Lymington – South Atlantic

July – September 1980

Solitaire cleared Lymington River into a surprisingly empty Solent and headed for the Needles. Her new self-steering gear had its bright red wind vane set for the first time, already proving it was more sensitive than its predecessor. The trailing log’s spinner was put over the side, registering more miles to add to the 34,000 already recorded. Our new mainsail was hauled up, the reefing ropes passing through eyes on the leech of the sail then back through the boom to a block on the foot of the mast, thence to a winch in the cockpit, all designed to make reefing easy. It snagged but needed only a small adjustment. Nevertheless I was glad I hadn’t tried to be too clever while friends were around. With the main up more contrasts: pure white against patched grey.

The lines that had tied Solitaire to shore now secured me to her, as a priority on leaving harbour was to run them from cleats in the stern along the deck to a bollard in the bow. In the old days I would step into the cockpit and secure my lifeline, but for this trip I had taken another precaution: a large U-bolt had been put within reach of the main hatch so that I could fasten on to this in rough weather before leaving the cabin.

Approaching Hurst Castle there was time to nip below to check for leaks, grab my wet weather gear and get back to the cockpit with a few minutes to relax and catch my breath. Broad reaching up the Needles Channel to the Fairway buoy, I eased Solitaire onto 254° by adjusting the self-steering vane and hauling in the sails as we came onto a spanking reach, day and wind both perfect. I should have stopped the motor and used the large genoa but decided to leave well alone. Maybe I was lazy, but the number one genoa would have restricted my forward vision, and anyway it was best kept for future use. There was a good reason for running the engine: I needed a fully-charged battery to power my navigation lights and give me a better chance of dodging shipping. But the main reason was to reach the open sea. Already I was feeling the old freedom and no longer responsible to the laws of the land. There were no courts of law out here, and if I made mistakes they would be mine with no one else to sit in judgement. Just God, Solitaire and me.

Every voyage consists of steps. A year before, when I believed we would be making the voyage fairly well equipped, there had been only two: England to Cape Horn, then an easy step home. Now the steps had become more of a drunken stagger to provide for possible trouble. First, clear the English Channel, then cross the Equator to Ascension Island where, if the rigging broke, the Americans would help. On to Cape Town and the Royal Cape Yacht Club where I could carry out repairs. In Australia, if I had to, I could buy more food and still round Cape Horn. The Falkland Islands, even if I arrived under jury-rig, would allow me to fix up something to get us home. All vague thoughts. Privately I intended sailing around Cape Horn non-stop even if I finished up eating stewed boots and barnacles. Solitaire might have to give up if the rigging broke, but as long as she kept going I would not be the first to throw in the towel. Not that she had any thoughts of giving up: romping along, throwing spray in all directions, alive for the first time in months, her joy was infectious.

I started to straighten up the cabin. The two bunks looked like a double bed, singles joined by the water containers, so I completed the picture by spreading my sleeping bags across them. At the back of the containers was about a yard-and-a-half of floor space, enough for a bit of disco dancing but a tango was surely out. For a moment I was taken back to South Africa and my first thoughts about sailing when I had told people I wanted a boat to carry me, my suitcase and a set of golf clubs around the world, although then I had not meant non-stop. Here I was setting up another record: the first round-the-world non-stop yachtsman to carry golf clubs.

Back in the cockpit with tea and cake I watched a coastal steamer change direction to head towards us, the crew lining the decks and cheering. After waving back with the tattered remains of my red ensign I decided to stow it away and bring it out only for important occasions. The day stayed warm and pleasant, the land standing out clearly but in my wet weather gear I became tired, hot and happy, and to the slow beat of Solitaire’s motor drifted in and out of sleep. By early afternoon we were 6 miles south of Portland Bill, 34 miles in five hours, not bad going considering the weighty stores on board. Start Point light came in view at 12.10 Thursday morning, July 10th, our last view of England for nearly 11 months.

In the first 24 hours we knocked off 125 miles en route to Ushant; it was 75 miles away and took another 12 hours. At first I thought our navigation had been spot on. I had intended passing no closer than 5 miles then to bring Solitaire hard on the wind to cut through the shipping lanes out into the Atlantic before coming onto our southerly course, but the land drew closer and buildings, including the lighthouse, came into sight. Blast, I thought, annoyed with myself. This was downright lazy sailing, dozing when one should have been taking RDF bearings. Ushant was sighted at 9.15pm that Thursday, 36 hours out of Lymington, the last land I would see for 326 days. As darkness fell, coded flashing lights from the lighthouse slowly worked their way to Solitaire’s stern, then became just a loom on the clouds as man-made lights disappeared, to be replaced by nature’s.

Heavy shipping cut off our retreat from the possible storms in Biscay to the open Atlantic, their steady stream of lights making our sail more like a quick dash across a motorway than a safe withdrawal from danger. A ledge runs around the Bay of Biscay and when seas hit it terrifying waves can build up. The quickest way to get off this ledge was to cut straight across. With constant winds from the present westerly direction we would have them just forward of the mast, making for a fast passage, but it meant staying inside the shipping lanes. Even so I could still snatch a few hours’ sleep in reasonable safety. I set Solitaire’s self-steering to head us 50 miles west of Cape Finisterre, 360 miles across the Bay, and slowly the lights of the ocean-going ships dropped below the horizon. After seeing nothing for an hour I went below to eat, and then to lie on my bunk to think of family and friends.

It has always amused me that on my return from a long voyage I am an immediate expert on loneliness, which bears no relationship at all to being alone. Loneliness is caused by people and places and the real experts are the old-age pensioners who wonder why the children call only once a fortnight and then can’t wait to leave; the people with families who wake up one morning to find they have nothing, not even each other. Loneliness is staring into other people’s windows at Christmas time, and thrives in railway stations, in airports and divorce courts, but you are never lonely because you are alone. How little people know about themselves surprises me. Few have been alone for more than a few hours, and yet they claim they could never survive so many weeks by themselves at sea because they confuse missing someone with being alone and lonely. I did not miss my family and friends because I simply took them with me and had time to remember them and what they had said, which is no different from re-reading a good book. Indeed in some strange way I became even closer to them at sea.

