Whangerai – Lymington

December 1995 – July 1996

Just before we left Whangarei I’d studied our falling-to-bits old chart, along with the 15-year-old ship’s log of the last time we were in the Southern Oceans. The more I thought about it, the more I realised how I’d changed over the years. Looking back at the 55-year-old man who had made the previous voyage, he gave the impression of being so full of confidence and purpose, able to make immediate decisions, and carry them out with a natural instinct and ability. At the age of 70, the strong unwavering drive to finish anything I’d started was as strong as ever, but I was much slower, taking longer to sort out even simple problems. The year spent in New Zealand hadn’t helped matters. It had been a time of worry, tension and apprehension. As I read the young man’s log, I became jealous: he seemed closer to Solitaire; together they were making longer, smoother passages.

During that first week at sea we passed over the date line. On December 29th, 1995, our longitude went to 180°E. The figures changed to the west, reducing as we headed home. The young man didn’t cross over the date line until January 5th, 1981. We were a full week in front of him. He did have the advantage of being further south by 540 miles. With our larger furling headsail and strong winds from the west, we would be well in front of him when our paths crossed.

The second week at sea was an even bigger disaster. Instead of winds roaring like a lion, we had a pussycat that spent most of its time cleaning and purring. When we did get a breeze, it was hardly enough to fill the sails. At the end of our second week, we had made only 264 miles. The young man covered 682 miles.

The third week was even worse, with days of complete calms followed by gale force winds from the south-east. While trying to beat into one of these storms, the mainsail was ripped. It took all day to repair it, a day when we were blown 4 miles back towards New Zealand. During the long calms, I went back to trying to bake bread, this time making the dough into round cobs. The results were the same: I kept opening the oven door and they became flat burnt offerings, which only made me pleased that for this voyage I had plenty of other food on board. We made good only 397 miles. The young man 640 miles. By the end of that week, I had to admit that he had passed me by at least 200 miles, according to our longitudes, and was still 120 miles south of us. The thing I found annoying was that he was complaining about his slow progress. I said, ‘You should be in our bloody shoes!’ and slammed his stupid log down.

The fourth week was one of the worst I could remember at sea. The winds kept swinging around the compass. Storms from the south-east would tear into us at gale force and we would have to reduce sail to prevent them being torn to shreds. Then they would back to the west, where we wanted them, dying in strength as they went. Finally, when in the perfect position, they’d die to a complete calm. Once more we would stow all sails to prevent them being damaged by the monstrous seas. That week we logged only 192 miles. I finished my report with the prayers: ‘Please God, send us the westerlies!’

Solitaire crossed the path of the young man at the end of our fifth week at sea, on January 29th, 1996. The trouble was that he had arrived at that position on the 19th, a full ten days before us. He could have been much further ahead, but he had eased his way further north – not out of any concern for me, but simply to stay above the extreme limit of the icebergs.

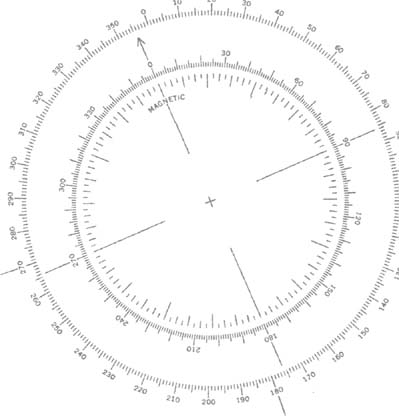

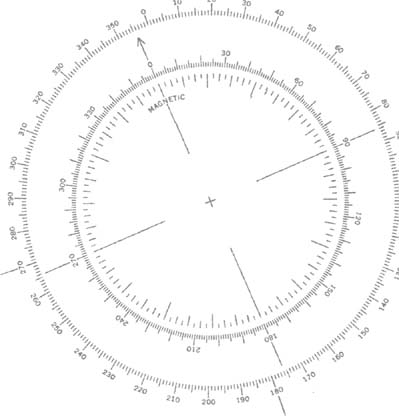

Week six ended with more of the same frustrating conditions. Sick of the slow progress, sick of always complaining, my only remarks were that we had reached the 2,000 mile mark to Cape Horn and that during the calms, with nothing better to do, I’d taken sights with my sextant. It didn’t help any; I got only the same depressing news that the GPS gave.

During week seven we were halfway to Cape Horn and for a while I thought the end of our voyage was near, and possibly the end of our lives. To add to the misery of the days of calms, we seemed to be in a world of fog and drizzle. Even without the wind the seas were heaving as though some monster was about to break the surface. Our latitude was now 49°40´S. We were just about to enter the Furious Fifties. It was a glorious day with a blue sea and sky. We had very light following winds and a high swell that kept backing the genoa. In the end I just had the main out as far as possible, with a preventer on a broad reach. The wind increased towards dark and I stowed the main and went to a full genoa. By the morning of the 9th, we were in a full gale and reduced to only a few metres of the headsail. I couldn’t make any sense of the conditions and screwed all the cockpit plywood covers in place. Still uneasy and apprehensive, I strapped the plastic water and food containers to the ringbolts in the cabin floor. During my last voyage through the Southern Oceans, I’d always kept some sail on, if only a storm jib. To go to bare poles, I’d always considered, was to put Solitaire at the mercy of the seas.

