Bibliographic Notes.

Imaging Infrastructure.

Bibliographic note on image sources, permissions, and visualization methods1

“Resources appear, too, as shared visions of the possible and acceptable dreams of the innovative, as techniques, knowledge, know-how, and the institutions for learning these things. Infrastructure in these terms is a dense interwoven fabric that is, at the same, dynamic, thoroughly ecological, even fragile.”

—Louis L. Bucciarelli,

Designing Engineers, 19942

Behind each image lies an agency. Spanning different scales, this representational agency takes on many different forms and functions, indexing a series of different intentions and objectives. With varying vantage points, their orientations and alignments widely differ: from the individual and the institutional, the geometric to the geographic. Across time, these images—like their agency—are sometimes instant and immediate, or iconic and enduring. Anthropogenic or not, these varying scales reference new territories, establishing connections and links between different systems, and scenes, describing new orders and new organizations of land, from the personal to the planetary. Sometimes technocratic and specialized, or alternatively amateurish and unprofessional, these images offer a lens through which infrastructure could, and should, be understood, interpreted, and imagined.

How then can infrastructure be imaged? What does that image communicate? Who projects it, and who disseminates it? If infrastructure, as ethnographer Susan Leigh Starr proposes, is a “relational property,” “part of human organization,” “not a thing stripped of use,” and is also “ecological,”3 then these images reveal multiple relations and dimensions at which infrastructure can be expressed and understood. As a media of communication and medium of transmission, these infrastructural images are more than just vehicles and vessels, they “mean,” “carry,” and “question meaning,” […] “they imply underlying significations.”4 As visual equipment of the institutional or as instrument of the individual, these images then carry and convey changing identities through which we understand not only the nature of the interventions of political states, but the imagination of the state itself. If all infrastructure is historically biased, as shown here in this compilation of images, then its representation is necessarily politically biased.5 If organizations carry images, then the infrastructure is the image of that organization. Infrastructure-building is therefore also image-building.6 The visual study of infrastructure then, is a way to expose the complexity of systems that support urban life, the “invisible background” of modern life.7 Here, the media is not only the message, the media is the method. Conversely, the method of the book—visually and graphically dense—is in the media.8

Seen in time—either chronologically or syn-chronously—the historic delineation of infra-structural images throughout the book also reveals a series of telescopic and multidimensional scales. They are spatial, territorial, and organizational, defying the micro- and meso-scales by which technology, or large scale technological systems, is typically described. They expose the invisible conditions of the underground in relation to the surface—sections, cuts, and profiles, reclaiming rights to the subsurface and the reintegration of the underground with aboveground conditions. Like any media, they both imply and invoke bias that is personal and political. These biases are clarified, or sometimes obscured by the politics of pixels, in what Mark Dorrian refers to as the “politics of resolution,” and “resolution differentials,”9 in terms of who provides access to information, how it is shared, disseminated, or withheld.

Across time, these images redefine infrastructure’s agency in several ways. While public agencies may appear to be the most important providers of spatial imagery and archivers of information data since the nineteenth century (e.g. U.S. Geological Survey, NASA, Department of Transportation, Department of Agriculture, Library of Congress), privately acquired imagery has been increasing since the 1960s revealing a growing influence of the individual (in person or in corporation) and weakening power of the state (nation or state body). With the explosion of open source imaging and satellite imaging on demand since the 1990s, the production of spatial and territorial imagery has not only seen the explosion of new interfaces such as Google Earth or data-sharing platforms such as Wikipedia, they have enabled new levels of infrastructural exchange, engagement, and action with and on the ground.

