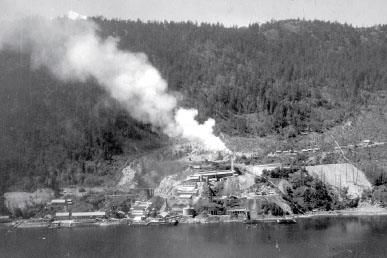

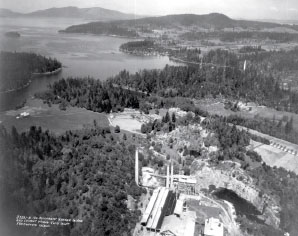

The cement plant at Tod Inlet in the 1920s. The tile plant remains, but the plant chimneys are inactive. Courtesy of the Butchart Gardens.

The cement plant at Tod Inlet in the 1920s. The tile plant remains, but the plant chimneys are inactive. Courtesy of the Butchart Gardens.

The closure of the Tod Inlet cement plant was accomplished with little fanfare. The Vancouver Daily World announced the news in the back pages on June 18 under “Mining Notes”: “The British Columbia Cement Company has closed its plant at Tod Inlet, near Victoria. The plant employed principally Chinese labor.”

There seems to have been little notice of the closure in the Victoria newspapers, nor any reaction. Four days after the official closure, the Victoria Daily Times reported on the presentation of a gift to plant superintendent Harvey Knappenberger by his employees: “On the occasion of the closing down of the Tod Inlet plant of the B.C. Cement Company on Saturday last, H.L. Knappenberger … was presented with a pair of military hair brushes, suitably initialed and engraved.”75

As the closing of the plant in 1921 coincided with the taking of the Canada census, we have a good record of the men who were impacted. When the census of Tod Inlet was taken on June 16, 1921, there were 66 men recorded as working at the Tod Inlet cement works.

There were 24 white workers, many of them immigrants from Europe, and 42 men in the “Chinese Quarters” of Tod Inlet. The census gives an interesting picture of the men from China. Five of the men were 50 or older; the oldest was 60. The youngest was 25 and four others were 30 or younger. Only two of them were not married. Twenty of the men had arrived in Canada in 1911 and 1912. The others had arrived as early as 1881 and as late as 1918.

All were recorded as “labourers” except two: Chow Fung On and Goody On were each listed as “Chemist Assistant.” They would have worked in the company lab helping run the constant testing of the cement. Both were listed as speaking English.

With the closing of the plant some of the Chinese workers at Tod Inlet probably went to work and live at Bamberton, while others began to work at the Butchart Gardens or sought other work in Victoria. Some may have gone back to China. The Chinese workers played an important role in the Bamberton story as well. There were 39 men from China already working at Bamberton in 1921, one as a foreman, the others as labourers at the cement works. At Bamberton, they had their own bunkhouse and cookhouse. They were diligent workers in the kilns, mills, quarry, yard and laboratory.

The engineers and other plant workers who stayed on with the company and continued to live at Tod Inlet had to make the daily commute to Bamberton by boat. At first the men were taken to Bamberton by Oscar Scarf of Tod Inlet in his 32-foot double-ender Mary S., a former fur-sealing boat from the Pribilof Islands, named after his daughter Mary. Scarf also had a contract to carry mail from Tod Inlet to Bamberton. He lived at Tod Inlet on his boat until 1946.

With most of the company activities now centred on Bamberton, mail delivery at Tod Inlet became more complicated. Edwin Tomlin, president and managing director of the BC Cement Company, was appointed postmaster for Tod Inlet on February 2, 1921, and held that position until his death in 1944. The post office was moved from the plant’s office building to the former cookhouse when the cement plant buildings were abandoned. James R. Carrier was an assistant postmaster under Tomlin from about 1921.

The active cement plant at Bamberton in 1966 with the kilns in the foreground. Alex D. Gray photograph.

Norman Parsell, one of the Tod Inlet men who followed the industry to Bamberton, began work in the quarry there, first as a driller’s helper, and then as a driller in 1922: “Those big old burly machines with the tripods and weights were heavy hauling around that quarry!”76

In 1919, the BC Cement Company had taken over ownership of the Bamberton, the 50-foot ship built in 1913 by the Hinton Electric Company of Victoria, and in about 1923 this ship took on the daily role of carrying men from Tod Inlet to Bamberton and back.

The population of Tod Inlet rose and fell with the highs and lows of the cement plant. The number of men listed in Wrigley’s BC Directory for Tod Inlet went from 36 in 1918 to a low of 19 in 1924. For the next two years the list reached a new high of 55 names, most employees of BC Cement.

Adapting to change seemed to be standard procedure for the cement business as it adjusted to the times, the demands and the competition. Even the name of the product changed. Their cement was no longer sold as Vancouver Brand Portland cement, probably to avoid confusion between Vancouver Island and the city of Vancouver. It was now Elk Portland cement, perhaps inspired by the elk that were once common in the hills around Saanich Inlet. When advertising their high-grade Portland cement in 1920, the British Columbia Cement Company still listed their “Works” at Tod Inlet as well as Bamberton.

