From Sceptical Conspirator to

Minister of the Republic

(1923–1931)

Despite his many duties as head of the Republican Provisional Government, Niceto Alcalá-Zamora always found time during the early summer months of 1931 to write down his feelings during this most wonderful time of his political career. His belated conversion to republicanism had given him the prize that veterans of the struggle had long worked towards during the dark years of the monarchy. A relatively peaceful revolution had produced the coveted change of regime, and Alcalá-Zamora had climbed to the top of the greasy pole; things would get even better that December, when he was given the presidency of the young Republic.

In his diary, the former monarchist did not hesitate to express his gratitude to Lerroux for the ‘extraordinary sacrifices’ that he had made during those historic months. The Radical leader was a ‘giant’ politically speaking, whose stature only grew due to his ‘superior attitude and high self-esteem’. Alcalá-Zamora recognised that despite being Spain’s most eminent republican, Lerroux had accepted ‘a subordinate and at times secondary role in the preparations of the revolution, [and] in the drawing up of agreements and programmes’. Even if the veteran republican had ‘naturally been disappointed’ with this, he swallowed his pride to ensure victory: ‘Doubtless the general atmosphere was more wary of him [Lerroux] than even on other occasions, but he recognised and accepted that reality, showing once more his intelligence as well as his heartfelt commitment to the republican cause’.1

In many ways, these friendly words corroborate the bitterness that characterises Lerroux’s account of 1931 in his memoirs. Rather than being a crude hatchet job on his ex-ministerial colleagues, his later resentment reflects the fact that the leader of the only significant republican party in 1923 had been pushed aside by others in the Republican-Socialist Alliance of 1930. It is difficult to think that a man of Alcalá-Zamora’s personality and track record would have swallowed such a bitter pill. But Lerroux felt that he had no choice. He could not remain aloof from the only serious movement demanding a Republic, especially when Primo de Rivera had destroyed any prospect of the democratisation of the 1876 constitutional system. Ironically, it was the military dictator’s failure to institutionalise his seizure of power that made a Republic a serious possibility. Since deposed monarchist politicians were reluctant to confront the regime for fear that opposition could end up overwhelming the Crown itself, growing resistance to the new regime took the form of a republican tide that, much to the amazement of veteran republican leaders like Lerroux, swept the cities. In this context, the Radical leader could hardly stand aside although the price was high: co-operation with long-standing enemies and rivals like republican Marcelino Domingo, socialists Indalecio Prieto and Francisco Largo Caballero, and maurists and left-wing catalanists.

Lerroux Turns Against the Dictatorship

For Lerroux, the dictatorship had been created with the complicity of a desperate Alfonso XIII intent on eliminating any constitutional obstacle to his powers. Certainly the King did not challenge the military rebellion, but the idea that September 1923 ushered in a period of royal despotism was based more on republican prejudice than a sober analysis of political realities. When Primo de Rivera suspended the Constitution, he also seized control of royal prerogatives; the King never intervened less in matters of state than after 1923. This is not to say that the new dictator had a blueprint for power, as the coup was a desperate move to avoid a dangerous split within the armed forces. Apart from the collusion of Alfonso XIII, Primo de Rivera’s gamble succeeded because his fellow generals, including war minister Luis Aizpuru, were not prepared to defend the Constitution. The survival of the dictatorship therefore depended on Primo de Rivera’s ability to retain the loyalty of his military colleagues rather than the confidence of the Crown.

Lerroux was on surer ground when he placed the dictatorship in the broader context of the crisis of liberal constitutionalism after the First World War. That conflict had not ‘simply been a war’ but a ‘revolution’ and a ‘crisis of civilisation’ that had provided the perfect breeding ground for ‘the extremes’ of left and right. The fear of revolution, he argued, enhanced the prospects of counter-revolution, with liberalism seemingly incapable of preventing an ideological war to the death. For Lerroux, the republican movement was essential to avoid this dreadful outcome for Spain. It should reaffirm its commitment to ‘the ideals that gave birth to western civilisation’ and refuse to co-operate with the dictatorship while at the same time striving to ensure that the fall of Primo de Rivera would not produce the triumph of ‘revolutionary socialism’.2

This strategy was reinforced by the popular reaction to the end of constitutional government. Lerroux recognised that Primo de Rivera’s action was not unpopular among a public tired of conventional politicians, detecting a ‘millenarian spirit’ among his fellow Spaniards. This did not mean that the new regime would last. In an open letter to fellow republican Blasco-Ibáñez, he predicted that the pronunciamento would not signify the ‘salvation of the Monarchy’ but the opposite: the army, he insisted, had in reality provided ‘the coup de grâce’ against the Crown, ‘in the same way as it restored it [in 1874–75]’. Hence the dictatorship was the transient rule of a ‘soldier of fortune’ and would inevitably make way for the Republic. Yet Lerroux was adamant that this great event required the participation of the military to prevent its degeneration into revolution. For that reason, he ordered his party to abstain from active opposition against the new regime. Knowing Primo de Rivera well after meeting him in Paris during the First World War, he even agreed to a secret meeting with the dictator after the seizure of power to discuss the situation in Catalonia. When Lerroux later wrote about the dictatorship, he stressed its efficacy rather than its lack of legitimacy, asserting that it did not cause ‘any material damage to the country’ or ‘governed worse than its predecessors’. He went so far as to praise its restoration of public order, noting that for six years Primo de Rivera took advantage of its pacification of the Riffian rebels in Morocco to ‘suppress assassinations and put the wind up strike organisers’. Recognising the prosperity that produced a huge increase in public spending, he saw the dictatorship in classical terms as a temporary regime of exception and the dictator as a regenerationist ‘Costa like . . . iron surgeon’. Lerroux therefore had no particular animus towards Primo de Rivera as long as the dictator held to his promise not to remain in power indefinitely.3

This explains why Lerroux decided to retire temporarily from politics to start his own legal firm. However, his career as a lawyer was a short one. After taking on a few cases courtesy of his friend Dámaso Vélez, the greenhorn found that he preferred political to courtroom dramas. In June 1924, he travelled to Paris to meet the exiled leaders of the Conservative and Liberal Parties, José Sánchez-Guerra and Manuel García Prieto. They all rejected a revolutionary response to the end of the dictatorship, preferring a constituent assembly would decide the thorny issue of the monarchy. Soon afterwards, Lerroux joined the liberal opposition under Romanones. This was in contact with general Cavalcanti, the head of the King’s Household, and later with general Aguilera. The latter was involved in the first failed military coup against the dictatorship in June 1926 and Lerroux defended one of the conspirators, Domingo, in the subsequent military trial.4

Any chance that Lerroux would come to terms with Primo de Rivera came to an end in November 1926 when the general announced the creation of a new political system. The Radical leader indignantly refused to join the proposed National Assembly, seeing the dictator’s new party, the Patriotic Union (UP), as an attempt to cling onto power permanently. Moreover, he was well-aware of the rumours that the dictatorship would deepen its mutually advantageous relationship with the socialist movement by agreeing that the UP would share power with the PSOE.5 Yet Lerroux’s firm opposition to Primo de Rivera did not mean that his scepticism about the viability of any popular insurrection against the dictator had been allayed; on the contrary, he much preferred to align the republican movement with the more congenial politicians of the Restoration era.