I had known the other side of the coin: leaving my family to join the RAF, for instance, and a railway station in Toronto when my first wife returned to England. Perhaps the loneliest experience of all is being with someone who no longer wants to be with you.

Friday morning found us 250 miles from our home port ploughing into a choppy sea in a light drizzle with poor visibility. I was still using local time in the log, navigating with RDF bearings on Cape Finisterre and dead reckoning. Once the weather cleared I would change to Greenwich Mean Time, take my sun sights and log our position every noon. The day was spent sorting out food, which even now seemed to be shrinking as I stored it away. Even the number of paperbacks diminished as I sorted them into boxes. When they had been given to me I had said, ‘I hope you won’t mind if once I’ve read your book I dump it overboard.’ As I normally read a book a day the idea of dumping was already forgotten. I planned to read the best first and keep them for an encore towards the end of the voyage.

The food situation was far worse than I had imagined, even though before leaving Lymington I had estimated that the stores would have to be doubled to ensure a non-stop voyage. When I started to receive presents of food, things began to look up and by sailing time I reckoned I had enough to provide a meal a day for nine months. Only when everything was listed and stored did I realise how serious the food problem would become after reaching Australian waters.

Flour 70lb in two 5-gallon plastic containers

Sugar 60lb in one 5-gallon plastic container

Rice 60lb in sealed buckets

Eggs 36, onions 36lb, potatoes 20lb

Coffee and tea posed no problems, because at worst tea bags could be used twice. I had ten food parcels from Rome and Annegret, ten NATO 24-hour rations from my Dutch friend, two fruit cakes and other bits and pieces for special treats.

My diet would be easy to work out, prescribed as it was by the provisions themselves and the time they would last. In the past I had baked six bread rolls every three days. Until we were halfway round, say five months, I could carry on doing that, but after five months at sea the yeast would be useless. So bread would be a basic food until Australia when any remaining flour could be used for pancakes. On the other hand rice would last for ever so it had to be kept for the second half of the voyage. The voyage’s first turning point would be when we passed under the Cape of Good Hope, 65 days away if we averaged 100 miles every 24 hours. Meanwhile I could have an egg every other day! Onions last well and make spicy sandwiches with Marmite or Bovril. I intended using the NATO rations early on, since they were a bonus, and the first of Rome’s parcels on crossing the Equator. Rivers of rain water, running down the mainsail to cascade off the boom end like a broken house guttering, would ensure a water supply. As we carried nearly 80 gallons there was no need to replenish until we were homeward-bound.

The winds were from the west just forward of the beam across a flat sea as we approached the middle of Biscay Bay with 2,000 fathoms of water beneath us. Saturday, July 12th, our third day at sea, I spent adjusting the rigging and making up a new kicking strap. I had Peter and Fanny’s salmon for dinner that night accompanied by onions and boiled potatoes.

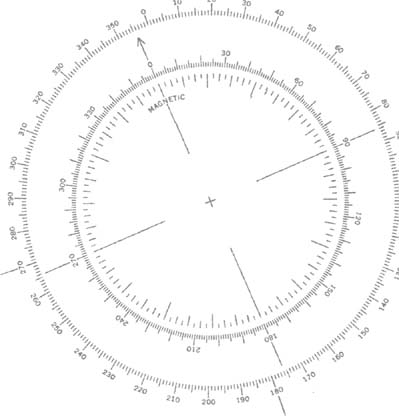

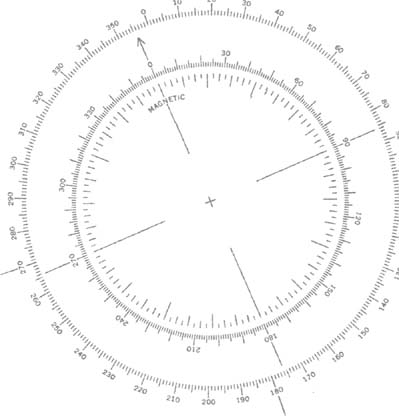

On Sunday the weather brightened and I brought Solitaire hard onto a light Force 3. I should have hoisted the number one genoa but there are times when things are so perfect that you hardly breathe lest you spoil the balance and speed seems of no importance. For the first time I removed my wet weather gear and shoes and socks. Freedom! I changed the ship’s clock to GMT and at 7am took my first sun sight for a position line and made a cross on it after my noon sight for latitude. Thanks to my new sextant I had no more worries about loose handbag mirrors or whether the elastic bands would hold long enough for me to take a sight. More freedom! Catching the sun in its flight and controlling it in a slow descent onto the horizon I turned the delicate micro adjuster with reference, like a jewel thief about to break into a safe. A perfect day with a perfect end: stew with extra potatoes for dinner.

I was wary of saying in the log how well things were going because when you are on top of the world, and start shouting about it, someone inevitably comes along to knock you off, but my extended stay ashore had made me forget that lesson. My feet started to slip early on Monday morning after I had woken to find strengthening wind, breaking seas and poor visibility. By noon we had two reefs in the main with the wind backing south-west, and were being pushed towards the land 30 miles away, Solitaire taking punishment as she tried to smash through fast-breaking waves. If we continued on our present course we would soon be in the shallower seas around Cape Finisterre. When night fell phosphorescent seas continuously buried the boat, allowing her only seconds to clear herself and gasp for breath.

Her surrender, when it came, was not because of any lack of determination on her part. On a brief visit below I found seawater streaming down the mast support and believed that the deck had cracked. It was my first panic of the voyage. I had to take the pressure off her but as I dropped her reefed sails she came beamon to the seas, which slammed into her side. She rode the blows, giving ground and heeling to protect decks. With Solitaire looking after herself I made a closer inspection of the damage by torchlight. The mast is deck-stepped into a shoe secured by six bolts through the deck onto a steel plate and the top of the keel. After wasting time trying to find the source of the trouble I pumped out the bilges and lay down to sort out my thoughts. Had I put sealant on the securing bolts?