The Bamberton at Tod Inlet in the ice and snow. Alex D. Gray photograph.

The new Elk brand shipping sack used by the BC Cement Company. Author’s collection. David R. Gray photograph.

One of the big dryers from the Tod Inlet plant was sold to the Canadian Kelp Company of Sidney, BC, in about 1917. It was then purchased by the Portland Cement Company of Oswego, Oregon, in 1922. A long-time employee of the BC Cement Company at Tod Inlet, James Haggart, was now in charge of the work of moving the dryer to Oregon by ship and rail. H.L. Knappenberger, who had been superintendent of the Tod Inlet plant, also moved to Oregon at the same time to work for a different cement company.

After the war, the demand for cement finally increased, as cities replaced older wooden buildings with new, more permanent and fire-safe structures. By 1923 more capacity was needed. The company took the largest of the kilns at Tod Inlet out of the old plant building and moved it to Bamberton. The weight and size of the kiln must have made for a tricky set of manoeuvres to say the least. The installation of the “new” old kiln increased production from 2,000 to 3,000 barrels each day.

Robert Butchart retired as managing director of the BC Cement Company in 1926 at the age of 70 and turned the directorship over to Edwin Tomlin, who had been treasurer of the company for many years. Butchart was made Freeman of the City of Victoria in 1928.

While things were slowing down at Tod Inlet in the 1920s, to the west, on the other side of the Partridge Hills, a new community was just beginning. The land between Saanich Arm and Tod Inlet, which includes the Partridge Hills, is sometimes referred to as Willis Point, though the name really applies to the point of land at the northern corner. This whole area was an important place for the Tsartlip people. Traditional hunting and fishing camps were situated along the coast. The local W̱SÁNEĆ name for this whole area is SX̱OX̱ÍEM, meaning still or rising waters. The area was first surveyed in 1894, and two sections at the northwest end were granted by the Crown to Sewell Moody in 1905. The land began to be settled in the 1920s.77

According to Elder Dave Elliott Sr., white men were not allowed there, but Tsartlip chief David Latasse sent Sam Whittaker and his First Nations wife there as land markers.78 The Whittakers lived in a cabin at Smokehouse Bay, south of Willis Point, in the 1920s. They picked berries and fished, selling their catches in Tod Inlet and at what is now Brentwood.79 Whittaker was a taxidermist who worked for the BC Provincial Museum (now the Royal BC Museum) from 1911 into the 1920s. He also offered boats for rental, and his name appears under Tod Inlet in the 1930 BC Directory as “Whittaker S boats for hire.” Josiah Bull, who built a wooden shack near Smokehouse Bay, was the only other resident at the time. Within 20 years, this would change.

With the increased use of cars and buses came improved roads, and the BC Electric interurban railway suffered substantial losses. The service finally came to an end in 1924. No more would the freight service haul freight and logs, nor would mail and milk from local farms be carried to Victoria.80 The rails were removed in 1925, and the route once again became a local roadway, eventually becoming part of Wallace Drive from Brentwood south to Tod Creek Flats, and Interurban Road on towards Victoria.

The Bamberton cement works, 1930. National Air Photo Library.

Even though production increased throughout the 1920s, in about 1930, at the beginning of the Great Depression, the Bamberton plant was closed and most of the employees were laid off, including all of the Chinese men. Only a skeleton crew was kept on to watch over the plant. The Chinese workers did not return when the plant reopened.

During the years of the Depression, Tomlin, the managing director, made a number of improvements to the Bamberton plant. One was the retrieval from the old cement plant at Tod Inlet of another tube mill for grinding limestone and its installation at Bamberton.

The BC Cement Company planned annual events for the families of its employees, including those who lived at Tod Inlet. There were picnics every year, among other summer excursions. Mary Parsell recalled an excursion to Maple Bay on the company boat. “Oh! what an enjoyable time we had. They provided all the food and gave tickets to all the children for ice cream and pop.”81 Another time—sometime after 1929—they were taken to Deep Cove on the Island King (purchased by the company in 1929), and in later years they went to the federal government’s Experimental Farm in Saanichton for their annual outing.

After closing the main plant at Tod Inlet in 1921, the company continued to operate a tile plant at the site, making cement drainage tiles and flower pots on a small scale. The plant was situated at the shore, between the large wharf and coal shed and the power station, just east of the coal unloading dock. The foreman of the plant was James Carrier, who had arrived at Tod Inlet with his wife, Evelyn, and family just after the World War I. The family appears in the 1921 census as living at Tod Inlet; Wrigley’s Directory of 1921 lists Carrier as postmaster for the village.

James Carrier, postmaster and foreman of the tile plant. Carrier family collection.

The tile plant was a simple building with corrugated tin for the roof and siding. Inside was a 1.5-metre mixer machine. Sand and cement were poured into a chute that led to the machine. The tile machine made straight, tube-shaped tiles of solid wet cement, which the plant workers had to bore out to make them hollow before the cement had completely set. They also made special tile fittings in hollow T, Y and C shapes by hand.