Simultaneously, the imaging of infrastructure enables a form of recuperation of information and, more specifically, forms of representation, that otherwise would be left uncategorized or exteriorized by exclusive discourses on technology. One particular example is the work of ecologist Howard T. Odum, whose systemic, diagrammatic methodologies—for radioactive species, estuarine systems, military states—feature prominently throughout this volume given the “range of scales” they cut across, and the “processes of urbanization” that are clearly invoked, yet remain fundamentally “overlooked.”10

| Individuals | Researchers | Consultancies & Offices | Corporations & Firms | News/Media Publishers | Archives Foundations Libraries | State Agencies local, state, federal | Satellite Data Companies | International Organizations |

Scale and spectrum of agents, agencies, and organizations retrieving and producing data

As the frequency of infrastructural information continues to grow, aerial photography and topographic maps that were once produced every 5, 10, or 25 years are now available every month, every day, and even every minute. In 1968, after Apollo VIII circled the moon, a special stamp by the U.S. Postal Service marked “In the beginning, God…” memorialized one of the hundreds of photographs that astronaut Bill Anders took of the Earth from the Moon during the lunar orbit. Over three million stamps were issued, and the image was featured on the cover of LIFE magazine in 1969, seen and read by the eyes of nearly 3 million Americans. If then the representation of infra-structural images is being produced on a minute-by-minute and on-demand basis, could we not propose and envision a process through which the planning and implementation of infrastructure itself, and the development of an infrastructural eye, could go live?

Although the forms of representation (top views, side views, timelines) and types of imagery may vary from maps (territorial, navigational) and diagrams (patents, Sankey diagrams, organizational charts) to aerial photographs (Google Earth, Geo-Eye, kite photography) and organizational emblems (coats-of-arms, heraldic symbols), it is the range of techniques and methods of projection that cast important light on the infrastructural agency that is constantly at work: the jurisdictions of a transportation agency in the section of a curb or median barrier, the territorial authority of a federal agency in the satellite overview of regions, to the functional logistical diagram of a food terminal, the reformative actions of citizen collected data and cartography, to the historic emblem of an engineering organization that reveals ambition and aspiration. It is there in the transmission of images where the circulation and projection of political ideals—a state of states and system of systems—can be found and understood.

Finally, it is important to note that the image should not be confused with the individual or the institution themselves—and the “map” should not be mistaken for representing the “territory”11—the semantics and semiotics embedded in these images form visible connections and clear linkages with seemingly distant and disconnected subjects such as ecology, infrastructure, and territory.12 In the transmission of these different images and the deconstruction of their relations, we can begin to see the mapping and unfolding of different structures, states, and ultimately, new systems of power.

Notes

1. This note on the imaging of infrastructure was developed in parallel with the intensive, one-year process of image permissions and retrieval of sources for spatial imagery, that was led by Séréna Vanbutsele, a PhD candidate from UC Louvain currently completing her doctoral dissertation on spatial deterritorialization, titled “Le Déménagement Urbain” (“Urbanism as Evacuation”), 2016.

2. Louis L. Bucciarelli, Designing Engineers (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press: 1994): 131.

3. Susan Leigh Star and Karen Ruhleder, “Steps towards an ecology of infrastructure: design and access for large information spaces,” Information Systems Research Vol.7 No.1 (1996): 113. See also Susan Leigh Star, “The Ethnography of Infrastructure,” American Behavioral Scientist Vol.43 No.3 (November 1999): 380.

4. In his Rhetoric of the Image (1977), Barthes further explains: “All images are polysemous; they imply, underlying their signifiers, a ‘floating chain’ of signifieds, the reader able to choose some and ignore others. Polysemy poses a question of meaning and this question always comes through as a dysfunction, even if this dysfunction is recuperated by society as a tragic (silent, God provides no possibility of choosing between signs) or a poetic (the panic ‘shudder of meaning’ of the Ancient Greeks) game; in the cinema itself, traumatic images are bound up with an uncertainty (an anxiety) concerning the meaning of objects or attitudes. Hence in every society various techniques are developed intended to fix the floating chain of signifieds in such a way as to counter the terror of uncertain signs; the linguistic message is one of these techniques.” See Roland Barthes, Image/Music/Text (New York, NY: Hill and Wang, 1977): 44.

5. See Harold A. Innis, Empire & Communications (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1950): 196–197, and The Bias of Communication (Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 1964).