With dawn on Tuesday, July 15th, came light and lovely north-westerlies. I discovered that the mast shoe itself had cracked, but by making a plate to fit over it I felt confident we would see the last of the leaks from that direction. I was unable to get a morning sight due to overcast skies, but by noon they had cleared and the latitude taken put us approximately 60 miles west of Cape Finisterre. My log for the first six days showed 632 miles, despite making only 35 in the last 24 hours thanks to the storm but we were still ahead of our 100 miles a day target to the Cape of Good Hope.

That night I wore pyjamas for the first time on the trip. When a few gusts of wind threw Solitaire off course, I removed them to go on deck wearing just a safety harness. Having dropped the mainsail, I replaced the pyjamas and snuggled back into my sleeping bag listening to the contented murmurs of my faithful companion no longer fighting the sea but living with it in peace.

Our first week at sea ended on Wednesday, July 16th. By noon we had logged 750 miles. I should have reset the main, but on broad reach, with just the number two genoa up, it would have blanketed the jenny as I had no whisker pole to hold the headsail in position and it would have slammed every time a wave passed under us. Normally this is acceptable but as the genoa was already weakened I did not want it to take too much punishment. I started to realise how different things would have been with a new number two jenny. Ah, well!

For all that, I was happier than I had been since completing my first voyage. Solitaire bubbled along, sharing a contentment that came from doing what you wanted to do in ideal surroundings. At the day’s end a simple meal. Margaret had given me bread rolls that could be popped in the oven and baked, and as each NATO pack contained a small tin of cheese, hot baked bread, cheese and onion followed by delicious coffee, it provided all I needed. As I watched the sun set, my cup and belly were full. Deep satisfying sleep!

In our second week we covered 780 miles and the log is full of contented entries. It was not simply finding one’s sea legs, the pleasure went deeper than that: it was a feeling of belonging, of walking into a strange room and knowing that you have been there before, of meeting a stranger and recognising a mutual bond without a word being spoken. To have taken me from the sea and placed me in a square box miles inland would have brought as much confusion as if you’d done the same thing to Solitaire herself. That week’s log read:

Thursday, July 17th. Eighth day at sea, good night’s sleep. Not a cloud in the sky. Winds light from north-east 3 to 4. Number two genoa only as, with main up, it is blanketed causing it to slam and wear. I’m not complaining, guardian angel working well. Distance last 24 hours, 124 miles.

Friday, July 18th. Ninth day at sea. Wind about 25° off the stern, should do more sail-adjusting but content to read, eat and sleep. Logged 986 miles, 112 miles in last 24 hours. Position for the amateur yachtsman, 170 miles due west of Lisbon. Big head!

Saturday, July 19th. Tenth day at sea. First 5 gallons of water used. Winds becoming lighter. Have hoisted main and tried to use the heavy aluminium pole to hold out the genoa but too much strain on the sail. Lovely warm conditions. Winds from the east, Force 3. Few scattered clouds. On book five. Very happy. Logged 104 miles in past 24 hours.

Tuesday, July 22nd. Thirteenth day at sea. 0915 Madeira approximately 35 miles to port side. Starting to warm up, could be changing to shorts tomorrow. On my sixth book.

Wednesday, July 23rd. Fourteenth day at sea, 1,530 miles travelled, 109 miles a day average, better than expected. Celebrated by using two cups of water to shave and trim my beard and wash all over. Basked in the sun in shorts with a cup of delicious coffee.

The following week brought sunburn, progress and setbacks: the first because I spent too much time in the cockpit wearing only shorts; the second when we passed 110 miles west of the Canaries; and the third started on Saturday, July 26th. First the skies turned grey, giving the impression an atomic war had just finished. For a while we had a milkily faint sun, then the wind started to increase, gusting from Force 6 to 8 with Solitaire surfing on a broad reach, the odd wave breaking over her. I should have changed down to the working jib, but I thought I’d try for a fast sail to make up for two days’ lack of wind. And make up for it Solitaire surely did with a run of 141 miles. Sunday night was a bit hairy with Solitaire still going like a dingbat, the old genoa straining out its heart to keep ahead of breaking seas.

I had been checking the sails during the night with a torch, but when dawn broke on Sunday I saw that the 2-inch seam along the bottom of the genoa had ripped and was trailing over the side: I replaced it with the working jib and hoisted the main when the wind abated. The rest of the morning was spent repairing the genoa by folding the seam twice and wrapping it in the first panel of the sail. The log, however, showed that our mad ride through the night had given us a run of 121 miles, a ride I was to spend two days paying for, sewing sails until Monday night. From now on I would treat the number two genoa as though it were spun from pure gold for use in ultra-light winds only. On Tuesday, July 20th, I started to record the sails I should have had, with a feeling of having let down Solitaire, asking too much of her without giving her a fair chance. By noon that day the log read 2,175 miles, 86 miles in the past 24 hours:

Conditions a little better. Hazy sky. Pretty good sights. Will continue heading westerly to clear Cape Verde Islands. Number two genoa in use with main. I’m afraid we have little chance of establishing any records thanks to our lack of sails, poles, etc., but happy to potter along in my own sweet way. Still not eating much, but thirst back with a vengeance. So far have eaten four tins of fruit and have been swilling down Margaret’s fresh fruit drinks. Antifouling coming off self-steering blade. No undercoat applied could be the reason.

