The Second World War began shortly after dawn on Friday 1 September 1939 when two German Army Groups thrust deep into Poland. Supported by Junkers Ju 87 dive bombers (‘Stukas’), and employing the tactic of Blitzkrieg or ‘Lightning war’, the Wehrmacht raced forward, enveloping and capturing entire Polish armies which were soon overwhelmed, especially when on 17 September the Red Army of Soviet Russia also attacked Poland from the east.

Two days after Hitler’s assault on Poland, the British and French governments – which had guaranteed Poland’s sovereignty that March – declared war on Germany. That same day, Sunday 3 September, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain brought Winston Churchill into his cabinet as First Lord of the Admiralty, the minister responsible for the Royal Navy.

To the public eye, the next thing that happened was … very little. The ‘Phoney War’ lasted seven months while the Nazis ingested Poland and moved their forces westwards, but there was no fighting on the Western Front. Both the war in Finland and the war at sea were fought aggressively, however, with many sinkings on both sides, including the British aircraft carrier Courageous and the German battleship Graf Spee.

The months of uneasy waiting suddenly ended on 9 April 1940, when Hitler covered his northern flank by successfully invading Denmark and Norway, and forcing the Royal Navy to evacuate British and French forces from the latter country. This humiliation brought down Chamberlain’s government after a tumultuous debate over Norway in the House of Commons, and on 10 May 1940 Winston Churchill became prime minister. In his first appearance in the Commons in this role, on 13 May, he told the British people that they could expect nothing but ‘blood, toil, tears and sweat’, in the first of many sublime morale-boosting speeches of his wartime premiership.

On the very day that Churchill became prime minister, Hitler unleashed his Blitzkrieg on the Low Countries. Neutral Holland and Belgium were invaded, as well as France, and by 20 May General Heinz Guderian’s leading Panzer tank formations had reached the English lines at Abbeville, cutting the Allied line in half. Hopes of an effective counter-attack soon faded, and on the evening of 25 May, the British commander Lord Gort took the decision to retreat to the Channel port of Dunkirk and re-embark as much as he could of his hard-pressed British Expeditionary Force. There started a desperate race to the sea. Through a brilliant naval operation, supported by brave RAF sorties against the Luftwaffe, no fewer than 338,226 soldiers, including 120,000 French troops, were saved by 3 June, from what had at one point looked like inevitable capture. As the writer of one of these letters observes: ‘Imagine carrying 56 pounds of potatoes on your back for five hours and you can imagine how I felt.’

Yet as Churchill told the House of Commons, ‘Wars are not won by evacuations,’ and by 11 June the Germans had crossed the River Marne. The French premier Paul Reynaud resigned soon afterwards, and the Great War hero of Verdun, Marshal Philippe Pétain, filled the gap, becoming leader of the French state. He immediately appealed to Hitler for an armistice, and a peace treaty was signed on 22 June.

Contrary to the cliché, Britain did not ‘stand alone’ against Nazism after the fall of France: the British Empire remained utterly loyal to the motherland, with declarations of war against Germany and the sending of troops from Canada, Australia, South Africa, New Zealand and the West Indies. India provided the largest all-volunteer army in the history of mankind, and in East Africa the native populations enthusiastically joined up and took part in the attacks on the Italian empire there.

Now the undisputed master of the continent, Hitler began to draw up plans to invade and subjugate Great Britain, codenamed Operation Sealion. In order for them to be put into effect he needed command of the skies, so he allowed Hermann Goering to undertake the great aerial struggle that became known as ‘the Battle of Britain’. In July, throughout August and for the first half of September 1940, the Luftwaffe – with 875 bombers, 316 bombers and 929 fighters – contested the air against the RAF, which had around 650 fighters (having already lost nearly 500 in the battle of France).

Through the careful husbanding of resources by Air Chief Marshal Dowding, increased fighter construction under the new Minister of Aircraft Production, Lord Beaverbrook, invaluable early warning information from recently installed radar and observation posts, the slight performance edge of the Hurricane and Spitfire over the Messerschmitt, but above all the superb aggressive spirit of the young pilots of Fighter Command, the RAF won the Battle of Britain, in which Germany lost 1,733 planes by the end of October 1940, to Britain’s 915. On 7 September 1940, after taking heavy losses, Goering decided to switch the main target from the aerodromes and radar stations to the metropolis of London itself, a tacit acknowledgement that Britain had won. The ‘Nazi doctrines’ which one of the authors of these letters, a RAF pilot, refers to, were not about to pollute Britain after all.

The bombing of London and many other British cities – including Coventry, Glasgow, Portsmouth, Bristol and Southampton – in what was called ‘the Blitz’, was to cost the lives of nearly 43,000 British civilians. It brought the war home to ordinary Britons in a way that the Zeppelins had not really achieved during the Great War. In order to protect urban children, millions were evacuated to safety, often to rural parts of the country. If a little more brutal honesty about the horrors of war can be detected in the Second World War letters than the first set in this volume, it might be because the soldiers at the front knew that the Blitz had brought the ghastly realities of death and destruction home to civilians in 1940 in a way that hadn’t really happened before.

Although the RAF’s Bomber Command responded by attacking German cities, and the Royal Navy blockaded Germany and attempted to sink raider battleships and U-boats, for a while after the Battle of Britain there was nowhere for the Allies and the Wehrmacht to clash on land, since the Axis powers controlled the European continent and an attempted invasion there was judged suicidal. In Libya, Egypt, the Sudan, Ethiopia and along the North African coast, however, the British Army under General Wavell was able to score several significant victories over Marshal Graziani’s Italian troops, despite being heavily outnumbered.

This was not to last, however, as in February 1941 Churchill ordered forces to be diverted to protect Greece, just as the brilliant German commander General Erwin Rommel arrived in Tripoli to take command of the German Afrika Korps. On 6 April, Germany, having suborned Romania and Hungary onto its side, invaded Yugoslavia, which fell after only 11 days’ fighting. Soon afterwards, British forces had to be evacuated from Greece to Crete, where they were followed by a daring German airborne landing of over 17,500 troops under General Kurt Student. After eight days’ fighting the British were forced to evacuate Crete.

The war was going badly for the British Commonwealth, but in 1941 Adolf Hitler made two disastrous blunders which truly globalized the war and allowed the British their first genuine glimpses of possible future victory. The first mistake was Operation Barbarossa, Hitler’s invasion of the USSR on 22 June 1941, which inaugurated a life-or-death four-year struggle between him and the Soviet dictator Josef Stalin.

The other mistake came after the surprise attack that Imperial Japan launched against the American Pacific Fleet as it lay at anchor at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii on Sunday 7 December 1941, which succeeded in sinking four battleships, damaging a further five, destroying 164 aircraft and killing 2,403 US servicemen and civilians. What President Franklin D. Roosevelt called ‘a day that would live in infamy’ brought the world’s greatest industrial power into the conflict. Hitler’s near-lunatic decision to declare war against America four days later effectively spelt his doom.

Between 22 and 28 December 1941, Churchill visited Washington and Ottawa with his service chiefs and hammered out with the Americans and Canadians the key stages by which victory was to be achieved. To their great credit, Roosevelt and the US Army chief of staff, General George Marshall, eschewed the obvious response to Pearl Harbor – a massive retaliation against the immediate aggressor, Japan – to concentrate instead on a ‘Germany First’ policy that would destroy the most powerful of the Axis dictatorships first, before then moving on to crush Japan.

‘Germany First’, while making good political and strategic sense, did, however, mean that the Japanese were permitted to make enormous advances throughout the Far East in the early stages of the campaign, advances that were characterised by dreadful cruelty to the peoples they conquered and to the prisoners-of-war they captured. Catastrophe for the Allies followed, along with humiliation at Japanese hands. On 10 December 1941 Japanese aircraft sank HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse, on Christmas Day Hong Kong surrendered and in January 1942 the Japanese invaded the Dutch East Indies and Burma and captured Kuala Lumpur. On 15 February Britain suffered her greatest defeat since the American War of Independence when the great naval base of Singapore surrendered to a much smaller Japanese force. The Americans were also forced out of the Philippines.

Meanwhile, the struggle in North Africa surged back and forth between Tripoli and Tobruk. Wavell was replaced by General Claude Auchinleck, who was himself replaced by Lieutenant General Bernard Montgomery. It was Montgomery who convincingly defeated Rommel in a well-planned battle at El Alamein, Egypt, between 28 October and 4 November 1942. On 8 November, Allied forces under the American commander Lieutenant Colonel Dwight D. Eisenhower landed in French North Africa, and it was not long before the Germans were in full retreat. Tobruk, which had been taken by Rommel in June, was recaptured by the British Army on 13 November 1942.