6. See Gareth Morgan, Images of Organization (Thousand Oaks, CA: Safe, 2006).

7. Paul Edwards, “Infrastructure and Modernity: Force, Time and Social Organization in the History of Sociotech-nical Systems,” in Modernity and Technology, ed. Thomas J. Misa, Philip Brey, and Andrew Feenberg (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003): 185–226.

8. See Marshall McLuhan’s “The Medium is the Message,” in Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (New York, NY: Signet, 1964): 7–23.

9. Mark Dorrian, “Google Earth” in Seeing from Above: The Aerial View in Visual Culture, ed. by Mark Dorrian, Frédéric Pousi (London, UK: I.B. Tauris, 2013): 301–302. See also Mark Dorrian, Writing on the Image (London, UK: I.B. Tauris, 2015).

10. Elizabeth Odum (widow of Howard T. Odum), in conversation (May 28, 2015).

11. See Alfred Korzybski’s dictum, “a map is not the territory”, in Science & Sanity: An Introduction to Non-Aristotelian Systems and General Semantics (Brooklyn, NY: Institute of General Semantics, 1933): 750, and Alessandra Ponte’s “Maps and Territories,” Log 30 (Winter 2014): 61–65.

12. For Michel Foucault’s writing on power and his influence on geography, see Claude Raffestin’s “Could Foucault have Revolutionized Geography?” (translated by Gerald Moore) in Space Knowledge and Power: Foucault and Geography, ed. Jeremy Crampton and Stuart Elden (Surrey, UK: Ashgate, 2007): 129–137.

Resolution Revolution

Comparative index of images showing the different scales, systems, and states that are invoked and implied by the media and method represented in this book, indicative of geography, agency, and history. From the Apollo VIII Mission that shared images of the Earth to the International Joint Commission that fought the pollution of boundary waters, these images reflect on the institutions and individuals that shape infrastructures and environments through their action through positions, policies, practices, and purposes. In turn, their strength lies in the multimedia nature of images themselves that expressively rethink scientific orders and authorities by including critical biases such as gender, family, diversity, biota, belief, even symbolism. Either i`n the rise of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in the middle of the nineteenth century or of landscape architects in the twenty-first century, we can see important changes and shifts in the scalar resolution of infrastructural images. More than just maps or mottos, signs or symbols, these images represent territorial motivations from the ground, in the kitchen of a suburban family home at Love Canal to the aquatic space of the great Lake Erie. Semiotically and semantically, as well as through resolution, they shape perception as past and future projections, making possible the imaging and imagination of change with and beyond the nation state. When displayed across time (diachronically) and in time (synchronically), the chronological timeline of images in this volume help to redefine infrastructure’s agency, beyond the nation state from the privatization of spatial imagery and information retrieval, to citizen cartography and live, grounded information.

Re-Reading Infrastructure

Bibliographic note and future readings on the converging fields of urbanism, landscape, and ecology

This selection of references provides a rereading of infrastructure through the lens of landscape and ecology. Responding to contemporary environmental pressures, resource economies, and mobile populations worldwide, this bibliographical note presents a series of influential views from a range of design disciplines to address pressing issues related to waste, water, energy, food, and mobility. Vis-à-vis the overexertion of civil engineering and the inertia of urban planning at the turn of the twenty-first century, the compilation reexamines canonical texts throughout urban his-tory—from Geddes to Gottmann, MacKaye to Mumford, Olmsted to Odum—with an aim toward elucidating the latent reciprocity between ecology and economy, infrastructure and ur-banism, growth and decline.

Organized as a sequence of cumulative subjects, each set of readings establishes a lineage of practices, projects, and processes that have been historically overlooked by an exclusively Old World view of New World urbanism. Using a reverse chronological order, the readings work backwards through the past hundred years when urbanization of the North American continent took on radically new proportions at the dawn of the twentieth century. To illustrate the magnitude of this change, each set of readings is paired with a selection of maps and timelines that chart urbanization as an unfinished process, further contextualizing the content within larger geographies, across broader timescales.