Wednesday, July 30th. Despite the ripped sail we have still managed 760 miles this week. Have cleared Cape Verde Islands, and now on course 220°, blue skies, lovely weather. Solitaire broad-reaching well. Genoa seems OK after repair. Will not mess about with poles any more but keep them for jury-rigging (I hope not!). Still not eating well, another tin of stew yesterday followed by tinned grapefruit. I should be baking bread but the thought turns me off. I can’t understand my lack of appetite. It could be the 25,000 miles still to travel, missing friends, concern for Solitaire and her lack of equipment. Perhaps it’s reaction to delay in starting the voyage, or just my oversize waistline bouncing about. I’m even worried it might mean the start of appendicitis. I’m not lonely, I’m enjoying the voyage. Maybe with a few more miles under our belt I’ll start eating. We have RDF signals from Cape Verde Islands so no navigation problems. New sextant works like a dream. 1340 GMT: noon position 31°N 24°50’W, log reading 2,291 miles, 116 miles in 24 hours, which could have been much better with decent off-wind sails. Will bake bread for the first time, lovely with sandwich spread and fresh onion. We are 250 miles due north of Santa Antao, Cape Verde Islands. Should clear on this tack with luck. Going well. Good old Solitaire.

This was one of the longest entries I have ever made in the log. I was confused by my feelings and thoughts but by putting them into words they would perhaps sort themselves out. When I lived in Canada I had a similar experience and went off my food for no reason at all. On my return to England I found that my mother had been seriously ill then; I had not been told to save distressing me.

The damage to our only reasonable running sail was a setback. If we had nothing bigger than a working jib in the Southern Ocean we would be cutting speed by a third, but none of this accounted for my unease. Before setting out I had estimated my chances on a voyage of some 28,000 miles. I believed that with the strong winds in the Southern Ocean pushing us along we should make our 100 miles a day, say 270 to 290 days at sea. The difference between a broad reach in Force 5 to 6 using a genoa (140 miles on a good day) and smaller working jib (95 miles a day) was 45 miles. But the longer we spent at sea the more chances there were of the rigging going and I was uncertain how long the masthead connections would last. From the records of other Cape Horners I knew I could expect at least one roll over; one roll over Solitaire might survive, but not two or three. I had known this before leaving and accepted the risk, so I could not understand my new apprehensions, or why I had become so finicky over food, eating tinned stews and fruit, which should have been kept for the later stages of the voyage.

July 31st, saw the start of the fourth week at sea, with flying fish rising from under our bow. I have no idea why they were so called as they don’t flap wings but simply leap along the tops of waves to get up speed, then launch themselves into the air to glide on delicately transparent wings. There’s intense pleasure in watching them, particularly when a setting sun showers them with colour, and I felt like apologising as Solitaire’s eager surge displaces them in a shower of noise and panic. By night they flew into the sails. In our early days I would crawl about in the dark trying to reunite them with their families but they damaged their wings too badly to return them to the jungle that is the sea. I remember holding one, its eyes popping, gasping for breath, or should that be water? I heard a voice say quite clearly, ‘Don’t just lie there, say something’, and was even more surprised to realise the voice was mine. I believe they lock away people who talk to fish. That Thursday there were six on deck, a record. I have read of seamen breakfasting off them, the fish fried in butter with browned potatoes and onions to accompany them. Had they been served that way I would have eaten them with relish, but having heard their death struggles my entry in the log simply read, ‘Six large flying fish came on board during the night. Very sorry, I hate to see anything die.’

By that point I was on my eighth book, The Master Mariner, one of the finest books I have ever read. Its pages would become worn as I read and re-read it.

‘Friday, August 1st. Grey skies, sun about to pass directly over my head’, was all I noted. It would be two or three days before we could get a decent sight for latitude. We would then be facing north when we took our noon sight instead of south, which I would have to watch out for when applying declination, remembering my first boob and my subsequent appearance in a Brazilian maternity hospital. I made a large note of the change in the ship’s log.

Next day Solitaire was approximately 100 miles west of Santo Antao in the Cape Verde Islands. Because the noon sun was still above us I did not try to pinpoint our latitude. What interested me was Solitaire’s longitude, 27°45´W. After leaving England Solitaire had headed south in a gentle westerly curve to sweep around the tip of Africa and the Cape Verde Islands. Now that we were well clear, we could start to swing back for our first major turning point, the Cape of Good Hope.

On Sunday, August 3rd, the sailing was marvellous, with Force 3 easterlies, the waves small compared with the past weeks perhaps due to their coming from the coast of Africa and feeling its protection. Blue skies with a few scattered clouds to make it interesting, but no dolphins. I remembered reading that Japanese fishermen were killing them off by driving them ashore. Bloody fishermen, I muttered. I started drinking tea again after two weeks of not being able to stand the stuff. And a further note, ‘Remember, clown, that the sun is now north of us.’

Next day, calm conditions gave me a chance to lean over the side and check the antifouling. There was no slime or growth, although the paint had changed in colour from a reddy brown to light fawn, the seas having stripped the topcoats. I checked the motor, sprayed it with oil and turned it by hand for the first time in three weeks. I was saving it for the doldrums we would soon be entering. As I was taking my noon sight my old pals, the dolphins, showed up for the first time, so the bloody fishermen had not killed them off after all. To prove the point they came back again that night to put on a special performance. The last two days of our fourth week brought lighter winds and slamming sails in a high swell, a final day’s run of only 44 miles. Nevertheless we still managed to make good 692 miles for the week, 2,983 miles in 28 days. Not bad going.

On the last day of our fourth week something terrifying happened. We sighted our first ship for two weeks, not that that scared me. I started the engine and the fan belt broke. That did not worry me either as I soon fitted a spare. By afternoon the wind had dropped completely and I was forced to lower all sails. Then I found that I had read 19 of my supply of books. None of these things caused much concern. But what did petrify me was that I nearly committed hara-kiri by ripping open my belly. It was one of those stupid things you do when not concentrating on your job. I had been trying to cut a piece of canvas with a particularly sharp knife and, like a fool, was cutting towards me. The knife slipped and next second I was looking at a 6-inch pocket I had made in my shorts. When I removed them I found I had blood running down my stomach. Fortunately it was only a scratch, but half-an-inch deeper and I could have been in real trouble. Three inches lower and I would have been the laughing stock of Birmingham.

‘Why did you give up sailing round the world, Les?’

‘Well, I cut my thing off!’

Perhaps one should not curse the Japanese, even if they are slaughtering your friends.