Between January 1943 and June 1944 the Axis powers were forced to pull back in Russia and the Mediterranean, which they did in a hard-fought rearguard action, contesting every important nodal point, defensive line and communications centre. On occasion, such as at the monastery of Monte Cassino in Italy, their dogged resistance held up the Allied advance for weeks.

At the Casablanca Conference in January 1943, Churchill and Roosevelt agreed that once the Germans were expelled from Africa, the Allies would invade Sicily. After that was undertaken successfully on 10 July, Mussolini fell from power, and the new Italian government began secret negotiations to switch sides. In early September Montgomery crossed the Straits of Messina onto mainland Italy, and the American Lieutenant General Mark Clark landed an amphibious Anglo-American army at Salerno. The fighting up the Italian peninsula, which was relatively easy for the Germans to defend, proved long, hard and costly, yet too early a cross-Channel attack would most likely have been disastrous. Rome did not fall until 4 June 1944.

The very next day the eyes of the world turned to the beaches of Normandy, where – after two night-time airborne landings inland – 4,000 10-ton landing craft took six infantry divisions to five beachheads, codenamed (from west to east) Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno and Sword. In all, Operation Overlord on 6 June involved 6,800 vessels, 11,500 aircraft and 176,000 men. ‘I hope to God I know what I’m doing,’ Eisenhower said on the eve of the attack. With total air superiority, German confusion, ingenious inventions such as the PLUTO oil pipeline* and artificial ‘Mulberry’ harbours, and the courage of the English-speaking peoples, victory was assured. ‘To us is given the honour of striking a blow for freedom which will live in history,’ Montgomery told his troops, ‘and in the better days that lie ahead men will speak with pride of our doings. We have a great and righteous cause.’ The casualty figures from D-Day are estimated to be around 10,000 servicemen killed and wounded, including men from the USA, UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

Yet the town of Caen held out for a month, the battle of the Falaise Gap was not won until 21 August and Paris was not liberated until 26 August. The ever-present capacity for Nazi punishment of Allied tactical over-extension was proven on 17 September, when a huge Anglo-American airborne operation of glider landings and parachute drops codenamed Operation Market Garden attempted to secure the bridges over the key Dutch rivers and canals ahead of their armies. The Allies took Eindhoven, Grave and Nijmegen, thereby securing access over the Meuse and the Waal rivers, but the British First Airborne Division was dropped to the west of the town of Arnhem, capturing the bridge over the lower Rhine. It proved to be a bridge too far, since by 25 September it was impossible to relieve them and they were ordered to withdraw, with just over 2,000, one-fifth of the total, managing to escape death, wounding or capture.

On 16 December the Germans then launched a major counter-attack, coming once again through the wooded mountains of the Ardennes. Twenty divisions – seven of them armoured – assaulted the American First Army, while to the north SS-Oberstgruppenfuhrer Dietrich’s Sixth Panzer Army struck for the Meuse and General Hasso von Manteuffel Fifth Panzer Army tried to make for Brussels. Seeing the American front effectively being sliced in half, Eisenhower gave Montgomery command of the whole northern sector on 20 December. Montgomery managed to fight ‘the Battle of the Bulge’ successfully until the Germans ran out of petrol by Boxing Day 1944.

In January 1945, Eisenhower and Montgomery adopted a two-pronged strategy for the invasion of Germany, with the British and Canadians pushing through the Reichswald into the Rhineland from the north, while the Americans came up through the south. The land battle was supported by the heroic bombing missions of the RAF and the United States Army Air Force (USAAF), over such cities as Dresden, Hamburg and Berlin, as well as other cities and industrial and military targets. The diaries and memoirs of senior Nazis such as propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels and armaments minister Albert Speer suggest that these were highly effective in breaking German morale and dislocating industry. They came at a terribly high cost though: no fewer than 58,000 men died in Bomber Command during the war.

By mid-March most of the territory west of the Rhine had been cleared, with the German Army suffering 60,000 casualties and 300,000 taken prisoner. On 11 April the American Ninth Army reached the River Elbe at Magdeburg, only 80 miles from Berlin, and joined up with the Red Army. Two weeks later the Russians completed the encirclement of the German capital.

Adolf Hitler committed suicide in his bunker in the Reichschancellery on 30 April 1945, two days after the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini had been shot by partisans in northern Italy. Berlin surrendered on 2 May, and on the 7th, at Eisenhower’s headquarters at Rheims, General Alfred Jodl and Admiral Hans-Georg von Friedeburg signed the document of total unconditional surrender on behalf of Germany, before representatives of the United States, Great Britain, France and Russia. The next day – 8 May – was declared Victory in Europe Day (VE Day).

In the Far East, since their startling victories of late 1941 and early 1942, Japan had become bogged down. It had been fought to a standstill by General Sir William Slim’s Fourteenth Army in Burma, by General Douglas MacArthur in the Philippines and Admiral Paul Nimitz in the Pacific. There were a number of notable Allied victories, including the battles of Midway, Monywa and Iwo Jima and the fall of Mandalay, Kyushu and Okinawa. But they were all at a cost and despite these successes it was estimated by the US chiefs of staff that the invasion of mainland Japan might cost the lives of up to a quarter of a million Allied servicemen. The fanatical, often suicidal, resistance that the Japanese had offered during the island hopping campaign – and as kamikaze pilots against American ships – has convinced scholars and historians that this prediction was probably not exaggerated when extrapolated onto the Japanese home islands.

To some degree then, it was fortunate that by early August 1945 scientific developments were had been and what had been codenamed the ‘Tube Alloys’ and ‘Manhattan’ projects brought forth two different bombs, both of which were capable of using nuclear fission to create explosions of hitherto unimaginable force, and hopefully bring about peace. One was dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on 6 August, killing around 140,000 people. Japan refused to admit defeat, so a second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki three days later, killing a further 73,884 people. Japan finally surrendered on 14 August 1945, bringing to an end a conflict that in total, over six years, is estimated to have cost the lives of over fifty million people.

With the outbreak of the Second World War the professional element of the British Army, including reservists, was once again posted to France. However, following the swift fall of Poland a period of calm descended. Ernest Probst, serving with the Royal Artillery, was able to write several letters to his wife back home in England during this quiet period as he adjusted to life in the military and active service.

Somewhere in France

November 13th, Monday

My dearest Winifred,

I received a letter from you yesterday posted on the 8th so you see I am getting your post quicker than you are getting mine. That, of course, is unavoidable as the officers censor our letters in their spare time – when they get any.

Rumours about leave abound and I do not trouble to believe them. I shall expect to get leave when I open the front door with my latch-key and not before. None the less for that I’m hoping hard and trusting in Cyril’s lucky star because I’ve decided I was not fortunate enough to have been from under so continually a beneficent orb.

Don’t tell me you are lonely, darling, or I’ll probably desert. I certainly cannot get used to being without you and still expect to wake up and find myself working at [P…]. Even that would be heaven or at least a taste thereof.

It is very interesting to note that since I joined up migraines have been conspicuously absent. It’s the open air. Do you fancy the open road and a caravan? Shall we become tramps when I return? Failing that an open air job… I fancy you will have to resign yourself to that because apparently the open air is the cure for it – and having written that I shall probably be attacked tomorrow…

That firing camp I mentioned has been cancelled for some reason unknown to me so digging is once more in full swing. I today am not digging as I have a battery duty but I shall be out again tomorrow. I have just written to mother and told her I am beginning to enjoy it in suitable weather. It’s certainly bringing my muscles up…

We went to the pictures last Friday, I saw Merrily we Live. What a riot, I nearly fell of my bench laughing and it is by far the best film I’ve seen for many months. It is a peculiar thing, though, whilst on the subject of humour, that we are finding that we laugh much more readily these days at things that normally we would consider merely amusing. Maybe our sense of appreciation is becoming less critical…

Do you know that a French private receives but ½f pour jour? Ain’t that bloody awful. We must appear like millionaires to them, although I am personally broke…

Well my dearest, there is no more for now. Hurry up peace! And don’t you, wife, forget you owe me a photograph of yourself.

