Regionalization.

More than 30 million people live within the watershed region of the Great Lakes in North America, the largest body of freshwater on the planet. During the past two centuries, the region has been given a series of idiosyncratic designations such as the Great Cutover, the Manufacturing Belt, the Rust Belt, the Great Lakes Megalopolis, and the Megaregion by well-known urbanists from Patrick Geddes to Jean Gottmann. Emblematic of different processes of colonization, industrialization, and urbanization, these historical characterizations reveal a landscape of geo-economic and biophysical significance beyond the conventional limits of the city while testifying to a deeper ontology of regionalist canons whose focus is the hydrophysical system of the Great Lakes. Referencing a series of overlooked plans, projects, and processes, this essay demonstrates how the Great Lakes region is a macrocosm of change, a case study in the urban transformation of the continent with relevance to other parts of the industrialized world such as France, Germany, Britain, Italy, Russia, Japan, and Australia. As a revival of the revolutionary régionalisme of Jean Charles-Brun in late nineteenth-century France and as a challenge to the pervasiveness of globalization identified by Saskia Sassen at the end of the twentieth century, this essay proposes that the extra-national regionalization of spatial, ecological, economic, and political conditions is of crucial significance to the revision of the global discourse on urbanization.

The Region and The Globe

Satellite view of the Great Lakes (Superior, Michigan, Huron, Erie, and Ontario) and the Atlantic coast (Boston and New York City in far background) seen from the International Space Station. Source: NASA provided by the SeaWiFS Project, NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center, and ORBIMAGE

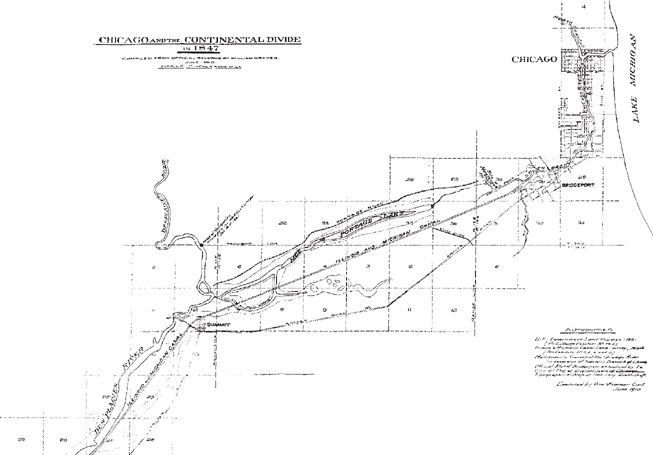

On January 2, 1900, a dam was unlocked on the southwest shore of Lake Michigan with only a few, anxious trustees to christen waterflow from the Chicago River, the first water course ever to be reversed in North America. Planned and built in ten years, the project was the golden child of two previous parent projects. The Chicago Portage in 1673 and the Illinois and Michigan Canal in 1845 had already set the precedent for geographic shortcuts across the continental divide.4 The third and final diversion was the Sanitary and Ship Canal, a 28-mile long, 24-foot deep, 160-foot wide trench completed seven years after Chicago marked the 400th anniversary of the New World during the World Fair. Responding to typhoid and cholera epidemics,5 the objective of the reversal was to divert sewage away from drinking water intakes located offshore in Lake Michigan for an exploding urban population. Technologically, the Chicago Canal was an engineering marvel in size and scale. Through chlorination of the water supply and a comprehensive sewer separation, typhoid fever was virtually eliminated by 1917.6 If railroads were the transcontinental infrastructure that secured Chicago’s future as the main portal to westbound–eastbound commerce, then it was the former Illinois and Michigan Canal which provided the navigable coastal infrastructure which linked two of America’s largest trading centers, New York and New Orleans, via Chicago. With the railways and canal locks, the mid-continental and intercoastal divides were well-conquered by the nineteenth century. Expanding upon this infrastructural legacy, the Chicago Sanitary & Ship Canal provided a vital infrastructural link that was essential to the growth of the city, as part of a process that required the development of water supply infrastructures well beyond the footprint of city boundaries at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Reversal of the Chicago River precipitated another effect. Channeled away from the lake, sewage poured into the Illinois River on its way to the Mississippi by way of St. Louis. Locally, complaints from downstream residents in southwest Chicago ignited almost immediately. As the sewage moved further downstream across state lines, so did the backlash. Regionally, St. Louis engaged in a bitter legal battle well before construction started in 1892. While sewage overloading played a role, the major case focused on the overexertion of shipping traffic from Chicago to the Mississippi, originating from a city outside the river basin. Geopolitically, the reversal of the river imposed external effects on residents in the valley of the Illinois River. Although injunctions submitted by the State of Missouri to halt the reversal were rejected by the Supreme Court, limits on water diversions were eventually enacted by 1925.7 In the decade-long process, the proceedings made visible the downstream effects of upstream urbanization. Geopolitically, it could be deduced that the effects of cities lie well beyond the governing limits of the city itself, and that the source of historical conflicts often flows from the discrepancies, or differentials, between biophysical systems and across human-created political boundaries.

Divide, Divert, and Conquer

1847 map of the planned Illinois and Michigan Canal running 96 miles (155 kilometers) that opened boat transportation from the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico. Source: Chicago Historical Society

Cordon Sanitaire

The 28-mile, 200-foot-wide 20-feet-deep Sanitary and Ship Canal that effectively reversed the Chicago River, diverting sewage away from Lake Michigan. Source: Chicago History Museum, ICHi-39314

Less than a quarter century after its construction, the Chicago diversion had other, major cascading effects: water levels across the Great Lakes dropped at visible rates. International conflict was imminent. Ten thousand cubic feet of water per second was being diverted every second from Lake Michigan, triggering alarming concerns from Ontario, the Canadian neighbor to the north who long opposed any freshwater diversions from the Great Lakes. Bordering on four of the five Great Lakes, the Province of Ontario was losing more than 300,000 cubic feet of water per minute from the diversion, a significant loss for the hydroelectric dam at Niagara Falls. Two more diversions and two more reversals would be constructed in less than a quarter century. Chicago was heading into a hundred-year-long battle over water rights. The State of Missouri joined forces with Wisconsin, Michigan, and New York in a coalition to put an end to the diversions.

The diversion focused a wide and contentious lens on the urban pressures, the physiographic magnitudes, the hydrologic complexities, and the jurisdictional constituencies of the region. The conflicts, confrontations, and crises that originated with the Sanitary and Ship Canal also laid the groundwork for a history of other water diversions, extractions, and abstractions up to the present day. Predated by water works across the Great Lakes such as the Erie Canal and Ohio Canal systems in the nineteenth century, followed by other mega-projects like the Niagara Falls hydroelectric dam and the St. Lawrence Seaway in the twentieth century, the reversal of the Chicago River can be interpreted as a turning point in cross-boundary water management, regionally and internationally.8 Technologically, the diversion displayed the prowess of civil engineering in one of the most important public works projects of the twentieth century.9 Leading to the formation of the Chicago School of Earthmoving, it set the precedent for other construction projects such as the Panama Canal.

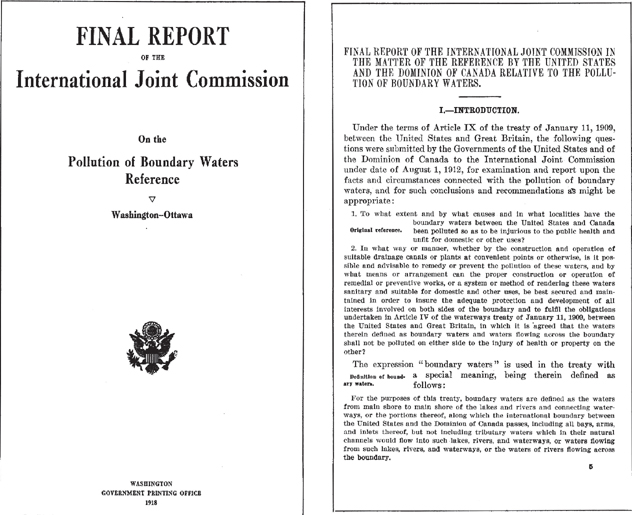

The reversal of the Chicago River also marks a major moment in the regionalization—an operative term that designates the geographic, economic, and ecological process of characterizing and forming regions according to overlapping geopolitical and biophysical boundaries—of the Great Lakes. Whereas in the past each lake was perceived as one of a series of loosely connected water bodies, a major change occurred in the understanding of their interconnectedness. The politics of the diversion later resulted in the milestone enactment of the Boundary Waters Treaty in 1909,10 soon followed by the inception of the International Joint Commission (IJC), a cross-border organization exclusively mandated to help resolve disputes and to prevent future ones, primarily those concerning water quantity and water quality along the boundary between Canada and the United States.11 More than a century later, the IJC has grown in size and influence to become a model of transnational cooperation and watershed governance, recognized worldwide. Paradoxically, the making of a simple water channel revealed the preeminence of the region and how it functions as an essential urban infrastructure that binds cities to their watersheds.

As the largest body of freshwater remaining on the planet, the Great Lakes region has simultaneously become home to more than 40 million people living within its watershed. Testifying to the robustness of water systems underlying urbanization, the current renaissance of turn-of-the-century regionalist tendencies is the contemporary manifestation of a richer, deeper ontology of regional characterizations over the past two hundred years whose fulcrum is the watershed of the Great Lakes. Sourcing the work of public intellectuals, scholars, and industrialists, the region has respectively garnered idiomatic designations such as the Great Cutover, the Rust Belt, the Great Lakes Megalopolis, and more recently, the Megaregion. Emblematic of different phases of colonization, immigration, industrialization, reclamation, and urbanization, the characterizations of this landscape have also championed, when considered retroactively, some of the most important regionalist canons in North America. This essay traces a cross-section of overlooked yet influential plans, projects, and practitioners during the past two centuries in an attempt to chart the emergence and transformation of the regional paradigm to reveal its contemporary significance to the global discourse on urbanization.