We had now reached the stage in the voyage when life began to speed up. I’m often asked how it is possible to spend week after week living in boredom. Most people on holiday find that, although the first week goes fairly slowly, the longer they are away the faster the time flies, particularly if they are enjoying themselves. It’s the same with sailing. You wake and perhaps bake bread, take the morning sight, have a coffee, read a book. After noon sights, the main meal. More reading in the afternoon followed maybe by a bit of a snooze. Watch the dolphins play with a last coffee. Another day has passed. Work and storms interfere with this fast-moving clock. In moments of danger it stops to freeze you in a lifetime’s terror.

Wednesday, August 6th. The start of our fifth week at sea, our latitude 12° north of the Equator and longitude 27°W. Another 720 miles to Rome’s first parcel for crossing the line. We start edging to the east to sail down the middle of the South Atlantic, reducing the longitude to around 20°W. No point in heading for the Cape of Good Hope because a large, high-pressure area lies off the coast of South Africa. Better to stay clear of its calms, not that there would be much chance of a direct passage anyway. Since leaving England the winds had started from the west and slowly veered, moving clockwise to north then north-east, giving lazy days of sailing with stern winds. Now they were blowing from the east. The doldrums would bring confusion to the winds. It would be possible to have days, even weeks, of calms to be broken by squalls, short sharp gales from every point of the compass. Flat seas, angry seas. You paid your money and took your chances. Once through the doldrums the wind should settle, blowing constantly from the south-east, and the Cape of Good Hope, our next turning point.

Whenever I think or write about the weather my thoughts seem always to affect it. After writing in the log that we would soon be in the doldrums we lay in a sea of grey steel. Every now and then someone would shake its corner, making it swell and ripple. We spent the night with just the reefed mainsail up. Even so there was much slamming and banging, and for all the noise we covered only 4 miles, and lost two of our three buckets. How I could be so stupid as to lose two buckets one after another I have little idea. The handle came off one as I was trying to bring seawater on deck and fell like a leaf through the transparent blue water. Without more ado I tied a second bucket to a rope and dropped it over the side with the same effect. Neptune must have thought it was raining buckets but at least he had a matching pair. The last bucket now took on a new importance. Although I had a flush toilet on board, once in the Southern Ocean, with its high seas, it would be more sensible to close it down at its seacocks and use a bucket. Fortunately the remaining bucket was stronger than its companions so I thought it should render valiant service.

Thursday night brought a vicious electrical storm with black, racing clouds, breaking waves, skin-smarting driven rain... and our first visitor, an unwelcome one: a butterfly, in the middle of an ocean, bringing only sadness with it for its certain death. As with land birds they last only a day or two as you try to feed them, but they always die. Sometimes you wake in the morning and they are lying stiff on the cabin floor. At other times they disappear and you feel thankful. Days later you move a book or a chart and you find their lonely grave. It’s difficult for people living ashore to understand the effect of such a loss. Unlike the human race a single small bird becomes your responsibility; you share in its suffering, it’s the only living thing with you.

We had been in the storm for some time. Angry seas tore furiously towards us, breaking over Solitaire’s bow and flooding her decks. The night sky, lit by a full moon and hundreds of bright stars, was brilliant. It is only when you watch awhile and notice how quickly moon and stars are being switched on and off by racing clouds, fronts rushing through like stampeding herds, that you understand. I reduced to two reefs in the main with working jib and decided that before enjoying a hot drink below I would first clear up the tangled mess of halyards and sheets in the cockpit.

I bent to pick up the ropes and came up with a screaming monster in my hands. Jesus Christ! I flung it as hard as I could. Only when it hit the boom and its wings splayed out did I realise it had been a storm petrel. I watched it fall into the sea with horror. I had committed murder and the loss of this bird was to stay with me for the rest of the voyage. I would be reminded of it every time I saw other birds gliding past Solitaire’s white hull or landing in her sheltered wake.

Saturday, August 9th. One calendar month out of Lymington. Still making progress in squalls and confused sea with runs of 60 to 100 miles a day. Hard on the wind most of the time with plenty of tacking back and forth.

One night when we were hard-pressed I heard two loud bangs like a gun going off. I dashed on deck thinking the rigging had parted. By the time I had reached the cockpit, the thing I used for a brain had already accepted the fact and was calculating how to reach Ascension Island under jury-rig. The rigging still stood and I could find no reason for the double bangs. I had heard aircraft flying through the sound barrier and this had sounded much like that – a cannon exploding followed by its echo. Possibly it was a high-flying jet or even a satellite passing overhead at 100 miles a minute, making unflattering comments as we crawled across the planet trying to make the same distance in a full day.

At this point in my log I made a remark about Francis Chichester. To be honest I’ve never been a lover of your conventional hero. My type is like Rome’s sister, Terry, who had a cancerous breast removed just before I sailed. That did not stop her walking down to Solitaire or laughing at the party. During the Second World War I wanted to be a pilot and envied those I saw walking the streets, wings on their breasts, popsies on their arms – the Few who saved the country. But the real heroes for me were the poor devils who spent year after year in mud, covered in lice, until one day some idiot told them to stick their heads up and get them blown off. They received no medals, were never called ‘heroes’ but only because they were not of the few, but the many. Bloody millions of them.

Chichester, Robin Knox-Johnston, Alex Rose were people I admired for living full lives. Apart from Slocum I had read only one of their books but because I found Chichester’s Gypsy Moth Circles The World among my paperbacks, I read it to check my positions and times for different stages of the voyage against his. In the ship’s log that day I noted that it had taken Chichester only 22 days to reach my position against Solitaire’s 32. No way could Solitaire equal Gypsy Moth’s times. We would set no records; our satisfaction would come from finishing something we had started.

Solitaire continued south through confused seas and grey, overcast skies, tacking back and forth, dropping off the top of waves, decks awash. Concerned half the time because we carried so little sail, worried the next because of sea falling from under us, an anxious eye on the weakened, straining rigging.