Just after midday, Solitaire started to shake like a rat that some dog had by the scruff of the neck. The wind in the rigging went to a high-pitched scream that vibrated down the length of the mast. For seven weeks I’d been crying out for more wind. It now seemed that during all that time the winds had just been building up for this, for this one supreme, killing blow. When I went on deck, Solitaire was being buried by mountains that were attacking from every direction. If I didn’t do something the mast would go. I furled in the last few feet of genoa and removed the wind vane from the self-steering. Terrified that I had made my final mistake and condemned Solitaire to her death, I went below.

I was sitting on the starboard bunk, and was just about to go back on deck to check the rigging, when the lockers on the port side seemed to lift above my head. I finished up lying on my back with the sensation that we were flying. Our landing would have done credit to Concorde. There was one heck of a crash. All the lockers burst open. Books and stores shot across the cabin, punching me with heavyweight blows. The plastic containers had been retained by their lashing, but they were now lying at all angles. Struggling out of the mess, I started to straighten the boat out. When I finished, I once more sat on the lee side. It was then I realised that Solitaire had completed a 180-degree turn as she came upright. I’d hardly caught my breath when the same thing happened again. Frightened and in a daze, as I was clearing up after the third knockdown, everything went blank.

When I regained consciousness, it was dark. So I guessed I’d been out for at least five or six hours. For weeks, I’d been wearing heavy weather gear with a towel wrapped around my neck. When I put my hand on the towel it seemed to be covered with wet tacky jam. Tracing its source, it appeared to come from a hole somewhere in the front of my head. My legs and part of my body were trapped under the water containers. When I tried to move my legs, I felt like someone had kicked me in the back. Paralysing pains shot through me, finishing at my fingers and turning them into clenched fists of agony. I thought my ribs were broken and the rough bones were trying to grind their way into my kidneys.

To add to my discomfort, I heard one of the big rollers crash into Solitaire’s side. Half the cold Southern Ocean flooded through the hatch, straight into my upturned face. I could see that the hatch was closed, which meant that the first line of defence, the canvas hatch cover, had gone.

I would like to be able to say that it was only British determination that forced me to grit my teeth and crawl up the companionway steps. The truth was, it was the normal strong desire to see if there was anything I could do to remain on this planet for a few more hours, minutes, seconds.

When I managed to pull my eyes to deck level, I could see that the canvas cover was in fact ripped in half. Worse still, the new rigging, fitted in New Zealand, had stretched and the mast was swaying from side to side – dancing to a Latin rhythm only I could hear. There was nothing I could do to adjust the rigging screws in the dark. The job would have to wait for dawn. I just hoped we would still be here to see it. By this time, I’d found that if I stayed on my hands and knees I could just about crawl.

As I went back to wrap my safety harness around the mast support, I stopped long enough to grab a bag of medical supplies and a bottle of whisky. Secured to the support, the first thing I took out of the bag was a bottle of iodine. Since I couldn’t locate the hole in my head, I poured the full bottle over the top. This turned it into a raging furnace. Leslie, I thought, that wasn’t the most brilliant idea you’ve come up with. At least you’ve found out where the hole is and it’s taken some of the attention from the pain in the back. I started taking painkillers and antibiotics, but gave the whisky a miss since I can’t stand the taste of the stuff. There was a loud double crack, as though someone had fired a rifle off the starboard side. At first I thought the stainless steel rigging shrouds were breaking away. Then, thinking of the double crack, I decided that the heavy teak beam that holds the rigging U-bolts had broken. When the sound was repeated louder than ever, I forgot my dislike of whisky and took a long hard pull from the bottle.

Dawn arrived on Saturday, February 10th, to find me still tied to the mast: freezing cold, huddled, trying to stop my teeth from chattering – partly due to the cold, but more because of fear. Water was still streaming through the hatch as the waves continued to pound into Solitaire’s side. Seawater was running from the electrics into the radio. They would be gone for sure. Most of the terror came from watching the cabin floor. By this time, the bilges would be nearly full. At any moment, I expected to find icy waters oozing around my legs. I was still taking painkillers and swigs from the whisky bottle. It didn’t seem to be having any effect. The day before I could crawl; now I couldn’t even move from the mast support. I had decided that I would save half the whisky to take with the rest of the painkillers once my legs were covered with water. If I hadn’t fitted the plywood hatch covers that would have already happened. I kept mumbling, ‘Thank God, thank God.’

Sunday, February 11th, I was still attached to the mast support. The storm force winds seemed to be as strong as ever. The only difference was that the seas were more uniform and coming from the one direction.