The Republican Alliance

On 11 February 1926, Lerroux was proclaimed leader of a new Republican Alliance. This was born out of a proposal from Antonio Marsá, a member of both the Radical Party executive and the Escuela Nueva, a ‘New Generation’ republican intellectual group. During the initial negotiations in José Giral’s pharmacy, the Radical leader met other Escuela Nueva republicans such as Manuel Azaña and Luis Araquistáin for the first time. The Alliance brought together the Radicals, most of the Federal Party, Republican Action – an embryonic party led by Azaña and based on members of the Athenaeum – and provincial republican organisations including the Catalan Republican Party. Lerroux provided its headquarters and met its administrative costs. The purpose of the Republican Alliance was to re-energise the republican movement and make it the principal focus of opposition to the dictatorship. In this it was a success, as many critics of the regime came to republicanism after reaching the conclusion that Alfonso XIII’s fate was irrevocably bound up with that of Primo de Rivera. Thanks to the Republican Alliance, the Radical Party finally became a truly national organisation.

But clandestinity did not eliminate the worst vice of the republican movement: factionalism. Doctrinal and personal quarrels continued to sap energy. In 1929, Marcelino Domingo founded the Radical Socialist Party with Álvaro de Albornoz, a former Radical. They left the Republican Alliance following Lerroux’s insistence that it had to co-operate with monarchists in the restoration of legality and the convocation of a constituent assembly.6 They were also frustrated by Lerroux’s reluctance to organise an insurrection that would overthrow the monarchy. The success of the Republican Alliance only made the Radical leader more reluctant to gamble on an adventure that had little chance of success, and unlike Domingo or Albornoz, Lerroux had a long history of failed conspiracies behind him. Nevertheless, this revolutionary past was not much of interest to Radical Socialists, who accused Lerroux of wanting to restore the status quo ante.

While extremists within the Republican movement may not have liked Lerroux’s connections with monarchists, they could not question his commitment to the overthrow of the dictatorship. His contacts with dissident military officers and trade unionists led to a brief time in prison in November 1926 with Giral and a longer stay in 1928, in which the now veteran politician contracted furunculosis that was serious enough to require an emergency operation and two months convalesce at home. On bail and under police surveillance, Lerroux fled to Paris in 1929 and through Santiago Alba offered to become involved in José Sánchez-Guerra’s planned rising against Primo de Rivera, but as the former Conservative prime minister did not want republican involvement, he turned Lerroux down. The result, as the more experienced conspirator later wrote, was an ‘almost infantile adventure’ that January in Valencia, where ‘heroic and gentlemanly sacrifice’ did not even secure the support of the general designated leader of the revolt. This disappointment did not discourage Lerroux. Almost a year later, he instructed Diego Martínez Barrio, the Radical leader in Andalusia, to assist a more serious military plot that general Goded had been organising in the region’s military garrisons. It was only called off after the resignation of Primo de Rivera and the appointment of a conservative transitory government under general Berenguer.7

The End of the Monarchy

The departure of Primo de Rivera transformed Spanish politics. Although some former Conservatives and Liberals still harbored hopes that the monarchy could be saved, the republicans were intent on toppling Alfonso XIII. To achieve this historic goal Lerroux concentrated his efforts on securing republican unity, and this did not just signify bringing the Radical Socialists back into the camp but also reaching agreement with the new republican right led by monarchist deserters like Niceto Alcalá-Zamora and Miguel Maura, the son of the Conservative statesman. This was realised with the so-called San Sebastian Pact of August 1930, which included left-wing catalanists after obtaining a pledge of Catalan autonomy. Two months later, Primo de Rivera’s one-time socialist allies also signed up to a Republican-Socialist Alliance.

Despite his significant contribution to the San Sebastian Pact, Lerroux received few of its rewards. Not surprisingly, he clashed with the catalanists. While they wanted – and obtained – the right to define the Catalan Statute, Lerroux only supported it on condition that its implementation was reserved to the constituent assembly; the Radical leader remained stubborn in his belief that Catalan autonomy had to be placed within a wider territorial re-organisation of Spain that protected individual and local rights. Similarly, the creation of the Republican-Socialist Alliance did not signify that the socialists’ hostility towards their long-time political rival had mellowed. Therefore, when the Alliance created a Revolutionary Committee to prepare a new insurrection against the monarchy, Prieto and the catalanists vetoed Lerroux for the presidency. The Radicals’ allies could hardly deny them a place in the Revolutionary Committee – they were the most significant republican organisation within the movement – but they were determined to marginalise them as much as possible. This became all too obvious when the Revolutionary Committee transformed itself into the Provisional Government of the Republic. Without consultation, Lerroux was excluded from the premiership and key ministerial portfolios. After regarding Azaña, the designated war minister, as part of the Radical quota, Alcalá-Zamora proposed nominating Lerroux as foreign minister to keep him away from domestic affairs. The Radical leader responded by demanding the interior ministry, essential to his project of creating a ‘Republic of order’ that would prepare ‘serious and trustworthy’ elections, thereby ensuring the ‘definitive installation of Republican democracy’. Yet Lerroux was never going to get that job because Alcalá-Zamora and others feared that he would use the state’s electoral machinery to manufacture a Radical majority in the constituent assembly. In the end, Lerroux settled for the foreign ministry and a new communications ministry under his Radical colleague Martínez Barrio.8

This was a serious political defeat for the Radicals as it was a clear admission that its leader was going to occupy a secondary role in any future Republican government. Under these circumstances, he could have broken the Republican-Socialist Alliance. It is certainly true that he felt more comfortable with reformists like Melquíades Álvarez, Francisco Bergamín and Manuel Burgos y Mazo, and was certainly closer to dynastic Liberals like Romanones and Alba than he was to the socialists. Lerroux’s decision to stay reflected a political rule that US president Lyndon Johnson would later apply to FBI director J. Edgar Hoover: the Radical leader preferred to be inside the tent pissing out than outside the tent pissing in. He knew only too well that other party leaders were looking for any pretext to exclude the Radicals from the Alliance; if he had left over a squabble over ministerial chairs, it would have split the republicans and Lerroux would have been blamed by public opinion for dividing the opposition to Alfonso XIII. This could have torn the Radical Party apart as it had turned to the left after 1923 and its leader could therefore no longer rely on the unconditional loyalty of the membership.

