South Atlantic – Indian Ocean

September – October 1980

Thursday, September 30th. Our noon sight showed we were about to enter the Roaring Forties, 250 miles below South Africa on latitude 39°S. The morning winds, around Force 4, came from the north and were cold despite my heavy sweater, foul weather gear and sea boots. It was not just the cold that had made me put on the full gear: the day before one of the water containers had burst and soaked both my sleeping bags so that the only way I could sleep on them now was by wearing oilskins.

I had been forced to stop using the old number two genoa a week before as we had been getting the odd gust that would have ripped it in half. We were reaching under working jib and main with one reef, which had gone in when I had started to feel uneasy. Although, cold apart, it seemed a perfect sailing day with a few scattered clouds in an otherwise clear winter sky. A swell started to build up and the hairs at the base of my neck began to stand on end. During the afternoon wind strength remained constant but the sky turned from blue to black in less than two hours as though coats of film, one atop the other, had finally turned sea and sky to jet. There were no breaking waves but the swell increased until the sea rollercoastered.

Normally I would have taken down the main but for weeks I had been over-reacting. Was I at it again? The only headsail strong enough for these waters was the working jib, which meant I would have to keep the main up for as long as possible or the voyage would last for ever. Apart from running out of food we would be too late this year to round Cape Horn safely.

If we were to have any chance of maintaining schedule the old rules of the game would have to go by the board, starting with the first and oldest: reef or reduce sails as soon as you think about it. That afternoon I was trying to read Hawaii, so uneasily that I found I was scanning the same line again and again. Although Solitaire carried no wind speed indicator I know that during our first voyage outside Cape Town we survived winds in excess of 100 miles an hour (as later reported by ships damaged in the area). I know what they sound like in the rigging, what effect flying spray has on bare flesh. This storm did not frighten me as it lasted only a few hours and the waves had little time to build up. My main fear was being run down by a tanker.

When the storm struck – without warning – it was with the force of one of these tankers. This was an assassin’s bullet hitting before the victim heard the sound of the rifle. You’re alive, you’re dead, you’re upright, you’re on your side. There’s a whisper in the rigging, then it screams. A panic-stricken dash to the deck to find the mast nearly in the water. Both spray dodgers have gone. The self-steering wind vane is pushed fully over and is vibrating against its stop. Sails are filling with the sea, their seams about to split. Both sheets are released; for a moment part of the boom and main disappear over the side and God knows what’s happening to the headsail because I’m blinded by wind and spray.

I clawed my way to the mast and tugged on the main’s luff but the bloody thing would not come down. The pressure on the sail was jamming the slides. Finally I succeeded in lowering it. I should have returned to the cockpit and pulled back the boom inside Solitaire’s guard-rails but if I didn’t do something about the headsail I’d lose it. Quickly I lashed part of the main to the boom, nothing below me but white broken water. Once the jib was safely down I could return to the cockpit and retrieve the boom dangling in the sea. I tied a rope onto the wind vane and around my waist. When I released it from the self-steering unit it tried to take off like a rocket, bearing me with it. I promptly had second thoughts and in the end managed to take it below, where I wrapped it in a protective blanket.

Now I could think about my own needs. Luckily I had been wearing my wet weather gear on deck, the first time I had ever sat around with sea boots on. As I like to feel Solitaire moving under my bare feet, wearing sea boots is like going to bed with a woman wearing boxing gloves. I had had no time to put a towel around my neck so my shirt and sweater were saturated and as I realised this my teeth began to chatter. Then the risks I had taken without a safety harness dawned on me and the chattering increased in tempo.

Tea would have tasted like ambrosia, but first I had to fit a shock-cord onto the self-steering rudder to prevent it banging back and forth, and I needed to retrieve the 30ft of line on the log. One spray dodger was again ripped in half, the other hung over the side, held by a few odd ties. Both had to be removed and stowed. At that stage I was merely thinking of just another stormy night at sea. I would put extra lashings on the sails and rubber dinghy, pump out the bilges, then settle down for a night’s sleep lying a-hull.

When the storm started I was confident that Solitaire and I had all the answers. After all, hadn’t we faced every situation, every type of wind, every type of sea? All sails were down. It would be hours before the seas built up and became dangerous. Lord, what poor misguided fools we are!

Without knowing it, everything I had done so far had been wrong. I was working to rules from the first voyage, rules which said that, provided everything was secured and there was a good depth of water, storms were nothing to worry about. There had been exceptions of course, when the storm brought fierce lightning, which I hated, or we lay off a lee shore or in a shipping lane. Then I would prefer to be sitting in front of a roaring fire, a dog at my feet, contemplating a stroll to the local for a pint with the lads. The rules from our first voyage were as outdated as trying to fight an atomic war with conkers.