Challenging the laissez-faire dogma of neo-liberalist economics, Fordist forms of civil engineering, Taylorist methods of scientific management, and Euclidean planning policies that marked the past century, the compilation proposes an augmented agency for the design disciplines, where the field of landscape emerges as a base operating system for urban economies. Foreshadowing the preeminence of ecology for urban transformation in the present and future, the motive of this compilation is to open a contemporary horizon on infrastructure as design medium and to prime a clear, cogent discourse on the field of landscape as it becomes the locus of intellectual, ecological and economic significance.

The references are thus organized into two main groups of texts. The first group, “Preconditions & Processes,” outlines preliminary knowledge on urbanism, landscape, and infrastructure. Looking beyond the ‘problematization’ of the urban and the historic characterization of it as “crisis,” the following references revisit the transformation of different urban conditions as processes that are conditioned by pre-urban, pre-industrial and pre-Fordist factors. The second group, “Projections & Protoecologies,” is more projective and forward looking, with design methodologies and directive ecologies. This group explores new spatial models and media that provide ways of working and alternative applications related to contemporary practice. The sub-list of texts in each section are also organized in reverse chronology, starting with the most recent and contemporary reference, leading back through history of the early nineteenth century age of Western industrialization to trace critical lineages across different fields of knowledge as well as propose relevant associations and applications.

As references, these readings open a range of contemporary urban discourses that acknowledge critical, fin-de-siècle tendencies occurring worldwide: the emergence of ecology, the revival of geography, the overexertion of engineering, the spatial apartheid of infrastructure, and the inertia of urban planning vis-à-vis the pace of urban change today. Drawing from an array of urbanists, designers, ecologists, industrialists, engineers, and planners, these texts articulate canonical views from twentieth century America to give relevance to the processes and patterns of contemporary urbanization. Historically segregated by the professionalization of design disciplines, they provide a foundation for the re-engagement of an infrastructure discourse that synthesizes practices of planning, zoning, and engineering through the agency of design.

Preconditions & Processes

From Industrialization to Urbanization

Brenner, Neil & Christian Schmid. “Planetary Urbanisation” in Urban Constellations edited by Matthew Gandy (Berlin, DE: Jovis, 2012): 11–13.

Ouroussoff, Nicolai. “The Silent Radicals,” New York Times – Arts Section (July 20, 2007).

Waldheim, Charles. “Landscape as Urbanism,” in The Landscape Urbanism Reader (New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 2006): 35–54.

Welter, Volker M. “The Region-City: A Step toward Conurbations and the World City,” in Biopolis: Patrick Geddes and the City of Life (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002): 70–75.

Frampton, Kenneth. “Toward an Urban Landscape,” Columbia Documents of Architecture and Theory, Vol.4 (1995): 83–93.

Koolhaas, Rem. “Whatever Happened to Urbanism?” in S, M, L, XL (New York, NY: Monacelli Press, 1995): 958–971.

Hough, Michael. “The Urban Landscape: The Hidden Frontier,” Bulletin of the Association for Preservation Technology–Landscape Preservation, Vol.15 No.4 (1983): 9–14.

Reps, John William. “European Planning on the Eve of American Colonization” in Making of Urban America: a History of City Planning in the United States (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1965): 1–25.

Mumford, Lewis. “The Natural History of Urbanization” in Man’s Role in Changing the Face of the Earth, edited by William L. Jr. Thomas, (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1956): 382–398.

Giedion, Siegfried. Space, Time, and Architecture: The Growth of a New Tradition (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1941).

Wirth, Louis. “Urbanism as a Way of Life” in American Journal of Sociology Vol.44 No.1 (July 1938): 1–2.

Geddes, Patrick. “The Evolution of Cities,” in Cities in Evolution: An Introduction to the Town Planning Movement and to the Study of Civics (London, UK: Williams and Norgate, 1915): 1–24.

Olmsted, Frederick Law. “Expanding Cities: Random Versus Organized Growth (1868)” in Civilizing American Cities: Writings on City Landscapes ed. S.B. Sutton (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1971): 21–99.