In sum, Lerroux preferred to remain inside the Republican-Socialist Alliance to protect his party as much as possible during the uncertain times that lay ahead. Like in 1917, he refused to bet all his chips on the botched insurrection of December 1930, and the Radicals’ main contribution to the disaster was Lerroux’s signature on the revolutionary manifesto. However, Berenguer snatched defeat from the jaws of victory when he permitted the execution of two rebel captains, Fermín Galán and Ángel García Hernández. The creation of ‘martyrs’ undermined an already weak transitory government that had called elections in the hope of taking advantage of republican weakness. Lerroux was convinced that without the captains’ sacrifice, ‘the popular Spanish soul would not have raised its voice of protest and its desire for change in the municipal elections of [April] 1931’.9

Nevertheless, republican electoral success did not seem very likely in the last days of 1930. Lerroux was one of six Provisional Government ministers who eluded arrest, the Radical leader taking refuge in the house of Dámaso Vélez. He later hid in a flat in the western Argüelles district of Madrid where he created a false medical clinic in the name of a friend to meet contacts without suspicion. From there he re-established communication with imprisoned ministers who gave him the interim leadership of the movement. Desperate times did not alter the balance of political power within the Republican-Socialist Alliance; Alcalá-Zamora refused to give Lerroux access to its Military Committee. The Radical leader’s main task therefore was to restore links with provincial republican organisations and UGT leader Julián Besteiro, as well as providing aid to those who fled to France. At this point, the police had discovered Lerroux’s whereabouts, but he left undisturbed and met general Sanjurjo, the head of the Civil Guard from 1928, who was a friend of his from their days drinking and talking together in Madrid’s Fornos café. Lerroux tried to secure the general’s neutrality in the event of another rising, but the latter was non-committal. Even so, the very fact that a meeting took place was evidence enough of the government’s crumbling authority, and by March 1931 all of the Provisional Government’s ministers were back on the streets. A change of regime seemed imminent, but Lerroux was painfully aware that if the Republic ‘depended on the revolutionary organisation created by the Provisional Government, we would have been left high and dry’.10

The Republican-Socialist Alliance therefore reverted to electoral politics. Berenguer had been succeeded by Juan Bautista Aznar, and this admiral decided to replace a general election with a three-stage electoral process that would end with a national poll. The decision to begin with local elections was a curious one as these had traditionally given republicans and socialists their best results, but the date was set for Sunday, 12 April. The prospect of striking a blow against the monarchy in the towns and cities was far too enticing for petty partisanship, and as the best organised party within the Republican-Socialist Alliance, the Radicals provided the most candidates. Lerroux himself concentrated on rebuilding the party in Barcelona to prevent his old enemies of the Lliga from winning as a majority on the city council. Although he was also concerned about the threat posed by left-wing catalanists, their influence was perceived to be on the wane.

Lerroux followed the municipal election results that Sunday night in his bogus clinic, as there was still an order open for his arrest. His joy at the unexpected Republican-Socialist Alliance victory in most of Spain’s provincial capitals was marred by the calamitous Radical performance in Barcelona, which lost in its strongholds to the Catalan Republican Left (ERC). Its leader, Francesc Maciá, took advantage of his triumph on 14 April to occupy the provincial council building and unilaterally declare a Catalan Republic. Emiliano Iglesias, the Radical leader in Barcelona, responded by proclaiming the Spanish Republic in the civil government building and pressuring captain general Despujol to disperse the catalanists. This was a complete failure, as Despujol was replaced by general López Ochoa who placed the garrison under the orders of Maciá. Radical Party impotence in Catalonia was then confirmed by the Provisional Government’s de facto acceptance of the new situation in the region.11

Lerroux’s role in the proclamation of the Republic in Madrid was almost as inconsequential. He could not see how the Republic could come from local election results. Although the scale of republican and socialist victories in Spain’s towns was unprecedented, any seasoned political observer could see which way the electoral wind was blowing in urban areas even before 1923. Moreover, monarchist candidates had still won a majority of councils, and therefore it seemed that there was still all to play for in the upcoming provincial and national elections. But critically the Republican-Socialist Alliance’s conquest of the towns dissuaded many army officers from actively defending the monarchy. In other words, the Republic was not the inevitable consequence of election results but rather the result of a revolutionary rupture occasioned by the occupation of state institutions by antimonarchists cheered on by mass crowds. With the military looking on and the Civil Guard being placed at the disposition of the Revolutionary Committee by Sanjurjo under the watchful eye of Radicals Dámaso Vélez and Ubaldo Azpiazu, the monarchical regime imploded. The departure of Alonso XIII on 14 April ensured the bloodless arrival of the Republic.12

Minister of the Republic

Although he spent the previous day in the Madrid home of Alcalá-Zamora to keep up with the news, Lerroux was stunned when an emotional Vélez informed him of the King’s departure at three in the afternoon of 14 April. This was followed by a summons to join the other members of the Provisional Government. The journey was more easily said than done. The ride to Miguel Maura’s flat (where the ministers had gathered), and then to the interior ministry building in the city centre, was anything but straightforward. His car could not escape the crowds singing the French Marseillaise or the republican anthem Himno de Riego. They proudly held aloft the tricolour flag that thanks to the Radicals had previously been popularised as the symbol of the Republic; it would formally become the national flag a fortnight later. Finally, at five o’clock, Lerroux arrived at his final destination in the Puerta del Sol. After the solemn proclamation of the Republic, the one-time outsider took up his first ministerial post the following day. His first speech as foreign minister received a good reaction from civil servants relieved that they would be judged by their actions and not by their political ideas; anyone not prepared to serve the Republic loyally were able to leave without losing their service benefits.13

From the outset, Lerroux was prepared to accommodate conservatives and monarchists. This does not imply that his Republic would merely be traditional Spain without a King. The Radical leader was clear that the new regime had to satisfy the wishes of his republican and socialist allies; their expectations of democracy could not be dismissed. For Lerroux, the Republic meant above all civil supremacy and the absence of military interference in politics; the separation of Church and state and the absence of the latter in religious matters; and a federal structure based on individual, municipal and regional freedoms. He also recognised that the Republic would intervene in social affairs in order to protect the weak and powerless; this would be the first step towards a more harmonious society. A more active state would also introduce secular education, improve public health, carry out agrarian reform to create more smallholders, protect workers’ rights, and favour direct over indirect taxation. Ultimately, the objective was nothing less than the secularisation of society in which the Church would no longer play a role in education or shape legislation in such areas as marriage and divorce.

This was an ambitious, if hardly novel, programme: in its essentials it reiterated the 1920 manifesto of Republican Democracy. The Radical Party presented this future vision of Spain in its meetings and public events throughout 1930 and 1931 to underline Lerroux’s commitment to social justice. More equality, the Radical leader argued, would not only produce a fraternal society free of socio-political conflicts but would also be the bedrock of a new republican patriotism and a barrier against the disorders that could produce the return of an authoritarian regime.