With all the love in the world,

Forever yours,

Ernie

The lull in the war continued throughout the winter of 1939–40 and Probst was indeed able to enjoy some leave with his wife in mid February before re-joining his unit.

20 February 1940

My darling Winifred,

I don’t know quite what to say but I must leave you a little note.

We have had a wonderful reunion but like all things it has had its ending.

Remember, darling, how much I love you in my perhaps rather undemonstrative way.

I’ll soon be home again so don’t cry about me.

I shall think of you reading this at about 7 tonight (if I have not been already attacked by sea-sickness!).

Darling, I love you,

Ernie

xxxxxxxxxx

Unbeknownst to Ernie Probst he would be making the short journey back across the Channel sooner than he would have expected. In May 1940 Hitler unleashed his Blitzkrieg on the West. Storming through Belgium and the Netherlands in short order, the British Army and their French allies were pushed back to the sea to make a final stand at a small fishing port, Dunkirk. At first it seemed unlikely that the British Army could be saved in the face of the German juggernaut. But then something miraculous occurred and from the ports and estuaries of southern England a flotilla of Royal Navy ships and civilian crafts gathered. Brilliantly coordinated by the Royal Navy, with the aerial support of the RAF, nearly 340,000 Allied servicemen were rescued from the beaches of Dunkirk. Lance Sergeant Ernie Probst was amongst those who survived the crossing despite the best efforts of the Luftwaffe.

4 June 1940

My most darling Winifred,

It doesn’t seem as though I shall get leave as quickly as I, at first, thought.

Apparently we stay here until our divisional reforming area is decided upon after which we are transferred there to refit and then it is not until we have refitted that we can hope for leave.

Anyway, darling, I am in England and absolutely safe in mind and limb with every prospect of seeing you within a fortnight.

This is a delightful place, which would be appreciated more under different circumstances. We are all getting very tired of doing nothing as we are confined to camp owing to the possibility of transfer orders arriving at any moment.

There are thirty 92nd men here including Howard Walls. I am afraid that we left Cyril somewhere in Belgium, during a retirement and I really don’t know where he is. I can only hope he is safe with some other unit.

John did not return to the unit from leave as by the time his leave was up we were moving about all over the place and so I don’t know what has happened to him either.

I am very glad that Howard is here with me as we are now pretty nearly inseparable.

We had a very narrow squeak at Dunkirk as just as we reached the boats moored to the ¼ mile long jetty five German bombers came over. Howard and I jumped on board and crossed to the outside boat of three which were moored together. The Germans dropped some bombs but we were not hit and our boat, a torpedo boat, left first and dashed hell for leather across the channel.

Howard and I solemnly shook hands when England hove in sight.

Well, sweet, looksee after yourself, more news when I see you and may it be soon.

All my love,

Yours everlasting,

Ernie

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Drop a line to M & Dad saying I’m safe. E

Some soldiers were not as fortunate as Ernie Probst and the evacuation was fraught with danger. A French liaison officer, Lieutenant Le Maitre, serving alongside 3 Corps of the Royal Signals, vividly described his experiences in a letter to his fellow officer J.W. Thraves, an extract of which is below. Thraves himself was on the beach at the time and witnessed the burning of the boat as well as the death of many fellow Royal Signallers.

On Wednesday, May 29th (1940), after escaping heavy bombing in the harbour and along the pier of Dunkerque, I sailed aboard the Crested Eagle at about 5.30pm with my liaison agent, Bassett. Two miles beyond the pier our boat was attacked by German diving bombers who dropped some big incendiary bombs. I was then standing in the inside deck on the left of the staircase; a bomb fell on the right of the staircase and I fainted for a few minutes. When I recovered myself I expected the sinking of the boat and I saw that my hands and my face were terribly burned by the fire of the bomb. All around, some wounded soldiers were shouting and roaring: I saw a small window through which I dropped myself head first and I fell on a small outside deck two yards below; there I recovered better with fresh air and was happy to find again Bassett, who was suffering from the shock but was uninjured.

In the meantime the steamer was set on fire and was beached at about 700 yards off the sand, towards which it was possible to swim quickly, but we were afraid to be made prisoners the next morning. So we decided to reach farther a British destroyer. Bassett took off my field-boots and we jumped into the sea. I saw then that it would be impossible to swim quickly enough with my uniform breeches; unhappily my hands were so badly burned that the skin was going off with the nails, like gloves… Nevertheless, I succeeded to undo all the breeches buttons, including the leg buttons, and keeping only my short pants. I swam half-an-hour before being picked up near the destroyer. Then I fainted again and when I recovered I was in a small room inside the destroyer, rolled up in a blanket: a sailor was putting some oil and bandages on my hands.

The next morning we reached Great Britain and I was carried to a First Casualty Station and afterwards to hospital. There the surgeons anaesthetised me to clean my hands and my face, and sprayed tannic acid on my hands. After further sprayings of this product my hands were covered with a kind of brown artificial skin. The flesh ought to grow again inside that sort of glove. My looking was horrible, face and ears were black and full of crusts, with enormous nose and dried lips.

The grand devotion of doctors and nurses saved my life. On June 7th sudden haemorrhages of both hands: I am getting weaker every day. Nightmares, even by day. On June 12th a Catholic priest is called to give me the last sacraments. I offer up my life for my dear France, but it is very sad to think that I shall never more see my poor wife, my boy and all the dear ones who are far from me. On June 13th my right arm is swelling, getting blur and very painful; the next morning, the surgeon opens it and an enormous quantity of pus goes off during several days. I am saved and from now I shall slowly recover.

From about June 20th I was given hand-baths; the artificial skin started to come off by pieces, uncovering a new skin on the palm and some flesh on the back of my hands; in the meantime, I was given medicines to cure my face. My ears were very painful and prevented me to sleep on the side. I was six weeks without leaving my bed, both hands confined in bandages, fed by the nurses as a baby. The back of the hands is the part needing the longest time to be healed because there the skin must be extensible and the sores of my right hand are only healed now, 29th August, three months after I have been wounded…

Another soldier to experience the desperate retreat to the sea was Major Peter Hill, a fellow reservist, who was called up to serve with the Royal Artillery Ordnance Corps. His letter, despite its cheerful optimism and faith in the British fighting spirit, certainly sheds some light on the perilous days of May 1940 when soldier and civilian alike was seemingly at the mercy of the Luftwaffe.

Major P.R. Hill

‘F’ Corps Section

2nd Ond. Fld. Park

B.E.F.

25 May 1940

My Darling Wife,

When this letter will reach you if at all I don’t know but like good British troops we always hope for the best.

The last few days Betty have not been pleasant and my dear it is no use my pretending otherwise. This continued fine weather favours the blasted German air force whilst ours is attacking his lines of communication or sitting at home kept there by windy politicians. Tell John Sully we want fighters and yet more fighters. If they appear the Germans simply can’t stand up to them. I saw two yesterday go into about six bombers bringing them down like chaff. But our pilots can’t fly 24hrs of the day. Try to impress on your friends the words of the King that we are fighting for our very existence in the world at all and that our downfall, if such a thing could be thought of, would be final and everlasting.

Every conceivable form of foulness is used by the Germans. The farmer on whose farm I am now has a son who was taken prisoner by Germans in Dutch uniforms. If any of our conscientious objectors don’t like to fight the German people but only the Nazis let them do the sort of job we had to do yesterday when the few men I have who know anything about first-aid and I had to attend to dying and injured refugees after they had been bombed. My first dead was a child of five and her grandfather. I don’t want to try and be horrific Betty and soldiers expect terrible things in war but when we see the pitiful plight of innocent people we have only one idea – carry the same total warfare into Germany and smash them in pieces for ever. The spirit of the soldiers I came across will blow things to pieces if ever a Gast tries to restore Germany as a power.

I have slept in my clothes for several days now and was up at 4am – this mainly to find a new place and hope I have chosen a nice quiet farm… The other day an officer of ours arrived with a truck full of provisions of wines and spirits. Then I picnicked in an orchard the other day on bully beef, tinned potatoes & champagne…

The weather continues to be perfect and I long for some of those gloriously happy days we have had quite alone and look forward to raising a family with you in a better world God willing. I feel sure you will take the necessary steps in this direction, it would be very encouraging if you did. If you have time dearest look around for the ideal little house you would like after the war in Barnstead, Chipstead, Epsom Downs districts, nicely in the country don’t you think. Of course it is also very nice up the river in some places. It would be better than a flat and a cottage, but what do you think?

