… where, if we may use the expression, the manufactory of species has been active, we ought generally to find the manufactory still in action.…

—CHARLES DARWIN,

On the Origin of Species

Peter Grant began to wonder about the variation of animals and plants during his undergraduate days at Cambridge University, the university where Charles Darwin was a fair-to-middling divinity student. After graduating, Grant went on brooding about variation while studying goldfinches and cardinals on the Tres Marías Islands of Mexico, nuthatches in Turkey and Iran, chaffinches in the Canaries and the Azores, mice and voles around McGill University in Canada.

Rosemary came to the subject even younger. She grew up in a village in the Lake District, where she lived very much outside, and she remembers trailing after the old family gardener when she was four years old, asking him why individual plants, birds, and people are different one from the next. A row of vegetables, and no two were exactly alike. Birds: you could tell them apart. It was true of all the trees roundabout, beeches, birches, oaks, and ash; and all the common birds, tits, robins, blackbirds, finches.

“What applies to one animal will apply throughout time to all animals—that is, if they vary—for otherwise natural selection can do nothing,” Darwin says in the Origin. Slight variations, in Darwin’s view, are what the process of natural selection is daily and hourly scrutinizing. Variations are the cornerstones of natural selection, the beginning of the beginning of evolution. And as Darwin shows in the first two chapters of the Origin with wild-duck bones, cow and goat udders, cats with blue eyes, hairless dogs, pigeons with short beaks, and brachiopod shells, variations are everywhere.

Darwin studied the variation problem most deeply not in birds but in barnacles. In October 1846 he began trying to classify a single curious barnacle specimen that he had found on the southern coast of Chile. It was the very last of his Beagle specimens, an “illformed little monster,” the smallest barnacle in the world. To classify that barnacle he had to compare it with others. Soon the working surfaces of his study were littered with barnacles from all the shores of the planet.

The classic barnacle is an animal with the body plan of a volcano: a cone with a crater at the top. It colonizes rocks, docks, and ships’ hulls. Every day when the tide rolls in, each barnacle pokes out of its crater a long foot like a feather duster and gathers food. When the tide goes out, each barnacle pulls in the feather duster and clamps its crater closed with an operculum—a shelly lid. To mate, a barnacle sticks a long penis out of its crater and thrusts it down the crater of a neighbor. Since every barnacle in the colony is both male and female, this is not as chancy as it sounds.

What could be more of a sameness than a colony of barnacles? But Darwin, staring through a simple microscope, found himself descending into a world of finely turned and infinitely variable details. He wrote to Captain FitzRoy: “for the last half-month daily hard at work in dissecting a little animal about the size of a pin’s head … and I could spend another month, and daily see more beautiful structure.”

A few of Darwin’s barnacles. From Charles Darwin, A Monograph on the Sub-class Cirripedia, volume 2.

The Smithsonian Institution

In every barnacle genus he found astonishing variations. In one genus, “the opercular valves (usually very constant) differ wonderfully in the different species.” Elsewhere he found variations in the form of “curious ear-like appendages,” “horn-like projections,” and, in one strange species, “the most beautiful, curved, prehensile teeth.”

Everywhere he looked, individual differences graded into subspecies, subspecies shaded into varieties, varieties slid into species. Which specimens were the true species? Where should he draw the line? “After describing a set of forms as distinct species, tearing up my MS., and making them one species, tearing that up and making them separate, and then making them one again (which has happened to me), I have gnashed my teeth, cursed species, and asked what sin I had committed to be so punished.”

(Darwin’s friends knew just how he felt. The botanist Joseph Hooker wrote Darwin across the top of one letter, “I quite understand and sympathize with your Barnacles, they must be just like Ferns!”)

This profusion and confusion of barnacles helped confirm for Darwin that one species can shade one into another: that there is no species barrier. In many cases Darwin discovered one barnacle subspecies, variety, or race (he did not know which to call them) on rocks at the southern edge of a species’ range, and another subspecies, variety, or race at the northern edge of its range. In Natural Selection, his sprawling first draft of the Origin of Species, he notes that in many of these cases, “natural selection probably has come into play & according to my views is in the act of making two species.”

Of course Darwin assumed that the split, the act of creation, would be much too slow to observe any motion in his lifetime, because evolution proceeds at a barnacles pace. Darwin proceeded at a like pace through his barnacles. “I am at work at the second volume of the Cirripedia, of which creatures I am wonderfully tired,” he wrote in 1852, when he had been plowing through barnacles for six years, and still had one more year to go. “I hate a Barnacle as no man ever did before, not even a sailor in a slow-sailing ship.”

