The Butchart family, left to right: Robert Butchart, daughter Jennie Ross, Jennie’s son Ian Ross, and Mrs. Jennie Butchart. Courtesy of the Butchart Gardens.

World War II had a relatively minor impact on Tod Inlet. The men working at Bamberton were kept on, as the military needed cement for coastal defences and other installations. Though they had some trouble finding staff during the war, the company was able to keep the plant in production.

At the Butchart Gardens, though, the impacts were more deeply felt. In 1939, the Butcharts presented ownership of the gardens to their grandson, Ian Ross, on the occasion of his 21st birthday. Ross enlisted in the Royal Canadian Navy at the beginning of the war, and the gardens did not flourish during his absence. At the end of the war he resigned his commission and decided to make the running of the gardens his full-time job.97

The Butchart family, left to right: Robert Butchart, daughter Jennie Ross, Jennie’s son Ian Ross, and Mrs. Jennie Butchart. Courtesy of the Butchart Gardens.

At Tod Inlet, part of the old system of taking clay from the clay pit by the upper quarry to the cement plant was brought back into service in order to meet increased demand. The clay deposit up at Wallace Drive was reactivated, and clay was once more sent down to what is now called the Old Mill. An old metal skip still at the site was probably used for scraping and loading the clay. At the mill, the clay was mixed with water, then piped down to the old plant through a wood and wire pipe system. At the plant, they pumped the clay mixture into a barge at the wharf for shipment to Bamberton.

Map of Tod Inlet in 1935 showing the quarries (in blue) at the Butchart Gardens and the clay works and upper quarry at Wallace Drive. Department of National Defence, Geographical Section, No. 415. Author’s collection.

The trial run for this new endeavour didn’t pan out as expected. Because of the vibration of the tug’s engines, transmitted through the taut tow line to the barge, the clay settled out, and by the time it reached Bamberton, they couldn’t pump it out as planned. The men had to drill and dig it out, it had settled so hard.

When Bamberton started running out of limestone on the main mill site, they opened a new quarry at Cobble Hill, and later, in the mid-1940s, brought limestone in from the Blubber Bay quarry on Texada Island, north of Nanaimo. The BC Cement Company was one of three companies then quarrying limestone on Texada.

On June 16, 1944, the Vancouver Province reported that there was a large increase in demand for lime, for both war-related industries and agricultural needs. However, with the wartime shortages of manpower, lime plants were unable to operate at maximum capacity. Anticipating the future expansion of the British Columbia lime industry, the Roche Harbor Lime Company, based on San Juan Island in Washington State, established a new company and bought the lime works at Eagle Bay on Texada Island. The new company was called the McMillin Lime and Mining Company, and it had its headquarters in Vancouver. It was headed by Paul McMillin of Roche Harbor, son of Robert Butchart’s old acquaintance and competitor, John McMillin.

The remnants of the old clay mill, 2019. David R. Gray photograph.

Kangaroo at Tod Inlet. Alex D. Gray photograph.

As far back as the 1930s, cement company workers and others had kept their private pleasure boats moored in the inlet. Sir Frank S. Barnard, lieutenant-governor of BC from 1914 to 1919 and a friend of Robert Butchart’s, kept his 67-foot yacht Quenca in Tod Inlet at least until 1935. The big yacht was housed in a large boathouse that was kept in place by piles driven into the sea bottom. At least part of the flotation system supporting Quenca’s boathouse was large cement pontoons made at Tod Inlet around 1915. One of the pontoons is still lying on the beach below the village site, partially filled with mud. (Incidentally, my family’s connection to Tod Inlet started when my dad, Alex Gray, a Victoria resident and shipwright, became an occasional deckhand on Quenca.)

The 40-foot Kangaroo, built in Nanaimo in 1914 and owned by dentist Dr. Sam Youlden (“Doc Youlden”), first came to Tod Inlet in 1930. A small white wooden boathouse with red trim was towed to Tod Inlet from Victoria by the Kangaroo in July 1936. The boathouse was a centre of activity in summer for picnics, fishing and swimming, as well as a storehouse for rowboats and boating equipment.

Our family boat, Squakquoi, a 25-foot cabin cruiser launched at Portage Inlet in 1939, joined the group in 1941 after a few short stays in 1940. Squakquoi is probably derived from the word S₭O₭I,—meaning “dead” in SENĆOŦEN, the Saanich language. The name comes from my dad’s friends joking about how long it was taking him to build the boat. They said that the original wood in her hull would have dry rot before he finished building the rest. Dad wanted a First Nations name for his boat, and “Squakquoi” was the closest translation he could find for the term “dry rot.”

By March 1942, all of the Canadian Navy’s corvettes and armed merchant cruisers stationed on the Pacific coast had been diverted either to Alaska, because of the threat of Japanese invasion there, or to the Atlantic for convoy duty. To replace them, the navy organized the civilian Power Boat Squadrons (PBS) to fulfill a need for surveillance and protection of the British Columbia coast. More than 200 civilian boats, based in marinas from Victoria to Courtenay, began training with the navy, army and air force. British Columbians were concerned about a possible Japanese invasion, and the PBS had to be trained to respond. Simulated air attacks and beach landings in the dark of night prepared the squadron members for possible action.98

PBS137 Squakquoi in her war colours, 1942. Alex D. Gray photographs.

At least four of the private boats moored at Tod Inlet became active members of the local Power Boat Squadron: Dennis, Kangaroo, Squakquoi and Tum Tum. Along with the other 223 boats in the volunteer squadrons, the Tod Inlet boats were painted dark grey, with their individual PBS numbers in large white digits on the bow. In September 1942 the squadron practised with the Royal Canadian Air Force, which made mock attacks and dropped smoke bombs. In November, the squadron practised various manoeuvres outside the Victoria Harbour breakwater. Squakquoi was moored at Tod Inlet and Shoal Harbour during the war, depending on where the Power Boat Squadrons were sent for exercises.

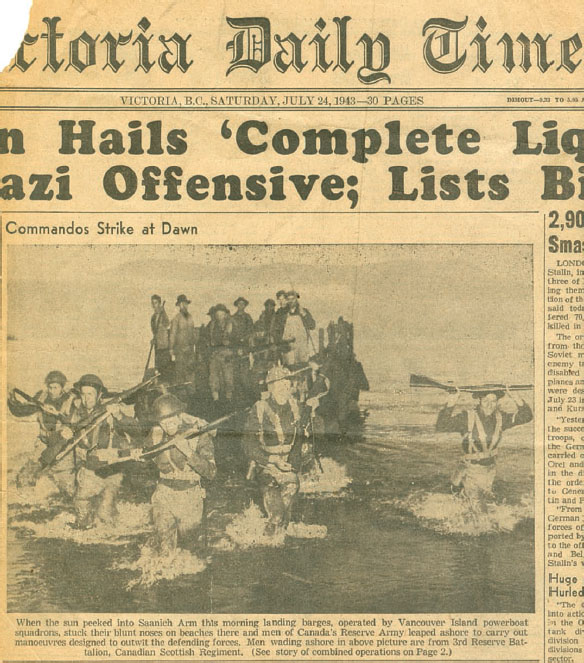

One of the squadron’s most challenging exercises was the nighttime transport of troops during a simulated invasion of Vancouver Island. In July 1943, the PBS, including the four Tod Inlet members of the fleet, the Royal Canadian Navy, the Royal Canadian Air Force, and the Home Defence Forces, prepared for a possible invasion. In the evening darkness, the boats left Deep Cove, in North Saanich, loaded the infantry troops of the attacking landing parties and proceeded to Brentwood and Tod Inlet. There the troops leapt ashore at dawn to engage the defending forces.