Transboundary Governance

The first major report by the Canada-U.S. International Joint Commission outlining major concerns, causes, and effects of urban pollution for the boundary waters shared between the United States and Canada, specifically focusing on water quality and water levels of the Great Lakes. Source: IJC, 1918

Landscape of Heat

Logging blocks for timber and fuel in northern Wisconsin in the region which later became known as the Great Cutover during the late nineteenth, and early twentieth century. Photo: Taylor Brothers. Source: Wisconsin Historical Society, WHS-1939

THE GREAT CUTOVER

AND THE CONTOURS OF CONSERVATION

Like the construction of the Calumet-Saganashkee and North Shore channels a few years later, the reversal of the Chicago River was undertaken in response to an unforeseen population explosion in the Great Lakes cities, a transit node between the urban markets on the Atlantic coast and the Grain Belt of the Prairies; lucrative logging and mining industries attracted European immigrants to Chicago as they sought to escape food shortages, oppressive taxes, and war. Revolutionary farm tools such as the McCormick mechanical reaper, the Baker wind engine, and the John Deere steel plough12 were invented throughout the Midwest in what became a golden age of agricultural innovation. But immigrants soon encountered a reoccurrence of their European plight of density and disease. With the rise of steam navigation, canal construction, rail transport, and crosscontinental mobility, the birth of the pre-Civil War commercial metropolis and the rise of the nineteenth-century industrial factory town led to an explosion of urban population followed by a concurrent rural vacuum. Chicago’s population, for example, jumped from 5,000 in 1840 to more than 1.5 million in 1900.13,14 In the absence of an integrated water supply infrastructure, sewage disposal in Lake Michigan polluted fresh water supplies. The diversion of sewage away from the Lake through the Sanitary & Ship Canal was the simplest and most logical solution. With a battery of concurrent farm drainage programs and land reclamation acts in outlying areas, super-urbanization15 became a trope for profitable, renegade trade generated from the industries of mass-logging and mass-mining. From mass-industrialization across the region there emerged a series of proto-conservation groups who would shape the future of urbanization.

Harvest and Heist

A massive reclamation project took place following the clear-cut logging and slash fires in the virgin forest regions of the midwestern United States and central Canada. From northern Michigan to southwestern Ontario, rampant clear-cutting of hardwoods (oaks, maples, and birches) and softwoods (like the white pines and spruces) stripped bare more than 65 percent of 40 million northern acres of choice timber in Michigan, Wisconsin, Ohio, New York, and Minnesota between 1890 and 1920. Historically recognized as the Great Lakes Cutover, the region served as the hinterland of modern commercial centers such as Boston, Philadelphia, New York, and Washington. Without any formal plans for reforestation, the devastation of forests resulted in the ongoing westward march in the late nineteenth century that left in its wake a landscape of stumps, swamps, and scoured fields. With land rendered useless from a logging perspective, a group of conservationists, planners, and industrialists emerged to develop strategies for the re-utilization of these razed areas.

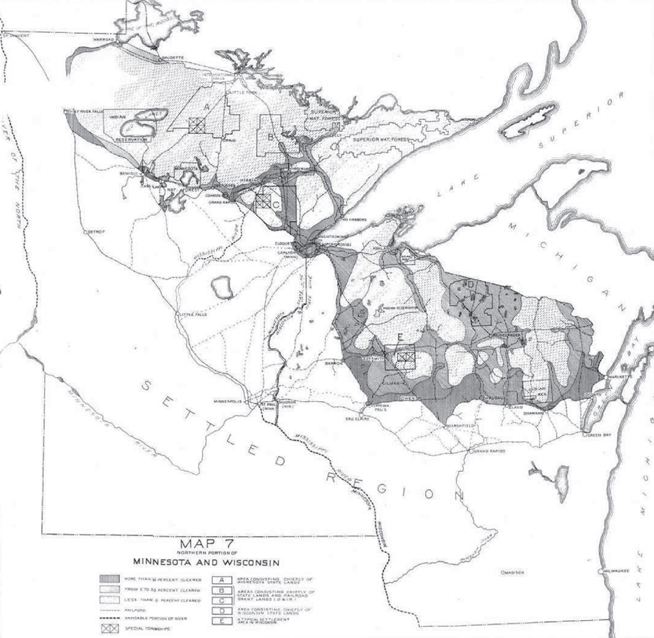

One of the most notable proponents of land reclamation and regional planning was Benton MacKaye.16 Recognized for his conception of the Appalachian Trail on the East coast, MacKaye drew up reclamation plans for the Department of Labor and the Forest Service in the early decades of the twentieth century. He was exploring new regional economic geographies in Minnesota and Wisconsin bordering Lake Superior. Influenced by Gifford Pinchot from the U.S. Forest Service and Michigan conservationist P.S. Lovejoy, MacKaye deplored the idle, non-productive waste of the more than 10 million acres of cutover lands in Michigan. As observed by Lovejoy in his critical survey of the Cutover Michigan’s Millions of Idle Acres, the crisis was essentially agricultural.17 Soils were either too wet or too infertile to turn a profit with crop farming. Clear cut logging also led to a rising water table and swampy agricultural conditions.18 Once a great timber producer, the Great Lakes state became a net importer. Homegrown hemlock was outcompeted by fir from the West, hickory from the East, and oak from the South:

“Michigan-grown hemlock, shipped 200 miles, sells at the same price in Detroit as does fir grown on the Pacific Coast, and shipped 2,000 miles. The hickory for the wheels of Michigan automobiles is coming from Arkansas and Mississippi. The oak for Grand Rapids furniture is being cut in Louisiana and Tennessee. Michigan does not even supply itself with enough telephone poles or railroad ties, but imports poles from Idaho and ties from Vir-ginia.”19

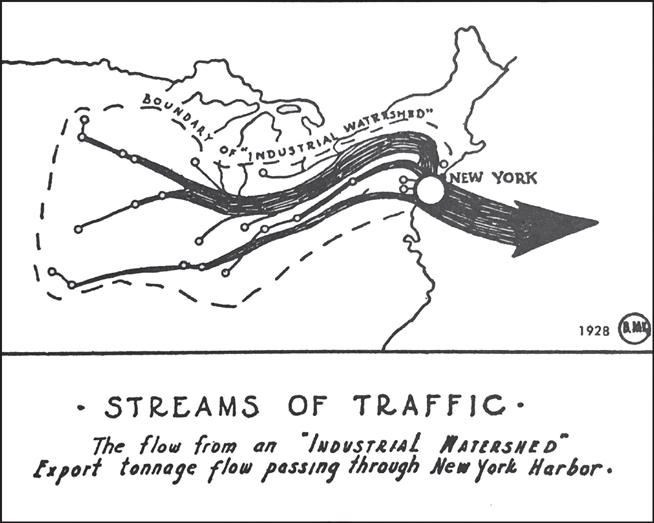

Regional Flows and Material Sheds

1928 map produced by Benton MacKaye showing material sheds from the Great Lakes region to the distribution hubs and centers of power on the East coast such as Boston, New York, and Washington, Source: ©1928 The New Exploration

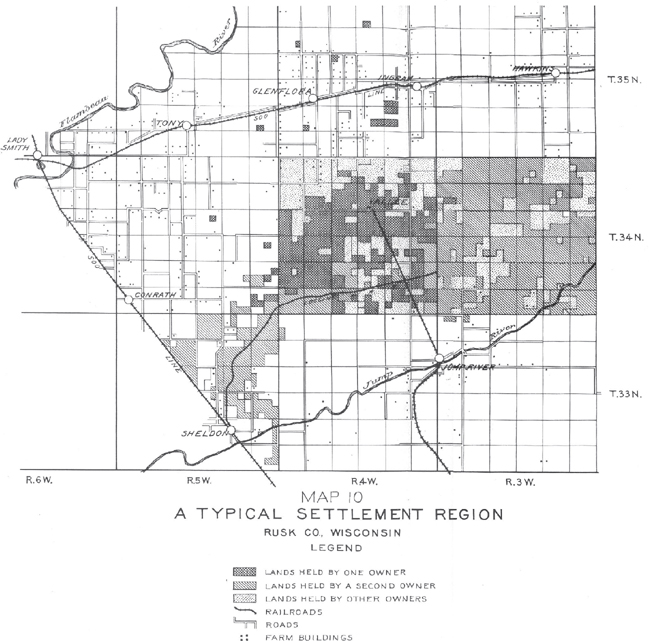

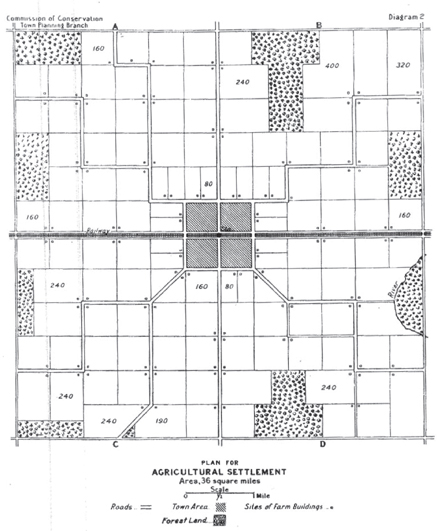

MacKaye’s strategies reconceived the landscape of the failed agricultural experiments of the northern Wisconsin region and several other cutover regions in the northwest United States. Borrowing from the prototypes of woodland settlements published by the Canadian Commission on Conservation, MacKaye and Lovejoy foresaw imminent urbanization by sketching out regional reclamation diagrams that coupled reforestation with repopulation across the landscape.20 As a countermeasure to careless, frontier land development in the nineteenth century, their work pioneered renewable economies of conservation areas, selective logging zones, and village settlements.

As early-century rebuilders, MacKaye and Lovejoy promoted long term, collective land management which would upset conventional paradigms of Promethean development which predominated the nineteenth century:

“These are the principles of the highest use of land; of the free soil basis of homesteading, efficient reclamation and State aid to self help; of community cooperation as against Robinson Crusoe independence; of forestry as against timber mining; of permanent employment for the lumberjack; and of the forest community as against the hobo logging camp.”21

Regional Pre-Planning

1911 resettlement diagrams of cutover lands drawn (above) and collected (following page) by Benton MacKaye for the U.S. Forest Service of the northern portion of Minnesota and Wisconsin. To different extents and scales, each one is marked by the presence of regional resources, forest configurations, infrastructure networks, and water bodies. Courtesy of Dartmouth College Library, MacKaye Family Papers

In this diagram it is assumed that the square form of land division for the separate farms must be adhered to as a condition precedent to the planning of the area. Varieties of size of holding from 80 acres (near the town) to 400 acres (remote from the town) are provided for, but all holdings could be made 160 acres if desired. A different plan is shown for each of the quarter sections, adaptable to the imaginary topography at the land, the only feature common to all the quarter sections being the main roads intersecting the township in two directions—one parallel with the railway and the other a right angles thereto. All the farms are grouped so as to give them convenient access to the town, where the same facilities are presumed to exist as, are described in respect of Diagram I. The total length of road usually provided in a fully developed township, not including boundary roads, is 60 miles. In this plan there are 36½ miles of principal and 3½ miles of secondary road, making a total of 40 miles. Every farm has sufficient road frontage, and the same length of boundary road is allowed for in both the above cases.

The object of these diagrams is not to suggest stereotyped or rigid forms of land division, but to show the desirability al abandoning such forms. Every township should be inspected and planned before settlement.