This afternoon I think the weather is going to break. It is like thunder and will keep les avions away…

Well my darling I often look at your photo and gain courage from you. I must say that in these days a firm belief in the Christian faith goes a long way also.

Goodbye for the present dear, don’t worry, we always get away with it.

As ever

Your loving husband,

Peter

P.S. The BEF was never more alive & kicking than now.

Lionel Baylis kept a diary throughout the retreat to Dunkirk and referred to this when he wrote to his brother to tell him about the tumultuous weeks that had preceded the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force. Baylis was at this stage serving as a signalman in the 48th Divisional Signals.

No 2528408 Signm Baylis L.G.

‘F’ Section, No 2 Company

48th Divisional Signals

Hampton Park Buckwater

Hereford

Tuesday 25th June ’40.

Dear Cliff and May,

Well this letter has been a long time coming, but still, better late than never. I hope you’re both going on alright, and not being as pessimistic as the majority. I hear you had an air-raid last night. Did you hear any eggs come down or did you sleep it through? I don’t think an air-raid would fetch me out of bed unless things got extremely warm.

I don’t know whether you are still sufficiently interested to hear an account of my travels. If you’re not, swear for five minutes for me, for wasting time and paper. I will try to make it as interesting as possible and promise not to exaggerate in any way. Some of the things you will already know, but I’ve got to mention them to keep things clear…

Tuesday 10th [May 1940]. 0400hrs we were wakened by all the air-raid alarms in the district going. A.A. fire was continuous and planes droned continuously overhead. Needless to say we all tumbled out of bed and stood watching our first air-raid in pyjamas and shirt as the case may be. We didn’t see any planes brought down, but several made off with smoke pouring out of them. Well we knew or guessed something was up and at seven we heard on the news that Holland, Belgium and Luxembourg had been invaded. Bang went my leave and we prepared for an immediate move…

Thursday 16th. Ordered to move at 0330, but was cancelled. 0730 subjected to our first dive-bombing attack by German fighters. Very few casualties in our regiment though an infantry battalion marching past suffered badly. 0830 moved to our position 2 miles south of Waterloo. 48th Div supposed to act as reserve for 1st and 2nd Div, the three comprising 1st Army Corps. It didn’t turn out this way ‘but the idea was good’. Throughout the day German planes went over in groups of 50. No British planes seen and A.A. fire not too hot. Our positions were bombed again with very few casualties. Late tonight our first ‘Tactical Withdrawal’ was made…

Friday 17th. Battalion in action all day. Bombing attacks continuous. From bits of information passing over wires etc, we were beginning to appreciate that things weren’t as easy as we had thought they would be…

Saturday 18th. Reached our destination at 0430 but our stay was short lived. At 0630 the main body began what looked to me like a general retreat. I had to stay behind with our officers to destroy two wagons which had been ditched. When we had finished at 0830, rifle and machine gun fire could be heard less than half a mile away. We were moved right back to a place called Houtain and by this time were half way back into France, nor were we to get any peace here. We moved yet another 5 miles back, the Btys [batteries] opened fire and during the night we seemed to be in the middle of a circle of fire. It appears that the order to advance should have been cancelled as by the time we moved the German motorised columns had already penetrated beyond the given point…

Anyway by this time the whole British Army was on the retreat. It was simply a case of get back as fast as was possible. We travelled back to Tournai. All available transport was used to pick up the infantry. Half the blokes got separated from their units and fought the rest of the time with others. It seemed a ghastly tangle. Well the orders were to hold the canal round Tournai at all cost. We heard the news on the wireless that the battle round Sedan wasn’t going too well. Despite this and the retreat from Belgium, we didn’t have any pessimistic feelings…

On Wednesday night we were ordered to move back. Now understand this – at no point had the Germans crossed the canal but the situation elsewhere compelled us to withdraw unless we wanted to be trapped… On Monday 27th refreshed by the last 2 days we moved back to slightly west of Ypres. By this time we knew we were trapped in the north of France and Belgium. Fighting seemed to be all around us and was bitter. Artillery fire turned the sky red at night while bombing & shell fire blackened the countryside by day. Even so the worst blow was yet to fall. Early on Tuesday 28th we heard of the capitulation of Leopold.* I admit at this time none of we common soldiers appreciated the dangers. Those in command did and we set about destroying all extra kit, wireless sets, exchanges, telephones and every other bit of equipment. I should think we burnt £5,000 worth of technical stores that afternoon… Well we began to move back to the coast late at night. The journey took all night and was a nightmare. Villages and towns were bombed and machine gunned as we passed through. The roads were jammed with vehicles. Well to cut a long story short we got to within 12 miles of the coast about 0430 Wednesday 29th. I immediately fell asleep over the wheel. At midday we had orders to destroy our wagons as best we could. We daren’t fire them for fear of attracting enemy bombers which were like hornets in the sky. At 1300 hours we began our march and reached Lapanne just inside Belgium, a few miles north of Dunkirk, at 1800 hours. I was absolutely dead beat. Imagine carrying about 56lbs of potatoes on your back for 5 hours and you can guess how I felt.

Well we slept that night on the beach and with luck still with us, the morning of Thursday 30th was very cloudy. I eventually got into a boat, soaked from head to foot, at 1100hrs and was rowed out to a drifter, which left the place soon after. By this time the Germans were shelling the beach and the boats as they left. Apparently half an hour after we had left, German places machine gunned that very beach and killed and wounded 700 men. In addition they bombed and sunk a destroyer a little lower down. Well we got to England (Dover) at 2030hrs, wet and in a sorry state. A cup of tea tasted like champagne, while the railway carriage was like a feather bed…

Well I’ve tried not to let what I’ve learnt since getting back have anything to do with my tale… I will say this much, that Dame fortune followed our section. We brought every man back and only one, who lost a finger, needed medical attention. As a contrast one other section in our div signals brought 4 back out of 32…

In conclusion I’m not one of those who is eager to get back, I never want to go through another 16 days like those. I think the army is a shower of ——, badly organised and generally wants a thorough clean out. If this war goes on much longer I know I shall turn socialist and a most progressive conservative which is the same thing.

Cheers for now & all the best,

Lionel

I suppose the news of the last few days shook you a bit. It did me. Perhaps we finally realise what the German Army etc is like. Thank God we’ve got a navy and pray that the French fleet stays on our side.

Harry Calvert served in No. 149 Field Ambulance, Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC). In June 1940 he too described the danger from German bombing as the troops desperately awaited evacuation from the beaches at Dunkirk.

RAMC

Beaminster

Dorset

28.6.40

Dear P. and A.,

Many thanks for your letter which arrived this morning. You will be relieved to hear that we got through all right except for a few minor wounds. I am glad to say I am OK now.

Eddie Ritchie and young Teddy Crooks are here – the unit was very lucky at times over there and we just managed to scrape through by the skin of our teeth.

I’ve had a few of the boys killed and also a few are missing. We went through quite a lot of action in Belgium and Northern France in quite a short while and this is not an idle boast – but the British soldiers beat the Jerries every time and must have killed a half million of them on Vimy Ridge and took about two thousand prisoners.

But the French let us down badly by letting him break through and then the Belgians packed in and there we were, hemmed in on three sides with Dunkirk the only way out, so that is where we made for and was it hot I’ll say, he seemed to fill the sky with his bombers and they just played merry hell on the beach.

Well, that is where Eddie and I lost young Teddy – you see somehow or other the three of us were lost from the unit the day before by our lorry breaking down and when we got it away again the rest of the unit were miles away. So we made our own way to Dunkirk. Well we are about two miles away from there when all the excitement started – one of the Jerry bombers came flying very low along the road and he dropped a pill just about 6 feet in front of us. It just lifted that wagon as if it was a balloon and we thought our end had come and young Teddy got a nasty knock on the arm so he fell.

We managed somehow to get him off the wagon and dived into a ditch and lay there till the planes cleared off – most uncomfortable I can assure you with the machine gun bullets splattering on the road.

But never mind, we managed to fix young Teddy’s arm and we made our way to the beach. It was like jumping out of the frying pan and into the fire. The beach was like Blackpool on a Bank Holiday – it was black with soldiers. Well, we made our way to the port and got young Teddy seen to – and Eddie and I were detailed to carry the wounded on the boats.