*Scruton, Paul. “The New Urban World” (graphic), The Guardian (Saturday, June 27, 2007).

Infrastructure, & the Ascent of Civil Engineering

Bélanger, Pierre. “Redefining Infrastructure” in Ecological Urbanism, ed. Mohsen Mostafavi and Gareth Doherty (Baden, CH: Lars Müller Publishers, 2010): 332–349.

Meyboom, AnnaLisa. “Infrastructure as Practice,” Journal for Architectural Education Vol.62 No.4 (2009 May): 72–81.

Petroski, Henry. “Things Small and Large” in Success through Failure: the Paradox of Design (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006): 97–115.

Jones, Peter. “Cultivating the Art of the Impossible” in Ove Arup: Master Builder of the Twentieth Century (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006): 282–301.

Picon, Antoine. “Engineers and Engineering History: Problems and Perspectives,” History and Technology Vol. 20 No.4, (December 2004): 421–436.

Edwards, Paul N. “Infrastructure & Modernity: Force, Time and Social Organization in the History of Sociotechnical Systems” in Modernity and Technology edited by Thomas J. Misa, Philip Brey and Andrew Feenberg (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003): 185–226.

Williams, Rosalind. Retooling: A Historian Confronts Technological Change (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2002).

Grigg, Neil S. et al. “Civil Engineering: History, Heritage, and Future” in Civil Engineering Practice in the Twenty-First Century: Knowledge and Skills for Design and Management (Reston VA: ASCE Press, 2001): 13–44.

Koolhaas, Rem. “Bigness or the Problem of Large” in S,M,L,XL (New York, NY: Monacelli Press, 1995): 494–517.

Schodek, Daniel L. Landmarks in Civil Engineering (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1987).

Layton, Edwin. The Revolt of Engineers: Social Responsibility and the American Engineering Profession (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986).

Choate, Pat and Susan Walter. “Declining Facilities/Declining Investments” in America in Ruins: The Decaying Infrastructure (Durham, NC: Duke Press Paperbacks, 1983): 1–29.

de Camp, L. Sprague. The Ancient Engineers (New York, NY: Ballantine Books, 1960).

Ley, Willy. Engineer’s Dreams (New York, NY: The Viking Press, 1954).

Beers, Henry P. “A History of the U.S. Topographical Engineers, 1813–1863,” Military Engineering 34 (June, 1942): 287–291 and (July, 1942): 348–352.

*Thom, W. Taylor. “Science and Engineering and the Future of Man” in Science and the Future of Mankind (World Academy of Art & Science – Series 1) edited by Hugo Boyko (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1961): 256.

Whatever Happened to Planning? Zoning, after Euclid

Wolf, Michael A. “On the Road to Zoning” in The Zoning of America: Euclid vs. Ambler (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2008): 17–31.

Light, Jennifer S. “Introduction” and “Planning for the Atomic Age” in From Warfare and Welfare: Defense Intellectuals and Urban Problems in Cold War America (Baltimore, MD: The John Hopkins University Press, 2003): 1–31.

Davidson, Joel. “Building for War, Preparing for Peace: World War II and the Military-Industrial Complex” in World War II and the American Dream: How Wartime Building Changed a Nation edited by Donald Albrecht (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995): 184–229.

Nelson, Robert H. “Zoning Myth and Practice – from Euclid into the Future” in Zoning and the American Dream edited by Jerold Kayden and Charles M. Haar (Chicago, IL.: Planners Press, 1989): 299–318.

Boyer, M. Christine. “The Rise of the Planning Mentality” in Dreaming the Rational City: The Myth of American City Planning (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1983): 59–82.

Galbraith, John Kenneth. “The Planning System” in Economics and the Public Purpose (New York, NY: Penguin Books, 1973): 96–190.

Wilhem, Sidney W. “Introduction” in Urban Zoning and Land Use Theory (New York, NY: Free Press of Glencoe, 1962): 1–11.

Wiener, Norbert. “How US Cities Can Prepare for Atomic War,” Time Magazine Life Publications (Dec. 18 1950): 77–86.