The flower-pot- and tile-making process was complicated. The men had to let the tiles partially set overnight after they were hollowed out, 50 tiles to a tray, then stack them the next day and spray them with water for two or three days until they set completely. Specially made nozzles created a fine, fan-shaped spray. The cement flower pots, which came in at least six sizes, the smallest 4 inches across and the largest 12, also had to set under a water spray.

The big ships were still seen occasionally in the inlet in the 1930s. Cement to make the flower pots and tiles came from Bamberton on the company ships or by tug and barge, usually five hundred 87.5-pound bags at a time. The sand for the tile plant came from Victoria or Metchosin on a barge, and the men unloaded it using wheelbarrows.

The tile plant, with the peaked roof, at Tod Inlet in 1973. David R. Gray photograph.

Cement drain tile on the beach at Tod Inlet, 2018. David R. Gray photograph.

Flower pots from the Tod Inlet tile plant. David R. Gray photograph.

A spray nozzle from the Tod Inlet tile plant. David R. Gray photograph.

From 1921 to 1936 the company freighter Teco carried cement from Bamberton to Canadian west coast ports, but was also seen in Tod Inlet on occasion. In 1928 Teco’s master, R. Hunter (age 41); the mate, James Smith (age 28); the second engineer, James Parsell (age 63); and the winchman, Peter Hunter (age 29), all lived at Tod Inlet.

The company steamer Matsqui, purchased in 1919, also visited Tod Inlet. In May 1923 Matsqui ran aground on a rock at D’Arcy Island, where in the late 1800s the Canadian government had quarantined Chinese people who had leprosy, without medical care, leading to its reputation in the Chinese community as the “Island of Death.” Matsqui was pulled free and sent to Yarrows Ltd. in Victoria for repairs.

Mike Rice, who lived at Tod Inlet, recalled that initially it was Chinese men who worked at the tile plant in the 1920s. When Claude Sluggett began working at the plant in 1932, he took over from three Chinese men who worked there. He thought they might have gone on to the Butchart Gardens. At age 23, Sluggett’s wage was 30 cents (about five dollars in 2020) an hour; he lived in the Tod Inlet bunkhouse, where the cost of each meal was 35 cents. Sluggett worked at the tile plant until war broke out, and he went back to Bamberton in 1939.

Dem Carrier, son of the plant foreman, was born at Tod Inlet in 1925. When he began working at the tile plant as a teenager in 1940, sand was brought in on a barge nudged in by a tug. Workers had to unload the sand across large planks over four and a half metres of water to the shore. They also had to unload bags of cement that the Island King brought from Bamberton, for local sale and for making the flower pots and cement tiles.

When I interviewed Lorna Pugh (née Thomson) about her memories of the Chinese and Sikh workers of Tod Inlet, she gave me a little book of memories of the 1930s, Brentwood Bay and Me: 1930-1940. I had no idea at the time that her book would turn out to be such a gold mine of stories about Tod Inlet. Her memories provide a glimpse into the social life of the community, consisting of about 150 people in the 1930s, from the perspective of a teenager.

Sunday afternoons were often spent walking to the Carriers’ home in Tod Inlet, having tea and listening to the 5 P.M. news and Big Ben on the radio before walking home, a distance of approximately two miles. The Carrier household was a friendly place and I have spent many enjoyable hours in their company. My mother and Mrs. Carrier were very close friends … Their friendship led to Joyce Carrier and myself sharing many outings together. We did much exploring in the Partridge Hills and named one of the creeks flowing into Tod Inlet “Joylorn.” We loved to hike or row across the inlet to explore this creek and thought it mysterious because it went underground for a way and then reappeared.82

Spring was my favourite season. Everything seemed to come alive. The Indian drums and their chanting at [ceremonies] on the Tsartlip Reserve competed with the frog chorus in the swamp. Both could be heard from our house and seemed to usher in spring.83

I still roamed the hills [as a teen] but usually in the company of others instead of alone. Good Friday hikes to Durance Lake with a group of local school friends, Girl Guide hikes and compass tests in the Sooke Hills and up Mt. Work under the capable hands of our Guide Leader, Ethne Gale, are happy memories.84

This song comes from the BC Cement Company’s Community Song Book, a book that was created “for Use at Community Functions at Bamberton.” But the lyrics obviously would have had a lingering connection to Tod Inlet.

NOTHING BUT CONCRETE

(To the tune of “My Bonnie Lies over the Ocean”)

The children of Israel in Egypt

Made brick in four thousand B.C.,

But we have escaped out of bondage,

It’s nothing but concrete for me.

Chorus:

Concrete, concrete, nothing but concrete for me, for me,

Concrete, concrete, nothing but concrete for me.

Don’t build a cottage of lumber,

I want something modern, you see

And building of lumber’s a blunder,

It’s nothing but concrete for me.

(Chorus)

Don’t spoil any roads with macadam,

For that is as frail as can be;

As long as I’m paying the taxes

It’s nothing but concrete for me.

(Chorus)

In picking the dates for our lifetime

The fates worked with kindly intent

In placing us here on this planet

To live in the age of cement.