It was the most realistic operational maneuver, simulating real warfare, ever engaged in by these units, whose men are preparing themselves to defend these shores…. A fleet of grey-painted, numbered boats made a rendezvous overnight at a well-known cove. At 3 a.m. today, blacked out, they slipped quietly away and crossed to the point where the invading troops … were embarked…. At 5 a.m. the boats ran for the beach and just as dawn was breaking the first landings were made…. Waist high into cold waters the men jumped … rifles held aloft, full kit on their backs. Dripping wet they crouched along the beaches awaiting the order to attack …

Along the barnacled rocks and over clam shells the men crept cautiously beneath protecting trees and up the banks, where they took up firing positions to engage the enemy, entrenched behind barns and fences…. By sun up the battle was in full swing…. On stretchers the “wounded” were packed through heavy underbrush and down sloping banks to dressing stations. Before the battle ended the troops were subjected to gas attack.

Following the maneuver the powerboats returned to their regular anchorages and the soldiers marched to their Heal’s camp.99

Alex Gray’s Power Boat Squadron’s badges and membership cards. Author’s collection.

The landing of troops during a PBS manoeuvre in 1943. Victoria Daily Times, July 24, 1943. Author’s collection.

Four of the powerboats were already home.

With the passing of the immediate threat, the pressure on the PBS decreased, and by the end of the war, the squadrons had been disbanded. The nucleus of one squadron, however, the North Saanich Squadron at Deep Cove, was preserved. This became the starting point for a civilian yacht club promoting training in good seamanship. In 1947, the squadron became the Capital City Yacht Club. Today, the Canadian Power and Sail Squadrons, an organization of recreational boaters with over 20,000 active members, continues the legacy of the PBS throughout Canada.100

In 1946 the Tod Inlet Power Boat Owners’ Association was formed by the small group of boaters who still moored their pleasure craft at Tod Inlet. The objectives of the association were to improve the conditions for boat owners mooring in the inlet and to provide proper landing facilities. At the start there were 29 active members. In later years the number of regular members was kept at 34 to avoid overcrowding. Fred Chubb, who lived at Tod Inlet and had worked at the cement plant in the early days, before becoming Butchart’s chauffeur and later the engineer of the Bamberton, was appointed honorary port warden.

The objectives of the association were simple: “to install, operate, maintain and repair docks, wharves, floats, gangways, marine ways, mooring buoys, and similar facilities for the mooring, docking, repairing, maintaining, and servicing of boats owned and operated by members.”101

Alex Gray’s membership card for the Tod Inlet Power Boat Owners’ Association. Author’s collection. David R. Gray photograph.

David Gray with his grandparents John and Edith Gray at the Tod Inlet boathouse. Alex D. Gray photograph.

Three Gray children on Squakquoi in 1948. Alex D. Gray photograph.

The Gray children playing in a rowboat at the boathouse, 1947. Alex D. Gray photograph.

My own early involvement with Tod Inlet also began in 1946. At seven months old, I experienced my first trip on our family boat, Squakquoi. My mother recorded my reaction in a baby book: apparently I “just loved the water, couldn’t keep [my] eyes off it.”

That year the association also began building a wharf and small marine railway, known as “the ways,” for hauling out boats. Tom Ward, owner of Tarpon and vice-president of the association, talked directly to Nigel Tomlin, president of the BC Cement Company, who agreed to supply the cement for the construction of the ways, though many of the club members thought it was a bad idea to be indebted to the company.

Often working at night using floodlights to take advantage of low tides, the members expended about 2,000 man-hours under Tom Ward, the acting construction engineer. The ways were probably finished in early 1947, as the date “Feb 16 1947” is inscribed in the cement foundation. The ways used a unique system of chains and plates to support a boat and adjust its position as it was hauled up out of the water on the rails and held in a wooden cradle. The lower part of each chain was sheathed in rubber tubing to protect the boat’s hull. The supporting chains on each side fitted into the holed and grooved plates at the top of the wooden side posts of the cradle. They could be adjusted as the boat on the cradle was winched up out of the water. The ways could take boats up to 65 feet long and weighing up to 35 tons. They were still in use in the 1970s.

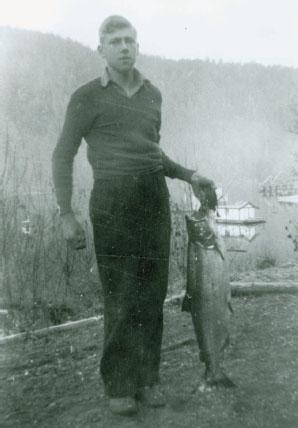

The annual Tod Inlet fishing derby, started in 1948, was popular with the community of Tod Inlet as well as with the members of the association. There were prizes for the largest and smallest fish, and plentiful cake and green fish candy as treats for the children. The winning fish were described as “small” in the second annual derby in 1949: the first-prize fish weighed only 10 pounds.

The black can buoy moored close to a rock on the eastern side of Tod Inlet was a popular spot to fish for lingcod in the 1950s. As a family, one of our favourite weekend outings was to go with Doc Youlden on the Kangaroo to tie up to the buoy and fish for cod. We would lower our lines, baited with small live pile perch that we had caught back at the wharf, and watch them sink. It was thrilling to see the lingcod moving below through the clear green water—though I don’t remember much success at catching them.

I well remember the exciting summer activity of fishing for the big striped sea perch that lived under the boat dock. The only way we could catch them was by dropping a hook, baited with small mussels, through a knothole in the planks of the wharf. When a perch got hooked, you dropped your line that was attached to a dowel of wood through the knothole, then dove under the wharf, swam up to the surface under the dock, retrieved the dowel and the line, then swam back out from under the wharf to emerge triumphantly with the fish.

My personal memories of this unique time at Tod Inlet are powerful. There was a great sense of camaraderie amongst the boat owners—and an inappropriate sense of ownership of the inlet, at least among the children. But it was a playground unimagined by most: the water perfect for swimming and fishing, the fun of meals aboard the boat, the other families, and of heading out for summer adventures in Saanich Arm and the Gulf Islands. There was also the excitement when a big racing canoe from Tsartlip came into the inlet.

Squakquoi on the ways at Tod Inlet, 1948. Note in the left background the clear-cut logging on the hill south of Tod Creek and the log dump, and the logging road running up towards the Partridge Hills. Alex D. Gray photograph.

The Tod Inlet anchorage in 1947. Author’s collection.

Members of the Tod Inlet Power Boat Owners’ Association who worked on building the ship ways in 1947. Author’s collection.

Children with dogfish shark, with the tile plant and ship ways behind, 1954. Alex D. Gray photograph.

The dock decorated for the annual fishing derby, early 1950s. Alex D. Gray photograph.

Boys on Squakquoi, about 1960. David R. Gray photograph.

The long tradition of people from Tsartlip using Tod Inlet to train for canoe races continued into the 1940s. Ivan Morris recalled that the most common training course was from Tsartlip Reserve to Tod Inlet and back. Ivan was part of the crew of the well-known racing canoe Saanich #8. When he started going to Tod Inlet, the cement plant was already abandoned and falling apart. They saw the buildings, and the boats tied up there, but never saw the plant in operation.