For nearly two days I’d become a part of the mast support, unable to move, to find food. To pass water, I was using a bottle. Even moving that through my wet weather gear and my trousers was painful and there had been accidents. Due to the fact I wasn’t eating, the whisky and painkillers had started to take effect. I felt light-headed and at times floating. I kept hearing someone grumbling and was surprised that when I tried to sing, the complaining would stop. I don’t have a singing voice, so just remembering the words and saying them seemed to help: ‘It’s been a hard day’s night and I’ve been working like a dog!’

By this time the bilges were full with about 60–70 gallons of water. The carpets had always been soaking; now it was oozing through them. The pains in my back were as bad as ever, but I did seem able to move my legs without too much trouble. I vaguely remember crawling into the cockpit and pumping out the bilges, but I don’t remember much else that happened that day. It was much later, when I read the ship’s log, that I realised that in my drunken state I’d carried out a good deal of work. The entry in the log for Sunday, February 11th, read: ‘Still in storm conditions, lying a-hull and taking a hammering. Need to work on rigging, but it’s impossible. GPS position latitude 49°19´S, longitude 125°17´W; Cape Horn 2,085 miles, bearing 95°.’

Monday, February 12th, came at the end of our seventh week at sea. It was the day that I did manage to get Solitaire moving again. Yet apart from the date and a scrawl that said ‘Severe gales’, nothing else was reported.

I knew that at some time I would have to readjust the six rigging screws. There were three either side of the boat and two in the stern. To adjust each screw, you had to straighten and withdraw two small split pins. Having adjusted the screw, the pins had to be replaced. It was more or less like trying to thread a needle. In the comfort of your own home it was easy. On a rolling, pitching boat with seas breaking over it, it was another kettle of fish. When I took a long swig of whisky and a couple of painkillers, and stuffed screwdrivers and pliers in my pocket, I knew the job was impossible. All I intended to do was check on the self-steering gear and pump out bilges. As I went through the hatch, I was singing one of the drunks’ all time favourites: ‘Show me the way to go home!’ By the time I’d done the pumping, I was ready to crawl back and hug my friendly mast. One wave had already clobbered me, pushing back the hood on my jacket, soaking all my inner clothes. The salt water had mixed with the iodine in my hair and was making its way into my eyes. My reading glasses were covered with spray. Half blind, the sensible thing would have been to try again the next day, but there again, by then I might be sober!

As each wave hit Solitaire, the water would be thrown into the air, falling to flood over her decks. Spray would follow, until the next wave arrived. With each roll, Solitaire’s lee side deck was completely under water. At times, the rigging screws would disappear. When I crawled along to the first screw, I knew I couldn’t do the job. When I pulled the first pins out, I knew I couldn’t do it. When trying to make adjustments and my hands, screwdrivers and rigging screws went under water, I sat waiting for them to come back – I knew I would fail. And when the pins were back and it was time to go onto the next one, I knew I couldn’t do it. Slowly, I found the rhythm that Solitaire was moving to. I started to keep time with her. With each roll we would both hesitate for a few moments, then move at a slow steady pace. When it was time to move over to the windward side, with the breaking waves, I thought it would be more difficult. In fact, once I picked up the new beat, it wasn’t so bad. I would hear the waves roaring in, hold onto the rigging and duck my head. Once they had gone through it seemed the decks would dry faster and last longer.

The whisky had started to wear off as I went back to the cockpit. I was about to risk a few feet of the genoa when I thought of the two rigging screws for the backstays. At least I would be working from the cockpit this time. After these final adjustments, I eased out enough genoa to allow Solitaire to make steerage way on a broad reach. I put back the self-steering wind vane and once more we were in control.

Apart from the stretched rigging, I thought another reason for the vibration was that as the new furling sail was reduced in size, the effect was to move it further up the stay, turning the rigging wire into a bowstring. On my non-stop second voyage, I’d had twin forestays with a storm and working jib hanked on. In use I kept them as low as possible, just clearing the pulpit. In future I would be forced to use smaller sails earlier and put up with slower speeds. By this time, the young man we had been racing against was miles ahead. I no longer felt jealous about his achievements and better times. All that mattered now was surviving, and rounding Cape Horn.

Pleased with the day’s work, I was about to go below when I saw the ripped canvas hatch cover. I removed it and took it with me. I still didn’t feel like eating, but I needed to replace all the blood I’d lost. During blood donor sessions in the past I’d been given hot, sweet cups of tea. By now it was late afternoon. I put the whisky bottle away and the kettle on. That night, my back started to hurt and I took a double dose of painkillers. I was still strapping myself to the mast support, but I was using a long lead and sitting in the corner of the bunk. It was difficult to sleep. Every now and again there would be the loud double report from the rifle.

Tuesday, February 13th. After drinking a few cups of tea, and taking my painkillers and antibiotics, I started to sew the hatch cover together. My safety harness was removed from the mast support and attached to one of the ringbolts in the cabin floor. By the afternoon the pains in my back were very bad.