Lerroux entered government in 1931 still imbued with republican ideals. Despite the claims of his critics, he was not a hack politician without a programme or model of society. Yet there were great differences between leftist republicans and the Radical leader, and these would become more evident during the first months of the Republic. As an experienced political figure active in Spanish public life from the late nineteenth century, his analysis of the ‘social question’ became ever less militant. Adhesion to liberal principles tempered his republicanism. While he believed that the state could be an instrument of social change, he dismissed the idea that government decrees were enough per se to fight injustice and facilitate progress. More important, he averred, were individual initiative and pragmatism. Lerroux believed that the implementation of the republican agenda should be gradual, measured and guided by a liberal spirit that prioritised conciliation over confrontation. It certainly should not be begun by a transitory and ideologically heterogeneous Provisional Government. Its only mission, according to Lerroux, was the consolidation of a ‘radically conservative’ Republic based on public order and private property. Reform should be left to the forthcoming constituent assembly.14

If the timing of change was one issue that separated Lerroux from other ministers in the spring of 1931, another more divisive subject concerned the extent to which previous constitutional practice should inform the institutional framework and the political culture of the new regime. Left republicans and socialists maintained that the Constitution should represent a radical departure from the past, and Lerroux did not deny that the constitutional monarchy had many weaknesses. But he also argued that the Restoration system defended liberties and brought stability and suggested that its mechanisms to ensure the peaceful transfer of power between parties be adopted by the Republic. Thus for the Radical leader, 1931 did not mark a year zero but the recuperation of civil liberties and parliamentary government after the dictatorship. This recovery of political rights should not just benefit republicans but all Spaniards; a patriotic and fraternal Republic, he believed, should not be the exclusive property of any group.

Of course, Lerroux did not demur from Azaña’s dictum that the Republic should be governed by republicans. At issue was the definition of ‘republicans’. Reflecting on the municipal election results, Lerroux thought it an act of madness to institute tests of political purity. The Republican-Socialist Alliance may have obtained a historic result in the towns, and performed creditably in the countryside, but it nevertheless still lost to weak monarchical opponents.15 Therefore, it did not seem irrational to suppose that these voters would form the basis of a strong future conservative movement. The wily politician certainly understood the electoral advantages for the Radicals if they could capture the monarchist electorate for themselves; in this sense the interests of the party and the Republic were aligned. Since the overwhelming majority of parties and voters outside the Republican-Socialist Alliance were to its right rather than its left, it was political common sense to make overtures in that direction; radical change could not happen until there was a broad consensus in favour of the Republic.

This was not the dominant view within the new government. Lerroux’s republicanism had more in common with former monarchists like Alcalá-Zamora or Maura than with Azaña. Unlike other ministers, Lerroux preferred to proselytise among former liberal monarchists than dispatch the routine business of state. This reflected a broader strategy. Once the Constitution was passed and the Provincial Government dissolved, the Radical leader wanted to convert his party into a centre-right alternative to the socialists and left republicans. The Republic would then have its own turno system, and political stability would be guaranteed. He also saw Spanish monarchism as a talent pool. Lerroux did not want to govern with junior civil servants, journalists or intellectuals. In his speech to the Madrid Casino Club in May 1931, he pleaded that the former political elite should not hesitate to work with his Republic as this would represent ‘national opinion in perfect balance’ and prevent any danger of ‘the extreme right’ or ‘left’.16 Lerroux’s aspirations were encapsulated in the pithy phrase “a Republic of all Spaniards”. It would bring understanding and reconciliation between long-standing republicans and their traditional adversaries. With the proclamation of the Republic, he declared, the revolution was over. After 14 April, Spain would enjoy the benefits of gradual change within an open and tolerant regime that defended property.

Such a message could not appeal to a socialist movement still wedded to the class struggle. More surprisingly perhaps, left republicans were equally hostile. Colleagues like Azaña rejected the idea that elements of the old political class could widen the social base of the Republic. Lerroux responded to their hostility in kind. He became increasingly dissatisfied with the performance of other ministers, seeing them as a hindrance to his vision of nationalising the Republic. Within in his own ministry he faced fewer obstacles. He placed emphasis on continuity of personnel, spurning the opportunity to place his political friends in embassies and consulates. His deputy was Francisco Agramonte, a professional diplomat who had served the monarchy before April 1931 in the post of director general of Morocco and the Colonies. Given Lerroux’s lack of expertise and languages, he relied on the advice of his civil servants when he went to represent the Republic at the League of Nations in Geneva for the first time in May. During disarmament negotiations and debates on agricultural exports he did not depart from the lines established by his monarchist predecessor; as the new foreign minister, Lerroux told his fellow representatives, that he came to continue a ‘political task’ that was neither ‘monarchist nor republican’ but ‘Spanish and patriotic’. These moderate words were greeted with applause from his audience.17

Lerroux’s speech to the League of Nations was opportune as it coincided with disorders that culminated in the infamous burning of convents on 10–12 May. In Switzerland Lerroux deplored the pitiful response of his ministerial colleagues, which would be a harbinger of things to come. He did not hesitate to denounce the sorry affair as a plot to create a leftist Republic based on an alleged public demand for radical measures against the Church. As Lerroux warned, the latter had as an institution not been hostile towards the Republic and so ‘it was impolitic and unjust and therefore foolish’ to provoke a Catholic backlash. Certainly, the recognition of the new regime by the Vatican owed much to the conversations held between the foreign minister and the papal nuncio, monsignor Tedeschini. Lerroux had promised that the separation of Church and State would not take place unilaterally and stressed that it would not presage a period of religious persecution. Similar assurances were made to Spanish bishops.18

These comments indicated how far Lerroux had travelled from his youthful anticlericalism. He supported the principle of freedom of worship that recognised the rights of Catholics without discriminating against those of other faiths. Suppressing religious orders and payments to clerics had long disappeared from the programme of the Radical Party. Even secular education and divorce were not immediate priorities if they jeopardised relations with the Church. Lerroux’s pragmatism reflected his agenda of consolidating the Republic. By safeguarding the legal status of the Church, worship and its rights of association, Lerroux believed that Catholics would accept the new regime. Unlike his leftist colleagues, he did not consider them inherently reactionary or antirepublican, pointing out that Catholics were politically heterogeneous, and even included those in Alcalá-Zamora’s Liberal Republican Right (DLR) who had worked to bring about the end of the monarchy. To alienate them would doom Radical efforts to incorporate the right into the Republic.19

Lerroux Inveighs Against the Left

Lerroux’s “a Republic of all Spaniards” also had an economic dimension. Any revolutionary change provoked concern among businessmen and investors, and fears of political anarchy were exacerbated by the after-effects of the Wall Street Crash of 1929 which reduced trade and placed international pressure on the peseta. The Provisional Government took power amid the fight of capital, the closure of enterprises and a subsequent rise of unemployment. In this context, the designation of a socialist as finance minister was not helpful, especially a man like Prieto who was ignorant of the markets and prone to verbal gaffes. Lerroux was relieved that his socialist colleague did not embark on any radical economic adventures, although he put this down to circumstances more than to political acumen. For the Radical leader, government policy should concentrate solely on restoring confidence, as a rise in public spending or socialisation measures would only increase production costs and depress demand.