People at Tsartlip who made dugout canoes included Marshal Harry, Philip Tom and Tommy Paul. Harry worked on both racing and other canoes. He made one of the best, and best-known, racing canoes: Saanich #5. Beatrice Elliott’s dad, Joe Bartleman, paddled in that canoe. “They won so many races in that canoe,” Beatrice recalls. “I remember as a girl the practices before the races, when everyone went to the beach. Afterwards, the paddlers were served lime cordial or lemonade from a big bucket. The canoes were taken by gas boats to races on the coast or by truck to the races at the gorge.”

Canoe race at the Tsartlip Reserve, Brentwood, May 1965. Alex D. Gray photograph.

After the canoe races at the Tsartlip Reserve, May 1965. Alex D. Gray photograph.

On the opposite side of Tod Inlet from the cement plant and village, there was little or no industrial activity into the 1940s. The forested hills leading up into the Partridge Hills maintained their quiet stillness in spite of the commercial activity facing them. The people from the Tsartlip First Nation at Brentwood, just around the corner, were the primary users of this forested land. They continued using the land for traditional hunting, fishing and trapping, as well as for the grazing of livestock, well into the 1950s.

After the war, all the timber rights to the forested land around Tod Inlet were sold by BC Cement to logging companies. As Dave Elliott Sr. recalled in 1983, “We knew it was our land, we never had any other thought but that it was our land.” But “we lost the land somehow. One after the other—land, fishing rights, hunting rights were legislated away…. The treaty with James Douglas said we could hunt and fish as formerly. We can’t.”

Although the Douglas Treaties had stated the Indigenous people could keep their “village sites and enclosed fields,” as well as the right to fish and hunt in traditional territories, in reality they were denied these rights by the practice of the government selling all lands outside of the reserves, which the government itself had designated.

The Tsartlip people continued to hunt on the Partridge Hills, the high land above Tod Inlet, throughout the 20th century, as their ancestors had for hundreds, perhaps thousands, of years.

When Ivan Morris was born, his family lived in a longhouse on the Tsartlip Reserve with fire and no electricity. At the age of 13, Ivan would go hunting about three times a week up in the Partridge Hills above Tod Inlet to get food for the table. They would take three deer a day, sometimes, to feed the community.

In an interview in 2001, Ivan explained to me that “at that time, the law at Tsartlip was that whenever the head of the family went out hunting, no one was to play around. Just sit still, not even wash the dishes. The law of the Elders was to do nothing until the hunters returned home.” When Ivan and his older brother went hunting, his younger brother had to keep still in the home. “We always went by canoe to the mountain, pulling up on a patch of gravel at the end of Tod Inlet walking up into the hills, though we never got many deer there. There was always a great feeling when we got home. The family was always happy that there was food on the table.”

John Sampson (1945–2014), a respected Tsartlip Elder, also shared his memories of Tod Inlet with me in 2001. John and his family used to dig clams up at the end of the inlet. He would row to “the red house” on the west side of the inlet narrows and go hunting all day long up as far as Durrance Lake. That was in about 1958, after the logging. “As kids we used to go through the old cement plant, play around the area and swim in the inlet. Sometimes we saw smoke from the plant. White people used to scare us off the property, but later we made friends with other boys from Tod Inlet, and then we didn’t worry about being chased off.” Tod Inlet was the only place they could go to hunt because they had no car—or they could go to the Goldstream Reserve by canoe. People often hunted along the shore from the canoe.

Tsartlip Elder John Sampson during an interview in 2001. David R. Gray photograph.

John also remembered when the white families who moved into houses up there (near Willis Point) kicked his dad and others off of the mountain. Even though they protested that they knew how much to take and how much to leave, they still were not allowed to use the area—this was not an issue of conservation but an issue of perceived ownership and possession.

Even after their rights to use the traditional lands were denied, Manny Cooper hunted all through the hills around Tod Inlet, starting when he was 12 years old (about 1940; he was born in 1928). He hunted from the mouth of the inlet over the hills to McKenzie Bight on Saanich Arm. There the salal was thick and grew as tall as your head.

Deer eat the leaves and berries of the salal, and Manny also believes the leaves are medicinal for deer. Once, at Sheppard Point, on the west side of Saanich Arm, Manny shot and wounded a deer, pulled his canoe up on the beach, then followed the deer as it took off. He watched the deer eat salal leaves, chew them and put the chewed leaves into the wound. There was no more blood, and Manny was not able to catch up to the deer.

Manny was active in trying to get some compensation for the loss of traditional hunting territory around Tod Inlet. The change in hunting patterns has been drastic: in the days before logging they used to get a deer after walking only about 250 metres from the beach; and then they had to travel down to McKenzie Bight; and now they cannot hunt at all in the area.

The Tsartlip name for Tod Inlet, which translates as “Place of the Blue Grouse,” indicates the importance of these birds. Tsartlip Elder John Elliott (STOLȻEȽ) talks about the historic relationship between the Tsartlip and the blue grouse on the FirstVoices’ SENĆOŦEN website, which is dedicated to the teaching and learning of the SENĆOŦEN language. “Our Saanich ancestors could go out to gather the Blue Grouse just with a basket and a stick; because there was so many that they had become tame and wouldn’t even fly away. Plentiful amount of Blue Grouse is a sign of a healthy environment.”102 At the time of the Bullhead Moon, SX̱ÁNEȽ (April–May), the almost full-grown grouse could be snared in the woods. A review of the history of this species in the area helps in understanding how that importance has changed over the years. Hunting of blue grouse was an important fall activity for many hunters in the early 1900s. The Victoria Daily Times reported on September 10, 1903, that special trains were run on Labour Day by the Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway to pick up hunters at the various stations south of Shawnigan. The reporter noted that there were many hunters with grouse in their bags, from two or three up to thirty.

Male blue grouse, in courtship display. SD MacDonald photograph. Canadian Museum of Nature Archives S95-22599 TG C55.

The Vancouver Island Fish and Game Club was active in 1904 and 1905 in getting amendments to the Game Act to help protect the blue grouse. By 1905 the sale of game shot on Vancouver Island was prohibited, but the club was still urging the appointment of a special constable to patrol the districts near Victoria where blue grouse were being “sold in numbers” out of season.103

In another twist to the blue grouse story, Hungarian partridges (also called grey partridge) were released near the cement works at Tod Inlet in the spring of 1908. (They may have had an impact on the decline of the blue grouse.) By November, partridges had been seen near the cement plant, on Keating Cross Road, and in the Highlands on the west side of Tod Inlet.104 This and other introductions in southern BC were not successful, and the grey partridge populations died out between the 1930s and early 1970s.

The suggested open season for blue grouse in the 1920s extended from early October to mid-November, and the bag limit was still 6 birds per day and 50 birds per season. By 1925, the open season for the area including Tod Inlet area had been reduced to the last two weeks of September.105 The blue grouse hunting season for Vancouver Island currently extends from September 1 to December 31 with a daily bag limit of 5 birds (15 for the season).

Since 1970 blue grouse populations have declined, probably because of urban development. The current status of the blue grouse around Tod Inlet is unknown. I have never seen a grouse at Tod Inlet, even when exploring the Partridge Hills.

Ornithologists decided in 2004 that what we have called the blue grouse is actually two closely related species, now named the dusky grouse and the sooty grouse. It is the sooty grouse that lives on Vancouver Island and in the Tod Inlet area.

Tod Inlet was also known for lots of blue grouse. Cooper used to hunt them with a .22-calibre rifle. He loved fried grouse, and still hunted them into the 2000s.