Variation is both universal and mysterious, one of the deepest problems in nature, and for Darwin it was for a long time completely bewildering. He wondered why, if his thinking was right, we see any species at all. Why not a continuous spectrum from tiny individual variations right on up the scale to kingdoms? Why for instance do we find a vampire finch and a vegetarian finch? (An example that Darwin might have liked, if he had known about the vampires.) Why not a whole smooth series of omnivores between the two, with a perfect series of intermediate beaks? Why not a blur, a chaos, an infinite web or Japanese fan of continuous variations?

In the sixth and final edition of the Origin of Species, in his chapter “Difficulties of the Theory,” Darwin puts this objection at the very top of the list: “First, why, if species have descended from other species by fine gradations, do we not everywhere see innumerable transitional forms? Why is not all nature in confusion, instead of the species being, as we see them, well defined?”

Very briefly, Darwin’s explanation is that the same process that makes varieties also destroys them. In the struggle for existence, some variants do better than others. When we look around us in the Galápagos or in Jersey or in New Jersey, the species of animals and plants we see are survivors. Varieties in between them have died off and disappeared, so that, after the long lapse of ages, we see only the victors and not the intermediate forms; we see the spines but not the webbing of the Japanese fan. “Thus,” Darwin says in the Origin, “extinction and natural selection go hand in hand.”

By this reasoning, if we were present at the creation of new species, if we could locate a point of origin, a place where the tree of life is growing new branches right now, we would see something less distinct and more chaotic. We would see a blur of variations shading from the individual up to the level of the species, or even up to the level of the genus. Wherever naturalists find such a blur they should suspect that here is a place where evolution is in fast action, where species are in the act of being born. Of course, Darwin thought even this fast action would be too slow to watch. We would know that we stood at the point of origin of new forms not by seeing turbulent motion, but only by seeing a sort of frozen foam from which we could infer the waterfall, “an inextricable chaos of varying and intermediate links.”

The thirteen Galápagos finches are just such an inextricable chaos of varying links. Darwin never knew how many links there really are, the chaotic and almost continuous variation in his Galápagos finches, because he brought back only thirty-one specimens, but he got an inkling of the problem when he watched the experts struggle with them. At first the ornithologist John Gould named one finch Geospiza incerta, meaning “ground finch, I guess.” Later Gould changed his mind and lumped that specimen with another. The fact that Gould ended up with the same total number of species of Galápagos finches as taxonomists currently do is a coincidence, because Gould’s thirteen were not the modern thirteen.

Taxonomists can be classified into splitters and lumpers. Faced with the diversity of Darwin’s finches, some splitters recognized dozens and dozens of species and subspecies. Some lumpers went so far as to call them all a single species. Generation after generation of naturalists made brief pilgrimages to the Galápagos, or puzzled over the specimens at the British Museum and the California Academy of Sciences. There were so many freaks, so many misfits that broke the serried ranks in the museum drawers. “The extraordinary variants,” one ornithologist declared in 1934, “give an impression of change and experiment going on.” Naturalists read and reread the reports of those who had seen Darwin’s finches alive, they sorted and resorted the stiff little rows of specimens in the museums, and they wondered what on earth was happening on Darwin’s islands.

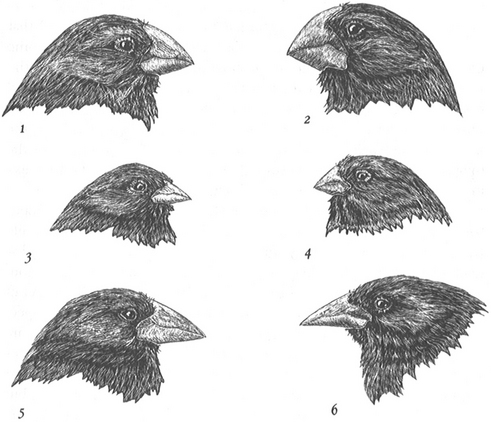

Darwin’s ground finches.

1) Medium ground finch, Geospiza fortis. 2) Large ground finch, Geospiza magnirostris. 3) Sharp-beaked ground finch, Geospiza difficilis. 4) Small ground finch, Geospiza fuliginosa. 5) Large cactus finch, Geospiza conirostris. 6) Cactus finch, Geospiza scandens.