(Chorus)

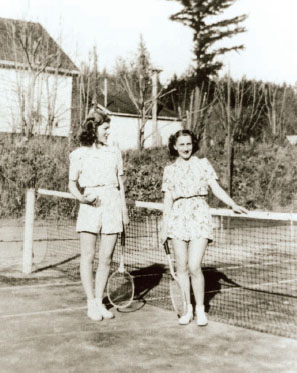

The tennis court at the Carrier home. The net posts are still in place, and one of the walking trails passes right over the court. Carrier family collection.

The old West Road Hall was a meeting place for the social and recreational needs of Brentwood and Tod Inlet for many years. The hall was built at the corner of Lime Kiln Road (now Benvenuto Avenue) and West Saanich Road on land owned by Jack Sluggett. When the local Women’s Institute built its own hall in 1924, the old hall began to be used for basketball, and the Tod Inlet cement company men formed their own team.

When a few of us showed interest, Miss Jean Bagley, the primary teacher at West Saanich School used to take us to the West Road Hall and taught us the rudiments of badminton. This game became very popular in the early thirties and a court was built in an unused building in the B.C. Cement plant in Tod Inlet.85

When the Mount Newton High School was built nearby in 1931, students from the area no longer had to take the bus into Victoria to attend high school. Lorna first went to Mount Newton in 1934 after grade 6.86

Lorna and her school friends enjoyed occasional wiener roasts on Fernie Beach at night and swimming or playing tennis at the Carriers’ on days off. Sometimes they fished for perch off a wharf below the village or from the Butcharts’ boathouse.

In the latter part of the 1930s, the young people of the area were delighted on cold winter nights when the Carriers would flood their tennis court and visitors were allowed to put on their skates in the warmth of the Carriers’ kitchen. The Carriers used to scrape and reflood the court after skating was finished so that it would be in top condition the next day. They also served coffee and delicious refreshments to top off the wonderful evenings.

One very cold year Tod Inlet froze sufficiently that skating was possible out to the buoy off Fernie Beach. It was said Jack Stewart’s team of horses was taken across the inlet to test the ice. Mrs. Carrier, who was not a strong skater, in her stately manner pushed a chair in front of her for support.87

Bamberton in ice. Carrier family collection.

Rescuing a boat sunk by the ice at Tod Inlet in 1935. Note the laundry house in the background to the right and the foreman’s house behind the men. Alex D. Gray photograph.

Photos from the Carrier family photo album show James Carrier, the postmaster, pulling a bag of mail across the inlet to the edge of the ice, where the tug Bamberton waited to take the mail across Saanich Inlet to the plant at Bamberton.

The Reverend Robert Connell, an Anglican minister who was later the first leader of the BC Co-operative Commonwealth Federation party (a predecessor of the New Democratic Party), wrote articles about local natural history and geology for the Daily Times and Daily Colonist newspapers in the 1920s and 1930s. He visited Tod Inlet often, and in his articles, a series entitled “Rambles Round Victoria,” he described in observant detail the plants and geology of the area.

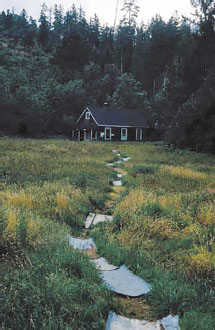

Connell described what it was like to follow the road down to the inlet from the old interurban line in 1924:

The road descends into the valley which, extending from Prospect Lake, passes into the head of the inlet by way of a little stream whose waters go tumbling seaward under a simple bridge of timbers. Here the maidenhair [fern] luxuriates in the damp interstices of the rocks shaded by the overhanging trees and shrubs…. The road, in its lower part, at present the scene of woodcutting operations with their accompaniment of fresh surfaces and resinous odor, winds up the hillside and eventually brings the traveler to a little cottage in an open clearing starred with flowers.88

Kangaroo at the Inlet in winter, with Tod’s Cabin in the background. Alex D. Gray photograph.

He was probably referring to the cabin at the head of the inlet, just south of the mouth of Tod Creek on the small terrace above the shoreline. This old log cabin was known as “Tod’s Cabin” (though it had no connection to the inlet’s namesake). It had become pretty dilapidated by the 1930s. Joyce Jacobson (neé Carrier) recalled the building, known to them as “the Hut,” as a shack papered with newspapers—in particular, a 1905 edition of the Calgary Herald with a headline reading “Reform of the Senate Required.” Some things never change!

Connell’s writings give an interesting perspective on the old limestone quarry just east of Wallace Drive, now called Quarry Lake. Water began to seep into the quarry sometime around 1921 after drillers checking the depth of the limestone deposit drilled through to the water table.

