospect of resolving this matter before your intended departure this month.’

I was no longer the angry husband slamming out of the house. Since I had been rejected I would look around for other attractive company with whom to have an affair. I remembered all my American friends and the kindnesses they had shown me on my first voyage. July 4th was their Day of Independence so it would be mine, too, mine and Solitaire’s, the day we would sail.

Perhaps at this stage a normal individual would have considered finding a sponsor, but I was dead against it, my feelings stemming, perhaps, from my working-class background. With a sponsor’s money I could have a yacht built with electric self-reefing sails, sensors that would record any strain and reef the sails while I stayed below watching the latest video, relaxed in the knowledge that our satellite navigation aid was keeping us on course for Cape Horn. Without a commercial sponsor I would be cold, hungry and afraid, but I would be using the gifts given to me by the only sponsor I was responsible to.

The closest I came to being caught in this rat race was when I met Dr Herbert Ochs, who came to see me about using a new antifouling he had invented. A chubby, jolly man, he must have been a bit older than me. I liked him on sight, a down-to-earth character I could have spent days talking to, a man I could trust to keep his word. When I told him my feelings about sponsors he said, ‘There’s no question of your considering me a backer. I simply want you to put a gallon of my concoction on Solitaire’s hull, take it round the world non-stop and let me inspect the results. Er, should you hit a reef, run aground or sink I’d be grateful for any last minute photos you manage to take.’

While we talked in the cabin I worked on my old plastic sextant, which still had the handbag mirrors I had stuck on in Panama. The adjuster had been held together by elastic bands, now perished, and I was replacing them with the finest money could buy.

Dr Ochs, or Herbert as he had become, grew more and more agitated. Unable to contain his curiosity any longer he asked what I was doing.

‘Getting my sextant ready for this trip,’ I replied, whereupon he turned a lovely shade of green.

‘Not with my ............ antifouling you’re not!’ he exclaimed. He promised to replace the sextant and a week later turned up with a beautiful Zeiss product. After much discussion I agreed to accept it on the understanding that when I returned, Solitaire would be taken out of the water to have her hull inspected but that I would not be required to express an opinion. I felt thoroughly ungrateful but I did not want to be obligated.

Lymington Yacht Marina allowed me to haul Solitaire out of the water early on Saturday morning and leave her in slings until Monday. This kept down the costs and was far more efficient than rushing the antifouling on a six-hour tide at the Town Quay.

Rex drove me to Birmingham to farewell my family and leave the duff sails with Tony and Irene Marshall. If they had heard nothing from me after a year the sails were to be sent to my solicitor, otherwise I’d deliver them myself when I returned and carry on with the court case.

Driving back to Solitaire all I could remember was my father’s big, rough hands, my mother’s frightened eyes and her last words, ‘Keep warm and be sure to have plenty to eat.’ I would remember those words later!

On my return to Solitaire I entered the half world that I knew well from past voyages. Normally the transition was made one or two days before sailing; this time I had been slipping in and out of it for two years. I badly wanted to hold on to what people said to me, record them on tapes in my mind to be taken out in the months ahead to be used, gone over slowly and to enjoy when I had more time to think. But life became more and more difficult as there seemed so much to do in so little time and questions merely served to trigger more problems.

The July 4th departure had to be postponed. Keith Parris became my unpaid, uncomplaining press agent. He and Anne were two people who sneaked up on me and I can’t now remember when I first met them. Both were schoolteachers who owned a boat in the marina, Keith with time on his hands. Without really being aware of it I began to rely on them more and more as my sailing date neared.

A couple of nights before I sailed, Rome and Annegret threw a party for me at which were his mother Grace, his sister Terry and her husband Martin. All had presents for me which, since it was late, Rome would bring to Solitaire the next morning. Sure enough Rome and Annegret turned up and loaded an unending stream of parcels. I could not really appreciate it all, staggering over water containers and trying to store the presents on top of the bunks. Annegret excitedly tried to explain that for weeks Rome and she had been making ten of the parcels, which were to be opened at different stages of the voyage. One was marked ‘Crossing the Equator’, another ‘My birthday’, besides ‘Rounding the Five Southern Capes’, ‘Christmas’, and so on. Over the coming months I tried to log just what these parcels meant to me. At one stage tears of frustration streamed down my cheeks, unable to transcribe my feelings into words. In the end all that would be written was, ‘God bless them’.

On my last day there was another rush of gifts, mostly paperbacks and food. A parcel from Peter and Fanny included a tin of salmon and a bottle of champagne for rounding Cape Horn, and two fruitcakes, ideal for the early days at sea. A Dutch friend had somehow obtained ten boxes of NATO army rations, each box supposed to last 24 hours. From the local bakery I had bought 70lb of flour housed in two 5-gallon sealed containers. Another container held 5 gallons of sugar! A last minute purchase of 30lb of onions, another of potatoes. Fanny gave me three dozen fresh farmhouse eggs. I had food enough for a six-month voyage. With help from my guardian angel I would be at sea for nine months... I was saying ten, by the end of which I would surely end up looking like Twiggy.