For a few days the sun sulked behind heavy layers of mist and clouds, the odd smile it managed so fleeting that it could have been imagined. Dead reckoning put us 300 miles above the equator. Since leaving England I had used one chart only to cover the 3,500 miles we had logged, one of the luxuries I had indulged in! It would have been safer to have had charts of the islands we passed, but a chart of even a harbour will cost as much as one covering several thousand miles. Chart two would have brought looks of disbelief from any self-respecting yachtsman. While in Darwin, Australia, I had photocopied one of Terrell’s charts covering the Atlantic from 10°N to 37°S, say 2,820 miles. It was in two pieces as it was too large for the machine in one go and made of thin, coffee-stained, pencil-marked paper. Alas, it did not even cover the 200 miles below the Cape of Good Hope, which I needed to help avoid the fast-flowing Agulhas Current that sweeps from east to west under South Africa. The lack of food, equipment, sails and charts I had accepted before starting out. My log complained constantly about this, but it was only my way of letting off steam.

In the heavy seas, Solitaire had started taking on water from the forward compartment and I needed to pump out her bilges twice a day. Once through the doldrums, with their squalls and confused seas, things would improve, but I felt useless as I watched the boat try so hard for so little progress, one working her heart out while the other sat around long-faced and complaining. That apart, my health was good. I still worried about small things like appendicitis, breaking a leg or simply needing a heart transplant. That’s another thing I find amusing, being asked if it would not be safer to have two aboard for such emergencies. In fact all you do is double the chances of trouble.

The end of our fifth week found us 296 miles above the Equator, 18°24´W. We had just finished one long tack to the east. Our next would take us back to around 20°W. That week we logged 632 miles which sounds pretty fair until you look at the chart and find that all you have made good in the last 24 hours is 90 miles due east when you want to be sailing south! After 35 days we had travelled 3,615 miles, still holding onto our 100 miles a day, but only just.

In week six more living things, sea birds, started to join us, this time brown in colour. They needed constant winds for survival; perhaps, soon, we would be out of the doldrums, I thought. I was fitter than I had been for two years and my spare tyre had been worn away by Solitaire’s constant movement. My skin had toughened so that I no longer worried about sunburn, and I had settled to my planned diet, baking bread every third day to accompany the eggs and onions. I was conscientiously leaving the food that would last until the end of the voyage.

The biggest lift to my spirits was that soon we would cross the Equator and have Ascension Island within easy reach, and Rome and Annegret’s first parcel to open. I started to look forward to that day with an enthusiasm I had not experienced since I was a small boy. My log became full of the event. On Monday, August 18th, our noon sight showed us to be just 24 miles north of the Equator. I could have cheated and opened my present then, arguing that with luck we would cross over the line before midnight. However, I had promised myself that no present would be opened until the specified time. Nevertheless it slept with me at the bottom of my bunk. We crossed the line at 10pm GMT. Inside the parcel was a lovely tin of ham, enough for two meals, a tin of fruit, another of coleslaw, a can of beer, chocolates, sweets and a letter from Annegret. My log read:

Just opened my parcel. Over the moon with contents. I’ve been cutting down on eating my tinned food but tonight a special treat of cooked ham and coleslaw. I’ll be drinking to Rome’s and Annegret’s health with the beer they supplied. Makes me remember the many times they’ve had me round to dinner. God bless them! Have taken pictures of parcel with Rome’s camera.

Rome had lent me his, together with three rolls of 35mm film. Then Peter Tolputt had turned up with another easy-to-use camera and more film. It was one of the things I just had not even considered because of the cost. Later I was to be pleased that my friends had.

At the end of our sixth week we were 4,155 miles out from Lymington (the direct route by chart was more like 3,800). That week we had logged 540 miles, but by direct line, Wednesday to Wednesday, noon to noon, only 440 miles. Despite the lost 100 miles there was much to be grateful for: the winds had settled from the south-east and were allowing Solitaire to sail close to them on a southerly heading. During the day I saw my first whales of the voyage, brown monsters that broke the surface half-a-mile away, blowing water vapour, disappearing, reappearing, bothering no one. That day’s log finished on a cheerful note, ‘Now for fresh bread, the last of yesterday’s ham, fresh onion and soup. Blue sky, scattered white clouds, winds south-east. A good book. It can’t be bad.’

August 22nd. For the first time in nine days we covered 100 miles in the right direction. Looking at the chart and reading the daily logged distance you would have thought the rest of the seventh week was sailed in the same blissful conditions: our pencilled course flew arrow-straight for 602 miles, never wavering from our intended longitude of 22°W. The noon positions were equally spaced, 86 miles, 81, 87, 87, 85, 77 miles. Only on reading the log do you realise how bad the conditions were. Solitaire has sailed in far worse seas – in fact the winds barely blew over Force 8 (39mph). Maybe it was just worry over the gear and the distance still to go, but I have never known my nerves so raw. For the first time I began to wonder what the devil I was doing out here.

It started that Thursday night with the entry, ‘Could be past Ascension Island in a few days if sails, gear and guardian angel don’t let us down. Winds gusting, Solitaire dropping off the odd wave.’

Friday. Changed down to working jib during the night, winds gusting Force 6. Lots of square waves give impression of climbing upstairs. Can’t increase sail area because of slamming. All to be expected in this area with its high swells. Still managing to head south (slowly), blue sky, scattered clouds, 86 miles in 24 hours.

Saturday. No sights possible, very rough sea. 81 miles in 24 hours. Still working jib and one reef in mainsail. Charts show Force 4 winds from south-east. Holding approximate course south, but sea throwing Solitaire all over the ocean. One minute becalmed, next screaming winds. Bilges constantly filling. Very little sleep with all the bouncing. Nerves get on edge when Solitaire is knocked about. Nothing I can do: if I reduce sail further we won’t make any headway.

Sunday. Solitaire still being thrown about in high angry seas. Very high winds during night with impressive waves. Double-reefed main. Little sleep, moments of fear. Worrying to have Solitaire drop from the top of high waves. What will the Southern Ocean bring?