Connell described the quarry both before the flooding, in 1924, and after, in 1931. In the earlier account, he wrote, “At the crossing of the derelict electric railway we looked down into the quarry of the cement company, very bleak and cold, with its bare walls of dark grey limestone. Vegetation has scarcely as yet succeeded in establishing itself in the inhospitable crevices, and the contrast is great with the lawns and flowerbeds of the other quarry, once as naked as this but now the celebrated ‘Sunken Gardens.’”89

Seven years later and ten years after the aerial tramway and quarry were abandoned, Connell wrote about what was still to be seen at the now water-filled quarry:

Then come the appendages of the quarry, the overhead railway, engine-house, pumps, loaders, and what not. What a sight the quarry presents! It is filled from end to end with water, which over the pale rock below has a blue-green color, and in its motionless surface the walls of marble with their abrupt changes of tint, their crevices and cracks, and all the irregularities due to Nature or to the operations of the quarryman’s art, perfectly reflected.90

In those days the quarry was not fenced off as it is today, and people went there to swim. Quarry Lake was also a bathtub for some of the berry pickers who worked on neighbouring farms. Many would often head there after work with their towel and a bar of soap.

People also swam in the flooded lower quarry—the first quarry, abandoned before the cement plant was built. In the summer of 1931, 20-year-old Patrick Hogan, a soldier from Heal’s Camp, was swimming with friends in the lower quarry, then climbed up onto the roof of the vacant plant. In an unfortunate accident, he was electrocuted when he touched a live high-power wire leading to the crusher machine in the building. The secretary of the BC Cement Company told the inquest into Hogan’s death that although the plant was not in operation, the live wiring had been retained for occasional use. Signs had been posted stating that the land was private property and that swimming was prohibited, but they had been torn down. Sometime after this incident, the quarry and plant were fenced off, though they remained accessible from the beach at low tide.

Quarry Lake in the 1960s (top) and in 2019 (bottom). David R. Gray photographs.

When the film studio Central Films of Hollywood was shooting a series of films in Victoria in the mid-1930s, the inhabitants of Tod Inlet had a front-row seat for one of the movies. Dem Carrier and other youngsters were asked to help with the filming of a scene in the 1936 movie Stampede where outlaws spooked a herd of horses in an attempt to kill the hero, played by Charles Starrett.

The “Black Canyon,” the scene of the stampede, was actually the Tod Inlet gulch, the cement company’s electric railway cutting, where clay from the upper pit and rock spoil from the upper quarry had been carried west towards the plant by the electric railway trolley. Dem Carrier helped in the action shot by throwing clods of dirt at the horses, all from the Thomson and Sluggett Farms, to keep them moving.

Newspaper advertisement: “Victoria’s Own Motion Picture Production! Peter B. Kyne’s Roaring Yarn of Thundering Hoofs! ‘Stampede’ Filmed Entirely in Victoria and Vicinity under the Title ‘Gunsmoke’ with Charles Starrett, Finis Barton.” Author’s collection.

A section of a poster for Stampede showing the star, Charles Starrett, wrestling with an antagonist in the Tod Inlet gulch. Central Films, 1936. Author’s collection.

The “Black Canyon,” just west of the entrance to the main trail through Gowlland Tod Provincial Park at Wallace Drive, 2018. David R. Gray photograph.

The making of the movie Stampede was not the first roundup of horses at Tod Inlet.

On the northwest side of Tod Inlet, along the coast and inland towards Willis Point, is an area where the Tsartlip people took their horses to graze in a grassy opening.91 A fence marking the Tsartlip territory ran across the land, from Tod Inlet to Saanich Inlet, approximately in line with the high smokestack at the old power plant at Brentwood Bay. Tsartlip Elder Dave Elliott Sr. remembered often hunting along that fence. The whole peninsula south of the Willis Point itself had beautiful springs year-round and plenty of forage. Elliott’s people used to leave their livestock there while they went to the Gulf Islands to fish. They drove their horses and cattle up to the mouth of Tod Inlet and swam the animals across so they would be inside the fence. The animals could look after themselves there.92

Beatrice Elliott (née Bartleman) was 82 years old when I spoke to her in 2001. She described how the Tsartlip people used the land at Tod Inlet across from the ferry dock in Brentwood as hunting grounds, probably in the 1930s. There were grouse in the wooded areas. The Tsartlip also had land there as a place to take livestock when they left to go to the US or to the mainland to do seasonal work or to fish in the Fraser River—there was a good grazing area for horses. People lived on clams, hunted deer and shot pheasants and grouse. Beatrice remembers a group of people going up into Tod Inlet digging clams: “Everything was clean, the water was so clear.”

Manny Cooper and Marshall Harry also took their horses across Tod Inlet to the area opposite Butchart Cove. There was good pasture and lots of free water in the summer there. Harry took geese along with his horses.

In the early 1940s, the people from the Tsartlip Reserve still made their traditional trips in summer to Yakima, in Washington State, for the hop harvest. Everyone from Tsartlip to Duncan went to Yakima for the harvest. They picked blackberries first, then hops. There were five or six different camps: the Yakima people had their own camp, as did the Blackfoot. The Tsartlip people were part of what were known as the “BC Camps.” While Manny Cooper was away, “Old Man Chubb” (Fred Chubb, Robert Butchart’s chauffeur, who lived at Tod Inlet) kept an eye on the horses to make sure they didn’t swim back across. In September the Tsartlip people would come back to retrieve the horses.