The cracking sound from the beam was making me very edgy. Unable to concentrate, I gave up on the job for the day and started to look at the electric panel. The GPS had its own switch and that was still working. All the pilot lights for the rest of the equipment were very dim, some showing no signs of life. When I switched the transmitter on, the radio made a few squeaks and died. I removed all the front panelling and, to get my own back, I started spraying the lot with a lubricant that drives out moisture. I had thoughts of taking off my wet weather gear and changing my clothes, but there would have been little advantage: everything on the boat was soaking wet.

By that time, I could walk about bent over double. This seemed to be the normal position for lying on my bunk. A last cup of tea and two more painkillers and I lay down, pulling a sleeping bag over my head.

During that 24 hours with the furling sail reduced to storm jib size, we made one of the best runs for a long time of 116 miles. The total distance for the week was 643 miles. Considering we should have been lying in Davy Jones’ locker, I thought we’d done pretty well. The hatchway cover had been sewn and fitted. I didn’t think it would last very long and when in any violent storm I knew I would have to stow it. At least in the present gales and high seas it was keeping most of the water out. I was back in the old habit of pumping the bilges out first thing in the morning and last thing at night. But they were never more than a third full.

Towards the end of that eighth week at sea I did change my dirty, cold, soaking wet clothes for clean, cold, soaking wet clothes. Stripped off, it was the first time I’d seen my body since our troubles. I was a mass of black and blue bruises. My back was still painful, but I no longer thought I had broken ribs. Providing I didn’t make any sudden moves, I could stand upright.

At the end of week nine, we had covered another 642 miles, only one mile short of the previous week’s run. My back was still painful and I was still taking the painkillers and antibiotics. The main worry was the rifle cracks that seemed to be increasing in volume. The heavy beam that the rigging U-bolts came through had stainless steel backing plates. I believed that it was behind this plate that the beam was broken. There was one way I could stop the noise. That was to simply place my hand on the plate to feel the vibration. I could stand there for minutes and nothing would happen, move away and crack, crack...

Having found out how I could stop the noise, I then found out how it could be increased: by swearing at the bloody thing, it would soon be laughing, crackling away fit to bust. During the week I did find some drops of moisture in the fixed GPS. It was still working fine, but just to play it safe, I decided to try the handheld standby GPS. I’d tested it before leaving New Zealand and it seemed OK. Now I couldn’t get it to lock on to the satellites.

When I checked on the young man I found he was having his own problems, mostly due to a lack of food and a weight loss. Despite the fact we’d been stationary for three days, he hadn’t gained that much distance. Our weekly runs were about the same. The same gale force winds, the high breaking seas, even the same calms. Our main complaints were about the freezing seas and the cold damp cabin. He was being held up by the fact he had only small sails that he could use: a working jib and a storm jib. Whereas I had a much larger furling genoa, but I couldn’t use it in case I pulled the mast down.

Solitaire started her tenth week at sea on Monday, February 26th. Cape Horn was 800 miles away. By the end of the week we had sailed a further 600 miles. It had been a week of severe gales. Once more, we had sailed well below Cape Horn’s latitude, to make sure we weren’t driven on a lee shore. Our own latitude was now down to 57°24´S, 76 miles below the Cape. Solitaire had tried to edge her way north, but merciless seas had kept howling from that direction, driving her further away. She’d had two more knockdowns, which left a bit of straightening up, but nothing more serious.

We sailed below Cape Horn at 4.30pm on Wednesday, March 6th. Our latitude was 57°15´S, approximately 76 miles below. For the first time in weeks we had a blue sky and a calm sea. I tried to dry a few towels.

The Falkland Islands and Port Stanley were around 489 miles away to the NNE. The pilot charts showed that prevailing winds should be blowing from the south-west, Force 5 to 6. With luck, I thought, we should be in Port Stanley by the end of the week.

The young Leslie had sailed past Cape Horn on Monday, February 23rd, 1981. His latitude had been 57°00´S, approximately 61 miles below. He had enjoyed the same weather conditions. Instead of towels, he had tried to dry carpets. He was now 12 days in front. He had gained a further two days. I felt sorry. He was starving. If I had met him 15 years ago, I would have gladly given him some of my food.

Our week after rounding came to its end on Wednesday, March 13th, 1996. We were still 124 miles from Port Stanley. Instead of the winds blowing from the south-west, Solitaire had been punching her way into strong winds from the north. At times these winds had reached gale force. During the week of frustration, the one great pleasure had been listening to the radio broadcasts from Stanley. Apart from the great music, I’d felt I knew the people. There was always a report on the flights between the islands and the names of the passengers were given. I knew the name of the local pub and that volunteers were needed for some varnishing. I couldn’t wait to be sitting in its warm friendly bar.

The following day I gave up all thoughts of sitting in that pub. The weather report had forecast gale force winds from the west. With the breaking seas, we were slowly being forced away from the island. On Friday, March 15th, I scribbled a few remarks in the ship’s log:

Latitude 51°29´S, longitude 56°39´W. Port Stanley was only 38 miles away, but we had been driven past the Island. Things going very badly. A few knockdowns while trying to lie a-hull. Hatch cover once more in bits. Spent all morning trying to sort things out. GPS is still working, but now has condensation inside. Just found that I’ve lost two lighters, the one remaining doesn’t work. I have a few matches left by Tony and Irene during our holiday. It could be a serious problem. To be honest, I don’t think we can finish this voyage. We will just keep trying to head north. Everything is so cold and wet – NO REGRETS.