John Sampson’s grandmother Christine Pelkey and her husband, Philip Pelkey, used to trap mink and otter around Tod Inlet, up to the Goldstream Reserve in the 1920s and ’30s. They trapped whatever people would buy and took the pelts to Vancouver to sell. They had a 20- or 25-foot dugout canoe that carried all their trapping and camping gear, including canvas for a tent and a pole to hold up a sail. John remembered his whole family going clam digging with them. When he was young and travelling by canoe, he was told, “Sit and don’t move.”

In the late 1930s or early 1940s, the Tsartlip people still followed their tradition of cutting cedar boughs during the herring run in March and placing them in the water. When the boughs were covered with herring spawn, they would strip the spawn from them to eat.

Around the same time, people from the Tsartlip Reserve would also come into the inlet during the herring run in one-man canoes and troll for spring salmon using 50-foot linen lines. Manny Cooper remembered going in with canoes and fishing for big spring salmon with a two-fathom line tied to his leg, using #4 or #5 Canadian Wonder spoons. They used abalone spoons for grilse and also speared lots of cod from the rocks.

Dem Carrier, as a young white fisherman in the 1940s, was intrigued by the almost magical success of the Tsartlip people. Was it due to some special local lure or bait? He was surprised to learn some years later that they used the standard Martin white-red gill plug, available from any fishing outlet!

In 2001 Beatrice Elliott told me about her husband’s (Tsartlip Elder Dave Elliott Sr.) love for fishing: “David used to go fishing in Tod Inlet, where there was always good fishing. He used to go up there during the war. He netted small pilchards to use as bait for other fish. He caught dogfish in Brentwood Bay and took the livers to Ogden Point, where someone bought them for the oil. While fishing, he would line up different points to locate his fishing area for dogfish. He also caught lingcod and rock cod, and always gave fish away to people. He was a fisherman all of his life, until he couldn’t fish because of his health.”

Beatrice also remembered going to Tod Inlet in a canoe with Elder Genevieve Latasse, who took her up to the Butchart Gardens. Her eldest brother also took her out in a canoe and speared cod with a long spear.

John Sampson’s great-grandmother Lucy Sampson, who died at the age of 106 in 1980, told him of seeing killer whales in the inlet. There was a pod of orcas known as the Seven Sisters who used to come into Saanich Inlet in the late 1950s, when John was about 13. The whales never bothered anyone, but when they were around, the younger guys were not allowed to go out fishing. As great-grandmother Lucy said emphatically, “There were others out there fishing!” She said the whales followed one at a time in and around at the mouth of Tod Inlet, along Willis Point and down to Mackenzie Bight.

Fishing spoons made of abalone shell. David R. Gray photograph.

Dem Carrier with a salmon in front of the Carrier house. Carrier family collection.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, John used to catch trout in Tod Creek and big grey perch at the ferry wharf. He would take a sackful of perch (about 20 fish) up along Wallace Drive to a Chinese man who lived on Durrance Road, who would buy the sack for two dollars. During this time John and his brother Chuck also speared cod behind Daphne Islet. John paddled while Chuck spotted the lingcod. He speared them with an eight-foot three-pointed spear made by his dad. John’s brother Ken used to make fancy spear points like arrowheads, but they were hard to get out of the cod. They used to leave their spears where they fished in case they ran into fisheries people. While fishing at night in Goldstream River, they sometimes had to leave their spears behind on the bank. They rowed the dugout, rather than paddling, when fishing for salmon so that one could easily handle the canoe while the other fished. The five-foot oars overlapped while rowing because the dugouts were only about three feet wide. They tied the fishing lines to their feet so they knew when a fish was on the line.

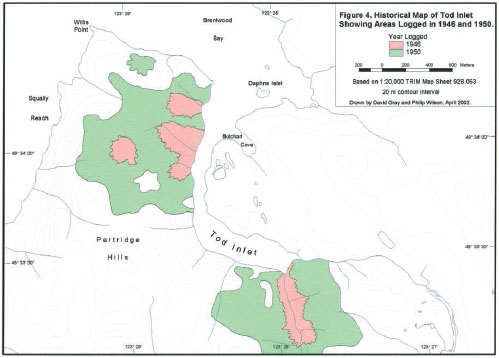

Map of areas of clear-cut logging around Tod Inlet, 1940s–1950s. Philip Wilson and David R. Gray.

A few large old stumps in the valley of Tod Creek provide evidence of the selective logging carried out in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Large notches in these stumps indicate that the trees were cut by two men standing on springboards and sawing with a two-man crosscut saw.

Several areas around Tod Inlet were logged by clear-cutting between the late 1930s and 1950s. In the mid-1940s, the Copley Brothers of Victoria logged the area south of Willis Point and on either side of the locally named Joylorn Creek, running down into the south corner of Tod Inlet. By 1946, three large areas on the west side of Tod Inlet had been logged, from the mouth of the inlet opposite Daphne Islet, southward to opposite Fernie Beach. Bob Copley recalled that they used a 24-foot boom boat, Logger Lady, for the log-booming operations in the early 1950s.

Aerial photo of the Butchart Gardens and the cement plant at Tod Inlet in 1956. Courtesy of the Butchart Gardens.

By 1950 the logged areas covered most of the west side of Tod Inlet from its mouth to its southwest corner, extending up over the Partridge Hills halfway to Saanich Arm. From the head of the inlet, the logging at Joylorn Creek had extended to the east, west and south, with logging roads leading to Durrance Lake.

While logging around Joylorn Creek, the company established a booming ground at the southeast corner of the inlet. They built a log dump on the inlet’s east shore, just south of the mouth of Tod Creek, placing large cedar logs at a near-vertical angle on the slope above the beach. I remember seeing the logging trucks dumping their logs into the inlet in the contained booming area in the mid-1950s.

Squakquoi at the boathouse, about 1960. Note the vertical logs of the log dump in the background, to the left. David R. Gray photograph.

Some of the Tod Inlet archaeological sites were damaged during the logging. The midden along the shore south of the creek was extensively damaged by the construction of logging roads, the log dump and the booming ground. As earth was bulldozed towards the sea, much of the central shell midden material was removed or redistributed towards its southern end.

Areas on the south side of Tod Inlet were also selectively logged. A logging road descended to the south shore of Tod Inlet opposite the cement plant’s wharf. Both fully loaded logging trucks and single bulldozers pulling log arches came down the rough road to dump their cargo into the water. The logs were held in a boom that extended west along the south shore. Logging at Tod Inlet must have been completed by the mid-1950s, because no booming grounds are visible in the 1955 or 1959 air photos.

The logging rights to the BC Cement Company lands on the east side of Tod Inlet up past Wallace Drive to West Saanich Road were held by the Selective Logging Company of Victoria, owned by Stan Neff and his brothers. They logged these areas between about 1945 and about 1956. Much of the operation was horse logging; trees were cut by hand, rolled down banks, and loaded by hand onto horse-drawn trailers. On steep hills they loaded the logs onto the trailer using skids on the side of the road. When coming down a steep hill, the driver stopped the horse when necessary by running the log it was pulling behind a stump. Selective Logging also operated two trucks, a tandem rig built out of a 1940-or-so Diamond T and an army truck, and a 1939 International single-axle truck with a trailer, formerly owned by Island Freight.

The company built a small sawmill on the west side of Wallace Drive, near its intersection with Benvenuto. They dumped logs into a small pond—Butchart’s flooded clay quarry. A jack ladder, a V-shaped trough with a spiked conveyor belt, pulled the logs up from the pond to the mill. Rough lumber was trucked from the mill into Victoria for planing at the company’s lumberyard on Douglas Street. Some was sawed for export and some for railway ties. The mill ran two shifts in summer, but shut down sometimes during fire season.