I was starting to suspect even the preparation for the voyage. Money, or its shortage, decided what we could or could not take with us, apart from my wet weather gear, which was the best I could find, being the type used by Rome on his Whitbread round-the-world voyage. It seemed to have everything I wanted: the jacket heavily quilted for warmth; the double-lined trousers had substantial plastic zips, which in turn were protected by flaps. The trouser tops fitted snugly under armpits and the jacket had a built-in harness on to which the safety line clipped. The outfit cost around £150, it was money well spent. The first problem showed up when I tried to wear sea boots, which I normally don only when close to English waters. Even at night, although my feet would be cold, I felt no pain and certainly had no frostbite worries. In the old days in emergencies I would dash on deck naked apart from the safety harness. Now when I was needed there in a hurry, I first had to tuck my long trousers into my socks, pull on the outer trousers, put on sea boots, then work the trousers back over the boots, tightening the tapes. The linings slowed down the drill.

I hit another snag trying to get back on deck – I could not get through the hatch! In storms I would lock myself below and wait for a lull, then slide back the hatch cover, remove the top board, step out and replace them. It was fairly easy provided you were not wearing padded jackets. After leaving England I had fitted two bolts to the top board to prevent its loss during a capsize. To clip on my safety line I had to lean over the boards to reach the U-bolt. It made me feel sick. Solitaire’s movements were so violent and the winds so strong that I had to keep my back to them. So powerful was the spray that I feared for my sight.

It had become very dark and I was becoming painfully aware that my feet were turning to ice. There was more than a foot of water in the cockpit. With the spray-dodgers lost, seawater broke over us more quickly than we could jettison. It forced its way up my wet suit and over the top of my boots, freezing my legs and feet.

Somehow the trailing long line, with its weight and spinners, had wrapped itself around the self-steering gear, and as it was nearest I decided to make a start with this. Waves continued to break over us and an aching body joined my frozen feet. For the first time my body temperature worried me. In winter’s seas you might be lucky to last half-an-hour if you fell overboard off the English coast but if I went over in these latitudes I would have only minutes.

For the first time I realised that many of Solitaire’s features that had worked perfectly on the shake-down cruise were a disadvantage in these seas. The skirt that ran around the top of the cockpit, 3–9in above the deck, had prevented water streaming into the cockpit. Now it also trapped and held it until Solitaire was thrown on her side and the seawater partly spilled out. The cockpit that had been perfect in Tahiti, Australia, and South Africa was far too large. Instead of holding parties of ten or twelve happy guests it was now holding tons of freezing seawater. The cockpit was made from a single moulding with a 14in seat halfway down its side dropping to the cockpit floor. The seats lifted to provide locker space. I had modified the two lockers so that the channels around their covers were self-draining. On the first voyage the covers were held in place only by shock cords since I could not afford anything more expensive. I had attached half-inch ropes onto the hull, fed them through holes in the locker tops and secured them in this Mickey Mouse fashion. When leaving the cabin you stepped onto a centre shelf which held the mainsheet traveller. An adjustable pulley and block ran from the traveller to the end of the boom, holding the latter in place.

The main trouble with leaving the cabin was my heavy clothing coupled with Solitaire’s violent pitching and tossing. What I really needed was something to hold onto and use as a lever. The pram cover frame was far too weak to suffice.

I centred the mainsheet traveller, which meant that the ropes to the foot of the boom passed in front of the hatch, giving me room to squeeze by, using them as a handhold. All I wanted now was to strip off my wet clothes and brew tea, but once I had struggled below I remembered I still had to pump out the bilges. So back I went out into the cold, the breaking seas and the howling winds. Then came the bliss of holding the kettle on top of a dancing stove to produce a life-giving, hot, sweet cuppa. When I started to think about changing my wet clothes I realised I had insufficient replacements and those I had were the wrong type for these conditions.

The suitcase I had carried around the world in 1968 now contained one suit, a dozen assorted nylon dress shirts and sports shirts, and five sweaters. Rex Wardman had also given me a lovely thermal jacket for Christmas, and Margaret a pair of quilted trousers. She had driven me to the Surplus Army and Navy stores in Southampton, where they were selling off old ex-navy diving suits for £10. Unfortunately when we arrived they had sold out apart from one moth-eaten suit that was falling to bits. It was a green fur-lined one-piece affair that I tried on and spent an enjoyable half-hour running around like the Incredible Hulk, frightening customers.

On the way back to Lymington I had asked Margaret if I could put it on again and lean out of the car window. At the time we were driving through the Southampton Red Light district.