The Thomson family of Brentwood also swam their cattle across Tod Inlet in the years around 1935 to let them graze on the south side of the inlet. If they drove the cattle in along Durrance Road, the cattle would simply walk out again, but if they were swum across, they would stay, grazing opposite Fernie Beach. Lorna Pugh recalled her dad, Lorne Thomson, leading the young stock not being milked, about 10 to 12 head, across by rowboat. On Sundays, the Thomson children rowed across to check on the cattle and have a picnic. Manny Cooper remembered working on Lorne Thomson’s farm for a dollar a day, cutting and baling hay for the livestock.

When the Tod Inlet plant shut down, many of the married men continued to live at Tod Inlet, working in the tile plant or at Bamberton. The population of Chinese workers, however, must have fallen rapidly. A few men continued to work at the inlet, in the tile plant or the gardens, but most of the 200 or so probably left by the 1930s. Unlike the white workers, the Chinese did not commute by boat to Bamberton. For the few that remained, a truck from the cement factory went to Victoria to pick up groceries in Chinatown in the 1930s. The store that supplied the provisions was Hang Ley’s, at the corner of Government Street and Herald Street. Lorna Pugh remembers selling perch to the few Chinese workers still living at Tod Inlet.

The old laundry house in 1966. Alex D. Gray photograph.

The first aerial photographs of Tod Inlet, taken in 1926, show at least four buildings still standing in the Chinese-Sikh village area. The field in the centre of the photo at left is where the company horses grazed. North of this is the row of white family housing and the entrance to the Butchart Gardens. South of the field is the Sikh and Chinese workers’ village. At the southwest corner of the field, near the mouth of Tod Creek, is the laundry house. To the southeast is the larger two-storey Chinese bunkhouse.

When Dem Carrier went up to the village to sell fish in the 1930s, there were still three houses on the north side of the road east of the stable, but only one on the south side. The large house visible in the 1926 air photo was no longer there.

The longest-standing building used by members of the Chinese community was the former laundry building at the edge of the hayfield. The Butcharts’ big house at the gardens had no place to do laundry; the basement was low and was heated with radiators, and so unsuitable for drying laundry inside. As former gardener Pat van Adrichem recalled, “There is no way Mrs. Butchart was going to hang out sheets.” The laundry building at the Chinese village was built by the Butcharts, probably in the early 1900s, and all their laundry was sent down there to be done. The laundry workers, almost certainly Chinese, used a big water boiler to “cook” the sheets. As there was no electricity, irons were heated on the stove. The working area included a smaller room at the back of the house with two larger chimneys.

At some point a two-inch pipe was put in for a waterline to the laundry house from the fire hydrant at the intersection of the two paths in what was the Chinese village. This pipe can still be traced from the fire hydrant at the main road junction to where the house stood. The position of the fire hydrants is marked on the 1916 map of the cement company structures.

Yat Tong, who came to Tod Inlet in 1912, lived in the old laundry house with another man in the 1940s—the only residents in what was once a bustling village of hundreds of immigrants from China. At first Tong lived in a bunkhouse with 30 other Chinese labourers. Later, he moved to the former laundry house with another gardener, Bing Choy, who joined the gardens in 1941.

Former gardener Pat van Adrichem worked with Tong and got to know him well, learning at least a part of his story. When Tong was delegated by Robert Butchart to work in the gardens on one or two days a week, his work apparently impressed Mrs. Butchart. From an interview in the Islander in 1961, we can almost hear the only words directly from Tong that have survived. In his own description of how he came to work at the Butchart Gardens full-time:

Missy say to me, “Tong, you like work here allatime?”

I say, “yes.”

Missy say, “I see Missiter.”

Next day, Missy say, “Al’ight, Tong. You work here allatime.”93

The transcription may seem like an uncomfortable stereotype, but the piece reflects the way the speech of Chinese labourers was perceived at the time. Tong’s English was clearly sufficient to communicate with his employers.

Allan Ferguson was a shift worker at Bamberton from 1947 to 1954. The Ferguson family lived in the house at the top of the row of company dwellings at Tod Inlet. The house was freezing cold, with no basement. His wife remembers the three Chinese men who worked at the gardens: Tong, Choy and Wing. She recalls that they “got on great” and were good to the kids of the village. Although Tong and Choy lived in the same house—the laundry house, in the field—she never saw them talking to each other and always saw them walking one behind the other. One was from Guangzhou, then called Canton by westerners; the other from Beijing (Peking). Wing lived in the bunkhouse. He was older and had been there longer. He left before Tong and Choy, retiring in 1949 or 1950. Mrs. Ferguson remembers Tong as more outgoing and generous. The kids loved them. The two men always brought treats for the kids after a Saturday’s bus trip to Victoria’s Chinatown.

The fire hydrant and the shut-off valve in the Chinese village area, 2019. David R. Gray photograph.

Glazed ginger pots found at Tod Inlet. David R. Gray photograph.

Joyce Jacobson (neé Carrier), who was born at Tod Inlet in 1921, remembers that the Chinese men lived in about four houses, arranged in a semicircle, of which she never saw the interiors. Choy and Tong worked with her dad at the cement tile plant. When they finished work, they walked up the road past the village. Jacobson would watch for them and run up from the beach and sell them perch or cod at 5 cents (75 cents in 2020) each, or even 15 cents ($2.25) for large perch. She recalls that they “were nice guys to us.” At Chinese New Year, the men who worked with James Carrier at the tile plant would bring the family a gunny sack of dried lychee nuts and green-glazed jars of sugar-syrup ginger, and a silk handkerchief for Mrs. Carrier.