Reclamation and Reconstruction

With the groundwork laid by MacKaye and Love-joy, developments in land planning evolved into the research of Richard T. Ely, a German-trained reform economist from the University of Wisconsin. With his large-scale perspective on the challenges of land settlements, Ely proposed and later developed a new field of effective land utilization based on regional forest economics, arguing for a more-consolidated understanding of the cutover region. Disfavoring the uncoordinated efforts of the greedy land hustler or the uninformed reckless farmer, Ely theorized strategies that synthesized the imperatives of land conditions and urban economies. Those innovations later took shape in 1940 in a book titled Land Economics. Leading to the birth of a new field, this publication exhaustively articulated an alternative approach to the development of land.

Relying on the empirical understanding of biophysical resources, Ely’s work was premised on bringing long-term economic recovery to the failure of short-term agriculture across the emergent swamplands of the cutover region.22 Using a regional lens, Ely established the foundations for the reorganization of land, showing where a new geoeconomic structure could be achieved through collective models of governance that privileged the integration of hydro-logical systems, forest resources, regional cooperation, and state legislation. At its base, Land Economics uniquely hinged on the empirical understanding of hydrological resources:

“Percolating water found in the interstices between soil and rock particles constitutes a vast resource of water. It is estimated that if [groundwater in the United States] were brought to the surface it would form a lake from 500 to 1000 feet deep. […] The rights to underground water are even more complicated than the rights to surface water because the supply is invisible and the volume and direction of flow are usually unknown.”23

FIG. 3 REGIONS OF UNITED STATES AND CANADA

1. Agricultural Regions based upon O. E. Baker’s maps. See his “Agricultural Regions of North America,” Economic Geography, Oct., 1926, and U. S. Dept. of Agriculture Miscellaneous Publication 260, op. cit.

2. Geographic Divisions as used by the United States Census.

3. Economic Regions as used throughout the book, based in part on Maps 1 and 2 above.

Economic Geographies

Map of productive regions of the United States and Canada as a synthesis of agricultural and political divisions in North America. Source: ©1940 Land Economics Richard Ely

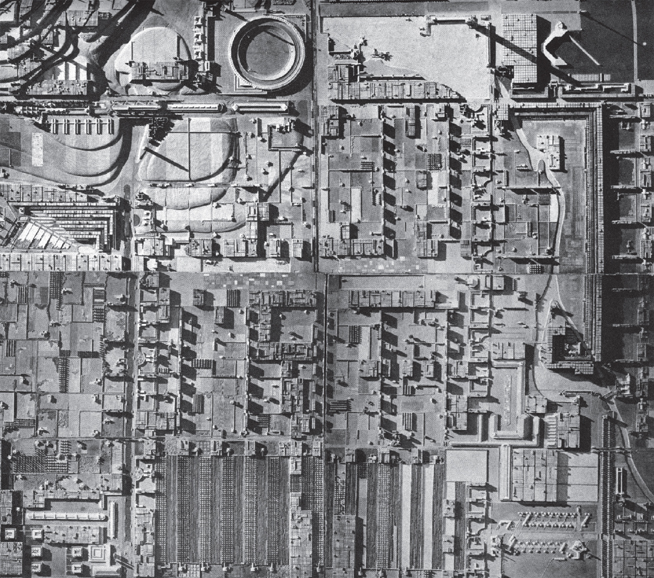

Agrarian Urbanization

Layout view of Frank Lloyd Wright’s 12’ x12’ model of Broadacre City, representing a decentralized Midwestern structure of urban land settlement in the 1940s. Source: Broadacre City Model photograph from the 1958 The Living City Copyright ©1958 The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale, Arizona

Landscape Economics

Founder of the American Economic Association and bullish proponent of labor organizations and the public management of resources, Ely premised on the understanding that groundwater resources and surface watersheds offered replenishable capital.24 In the cutover region, Ely promoted the de-privatization of the land—rather than the settling of it—taking it out of agricultural use for public forestry practices. Ely mapped out land uses as directly generated from soil types, micro-climates, and water resources that were primarily agrarian. In his view, collective farsighted reclamation of land had to supplant the nearsighted renegade efforts of private landowners or land hustlers. It was no coincidence then, that in the 1940s, Frank Lloyd Wright—a Prairie School architect from the Midwest—would unveil almost simultaneously an intricately detailed scale model representing a hypothetical 4-square-mile community proposal for the denuded landscape of rural Illinois. Aptly titled Broadacre City, the model experimented with a unique Midwestern structure where hydrology and topography prefigured as primary infrastructures amidst an expansive field of agriculture, housing, and civic services.25 Conceived at his Taliesin studio in Spring Green, Wisconsin, 150 miles west from Chicago, Wright’s urban–agrarian proposal was largely an antithesis of the European concept of the centralized industrial city.26 Almost two decades later, parallel to the land policy objectives of Richard T. Ely and the regional strategies of Benton MacKaye, Wright as an architect/urbanist distilled the essence of the land settlement challenge in the Midwest with his 1958 manifesto Living City, proclaiming, “We should have a system of economics that is structure […] that is organic tools.”27 Looking beyond the city, they all sought to escape conventional forms of conservation without reverting to pro-rural isolationism or anti-urban pastoralism. While their work remained reactive to existing conditions, they opened a broader prospect of the region as a design territory, capable of engaging more-diversified processes at larger scales, across longer periods of time. For them, in practice and in theory, the region was becoming the medium.

GLOBALIZATION AND THE CORROSION OF THE MANUFACTURING BELT

Before and during the two world wars, the Great Lakes states underwent a considerable rate of growth in the areas of weapons production, chemical processing, and automotive manufacturing. The abundance of iron ore, coal, and electricity along with vast fresh water resources and navigable waterways fed the development of large factory towns in the region of the Great Lakes and industrial metropolises of the northeastern seaboard. With an abundance of farm and factory labor, the region of the Great Lakes, especially near the Midwest, became a frontier of boomtowns.28 Large, centralized, heavy-industry facilities developed at a rapid pace to secure the region’s international reputation as the Manufacturing Belt.

Where timber and transportation had dominated the previous century, the discovery of taconite in Minnesota’s Mesabi Range fueled the industrial engine of the Manufacturing Belt.29 By World War I, Minnesota was meeting two-thirds of US demand for iron ore. Vast supplies of ore could be shipped by rail or by ship from Duluth at the western extremity of Lake Superior and moved eastward to steel mills in the lower Great Lakes located near vast supplies of Appalachian coal. Finally, long and flat steel for product manufacturing or construction projects made its way by rail to growing urban centers on the Atlantic coast.30 From this geographic network rose an industrial shed that was underpinned by the geophysical landscape of the Great Lakes. City appellations signified their might: Pittsburg the Steel City, Sudbury the Nickel City, Hamilton the Steel Town, Sarnia the Chemical Valley, Detroit the Motor City, Cleveland the Bridge City, Toledo the Glass City, Buffalo the City of Light, Milwaukee Supplier to the World.31

Rise and Fall of a Great American City

Dubbed the “Machine Shop of the World,” Milwaukee owed its rise to industries of machinery, meats, and malts which flourished after the Civil War but later declined after the Great Depression. 1901 Poster: Courtesy City of Milwaukee, Department of City Development

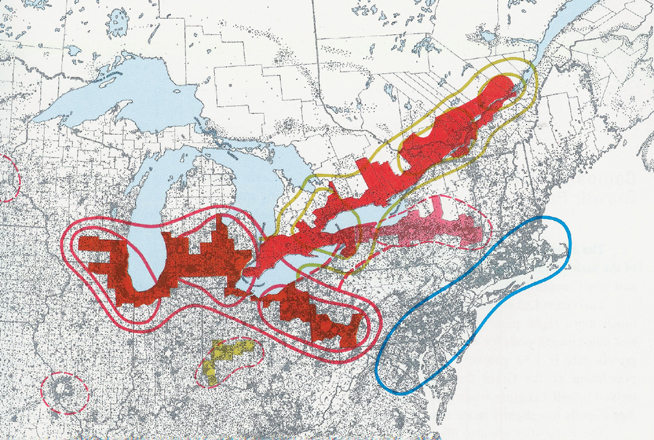

Sub- or Super-Nation?

Map of the manufacturing region of the Great Lakes with the consumer centers of the East Coast, depicted as one of nine “nations” across North America by geographer Joel Garreau. Source: 1981 The Nine Nations of North America © Joel Garreau

Deindustrialization and Decentralization A few decades after a relatively short-lived peak of production during and immediately following the world wars, the rate of transformation plummeted. The U.S. steel industry workforce fell from 509,000 workers in 1973 to 240,000 in 1983. Outsourced production, rising energy prices, and increasing trade deficits all contributed to manufacturing’s demise and the abandonment of heavy industry. From Wisconsin to upstate New York, the widespread pattern of deindustrialization had incendiary effects, including the decentralization of city centers. In his 1981 book, The Nine Nations of North America, East Coast journalist Joel Garreau aptly summed up the situation characterized as The Foundry:

“Tough is what defines North America’s nation of northeastern gritty cities in a multitude of ways. Gary. South Bend. Detroit. Flint. Toledo. Cleveland. Akron. Canton. Youngstown. Wheeling. Milwaukee. Sudbury. London. Hamilton. Buffalo. Syracuse. Schenectady. Pittsburgh. Bethlehem. Harrisburg. Wilkes Barre. Wilmington. Camden. Trenton. Newark. […] The litany of names brings clear associations even to the most insulated residents of other regions. These names mean one thing: heavy work with heavy machines. Hard work for those with jobs; hard times for those without. […] When columnists speak of managing decline, this is the region they mean. When they speak of the seminal battles of trade unionism, they place their markers here. When they write of the disappearing Democratic city political juggernauts, not for nothing do they call them machines, for this is where they hummed, then rusted.”32

What was once admired worldwide as the U.S. Manufacturing Belt became universally known as the Rust Belt.33 Burdened by large, overbuilt structures and public works disinvestment, this massive transition simultaneously paralleled the erosion of public infrastructures. America’s public facilities were wearing out faster than they were being replaced.34 From decaying sewers to bridge collapses, incidents across the region were indicative of aggressive deregulation programs that deferred maintenance and cancelled construction which exacerbated urban disaggregation and the hollowing-out of inner city cores.