Workers at the sawmill in the 1950s included Rene Henderson, Woolly Smith and Tommy Paul from Tsartlip. John Sampson’s dad, Francis, and John’s oldest brother, Tom, also from Tsartlip, worked at this mill. The sawmill probably closed in about 1954.106

As the Tsartlip First Nation lost access to, and “ownership” of, Tod Inlet, the use of the area by settlers and other newcomers increased.

At Willis Point and south along the shores of Saanich Inlet, a whole new community was forming, at first of cottagers and summer residents, and later of permanent residents. Glen Twamley had purchased two sections of land in 1946, just before they were logged by the Copley Brothers. He later subdivided one into waterfront lots.107 This was the beginning of a permanent residency at Willis Point. The Rickinson family bought three properties in Smokehouse Bay and became the first permanent residents. The old Whittaker cabin still stood, until it was finally demolished in 1978.

At Tod Inlet, there were still a few people who could be described as farmers in the mid-20th century. One of them was Albert Cecil, the truck driver for the tile plant. Cecil kept horses for riding and pastured them in Yat Tong’s field, near the Tod Inlet Chinese village. He also kept cows in a pasture on the east side of Wallace Drive and ploughed two acres of land parallel to Benvenuto Avenue on the flats. He had a barn near the road (now a walking trail) up to the third quarry.

The three-room “larder” storehouse, still with its wooden roof, in 1979. David R. Gray photograph.

In about 1931 a huge fire burned over much of the area south of the intersection of Wallace Drive and Benvenuto Avenue, reaching almost to Cecil’s barn above Tod Creek. Dem Carrier remembers watching the treetops exploding during the fire. After the fire, Cecil grew potatoes on the burned-over land.

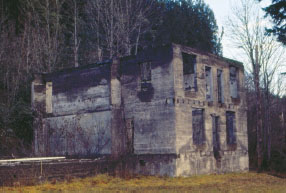

At one point in the 1940s, when housing in the village was scarce, Cecil lived in the tiny three-room larder or storehouse between the cement plant cookhouse and bunkhouse. With no connecting doorways, he had to go outside to move between rooms. This concrete storehouse is the only one of the cement plant buildings still standing.

During World War II, when sugar was rationed, James Carrier, who was foreman at the tile plant, tapped the local bigleaf maple trees and made maple syrup. The process required lots of sap and lots of boiling, as the sap was not as productive as the eastern sugar maples.

In the 1930s, settlers at Tod Inlet hunted deer and grouse in the land extending from the company barn through the burned-off area north to Wallace Drive. The construction of logging roads in the 1940s brought greater access to the backcountry, and there was more hunting in the hills around Tod Inlet. I remember in the 1950s the excitement of walking from the inlet up into the hills on the logging roads with adults who were “hunting.” We never left the roads, we never saw a deer and I suspect the guns were never loaded. For us hunting was just an excuse for an adventure, not an effort to put food on the table.

Bernard Woodhouse, who lived near Tod Inlet, held a trapping licence for the area in the 1930s. After him, Dem Carrier trapped mink all around the inlet and along Tod Creek. He also trapped muskrats on the upper part of Tod Creek, where it leads up to Durrance Lake. He remembers picking up salmon in Tod Creek and carrying them upstream, to help them reach their spawning area.

When the staff of the Butchart Gardens opened the dam on Tod Creek, cutthroat trout and bass from Prospect Lake would come out with the rush of water into Tod Creek below the dam. To catch the trout in the pool below the dam, Carrier and other young fishermen would splash water over the dam into the pool. The trout would only bite after there were waves in the pool from the splashed water. The children of Tod Inlet also regularly fished for large perch (probably striped sea perch) from the company or village wharf to sell to the Chinese workers. With their long working shifts, they probably appreciated the opportunity to buy fresh fish.

Claude Sluggett, born in 1909, grew up near Brentwood and saw the changes in abundance of Tod Inlet sea life. He remembered a run of pilchard into Tod Inlet one year when he was a kid, a run so large the fish piled up on the beach. Claude remembered when there were herring galore in Tod Inlet, and when people from Tsartlip came in dugout canoes to fish. But that came to an end.

Jim Gilbert of Brentwood Bay also witnessed great changes in the productivity of Saanich Inlet. Jim became a fishing guide in 1948 at the age of 13, working for his father, Harry, who had owned Gilbert’s Boathouse since 1927. As a guide and fisherman, he came to know Tod Inlet well. In his early days, Jim witnessed tremendous populations of herring coming in to spawn with the afternoon tides every April, followed by chinook salmon. The chinooks would move into the inlet at dusk and come back out in the early morning. When Jim was in high school, he and many others would go out in rowboats and dugout canoes to catch the salmon as they fed. He remembers how the Tsartlip Elders watched the diving ducks and noted the time they spent submerged to tell how deep the herring were, and thus how deep the salmon were.

And there were more than just fish in the inlet. Families in the cement company houses were woken in the night by the sounds of orcas splashing and blowing. On the smaller side, there were also littleneck and butter clams. The boys speared octopus, flounder and skate, and they fished for pile perch and lingcod off the old cement plant wharf, sometimes catching lingcod of 15 or 20 pounds.

Jim Gilbert’s dad, Harry, caught a 53-pound lingcod in the inlet when Jim was very young. In the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s, there was a tremendous population of cod and pile perch, and cutthroat trout of three or four pounds spawning up Tod Creek. Tod Inlet was a safe place for Jim and his friends growing up—Jim learned to swim there. As kids, they had seven-foot cedar rowboats that they could easily haul up on shore, and they hand-trolled Tod Inlet from the rowboats. In 1941, Jim and his sister, six and eight years old, caught eight- and ten-inch cutthroat trout with hook and worm.

In 1951, local fishermen notified Jim and his parents that there was a large shark in Tod Inlet. Wrongly assuming the shark was competing with them for salmon, they asked the Gilberts to catch it. The Gilberts went after it in an 18-foot boat, harpooned it, fired several rounds into it and looped the rope around a tree before they finally killed the shark. It was a five-metre-long basking shark, the largest ever caught in Saanich Inlet. There must have been substantial numbers of plankton in Tod Inlet for such a shark to feed.

Ivan Morris from the Tsartlip Nation also “used to see basking sharks, close to the beach here, huge things…. When kids started hitting them with rocks when close to shore, I stopped them.”

Basking sharks were common in British Columbia waters until the federal Fisheries Department began to actively encourage and participate in killing them. A fisheries patrol vessel chased and killed basking sharks by ramming them with a specially outfitted and sharpened bow. This eradication program killed at least hundreds, if not thousands, of basking sharks between 1945 and 1970, and the population has never recovered.

City directories for the years 1930–1945 list the “white” and mostly only the male population of Tod Inlet, with a maximum of 256 in 1940. This listing must have included men living at Bamberton—the directories had not yet caught up to the growth of the new community at the time.

The BC Directory (Victoria City and Vancouver Island) for 1950/51 shows a reduction of the population of Tod Inlet to 171 and lists 156 names, almost all men. Of the names listed, 123 worked for the BC Cement Company. Another 20 had jobs likely related to the plant (for example, “lab”), and five were gardeners. Three women were also listed: Phyllis Hamilton, A. Trowsse (“wid”) and Irma Trowsse, the latter a schoolteacher at Bamberton. Although women were listed in the census records, they were not usually listed in the directories.