Monday. Pram cover over main hatchway broken (can be fixed later). Only making 80 to 90 miles a day. I can’t push Solitaire harder in these conditions. Panic this morning: one clock was five minutes adrift, the other had stopped. This shaking can’t be doing them any good. Changed batteries just to be on the safe side and wrapped them in foam. Thank goodness for the portable radio: at least I can get time checks and reset the clocks. Bilges full of water again. Have not been eating well. Impossible to go in cockpit with these breaking seas. No room to move about below with water containers covering the cabin floor. I spend hours grasping the chart table and looking astern. Solitaire feels as if she is smashing through doors without a chance to run at them, a steeplechaser with obstacles too close together. Not being given time to recover from one jump before finding the next racing towards her. It’s just bash, bash, bash with no chance to build up speed. Suddenly to find herself plunging down into pits being brought up short with shattering jerks. The sea is shaking with mirth at our confusion. Mast and rigging alternatively slacken and stiffen.

Tuesday. High wind squalls started at 0300. Seas high and angry, double-reefed and working jib. Not my idea of sailing, one of the times I’d rather be watching TV. It’s three weeks since we had a good day’s sail. Anyone who thinks this is pleasant is mad, mad, mad.

Wednesday, August 27th. Noon and the end of the worst week at sea for a long time. During the week we passed 500 miles west of Ascension Island. It was while moored to a landing barge in 1978 that I’d been scared by some of the biggest swells in the world. The pilot book puts them at more than 30ft. I’m confident the seas are due to similar abnormal conditions. To find such conditions in an area that the chart suggest were reasonable does not augur well for the areas shown as bad! It’s difficult to work on deck and gazing over the stern from the cabin for hours hardly helps. Reading makes the time fly and helps shut out unpalatable thoughts, and it’s warm.

When I was not frightening myself looking down at breaking seas I would sit on my bunk with a book or sort out the mysteries of the NATO food parcels. I found some plain chocolate that went down well and suddenly became aware that I was the proud owner of ten tin openers!

The eighth week at sea was a week of contrasts. The southeast winds from the Cape of Good Hope would soon start in a clockwise direction, veering first to south, then south-west, finally becoming the Roaring Forties 1,500 miles to the south. While they made up their minds what to do they swung back and forth, giving beautiful tropical days with time to sort out leaks and damage. I repaired the pram cover and the forward escape hatch, putting a beam underneath it and securing that to its hinges to ensure it would not fly open in a capsize. Anchor and chain were stored in the stern locker, which also contained the exhaust outlet. Were the anchors to smash the exhaust seacock the sea would flood in faster than I could pump it out so I brought the anchor below and secured it under a bunk. Sorted and repacked our supplies, doing everything I could to prepare us for the storms ahead. The end of the week came with one of the trip’s biggest surprises.

I was on my bunk with nose stuck in a book, enjoying one of the better days and thinking I might wander on deck for a noon sight, when I heard the most horrible sound as if we were in the middle of a herd of groaning, pregnant elephants. Ye gods, I thought, the nearest elephant should be 2,000 miles away. I threw the book to one side and dashed on deck to find a few 20-ton whales making improper advances. We were in the middle of a school of these magnificent creatures, some so close that I could have jumped on their backs for a free ride. I rushed below for a camera and managed a couple of shots as they departed.

In the eighth week we logged 627 miles, 5,384 miles in 56 days. We had fallen below our 100 miles a day. The Cape of Good Hope lay ESE, 2,220 miles away. The ninth week started well when the winds went round to the north-east. For the first time in weeks we had a free wind blowing at three to four and came onto a broad reach with the poor old number two genoa and a full main. We glided along without the old smashing and banging. Then the sheet broke and the genoa flew free. However, I soon had it repaired and we continued on lazily. Further south, a shirt joined the shorts I had been wearing during the day. At night I no longer lay on top of my sleeping bag but climbed inside for warmth.

On September 9th we celebrated two full calendar months at sea. Back home they would be making ready for an English winter while we sailed into a South African spring. I became more of a crew than skipper, following quietly whispered commands as I soothed Solitaire’s occasional displeasures, taking the strain from her weak body. ‘I’m hard pressed,’ she would complain and I would reduce sail. ‘You’re driving me too hard.’ I would ease the self-steering so she could take the waves on her quarter.

The ship’s log grew repetitive: grey sky – grey sea – grey skipper. Breaking into choppy seas, I really am sick, sick, sick of it. But repetition breeds over-confidence and stupidity. Returning from changing a headsail one stormy night I put the kettle on for tea and reached down to remove my safety harness – it wasn’t there!

At the end of our ninth week at sea we recorded a distance of 776 miles, but the tenth was far worse, with only 646 miles to show for it. I’m sure the slow progress was mainly my own fault, although the pilot charts did not help too much. Tristan da Cunha now lay 550 miles south of us. The South African high-pressure area with the light winds and calms was still to port. Solitaire had started to sweep in a gentle curve to the south-east to pass well under the Cape of Good Hope.

It’s a mistake that many people make in life: you see your target and head straight for it. I should have used my golfing experience and made a dog’s leg of it, heading further south towards Tristan, perhaps entering the Roaring Forties before turning south and making for Australia. If it was a mistake to take the direct route it was one I could live with. Many better-qualified yachtsmen had made the same mistake in this area. The pilot charts proved unreliable: instead of skirting the high-pressure area we must have sailed into its outer fringes of calms. Well, as Gracie Fields used to sing, every cloud has its silver lining. The silver in our present cloud was that the calms allowed us to do more work sorting things out.

During my tenth week at sea I started to use words in the ship’s log that would have been unusual on our first round-the-world voyage – ‘nerves’ and ‘depression’:

Engine: Run for one hour, diesel and water containers stowed.

Food and water: Should have enough food to reach New Zealand, a quarter of water used.

Temperature: Now 70°F (90° on the equator), so am wearing sweater in early mornings, and really need sleeping bag at night.

Antifouling: A few goose barnacles, seems to be working well.

Solitaire: In better shape than when she left England apart from number two genoa.