‘You do and I’ll throw you out,’ was Margaret’s reply.

The thought of a green man knocking on doors in that area had me chuckling for days. Funny how the mind wanders when you are cold and tired!

In a storm like that we could be badly damaged at any time so I had to keep my wet weather gear on. Even if I changed my sweater it would be dry only for a few minutes before soaking up the water from my jacket. The best I could do was take off my boots, empty them, and wring out my socks. After that I wedged myself on the floor behind the water containers and pulled a sleeping bag over my head to retain some body heat. At first it was too cold to sleep but, as my clothes reached body temperature, I started to drop off – only to be brought back with a shock to find myself sitting in 2in of water covering the cabin floor. The bilges were full again despite my pumping them dry within the last two hours. We must have taken in well over 100 gallons in that time.

I waited for Solitaire to steady herself, slid back the hatch cover and put my head out into a shrieking, screaming world of horror. Massive seas were crashing on my poor boat, trying to bury her alive, giving her no chance to recover, to fight back. The cockpit was full of water. The lockers that I had made self-draining for the odd breaker were under boiling seas that would be gushing under their covers and running forward under the engine mounts to fill the bilges and then, more slowly, the cabin itself.

Given any other choice I would have gladly taken it. Instead I picked up the bilge pump handle and pushed through the hatchway. Timing it wrongly, I dropped up to my waist in freezing water. My boots filled and the seas worked up inside my legs. Solitaire rolled and half the water left the cockpit. I banged my face on a winch and started pumping. Mom and Dad would be warm in bed now, I thought. God, I’d love to see them! I kept on pumping. Sometimes I thought I had nearly finished only to have another wave break over us. For all I knew the cabin could now be completely filled with water, the driest place in the boat precisely where I stood. If we were sinking, how long would it take to reach the seabed, 2 miles down? The water grew denser the deeper you went. There were aquatic creatures down there without eyes – would they turn as we slipped past? Solitaire’s white shimmering shape, a lonely figure dressed in red still attached by lifeline. How long would it take? Hours? Weeks? Would Solitaire blame me for letting her down? Was being tied to your mistakes for eternity a definition of hell?

Once the bilges are dry the pump passes air only and the handle needs little pressure to move it. When I believed I could be no colder, that I could no longer keep my eyes open for another second, the pump started sucking air. I staggered below, took off my boots, wrapped a towel round my feet and boiled a cup of tea, warming my hands over the flame. After squeezing the water out of my socks I put on my boots again, longing for sleep and sank onto the floor behind the water containers – where I found myself in deep water. Two minutes later I was back in the cockpit, pumping.

The night lasted a millennium. Each time I thought I could close my eyes more freezing water streamed through the cabin floor. The seas were replacing the blood that ran in my veins, the heart pumping ice water to the brain faster than I could jettison it over Solitaire’s side. It was numbing, stupefying. At times I was unaware whether I was the bent body in the cockpit or the huddled shape on the cabin floor. At last the sky lightened with dawn. After so long in a black, screaming hell, eyes blinded by stinging salt water, I would see again.

I slid back the hatch cover and for a moment wished I had remained blind. This could be no storm, for storms had waves, the stronger the winds the faster the waves, the higher they reached. Waves marched majestically across oceans like regiments of soldiers. But this was no ocean, just a shrieking horror of unmoving mountains reaching up to a black sky. Suddenly in the distance a flock of small grey birds with outstretched wings tried to scramble up the lower slopes, like so many little old ladies with raised skirts splashing through puddles. As we dropped deeper into the valley the howling wind seemed to slacken and Solitaire settled onto the sea’s green floor. Over there was the perfect setting for a thatched cottage.

The real nightmare was that despite the deafening sound nothing moved. Then the top of a mountain turned white as though covered with snow and an avalanche descended, slowly at first, very slowly, then gathering speed, roaring down on us, trying to kill its trespassers. I slammed the hatch shut, expecting Solitaire to be rolled over and over like a puppy at play. When the avalanche reached us there was not the crash I had expected. Instead the sea flowed over us, carrying us sideways for a few hundred yards before it released its grip and promptly ignored us, a matchstick in its path. For a moment Solitaire staggered upright in its wake and again I opened the hatch. The air was filled with stinging sleet. Solitaire lay buried in the snow, her outline marked only by the stanchions that stood up like sticks on a cold winter’s day. Solitaire rolled, spilling half the water over her side.

Surely nothing could live in this mad world. Waves would kill us without noticing. Somehow I had to get the boat moving to give her a fighting chance. The first thing was to replace the self-steering wind vane consisting of nylon stretched over aluminium frame, no more than 3ft long. But the screaming wind tried to tear it from me and it was a fight just to hold it. There was no way I could get it working.