When the Bamberton plant manager, Edwin Tomlin, died in 1944, the British Columbia Cement Company applied to become a corporate postmaster in his stead. James Carrier, manager of the tile plant, was the company-appointed postmaster in charge. He held that position from June 1944 until the post office closed in October 1952. Claude Sluggett was the postmaster’s assistant from 1939 to 1952.

The Vancouver Island Coach Lines bus service to Tod Inlet began with the Victoria–West Saanich route in the early 1930s. The buses also delivered the mail to Tod Inlet in the 1940s and 1950s. For the kids who came out to the inlet on weekends, there was always a bit of excitement when the Coach Lines bus came roaring down the road, around the sharp corner at the plant, and pulled up in front of the post office near the bunkhouse. The 1930s Coach Lines advertising colourfully described what we remembered of the 1950s buses: “A Streak of Orange … The Staccato Hum of the Exhaust, and It’s Gone!” For the villagers the bus meant mail or visitors; for us weekend kids, it was just a big, colourful, noisy attraction, as we didn’t see these big buses at home in Victoria.

When the post office was closed on October 8, 1952, the Tod Inlet & Victoria Mail Service became the Brentwood Bay & Victoria Mail Service, and the 1.1-kilometre route into Tod Inlet was deleted from the contract held by Vancouver Island Coach Lines. An extension to the mail courier’s “Route of Travel” from Brentwood Bay Post Office was requested to serve the 18 families who still lived within less than a kilometre of the former Tod Inlet Post Office. The heads of four of these families were employed at Butchart Gardens, and the remainder were employees of the BC Cement Company. Ron Tomlinson was living in the old company cookhouse, and Joe Hiquebran, carpenter for the company, was in the big house east of the vacant men’s bunkhouse.

The single men’s bunkhouse in 1965. David R. Gray photograph.

After being rebuilt at Victoria’s Point Hope shipyards in 1923, the Bamberton continued in the cement company’s service until 1952, when she was sold to a logging company. After that, workmen were transported from Tod Inlet to Bamberton in smaller boats hired by the company. Claude Sluggett operated such a boat between 1940 and 1950, carrying 15 people back and forth across Saanich Inlet, “a routine job with no problems.” In about 1950, the company bought the 25-foot Hunter, to transport some 20 employees from Tod Inlet to Bamberton. Hunter was built in about 1940 for Canadian Industries for the run to James Island. Claude operated Hunter between 1955 and 1965, then the company took it over. Hunter may have been named for the captain Hunter who captained the Teco for the cement company for many years.

Hunter at the wharf in Tod Inlet in 1979. David R. Gray photograph.

The last city directory entry for Tod Inlet appeared in 1952. After that, people living in the village were listed under the heading of Brentwood Bay. The directory for 1959 listed 14 households on Benvenuto Avenue below Wallace Drive. Among the names were still some familiar to people who grew up at Tod Inlet: van Adrichem and Shiner, who worked at the Butchart Gardens, and Tomlinson, Hiquebran, Rice and Ferguson, who all worked for BC Cement. Hiquebran was harbour master for the Tod Inlet boaters’ association between 1957 and 1963, though he was no longer living at Tod Inlet by 1961.

The company houses along the Tod Inlet road were all in good repair and occupied at least until 1958. After that, they were gradually abandoned. The last inhabitant was probably Evelyn Carrier. Her family negotiated with the BC Cement Company to allow her to stay in her house until she was unable to live alone, probably in the early 1960s. By then, even the Butcharts had moved to Victoria, when their declining health made living at Benvenuto more difficult. Robert Butchart died in Victoria 1943 and Jennie in 1950. Their ashes were scattered on the waters of Tod Inlet.

Squakquoi at the boat owners’ wharf in 1965. David R. Gray photograph.

The Gray family on their last trip to Squakquoi, 1965. Alex D. Gray photograph.

The boathouse beginning its last journey in 1965. Alex D. Gray photograph.

Treasures from the boathouse: an old ship’s lantern from the days of oil lamps, and a wine bottle full of varnish. David R. Gray photograph.

The village itself was finally abandoned, and the pleasure boats became the sole occupants of the port. The little wooden boathouse lasted until about 1965 when, more-than-somewhat waterlogged, it slowly sank into the inlet. One day just before it completely sank, my dad and I clambered gingerly in through the attic window as the water level reached that height and retrieved a ship’s lantern and an old wine bottle full of varnish. These were the only treasures we could reach to remind us of the structure’s 3o years of service to the boating families.

The last houses at Tod Inlet were destroyed by the local fire department during a training session in the 1970s.

We don’t know when or how the Chinese village was destroyed. The dwellings of the Chinese workers who left Tod Inlet in 1921 or so would have likely deteriorated fairly quickly, as they were not solid structures. Materials from the abandoned buildings may have been used by the few remaining Chinese residents to improve their own houses. When the Butchart Gardens began dumping compost, grass clippings and other materials over the banks of Tod Creek in the 1950s, most of the Chinese village was already gone.

However, a few crumbling remnants of the Chinese community at Tod Inlet still exist. The old “Chinese midden” keeps a silent record of who lived there and provides hints of what their lives might have been like. When my brother and I first discovered the numerous pig skulls there in the mid-1950s, it was the large curving tusks in their weathered and earth-stained jawbones that were our treasure. We passed by the shards of broken pottery, cooking utensils and chopsticks.

Later we came to realize that there was a beauty too in the old food and drink containers. Although many were broken, there were some intact Chinese pots: beautifully glazed “Tiger Whisky” or rice wine jugs, delicate blue-patterned rice bowls, squat soy sauce and ginger pots, and many tiny opium bottles. We soon discovered that the best-preserved and intact vessels were often found in the soil and maple leaves banked up against the upslope side of larger trees.

The community’s international flavour was evident to us in the hundreds of bottles with embossed writing. Some came from local sources, like Victoria’s Silver Spring Brewery, but many others were from around the world. Some were imported Chinese beer bottles, with names like “Wingleewai”; others came from unexpected places such as the “San Miguel Brewery, Manila, P.I.” and “Steinike & Weinlig Schutz Selters” in Germany.

Many of the square-holed Chinese coins found were too corroded to read, but some indicated a source in Annam, now part of Vietnam. The hundreds of ebony wood “dominoes” and round glass gambling pieces that we found on the site are typical of the Chinese communities that sprang up in many parts of British Columbia around the turn of the century. The wooden dominoes are playing pieces for the Chinese game called gwat pai in Cantonese, which is likely the forerunner of the European game of dominoes.

On one outing in the early 1960s, David Neilson (my frequent partner in exploring Tod Inlet) and I explored a new area upstream on the bench above Tod Creek and found the broken bases of several of the large Chinese containers still popular among gardeners today. Beyond on the flats, where the main part of the village was, we found more solid remnants. Bricks, foundation platforms, and sheets of corrugated tin roofing indicated the location of some buildings. Bottles and pottery, cooking pots and two-man saw blades were scattered throughout the trees and clearings between the creek and the road to the cement plant.

A pig’s jaw in the Chinese midden. David R. Gray photograph.

Pigs’ teeth: the start of the whole story. David R. Gray photograph.

Chinese pottery and mineral water/gin container from Tod Inlet. David R. Gray photograph.

Sealing wax container found by Pat van Adrichem at the Chinese village. David R. Gray photograph.

Chinese toothbrushes and ivory razor handle from Tod Inlet. David R. Gray photograph.