Lerroux’s public opposition to the policies of Largo Caballero in the labour ministry was a logical reflection on his views on the economy. It is absurd to claim that this reflected a desire to represent employers against the socialist defence of workers’ rights.20 As we have seen, the Radical Party supported state intervention to address the ‘social question’, and this included better working conditions and wage increases for peasants and workers. This was all about bringing the classes together. Moreover, and unlike others in the government, Lerroux had some notion of what it was like to run a business. So, while he recognised the legitimate grievances of organised labour, he was a firm champion of private property and free enterprise and argued that socialist remedies for the economic crisis were not just ill-advised but dangerous.

Lerroux was particularly critical about Largo Caballero’s efforts to transplant the framework of industrial relations into the countryside. The agrarian economy, he reminded the labour minister, could not be run like a factory or a shop. Of course, he did not fail to realise the politics of these measures. Forced employment, the rural equivalent of the ban of factory lockouts, facilitated the intervention of socialist councils and trade unions in the production process. The obligation to hire labourers within the local district from strict alphabetical lists provided by the unions meant that farmers had no freedom to select their workforce. Even worse, mixed labour boards [jurados mixtos], presided over by socialist inspectors appointed by the labour ministry, ordered wage rises and shorter working hours without reference to the agricultural cycle, the real value of the harvest, or the differences in production of each municipality. The inevitable result of this rise in labour costs was unemployment, but socialist mayors transferred the costs to employers by forcing them to provide paid work.

Although Lerroux was committed to improving the lot of underemployed and poorly paid day labourers, he was clear that the Republic was not about ruining the rural economy, especially if this was the price for ensuring socialist domination of the countryside. He was similarly unimpressed by the UGT’s determination to increase its influence among urban workers by attempting to control the arbitration panels within industry and commerce. Lerroux suspected rightly that ultimately the UGT wanted to be sole mouthpiece of organised labour. As the socialists themselves made clear, this was a necessary part of the transformation of the ‘bourgeois’ state. Largo Caballero’s decrees, which entailed the influx of his comrades into central and local organs of power, were part of a programme that included collectivisation and secularisation. These would be the levers that would propel Spain towards socialism. In other words, while the PSOE held the reins of political power, a UGT dominated state would own and manage the means of production and exchange.21

This march towards a socialist Republic not only threatened employers and property owners, but also the rival anarchosyndicalist movement. The CNT, of course, was never going to be a friend of the Republic. Indeed, it saw the events of April 1931 as the ideal opportunity to kickstart its revolutionary struggle for libertarian communism. But the CNT also entered the 1930s with an enormous appetite for revenge against a socialist movement that had co-operated with Primo de Rivera against it. The swift integration of the UGT within the Republican state ensured the victory of insurrectionist wing of the anarchosyndicalist movement over moderates; henceforth the CNT sought to break socialist hegemony by a series of strikes that would discredit its new arbitration system as well as preparing the ground for an insurrection against the Republican government. Employers quickly found that inter-union warfare was bad news for them. Despite obeying official strictures regarding pay rises and working conditions, industrial conflict continued unabated. This was one of the reasons why Lerroux saw the socialists as a destabilising element in government. Even before the constituent assembly had debated the question of whether the Republic should be liberal or socialist, the PSOE was taking advantage of its presence in the cabinet to appropriate parcels of power within the state and reinforce the position of its trade union partner. For that reason, Lerroux maintained that the socialists should not remain in power after the Constitution had been promulgated, and even before then a republican should occupy the labour ministry.

Yet the Radical leader had his doubts about whether his left republican allies were on the same wavelength. On taking office, he soon received disturbing reports from friendly army officers about the actions of their war minister. Lerroux considered Azaña one of the most dynamic figures of the government: he welcomed the reforms that dealt with the bloated size of the officer corps, since this deprived the army of the resources to modernise its armaments and installations. However, for the foreign minister, this was secondary to the task of converting the military’s passivity of April 1931 into real support for the Republic. This was an exceptionally good opportunity, he believed, as most army officers had concluded after the experience of the dictatorship that they should never again get involved in politics. Lerroux regarded as essential not only a liberal Republic that preserved public order, but also a military policy that rewarded the tiny minority of republicans without discriminating against the majority of professional officers who had loyally served the monarchy. Only on this basis, he argued, could recalcitrant monarchists be safely deprived of their commands and the threat of insurrections disappear. So Lerroux deplored the pompous verbosity of Azaña’s speeches whose sole purpose was to burnish an image of an energetic and radical leftist republican leader. His offensive language meant that the government’s measures concerning officer retirements, postings and the restructuring of ranks were interpreted as politically inspired reprisals against the officer corps. Lerroux continued to develop his already extensive network of contacts within the military, and made contact with those disillusioned with Azaña, promising them directly or via the retired General Staff major and future Radical deputy Tomás Peire that a future Radical government would address their grievances.22

The Radicals’ moderation received its political reward in the June 1931 general election. Lerroux was much more successful that Alcalá-Zamora and Maura in attracting not just those republicans who wanted an end to the revolution, but also former liberal monarchists who saw him as a symbol of stability and common sense. While the DLR failed to prosper in a generally leftist atmosphere, Lerroux was the most voted candidate on the electoral slates of both the Republican Alliance and the Republican-Socialist Alliance. He was elected to no less than five parliamentary seats, and received over 100,000 votes in Madrid, an unprecedented figure in Spanish politics. The overall result made the Republican Alliance the largest parliamentary grouping with 120 seats, and 89 of these deputies were Radicals, making Lerroux’s party second only to the PSOE in the Cortes. A once marginal political force was now a serious contender for government.23

On the other hand, the result of the 1931 general election was hardly a triumph for those who wanted a liberal and moderate Republic. This was a self-inflicted defeat, as its advocates supinely gave the socialists control of the electoral register, allowed the sacking of 3,000 councils elected on 12 April, and agreeing to an electoral system that exaggerated the victory of the winning electoral slate. Since in the main monarchists did not engage with the election, and Lerroux chose to remain within the government, the victory of the governing Republican-Socialist Alliance was assured beforehand. The most important feature of the election therefore was the distribution of places on the governing coalition’s electoral slates. In this, the interior minister Miguel Maura inexplicably refused to immerse himself in the negotiations, giving free rein to civil governors and the provincial leaders of the various parties. This led, as Alcalá-Zamora memorably put it, to a ‘struggle towards the radical extremes’ that ‘pronounced the excommunication of moderate republicans’.24 For every place given to a Radical or a moderate, 2.6 places were allocated to the socialists and left republicans.