With more and more visitors now coming to the gardens by car, the Butcharts decided to improve the old Lime Kiln Road to Tod Inlet. The route was smoothed out by eliminating a few corners east of Wallace Drive and rounding off the major curve just north of the present entrance to the gardens. The remnants of the former roadbed can still be seen on both sides of the road east of Wallace Drive and on the inner (east) side of the curve near the gardens. The roadbed was newly constructed, and the road was surfaced with cement in 1929. In the same year, it was renamed Benvenuto (“welcome” in Italian) Avenue, reflecting the name of the Butcharts’ residence, and their famous welcome.

It is interesting that this project was an early demonstration of the use of cement for road surfacing. In a company ad in the Nanaimo Free Press, the BC Cement Company declared, “Concrete Roads surpass all others. They save public time and public money. They are always safe to drive on, and are permanent investments. It pays to have the Best.”94

The Canadian Pacific Railway Company ran excursions from Vancouver to Butchart Gardens in the early 1930s. The CPR SS Princess Patricia left Vancouver at 10 a.m. and started the return journey from the Tod Inlet wharf at 4 p.m. “One of the most enchanting beauty spots on this continent, Butchart’s Gardens are visited by tourists from all parts of the world. You’ll enjoy every minute of this scenic cruise to Tod Inlet, with a delightful visit to the Gardens,” ran an ad in the Vancouver Sun on July 20, 1932. The return fare was $2 ($30 in 2020 dollars), “children half fare.”

Excursion ship arriving in Tod Inlet for a tour of the Butchart Gardens. BC Archives F-04193.

Stern view of the cement ship Shean leaving the Tod Inlet dock. Carrier family collection.

Mrs. Butchart received the City of Victoria’s medal for Best Citizen in 1931 because she opened her gardens to visitors each day of the year. By then tens of thousands of people had visited Butchart Gardens. Maclean’s magazine described it that year as “more than 20 acres in which every flower and shrub of the temperate zone grow at their best: where anyone at their leisure could wander without encountering a ‘Keep off the grass’ or a ‘Do not pick the Flowers’ sign.”

With the increased production of cement at Bamberton, the company ships Teco and Matsqui could no longer handle the growing transport requirements up and down the coast. Consequently the company managers once again looked to Great Britain to augment the cement fleet. In 1924 they purchased the coaster Fullagar. She was built by the Cammell Laird shipyard in Birkenhead, the first shipyard in Great Britain to use electric arc welding. When Fullagar was launched in February 1920, she was the world’s first all-welded cargo ship. She was 150 feet long, with a gross tonnage of 398. Renamed Shean, the new company ship crossed the Atlantic, traversed the Panama Canal, and arrived in Victoria in good condition. She replaced Matsqui to join Teco in the cement trade, mainly carrying cement to Vancouver. Matsqui was sold to the Coast Steamship Company of Vancouver in November 1924. She ended her career as a barge for a fishing company in the early 1960s.

The new cement ship Shean in Tod Inlet. Author’s collection, from BCCC photo album.

But again the output of Bamberton cement surpassed the capacity of the ships in use, and again, in 1928, the directors of the BC Cement Company sent word to their United Kingdom representative to look for another ship. A year later the company purchased the Granit, built in Norway in 1920. She was 166 feet long and carried one ton in her hold. Renamed the Island King, she began her eventful career on the west coast with an adventurous voyage across the Atlantic and into the Pacific—a trip that lasted an incredible nine months! The journey included a minor mishap on leaving port, a three-day stranding off the coast of Kent, continuous engine trouble, months of delay in the Azores, where an engineer and some of the crew quit, the death and burial at sea of the second engineer, a 25-day drift without engines, adjustments to the engine in the Virgin Islands, and another change in crew. She finally made it safely into the Pacific Ocean and up the coast to Victoria. Shean was summoned to tow Island King to Bamberton, where her cargo of gypsum from Rouen, France, was off-loaded. Shean then towed Island King back to Victoria, where a new Union engine was installed at Yarrows Shipyards.

Aerial views of Tod Inlet showing the plant, office buildings, bunkhouse and company housing, 1930. In the two photos on the right, you can see the Butchart Gardens in the background. In the top two photos, you can see the Island King at the wharf. In the left photo, the road to the Chinese village and the trail to the laundry house can be seen on the right. For a detailed map, see here. National Air Photo Library.

In 1930 Shean hit a rock off Victoria at full speed and shattered her forepeak bulkhead. The welded plates of her hull held, though severely buckled. Only 400 bags of her cargo of 10,000 bags of cement were damaged, and Shean made port under her own power.

At various times during the Depression, one or another of the cement boats—Shean, Teco and Island King—were taken out of service due to lack of work. When not in use, they were tied up at the wharf in Tod Inlet. Bob and Alice Guisbourne lived aboard as caretakers. Joyce Andrews, who lived at Tod Inlet, used to go down to visit the Guisbournes, make fudge and dance to the radio.