I considered putting up a small headsail to try steering myself. But if I was at the helm I would be unable to pump. Even if I managed both, the winds were still from the north so I would have to run south. And land to the north was more than 300 miles away. If I lost the mast it could take weeks to reach land under jury-rig and any attempt to round Cape Horn would have to be put off for a further year.

Suddenly I was aware of something I had been putting off all night. I had to use the lavatory – or rather the bucket, for the lavatory was out of the question since I’d have been thrown around like a pea in a tin whistle. But the bucket and chuck-it method was far too risky. Then I thought of an idea that was to serve me well for the rest of the voyage. Plastic bin liners were the answer. In order not to foul the bucket I used one of these, putting a couple of sheets of newspaper in the bottom for added strength. After sealing the bag I waited my chance and threw it into outer space, assisted by a wind blowing at more than 100 miles an hour. I believe it was the first time this type of payload had been put into orbit.

It was time to look after Solitaire again. I went back into the pumping routine, removing boots and socks, a cup of tea, then more pumping. During one of these periods in the flooded cockpit something happened that I would have given anything to reverse. Time seemed to slow. Whether it was the contrast between the howling winds and the stationary mountains I don’t know. At times the illusion was so complete that I felt I could step off Solitaire, leaving her freezing cockpit, and run down the green valleys, exploring their secrets. The only thing that stopped me was the knowledge that she would not be there awaiting me when I returned.

Another sequence of thoughts started after another wave hit us without the following swell that would have rolled Solitaire, partly emptying her. I found myself repeating, ‘There was no need for this, no bloody need at all.’ A week before leaving England a friend had given me a new bilge pump, which sat in one of the lockers because I had been unable to afford the piping with which to fit it in the cabin. Had it been installed I need never have stepped outside; my clothes would have remained reasonably warm and I would not be standing in misery, tormented by sodden clothes, cold, tired, battered and bruised.

I started to understand the bitterness I’d felt since leaving England, a country I had loved as long as I could remember, when to hear a choir singing Land of Hope and Glory would cause tears to spring to my eyes. I’m not sure when I started to lose this feeling for my native land. Perhaps it was the court case. Perhaps it was after watching an Englishman run for his country and collect a contract to sell a product on TV he had never used. Perhaps it was just that I’d grown old, seen too many lands, met so many friendly people. Whatever the reason, the loss was mine and Solitaire’s. I regretted it, but the rest of the voyage would be made without the help of patriotic choirs.

At three o’clock on this day we had been storm-wracked for 24 hours. I had been unable to sleep during that time, I was soaking wet, had swallowed a gallon of tea but had eaten nothing. In the past I had survived much longer without food or sleep, but my main worry was the cold, as I had no previous experience to fall back on. There was no point in putting on warm clothing when once in the cockpit I would be as wet as ever. I thought about leaving the stove turned on. We had three 32lb-bottles of gas on board, and, as on the last voyage, I had used only one bottle every six months. So there was some to spare but essentially I wanted to keep the extra gas for rounding Cape Horn. In any case nearly all my time was spent outside the cabin.

After discovering that I could not replace the self-steering vane I started to consider how to live in the Southern Ocean by correcting my mistakes. I should not have tried lying abeam to these seas or removing the self-steering wind vane. I knew I must always keep up enough sail to control our position to the waves. I could have done little with the self-steering gear at the time as the vane was much too big for the wind strength, which demanded smaller, stronger vanes. I had three plywood vanes from the first voyage, which were unusable in their present state. The blade-holder supported only about 4in at the bottom of the vane and pressure had to be distributed, so I cannibalised one to supply feathering pieces for the other two vanes and finished just before dark.

Meanwhile the winds were still coming from the north at hurricane strength. I could only sail south, deeper into the Roaring Forties. All I could think of was getting into the Indian Ocean past the Cape of Good Hope. Once there we would be less restricted and could ease our way out of these howling, desolate seas. With luck we would find warmer weather and give ourselves a chance to dry out and renew our strength for future battles.

I spent another miserable night praying for the winds to abate. If my guardian angel could not arrange that could he please swing them to the west, giving Solitaire wings to leave these watery mountains? No craft could continue to take such punishment and I felt like the condemned man waiting for the trap to spring. As I watched the sea break on us I could see the hangman reaching for the lever. Again we were lifted and carried effortlessly on a boiling cloud, and then, after a few hundred yards, released as a cat plays with a mouse. Sometimes I was permitted to pump Solitaire dry before it sprang again, sometimes I was halfway through the hatch dreaming of wrapping my hands around a hot cup and rubbing the circulation back into cold feet when there would be a roar and once again we would be buried.