Why was this the case? The role of the PSOE was critical. In socialist strongholds, local leaderships preferred to make pacts with left republicans to reduce the representation of those further to the right. This meant that the republican left were the biggest winners of the nomination process, as they were more likely to be included in socialist dominated slates while maintaining their quota within the Radical dominated Republican Alliance.25 The PSOE’s electoral strategy was logical. They wanted to take advantage of muscle provided by the UGT to establish a significant presence in parliament and aid those republicans who would not oppose their constitutional proposals. The marginalisation of Alcalá-Zamora’s Liberal Republican Right, although it did not have a direct impact on the number of seats obtained by the Radicals, shifted the balance of power within the governing coalition to the left. Azaña and not Lerroux was now its political centre of gravity. Realising this, Azaña, who had been elected in Valencia and the Balearics due to Radical support, decided to create his own parliamentary group with the socialists as his preferred allies. The real winners of the election were therefore the Radicals’ rivals on the left, as Lerroux could not obtain a majority that would enable him to govern.

The Radicals were not wholly comfortable with their unexpected new position on the right of the constituent assembly. Many of the party’s deputies still held to traditional republican values and biases, especially after the experience of the dictatorship. On issues like the Church, the majority agreed with the socialists and left republicans, and did not much like the conciliatory discourse of their boss. After all, anticlericalism was one of the original pillars of the party and ditching it would create a great deal of fuss, especially among those Radicals who joined in the late 1920s. Yet ultimately the party was nothing without its charismatic leader. As we shall see, during the Republic Lerroux would encounter internal resistance, and even lose some of his colleagues, but as long as his leadership was the party’s most important asset, he was still able to impose his agenda.

The evolution of the Radicals into a centre-right movement was also aided by other factors. These included its changing base as monarchist liberals flocked to the party. Also significant was the changing political context. Socialist demands for greater state control of the economy provoked the unanimous opposition of Radicals, and many were more strident in their criticisms than their leader. Proposals for greater regional autonomy did not muster much enthusiasm either and Lerroux had to use all of his authority to convince his deputies to support what had been agreed in the San Sebastian Pact. Without the religious issue, the Radical Party was indistinguishable from the Liberal Republican Right.

So it was hardly surprising that divisions between Lerroux and his left-wing partners in government deepened after the election. His ‘Republic for all Spaniards’ faced its most serious challenge in the constitutional debates. The socialists and left republicans advocated a regime that placed secularism and collectivism above civil liberties and representative government. The socialists supported left republican leaders such as Azaña, Domingo and Albornoz when they denounced Lerroux as the last defender of outdated monarchist politics. The Radical leader’s own inconsistencies only facilitated the work of his rivals. Lerroux had little confidence in the proposed Constitution but did not want to burn his bridges with a republican left that he would need to govern in future. He really wanted the whole issue to be delayed until the revolutionary passions of April 1931 had subsided. Lerroux warned against Spain becoming ‘an experimental guinea pig’. But this was precisely what the opponents of a moderate Republic wanted.

The new foreign minister cut an increasingly isolated figure in the Provisional Government. Much of this was self-inflected. He distanced himself from many of its most controversial measures in order to elude responsibility and protest against his ‘bottling up’ within his ministry. He took advantage of his post to spend long periods abroad, especially in September 1931 when he chaired an assembly of the League of Nations. As relations with the Vatican began to deteriorate, Lerroux gave a formulaic defence of government policy, while cordially hinting that a Radical administration would do things differently. His de facto abstention from daily politics left his party rudderless during the constitutional debates. Rather than provide a clear and consistent stance that would obtain conservative support, his deputies preferred to pick fights with the socialists on questions that they vainly hoped would bring the left republicans back to them. Lerroux himself, anxious to avoid giving any hostages to fortune, seemed to prefer the public meeting to parliament, and sought to enhance his public image with more right-wing voters by calling his party ‘conservative Republican’.26

This meant that Lerroux did not take part in the so-called ‘responsibilities’ debates when republicans demanded that the King and leading members of the dictatorship and the Berenguer government be put on trial. He left the famous Article 26 parliamentary debate on the religious issue early, although only after he gave his deputies a free vote on Azaña’s motion which undermined a more moderate decision taken earlier by the government and which provoked the resignation of Alcalá-Zamora. Since Article 26 dissolved the Jesuits, banned religious orders from teaching and economic activities as well as giving parliament the right to dissolve them and confiscate their assets, Lerroux quickly clarified that his party had only voted in favour of the separation of Church and State. The Radicals, he went on, were not committed to the rest of the Article, or indeed the other ‘ultra-radical criteria’ of the Constitution that denied ‘the rights of citizenship to those who did not share our ideas’. He would respect all constitutional clauses while ‘not in power’ but intimated that when he takes office he would promote ‘a policy of consensus, tolerance and respect for the other’.27

Lerroux’s lack of leadership at this critical juncture in the history of the Republic needs to be placed in the wider context. The convergence of socialists and left republicans gave the Radicals little opportunity to play a more active role as this would have entailed accepting the definition of Spain as a ‘Republic of workers of all classes’, as well as other leftist shibboleths like regional autonomy and expropriation without compensation, which subordinated property rights to the whims of parliament. The marginalisation of the Radicals also meant that they had little input in the institutional organisation of the new Republic, and their well-founded proposals on bicameralism and the inviolability of a directly elected presidency were consigned to the dustbin of Republican constitutional history. Certainly, one cannot accuse the Radicals of devising a constitutional distribution of powers that were ‘confused, anarchic and impractical’ and that in Lerroux’s opinion problematised ‘the exercise of presidential, governmental and parliamentary power’. Ironically, the only issue where the Radicals succeeded in isolating the socialists concerned female suffrage, and on that occasion the party disowned its own deputy Clara Campoamor by opposing votes for women.