I took all the sail off Solitaire due to the pounding she was taking and the loud cracking complaints from the beam. Without the sails, she started to do the same 180-degree turns after each knockdown. With the hatch cover gone, once more seawater started flooding into the cabin. Before things got completely out of hand I unfurled a few metres of the genoa and went onto a reach, pulling away from land. I deeply regretted that my VHF radio was U/S and I hadn’t been able to make contact. Food would now be a problem and I could see that soon I would be in the same condition as the young man, with his agonising sores and bleeding gums. He had already gained an extra day on me, sailing past the Islands on March 2nd, 1981, a full 13 days in front of us.

By the end of our 12th week at sea we had managed only 398 miles. The Falkland Islands were 215 miles astern. I’d once more repaired the hatch cover. The crack, crack from the rifle continued. With each sound, my nerves and temper got worse. Worrying about my friends didn’t help.

Week 13 was a funny old week, with many ups and downs. The biggest down was that we only made 264 miles.

Tuesday, March 19th. The winds were light from the north. With a full genoa and mainsail, we managed to make 93 miles, staying hard on the wind. In the past I’d always tried to run the engine every two or three weeks. When I tried this time, I found seawater in the oil. I managed to filter it out and start it. I tried to get a fix with the standby GPS, without any luck.

Wednesday, March 20th. More gale force winds from the north-east. I removed the weak hatch cover. The seas seemed to be warmer, so I removed my boots – no progress.

Friday, March 22nd. I fed the latitude and longitude for Horta in the Azores into the main GPS. It gave a reading of 5,248 nautical miles, on a bearing of 022° Magnetic. Lymington would be about 6,750 miles. That day, in gale force winds, we only took 32 miles off the distance.

Saturday, March 23rd. Becalmed all night, I tried to start the engine, only to find the starter motor U/S. When I tried to use the main GPS, I found it had given up and thrown in the towel. Having taken my sextant out, I decided to give the hand-held GPS a last try. I read in the instructions that when first used from new it would take up to twenty minutes to lock onto its first satellites. I now believed that the reason it wouldn’t work was that it was trying to lock onto the satellites over New Zealand. I thought that if I removed the batteries while it was still switched on, it might cancel these and start searching. Fifteen minutes later I got my position and heaved a sigh of relief. We had taken 58 miles off the distance home.

Sunday, March 24th. Distance covered 34 miles, winds gusting from the north-east. The good news was that I had found one of my new lighters. I cut a 5-gallon plastic container in half and fitted a hosepipe tube into its cape, ready for when we had rain.

Monday 25th brought drizzle from a grey sky. We managed to catch 2 gallons of water in a very slow trickle. 23 miles covered through confused seas.

Week 14 wasn’t much better: gale force winds from the northeast that had me once more removing the hatch cover to prevent damage.

On Wednesday 27th we were in another bad gale and mountainous seas. It was a clear bright day when I saw our first ship for a month, a supertanker passing down our starboard side about half a mile away. I wrote in the ship’s log that I thought they’d seen us. I regretted I didn’t have a radio I could make contact with. I would have given anything to have been able to put Solitaire on board her. This had been a bad voyage and I’d been afraid too long. I just wanted to leave those seas and never return. I was sorry to let Irene and Tony and all of my friends down.

At the end of week 14 the good news was that our position was latitude 39°45´S, longitude 46°27´W. We had made good only 300 miles. But great news: we were out of the Roaring Forties. Whenever we had a day without strong winds I would try to bake bread. The only way I could do it was to wrap dough in tin foil. The cobs that I made came out black and flat, but I was already rationing my food so anything would help. I’d started to think that I might be forced to call into Rio in Brazil.

By the end of week 15 I was sure that food and water would be a problem and that we would be forced to stop in Brazil. There were more gales from the north-east, then long calms that at least allowed me to repair my wet weather gear and the starter motor. Distance covered was a disappointing 270 miles. By this time we were well out of the Roaring Forties at latitude 35°S. The pilot chart showed only six per cent gales in this area, against twenty-six per cent at Cape Horn. We were having gales nearly every day. It was frustrating. With the cracking rifle, nerves were at breaking point.

Week 16, Monday, April 15th. Distance covered 305 miles. There were more gales from the north and north-east, and rough seas, but they were no longer life threatening. When the cracking from the beam got too bad, I could drop all sail without the knockdowns and the whipping 180-degree turns. I tried driving wedges between the bulkhead and the beam. This seemed to deaden the sound slightly. I wrote in the ship’s log that ‘the Azores are approximately 4,448 miles, Rio 720 miles, ENGLAND 6,000 miles’.