We saw young Teddy aboard one ship – it left the port and it wouldn’t be a mile out when the bombs started to drop again. That ship was hit 5 times and I said good-bye to Teddy to myself because I thought there would have been an awful lot killed on board her – but young Teddy will tell you all about that himself when he writes. That was about the longest day I’ve ever spent in the army – we thought that night would never come. Our shoulders were aching with the wounded and about 12.30pm the officers decided to evacuate the Aid Post as there were some fresher men come to relieve us.

Well, we worked like devils in the few hours of darkness that we had but not enough time for at 4.30 just as we were making for the boats over came the Jerries to start it all over again.

I don’t think I’ve ever said my prayers as many times in one day as I did then but the Jerries got more than they bargained for this time when a dozen Spitfires came out of the blue and did they make short work of them Germans and did the lads give them a cheer – it’s a wonder you didn’t hear it over on this side.

Well, it was all over in about half and hour and Eddie and I managed to get on board a destroyer and it wasn’t long before we were making for England. Except for a few shells from the shore and two more Jerry planes it was like a pleasure cruise – thanks to the Navy – they were great – they treated us like lords coming over.

But we were pleased to see those White Cliffs – well, I ask you, were we pleased?…

Throughout the Dunkirk evacuation the RAF had only played a limited role due to the limitations of the range of the aircraft at their disposal as well as the urgent need to protect the home front. Nevertheless, their contribution played a large part in the success of the operation, their valour being officially recognised by Churchill in a speech. In total the RAF lost over 100 aircraft during the evacuation. But throughout the months of July and August the RAF would be at the very forefront of the defence of the British Isles.

Many soldiers, sailors and airmen were confronted with their own mortality on an almost daily basis. Some chose to compose a final letter home to be delivered to their loved ones if they were killed in action. Pilot Officer Michael A. Scott wrote the following to his parents in August 1940.

Torquay

21/8/40

Dear Daddy,

As this letter will only be read after my death, it may seem a somewhat macabre document, but I do not want you to look on it in that way. I have always had a feeling that our stay on earth, that thing we call ‘Life’, is but a transitory stage in our development and that the dreaded monosyllable ‘Death’ ought not to indicate anything to be feared. I have had my fling and must now pass on to the next stage, the consummation of all earthly experience. So don’t worry about me; I shall be all right.

I would like to pay tribute to the courage which you and mother have shown, and will continue to show in these tragic times. It is easy to meet an enemy face to face, and to laugh him to scorn, but the unseen enemies Hardship, Anxiety and Despair are very different problems. You have held the family together as few could have done, and I take off my hat to you.

Now for a bit about myself. You know how I hated the idea of War, and that hate will remain with me for ever. What has kept me going is the spiritual force to be derived from Music, its reflection of my own feelings, and the power it has to uplift the soul above earthly things. Mark has the same experiences as I have in this though his medium of encouragement is Poetry. Now I am off to the source of Music, and can fulfil the vague longings of my soul in becoming part of the fountain whence all good comes. I have no belief in a personal God, but I do believe most strongly in a spiritual force which has the source of our being, and which will be our ultimate goal. If there is anything worth fighting for, it is the right to follow our own paths to this goal and to prevent our children from having their souls sterilised by Nazi doctrines. The most horrible aspect of Nazism is its system of education, of driving instead of leading out, and of putting State above all things spiritual. And so I have been fighting.

All I can do now is to voice my faith that this war will end in Victory, and that you will have many years before you in which to resume normal civil life. Good luck to you!

Mick

Scott survived his initial training and deployment in 1940 and so the letter was never delivered. In 1941 he chose to draft a new version.

Royal Air Force Station

Wattisham

Bildeston 261. Suffolk

7/5/41

Dear Mother and Daddy,

You now know that you will not be seeing me any more, and perhaps the knowledge is better than the months of uncertainty which you have been through. There are one or two things which I should like you to know, and which I have been too shy to let you know in person.

Firstly let me say how splendid you both have been during this terrible war. Neither of you have shown how hard things must have been, and when peace comes this will serve to knit the family together as it should always have been knit. As a family we are terribly afraid of showing our feelings, but war has uncovered unsuspected layers of affection beneath the crust of gentlemanly reserve.

Secondly I would like to thank you both for what you have done for me personally. Nothing has been too much trouble, and I have appreciated this to the full, even if I have been unable to show my appreciation.

Finally as a word of comfort. You both know how I have hated war, and dreaded the thought of it all my life. It has, however, done this for me. It has shown me the realms where man is free from earthly restrictions and conventions; where he can be himself playing hide and seek with the clouds, or watching a strangely silent world beneath, rolling quietly on, touched only by vague unsubstantial shadows moving placidly but unrelenting across its surface. So please don’t pity me for the price I have had to pay for this experience. This price is incalculable, but it may just as well be incalculably small as incalculably large, so why worry?

There is only one thing to add. Good luck to you all!

Mick

Tragically this letter was delivered following Michael Scott’s death on 24 May 1941 while serving with No. 110 Squadron, Bomber Command. He was one of seven children, four sisters and three brothers. His brother Mark, who is mentioned in the earlier letter, was also killed during the war when he was lost at sea in 1942.

With the success of the German Blitzkrieg and the occupation of much of mainland Europe by 1941 the Phoney War seemed a distant memory. Although the Battle of Britain had thwarted any tentative German plans for an invasion of the British Isles there had been few other successful Allied actions and with the continuous bombing of the Blitz the war was fought as much on the home front as it was on the front lines. Many British soldiers were desperate to do their part to help to turn the tide and Ernie Probst of the Royal Artillery was no exception.

My own sweet Winifred,

Sunday afternoon and I am writing this in the sitting room down-stairs listening to Leslie Sarony on the radio.

These last two days have been horrible, raining all the time. It has made everything very miserable but I guess it is nowhere near so miserable as it must be in London.

I heard that the last few days have seen the Jerry over London very early and I have been rather worried about you not being home before they started. I pray every night that you may be kept safe and unharmed because I cannot bear to think of you hurt.

Things seem to be stirring up in this war business and the sooner we can have a good crack at Hitler the better I shall be pleased, so that we can be over with it all as soon as possible.

Sometimes I think that all this war makes life only the more worth living. The future holds forth such hopes of peace and security that it almost becomes an honour to have participated in the great struggle. I hope I live to see the end of it all and I’m not being miserable in bringing that into it.

I get impatient waiting for the time we can set up house together again and the very prospect of it almost justifies the war.

Well, I’ve been philosophising long enough… I love you, so looksee after yourself.

Yours forever & ever & ever,

Ernie

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Probst’s wishes were only partially fulfilled. He continued to serve with the Royal Artillery and rose to the rank of captain until the landings at Salerno in 1943 as the Allies launched their first amphibious assault on mainland Europe. The operation was a success but tragically Ernie Probst was killed and he did not live to see its successful outcome.

A key defensive position within the Mediterranean prior to the invasion of Italy was the island of Malta. With Axis and Allied armies battling for control of North Africa, British control of the island ensured that Axis supplies from Europe to North Africa could be attacked en route. The German High Command was quick to realise Malta’s strategic significance and from 1940 until 1942 the island came under sustained aerial attack. Flying Officer Geoff Stillingfleet was a British pilot based on the island as part of the defence contingent. In a detailed letter home to his parents written over a two-day period he described the virtually daily attacks to which the small island was subjected.

26/6/41

148 Squadron

RAF, H.Q., M.E

Dear Mum and Dad,

In addition to the numerous letters, cards and airgraphs I write, I usually send you a long letter once a fortnight. They, unfortunately, will take considerably longer to reach their destination, but nevertheless, I know, be very welcome.

I am going to start this letter with a few words about Malta. It is no secret that Malta has been very heavily bombed and it is about this that I am going to talk. I am told that the tiny island of Malta has received more air-raids than any other place in the war, this I can quite believe, indeed, we had an average of four a day. Before leaving England, my attitude, as you know, was one of reckless contempt towards all air-raids. However, after a few days in Malta contempt changed to respect. After six weeks there I have been an exceptionally fast runner, indeed I believe I could have rivalled even the Italians. I was capable of descending the air-raid shelters with an amazing speed and agility if not exactly with dignity (that came later with practice).

Jerry had a very unpleasant habit of, without warning, sending over sixty or seventy ‘Stuka’ dive-bombers, complete with a very large and very necessary fighter escort. Those fearful aircraft would then proceed to hurl their screaming missiles earthwards, causing considerable smoke, noise and dust, the former chiefly coming from the remains of burning German dive bombers. These attacks were annoying. Firstly, they scared us badly, exceedingly badly I might add; secondly they were always followed by a particularly long ‘alert’ caused by Jerry seaplanes searching for survivors round the coast of Malta, and finally bomb craters on the aerodrome had to be filled in and shrapnel removed from the runways.