The Radicals only supported the Constitution in order to remain within the political system. Lerroux was convinced that it needed to be revised before the ink was dry. During discussions with Cambó in Paris that autumn, the Lliga leader advised him that the Radicals should concentrate their efforts on reducing the obstacles to constitutional reform because ‘the Constitution that they are voting on is a centipede that cannot be sustained’. In an interview with Ahora weeks before its promulgation, Lerroux warned that it would be difficult to enforce the Constitution because one had to combine loyalty to its clauses with ‘indispensable flexibility’ towards its ‘pernicious precociousness’. The text reflected ‘the evolutionary stage’ of a people that Spain ‘does not yet have’.28

Azaña Takes Power

The resignations of Alcalá-Zamora and Maura over Article 26 created a difficult political problem. As there was still no Constitution, the socialist president of the Cortes, Julián Besteiro, provisionally took on the powers of a head of state while a solution emerged from within the Provisional Government. To the surprise of many of his ministerial colleagues, Lerroux provided the answer. Knowing that he was in a minority within the cabinet, Lerroux ruled himself out of the premiership, and proposed Azaña instead. He knew that the left republican leader enjoyed the confidence of the socialists, and given that he provoked the crisis, it seemed obvious that Azaña should be the man to end it.29

Lerroux’s refusal to fight for the top job was logical. The departure of the Liberal Republican Right from the government and Alcalá-Zamora’s evident desire to lead a movement that would revise the Constitution suggested that the Republican-Socialist Alliance of 1930 was broken. Azaña’s new government, Lerroux reasoned, would be ephemeral, created only to pass the Constitution and elect the first president. After that, his nominal subordinate within the republican movement would have to resign, as Azaña was not politically strong enough to lead a government needed to pass the subsidiary constitutional legislation or continue the reforms interrupted by the June 1931 election. In the Radical leader’s mind, there were three options: the status quo, a PSOE or a Radical led government. Lerroux preferred the first, as long as the socialists occupied fewer ministerial posts, with Largo Caballero being one of the casualties. If the socialists refused and left the government, the Radicals were prepared to lead an exclusively republican government that would dispatch a minimum legislative programme before calling fresh elections in the following spring or summer.30 Lerroux was only too aware that he could not govern with the current parliament as the socialists, radical-socialists, the ERC, and conservatives could come together to vote down his government. The Radical leader was also conscious of the risk that the socialists and left republicans could form a coalition, although he believed that circumstances worked against the formation of such a government. After the bitter constitutional debates, it seemed to him inevitable that the legislative programme needed to be moderate; the downturn in the economy, worsening industrial relations and the deterioration of public order were evidence enough that the socialist presence in government did not contribute to the stabilisation of the Republic.

The Radicals’ problem was to convince the left republicans to form a coalition without the socialists. Lerroux did not understand the weak parliamentary position of his party. Irrespective of whether the Radicals joined a PSOE-republican government or not, it could not vigorously oppose its policies, as this would mean criticising the left republicans, their future coalition partners. This, of course, was the basic dilemma during the debates on the Constitution, and only a fresh election could overcome it. Meanwhile, Lerroux was obliged to strike a difficult balance between collaboration and opposition, and in terms of the Constitution this meant not moving beyond vague promises to ‘sweeten’, ‘slow down’ or ‘make more flexible’ its implementation. Unconcerned with the detail, Lerroux attempted simultaneously to reassure the left republicans that the Radicals would not support constitutional revision, while at the same time encouraging moderates to believe that they would be less sectarian than the left republicans. While in the short-term these contradictions excluded the Radical Party from power, Lerroux would benefit from the swing to the right in the 1933 elections.

Therefore, those who thought in the autumn of 1931 that Lerroux would soon be prime minister were being excessively optimistic. This prospect horrified the socialists, and they were prepared to offer the Radical leader the presidency in order to stave it off. Lerroux correctly saw this proposal as an attempt to decapitate the only serious opposition to the PSOE, and suggested Alcalá-Zamora. For the Radical leader, the former prime minister represented the constitutional past and present, and symbolised better than anyone else the end of the revolution. On a more mundane level, the elevation of Alcalá-Zamora also eliminated a rival for the moderate vote. In any case, Lerroux could not think of a better partner to steer the Republic away from the rocks of political extremism, asking rhetorically: ‘what other government could better obtain the confidence of the new president than a centrist coalition led by the Radicals?’31

Alcalá-Zamora’s candidacy also attracted the support of the left republicans mindful of political advantage. For them, his occupation of the presidency would neutralise a significant threat to the new Constitution. Therefore, with the support of all the parties of the Republican-Socialist Alliance, Alcalá-Zamora became the first president of the Republic on 11 December 1931. As expected, Azaña resigned the premiership immediately: he required the confidence of the new head of state to continue. Yet Alcalá-Zamora did not have complete freedom to appoint the prime minister. Following pre-1923 constitutional practise, any Republican government now required the confidence of both the president and a parliament that had met for at least five months in a year. Alcalá-Zamora’s responsibility, then, was similar to that of Alfonso XIII: he was expected to arbitrate between the government and the parliament, either choosing a prime minister who was able to secure a majority or giving a prime minister of his confidence the opportunity to obtain a majority by dissolving parliament and holding fresh elections. In the event that the president’s favoured head of government failed to win, the head of state had to accept the reality of a hostile new parliament. Unlike Alfonso XIII, however, the president could only dissolve parliament twice; after the second occasion, the Cortes would examine the reasons behind the dissolution and had the power to sack the president if it was deemed unnecessary. This potentially made the president politically responsible for a decision taken with the support of ministers.

This constitutional rule made a mockery of the principle that the head of state should be an honest broker between the parties. It was like giving football managers the opportunity to review a sending-off and dismiss the referee. What made this even worse in December 1931 was the uncertainty surrounding the status of the constituent assembly. Could Alcalá-Zamora dissolve a parliament whose length of term was undefined? The consensus within parliament was that it could only be dissolved once it had completed its work or that it could no longer produce majority governments. Therefore, Alcalá-Zamora had no choice but to work with the existing Cortes. In theory, the new prime minister would have come from the largest parties, which meant the PSOE or the Radicals. But neither wanted to head a government, and both argued for the continuation of the coalition. This would have a legislative agenda, although its extent remained conjectural; as we have seen, the Radicals preferred a minimum programme followed by an election, while the socialists and left republicans spoke of dozens of laws and a prolonged parliament. Alcalá-Zamora’s decision to approach Azaña for the premiership was thus a predictable one. This was not the case of asking the leader of barely 26 deputies to form a government, but a representative of the Republican Alliance who enjoyed the support of the socialists.

Lerroux did not object in principle to Azaña’s appointment. Yet as he reminded the latter, the Republican Alliance’s National Council had agreed that any coalition government should have a reduced socialist presence and a new incumbent in the labour ministry. If this was unacceptable to the PSOE, then an exclusively republican administration should be placed before the president. Azaña ignored these conditions. After consulting the socialists, the left republican leader informed the Radical leader that the PSOE would occupy education and public works portfolios, with Largo Caballero continuing in his post. This meant, as Lerroux realised, that the socialist permeation of all levels of the state would continue unchecked. Even worse, the Radicals were only offered the same ministries that they had held under Alcalá-Zamora: foreign affairs and communications. Azaña alleged that he could not get more: ‘the socialists were intransigent, irreducible and threatening’. Nevertheless, he bowed to the PSOE in order to avoid them going into opposition. Lerroux immediately refused to join the new government.32