I checked the food and found that on the present rations, we had enough to last 56 days. I removed the oil from the motor and put more fresh oil back, fitted the starter motor, and ran the engine. I made a note that the fuel lift pump had a bad leak. The last entry was that still in the Variables, with 600 miles to go to reach the south-east trade winds. Now down to low rations of half a tin of food and half a cup of rice. I didn’t really want to go into Brazil. I would even consider St Helena, 2,000 miles to the north-east.

Week 17, Monday, April 22nd. Distance covered 480 miles. We had started with a strong gale, but the rest of the week it was strong squalls, with gusting winds from every direction and confused seas. As things became warmer my weather gear had been stored away, sea boots removed and toes wriggled. After the Southern Oceans, even in the worst conditions, it seemed like Solitaire was sailing over blue velvet.

Over the years I had constantly listened to the BBC overseas broadcasts. These started to give disturbing information about Brazil: 13,000 convicts were being released from their crowded jails, high inflation, drugs out of control. Worried I might have problems due to my passport showing no Customs clearance from New Zealand and not having a visa, I decided to cut down once more on my food and water and try to make the Port of Horta in the Azores. Now, for the first time, our measuring changed from cups to tablespoons. Our ration became five tablespoons of rice, half a tin of corned beef, beans, sardines or tuna.

As week 17 came to an end, we were slipping by Rio, 460 miles to the west off our port side, heading for home. Perhaps that was the magic word driving us: ‘Home!’ Being British was in my blood. My father, his father, and for as far back as there were records, my family had been born in Herefordshire, in the heart of England. After being away for eight years, I needed to walk in its green and pleasant lands, and stand in an English pub and talk to the weird and wonderful characters the country seems to produce.

The young man had sailed past Rio on Tuesday, March 31st, 1981. His log showed that he was 600 miles off the coast, 140 miles further out to sea. He had gained an extra 10 days since we had rounded Cape Horn and was now 22 days in front.

Week 18 started with light winds, the temperature going up into the 80s. I removed my shirt and changed into shorts. There was about 10 gallons of water in the tanks and 4 more in a plastic container. We were getting squalls with a light drizzle and fresh gusting winds. There was hardly any water off the end of the boom. What there was was too salty to drink. The fuel lift pump was still leaking. I kept wrapping tape around it, then covering it with sealant. The thing slowly turned into a rubber ball, but it still leaked.

The week ended with a distance of 490 miles completed. I was now constantly hungry. But with hours spent in the cockpit, temperatures in the mid 80s, I felt more content. I started putting notes in the ship’s log to remind me how much bread and rice I was eating. The week’s run had been 490 miles. With a latitude of 16°57´S and longitude of 32°40´W, we should be in the south-east trade winds and making better progress. I’d given up believing in pilot charts years before. I was just pleased to still have a mast and be going home.

At noon on Monday, May 6th, I made the entry in the ship’s log:

Spent 19 weeks at sea! Covered only 242 miles. Becalmed for three days. Let’s hope these light southerly winds mean we are now coming into SE trade winds. Work carried out during the flat calms. Changed the Hydrovane’s self-steering rudder for a smaller spare. More work on lift pump, managed to stop the fuel leak and start the engine.

Week 20 was a good week, despite the fact that I lost my last remaining bucket, and a very powerful spotlight that Chris Parry had given me blew its bulb. The light had been used coming down the Red Sea to warn shipping that they were too close. This had been the first ship that came close enough at night to give me concern since I left New Zealand. My tri-navigation lights at the top of the mast had stopped working after our knockdowns and I’d been hoping to use the spotlight while going up the English Channel. The temperature had increased to 95°F. We logged 657 miles in the south-east trade winds.

If week 20 was a good week, week 21 was even better. On Tuesday, May 14th, we crossed over the Equator at 8.08pm. When I used the GPS it gave a reading of latitude 00°08´N, longitude 028°52´W. To celebrate, I used the last few granules of coffee to make my last cup.

When I checked on the young man, he had crossed over the Equator on Wednesday, April 15th, 1981, and toasted the crossing with a wee glass of sherry. He was now 29 days ahead of me. Food-wise he was much better off than me. That week I had cut my daily ration of rice down from five to four tablespoons.

Despite the fact that the young man was still pulling away from me and I’d been forced to cut down yet again on my rations, I would look back on that week and the days May 17–19th with greater pleasure than I had experienced on any previous voyage. On those three days we had monsoon rains with just enough wind to hold a good course with a full main. For the past two weeks I’d been getting a sucking sound from the water tanks that had make me think twice before making a cup of tea. There had been a threat of rain with heavy black clouds. Then we had the first heavy drops hitting Solitaire and bouncing off her decks. For a few minutes I watched the rivers of water run down the sail to rush along the boom and gush forth like a torrent from Niagara Falls. Never seen anything like it in all my 70 years. Never known such pleasure. Stark naked I stood in the cockpit and washed the salt from my tired body.