When we first explored the site in the late 1950s, the only building still standing in the area was the old laundry house at the far end of the pasture, above the mouth of Tod Creek and overlooking the inlet. We used to avoid this house, as it was evident that it was still lived in. As kids we were a little afraid of meeting the people who lived there in fear they would forbid our further explorations. Evidently they took the bus into Victoria for the weekends, which is when we would leave Victoria for Tod Inlet. Much later on I came to realize that the men who lived there were probably Chinese, and that they could help me understand the artifacts we were finding nearby. So I tried to contact them by writing a message and my phone number on a cedar shingle and placing it on the front door of the old house.

Corrugated tin roofing material at the Chinese village site. Alex D. Gray photograph.

The response to my wooden letter came from Alf Shiner, head gardener at the Butchart Gardens. He told me about Yat Tong and explained that he shared the former laundry house with Yem (“Bing”) Choy, a gardener who joined the Butcharts in 1941. Shiner suggested that I go to the Loy Sing Meat Market on Fisgard Street in Victoria’s Chinatown and ask for Tong there. I did, but I guess my request seemed suspicious—a young white guy asking after an elderly Chinese man—and although Tong was well known in Chinatown, I got no help in finding him. Without a personal introduction, there was a wall between his culture and mine.

My next attempts to contact Yat Tong in the late 1960s included phoning and then writing to all of the Tongs in the Victoria phone book. This too proved fruitless, though I did talk with some very kind people. So I never met Yat Tong. I did learn more about him, eventually, through gardener Pat van Adrichem. Yat Tong and Bing Choy lived in the house until sometime in the mid-1960s. In the later years, Tong and Choy lived in each end of the building. A third man had once lived with them; when he died, the room he’d lived in was never used by the other two. Tong told van Adrichem that they would not open the room because the man had died.

Roy Carver, who began working at Butchart Gardens in the fall of 1949, also remembers Tong and Choy well: “One of my duties in later years was to drive Tong and Choy to Chinatown in Victoria where they purchased their sacks of rice and other items, delivering them and their purchases to their house in Tod Inlet.” Only three houses remained in the Chinese village at that time. Roy also remembered Choy with a box of cigars, handing them out when his wife in China had a baby.108

Yat Tong and Mary Todd (née Butchart) at the Butchart Gardens. Courtesy of the Butchart Gardens.

The Loy Sing Meat Market in Victoria, 2019. David R. Gray photograph.

Unknown youths digging for artifacts in the Chinese village area, 1979. David R. Gray photograph.

The house, the last remnant of the workers’ village, stood until the late 1960s, when it too was burned in a training exercise by the local fire department.

The site of the Chinese village was thoroughly scoured by bottle and artifact collectors in the years after our discoveries, and looks pretty empty today. There are stories of antique dealers and “pickers” coming into the area and breaking any ceramic pots they could find, in order to maintain the price of these Chinese antiques. However, there is still more than enough evidence of the community remaining to provide a valuable window into the past for park visitors.

The cement plant buildings at Tod Inlet remained relatively intact into the 1950s and 1960s.

In 1949, 15-year-old Roy Carver rode his bicycle from Prospect Lake to work at the Butchart Gardens: “I helped in the early years to unload barges of coal at the wharf in Tod Inlet for the furnace that heated the greenhouses, later changing over to oil…. I wandered through the cement plant ruins a few times, picking up a large bolt cutter and a few other tools.” Roy used a tractor with a bucket to unload the coal, at the same place where the Chinese workers had unloaded coal by hand almost 50 years before. It took him a week to unload a barge load of coal. The bolt cutters that Roy had salvaged from the abandoned plant are now destined for a place in the Royal BC Museum collections.

When Pat van Adrichem was working at Logana Farms, a loganberry farm in Saanich, at the end of 1951, the farm brought a truckload of cement tiles from the tile plant at Tod Inlet. At that time the tile plant was “going full bore.”

He started work at Bamberton soon after, in March 1952, and worked there full-time for 19 months as they were supplying cement to Kitimat for the construction of the hydroelectric dam and other facilities for the new Alcan aluminum smelter. Laid off on a Friday at the end of 1952 or early in 1953, he met with Ballantyne, the head gardener at Butchart Gardens, and was hired to start work at the gardens on Monday. When Bamberton received a big order for cement for a road in Calgary, the company asked Pat to come back to Bamberton, but he elected to stay with the gardens.

Pat recalled that customers were still getting flower pots from Tod Inlet in 1952, and the tile plant was still operating in 1953, but the increasing use of clay and plastic tiles was changing things. The cement tiles were cheaper but didn’t last as long. They collapsed when used in septic tank disposal pipes because of the constant wetness and corrosion.

Bolt cutters from the abandoned plant, 2019. David R. Gray photograph.

When the tile plant finally closed in about 1953, Heaney’s, a moving company, dismantled it and took the equipment out by truck. Afterward, a company called Evans, Coleman & Evans bought all the works from the plant, including the machinery for making flower pots.

Ian Ross, then the owner and manager of the Butchart Gardens, was in the United States for the winter when he received a letter saying that the equipment for making tiles and flower pots had been taken out. He was upset, as he had neither been informed nor given his approval. He returned to Victoria and drove down in his old Ford to Evans, Coleman & Evans and brought the pot-making equipment back to the Butchart Gardens.

When the old flower-pot moulds arrived at the gardens, Yat Tong was the only one who knew how to use them. The mould was bell-shaped, made of heavy metal and set upside down. The mix of sand and cement had to be just right because there was no internal reinforcement. Tong taught the others how to use sticks to tamp the cement down into the mould before the outer mould was lifted off.

When an early batch failed to set, Tong understood the problem—the pots had to set underwater. The gardens staff went back to town for the metal trays and tanks from Evans, Coleman & Evans, and Tong showed how to use them. Making flower pots became a usual winter chore at the gardens in the 1950s. The several different sizes of flower-pot moulds are still at Butchart Gardens and were put on display during the garden’s centennial year in 2004.

For years after the closing of the tile plant, hundreds of the cement flower pots—possibly rejects—were stored under the old cement plant office building. Some are still in use in various gardens in Saanich, and the Royal BC Museum now has some in their collection.

Sometime between 1953 and 1960, a Vancouver scrap dealer spent most of a winter cutting up the metal still left at the old plant. The workers cut large pieces up into chunks and welded eyes onto each so that their rickety crane could lift them onto their two old trucks and take them to Victoria. On one occasion, one of the men had a large piece of metal drop onto his finger. He shook off his heavy gloves and was quickly taken to hospital. Pat van Adrichem, who had witnessed the accident, collected the man’s gloves and placed them on top of the machine. When the injured man returned several days later, Pat pointed out the gloves to him. The man recoiled in horror from the gloves—part of his finger was still in there! Pat asked why he hadn’t taken the glove with him so that the finger could be reattached, but it seems he hadn’t even thought of that possibility. He certainly didn’t want to use the gloves again. Pat simply shook out the offending fingertip and put the gloves to good use for many years.

One piece of machinery that remained in the plant area near the kilns was a small rock-crusher, with jaws about 75 centimetres long and 15 centimetres wide. Pat and Roy Carver used to get it going and toss in small rocks to demonstrate its effectiveness. Eventually it was all removed, as people would often come from Bamberton to get “stuff” they needed from the abandoned plant.

The BC Cement Company merged with the Victoria firm Evans, Coleman & Gilley Bros. in 1957 and continued to do business under a new holding company, Ocean Cement and Supplies.