I was reminded of the Germans outside Stalingrad during the Second World War. Ill-clad in their normal dress uniforms they died in a Russian winter. I remember one upright corpse standing frozen, staring through dead eyes. Someone had stretched out his arm and pointed a finger, turning him into a road sign. At least it seemed a useful way to end your life. When I stood in freezing water up to my waist, unable to move my arms or open my eyes, I wondered if my last effort should be to point to Cape Horn as a service to following seamen. Instead I kept pumping.

Dawn came and somehow we struggled through another day. In fact it went better than the first. Although the storm had not abated I felt it could get no worse and as we had survived one day, why not this one? The cat and mouse game the sea played with us was wearing a bit thin. It was not the dying I feared or even the method. I would rather drown than lie for years, suffering without hope, watching my family and friends walk past a shell for which I had no further use, hearing a priest quote from a book as unreliable as yesterday’s newspapers. Yet there is some supernatural force, for without it Solitaire would have started on her journey to the bottom long ago. I had no wish to die. There were many things I wanted to do, horizons still to be scanned. And I wanted to see my family once more, just once more, so I kept on pumping.

During our third night of storm I realised that with the dawn Solitaire would have to take over the responsibility of keeping us alive. In the beginning I had worried that I was not eating. Now nothing mattered but the pumping. Sleep no longer bothered me; sleep was something that happened between life and death. If I closed my eyes now I would die. Dying bothered me but not sleep. All that mattered was the pumping.

With the dawn I would fit a new wind vane and hoist a head-sail. It would make no difference if the winds failed to drop or if they still blew from the north. It was all I could do, my last card. All that mattered was the pumping, but tomorrow I would be able to pump no more. Most of that night I spent in the cockpit, no longer crouching to avoid the breaking seas. Solitaire and I became one, moving in a numb stupor, beaten to our knees. Solitaire staggered defiantly while I worked the pump, readying her for more punishment. My Solitaire had started as an idea in South Africa, something I would use as a common prostitute for my own pleasures, after which I would pass her on to the highest bidder. My love affair with her started on a reef off the Brazilian coast and our courtship had been long and happy. For two days we had celebrated our marriage, a ceremony far more binding than the others I had been party to. In sickness and in health, that was true, but till death us do part, never. We would survive or die together. I would never leave her.

Dawn arrived with no drop in the wind’s strength, the sky still black although I could see over the mountain peaks to the limited horizon. Without their protection the wind screamed in the rigging, a loose halyard vibrating against the mast like a runaway machine gun. In the valleys I fooled myself into thinking the storm was tiring, then Solitaire would rise to the sound of the stuttering gun.

When I had pumped her dry again I started to fit the small plywood vane drilled with an extra hole to take a rope, which I tied round my wrist. I waited my chance and fell into the cockpit with it pressed to my chest. I gripped the pushpit and started to straighten up and for a moment thought I was in a January sale with a mass of bargain-mad housewives tearing at me as though I held the crown jewels. After nearly being swept over the side I managed to rope myself close enough to the self-steering to use both hands to slot in the vane. The blade was adjusted so that its edge faced into wind. The shock cords were taken off its rudder and I freed the locking device. After more than 50 defenceless hours at last we had a means of fighting back.

By this time Solitaire badly needed pumping out again, but bloated by our small victory I decided to haul up a headsail. Both working and storm jibs were already hanked onto the twin forestay. The problem was which was the better to use.

When Solitaire left her home port she had been very much like a five-year-old family car entered for a round-the-world rally. Since sails take the place of a gearbox in a car we could claim she had a five-gear box. First and second gears were new but the third and fourth gears had been used already in one 34,000-mile rally and both were damaged. As Solitaire had no large running sails perhaps you could claim she had no fifth gear. The bolts that held the gearbox in place – the rigging holding the mast – were the wrong type and had been used already on one world trip. And we were about to try to drive out of a land that existed only in a madman’s nightmares. The trouble was the mountains were ice-covered and the screaming winds would try to push the car sideways. Our tyres were bald and we had no brakes. Any car driver would say the answer was simple: at the top of the mountain change into bottom gear to control the descent; at the bottom change into second and drive yourself back into position ready for the next mountain. But even in perfect conditions, with both sails in position, it would take me around ten minutes to make the change. With waves continuously breaking over the decks I would be lucky to hoist a sail in half an hour.