Having given time for the salt to be washed from the sail, I fitted my Mk1 water-catching funnel to the end of the boom. Water shot out of the end of the hosepipe as though it was connected to some high-pressure tap. Back in the cabin I dried myself. Then, selecting one of my plastic containers, I held it on the companionway steps with my stomach. When I fed the hose in, the vibrations started to say, ‘Cups of tea, cups of tea!’ By golly, I thought, this isn’t as good as holding a woman, but it runs a bloody close second. I collected 40 gallons that day and then spent some time on deck, transferring the water into the tanks. The following day I filled the containers again. Our water problems were over. I now had enough to see us all the way back to England, enough even to clean my teeth and shave. At the end of our 21st week at sea we had only made 450 miles, but the water really lifted our hearts.

By the end of week 22, we had logged a further 540 miles. The winds had been mostly from the north-east and since our course for Horta was due north, we were sailing as close as possible into wind. The cracking from the beam was becoming even more worrying. Every time I put an inch too much sail up, I thought the mast was coming down. The winds were forcing Solitaire’s track to curve to the west, away from the Islands. With our weak condition, I didn’t want to waste too much time tacking back and forth. At the end of the week, Horta was still 1,500 miles away.

At the end of week 23, we logged 650 miles, but lost over 100 miles as we were pushed to the west of the Islands. Instead of Horta being 850 miles away, the port was in fact 960 miles. More and more time was spent with my hands on the beam, trying to find where the break was. By now they didn’t seem to help. If only the winds would swing away from the north and we could come onto a reach, things would improve, I thought. Nerves were really starting to show the strain. On Thursday, May 30th, I baked my last bread. All I had left was four small burnt cobs.

By the end of week 24, things were no better. We had sailed 400 miles. Horta was 660 miles away. The Island of Santo Cruz, with its Port of Flores, the most westerly of the Azores Islands, was closer at 640 miles. On Wednesday, I’d just cut my ration down to three spoonfuls of rice a day, when a 65ft red yacht came tearing across our stern. All the crew were on deck shouting. I was doing my own shouting (and waving): ‘Food! Give me food!’ But in the blink of an eye, they were gone.

The following day, Thursday, June 6th, after winds gusting from Force 2 to Force 7 from the NNE, I wrote in the log: ‘If these winds continue, I will pass well clear of the Azores to their west and try to reach England non-stop.’ Food was a real problem. Even a small tin of sardines was having to last for two days. I found a small tin of chestnut puree, which tasted terrible, but with three spoons of rice that was my ration for another two days.

During week 25, the tins of corned beef went down to a ration of a quarter tin. I found a few dried beans. Soaked overnight, they would swell to twice their size. As we came into the high-pressure area that lies over the Azores, the winds became fickle with long calm periods. I started to run the motor with the autopilot steering. Short of diesel, I could only do this during flat calms. Week 25 ended on Monday, June 17th. We had logged 445 miles. Horta was now 310 miles away, Flores 235 miles.

Week 26 was a great week. I cut down on the rice to two spoons a day, but found that the dried beans ration could be increased to three spoons. A tin of chilli lasted five days. For the first time since leaving New Zealand, the winds started to read the pilot charts and blow from the right direction. On Wednesday, June 19th, 1996, we sailed past Flores – 55 miles to our East. All that was ahead of us now was home and England.

In the ship’s log I wrote that day:

Still it continues: grey skies, some drizzle, but constant winds from the west at Force 5. Due to the conditions over the past few days we will now try to make it all the way back to Lymington. The last few days we might be without food, but it will be well worth it, just so I can think I told New Zealand’s Safety Officer Russell Kilvington to get stuffed.

By the end of the week, we were running short of dried beans, so I opened up a tin of pineapple and had half a tin of that with half a tin of tuna and two spoons of rice. At the end of the week we had made 670 miles, all in the right direction. Falmouth, the first possible port in England, was now only 860 miles away. The noise from the broken beam was increasing, but now we were in the Gulf Stream with friendly winds. Even if we lost the mast Solitaire could find her own way.

By the end of week 27, Falmouth was only 285 miles away. We had logged 570 miles for the week, all in the right direction. I’d been back to wearing heavy sweaters since passing the Azores, with heavy weather gear. A great comfort was the lovely music I’d started to receive from an Irish station. The good old BBC was now coming in loud and clear too. The weather report was for strong winds and rain for the next three days, not the best conditions for sailing up the English Channel. I had managed to get the ship’s steaming and deck lights to work, but the all important navigation lights at the top of the mast were still not working. It would mean that, apart from dashing below for a quick cuppa, I’d be spending all my time on watch in the cockpit.

Week 28 was to be our last week at sea. All that I had left now for food were two tins of mixed fruit and a few dried beans.

Tuesday, July 2nd. Winds died during the night, hardly making steerage way. Wind Force 2 to 3 from south-east. Full genoa and mainsail. BBC forecast strong winds later. Good radio reception from Islands BBC and Devon. Fishing boats came close during the night. One came over this morning. Ration for the day: half a tin of mixed fruit with two spoons of dried beans. Falmouth 215 miles. Distance logged 70 miles.