My first experience of dive bombing was a very unpleasant one. I was caught in the open, the only available ‘funk hole’ being a sand-bagged machine gun post. Out of the sun there came formation after formation of bombers. I saw the first one enter its dive, saw its air brakes come on, and then saw the bombs leave the aircraft. I didn’t wait for more, but ran. It is impossible to describe the next twenty minutes adequately. The sky above us was filled with white puffs of hundreds of exploding shells. Nothing you thought could fly through it, but down they came one after the other, unloading the deadly bombs. Many came down but never pulled out, hitting the deck with a load crash (one narrowly missed us), another I saw exploded in mid-air showering wreckage and flak over a large area. Would they never stop, everywhere there was flying and falling shrapnel, whizzing stones and the whirr of machine gun bullets, and above all this whistling, screaming, shrieking above all noise of our gunfire the never-ending, ear-splitting explosion of heavy bombs. Suddenly the gun-fire eased off, no longer could we hear the screech of diving aircraft or the higher pitched scream of falling bombs, the last aircraft had dropped its load and to our amazement we were still in one piece. In our proximity the only casualty was a gunner with a shrapnel wound in the shoulder. German losses we learnt later were twenty-three aircraft.

27/06/41

… During the moon periods Jerry and sometimes even the Italians honoured us with frequent visits. Our hospitality was such that he often came to stay. No, Jerry definitely didn’t like Malta and he was only too pleased to jettison his bombs as soon as he possibly could…

I had a friend in Malta, a kind hearted, contented orange grower, a man with ill-feelings towards no one, yet a low flying Messerschmitt thought otherwise, he dived on him, as he was working and machine gunned him. A few days later he showed me the holes in the wall and a bullet; fortunately the pilot’s aim was bad. The following day I saw the charred, mangled remains of a German pilot; the awful sight did not make me sick. I had very little pity towards him, the unmerciful. Sorry to have kept to one subject, but there are plenty more letters following.

Your loving son

Geoff Stillingfleet’s squadron was evacuated from the island in 1941 after suffering high losses, although in his opinion his subsequent posting to North Africa was no easier with the trials of desert warfare. But it was to prove a brief sojourn and he was soon back on Malta. In April 1942 King George VI awarded the George Cross to the island ‘to bear witness to the heroism and devotion of its people’ in the face of the sustained assaults by the Axis forces. The siege itself would not be over until May 1943.

148 Squadron

RAF, H.Q., M.E

19/8/41

Dear Mum and Dad,

A friend of mine will very shortly be returning to England so I am writing this special letter for him to take with him. I say ‘special letter’ because as this will not be censored I shall be able to give you a good deal of information which otherwise I could not write.

In a letter written previously (it’s enclosed with this) I have described the Malta air raids. Well these air-raids eventually drove us from the island; our squadron suffered more from air-raids than probably any other squadron in the war. It has been estimated that over 600 tons of high explosive was dropped on our tiny aerodrome. Anyway, March 26th saw us embarking on HMS Bonaventure bound for Alexandria, incidentally this was the last voyage she completed before being sunk.

We had six or seven days in which to settle down at Kahit which was to be our main base shared by 10 Squadron. On April 5th a squadron detachment was sent out to form an advanced base in Libya. Eight lorry loads were sent out on the 100-mile journey; we followed several days later by air. I soon discovered that desert life was no picnic, drinking distilled seawater, which was hot and salty; it didn’t quench our thirst but just kept us alive. There was nothing we could get that would quench our thirst, in fact we had a perpetual thirst which at nights almost drove us crazy. Thirst is a terrible thing, but the imagination is the worst; we would lay awake at nights thinking of milkshakes, lemonades, cider and ice cold water from mountain streams. In the day time we were nearly driven crazy by the terrific heat and thousands of flies. At night the lice, bugs and cockroaches tormented us and the sandstorms arose covering our mouths, noses and hair with fine sand… Our worst experience was when we force landed at El-Adim. El-Adim was an Italian aerodrome situated in a no-mans-land somewhere between an advancing enemy and retreating British forces. Actually most of the fighting was going on further north, but nevertheless there were plenty of Jerry patrols active. The situation wouldn’t have been so serious but for the fact that we had smashed the tail wheel on landing. We stayed there two days, and a night, before we were able to get our kite in the air… We spent the time doing as much destruction as possible, shooting at the mess crockery with Italian rifles, and spraying the windows with machine gun bullets. We also painted rude pictures of Hitler and Mussolini on the wall.

After a week’s rest we again went on detachment but this time back to Malta. We first flew to Alexandria where we spent the night. The following afternoon we flew via Crete and Sicily to Malta. We spent a very enjoyable fortnight in Malta, during which time we were raiding Tripoli. Tripoli was an interesting target inasmuch as it had as much A.A. fire as any place in Germany. A great deal of it was tracer; there was so much of it that one marvelled that anyone could fly through it and not get hit. On our first visit we bombed too low and we came back more in the nature of a flying pepper pot.

On May 8th we started and are still doing what must be the longest operations in the war; the operations I refer to were those on Benghazi, they were over four hours longer than the famous trips to Venice, Milan and Turin. These Benghazi trips took twelve hours flying broken by a brief halt at an advanced base for re-fuelling.

Just before the invasion of Crete we did a number of long operations to concentrations of enemy aircraft in Greece. These trips were ten hours and another two hours returning from the advance base. During the Crete invasion we were particularly busy, each night would see twenty heavy bombers over there. We had a terrible mission, to bomb then machine gun the enemy positions and also to drop medical supplies and ammunition to our troops. Of course these were not our only targets, we have raided Searparto, Rhodes Island, Derna, Gazala, Benino, Bardia, Bairut [sic], Allepo. Since leaving England I have flown over fourteen countries.

I am in a new crew at present, and it’s one of the best crews in the squadron. Our captain has done 40 raids and has a DFC for a low level attack on the Kiel Canal. His speciality is dive-bombing. Slowly flying over a target is not so much a thrill as a strain, you just sit, make yourself as small as possible and watch the ‘flak’ coming up at you. Dive-bombing, however, is not such a strain but is just one minute of intense action and excitement. After dropping the flares, we approach the target at say 10,000 feet; the pilot suddenly shoves the stick forward and we hurtle earthwards at between 300 and 400mph. We pull-out of the dive at about 2,000 feet, sometimes much lower, and of course its then that we meet the trouble, every gun in creation seems to be firing at us. In a bright moon they can see us [at] the bottom of the dive so we gunners retaliate by firing at these ground defences and if they are Italian gunners they immediately stop firing and dive for shelter…

Operations are like many other things, when going out or over the target, I feel a little uneasy and I make up my mind that I hate it, and that I will give up the whole game as soon as I can, and yet on the return trip and when on the ground I decide I want to continue doing ‘ops’ as long as possible. Actually they must have a certain hold on me, they act rather like a stimulant or drug for when-ever I am on the ground for a few days, I start getting irritable, depressed and discontented…

Just a few final words, don’t worry, it’s not half as dangerous as it sounds. On the Corinth Raid, which was considered an exceptionally dangerous one, there were forty aircraft operating, thirty-two were dropping bombs and making low-level attacks to draw the fire away from the mine-laying aircraft. Total casualties, two people slightly injured by shrapnel. Remember also, if we ever should get hit, I can bale out in twenty seconds. Another thing, should I be reported missing the chances are I shall be a prisoner of war, or at any rate safe.

Well I don’t think there is anything more to say. I hope you are all as well and happy as I am.

Your loving son

Ever since his arrival in North Africa in February 1941, Erwin Rommel, later known as the ‘Desert Fox’, had sought to go on the offensive against the British and Commonwealth forces. At the end of March 1941 he made his move. The Afrika Korps drove the British back and isolated and surrounded the Libyan port of Tobruk, starting what was to be an eight-month siege. Captain Gordon Clover served with the 149th Anti-Tank Regiment, Royal Artillery, and recorded life under siege in a detailed letter to a friend.

