2

Who Did What to Whom?

As we have seen, Babylonian healing therapy was divided between the activities of the mašmaššu-exorcist and the asû-“physician,” each operating within his own area of expertise, although not in a way intuitively obvious to modern medical practitioners. According to Paul-Alain Beaulieu, in later periods “prevention and cure, spiritual as well as physical, were both placed under the care of the exorcist” (Beaulieu 2007: 479). The exorcist was responsible for magical prevention of attacks of demons, angry gods, or even witchcraft and unfavorable omens, and he could also act as attending physician who visited the patient on his sick bed to give a prognosis, predicting the nature and course of the disease (see below). The exorcist had all the social advantages of being a priest. The asû-physician, on the other hand, appeared to have acted more as an apothecary who prepared the complicated recipes and drugs. As a layman, he had no access to the temple and presumably operated from a corner shop in the street or from his home. The exorcist operated primarily under the assumption that disease was ultimately caused by divine will or fate; the asû, while generally agreeing with this position, concentrated more on natural causes of symptoms (bites, excessive exposure to draughts or sunlight, kidney stone, etc.).

In order to better understand the respective roles of exorcist and physician, it may help to delve into some basic terminology. There are two different terms for “exorcist” in Akkadian, and many in Sumerian. The Akkadian term āšipu, a more literary term for exorcist, refers to the professional priest who mastered the “art of exorcism,” āšipūtu. These terms are difficult to etymologize since the cognate verb wašāpu “to exorcise” is probably derived from the noun and probably only denotes that which the āšipu was supposed to do (i.e. perform exorcisms); the circular logic tells us little (see Cavigneaux 1999: 254f.; pace Jean 2006: 19f.); Aramaic, Mandaic, and Syriac cognates are likely to be derived from Akkadian. The other word for “exorcist,” mašmaššu, was the most commonly used term within private letters and colophons of tablets, and since this term is much more widely attested in documents than āšipu, it is the term for exorcist which we prefer.48 Unlike āšipu, it is a word we can attempt to etymologize.

The word mašmaššu may derive from a root mašāšu, “to wipe,” with the Sumerian word and logogram maš.maš possibly being a Semitic loanword. A similar pattern occurs with the Akkadian word kaškaššu, “overwhelming,” derived from the root kašāšu, “to overpower.” The term mašāšu “to wipe” is not a medical term, nor is it related to muššu’u, “to rub or massage,” which is genuine medical terminology. On the other hand, “wiping” is one of the key types of ritual acts, as we know from Šurpu incantations (see above) which prescribe wiping the patient down with flour to remove his sins.49 The original meaning of maš.maš/mašmaššu may have originally derived from a term for physiotherapist, only later becoming identified as an exorcist.

An explanation of the meanings behind these professional offices deserves fuller elaboration. For a long time we thought we knew the difference between āšipu and asû, as expounded in the famous article by Edith Ritter (Ritter 1965). The āšipu, we were told, dealt with āšipūtu “exorcism”; and handled all matters of magic. The asû employed asûtu “healing arts” and acted as the doctor. All seemed so very simple.

We now wonder if these magical/medical titles in Mesopotamia are to be taken any more seriously than the title of Dottore in commedia dell’arte. Revisionists now dominate and we are no longer as certain about the roles of doctors and exorcists, magicians and sorcerers and apothecaries. The extant corpus of medical texts, for instance, contains many examples of medical texts which were either owned or copied by exorcists. Furthermore, it is not clear who actually composed the incantations within the medical corpus, since they seem so very different from incantations within formal exorcisms. On the other hand, was it really part of the physician’s brief to write spells? The patient’s role within this scheme is also unknown, since we never encounter a proper dialogue within Babylonian medical literature in which the patient is formally asked to describe his symptoms. It seems that the therapist was expected to know what was wrong with the patient without having to ask, like a diviner interpreting his signs, or like a good general practitioner or acupuncturist.