If I used the bigger working jib there was a chance it would rip to pieces on the exposed summits or the rigging, and then the mast would go over the side. If I used the small storm jib there would be no power to control Solitaire in the calmer valleys. I had heard of yachtsmen running under bare poles in storm conditions but had been unable to understand how it was possible in a rough sea. I had heard of running with twin-head storm jibs poled out, but in these conditions it would have been highly dangerous to dive down one of these mountains. At the bottom of the valley the yacht’s bow would dig in and the stern would come over like a pole thrown at the Highland Games. If you came off the dead run and the wind moved from over the stern, one of the running sails would back. Heaven alone knew how long it would take to get sailing again, not to mention possible damage. I decided to use the bigger working headsail. True, it might blow out, I thought, but far better that that happen than be rolled out of control in the troughs.

The 30 minutes I reckoned it would take to hoist the working jib turned into an hour and was completed in an air of misery and bad language. At one interesting stage three waves buried Solitaire one after the other. The position I took up while this was happening was flat across the deck, my hand grasping a safety rope on the side over which the seas were breaking. Both legs had gone through the lines on the other side and were hanging in space. Over the past three days I thought I had experienced every possible way seawater could enter my sea boots. The new method was more complicated and took a little longer, but its route was ingenious. It entered by a hosepipe forced up my sleeve, went over the top of my trousers and down my leg.

After scrambling back to the cockpit I slackened the sheet and hauled up the sail. At first I thought it would tear itself to shreds, but after adjusting the sheets the sail, its seams straining, started to pull Solitaire stern to wind. Then I adjusted the self-steering and main rudder to hold us on a broad reach, the only possible way I can sail Solitaire in such conditions. The main idea is to go down the waves much like a surfboarder, at an angle. The self-steering rudder is not always strong enough to control this type of sailing as the waves take over, trying to push the stern around until the boat lies beam on to the waves. I used the main rudder to control this, its power holding the skid. At the bottom of a run the main rudder helps bring the yacht back onto course ready for the next breaking sea but every manoeuvre has to be just right. Too much correction with the main rudder puts you on the other tack. Usually then the backed sail will tack you again, but the strain on the sails and the forestay sets teeth on edge. Getting it right took frightening minutes whereas normally the time taken is minimal. Of course, Solitaire had never tried to sail down the side of a mountain before.

Things looked up. Seas that had broken over us now pushed us forward in wild breath-taking surges. For minutes we would race in spray and a tumbling mass of white water. Advancing cliffs lifted us like a soaring eagle and we balanced above their snowcapped peaks before plunging down into emerald green fields, often out of control. Solitaire rushed forward, anxious to find peace and lick her wounds.

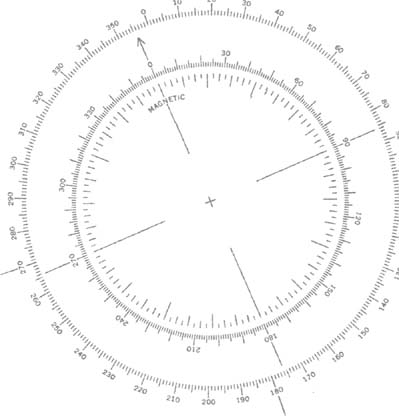

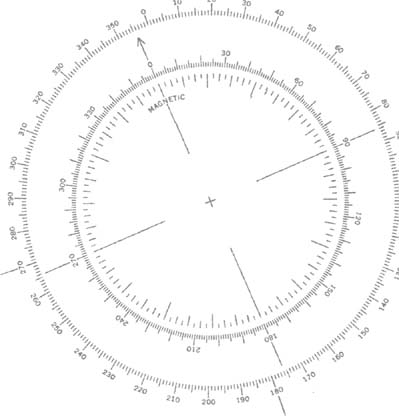

I fitted the trailing log line, which curved in a half circle, the weight and spinner like so many flying fish skipping over the ocean’s surface. The plastic compass was returned to its cockpit holder, our course south-east. The northern winds drove us deeper into the Roaring Forties, but we were clawing our way east, working our way around South Africa and its Cape of Storms. Dead on my feet I went back to pumping the bilges. Over the past three days I had often thought that I was finished, that I could pump no more, that I could no longer survive without sleep. The seconds had turned into minutes, to hours, to days. Now if something went wrong I felt I could still carry on. I just hoped to God I didn’t have to prove it.

When I started this voyage I thought that I could stand being afraid for five weeks and that at the end of that time I would still be sane and able to carry out normal everyday functions. It was a thought based on my past experience. I had not anticipated a situation when for three days I would believe every moment, every breath, could be my last. Oh well, three days gone!

After a while Solitaire settled down to look after us both. A few rogue waves still struck our beam. Now and again we would have 6 or 9in of water on the cockpit floor, but no longer were the seas flooding the lockers. Below, I stripped off every stitch and felt the glory of rubbing myself down with a dry towel, putting on a clean shirt, trousers and sweater and, for a special treat, donned Rex’s thermal jacket. My wet weather gear I turned inside out to drip dry, had a cup of sweet tea and found some chocolate which I ate at the chart table with my head in my arms.