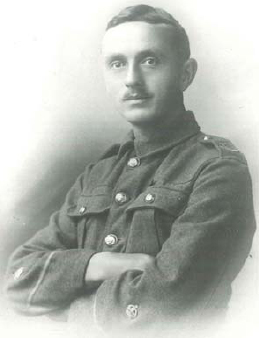

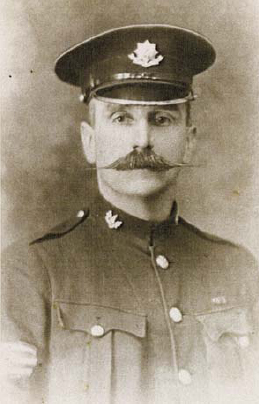

Lieutenant William Leefe Robinson VC, famed for shooting down a Zeppelin over London during the First World War. © IWM (Documents 200)

Company Sergeant Major Milne, 1/5th Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders, who fought in the Second Battle of the Marne in July 1918. © IWM (Documents 1635)

Corporal Laurie Rowlands, 15th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry, experienced his ‘baptism of fire’ on the Ypres Salient. © IWM (Documents 2329)

Sergeant Francis Herbert Gautier, who wrote a heart-rendering letter to his daughter, Marie, after he’d been wounded. He sent similar letters to other family members. Courtesy of the family of F. Gautier.

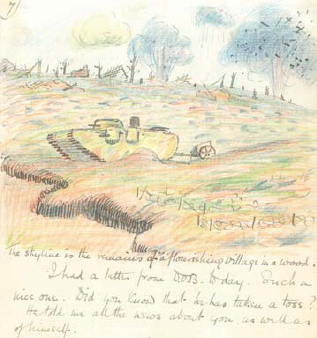

Reverend Canon Cyril Lomax, a Church of England Army chaplain, served with the Durham Light Infantry in France from July 1916–April 1917. He illustrated his letters from the front line, providing his family with an insight into the first tank attack (top) and the arrival of post in a billet (bottom). © IWM (Documents 1289)

Men and horses from the Cavalry Division, British Expeditionary Force, retreat from Mons, August 1918. © IWM (Q 60695)

Front line trenches during the First World War. © IWM (Q 4649)

A Company, 11th Battalion, Cheshire Regiment, occupy a captured German trench at Ovillers-la-Boisselle on the Somme in July 1916. One soldier is on sentry duty, using an improvised fire step cut into the slope of the trench. The more established fire step facing the other way was used by the Germans before the trench was turned. © IWM (Q 3990)

The trench system was often very confusing due to the sheer number of trench lines and the ziz-zagged pattern they followed. As a result, the different trenches often gained their own names, as seen here. © IWM (Q 4180)

This letter, written in the shape of a kiss, was sent by George Hayman, a private in the Lancashire Fusiliers, to his wife in June 1916 before he was sent to France. He died two months later. © IWM (Documents 1647)

Captain Samuel Gordon served with the British Army as a doctor during D-Day on an American Landing Ship Tank (LST) which was later used to evacuate casualties. © IWM (Documents 774)

Bob Connolly, an NCO with 8th Battalion, Rifle Brigade, on his wedding day. Connolly landed on Juno Beach on 13 June 1944 and took part in a number of battles around Caen. © IWM (Documents 13168)

Lance Corporal John A. Wyatt, 2nd Battalion, East Surrey Regiment. He fought to contain the Japanese invasion of Malaya in 1941. © IWM (Documents 8531)

Lieutenant Brin L. Francis, 8th (Belfast) Heavy Anti Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery, served in the Far East, while his brother, David, was involved in fighting around Caen in 1944. © IWM (Documents 8240)

‘The Withdrawal from Dunkirk, June 1940’ by Charles Ernest Cundall. The troop-filled beaches, evacuation attempts by the Royal Navy and bombing by the Luftwaffe are all clear to see. © IWM (ART LD 305)

In a posed propaganda photograph British pilots are seen ‘scrambling’ to their aircraft during the height of the Battle of Britain. © IWM (HU 49253)

The Blitz: a Heinkel He 111 bomber flies over London on 7 September 1940. © IWM (C 5422)

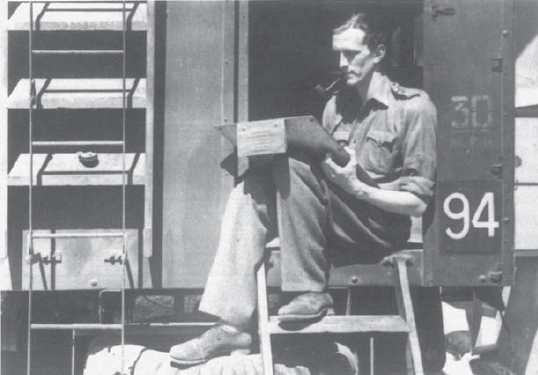

Captain Christopher Cross of 2nd Battalion, Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, is shown here relaxing and writing. He took part in the glider landings across Normandy in June 1944. © IWM (Documents 771)

The 5th Cameron Highlanders prepare Christmas puddings in the Western Desert, December 1942, illustrating the fact that there were sometimes periods of light relief. © IWM (E 20598)

Pilot Officer Michael A. Scott photographed here wearing his RAF wings. Like many pilots and servicemen during the war, Scott wrote a final letter home, to be delivered if he was killed in action. © IWM (Documents 431)

Reverend Don Siddons, Staff Chaplain at Eighth Army HQ, conducting a communion service in the desert during the Second World War. © IWM (Documents 9143)

Defence of Tobruk: the Royal Artillery utilise their guns to repel the Germans in the desert, 1941. © IWM (E2887)

In a posed photograph, British infantry are shown rushing an enemy strong-point through the dust and smoke of enemy shell fire at El Alamein. © IWM (E 18513)

El Alamein, 1942. A mine explodes close to a British truck as the infantry move through an enemy minefield to new front lines. © IWM (E 18542)

Support troops of the 3rd British Infantry Division assemble on Sword Beach, 6 June 1944. The soldiers pictured here include engineers and, in the background, medical orderlies preparing to move wounded men off the beach. © IWM (B 5114)

Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke, Winston Churchill, Field Marshal Sir Bernard Montgomery and Lieutenant-General William Simpson walk across a Bailey bridge over the Rhine on 26 March 1945, marking the success of the Allied sweep across Europe. © IWM (EA 56602)

Men of the 1st Battalion, Dorsetshire Regiment, with South Korean soldiers during the hand-over of the ‘Lozenge’ position to the 4th Republic of Korea (ROK) Infantry Division, c.1954. © IWM (CT 1908)

During a lull in the fighting in Korea, British soldiers enjoy a game of football, c.1952. © IWM (BF 10081)

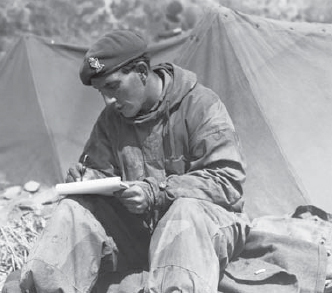

A trooper of the 8th Battalion, King’s Royal Irish Hussars writes a letter home while serving in Korea. © IWM (BF 522)

Lieutenant Robert Gill, photographed with Doreen, his then girlfriend. He wrote letters to her from Korea, detailing his movements. © IWM (Documents 13204)

A Bren gunner pictured here in a concealed ambush position while on patrol during the Malayan Emergency. © IWM (MAL 171)

British troops from 1st Battalion, King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, are shown here on patrol through a Malayan jungle, c.1952. © IWM (BF 10387)

HMS Sheffield on fire after being hit by an Exocet missile fired from an Argentinian aircraft. © IWM (FKD 64)

Heavily laden British troops during the land campaign on the Falklands. Here they are waiting to board a helicopter in 1982. © IWM (FKD 2124)

3rd Battalion, Parachute Regiment, pictured here with the battalion flag in Port Stanley after the Argentine surrender on 14 June 1982. © IWM (FLD 364)

A British Army M110 self-propelled gun in action during the First Gulf War in 1991. © IWM (GLF 1280)

An RAF Tornado F3 in flight over the burning oilwells of the Gulf in the 1990s. © IWM (GLF 762)

From a vantage point at Basra Technical College, a sniper of 1st Battalion, Irish Guards provides covering fire for Royal Engineers as they attempt to extinguish an oil well fire during the battle for Basra City in 2003. © IWM (OP-TELIC 03-010-34-003)

Four British soldiers of 3 Division Headquarters and Signal Regiment conduct a foot patrol on the outskirts of Basra during Operation Telic 2, September 2003. © IWM (HQMND(SE)-03-053-009)

149 A. TK. Regt, RA

M.E.F.