Professional Title Classification

One of the hallmarks of Babylonian scholarship was the lexical list, one of the genres of non-administrative documents to appear in the very beginning of writing, even in early archaic pictograph tablets. The lexical lists became a favorite mode of recording data, usually in the form of a list of Sumerian words or a bilingual list of Sumerian words with an Akkadian translation, and in some cases translations into other languages as well. Even many of the Sumerian unilingual lists were probably bilingual, with the Akkadian equivalent words being recited orally within the school curriculum. One of the oldest lists in the Sumerian lexical corpus is a list of “professions,” with early antecedents going back to the third millennium BC, although late versions of this list also include a group of Sumerian designations for “exorcist.” The following is a “non-canonical” excerpt from the professional list:

| [maš]-maš | = maš-ma-šu | “exorcist” |

| tígi | = a-ši-pu | “exorcist” (lit. harpist) |

| ka-pirig | = MIN (ditto) | “exorcist” |

| muš-DUla-la-ahDU | = muš-la-la-ah-hu | “snake-charmer” |

| lú-gišgàm-šu-du7 | = muš-ši-pu | “exorcist” (MSL 11 102: 204–8) |

Items on this list of exorcists are all synonyms for the mašmaššu (not āšipu), and as such include the snake-charmer and harpist, as well as a rare word for exorcist, muššipu, who carries a curved staff, mentioned once only in the standard magical compositions (Šurpu VIII 41). According to this excerpt, mašmaššu is not identical with āšipu, but a synonym.

Another listing of exorcists is “canonical” and more complete, with more information regarding synonyms for āšipu:

| [tígi] | = a-š[i-p]u | “exorcist” |

| [l]ú-tu6 -gál | = KI.MIN (ditto) | “exorcist” (lit. man having a spell) |

| kaka-tu6 -gál | = KI.MIN (ditto) | “exorcist” (lit. mouth having a spell) |

| ka-kù-gál | = KI.MIN (ditto) | “exorcist” (lit. [one] having a pure mouth) |

| kaka-ap-ri-igpirig | = KI.MIN (ditto) | “exorcist” (lit. lion-mouth?) |

| šim-mú | = KI.MIN (ditto) | “exorcist” (lit. plant-grower) |

| inim-kù-gál | = KI.MIN (ditto) | “exorcist” (lit. [one] having a pure word) |

| ni-ig-ru KAxAD.KÙ | = KI.MIN (ditto) | “exorcist” (lit. snake-charmer) |

| nigru | = muš-lah4 | “snake-charmer” |

| muš-lah4 | = KI.MIN (ditto) | “snake-charmer” (MSL 12 133: 146–55) |

This second listing of Sumerian terms for exorcist is varied and somewhat idiosyncratic, with some overlap with the first list above. The first entry is tígi or “harpist,” whom we would probably associate more with liturgy than with incantations, and the list ends with the term nigru or “snake charmer,” which probably alludes to the substantial corpus of Sumerian and Akkadian incantations for snakebite and dog-bite, etc. (see Finkel 1999; Jean 2006: 184); nevertheless, the job of snake-charmer would hardly describe the exorcist’s primary occupation or concern. The lexical list also defines šim.mú or “apothecary” (lit. grower of medicinal plants) as an exorcist, although some would prefer to see the asûphysician as an apothecary (Scurlock 1999: 78). So already three of the entries for exorcist appear controversial. The entries lú-tu6 -gál, kaka-tu6 gál, and ka-kù-gál all allude to the common designation for exorcist in Sumerian incantations, lú-mu7 -mu7 , literally “incantation-man.”

The next entry which strikes our attention is ka.pirig, which is glossed as ka-ap-ri-ig, giving us no doubt about the reading of these signs. According to the Diagnostic Handbook, the standard manual of prognosis and diagnosis, it was the ka.pirig who went to the patient’s house to take the omens, note the symptoms, diagnose the patient’s condition, and make a prognosis; the ka.pirig has no other identifiable role within the medical or magical corpus. The question is what the term actually means. Although we have some representations of priests officiating in lion outfits, probably in magic ritual contexts (Oppenheim 1943: 32), it is unlikely that pirig means “lion” here. Ungnad made the ingenious suggestion that we might have a learned writing for ka.abrig, meaning the “mouth” or “word” of the abriqqu-priest, another learned poetic term for an exorcist (Ungnad 1944: 253), although the idea cannot be substantiated by further proof. Whatever the meaning which lies behind the writing, the ka.pirig is identified in these scholastic lexical lists as an exorcist (āšipu). On the other hand, the Diagnostic Handbook never refers to the therapist making house calls as either āšipu or mašmaššu, but only as lúka.pirig, which probably indicates something more than an alternative orthography for exorcist.50

One late lexical list of professions (actually referring to types of ummânu or “professor”) was popular in the late scribal school curriculum (Gesche 2001: 130f.); the names are given below with a more precise translation of the Sumerian terms, although each is translated by āšipu “exorcist”:

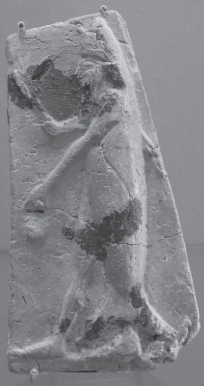

Figure 2.1 Ceramic plaque from the Assyrian period (c. 700 BC) showing an exorcist dressed as an apkallu sage (photo Florentina Badalanova Geller)

| lú ka.pirig | = āšipu | (cf. colophon of the Diagnostic Handbook) |

| lú ka.luh … | = āšipu | (“mouth-washer”) |

| lú zabar | = āšipu | (metalworker) |

| lú zabar.dab5 | = āšipu | (functionary) |

| lú én | = āšipu | (“incantation-man”) |

| lú maš | = āšipu | (see below) |

| lú maš.maš | = āšipu | (mašmaššu-exorcist) |

| lú me | = āšipu | (variant of lúmaš) |

| lú me.me | = āšipu | (variant of mašmaššu-exorcist) |

| lú pap.hal | = āšipu | (“distraught man” = patient) |

| lú hal | = āšipu | (bārû-diviner) |

| lú ad.hal | = āšipu | (bārû-diviner) |

| lú pìrig | = āšipu | (lion-man) |

| lú pìrig.tur | = āšipu | (leopard-man) |

This listing of āšipu synonyms affords plenty of surprises.51 The Sumerian words for exorcist include the one who performs the “mouth-washing” purification ritual (lúka.luh), as well as the barû or diviner (lúhal and lúad. hal).52 The lúka.pirig features as well, but we have a new entry, the lúzabar, the “bronze man,” who may have been responsible for making figurines. We even have the lúpap.hal as exorcist, which is most peculiar. Although pap.hal in this list is elsewhere translated simply as “man,” we know this term from numerous occasions in bilingual incantations where it refers to the patient or victim; he is the man who walks about restlessly, with worry and fretting. But in this list, he is an āšipu. Everything, in fact, seems to be subsumed under the title of “exorcist,” at least in academic contexts of late scribal school curriculum, which supports Beaulieu’s observation that exorcism was the most prominent discipline in firstmillennium Babylonia (Beaulieu 2007: 477).

The Exorcist in Sumerian Literature

The word maš.maš occurs first within Sumerian literature in a remarkable passage describing a contest featuring one Urgirnunna, a maš.maš who was expert in nam.maš.maš, “magical arts” (Akkadian mašmaššūtu). Within this epic account of rivalry between Enmerkar, King of Uruk and Ensuhgiranna, King of Aratta, a fivefold contest ensued between the maš. maš-exorcist Urgirnunna, defending Aratta, and Sagburu, a witch defending Uruk (Black et al. 2006: 3–11). The maš.maš-exorcist created various animals ex nihilo by throwing something magical into the river; he conjured up a carp, a ewe, a cow, an ibex, and a gazelle, while Sagburru in turn conjured up an eagle, a wolf, a lion, a leopard, and a tiger. Sagburru won. The point is that the Sumerian term maš.maš in this story really means “wonder-worker” and the abstract term nam.maš.maš refers to “wonder-working”, having nothing to do with therapy, healing, incantations, or even exorcism. On the other hand, the epic relates that Urgirnunna, the maš.maš-“wonder-worker,” resided in the Gipar temple of Aratta, which can only mean that he was a priest. We are left to speculate how the Sumerian word for a wonder-working priest later became a standard term for exorcist and healer.

Mašmaššu or Āšipu?

In colophons and in numerous texts from the first millennium BC, the Sumerian logogram (lú.)maš.maš was the most popular title for “exorcist,” which often leaves us in some doubt as to whether to use mašmaššu or āšipu as an Akkadian equivalent for Sumerian maš.maš. There are reasons, however, for suspecting a bipartite division among Babylonian exorcists. The terms āšipu and mašmaššu tend to be mutually exclusive since we hardly ever find a listing with both titles; we have personnel either described as āšipu or described as mašmaššu. Among Middle Assyrian professional titles from the late second millennium BC, we find both āšipu and the logogram maš.maš (= mašmaššu), but not both together; it is either one title or the other (see Jakob 2003: 528f.). Among later first millennium BC lists of wine consignments from Nimrud, we find officials on the wine lists being “diviners,” “exorcists,” and “physicians” (listed under their respective logograms lú hal, lú maš.maš, and lú a.zu) (Kinnier Wilson 1972: 74). In colophons, very occasionally we find the scribe recorded syllabically as a-ši-pu, but far more common is the logogram (lú.)maš.maš (Hunger 1968: 159, 167f.). The “Haus des Beschwörungspriesters” at Assur is really a household of mašmaššu-exorcists, which is the term used consistently to describe the owners or writers of the tablets from this house (Pedersén 1986: ii, 45f.). The same pattern appears in Neo-Assyrian letters, which always refer to the exorcist with the Sumerian logogram maš.maš, yet the exorcists are said to practice āšipūtu “exorcism.”53 On the other hand, the so-called Exorcist’s Manual (a list of incipits of magical and medical texts for scholastic purposes) refers to itself as mašmaššūtu, not āšipūtu (Jean 2006: 63). Another esoteric text advises that “when you work with plants, stones, and trees, or mašmaššūtu, use its commentary” (Reiner 1995: 130). Is this simply the same as āšipūtu?