My mother was shaking me. I was 14 years old and it was time to get up, go downstairs and eat my morning porridge, time to put on my overalls and join the bus with half-asleep men, nodding, coughing, grey-faced men moving through their lives like zombies. I did not want to leave my bed to live this nightmare, tried to pull my legs into my chest to squeeze so small I would never be found, but my mother was banging my head. My mother never bangs my head.

I shocked awake, moving through 40 years in a second, exchanging one nightmare for another. Solitaire was in the teeth of a wild beast viciously shaking her from side to side, and she was leaning the wrong way. On this new tack I had slipped sideways. My legs had jammed under the chart table and my head was beating itself to death on the engine cover. When I had freed myself I stood on weak legs, trying to take in through blurred eyes what was happening. I slid back the hatch cover and looked into the face of a breaking wave, slammed the hatch shut and staggered back, only to fall on top of the water containers. From there I heard the wave hit and saw jets of water penetrating the hatch boards.

I threw off my jacket and sweater, for there was no point in getting them wet. It was then that I felt Solitaire start to swing onto her correct heading. Her backed headsail and the self-steering were striving to bring the wind on the right side of her stern while the main rudder that had been set to prevent her skidding and broaching would be working to keep the wind on the wrong side.

For a lifetime she seemed to balance on a knife-edge, rolling from side to side. I watched the breaking seas through her windows, first on one side, then on the other, feeling like a gambler who had bet his last dollar on the turn of a card. If she fell one way I would not have to go on deck but could have a hot meal. If she fell the wrong way I would have to put on wet storm clothes and return to hell.

If Solitaire could correct a backed headsail on her own it would mean I could sleep knowing she would take care of us. I tried to hedge my bet by throwing my weight behind it, bouncing off the starboard side as if I was trying to drive a hole through it. The bet paid off and Solitaire came back on course. The working jib swung across the deck with a shuddering whack whose vibrations ran through us for a full 60 seconds.

It was nearly noon so I must have been asleep for some four hours. I quickly inspected the deck and headsail by holding on to the mainsheet and popping my head around the pram cover. All seemed in order, although the sail looked as if it might rip at any second. The storm jib was still tied securely to the pulpit. The ropes securing the mainsail to the boom were holding.

But the conditions remained terrifying. Any man who claimed that he was unafraid I would have dismissed as a liar. Solitaire still slid down the sides of mountains and at any moment might broach. Once she had rolled on her side at speed she would simply keep rolling. Even if we survived it would be difficult to reach land without a mast. After we had passed South Africa our chances would improve as the motor could then be used to stagger us into port under jury-rig. At the moment if we tried to reach land, the Agulhas Current would sweep us into the South Atlantic.

I was afraid, but that was something I could live with. My fears were less constant than they had been in the past three days, coming and going now like storm clouds. There were even moments of pleasure. Not to be soaked and frozen was a delightful change. There are ways of finding sanity even in a world of horror. You can do normal everyday things, like paying more attention to the trivial than you would at home, despite the fact that your house might turn upside down at any second. Part of this fantasy was the cabin floor carpets. One of life’s pleasures is sinking bare feet into a soft pile carpet when you leave your bed, maybe because as a boy it was always cold boards. Carpets can be used as a barometer, to gauge the weather and your own feelings. When they are warm and dry you are in trade winds and spirits are high. When they are damp you have the miseries. When they have 6in of water over them you are scared silly. With 6ft of water your worries are over.

At present there were two pieces of carpet on the cabin floor. One I could do nothing about since it was beneath the water containers. The aft carpet I decided to wring into the bilges, at the same time taking up the inspection cover to see how much water we had taken in the last four or five hours. Solitaire’s capacity to hold water before her cabin floor consists of a sump at the back of the keel that extends to its bottom, holding approximately 20 gallons. In normal conditions I pump it out once or twice a week, if only to remove smells and any gas that might have leaked from the stove. There is room for around another 40 gallons on top of the lead keel, bringing the water level to about 5in below the floor. With this 60 gallons on board the bilges require pumping in any bad weather or it will splash through the inspection panels.

If in the Southern Ocean we took no more than 120 gallons a day we could manage quite well; pumping first thing in the morning and last thing at night would be sufficient. When I checked the bilges I thought we could last another two hours before I had to go on deck. Later I would fibreglass in the lockers, but that task I wanted to leave until as late in the voyage as possible. With both lockers sealed it would be difficult to dismantle the bilge pump to clear the blockages as I was unable to reach the seacock on the exhaust outlet.