Azaña should have turned down the premiership as the Radicals dominated the Republican Alliance. Indeed, he had previously promised the Radical leader that without his approval he would withdraw his candidacy. To be fair to Azaña, Lerroux wanted it both ways: he did not want to serve with the socialists or be seen as the politician responsible for breaking the Republican-Socialist Alliance. He therefore announced that while there would be no Radical ministers, his party would continue to vote for the government. On that basis, Alcalá-Zamora asked Azaña to form a more narrowly based coalition government. On 17 December, the new prime minister told the Cortes of his wide-ranging but ambiguous programme, and told deputies that there would be no elections until his ambitious agenda had been implemented. This was a disaster for Lerroux; not only were his hopes of an early dissolution dashed, but he was in political no-man’s land, both out of power and not in opposition.33

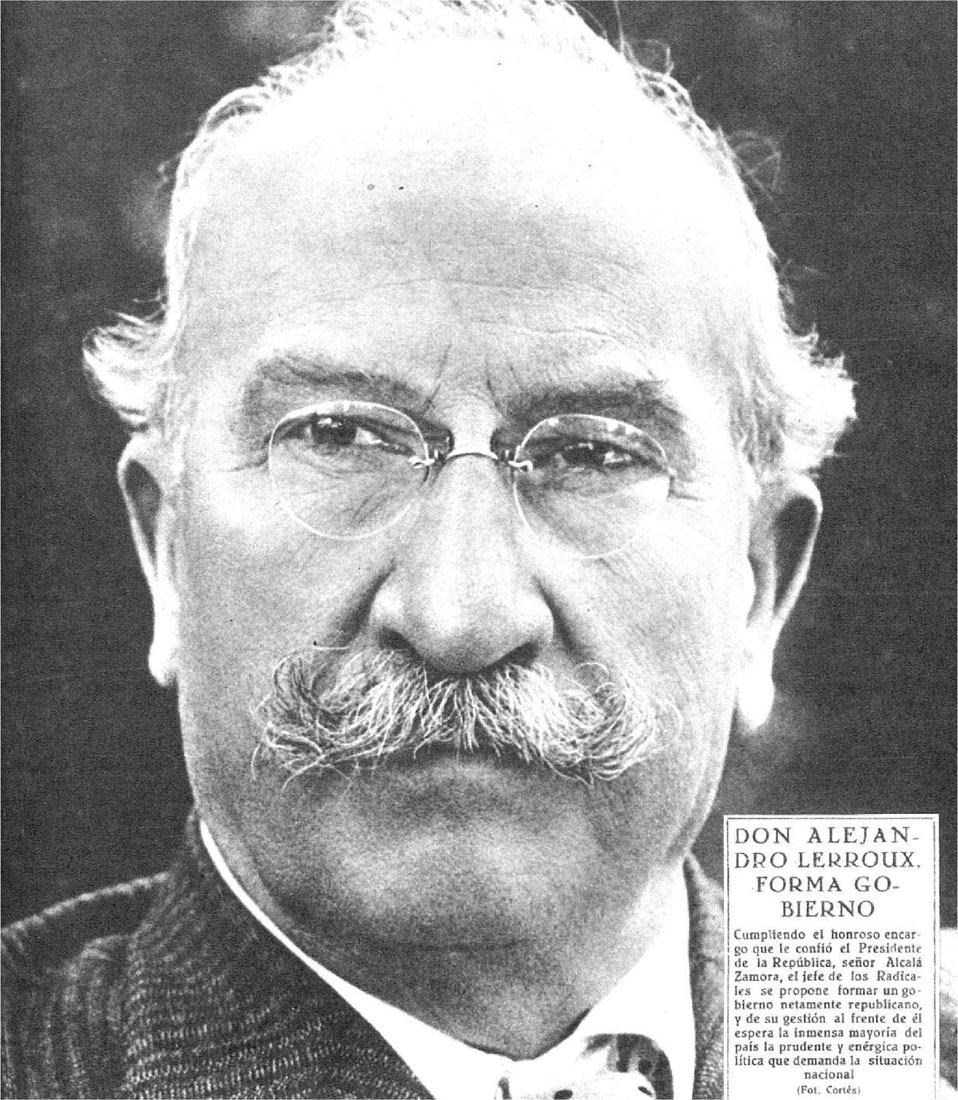

1 When the Second Republic was proclaimed in 1931, Lerroux was 67 and towards the end of a long political career.

2 Between 1931 and 1935, Lerroux made the Radical Party the most popular republican party in Spain. The Radical leader is here shown voting in the 1931 elections.

3 Lerroux founded the Radical Party in 1908 and was its only leader. The party leadership, from left to right: Rafael Guerra del Río, Juan José Rocha, Antonio de Lara and Ricardo Samper. Sitting from left to right: Diego Martínez Barrio, Alejandro Lerroux and Santiago Alba.

4 If Lerroux was an unremarkable journalist, he was nevertheless one of the greatest orators in Spain before 1936.

5 On his 69th birthday in March 1933, Lerroux received more than a million cards and letters from well-wishers all over Spain, anticipating his electoral triumph that autumn.

6 Lerroux formed his first government with left republicans in September 1933. It lasted for less than a month, and new elections were held two months later.

7 In October 1934, the President of the Generalidad, Luis Companys (on the left), rebelled against the Lerroux government.

8 In October 1934, Lerroux defended liberal democracy against the Workers’ Alliance of socialists and communists, enabling the democratic Republic to last almost two more years. In the photo and its enlargement, Lerroux comes out to greet a demonstration in support of the government.

9 General Domingo Batet (on the left) defeated the catalanist rebellion in Barcelona in October 1934. Lerroux receives Batet to congratulate him.

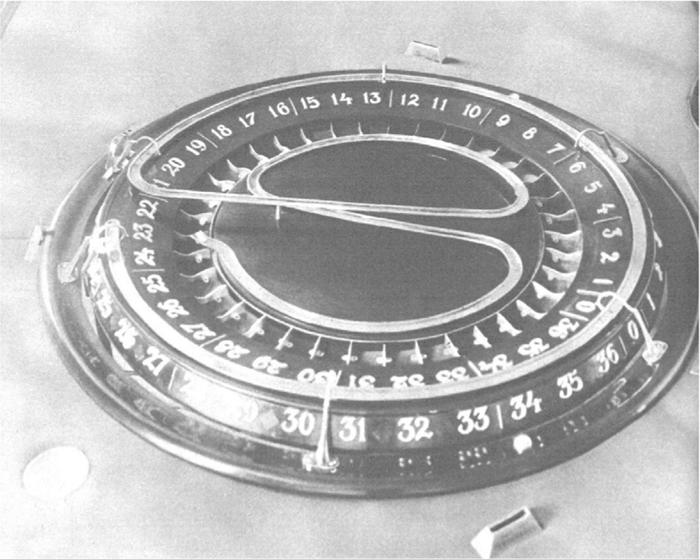

10 The estraperlo scandal was the promotion of a rigged roulette game that involved Lerroux’s nephew and other minor Radical officials. In the image, the roulette wheel set up in the San Sebastián casino.