We have some nagging doubts. Although many different types of activities are included within a general category of mašmaššūtu or āšipūtu, we may be dealing with sub-specialties. As we have already seen, there is the particular label ka.pirig for the therapist who actually diagnoses the patient, never the āšipu or mašmaššu. Another category of exorcist may have been the šim.mú, the “plant-grower,” or apothecary. There may be other categories which need further investigation, such as the exorcist who specializes in performing the ka.luh (mīs pî), the cultic “mouth-washing” rituals (Shibata 2008), or the exorcist who performs Namburbî rituals (Caplice 1967).

But what was the mašmaššu if not an āšipu?54 In fact, the traditional translation of “exorcist” for āšipu/mašmaššu is somewhat restrictive. What he does is usually more than simply perform “exorcism”; the exorcist was responsible for an entire range of rituals, in addition to the occasional exorcism.55 One difference does appear to emerge within the patterns of our evidence, that āšipu may have been a prestige term of scholarship and literature while mašmaššu comes from the actual parlance of practice and everyday life.

Priest vs Layman

The exorcist was a priest,56 while the asû-“physician” was a layman and entrepreneur. This difference is of crucial importance in understanding how healing was delivered. Individuals described as exorcists functioned as priests in the temple and also held appointments at court.57 We do not actually know whether the exorcist was a priest who acted as an exorcist or an exorcist who acted as a priest; we do know that his role became increasingly important within the temples in later periods and by the Hellenistic period “exorcistic arts” (mašmaššūtu) dominated the school curriculum, which was mostly confined to temples (Beaulieu 2006: 202). The exorcist was supported by prebends, a share of the temple income, although he was probably entitled to private income as well. But what about the asû? We have evidence for āšipūtu-prebends, but no evidence for asû prebends in administrative records.58 For one thing, this suggests that the asû could not enter the inner temple precincts. The late Akkadian term for a priest in general was ērib bīti, “one who could enter the temple,” which left the asû out. It is also perturbing that the asû more or less vanishes from our records by Late Babylonian times, in the latter half of the first century BC.

This is pretty much as things should be; we expect the exorcist to be a priest, since his incantations derive their power and authority from his personal relationship to the gods of incantations, usually Ea and Marduk. The asû, on the other hand, has his own relationship with Gula, goddess of healing, but his primary task is not related to the cult. In broadest terms, one goes to the exorcist if one needs a namburbî-ritual to undo a bad omen (see Caplice 1967), but one goes to the asû-physician if one has a nosebleed. Between these two poles is a full range of various options to choose from.

As a trained craftsman and entrepreneur, the asû has something in common with another important figure of Babylonian intellectual circles, the bārû “diviner,” who was also not a priest, as far as we can tell.59 The bārû was responsible for predictions about the future (mostly affecting the king and nation) based upon examining the entrails of animals, usually rams, and this type of divination was known as bārûtu. This particular type of divination is attested in both second and first millennia, although it seems to have faded away as a profession after about 500 BC in favor of the priest-astrologer-scribe whose predictions were based upon observations of movements of stars and constellations.60 Like the asû, there is no record of any bārûtu prebends, although it is conceivable that the bārû as a freelance specialist could offer his services to the temple (for payment) as well as to a private individual (including the king).61

There is one further important difference between asû, bārû, and mašmaššu: the former two could travel wherever they wished, while the mašmaššu-exorcist did not normally travel but was attached to the temple or palace. This distinction has consequences which can be traced in our sources. When the Hittite king wishes to invite an expert in healing from Babylonia, he invites a Babylonian asû-physician, not an exorcist, and he also invites Egyptian physicians (Burde 1974: 5, 6 n. 15). Mari letters speak of an asû coming from another city, Mardamân. In the parody of the Poor Man of Nippur or the Isin physician (see below), the asû travels from one place to another to ply his trade. In Hittite, the Sumerian logogram for physician in Mesopotamia, lú.a.zu, was borrowed into Hittite script and used to designate the primary healing professional, who acted as magician as well as doctor; he performed rituals as well as checking oracles (Burde 1974: 9).