The decline of the Rust Belt in the second half of the twentieth century mainly stemmed from four factors: the global mobility of corporations, the attrition of innovation; the inflexible demands of labor associations; the displacement of workers to new sectors of defense, oil, and aerospace in the Sun Belt; and an aging workforce. Policies for the globalization of the region and deregulation of national trade began with the General Agreement on Tariff and Trade in 1946, grew with the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994, and matured with the formation of the World Trade Organization in 1995. Transnational trading policies opened international borders southward and westward, where labor and raw materials were cheaper and environmental laws less stringent. This structural industrial change may have been inevitable according to regional industrialist Henry Ford:

“The belief that an industrial country has to concentrate its industries is not, in my opinion, well-founded. That is only a stage in industrial development. […] Industry will decentralize. There is no city that would be rebuilt as it is, were it de-stroyed—which fact is in itself a confession of our real estimate of our cities.”35

As a result of industrial deconcentration in the Northeast, boomtowns became ghost towns. While abroad, relocated industries found surrogate cities: Bangkok supplanted Detroit, Shanghai supplanted Cleveland, Taipei supplanted Toledo, and Mexico City supplanted Milwaukee.36

Disurbanism and Disassembly

The economic fallout further precipitated the population vacuums of inner cities and former boomtowns in the Rust Belt from the 1950s onward, largely leaving them victims of decaying oversized infrastructure, contaminated vacant land, heavy tax burdens, and social attrition. Copious amounts of money were poured into urban renewal projects—new stadiums or convention centers—in Detroit, Flint, Milwaukee, and Buffalo. However, despite good intentions, little has improved economic situations.37 Milwaukee for example now has twice as many murders as Los Angeles; Buffalo has twice the taxes of New York City; and Flint has the third highest crime rate in the nation.38 General Motors (GM) CEO Roger Smith closed down all the assembly plants in Flint, Michigan, leaving more than 40,000 people jobless and the entire city virtually bankrupt in the 1980s. Since then, mayors have toyed with tourism as a substitute for urban economic regeneration and environmental reconstruction, with very little, or no success. Despite its level of vacancy and abandonment, these landscapes of decline and neglect—disurbanization—have become progenitors of ecological regeneration, displaying the laten cy of biophysical dynamics that existed before industrialization.39

Aquatic Bio-Indicator

Brown bullhead from Wisconsin’s Fox River with lip tumors, demonstrating the presence of aromatic hydrocarbons used for dyes, pharmaceuticals, and agro-chemicals which are known carcinogens. Courtesy of Dr. Paul C. Baumann, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

URBANIZATION

AND THE SYSTEMIC RECLAMATION OF THE GREAT LAKES WATERSHED

Although deindustrialization and decentralization are dominant motifs of the Rust Belt, what is often marginalized is the long-term legacy of industrial economies. The depletion of cheap resources, the depopulation of factory towns, the decrease of tax revenues, and the failure of urban infrastructure epitomize that legacy. Most notorious are environmental after-effects across the region, including oil fires on urban rivers in Cleveland, Toronto, and Chicago; over-fertilization and sewage discharge of Lake Ontario and Lake Michigan; algal blooms from eutrophication in Lake Erie and Lake Ontario;40 and the mercury contaminations from industrial discharge that closed fisheries on Lake Superior, Lake Michigan, and Lake Huron in the 1980s.

The total impact of industrial effluents, chemical dumps, and urban floods was largely invisible until a quarter-century after the Manufacturing Belt passed its peak. Three events within seventeen years defined the ecological enlightenment amidst the fallout of mass-industrialization: Hurricane Hazel in 1954, the Milwaukee River point-source discharges in 1967, and the Love Canal Incident in 1971. With the respective efforts, activists across the region like landscape architect Michael Hough, the Milwaukee Sentinel daily newspaper, and the Love Canal’s Lois Marie Gibbs, a series of milestone legislative actions ensued: the Conservation Authorities Act in 1946, the Environmental Protection Agency of 1971, the Superfund Bill of 1980, and the Clean Water Act of 1977. Point-source separation of industrial effluents, encapsulation of chemical dumps, and planning of urban floodplains soon became underlying principles in the replanning of cities. Noncompliance and lack of enforcement threatens this ambitious objective,41 but the Clean Water Act has managed to cast light on a dark industrial age when Americans could no longer swim in major rivers like the Mississippi, the Potomac, or the Hudson.42 Reconsidered historically, ground and water contamination could no longer be ignored nor treated separately as it was before. It was now being understood regionally as a new systemic understanding of the effects of industrialization emerged.

Open, Complex Systems

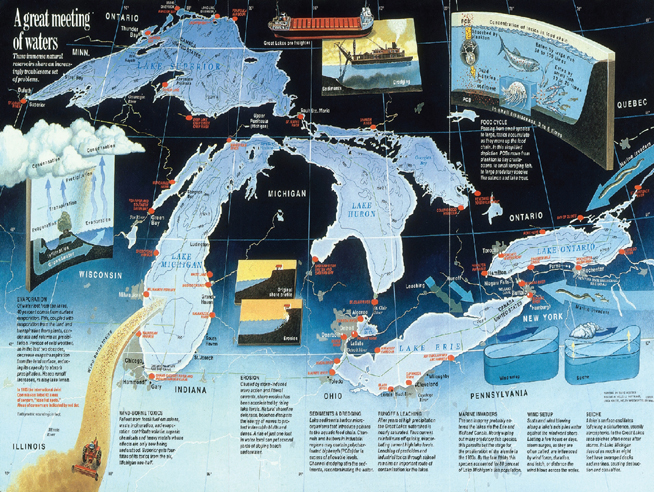

Map depicting the systemic representation of the Great Lakes region following the 1978 Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement that was signed by Canada and the United States to “restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the waters of the Great Lakes Basin Ecosystem.” Source: Ngs Labs/National Geographic Creative, Image ID: 23260

Crisis as Catalyst

Aerial view of the Humber River in Woodbridge during Hurricane Hazel in November 1954, subsequently leading to the Conservation Authorities Act. Source: Photography from the archives of Toronto and Region Conservation, 1954

De-Engineering and Replanning

One of the most influential organizations to emerge from Hazel’s aftermath is the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA). Founded on the urban ecological tenets of landscape architect Michael Hough in the late ′50s,43 the TRCA has grown over the past fifty years to become an influential think-tank-action-group whose name is synonymous with watershed management, ecological planning, habitat restoration, business financing, and urban development. This nonprofit, quasi-governmental organization now mandates five major watersheds draining into Lake Ontario which support the 5.5 million people of the Greater Toronto area, while innovating strategies of stormwater management and watershed based conservation.44 With the abundance of available permeable surface area and green-leaf coverage in suburban areas, as well as their suitability for change, the ultimate aim is to reduce loads on stormwater systems while contributing to groundwater recharge. From the continuous flood events in Ontario to the ongoing flooding of the Farnsworth house in Illinois, the challenge of urban flooding has yet to be resolved in any comprehensive way and will persist. Larger and larger urban agglomerations, aging sanitary sewers, leaking water supply lines, and the increasing frequency of rainstorms will need to be addressed using integrated management measures that closely correlate urban patterns with the dynamics of hydrological systems.

Landscape as Megastructure

Plan and detail of the 300-kilometer Greenway Strategy on the northern shore of Lake Ontario by David Crombie and Suzanne Barrett. The project was conceived in response to growing urbanization across the lake and in relation to distinctive patterns of ravines, watersheds, glacial geology, and groundwater resources. Source: Waterfront Regeneration Trust, 1995 (below), OPSYS adapted from Municipal Affairs & Housing 2008 (left)

Reclamation and Remediation

Addressing the divide between economy and ecology, a massive remediation program in the Great Lakes region was spearheaded by the International Joint Commission (IJC) in the late 1980s, addressing the impacts of discharges and diversions, floods and droughts, and contamination and cleaning. With its mandate to advise on the use and quality of boundary waters in Canada and the United States, the commission addressed three of the most pressing challenges in the Great Lakes: combined sewer overflow, nutrient overloading, and sediment contamination. Redressing the historical legacy of shoreline industries, the purpose is to reclaim the “chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the waters of the Great Lakes Basin Ecosys-tem.”45 As the principal source of contamination in Great Lakes rivers and harbors, polluted sediment created by decades of industrial and municipal discharges historically limited remediation and redevelopment efforts by virtue of its geographic magnitude.46 The IJC has since initiated remedial action plans for forty-three priority sites throughout the region. The binational program uses multilateral funding and cross-border legislation to accelerate cleanup and redevelopment of the most contaminated sites, mostly harbors, in the downstream region.47 Since bioremediation alone cannot solve the challenge of brownfield redevelopment, the effect of new, integrated regional economies offers a significant model for the reuse of land. At this scale, remediation costs can be offset by overall returns from productive land redevelopment across multiple sites. For the first time in the history of the Great Lakes, the collective objective of an economy based on clean freshwater has become a public regional imperative. At the turn of the twenty-first century there is a contemporary urbanization of waterfronts in the Great Lakes and cities such as Chicago, Toronto, Hamilton, Sudbury, and Detroit are in the vanguard. Public works projects by Kathryn Gustafson and Piet Oudolf in Chicago or by Field Operations, West 8, and MVVA in Toronto can be seen as the inception of a systemic, regional reclamation project in its infancy.48 Its economy is its ecology.

Regional Register

Icon of modernism, the Farnsworth House designed by Mies van der Rohe and built in 1951, succumbs to a record-breaking flood from the Fox River but survives as a geo-physical registration of perennial rain levels in the region. Source: ©2008 Landmarks Illinois, National Trust for Historic Preservation

Infrastructural Coupling

View of stormwater interceptor tank doubling as public space promenade on the edge of Lake Ontario, on Toronto’s waterfront. Source: West 8/Adriaan Geuze, 2010

SUB-URBANIZATION

AND SUPER-URBANIZATION

Horizontal spread and peripheral expansion remain the predominant forces that restructure towns and cities across the Great Lakes, but citing depopulation and outmigration from city centers as the only causes of economic decline during the second half of the twentieth century is flawed. Nationally, population statistics show that while the population of the US was increasing, the Great Lakes region remained nearly constant, with just 1 percent growth.49 What really occurred was regional population dispersal through inner city exodus.

Culturally and economically diverse, metropolitan areas such as Chicago and Toronto kept growing, but mostly on their peripheries. Access to a multitude of urban, public, and high-quality services—education, mass transit, and health care—supported by essential infrastructures of waste, water, food, transport, and energy made them particularly attractive to a younger, knowledge-oriented generation. The transition from an industrial economy to an urban economy also involved a shift from massproduction and heavy equipment to light manufacturing and to just-in-time logistics.50 Large centralized industries of macro-production made way for a decentralized regional pattern of micro-production, requiring new land uses and public services.

The only logical course of action for nearby factory towns was to downsize. Regionalizing their services, distributing densities, and tapping larger urban economies became possible.