In December 1957, an appraiser from the firm Ker & Stephenson inspected and investigated the BC Cement Company property at Tod Inlet and prepared an appraisal: “I am of the opinion that a developer would be prepared to pay $30,000.00 for this site after the buildings have been demolished and removed, and that he would pay this sum in the expectation of putting in a subdivision and selling lots for the price mentioned above, namely $63,000.00. If the buildings were not demolished, then I am of the opinion that the property would not be as attractive to a developer and that it is unlikely that it could be sold as is for more than $20,000.00.”109

BC Cement became a wholly-owned subsidiary of Ocean Cement in January 1964. When Genstar, a large diversified company based in Montreal, purchased Ocean Cement in 1971, the BC Cement Company became part of a subsidiary, Inland Cement Industries of Edmonton. The cement company land around Tod Inlet land became an asset of a different nature.

An account that describes the early 1900s, written by columnist Gus Sivertz in 1958, sets the scene that would endure for the whole life of the Tod Inlet cement plant and beyond: “And here was the little cement mill with everything in a shroud of light grey dust: the workers’ gardens bravely battling the relentless encroaching pall of infinitely fine particles that rained down on the earth endlessly.”110

The most obvious pollution from the plant was airborne: a fine dust spewing from the chimney stacks, the product of grinding and burning coal, limestone, clay and gypsum.

On the forest floor to the west of the cement plant site, near the sole remaining chimney, the accumulation of cement dust from the plant, mixing with rainwater, has left a thin coating of concrete over large areas of ground. As the moss has grown over the cement covering, it is not immediately obvious that the ground is in fact covered in concrete.

The active cement plant at Bamberton in 1966. Alex D. Gray photograph.

In 1959, the BC Cement Company donated land near the Bamberton cement plant to the Province of British Columbia for the creation of a new park. Bamberton Provincial Park includes a Douglas fir and arbutus forest, a salmon creek, coastal eelgrass beds and a 225-metre-long beach.

Between 1960 and 1980 production at Bamberton declined as costs increased and workers engaged in a prolonged strike. As with the Tod Inlet cement plant, ownership changed from the BC Cement Company to Genstar, who decided to sell the property in 1982.

After several failed development proposals and millions of dollars spent in environmental cleanup, the Malahat First Nation bought the Bamberton property in 2015, a purchase that tripled the size of their land holdings.

Old drainpipes on the shore leading from the plant to the wharf area, 1994. David R. Gray photograph.

Dr. Sam Youlden (“Doc Youlden”) on the Kangaroo in 1973. David R. Gray photograph.

Tsartlip Elder Manny Cooper told me of a time many years ago when he shot a big buck up on the side of the hill near the cement plant, where on the whole hillside the ground was grey with cement dust. The deer had been eating salal leaves. When he cut the deer’s throat, he heard a strange rasping sound. He checked his knife, but there was nothing wrong there; he cut again and saw that there was cement at the bottom of the deer’s windpipe.

The pollution of the waters of Tod Inlet began in 1905 with the installation of septic tanks at the first 10, then 14 houses in the village, as well as the cement plant buildings. The overflow from the septic tanks in the village was carried by a single pipe into Tod Inlet. We have little knowledge of what other sorts of water-borne pollution came from the cement plant itself.

In the early 1950s my family harvested clams at the mouth of Tod Creek. A special treat was digging clams with Doc Youlden, taking them back to the Kangaroo, steaming the clams and eating them from the shell with vinegar, with a mug of hot sweet tea. The water must have been polluted then, but who knew?

Ivan Morris’s father, William, used to paddle from Tsartlip to Tod Inlet by canoe to harvest clams, as he and his family had always done. Ivan shared with me the story of the last time they harvested clams at Tod Inlet in the late 1950s: “When Father was an old man, digging clams, he had a sack about half full of clams. A fisheries guy went down and told him he shouldn’t be digging clams. He grabbed the sack and spilled them all over the beach. This was unheard of. You can’t treat an Elder that way. It hurt the family quite a bit. They gave no warning.”

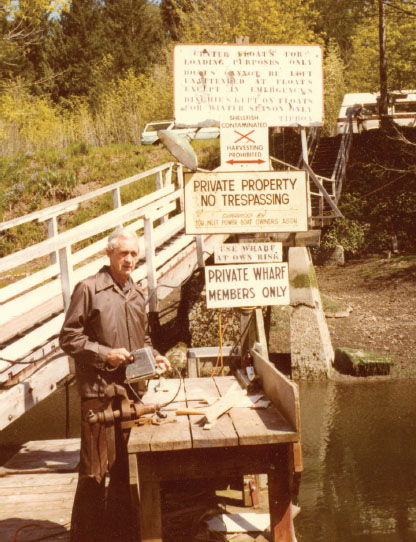

Eventually the Department of Fisheries posted a sign on the boat dock reading, “Shellfish Contaminated—Harvesting Prohibited.” The sign was still there in 1980.

Durrance Lake, which drains into Tod Creek, was a man-made lake, dammed up to provide a constant water source for the Tod Inlet cement plant. In the area known as Tod Creek Flats, the course of Tod Creek was rerouted in about 1915 to make a flat, dry area for Heal’s Range, the practice range for the Canadian Armed Forces. On many maps, Tod Creek’s upper reaches are labelled “Government Ditch.”

The most serious changes in the quality and structure of Tod Inlet water probably began with the Hartland Road dump, located about three kilometres due south of Tod Inlet. Starting as an unregulated dump site in the mid-1950s, for 30 years uncontrolled dumping created a dangerously toxic source of water-borne pollution.

The effluent discharge and runoff from the dump ran into Heal Creek, the outflow from tiny Heal Lake, and a tributary of Durrance Creek. Durrance Creek in turn flows into Tod Creek. An example of the kind of contamination the dump created comes from the removal of the contents of a paint works in Victoria to the dump, which resulted in a flow of lead and lethal metal components into the water system. The polluted material introduced into Tod Creek and Tod Inlet was a major blow to the life and vibrancy of the inlet. It began to kill much of the life in the inlet, including the eelgrass beds on the mud flats.

Tod Creek water became so polluted that the Butchart Gardens couldn’t pump it onto the lawns because of the smell, and the pollution of the stream due to leachate from the Hartland Road dump and agricultural waste resulted in the loss of the salmon run.

Alex Gray at the Tod Inlet Power Boat Owners’ Association wharf. Note the sign prohibiting the gathering of shellfish. David R. Gray photograph.

Populations also suffered because the Department of Fisheries allowed uncontrolled herring fishing. Jim Gilbert, the former fishing guide, thought that herring might have ceased to spawn in Tod Inlet because of changes in water oxygen content or temperature or the loss of vegetation, or maybe that larval forms of the herring couldn’t survive. Lingcod and chinook salmon populations disappeared; even dogfish didn’t frequent the area. By the late 1950s the creek and inlet were dying. By the 1960s, only the shells of mussels and the skeletons of barnacles remained. Deposits of grey-blue muck sludge covered the creek mouth and estuary of Tod Creek.

Among the last positive reports of salmon at Tod Inlet were published in Stewart Lang’s fishing column in the Victoria Daily Times: “Right in the mouth of Tod Inlet and near Willis Point and Indian Bay might be a weekend hot spot for those fishing Saanich Inlet. Salmon weighing up to 20 pounds are following an influx of big herring into the Inlet,” he wrote in 1968,111 and in 1970: “Main spring returns are coming from Indian and Coles Bays, to a lesser degree near the entrance to Tod Inlet.”112