What actually happened when patients met a healer, and where did this meeting take place? We do not know if the asû-physician ever met a patient, except for the occasional reference in the royal correspondence to a court physician visiting his patient. Unlike the exorcist, we cannot place the asû in any designated healing location. Although the temple of Gula (the patron goddess of healing and the asû) has been suggested as a possible healing venue (Avalos 1998: 114–28), this is hardly possible since the asû was not a priest. So where did he practice? Probably on the street, sitting on his rug and dispensing drugs. This might explain why the asû evaporates from Late Babylonian and Seleucid period archives. He was a private healer offering his services for money, and probably not very much money: we have no records of any of his private transactions because most late records are from temple archives or from large family businesses, like that of the Murašu or Egibi families (see Wunsch 2007: 238f.). Small transactions tended not to be recorded, in the same way that one never keeps a receipt from the shoemaker. The asû has simply dropped out of sight.

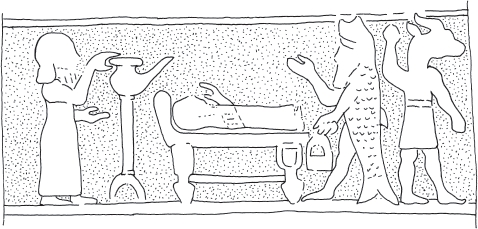

Nor does the asû appear to use any designated surgery or treatment centre, such as the reed-hut or šutukku associated with the magic rituals, magic circles, and incantations belonging to exorcism (see Figure 2.2). What about the sick person’s own house? Could the asû have made house calls? Here again, the texts tell us otherwise. The Diagnostic

Figure 2.2 Exorcism ritual carried out in a reed šutukku-hut, with one woman fumigating and another wailing; early first millennium BC (Collon 1987: No. 803; photo courtesy D. Collon)

Handbook specifically says that it was the ka.pirig-exorcist who visited the patient at home, and not the asû. The asû-physician may have been an apothecary, a herbalist, even a perfumer, but he had no need of a bedside manner, if we are correctly informed by our texts. It was the exorcist and not the physician who examined the patient from head to foot and recorded the symptoms, and it was the exorcist who needed to have an extensive knowledge of medicine in order to be able to do so. Yet there is a final irony to this story. It was the asû who actually won out in the end. The asû survived in Aramaic literature, in the form of the asya, the doctor, and Aramaic magic bowls offer asuta as the main benefit of their magical spells, while after the demise of Akkadian, the āšipu and mašmaššu disappear virtually without trace.62

Quacks and Quacksalvers

While on the subject of medical-magical professional terminology, we noted many terms for exorcist but only one term for “doctor,” asû. What about a word for quack or quacksalver? Akkadian appears to have none, but then again, neither does Greek.

Nevertheless, one can safely assume that quacks existed and that anyone with enough nerve could present himself as a master-apothecary. The temptation to act as a quacksalver must have been compelling, since there were no actual formal qualifications or diplomas for becoming an asû, except for the scions of wealthier families who studied in the scribal schools and learned to deal with medical recipes and asûtu. We have no way of knowing how widespread this training was among actual practitioners of medicine. Moreover, physicians were often itinerant, probably for good reason. Although locals would know if someone declared himself to be a physician without training or apprenticeship, an unscrupulous charlatan might well present himself in another city as an expert asû, and his foreign origins may have helped render his reputation as healer more exotic.

Furthermore, it would be difficult for an unsuspecting member of the public to know whether any prescribed medicine was legitimate or bogus. Recipes were often composed of garden herbs which were readily available and many may have relied upon a placebo effect, particularly if the patient believed that the remedy could work. Babylonian medicine, moreover, was hardly technical. Little training was required in the use of instruments, and surgery was probably performed by the barber (gallābu), if by anyone. The administration of drugs was no doubt most effective in the hands of someone with a convincing manner and friendly disposition, since “real” drugs sold by an asû and those sold by a quacksalver were probably of similar medical value.