Mayor Jay Williams has been testing the potential outcome of downsizing in Youngstown, Ohio. With plant shutdowns by Republic Steel and Youngstown Sheet & Tube Company over the past twenty years, the city is facing major fiscal deficits inherited from oversized infrastructure, abandoned properties, and countless miles of asphalt roads to maintain. Derelict buildings are being razed, underground utilities cutoff, lands banked, and industrial districts rezoned; back taxes are exchanged for land stewardship and roads are ripped up or blocked out. Remaining lands are amalgamated for urban agrarian use, parkland, or water uses.51 Former industrial land uses are overlaid with new productive functions, bypassing the traditional rezoning process. Counter-strategies are modest but effective. The Mahoning River was once the sewer of Youngstown’s steel mills; now it serves as the backbone of an emerging corridor of light- and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises.52

Echoing Ely’s approach to land economics, Williams’s decommissioning strategy suggests a general process of de-urbanization, where industrial un-development and land unincorporation will ultimately reduce the tax burden on citizens and maintenance burden on the public works department. “Instead of capturing its industrial past, Youngstown hopes to capitalize on its high vacancy rates and underused public spaces to become a thriving bedroom community serving Cleveland and Pittsburg both of which are 70 miles away.”53 Suburbanization may be Youngstown’s imperative.

Beyond the City

Paramount to the understanding of this geographic phenomenon is the reconsideration of the Old World notion of the city as the locust of urban activity. Whereas the categorically European notion of the city relies on theories of smallness, compactness, proximity, and density, the North American logic of urbanization relies upon the exigencies of scale, distance, logistics, openness, and horizontality. This counter- intuitive view was explored in greater depth by French geographer Jean Gottmann in the late 1950s.

Studying the logic of a rapidly spreading pattern of urbanization across the northeastern region, Gottmann later collected his findings in a book originally titled Megalopolis: The Urbanized Northeastern Seaboard of the United States, in which he called for the rethinking of the Old World notion of the city altogether:

“[W]e must abandon the idea of the city as a tightly settled and organized unit in which people, activities, and riches are crowded into a very small area clearly separated from its non-urban surroundings. Every city in this region spreads out far and wide around its original nucleus; it grows amidst an irregularly colloidal mixture of rural and suburban landscapes; it melts on broad fronts with other mixtures, of somewhat similar though different texture, belonging to the suburban neighborhoods of other cities.”54

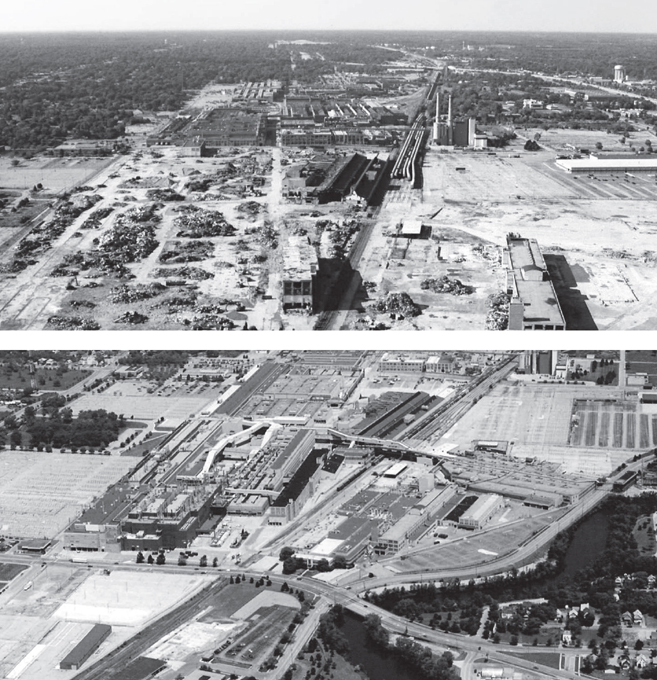

Post–Fordist Landscape

Demolition of “Buick City” in Flint, Michigan, one of the largest automotive manufacturing complexes in the world, originally built in 1904, bought by General Motors, and shut down in 1999. Source: Leonard Thygesen, 1993/2002

New World

Jean Gottmann’s map of the northeastern megalopolis, representing a thoroughly new and unprecedented pattern of urbanization, in complete contrast to the centric, compact configuration of the European city. Source: American Geographical Society (Dr. Herman Friis) ©1961 in Jean Gottmann, Megalopolis (New York, NY: Twentieth Century Fund, 1961)

Grounded in geography and economics, Gottmann’s observations characterized the Northeastern Seaboard of America from Boston to Washington as an urban landscape with a decisively distributed, horizontal structure. Anticipating Gottmann’s future work, Geddes observed in 1915:

“That the expectation is not absurd that the not very distant future will see practically one vast city-line along the Atlantic Coast for five hundred miles, […] the great lakes, with the immense resources and communication which make then a Nearctic Mediterranean, have a future, which its exponents claim may became world-metropolitan in its magnitude.”55

These findings proved useful a decade later when the Greek architect and planner Constantinos Doxiadis attempted to map out the future of the Great Lakes region. Prefiguring centrally in his diagrams, the basin of the Great Lakes could be understood as an urban megastructure.56 Commissioned by the private regional electrical utility Detroit Edison Company, the project involved a three-year study on the pattern of urbanization of Great Lakes cities. Despite Doxiadis’s firm commitment to ekistics, the study of human settlements, his exclusive focus on the urban Detroit area overlooked the fate of the region.

Based on double-digit growth from postwar projections, the study assumed a steady and ambitious growth for Detroit, the region, and the continent.57 Exacerbated by a worldview which characterized urbanization as a universal crisis, the results of Doxiadis’s three-volume study were skewed: downward economic trends were overlooked, sociopolitical events such as labor disputes and union riots were ignored, and the Canadian side of the Great Lakes was sometimes left blank. His plans overemphasized centralized development. For example, the 1965 plans projected populations of 15 million for Detroit, 75 million for the Great Lakes area, and 400 million for North America by the year 2000.58 Overestimates would have boded well for the electricity authority since they fed the illusion of increasing demand for electrical energy and distribution infrastructure.

Reliant upon conventional measures of city census and data inventories, Doxiadis’s plan turned out to be a false positive, both regionally and nationally. Revisiting his precedent setting analysis of the northeast megalopolis, Gottmann updated his findings with startling results:

“Twenty years ago, the patterns of urbanization along the Great Lakes did not seem to be truly comparable in density and function with the Northeastern Seaboard megalopolis. A vast chain of metropolitan regions was forming there, especially on the American side of the lakes […] but with a looser structure and specialization in manufacturing production rather than in quaternary activities. Now a rapid evolution has taken place modifying the picture, and I am much inclined, even in my strict interpretation of the megapolitan concept, to recognize its rise here. The Canadian sector of the Great Lakes Megalopolis is probably, in the present circumstances, the most megapolitan indeed by its rapid development of transactional activities, and by its national and international role as a hinge and as an incubator. […] The Great Lakes Megalopolis is probably the largest in area of the present megapolitan systems, […] envisaged as extending from the city of Quebec, in the East to the metropolitan area of Milwaukee in the West, including along that axis such great agglomerations as Montreal, Ottawa, Toronto, Detroit, Buffalo, Cleveland, and Chicago […]comparable to other systems in the world including megalopolis of northwestern Europe (Amsterdam to the Ruhr), the Rio de Janeiro-São Paulo complex in Brazil and the urban constellation in Mainland China centered on Shanghai.”59

Doxiadis’s Dream

The speculative boundaries of the growing Great Lakes megalopolis from the hand of ekistics guru-cum-world-planner Constantinos A. Doxiadis. Source: Emergence and Growth of an Urban Region (vol. 1), 1970, p.109, Fig.63 © Constantinos and Emma Doxiadis Foundation

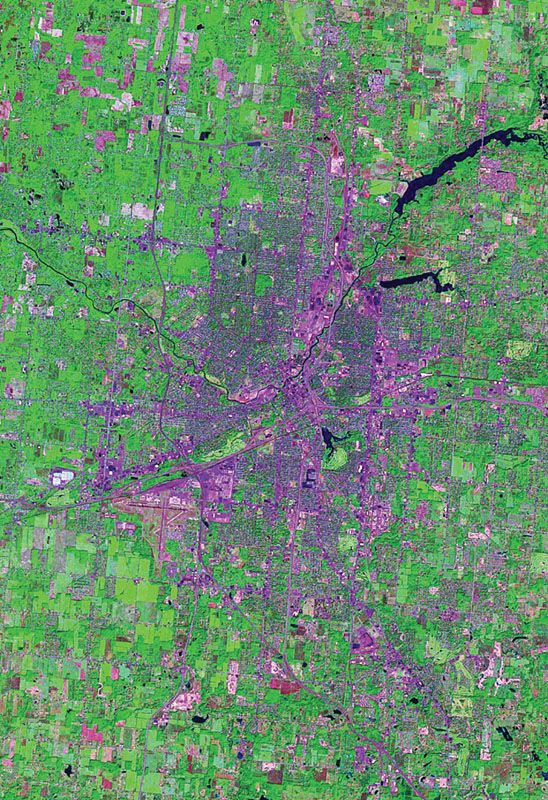

Banking on Land

Satellite image of Flint, Michigan, home to the former “Vehicle City” and now the seat of the first land-bank authority in the state reorganizing abandoned, contaminated land with new fiscal and ecological measures associated with the Flint River watershed (running through center of the image, through the city) and Genesee County. Source: Landsat GeoCover 2008, data courtesy USGS

But he cautioned against facile, simplistic generalizations about urban regions:60

“The megaregion, as it is becoming today, is not a larger, or bigger city. Nor is it merely an amalgamation of cities and metropolises growing together […] [this emerging pattern] is not simply urban growth on a bigger scale; it is rather a new order in the organization of space and in the division of labor within society, a more diversified and complex order, allowing for more variety and freedom.”61

GEOGRAPHIC URBANIZATION

Numerous gains can be made in the collective characterization of cities as urban regions.62 Although the urbanized region of the Great Lakes might appear today as an unplanned collection of large, industrial metropolises sprawling haphazardly out of control, there is a prevailing logic to its morphologies and patterns of change. In the context of the often-discussed pattern of urban sprawl across the Great Lakes, the region has seen a net population growth as a whole, even as many Rust Belt cities have dramatically declined in size. Conditioned by a complex hydrology, this landscape of urbanization is best understood as an unfinished process, an incomplete region.63

Indicative of this nascent process are three notable structural transformations that provide evidence of ongoing spatial change: land banking, energy harvesting, and greenhouse growing.