Hilberseimer, Ludwig. “Cities and Defense (c.1945)” in In the Shadow of Mies: Ludwig Hilberseimer: Architect, Educator and Urban Planner by Richard Pommer, David Spaeth, and Kevin Harrington with selected writings by Ludwig Hil-berseimer (Chicago, IL: Art Institute of Chicago & Rizzoli International, 1988): 89–93.

*Choay, Françoise. “The Modern City: Planning in the 19th Century” in Planning and Cities edited by George R. Collins (London: Studio Vista, 1969): 121–125.

Sub-Urbanization & Super-Urbanization

Segal, Rafi. “Urbanism Without Density” in Architectural Design AD Vol. 78 No.1 (Jan.–Feb. 2008): 6–11.

Simone, AbdouMaliq. “At the Frontier of the Urban Periphery” in Sarai Reader 2007: Frontiers edited by Monica Narula, Shuddhabrata Sengupta, Jeebesh Bagchi, and Ravi Sundaram (Delhi, IN: Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, 2007): 462–470.

Davis, Mike. “The Urban Climateric” and “the Prevalence of Slums” in Planet of Slums (New York, NY: Verso, 2006): 1–19, 20–50.

Bruegmann, Robert. “Defining Sprawl” and “Early Sprawl” in Sprawl: A Compact History (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2005): 17–20, 21–32.

Sieverts, Thomas. “The Living Space of the Majority of Mankind: an Anonymous Space with no Visual Quality” in Cities without Cities (London, UK: Spon Press, 2003): 1–47.

Lerup, Lars. “Stim and Dross: Rethinking the Metropolis” in After the City (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000): 46–63.

Harvey, David. “Flexible Accumulation through Urbanization, Reflections on Post-Modernism in the American City” in Post-Fordism: A Reader edited by Ash Amin (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1994): 361–386.

Gottman, Jean. “The Main Street of the Nation” and “The Dynamics of Urbanization” in Megalopolis (New York, NY: Twentieth Century Fund, 1961): 3–22.

Wright, Frank Lloyd. “Decentralization” in The Living City (New York, NY: Horizon Press, 1958): 77–105.

Gruen, Victor. “Dynamic Planning for Retail Areas,” Harvard Business Review (Nov.–Dec. 1954): 53–62.

*Thomas, Gary Scott. “Micropolitan America” (map) American Demographics 20 (1 May 1989): 1–2, and U.S. Department Of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration, Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas of the United States and Puerto Rico (Washington DC: US CENSUS Bureau Geography Division, December, 2006).

Ecological Emergence & Urban Complexity

Reed, Chris. “The Agency of Ecology” in Ecological Urbanism edited by Mohsen Mostafavi and Gareth Doherty (Baden, Switzerland: Lars Müller Publishers, 2010): 324–329.

Del Tredici, Peter. “Brave New Ecology,” Landscape Architecture 96 (February, 2006): 46–52.

Kangas, Patrick. “Designing New Ecosystems” and “Principles of Ecological Engineering” in Ecological Engineering: Principles and Practice (Boca Raton, FA: CRC Press, 2004): 13–24.

Nordhaus, Ted and Michael Shellenberger. “The Death of Environmentalism: Global Warming Politics in a Post-Environmental World,” The Break Through Institute, http://the-breakthrough.org/PDF/Death_of_Environmentalism.pdf.

Mol, Arthur P.J. “The Environmental Transformation of the Modern Order” in Modernity and Technology edited by Thomas J. Misa, Philip Brey, and Andrew Feenberg (Cambridge, MIT Press, 2003): 303–325.

Forman, Richard T.T. “The Emergence of Landscape Ecology” in Landscape Ecology edited by Richard T.T. Forman and Michel Godron (New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, 1986): 3–31.

Odum, Howard T. “Cities and Regions” in Ecological and General Systems: An Introduction to Systems Ecology (New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, 1983): 532–553.

McHale, John. “Dimensions of Change,” and “An Ecological Overview,” in The Future of the Future (New York, NY: Braziller, 1969): 57–74.