The morning of July 9th, 1980, brought light northerlies and a few scattered clouds in an otherwise clear blue sky. I had been up since dawn, Solitaire becoming the stage for a farce I played every time we sailed. Before learning this game I would get into all kinds of trouble trying to do three things at once while carrying on as many conversations. The engine had been run and was still hot, but this did not prevent my remarking, ‘I hope the motor starts, otherwise you’ve come for nothing.’

Rigging, halyards, sheets and sails had been checked a dozen times but I still walked the decks, pulling and kicking things as though seeing them for the first time, allowing me to concentrate on the things that really mattered. Will the wind push Solitaire onto the berth or away? How will the current affect her until she attains speed and can be steered? I wanted to say nothing that would leave behind a bad impression because the next day I would not be there to say I was sorry.

In Tahiti I became close to an American family whose daughter would row over each day while I was at work and put a letter on the chart table for me to find when I arrived home. On the morning I sailed she was there with a garland of island flowers. As I put out to sea I turned for a last wave, the flowers still around my neck, and remembered that today was her seventh birthday. I had planned it for ages but at the last moment had forgotten. I could not turn back, too many people had come to see me off. The voyage to Australia lasted 69 days and that’s a long time to be sorry.

After preparing Solitaire for her departure it was the crew’s turn, another ritual carried out before each voyage. My thinning ginger hair had given up the ghost the night before when Annegret had butchered it in (what else?) a crew cut. The pasty white body scaled a grossly overweight 14 stone – for the first time something to be pleased about since it could live off its own blubber during the early stages of the voyage. And it had delighted in its last soaking in fresh hot water, where pores had opened and been cleaned. From now on there would be showers direct from the sky but the pores would always contain salt. I dressed in clean clothes. The day before, my laundry had been done. I wore my oldest gear, keeping the best for the long months ahead.

At 8.30am on July 9th, I walked down the pontoon to Solitaire. All I had in my pocket (in fact all I had in the world) was £60, of which £40 had been given by a TV company a few days before. They had promised £20 at first but after the recording had doubled the amount. With a few violins it might have been further increased. On my return I learned that they had interviewed another singlehander at the same time and put us both on the same show. The difference was that the other chappie was sponsored. His yacht had cost £350,000 and a further £40,000 a year to run but the funny thing was that after all the money and shouting he never even sailed!

Solitaire waited for me to step aboard, her old red ensign now a faded orange, her spray dodgers dirty and rust-streaked, her new golden boom with an unused mainsail, her old number two genoa hanked on to one forestay, the new working jib on the other.

These I could see as the visitors saw them, perhaps shaking their heads, believing me foolish to set out on such a voyage so ill-equipped. It was what they could not see that would have convinced them I was mad, the equipment I lacked that most sane yachtsmen would require for a voyage across the Channel, let alone around the world: liferaft, radio transmitter, barometer, flares, charts, wind speed indicator. The list was endless. A sane person would work out stores he needed, then double them. I had worked it out and halved it, not from choice, but because I had stopped being rational after depending on others for justice and fair play.

Aboard Solitaire things speeded up. A quick interview with a TV crew, Keith Parris saying they would follow me downriver in the marina launch for last pictures, them asking if I would put full sails up to leave the mooring, and I explaining that I would have a following wind and could not. Once clear of the berth I would put up the genoa, leaving down the mainsail until we reached the Solent.

I looked for people I could trust to let go and spotted Peter Tolputt and Margaret Brown. A shout to Peter, ‘Will you take in my fenders?’ then to Margaret, ‘Please take in our springs.’ A dash to start the motor. Back on deck, collect the fenders, drop them below. ‘Peter, the motor’s on slow ahead. Will you let go our bow line then come back for the stern?’

At 9.15 Solitaire severed her links with land for 329 days. A quick wave to Rex and Grace. ‘Tell Rome I’ll see him in ten months’ time.’ (He had a flying detail that morning and could not be present.) Hard over with the rudder to pass between the other row of berths, then heave up the genoa which, with my excess weight, went up easily without need of a winch handle. A quick chase up deck when its sheet snagged. Waving to friends on other yachts then into the river, pursued by the Yarmouth Ferry and the TV crowd, trying to take instructions from one while not being sucked into the other.

Then my own request to Keith, the last for 329 days: ‘Phone Mom and Dad and say I’m on TV tonight.’ Their shouts of ‘Good luck’, before they turned back to their safe homes.