Drawings by Thalia Grant

Today most taxonomists consider the thirteen species a single family (some say subfamily) of birds. Within this family or subfamily, taxonomists think four groups of species are particularly closely related, and so, for the moment at least, most taxonomists divide the family of Galápagos finches into four genera. In one genus, the birds all live in trees and eat fruits and bugs. In the second genus, the birds also live in trees, but they are strict vegetarians. In the third genus, the birds live in trees, but they look and act like warblers. In the fourth genus, the birds spend most of their time hopping on the ground.

This last group is the largest, with six species. It is also, for obvious reasons, the easiest to watch, and from the beginning the Grants and their team have focused on it. The Latin name of this genus is Geospiza: ground finches. The ground finches are a strange little club in themselves, a microcosm within a microcosm. The membership list includes the sharp-beaked ground finch, G. difficilis; the cactus finch, G. scandens; and also a large cactus finch, G. conirostris. Then comes a trio that has become as familiar to the Grants as Goldilocks’ Three Bears. There is a large ground finch, G. magnirostris; a medium ground finch, G. fortis; and a small ground finch, G. fuliginosa. The large ground finch has a large beak, the medium ground finch has a medium-sized beak, and the small ground finch has a small beak.

Within each of these three species, the beaks of individual birds are variable. That is, they blur together, just as we would expect if this is a place where the river is racing and the cosmic mills are turning fast. For instance, the species in the middle of the trio, the medium ground finch, fortis, sometimes shades into the species above it, magnirostris, or the species below it, fuliginosa. The very biggest specimens of fortis are just as big as the very smallest specimens of magnirostris, and so are their beaks. At the same time the very smallest specimens of fortis are just as small as the biggest fuliginosa, and so are their beaks.

Some of the world’s biggest fortis live on the island of Isabela; some of the world’s smallest magnirostris live on the neighboring island of Rábida. The largest of the fortis on Isabela are, even to Peter and Rosemary Grant, “almost indistinguishable” from the smallest of the magnirostris on Rábida.

You can’t distinguish these three species by their plumage, and usually not by their build or body size either. You have to tell them apart by their beaks. In the jargon of taxonomy, the sullen art of classification, the beak of the ground finch is diagnostic: it is the birds’ chief taxonomic character. But because the finches and their beaks are so variable, many of them “are so intermediate in appearance that they cannot safely be identified—a truly remarkable state of affairs,” as the ornithologist David Lack sums up in his famous monograph, Darwin’s Finches. “In no other birds are the differences between species so ill-defined.”

“CAUTION,” says a modern field guide to the birds of the Galápagos: “It is only a very wise man or a fool who thinks that he is able to identify all the finches which he sees.” At the Charles Darwin Research Station, on the island of Santa Cruz, the staff has a saying: “Only God and Peter Grant can recognize Darwin’s finches.”

PETER GRANT, having studied his chaffinches, nuthatches, mice, and voles, wondered what makes some species of animals and plants hypervariable and others not. He wondered why some of the most variable species will vary even in their variability, with one flock full of eccentrics and another flock full of conformists.

These were outstanding biological questions in the early 1970s, when Grant began looking for his next research project. (At the time, Peter was in charge of the research; Rosemary was in charge of logistics.) Theoretical and mathematical biologists were advancing paper dragons at one another in the pages of learned journals. Grant wanted to watch what actually goes on in nature. What he needed was a group of hypervariable species, well studied, variably variable, scattered across a set of remote and undisturbed locations. “The Galápagos were ideal,” he says. “Darwin’s finches were ideal.”

The Grants made their first trip to the Galápagos in 1973. That first year they worked with one of Peter’s postdoctoral students, Ian Abbott, and his wife, Lynette, among others. To the bemusement of Peter’s and Rosemary’s families in England, the Grants also brought their two daughters, Nicola and Thalia, then aged eight and six. The girls had already camped with them in Greece, Turkey, and Yugoslavia to watch nuthatches. (In those young field days, Rosemary’s biggest job was catching Nicola and Thalia.)