Measures were no doubt taken by physicians to prevent poaching of patients by quacksalvers. One such measure was the common usage of Dreckapotheke within Babylonian medicine, which turn out to be Decknamen or secret names for quite ordinary drugs. The idea is that a lay person, or in this case a fraud posing as a doctor, would not be able to understand and use medical recipes, since it would become immediately obvious to the patients that the disgusting ingredients in the fake recipes, containing feces and blood, etc., did not resemble professional drug preparations. This may also be the idea behind a satire ascribed to an aluzinnu or “jester,” in which the jester poses as an exorcist. The jester as exorcist offers obviously comic recipes of foodstuffs intended to parody hemerologies (texts identifying lucky and unlucky days of the month). A sample recipe reads as follows:

The month of Kislimu: what is your diet? You shall dine on onager dung in bitter garlic and emmer chaff in sour milk. (Milano 2004: 252)

The satirical recipes themselves are drawn from the same materia medica used in medical recipes, and what emerges from the humor is that the doctor’s prescriptions are thought to be as effective as ordinary household and farmyard substances.

Another Babylonian tale, intended to amuse its audience, concerned a down-and-out but resourceful fellow named Gimil-Ninurta of Nippur.63 Having decided to exchange what little he had for one good meal, he purchased a goat, but was anxious that his relations would insist on partaking with him. He decided to offer the goat to the mayor as a gift, with the idea of being invited to dine royally with mayor. The mayor accepted the goat but threw Gimil-Ninurta out.

Gimil-Ninurta plotted his revenge against the mayor by various ruses, one of which was disguising himself as a physician from the city of Isin, the city whose patron deity was Gula, goddess of healing arts. As a visiting asû enjoying the reputation of the city of Isin, Gimil-Ninurta was invited to treat the mayor, who was most impressed with the physician’s credentials, and even remarked that “this physician is skillful!” Gimil-Ninurta insisted on treating the mayor in a dark chamber where no one else would enter, where he tied up the mayor’s hands and feet and inflicted blows on him from head to foot.

The satire of this story is based on a popular view of the physician as one who could inflict pain and suffering on a patient in the course of normal medical treatment. In other words, what the public expects from a physician’s treatment is lots of pain. A good example is a typical treatment for bladder or kidney problems, which entailed the insertion of a bronze tube into the urethra, through which drugs were blown into the patient’s penis, a painful procedure which probably offered little medical efficacy. Any attempt at surgery in Babylonia would also have involved the patient in a great deal of pain and discomfort, since there was little in the way of anesthesia. The Poor Man of Nippur tale shows that a quacksalver could hardly be distinguished from an asû, since the mayor never realizes that Gimil-Ninurta was only posing as a physician.

We usually think in terms of a bipartite division between the healing professions, a kind of therapeutic dualism: doctors versus magicians, recipe writers versus incantation experts, or asûtu versus āšipūtu. The question is whether this division between healing professionals allowed for an easy entrée for unscrupulous frauds. Another humorous composition from Babylonian scribal schools (George 1993: 63ff.) tells of a Mr Amēl-Baba, of the city of Isin, who manages to heal a patient of the effects of a dog-bite by reciting an incantation. We cannot be sure about Amēl-Baba’s professional status, since he is considered to be neither physician (asû) nor exorcist per se, but he derives his reputation from being a priest (šangû) of Gula, goddess of healing. In any case, he heals his patient with an incantation, not a medical recipe. The fact that the text considers Amēl-Baba to be a quacksalver is obvious from what follows. The patient invites Amēl-Baba to his own city of Nippur, in order to pay for services rendered, but it transpires that Amēl-Baba is so ignorant that he cannot follow simple directions given to him in Sumerian, still spoken in the streets of Nippur. The image of the exorcist as scholar is exploded in this story, to the amusement of its audience, and the text itself was composed for recitation by “apprentice scribes” (šamallû) of Uruk.

Figure 2.3 Exorcists trying to heal a patient in bed, Lamaštu-amulet (Wiggermann 2007: 107, No. 2; drawing F. A. M. Wiggermann)

The picture which emerges from this evidence gives a diversified view of types of Babylonian healers, with a rich vocabulary and various approaches to therapy. This should hardly surprise us, since there was no single standard qualification to distinguish objectively a “qualified” practitioner from an unscrupulous quack or inspired charismatic miracle-worker. What remains is for us to see how therapists, exorcists, and physicians appeared in actual documents and records.