Crew: Has moments of deep depression, worrying about Solitaire’s gear and sailing under jury-rig. Although Cape Town is 1,500 miles away and hoped to make it in 70 days, so far we have been lucky and I have no reason to complain of our progress. So why do I feel so depressed?

The end of her tenth week brought new records for Solitaire: on her first voyage her longest time at sea had been 69 days, the greatest distance travelled around 6,000 miles. These had now increased to 70 days and 6,614 miles; not an earth-shattering achievement, but for the speck moving across the oceans it was important. We were sailing into the unknown with new problems that would have to be overcome. Somehow Solitaire had to survive the gales of the Southern Ocean, somehow round Cape Horn. If at that stage I had been asked my main concern I would have answered that it was my own part in the voyage, not Solitaire’s. The urge to round Cape Horn was as strong as ever and nothing would stop me, but I could not understand my mental condition. Unless I could sort myself out I was likely to end the voyage in some form of mental straitjacket.

A long-distance sailor on his own must be many things: captain, cook, navigator and doctor but, most important of all, he must be able to understand himself and recognise his own limitations, mental and physical. It sounds easy, but people living ashore pay psychiatrists thousands of pounds a year to understand themselves, despite having family and friends with whom to discuss their problems. Solitaire and I were cut off from the outside world. We had no transmitter with which to make the odd call, ‘I say, old boy, I wonder if you could help me? I’m in the middle of the Pacific Ocean and I’ve gone off my rocker.’

When I left England everything seemed so straightforward. I would sail around the world for my own satisfaction and would survive for my own love of life, the desire to see family, friends and England again. To make the voyage I would be prepared for tiredness, cold, hunger and long periods of fear. On my first voyage I had been frightened only for short periods, mostly during the Brazilian episode. I believed I could stand this type of fear for five months or so but I felt it would not attack me until I reached the Southern Ocean. But after crossing the Equator and beating into seas that normally would have given little concern I became frightened, my nerves rubbed raw for no apparent reason. At one stage I thought I knew why: some of Chichester’s descriptions of the conditions I could expect were so vivid that I put down the book vowing not to read it again until we were safely home.

Solitaire’s rigging might not survive a capsize, but all who had made this voyage had suffered at least one. What then?

I bitterly resented my lost year thanks to the sail manufacturer and the unjust outcome of the court case. That I felt so apprehensive so early in the voyage proved that, at heart, I was not brave. At sea I would turn anything I could to my advantage, not an unusual trait. It’s surprising how after spending their lives without a God, many become aware of Him when in need. I used friends: ‘What would Rome or Rex do in this situation?’ Others had survived, why shouldn’t I? Ah, well, time would tell.

Each day brought danger nearer. In the eleventh week we logged 470 miles, six more than the previous week, in the same old mixture of calms and gales. The worst started on Friday, September 19th, when we ran with screaming winds, under working jib only while rogue breaking waves slammed into Solitaire ripping one of the heavy canvas spray dodgers in half. What worried me was that I was over-reacting to conditions we had been through a dozen times before. On my first voyage I had been unconcerned, indeed would have listened to the wave’s onrush with interest, putting aside my book for a few moments to hold onto the bunk, awaited the impact, then continue reading. If I was reacting in comparatively safe conditions, how would I cope with real danger when it came?

I spent two days repairing the torn dodger. On September 22nd I recorded our longitude as 00°15´E, in other words we were 15 miles east of Greenwich. Once past that date line the working of our navigation would alter. And September 23rd was the anniversary of my Brazilian adventure when I had started to think about a second voyage around the world. This time I would make the correct adjustments when using navigation figures. As yet I had no desire to contemplate a third voyage!

By the end of our eleventh week we had sailed 7,084 miles. As I reported in the log:

We had rode one gale during the week and were becalmed for its last 12 hours. New Zealand will take forever at this rate. Plenty of sea birds about from small petrels to aircraft-sized albatrosses. Visits from my dolphins after staying away for two weeks. Nice to have my friends back. I have been photographing my fellow travellers with Rome’s camera. Still managing to read a good deal. Thank goodness I enjoy books so much. Long days in these conditions would seem endless if you could not lose yourself in other times and places. I’m reading one of Annegret’s books called Hawaii by James A Michener. Have hardly put it down for three days. Antifouling still working well apart from barnacles on the rudder, propeller and a few on the topsides. More than satisfied.

The twelfth week started with Cape Town 720 miles to the east, a good week’s sail to safety, steaks, hot baths and warm beds. We could be tempted only under jury-rig. Once past Cape Agulhas I could open Rome’s second parcel. I planned to round the Cape 300 miles south of Africa for two reasons: to keep well below the west-flowing 5-knot Agulhas Current, and to avoid the 90 fathoms continental shelf. The seas, 12,000 deep beyond the shelf, would be kinder. The problem in sailing so low was that my charts ran out at 37°S. I covered the extra 180 miles by sticking an odd piece of paper to the chart and pencilling the lines of longitude and latitude onto that. Solitaire was about to round her first objective on a scrap of writing paper.

The week was wet and miserable, navigation made difficult by heavy rain clouds. The winds played tricks. Were the pilot charts chuckling quietly, having suggested winds from the north to southwest Force 5 to 6? Any of these would have been acceptable but Solitaire had to battle against winds on her nose – from the south. The odd day we had stern winds brought our first thick fog. At least we knew that no other ship would be within a couple of hundred miles of us, ghosts of lost square riggers excepted, for only a pig-headed fool would venture so far south.

It was fitting that the thirteenth week should be the worst I had ever spent at sea, the week I thought I had lost Solitaire, the week that I lost my affection for England. Since leaving home I had been bitter, frightened and depressed. The bitterness I could understand but not the time I was taking to get over it. The court case had upset me deeply. Weren’t the upper classes, the lords of the manor, supposed to look after the peasants? I could picture Solitaire beating up the English Channel, her red ensign streaming in the wind, with a certain pride in completing the long haul. But after 90 days at sea the picture had started to fade.

And this was the day the storm started.