For the first time since the storm I started to think of food and decided on a tin of stew with peas, and grapefruit for afters. I used to show my friends the logs of previous voyages, some of whom remarked how strange it was that in storms my writing became so much neater. I think this is similar to wringing out carpets; I try to hide my true feelings even from myself. If I write clearly I’m unafraid.

My log for that day read:

Managed to start sailing at 0500 hours GMT this morning. Working jib. Seas quite high and breaking. Self-steering holding reasonable course. Badly need sights for navigation. I don’t want to go too far south because of ice. At the same time am concerned about the Agulhas Current.

After another stormy night the next day’s log contained even fewer words: ‘Still storm conditions. Rain, high seas. Not very nice.’ During the night the winds dropped and dawn saw us becalmed in a massive swell, the sky still hazily grey and suspect. As I started to clean up the mess and dry the carpet I received a kick in the stomach. The ship’s log records:

Now for the bad news. Seawater from the exhaust pipe has flooded back into the motor. I have drained the oil from the sump and turned over the motor by hand to try and clear the pistons. No spare engine oil. So in a day or two will use the old oil when it has settled and try to start the engine. This voyage is not going too well at the moment.

In fact I took off the side plate of the motor, first removing the starter. The day was spent turning the engine by hand to wash out the pistons with diesel fuel. As it worked its way through to the sump I cleaned it with toilet paper. I had counted on the engine to carry us at least 100 miles if the rigging gave way! I checked the seacock on the exhaust pipe but it seemed to be tightly closed. By afternoon I felt I had done all I could, so I re-assembled everything hoping that my first voyage experience of having to make do without the motor was not to be repeated.

Soon after I had finished drying the carpet, strong gusting winds returned to confuse us all: the sea, Solitaire, and the self-steering. Finally they settled to their old habits and direction, like some monster that had dropped off to sleep for a few hours and had awoken irritably, roaring its displeasure. The heaving seas took fright and ran before it with spray flying. Within a few hours we were back in the same old conditions, chased by white cliffs, surging forward on rolling surf – and I was back to kneeling on the bunks, my head hard against the cabin roof, trying to see the mad outside world. The one consolation was that my constipation was a thing of the past. Now my only concern was that there would be enough plastic bags to last the voyage.

On Tuesday, October 7th, we had been in the storm for nearly a week and Solitaire wallowed in high, breaking seas. However, there were a few gaps in the clouds and I managed to log our position, 40°42´S, 23°55´E – 42 miles into the Roaring Forties, 360 miles below Cape Agulhas. The winds had backed from north to west and now before Solitaire stretched the Indian Ocean, a pencil mark showing that we had rounded our first Cape.

For some days the thought of opening Rome’s second parcel had tantalised me, not just for the goodies inside but for the friendship it represented. Its opening would record another milestone on our journey. I would not cheat, no matter how much I wanted to look inside, because that would mean I was giving way, and as that was not on I spent the day on my bunk with the present, looking at it, touching it. In the afternoon I managed to get a further sight, which proved that we were indeed well past the Cape. So I opened the parcel and used its contents for a special meal, finishing with two squares from a block of chocolate. The card enclosed I pinned above my chart table, the start of a new practice. Henceforward each card or letter stayed on show until replaced by a new one, whereupon the old went into the ship’s log.

Our thirteenth week at sea had proved to be our worst. Solitaire had been in conditions I would have said no ship, let alone a yacht, could survive. Looking at the chart Solitaire had been in the worst possible position when the storm started, with hurricane force winds from the north whose speed increased as they swept down the western coast of South Africa. Off the Cape of Good Hope they would hit the Agulhas Current moving at up to 5 knots in a contrary direction. Solitaire had been lying in a massive east-flowing swell when the storm reached her. I can’t see what more ingredients could have been added to make a storm worse.

Our survival inspired confidence that we really were going to make the voyage non-stop, that we had learned from my mistakes. The old book of rules for sailing a yacht around the world had been ripped to shreds and tossed over the side, old loyalties being replaced by new. The depression I had felt since leaving home I could at least understand. Solitaire and I were not making this voyage with the help of England, but in spite of its laws and bureaucracy.

Week 13 ended with our easing into the Indian Ocean. Our latitude dropped to 40°S, on the very edge of the Roaring Forties, the log showing that we had covered 8,099 miles with no major damage. The log for Thursday, October 9th, read: ‘Three calendar months at sea. A good day, in fact one of the best.’

We continued to work our way slowly north, trying to find calmer conditions so that I could work on the motor, dry out Solitaire and take a deep breath before the next stage of our voyage.