Land Banking

There are between 30,000 and 50,000 brownfield sites across the Great Lakes states that pose obstacles to urban redevelopment and threats to groundwater resources. So far, local governments have been unable to manage brownfield sites or prevent blight due to the accumulated effects of subsurface contamination, outdated fiscal legislation, inflexible zoning policy, and financial accountability. Michigan is an exception and an experiment. The state has recently enacted new legislation with revisions to the 2004 Brownfield Redevelopment Financing Act and created the Genesee County Land Bank Authority to address the erosion of property values throughout the Saginaw Bay watershed in northern Michigan. Land banking involves the acquisition of abandoned and foreclosed properties through a series of unique measures: vacant lot aggregations, surface maintenance regimes, land management strategies, demolitions, reconstructions, sales, property transfers, foreclosure prevention, and alternative zoning mechanisms. Land banking along the Flint River in northern Michigan is achieving several objectives. First, it effectively reclaims isolated watershed lands and forms a hydrological network. Second, it reduces loads on existing systems and builds up the capacity for self-sustenance. Third, it elicits contemporary forms of development, stimulating emerging light industries such as mini-mills, mini-smelters, mini-farms, or micro-breweries.64 In turn, fiscal benefits are passed down from county, to municipality, to taxpayer. Today, the Land Bank Authority manages more than 4,000 properties and its flagship is the City of Flint, ironically the graveyard of General Motors and United Auto Workers.65 As the envy of real estate property management, Flint is becoming a prototypical model for land banking and of regional land reclamation across the US.66

Farming Energy

Deregulation during the agricultural bubble in the 1980s led to an unusually high concentration of large agri-businesses in the region. Vertically integrated corporations took over major segments of the foodshed, across regions of production within fifteen years, ploughing half a million small independent farmers and ranchers under and emptying rural communities.67 Destroying regional economies, the predatory incorporation of the industry took over major sectors of production and distribution, from seedlings to supermarkets. Corporate dominance, which relies on economies of scale, is now being put to the real test. The rise of oil and gas prices in the 1970s, the aging of nuclear power plants and coal-fired power plants in the 1980s, and the rising of commodity prices in the 1990s are now casting doubt upon the reliance on the importation of what used to be cheap oil resources from the Middle East or polluting coal from the Appalachian range. From this shift, hybrid agrarian patterns of development are capitalizing on idle farmland to combine energy generation with crop cultivation. Sprouting from Michigan’s farmland are crops of wind turbines in rural areas on the southern shoreline of Lake Huron, with its high winds and low densities.68 Using a loophole in fiscal policy for implementation, John Deere Energy Renewables—the company that revolutionized farming in the late nineteenth century—is now building the first utility-scale wind farm in Bad Axe, Michigan.69 The 32-turbine, 52.8-megawatt commercial wind project spreads across five square miles of agricultural fields and produces enough power to supply 15,000 homes. The project is the result of a unique public–private partnership between John Deere, the Detroit Edison Company, and the county. However, the beauty of the project lies in the cooperation across this new agro-energy shed: farmers lease land to the power utility for the erection of towers, leaving the cropland of beets, beans, cereals, and grains undisturbed. In turn, counties collect revenues from building permits and turbine construction, and townships receive annual taxes. The anticipated long-term benefit is that the value of farmland will increase steadily. Another 280 wind turbines are now planned across the county over the next two decades and, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency, the estimated potential of 100,000 wind turbines on the shorelines of the Great Lakes state could meet one-third of America’s power needs.70

Cash Crop

The Harvest Wind Farm in Bad Axe built by John Deere Energy Renewables on land leased from cooperative sugar beet farmers, the first commercial-scale public-utility wind field in Michigan. Source: ©2008 Don Coles, Great Lakes Aerial Photography

Under Glass

The fast-paced growth of the Leamington-Ruthven-Kingsville greenhouse region of Ontario. Photo couresy of GITC Agro

Greenhouse Effects

The most significant uses of fresh water in the Great Lakes are for power plants, drinking water, irrigation, and livestock.71 Including withdrawals for industrial production, water usage is increasing by 3 to 5 percent year-on-year due to global warming. From an agricultural perspective, however, the region is a winner in the climate change game and the Leamington-Kingsville area is at the forefront. Located in Ontario, on the north shore of Lake Erie along the 42nd Parallel, the “Tomato Capital of Canada” is now the leading greenhouse region in North America with the highest rate of start-ups in Canada, doubling between 2000 and 2005 in the Niagara region alone. Growers of the principal crops of tomatoes, cucumbers, and peppers are diversifying into tender fruits, vine-ripened vegetables, and specialty flowers cultivated in controlled hydroponic conditions which in turn limit pesticide inputs and runoff into nearby Lake Erie.72 Arable lands, increasingly warm weather, and an abundance of freshwater and sunlight are further contributing to the diversification of its cultures. With $1 billion in farm gate value, Leamington’s greenhouse acreage exceeds that of the entire U.S. greenhouse industry. This emergent agro-economy follows the blossoming of other bio-industries across the Great Lakes, including viticulture (wine-making and grapevine crops), silviculture (timberlands and dimensional lumber), and floriculture (greenhouses and nurseries). Bio-industries are extremely competitive in comparison to conventional heavy industry. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, floriculture—including plants for bioremediation and bioengineering— has been outpacing all other major commodity sectors in sales growth since the early 1990s.73

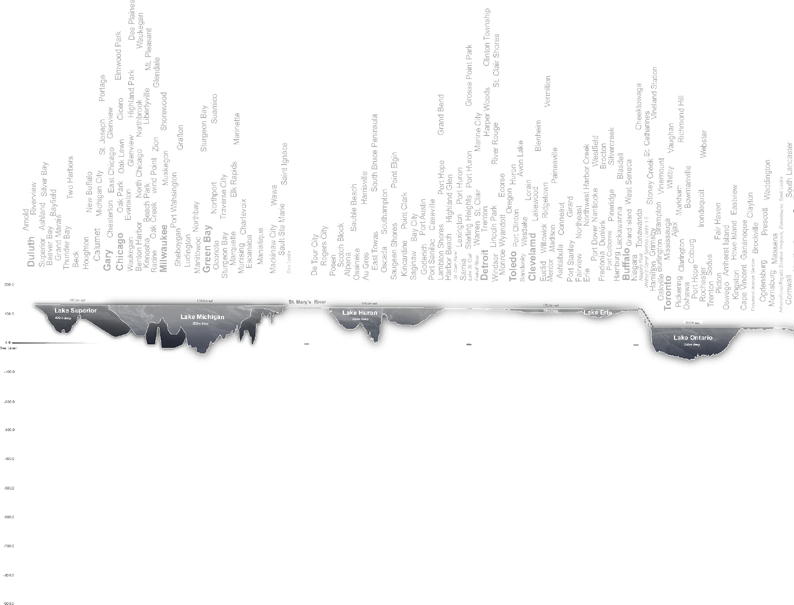

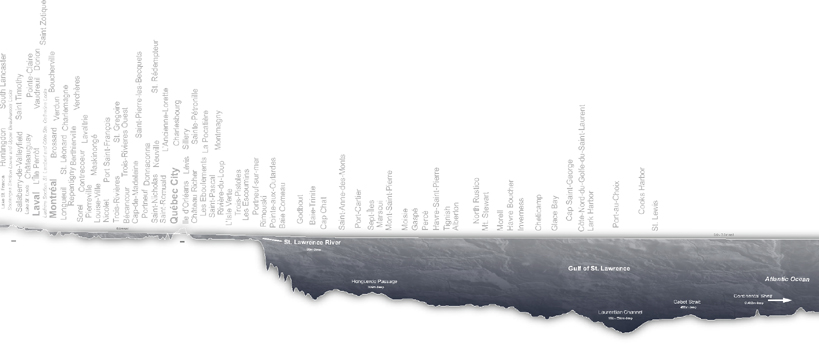

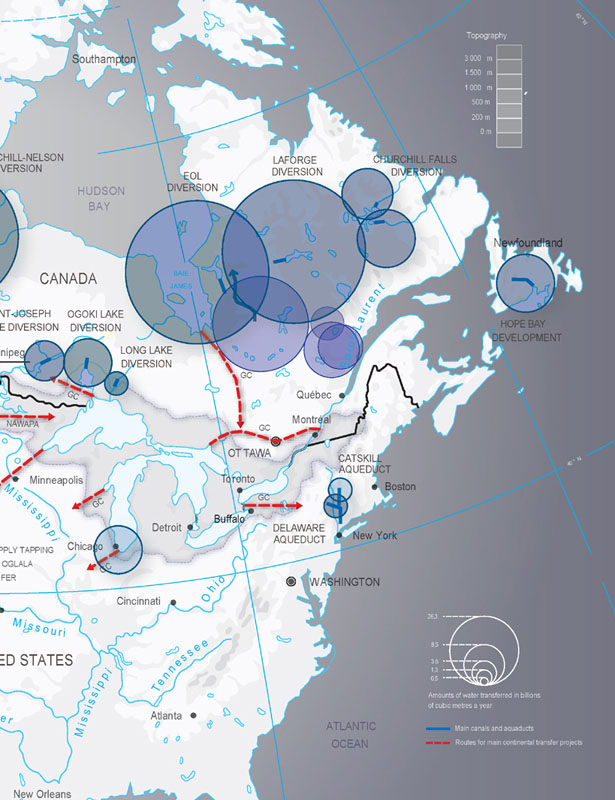

Estuarine Urbanism

A cross-sectional view of the Great Lakes displaying an urban agglomeration of cities from Duluth to Glace Bay, home to approximately 40 million people dependent on the 20 quadrillion liters of water flowing from Lake Superior to Lake Ontario to the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Source: Adapted with data from NASA–NOAA–United States Geological Survey – Statistics Canada–Geode–St. Lawrence Seaway System, 2009

Estuarine Urbanization

Spanning more than 1,200 kilometers, the distribution of cities, towns, and communities across the five major water bodies of the Great Lakes with more than 30 million people who share the same water. Diagram: OPSYS

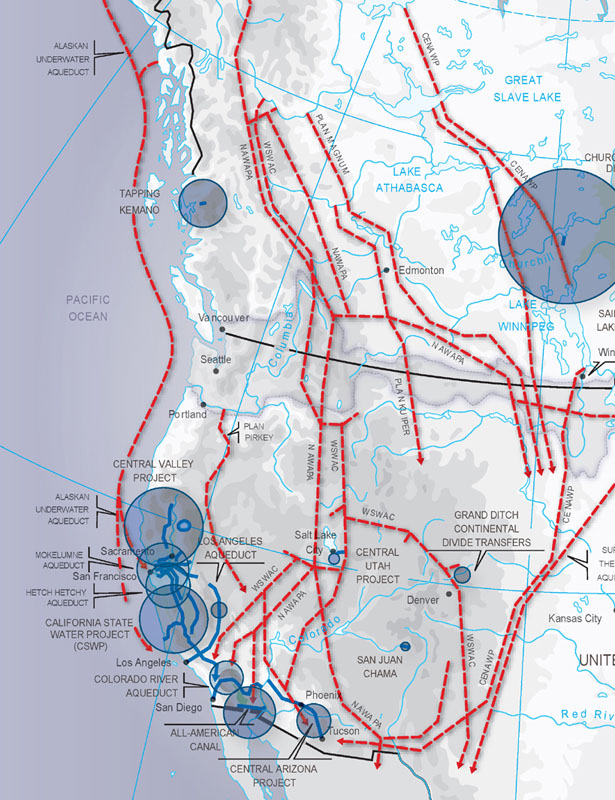

Pipe Dreams

Great Lakes water diversions in the context of current and future inter-basin projects across North America, the source of looming cross-regional politics along the longest, most undisputed border in the world. Source: Frédéric Lasserre, Continental massive water diversions. Present infrastructure (2007) and main projects, 1951–2001. Adapted by F. Lasserre from Frédéric Lasserre, Major Water Transfers: Tools of Development or Instruments of Power (University of Québec, 2005) and Monde Diplomatique (March 2005)