Teco and Shean were seen periodically in Tod Inlet until the mid-1930s, and Island King probably up until 1944, as the ships were occasionally called to deliver cement to the tile plant. In later years of operations, Teco also picked up cement tiles and flower pots from Tod Inlet. Her captain, mate and crew of six (the chief and second engineers, a winchman, two deckhands and a cook) remained the same during this period, but their monthly wages dropped dramatically as a sign of the hard times. The mate’s wage dropped from $142.50 to $80, and the chief engineer’s from $205 to $100. Teco’s cook, Quon Don, earned $75 a month in 1926 (equal to $1,115 in 2020 dollars), but nine years later his wages had dropped to only $45 (equal to $855 in 2020 dollars). By 1936, the last known year of ownership by the BC Cement Company, only the master, Captain Hunter, lived at Tod Inlet.

Dem Carrier near the mouth of Tod Creek with a company scow in the background. Carrier family collection.

Remnants of the large cement tiles used to form the grids on the mud flats near the mouth of Tod Creek. David R. Gray photograph.

After the other ships were sold—Matsqui in 1924, Shean in 1935 and Teco in 1936—Island King continued loading cement at Bamberton. By 1944, when the Island King was sold, cement was already being shipped by tugboats pulling scows (barges), or by larger ocean-going freighters not owned by the company.

To make the cleaning and painting of the BC Cement Company scows easier, a system of “grids” was placed on the tidal flats at the east end of Tod Inlet between 1930 and 1940. A series of 14-inch-long cement tiles, two stacked upright and filled with concrete, were placed in a grid pattern to support the scows, which were manoeuvred into place at high tide, then allowed to settle onto these short pillars as the tide went out.

The tiles were placed about one metre apart, allowing the men and boys hired by the company to crawl underneath and scrape barnacles, mussels and algal growth from the undersides of the company barges, a job described by Dem Carrier as “simply terrible.” In later years he found the grids were a good place to collect pile worms for fishing bait. The grids show up on aerial photos of the time, and some broken tiles can still be seen there at low tide.

HMCS Armentieres. BC Archives A-00213.

The story of Tod Inlet saw yet another twist when the inlet was the site of an extensive military practice manoeuvre involving the Royal Canadian Air Force, navy and army. On the night of June 30, 1932, the 600 “attacking” troops from Vancouver were embarked on the warships HMCS Skeena, HMCS Vancouver and HMCS Armentieres, and landed in the early morning at Tod Inlet. The 800 “defending” troops were local military units camped at the Heal’s Range, just south of Tod Inlet.95

As the two forces engaged in mock battle, two aircraft from the Vancouver air station arrived to take part in the training: a Fairchild on floats and a Vickers Vedette, a small wooden flying boat. These aircraft were likely the first aircraft to land in Tod Inlet, and among the few ever to do so.

Vedette wooden flying boat, 1930. This is the type of aircraft from which the 1930 aerial photographs of Tod Inlet were taken. The pilots flew on training missions from the Royal Canadian Air Force station at Jericho Beach near Vancouver. Author’s collection.

In the Vedette was Flying Officer Costello, on the defenders’ side. He located the landing party in Tod Inlet and dropped information to the headquarters of the defending troops using the World War I–style message bags. Noting the three naval ships steaming north after landing the troops, Costello landed the Vedette in Tod Inlet twice to discuss the operation with the military observer. After patrolling the area of the operations, he noted it was “difficult to distinguish attacking troops from defending troops. Practically all movements were along roads.”96

In support of the attacking force, Squadron Leader Shearer flew the Fairchild to Tod Inlet with a signaller and an observer. They located the attacking battalion’s headquarters, sent messages with an Aldis signalling lamp, dropped message bags, made an attack on an “enemy aircraft” and patrolled the area until the “battle” was over and all the troops were marching to their training camp at Heal’s Range. After returning to their temporary base at Esquimalt, both pilots made additional flights to Tod Inlet carrying militia officers who wanted to view the battleground.

At some point in the late 1930s, just before World War II, the remaining kilns and all other large iron fittings were stripped out of the Tod Inlet cement plant as scrap iron and put on barges bound for Japan. Clarence Sluggett (Claude’s brother), who probably watched the proceedings from the tile plant, commented at the time, “It will all be coming back to us as bullets pretty soon.”

Japan had been a major buyer of scrap metal in the US and in Canada in the years leading up to the start of World War II. Japanese freighters loaded cargoes of scrap metal in Victoria in 1935 and 1937. When Japan invaded China in 1937, Canadians expressed their dismay that Canada would continue to allow Japan to buy scrap iron, copper and other metals that were obviously important to Japan’s military needs. In Victoria, Chinese Canadians protested the shipping of metal to Japan. The Saanich council sent a resolution to Prime Minister King calling for an embargo on exports of scrap metal to aggressor nations in July 1939.

White and Chinese Victorians picketed truck operators trying to move scrap metal aboard a scow intended for Japan in August 1939, just a month before Canada declared war on Germany.