Wednesday, July 3rd. Winds from the south-west, Force 4 to 5. Broad reach with genoa. Very bad visibility, drizzle and rain. Seas very green. Good progress in the past 24 hours. Using the GPS more to keep track of our position. Falmouth 115 miles, Lymington 270 miles. Distance logged in 24 hours: 100 miles.

Thursday, July 4th. English Channel. Strong winds from the West, still good sailing, two-thirds genoa. With luck we should be close to Lymington by tomorrow night. Then, lovely food. Lymington 170 miles. Distance logged 100 miles.

Friday, July 5th. Noon, winds from the west, gusting Force 2 to 7. Should be able to enter Lymington Yacht Haven tomorrow morning.

I was sure I had caused my many friends unnecessary worry, but was just hoping that they would appreciate how sorry I was and that it had not been done intentionally. With the perfect winds blowing us up the Channel, our first sight of England was Portland Bill.

Next came the Isle of Wight and then we were sailing by the Needles into the Solent. Old Crack-Crack made his final weak complaint. This time there were no popping eyeballs, only a smirky smile as I thought, ‘You’re dead, mate.’ Safe in harbour, I would sort him out for good.

I started to get fenders and mooring lines ready. I stowed all sails and hoisted the yellow quarantine flag. My intentions were to stay in the Yacht Haven for two nights. Then, after contacting friends, I’d go down and tie alongside Lymington Town Quay.

As Solitaire made her way up the river to the Yacht Haven, a yacht passed, going out. Her skipper shouted across, ‘Are you Leslie?’

The guy said, ‘We’d been worried about you!’

I shouted, ‘I was worried about me, too!’

The guy told me I was dead and it was then I learnt that I’d been in the national press, and on radio and TV, reported as missing at sea. My first thoughts were that I was in worse trouble than I’d realised and I wasn’t even being given the chance to apologise.

The man I’d met going out was Peter Smales. He followed me back to the visitors’ berth, where he told me he was the Haven’s PR man and Dirk Kalis had left instructions that when I turned up I was to be given a year’s free berthing. Richard and Audrey Chase took my lines. Audrey asked if there was anything else I wanted. I asked for a piece of bread. Later Dirk Kalis came down to tell me that a mistake had been made about my year’s free berthing: it wasn’t for a year, but for life!

The young man had arrived back in the Lymington Yacht Haven on Wednesday, June 3rd, 1981. We returned to the Yacht Haven on Saturday, July 6th, 1996. Our race from New Zealand had finished with him beating me by 33 days. The 15 years difference in our ages was no longer important, nor even who won the race. All that was important was we had both completed our voyages and were safely back home.

That night I was wearing pyjamas when I went to sleep on Solitaire, sure that it was all a dream and I would wake up to find I was once more in the Southern Oceans, tied to Solitaire’s mast support, a bottle of painkillers in one hand and a bottle of whisky in the other.

Next day, the newspapers and broadcasters started a mini media frenzy, reporting how ‘the starving Ancient Mariner sailed home’. The Times reported on my ‘full English breakfast, followed by strawberries’ as I did my best to restore the 5st I had lost. The Daily Mail’s David Munk wrote: ‘He is so thin you could play a sea shanty on his ribs.’ My weight had been reduced to 8st.

Even though I had returned from the dead I didn’t expect the media attention to last for more than two or three days. In fact, it went on for quite some time. The BBC asked me to go to London to do some filming for a TV show. I was told I would be paid my expenses. On arrival at the studio I was asked for my railway ticket – a cheap one-day return, costing £19. I watched in amazement as 19 one-pound coins were counted into my hand. No taxi fare. Not even a couple of bob for a cup of tea!

In the months after I returned home I was given two awards. Not so much for seamanship, I felt, but more because I’m an amateur who will not take sponsorship. One of these accolades was from The Oldie magazine, which gave me the Ancient Mariner Award, presented at a posh lunch at the Savoy Hotel, London. There were about 150 very famous people there. In fact the only one I didn’t recognise was me! After being called dead, I thought being called Ancient was a step in the right direction. I was also awarded The Ocean Cruising Club’s Award of Merit. I was over the moon with this one, since it was given by people for whom I have great admiration.

In the beginning, all the fuss, all the hugs, handshakes and questions were enjoyable. Then as I started to put on weight, people stopped recognising me in the street and life returned to something approaching normal. After the long days alone at sea it had been marvellous to be shown all that warmth and kindness – something I would remember for all my remaining years but I was pleased it was over.

Soon after I arrived back in England I bought an old 1983 Mini Metro car, which I used to drive around the country giving talks. Driving back to Lymington at 2 o’clock in the morning with maniacs in 30-ton trucks screaming past at 80 miles an hour did nothing to help the old blood pressure. I chickened out of this pastime after several months.

Meanwhile, Solitaire was still in the poor condition she was in when we arrived home from New Zealand. It really didn’t seem fair. She had done all the work and here I was fully recovered, apart from the ever-present asthma problem. My first job was to replace the wooden toe rail that runs around Solitaire’s deck.