Watershed as Infrastructure

The concurrent development of land banks, wind farms, and greenhouses demonstrate the potential of new strategies that engage the systemic integration of urban infrastructure with biophysical resources. As countermeasures to the predominant challenges of the Great Lakes region, including water pollution, land abandonment, and the farming slump, these strategies usher in an era of regional economic regeneration where large centralized massproduction industries are being supplanted by distributed, networked patterns of production, cultivation, and management.74 Although the long-term effects of this shift have yet to be understood, what remains clear is that the transition from a globally based carbon economy to a regionally-based carbohydrate ecology and economy is underway.75 Opening new territories for renewal and new surfaces for occupation across the region, these developments demonstrate the capability of regional landscape strategies to address several challenges of various complexities simultaneously. This is where design becomes instrumental, moving across varying scales of intervention from planning to engineering, transcending conventional boundaries of private and public interests. From this vantage point, the new design imperatives are found in the basic processes and essential services that support urbanization, including the integrated ecologies of water, energy, food, mobility, and waste, which have traditionally been treated as separate components or separate districts in municipal planning. Through the bundling of multiple ecological services, strategies can achieve greater economies and ecologies of scale.76,77 Forming a geographic field, these urban–regional strategies can be considered synergistic, self-perpetuating, and self-maintaining. It is at this precise moment that the region becomes infrastructural.78

Bodies, Commons, Partitions

Geopolitical map of the international territorial waters layered with state-provincialcounty jurisdictions across the transnational watershed boundary of the Great Lakes region. Diagram: OPSYS adapted with data from International Joint Commission-United States Geological Survey–Environment Canada

Super-Regional Urbanization

Geospatial context of the Great Lakes with the concentrations and extents of urban patterns across the Americas. Diagram: OPSYS, with data from NASA–United States Geological Survey: 2008

Urban Region as Landscape

Emerging from a long, dark history as the sewer of North America, the Great Lakes region may be understood as a macrocosm of change, a case study in the historical transformation of the continent. Land transformations during the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries present compelling evidence that, as a large, complex, collective system of biophysical and hydrodynamic processes, the Great Lakes effectively preconditions industrial operations and sustains urban economies.

Retroactively, the multiple characterizations of the Great Lakes as a region reveal an underlying landscape of persistent geoeconomic and biophysical significance that warrants more depth and greater consideration for the future. Economically, the region ranks second in the world with a $4.6-trillion gross regional product. It represents two-thirds of North America’s purchasing power, rivaled only by the United States as a whole and larger than the economies of Japan, China, Germany, and the UK.79 Demographically, the 45 million people who live and work in the region represent 30 percent of the combined Canadian-American population. Geographically, the population is urban and decentralized, bordering a coastline of more than 15,000 kilometers. Politically, the region spans eight states and one province, including 447 counties located in two different countries sharing the longest, least-disputed border in the world. Hydrologically, the population draws on a nearly 500,000 square-kilometer watershed—ten times the size of the Netherlands or Belgium—as its sole source of fresh water. The urban economy of the Great Lakes is thus inseparable from its Nearctic ecology.

Notwithstanding the demand for staple resources of lumber, taconite, and aggregates, the projected 3 to 5 percent population increase is an indicator that the region will continue to attract considerable domestic and foreign interest in the form of immigration and investment. However, due to the scale of processes and range of operations that the region can support, its ecology will be, as it always has been, an ongoing setting for conflicts and contradictions.80 In contrast to the regionalism of the 1960s and 1970s which sought to reconcile differences and make cohesive what was inside the region, contemporary characterization of the process of regionalization provides room for complexity and contradiction, association and disconnection. With increased diversions and excess abstractions, reserves of fresh water will be under strain as consumption continues to exceed replenishment by a factor of 6 to 9;81 water politics will be at the epicenter of these challenges.

Nevertheless, ideological debates will have to yield to a more factual and sophisticated discourse.82 Historical oppositions between basic concepts—city vs. country, low-density vs. high-density, local vs. global, industry vs. agriculture, native vs. exotic—are quickly becoming obsolete in favor of new complexities, new formulations, and new synergies.83 Whether we refer to the spread of sea lampreys in the first half of the twentieth century84 or the annual restocking of 4 million fish in Lake Ontario or the more than one hundred introduced species found across the Great Lakes today, the transmutation of the ecology of the Great Lakes is anything but natural, nor can we revert to conventional means of natural resource conservation. Regionalization requires us to move beyond the conventions of conservation and preservation, which entail the separation between development and resource areas, to focus on the expansion and prolongation of living systems as prime objectives of design in conjunction with extra-national forces.85 Whether by planning, policy, or engineering, this is the contemporary regional design imperative. The formation of environmental protection agencies, watershed conservation authorities, and remedial action plans, at the close of the twentieth century are some of the initial drivers of this current change, though considerable efforts are required to fully exploit this paradigm shift in the present century. The spaces and slippages between states and systems, between political units and hydrological basins, will necessarily have to yield and negotiate alternating conflicts at times, while learning to maximize and capitalize on shared zones. The de-territorialization of the state/system dichotomy thus opens a lens on urban regions that enters into contemporary society, no longer as subdivision, container, or “territory” as Mumford associated,86 but as landscape which “challenges the entrenched geographical assumptions of mainstream approaches to state space.”87 Simultaneously, it acknowledges the pervasiveness of globalization but recognizes its geopolitical unevenness, inequality, and incompleteness. As such, in this variegated geopolitical terrain, globalization may potentially be better understood as a “myth,” and that all “globalization is about regionalization,”88 constantly moving across seemingly fixed borders.

Brave New Ecology

A bighead carp caught in the upper reaches of the Mississippi River. Introduced to fish farms in America during the 1830s and migrating north to the Great Lakes, this vigorous species thrives in heavily polluted waters and can jump up to 10 feet out of the water. The species shown here, a bighead carp, weighed 92.5 pounds, was 62-inches-long and had a 30-inch girth, establishing a new world record. Source: Darin Opel, Illinois Bowfishers Club, 2008

Extra-National Economy

Comparative view of the GDP (gross domestic product, USD billions) of the Great Lakes–St. Lawrence region in comparison to the top twenty economies across the world. Diagram: OPSYS adapted from World Bank–World Business Chicago–World Economic Forum, 2011

The refocusing on new regions and new territorialities, therefore relies on the rescaling and redrawing of biophysical substructures in tandem with geoeconomic super-structures. As dynamic configurations and active morphologies, the boundaries of surface waters, the network of biotopes, the bathymetry of lake bottoms, the contours of cities, the attendant infrastructures, and the flow of resources around the Great Lakes are fundamental to this shifting optic. As measures of intelligence, the mapping of inter-regional flows and extra-political reciprocities provide a base to register and effect change over time. Instead of a single, bounded, closed, homogeneous environment,89 the regionalization of the Great Lakes can cast light on the network of endogenous (internal) and exogenous (external) processes at work.90 When viewed telescopically at different resolutions and scales, across different times, and multiple boundaries, the region can then be understood as a system of systems.91

In this expanded field, the regionalization of design practice can consequently transcend conventional spatial boundaries, disciplinary territories, and political ideologies. Design can be liberated from the straitjacket of shortsighted bureaucratic time scales and the confinement of jurisdictional site boundaries. Capitalizing on geopolitical cleavages, design can unearth and propose mutual, cooperative, interdependent, and synergistic strategies at large scales that spin off inter-regionally. Consequently, design can be informed by continental geography and global ecologies and by the superintendence of time. The physiographic and political regionalization of urban areas thus moves beyond that of mere background for planning or mere unit of development. As planning tactic and design strategy, regionalization becomes instrumental and infrastructural, setting the precedent for landscape reclamation and landscape urbanization across the continent and other industrialized regions of the world, from the Americas to Asia to Africa.

From the 40 million acres of cutover land to the management of more than 20 quadrillion liters of fresh water in its watershed, the engagement of the Great Lakes as a complex landscape is pressing. If freshwater is the oil of the twenty-first century, then the agency of urban regions—as new geographies of contemporary urbanization where political states, technological infrastructures, and natural systems overlap—is and will continue to be of critical and contemporary significance, globally.

Originally published as “Regionalisation: Probing the urban landscape of the Great Lakes Region” in JoLA - Journal of Landscape Architecture (Fall 2010): 6–23.

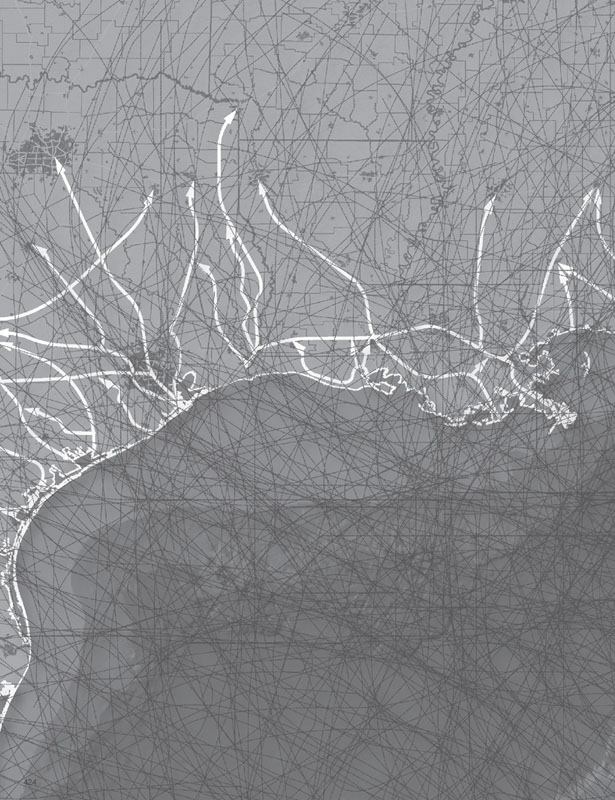

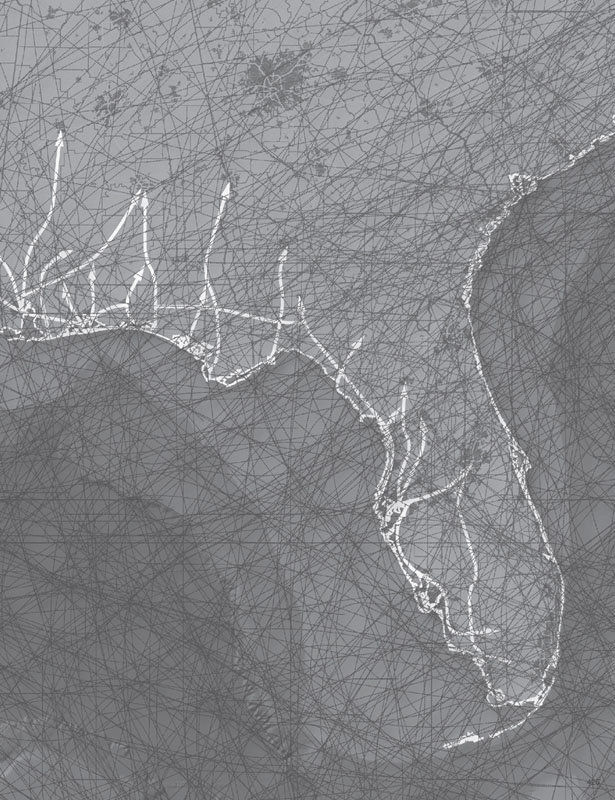

Coastal Contraflow

Historic paths of hurricane and subtropical storms from 1857–2011, juxtaposed with stratregic patterns of evacuation from landfall regions along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico toward designated twin cities further inland. Diagram: OPSYS

Notes

1. Lewis Mumford, The Culture of Cities (New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1938): 306.

2. Patrick Geddes, Cities in Evolution: An Introduction to The Town Planning Movement and to The Study of Civics (London: Williams & Norgate, 1915): 49.