They found the birds as tame as in the days of Darwin, or of the shipwrecked bishop Berlanga, in 1535, who marveled at the birds “which did not fly from us but allowed themselves to be taken.” This is one of the strangest things about the Galápagos, after the strangeness of the animals themselves, and almost everyone who has ever written about the islands exclaims at it, including Cowley the buccaneer and Lord Byron (successor to the poet), who stopped there while returning a dead Polynesian king and queen to the Sandwich Islands.

Cowley wrote, in 1699, “Here are also abundance of Fowls, viz., Flemingoes and Turtle Doves; the latter whereof were so tame, that they would often alight upon our Hats and Arms, so as that we could take them alive, they not fearing Man, until such time as some of our Company did fire at them, whereby they were rendered more shy.”

Byron wrote, in 1826, “The place is like a new creation; the birds and beasts do not get out of our way; the pelicans and sea-lions look in our faces as if we had no right to intrude on their solitude; the small birds are so tame that they hop upon our feet; and all this amidst volcanoes which are burning round us on either hand.”

“The finches are much more afraid of hawks and owls than they are of us,” Peter Grant tells friends in Princeton. “When we walk up to them, the birds keep doing what they are doing; but when an owl comes near, they head for a cactus tree. A little while ago Rosemary was crossing a treeless spot. An owl flew over, and finches flew up from all around and landed on Rosemary!

“They are always perching on our shoulders, our arms, our heads. Sometimes when I am measuring one, a few others land up and down my wrists and arms to watch. I was looking out to sea with binoculars once, and a hawk landed on my hat. We have a picture of it.”

“Or you pick up a bamboo pole, set it over your shoulder, and begin to carry it,” says Rosemary. “Suddenly the pole is very hard to hold up. You are walking along wondering why it is so heavy. Then you turn around and see that you have a hawk hitching a ride on the back of it.”

“I used to have a wart on my back, although it is gone now,” says Peter. “A small black wart, up near the right shoulder. I went around in just shorts in those days, and on Genovesa, finches would peck at the wart.”

“What a difference!” says one veteran of the finch watch, Dolph Schluter. (Schluter coined some of the team’s favorite names for itself, including El Grupo Grant, the Finch Unit, and, for maximum grandeur, the International Finch Investigation Unit.) “In Kenya, finches flush as much as 30 meters away. In the Galápagos, the birds land on the rim of your coffee cup. If there’s only a little coffee left in there, they will land right inside it and take a sip. You can put your hand over it, and measure the bird. Mockingbirds on Genovesa would pick at our shoelaces. On the really isolated islands like Wolf, you could catch the birds by hand. Just reach out your hand and grab them.”

Galápagos hawks. From Charles Darwin, The Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle.

The Smithsonian Institution

Peter, camping in Shiraz, had once spotted a pair of nuthatches feeding near a rock. He put a few nuts on the rock, and hid himself, hoping to observe the birds’ beaks and feeding behavior at close range. Although he waited three hours, the birds did not come back. (“It would be better to use caged birds,” Peter noted tersely in his report.) But on Daphne the most famous beaks in the world were tapping him on the shoulder. He had Darwin’s finches perching on his knee, studying him.

Peter was keenly aware that despite the birds’ fame, despite their central place in the history of his field, no one had ever spent much time actually watching them. Darwin’s insights were strictly retrospective. David Lack’s were based mostly on inferences, museum specimens, and four months in the field. Bob Bowman had camped in the islands for less than a year.

“I think very quickly Peter saw the Galápagos as a gold mine,” says Schluter. “Not just a wonderful place to be, but a gold mine, a treasure chest. Today, looking down the road at what one could argue is the most successful field study of evolution ever carried out, you ask yourself, Just how early in the game could Peter have foreseen all this, twenty years ago? I think maybe he had a glimmer of it from the beginning.”

THAT FIRST YEAR the Grants and the Abbotts planned to stay in the islands for only a single season, so they worked fast, despite the heat. They studied twenty-one populations of Darwin’s finches on seven islands. At each site, at dawn, they unfurled two or three mist nets. Mist nets look rather like badminton nets on bamboo poles, but of so gossamer a weave that they are almost invisible to birds. The team left the mist nets up throughout the cool of the morning. They furled them again when the island got so hot that the birds trapped and struggling in the nets were in danger of overheating. Most days it was that hot by eight o’clock in the morning.