McHarg, Ian. “An Ecological Method for Landscape Architecture,” Landscape Architecture 57 (January 1967): 105–107.

Sears, Paul B. “Ecology – A Subversive Subject,” Bioscience Vol.14 No.7 (1964): 11–13.

*Djalali, Amir with Piet Vollaard. “The Complex History of Sustainability: An Index of Trends, Authors, Projects and Fiction,” Volume #18 – After Zero (2008): 33–41.

Projections & Protoecologies

Constructed Ecologies & Soft Systems

Bélanger, Pierre. “Landscape as Infrastructure,” Landscape Journal 28 (Spring 2009): 79–95.

Allen, Stan. “Infrastructural Urbanism” in Points + Lines: Diagrams for the City (New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999): 46–89.

Corner, James. “Eidetic Operations & New Landscapes” in Recovering Landscape: Essays in Contemporary Landscape Architecture, edited by James Corner (New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999): 153–170.

Frampton, Kenneth. “Megaform as Urban Landscape,” 1999 Raoul Wallenberg Lecture (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1999): 1–42.

Corner, James. “Measures of Land” and “Measures of Control” in Taking Measures Across the American Landscape (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996): 41–96.

Easterling, Keller. “Network Ecology,” Landscapes – Felix Journal of Media Arts & Communication 2 No.1 (1995): 258–265.

Banham, Reyner. “Antecedents, Analogies, and Mégastructures trouvées” in Megastructures: Urban Futures of the Recent Past (London, UK: Thames and Hudson, 1976): 13–32.

Jackson, John Brinkerhoff. “The Public Landscape (1966)” in Landscapes: Selected Writings by J.B. Jackson edited by Ervin H. Zube (Amherst, MA: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1970): 153–160.

Lynch, Kevin. “Earthwork & Utilities” in Site Planning (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1962): 157–188.

Ely, Richard T. and George S. Wehrwein. Land Economics (New York, NY: The MacMillan Company, 1940): 1–23, 50–73.

Mumford, Lewis. “The Renewal of the Landscape” in The Brown Decades: A Study of the Arts of America, 1865–1895 (New York, NY: Dover Publications, 1931): 75–106.

*Bélanger, Pierre. “Venice Lagoon 2100: A Strategy for the economy and ecology of the Venice Lagoon” in Concurso 2G Competition: Venice Lagoon Park edited by Mónica Gili (Barcelona, Spain: 2G International Review, 2008): 52–53.

*Odum, Howard T. “Representative City System” in Ecological and General Systems (New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, 1983): 548.

Water: Public Works, Hydrologic Systems, & Coastal Dynamics

Mathur, Anuradha and Dilip Da Cunha. “Monsoon in an Estuary” and “Estuary in a Monsoon” in SOAK: Mumbai in an Estuary (New Delhi, India: Rupa and Co., 2009), 3–9, 185–187.

De Meulder Brian, and Kelly Shannon. “Water and the City: the ‘Great Stink’ and Clean Urbanism” in Water Urbanisms edited by De Meulder, V. d’Auria, J. Gosseye and K. Shannon (Amsterdam, NL: SUN, 2008): 5–9.

Barles, Sabine. “The Nitrogen Question,” Journal of Urban History 33 (2007): 794–812.

Picon, Antoine. “Constructing Landscape by Engineering Water” in Landscape Architecture in Mutation: Essays on Urban Landscapes by Institute for Landscape Architecture, ETH Zurich (Zurich, CH: gta Verlag, 2005), 99–114.

Schlesinger, Arthur M. Jr., “The Battle for Public Development and Remaking the Tennessee Valley” in The Coming of the New Deal, 1933–1935 (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 2003): 319–334.

Wolff, Jane. “A Brief History of the Delta” in Delta Primer: A Field Guide to the California Delta (San Francisco, CA: William Stout Publishers, 2003): 37–45.

Gandy, Matthew. “Water, Space, and Power” in Concrete and Clay: Reworking Nature in New York City (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002): 19–75.