3. “Chicago’s Canal and the Lakes,” The New York Times (January 3, 1897).

4. As in the case of Chicago, the development of geographic shortcuts between water bodies and across regional divides explains the birth of several cities throughout the Great Lakes. The city of Toronto, for example, whose name is derived from the Huron/Iroquois passage or portage, was a shortcut from Lake Ontario to Lake Huron, making it a strategic regional outpost for trade and transportation.

5. The annual death rate from diphtheria, cholera, and typhoid fever ranged between 500 and 2,000 for most of the nineteenth century. Typhoid fever was virtually eliminated by 1917 with chlorination of the water supply. Chicago Department of Health, General and Chronological Summary of Vital Statistics, Annual Report 1911–1918, Reprint Series No.16 (Chicago, IL: The Department of Health, 1919): 1424.

6. Ibid.

7. Missouri’s 1905 suit against Illinois to end the diversion was unsuccessful, but the Supreme Court placed limits of water diversion starting in 1925. See Stanley A. Changnon and Mary E. Harper, “History of the Chicago Diversion,” in The Lake Michigan Diversion at Chicago and Urban Drought, ed. Stanley A. Changnon (Mahomet, IL: NOAA Contract 50WCNR306047, 1994): 16B38.

8. From a hydrological perspective, the canal is extremely important as an emerging political and ecological issue of the future. The article by Jerry L. Rasmussen et al., “Dividing the Waters: The Case for Hydrologic Separation of the North American Great Lakes and Mississippi River Basins” speaks to that emerging reality. See Journal of Great Lakes Research 37 No.3 (September 2011): 588–592.

9. See American Public Works Association (APWA), Top Ten Public Works Projects of the Century 1900–2000, www.apwa.net/About/Awards/TopTenCentury.

10. See “Interbasin Water Diversions: a Canadian perspective” by F. Quinn, Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 42 No.6 (1998): 389–393.

11. See Empire and Communications by Harold T. Innis (Cambridge, UK: Oxford University Press, 1950).

12. See David R. Collins, Pioneer Plow-maker: A Story about John Deere (Minneapolis, MN: Carolrhoda Books, 1990), and Kimberley A. McGrath, World of Invention: History’s Most Significant Inventions and the People Behind Them (Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Research Group, 1990).

13. See The Making of Urban America by Raymond A. Mohl (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing, 1997): 93.

14. Ibid, 7.

15. The term super-urbanization stems from the use of the term “super-urban” and “super-city” in reference to fringes between city and suburban areas originally used by Benton MacKaye almost a century ago in The New Exploration: A Philosophy of Regional Planning (New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1928): 67, 69.

16. See Paul Sutter, “A Retreat from Profit: Colonization, the Appalachian Trail, and the Social Roots of Benton MacKaye’s Wilderness Advocacy,” Environmental History 4 No.4 (1999): 553–557.

17. One of P.S. Lovejoy’s most important contributions was a short, sweeping survey of the Cutover titled “Michigan’s Millions of Idle Acres” written for the The Detroit Free News, collected in P.S. Lovejoy and Fred E. Janette, Michigan’s Millions of Idle Acres—A Series of Articles Published in the Detroit News, May 24–June 4 (Detroit, MI: The Detroit News, 1920): 3–11.

18. See James Kates, Planning a Wilderness: Regenerating the Great Lakes Cutover Region (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2001).

19. Benton MacKaye, Colonization of Timberlands – Synopsis (Washington, DC: U.S. Forest Service, 1917) (Dartmouth College Library, The Papers of Benton MacKaye, Box 181, Folder 31): 3.

20. Early twentieth-century reclamation strategies echoed eighteenth-century colonization programs like the “Come to Detroit” campaign employed in the 1750s by the governor general of New France, who provided free incentives such as a spade, axe, sow, plough, seed stock, wagon, and a cow to attract newcomers to the swamplands in Michigan, lands that were unsuitable for cultivation by decades of rampant clear-cutting.

21. Ibid, 3.

22. Different from land planning or real estate development, land economics is a hybrid discipline crossbred from the fields of economics, politics, and agriculture. Land economics is based on a regional perspective for the effective reorganization and reuse of land over long periods of time, rooted in the preexistence of resources and the future of urban settlements.

23. See Richard T. Ely and George S. Wehrwein, Land Economics (New York, NY: The MacMillan Company, 1940): 382–383.

24. Alan Rabinowitz, Urban Economics and Land Use in America: The Transformation of Cities in the Twentieth Century (New York, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2004): 109.

25. The Broadacre City project was incubated at Taliesin during the 1930s and 1940s. Built in 1911, Taliesin was one of Wright’s studios located in Spring Green, Wisconsin, more than 150 miles away from Chicago. In the context of the agricultural crisis and increasing industrialization of the Chicago region, Taliesin was a reaction to and a rejection of the industrial city. for a more-detailed analysis of Wright’s urban–agrarian counterproposals, see Giorgio Cucci’s “The City in Agrarian Ideology and Frank Lloyd Wright,” in The American City: From the Civil War and the New Deal, ed. Giorgio Cucci, Francesco Dal Co, Mario Manieri-Elia, and Manfredo Tafuri (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1979): 143–292.

26. Despite his aversion to the centralized development of the industrial city, Wright maintained faith in its future potential. See Frank Lloyd Wright, The Living City (New York, NY: Horizon Press, 1958) and Sydney K. Robinson’s “Does Frank Lloyd Wright Belong in Chicago’s Architectural History? in Chicago Architecture: Histories, Revisions, Alternatives, ed. Charles Waldheim and Katerina Rüedi (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2005).

27. Wright, The Living City, 162.

28. David R. Meyer discusses this phenomenon with greater depth in “Emergence of the American Manufacturing Belt: An interpretation,” Journal of Historical Geography 9 No.2 (1983): 145–174.

29. See W. Bruce Bowlus, Iron Ore Transport on the Great Lakes: The Development of a Delivery System to Feed American Industry (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2010).

30. For events in the region revolving around the discovery of cheap taconite processing, see “Taconite Boom,” Time Magazine (April 28, 1952): 92–94.

31. For more information on the rise of Milwaukee, see Trading Post to Metropolis: Milwaukee County’s First 150 Years, ed. Ralph M. Aderman (Milwaukee, WI: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1987).

32. Joel Garreau, The Nine Nations of North America (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1981): 69.

33. By the late 1950s, decline was prevalent. Jane Jacobs identified early on the transformations occurring in cities across North America in Life and Death of Great American Cities (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1961), and subsequently in her follow-up The Economy of Cities (New York, NY: Random House Books, 1969).

34. See Pat Choate and Susan Walter, America in Ruins: The Decaying Infrastructure (Durham, NC: Duke Press, 1983).

35.Henry Ford (in collaboration with Samuel Crowther), My Life and Work (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1922): 192.

36.See Roland Jones, “As Detroit falters, Asian makers pick up speed: Toyota likely to surpass GM as world’s top carmaker; China lurks in wings,” www.msnbc.msn.com/id/10532121/.

37.Edward L. Glaeser, “Can Buffalo Ever Come Back?” City Journal 17 No.4 (autumn 2007): 94–99.

38.Jerry Slaske, “Choosing Milwaukee’s next top cop: Roughed-up Milwaukee needs results from its next chief,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel (August 19, 2007).

39.See Charlie LeDuff, “To Urban Hunter, Next Meal is Scampering By,” The Detroit News (April 2, 2009), www.detnews.com/article/20090402/METRO08/904020395.

40.During the 1960s and 1970s, several newspaper headlines read that Lake Erie was “dead” when, according to the U.S. EPA, the lake was actually more alive than ever. In fact, it was undergoing cultural eutrophication, an accelerated aging process by a large influx of nutrients (phosphorus) due to agricultural runoff and untreated wastewater effluent, mainly from industrial and household detergents. Evidenced in satellite aerial photographs, blue-green algae (Anabaena, Aphanizomenon, Microcystis, Cladophora) was blooming profusely in the western basin. See Larry Bentley, Environmental Education for Ohio, Biosphere 2000 Project, Environmental Science in Action: Lake Erie (EPA, August 2006).

41.For a thorough discussion of water policies in the Great Lakes over the past three decades, see John A. Hoornbeek’s “The Promises and Pitfalls of Devolution: Water Pollution Policies in the American States,” Publius 35, No.1 (Winter 2005): 87–114, and Jo Sandin, “30 Years Later, Water Cleanup Continues to Fight Current in Milwaukee Area,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel (2001).

42.Discharges and diversions are now regulated by the 1985 Great Lakes Charter and the subsequent 2005 Amendment.

43.In an article titled “The Urban Land-scape–The Hidden Frontier,” Michael Hough outlined how urban infrastructure could be conceived regionally and designed ecologically. See Bulletin of the Association for Preservation Technology 15 No.4 “Landscape Preservation” (1983): 9–14.

44.According to the Center for Watershed Protection, the full lifecycle cost of decentralized systems of urban water management is estimated to be three to five times less than conventional buried systems that are often found in inner cities. See Whitney Brown and Thomas Schueler, The Economics of Stormwater BMPs in the Mid-Atlantic Region—Final Report: an Examination of the Real Cost of Providing Stormwater Control (Ellicott City, MD: Center for Watershed Protection, 1997).