The members of the team went to work on each finch they caught in much the same style they do today, armed with dividers, calipers, and a spring balance. No one had ever subjected Darwin’s finches to so many different measurements and indignities, and no one had ever measured so many finches. Over the years, in fact, the Grant team’s measurements of live Darwin’s finches have far surpassed the number of specimens in the world’s museums. Off the island of Isabela, for example, there is a group of four small islands known as Los Hermanos, The Brothers. In Los Hermanos alone, Trevor Price eventually measured twice as many living, breathing specimens of fuliginosa as repose today in museums. (The Grant team has also measured virtually every one of the thousands of museum specimens.)

In a study of variation, everything hinges on the accuracy of the measurements. Some subjects—the dome of the shell of a turtle, the webbed feet of a duck, the diaphanous gills of a fish—are hard to measure accurately. You measure once and measure twice, and your first number is quite different from the second. If the measurements are only good give or take a few percent, and if variations from individual to individual are much smaller than that, your study is doomed from the start.

Fortunately the finches and their beaks turned out to be not only easy to catch but also easy to measure. A long series of finch watchers could go back and measure the same bird, and they would all get numbers within a fraction of a percent of each other. Weight turned out to be unreliable, because a bird’s weight goes up and down with the time of day and the time of year. But for other measurements the difference was almost always very small. For beak length, it was only a tenth of a percent.

“Hard facts” are those rare details in this confusing world that have been recorded so clearly and unambiguously that everyone can agree on them. The shape of a finch’s beak is a hard fact.

The Finch Unit’s measurements not only confirmed but heightened these birds’ reputation for variability. They began to reveal how extraordinary Darwin’s finches really are. The beak of the sparrow makes a useful comparison. Sparrows are closely related to Darwin’s finches: some taxonomists place all sparrows and finches in the same family. One of Peter Grant’s field assistants that first year was the Canadian biologist Jamie Smith. Ever since the early 1970s, Smith and his own team have been conducting a parallel watch, measuring song sparrow beaks on the tiny, remote island of Mandarte, British Columbia.

Smith has found that the beaks of song sparrows on Mandarte are all nearly the same length. It is rare to find a beak that is even 10 percent away from the mean. The probability of finding a sparrow that deviant is about four in ten thousand.

But in the Galápagos, the Finch Unit has discovered, the probability of finding a cactus finch with a beak 10 percent from the mean is much better than four in a thousand. It is four in a hundred. One of the Grants’ world records in this respect is the depth of the upper mandible of the medium ground finch on Daphne Major. Here, the probability of finding a 10 percent deviation is one in three.

That is one of the most variable characters ever measured in a bird. And Darwin’s finches are extraordinarily variable not only in the depth, length, and width of each mandible, and in the relative lengths of the upper and lower mandibles, but also in their wingspans, their body weights, and the lengths of their legs. Darwin’s finches are even variable in the length of the hallux, or big toe.

Again, Darwin did not realize that these finches are so extraordinarily variable, because he did not collect enough of them to find out. Nor would Darwin have expected this result. He thought a small population would offer fewer variations from which nature can select. Hence he assumed that natural selection would be especially slow on a tiny oceanic island like Daphne Major.

So even during their first season, the Grants and Abbotts could see that Darwin’s finches were more interesting than Darwin dreamed. And during that first field season, the island of Daphne Major sent the finch watchers an omen, a sign, a token of the difference a millimeter can make.

One day in April of that first year in the Galápagos, after a hard day measuring finch beaks, Ian Abbott climbed down to the welcome mat on Daphne Major to take in the view. The ledge is always encrusted with barnacles, each one a crude model of Daphne itself, a cone with a hole at the top. Because Abbott was sharing the ledge with these large, sharp barnacles, he wore a pair of old shoes. But because his wife and Peter Grant were the only other human beings on the island at that moment, Abbott wore nothing besides the shoes.

It was six o’clock in the evening, and the tide was coming in. Abbott squatted on his haunches, watching as the sun set on the neighboring island of Santa Cruz, and as hundreds of seabirds beat their way back to their roosts on Daphne Major. One millimeter beneath the future of Ian Abbott’s genetic lineage, a single barnacle towered above all the rest. And as the first waves lapped the welcome mat, this great white barnacle opened its lid, extruded its feather duster, bumped into something, and nipped shut as powerfully as only a behemoth among barnacles can.

At least, this is how they tell it now on Daphne Major, where the story is still passed down from one generation of finch watchers to the next. They say Abbott screamed. Abbott bellowed. Abbott danced up and down on the welcome mat. At that moment he hated a barnacle as no man ever had before.