14 Oct 1941

My dear Bill,

Your letter dated 5th September arrived safely. Thank you so much. It is grand to hear from you at any time and especially so under the present circumstances of my existence. I was very glad to hear that you and Rosemary are well and happy. I’m in the same condition of body and mind myself as a matter of fact!

Every condition of one’s life that I have experienced so far has its [redeeming], amusing and enjoyable parts. I have come to find it a rule of life. Every time that things get worse life still remains humorous and even enjoyable when you think it is not going to be! Experiences such as this damned well help you not to dread anything.

Let me describe shortly my immediate surroundings. I am sitting at a [rough] table in a deep dugout built of sandbags and old ammunition boxes and covered with a great variety of scrap… It is dark. There is a hurricane lamp on the table giving a dim light and throwing strange, dark shadows on the walls [of] the canvas, indeed nothing can be seen clearly a few feet from the lamp. Rats are scurrying around the sandbags, sending trickles of sand down the earth walls… I am warm (winter is beginning)… Jerry Jones (who sends you his love) sits on the other side of the table playing what he calls ‘golf’ with a pack of cards. I have a packet of ‘Woodhams’ beside me (I have had a weakness for ‘Woodhams’ since about 1920 when I used to smoke them…) and my rum ration. The rum is good and strong and makes one tingle all over. Now doesn’t that describe a happy situation for a fellow who is making himself live from day to day without worrying about the future?

We are ‘in action’ somewhere in a desert (I mustn’t say which!). There are a variety of explosions – not near enough to cause any anxiety – there are machine guns going off intermittently. When things ‘hot up’ a bit, as they probably will in an hour of two, I shall pop my head out of the dugout to watch the streams of flames and coloured lights and tracer bullets. The firework display is often worth seeing and it is interesting to know in which sector it is happening (if not in one’s own!) and then speculate what, if anything it signifies.

Now let me reassure you, if it is necessary, this may all sound alarming, but it isn’t really, even to me, and I should know! It is amazing how few casualties there are, even when things are hottest. You are as safe in a dugout as slit trench as anyone can expect to be, and (I have seen it happen as well as heard of it happening numerous times) shells and bullets can be all over the place causing a great deal of noise, and yet no one [is] even hurt…

The things I do find a bit alarming, especially at night, are the landmines. They are everywhere and no one [here] knows exactly where they are. The anti-tank ones are not supposed to go off if a man treads on them. The British ones are probably fairly safe in this respect. But there are a lot of fancy ones which our troops hid in haste … and if you are near them they say it is unwise to breathe heavily!… Another of our lads volunteered to guide a truck loaded with some of our ‘foreign allies’ through a minefield close to us. He led it straight into a mine which exploded. He was knocked flat on his face, the truck was blown up and all the ‘foreigners’ jumped out, shouting and cursing in about six different languages!… Well, old boy, you know the rest…

All the best Bill, old man. See you both, I hope, before too long. The war can’t last forever and we are bound to win! Cheerioh!

Your ever,

Gordon

While the British position remained perilous in the Middle East, a new threat arose in Asia: Japan. Manchuria was occupied in 1931, followed by the outbreak of war with China in 1937 and border clashes with the Soviets in 1939. Following the outbreak of the Second World War in the west, Japan sought to take advantage of the colonial powers’ weakness by occupying all of French Indochina in July 1941. The relentless Japanese advance had provoked an American embargo on supplying oil to Japan, a position followed by the British and Dutch authorities in the region. Japan had been pushing aggressively outwards in the region in search of the natural resources needed to maintain her growing empire and, deprived of access to vital raw materials, decided to take what they needed by force and launched a concerted attack on the US naval base at Pearl Harbor and Dutch and British colonial possessions in the region in early December 1941.

Lance Corporal John Wyatt served with the 2nd Battalion, East Surrey Regiment, as the British struggled to contain the Japanese invasion of Malaya.

L/C J. Wyatt

D Coy

British Battalion

Malaya

Dec 21-41

Dear Mum & Dad & Elsie,

Hope this finds you as safe & as well as I am at present… Well mum before I start I would like you all to give thanks to God at church for the mercy he has shown not only to me but to the whole Battalion. 3 times I have just waited for death but with God’s help I am still here. I have felt all along that with all your prayers God would keep me safe. I will only give you one instance of it. 10 of us were in a trench in a little … village in the jungle, we were told last man last round, for we were surrounded by Japs and as they were closing in on all sides some of the chaps were saying good-bye to each other, and I was really frightened at the thought of dying but as the minutes dragged on I resigned myself to it, then all of a sudden 3 aircraft came over, was they ours?…

Down came the bombs all round us, all we could do as we crouched there was to wait for one to hit us, but that good old trench saved our lives for it swayed and rocked with the impact, about one minute after they flew off believe it or not 4 tanks rumbled up the road, and [gave] our position hell. They flung everything at us, grenades, machine guns, but still we crouched in that little trench. We could not return fire for if we had showed our heads over the little trench the advancing Japs were machine gunning us, all of a sudden we heard a shout ‘run for it lads’, did we run, but the last I saw of the brave officer who said it, I shall never forget him, as we ran past him I saw him pistol in hand pointing it at the Japs holding them off while we got away. I haven’t seen him since.

Anyway we waded through about a mile of padi, bullets whistling past all the time, but we reached the jungle and safety, then on to find the British lines, we tramped 30 miles that day living on jungle fruits. The fight started at 7 in the morning, we reached safety at 5 at night. Then for sleep, food, clean clothes, shave, for we had been at the front for 8 days without sleep or clean clothes, for we have lost everything, the Japs have got everything, all my personal stuff, photos, prayer book, everything, but thank God I am still here. Most of the Battalion reached safety but a lot of poor chaps are still missing, some of my friends too… Excuse pencil as this is the first chance I have had to write in a fortnight, so please make do with this. Keep smiling Elsie & I hope to see you next year xxxxxxx.

Well mum our worries are over, we have just been told that we are moving back, and our job is to stop looting so all our fighting is finished… We certainly knocked the old Japs about while we [were] there did we, we are miles better than them and we are sorry we wont be able to get another smack at them, I will have to hurry as the candle is burning out. So I will say good-bye for now, Dorrie xxxx. Jimmy, George, Mrs Ward, Church, rest of family and neighbours, please don’t worry, God bless you all and keep you safe.

Your ever loving son,

John

xxxxxxxxx

xxxxxx

xxxxx

The Japanese steadily advanced down the Malayan peninsula until they came to the city of Singapore, the ‘Gibraltar of the East’ and a major British naval base. The city came under siege on 8 February 1942 and fell to the Japanese on 15 February 1942, described by Winston Churchill as the ‘worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history’. Lieutenant Colonel Tim Taylor was one of the lucky few who managed to escape just before the fall of the city.

Colombo

10 March 1942

The thought of how much I have to tell you rather appals me. You know that I want to tell it to you and I love writing to you, but this will be a volume before I finish. I’ll say straight away very briefly how I got here and then I’ll go into details of the story.

I was ordered away, quite unexpectedly, on Friday, 13th February, heading for Java. We were bombed at sea next morning and made for the nearest land… We crossed that by slow stages, in various forms of transport and left the [censored] in a warship, and arrived at Java on the 22nd February. We had a few days there and then came on here – were ‘torpedoed-at’, but they went underneath! and I’m now awaiting orders for the next stage. A month ago I was resigned for what seemed inevitable – being a prisoner of the Japs – and now things are altered completely.

That’s the bald outline and I’ll try and fill in the details. I’d better start way back when I moved out of the Adelphi and went to share a house with Braithwaite and Shean…

We were getting a fair amount of bombing at night just then as there was a moon out and there again we were well off, as the town was the usual target and we could lie in bed and feel that we were reasonably safe. By day the bombing was increasing and they had an almost daily visit to the docks area. I spent many an hour in the Railway Station shelter waiting for things to clear.

Those evacuations! The more I saw of them the more I was pleased you got away when you did. As soon as I had finished my job of getting people off ships we were hard at it putting women on, usually by night to avoid what raids we could. The scrum of cards and people in those docks was indescribable and when an alert went I had many anxious moments before all was clear again. Bombs in those crowds would have caused absolute chaos, but we were fortunate and nothing happened till the last afternoon I was in Singapore, when there were some casualties unfortunately. Three of us were on a big ship when one went right down an open hold, but again we were lucky and merely felt a bit shaken…