Melosi, Martin. “Pure and Plentiful: from Protosystems to Modern Water Works,” “Subterranean Networks: Waste-water Systems as Works in Progress” in The Sanitary City: Urban Infrastructure in America from Colonial Times to the Present (Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press, 2000): 50–68.

Rogers, Peter. “Water Resources and Public Policy” in America’s Water: Federal Roles and Responsibilities (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993): 1–24.

Illich, Ivan. “The Dirt of Cities” in H20 & The Waters of For-getfulness (London, UK: Maryon Boyars Publishers, 1986): 45–76.

Leuba, Clarence. “The Tennessee Valley Authority: Accomplishments & Disappointments” in A Road to Creativity: Arthur Morgan – Engineer, Educator, Administrator (North Quincy, MA: The Christopher Publishing House, 1971): 163–202.

Wolman, Abel. “The Metabolism of Cities,” Scientific American Vol. 213 No.3 (1965): 178–193.

*Bélanger, Pierre. “Risk Landscape: Coastal Flood Zones, Land Reclamation & Hypotrophic Zones of the World” (graphic) in Maasvlakte 2100 by OPSYS (Rotterdam, Netherlands: Rotterdam Port Authority, 2010): 171–172.

Waste: Landscape of Surplus, Cycling & Accumulation

Bélanger, Pierre. “Airspace: The Ecologies and Economies of Landfilling in Michigan and Ontario” in Trash edited by John Knechtel (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006): 132–155.

Berger, Alan. “The Production of Waste Landscape” and “Post-Fordism: Waste Landscape through Accumulation” in Drosscape: Wasting Land in Urban America (New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 2006): 46–52, 53–75.

Engler, Mira. “Contemplating Waste: Theories and Constructs” in Designing America’s Waste Landscapes (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004): 1–41.

Berger, Alan. “The Altered Western Landscape” in Reclaiming the American West (New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 2002): 15–55.

Bélanger, Pierre. “Jankara Jetty: Recycling Cloverleaf,” and “Ebute Ero: Market Economies” in Harvard Project on the City: Lagos edited by Rem Koolhaas and Jeffrey Inaba (Cambridge, MA: Graduate School of Design, 2000).

Kirkwood, Niall. “Manufactured Sites: Integrating Technology and Design in Reclaimed Landscapes” in Manufactured Sites: Re-Thinking the Post-Industrial Landscape edited by Niall Kirkwood (London, UK: SPON Press, 2001): 3–11.

Miller, Benjamin. “Prologue: Garbage” in Fat of the Land: Garbage in New York – The Last Two Hundred Years (New York, NY: Four Walls Eight Windows, 2000): 1–16.

Hawken, Paul. “The Creation of Waste” in The Ecology of Commerce: A Declaration of Sustainability (New York, NY: Harper Collins, 1993): 37–55.

Frosch, Robert A. and Nicholas E. Gallopoulos. “Strategies for Manufacturing,” Scientific American – Special Issue: Managing Planet Earth (1989): 94–102.

Ford, Henry. “Learning from Waste” in Today and Tomorrow (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page, 1926): 89–98.

*Bélanger, Pierre. “Shit City: Aggregate landscape of waste flows, exchanges and synergies accumulated during the past five centuries in the Port of Rotterdam” (graphic) in Maasvlakte 2100 by OPSYS (Rotterdam, Netherlands: Rotterdam Port Authority, 2010): 60–61.

Food: Agrarian Landscapes, Market Economies, & Harvest Regions

Imbert, Dorothée. “Let Them Eat Kale,” Architecture Boston (Fall 2010): 24–26.

Rice, Andrew. “Agro-Imperialism?,” NY Times Magazine (Nov. 2, 2009): 46–51.

Bélanger, Pierre and Angela Iarocci. “Foodshed: The Global Infrastructure of the Ontario Food Terminal” in TRASH edited by John Knechtel (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007): 116–138.

Pollan, Michael. “The Farm” in The Omnivore’s Dilemma: a Natural History of Four Meals (New York, NY: Penguin Press, 2006): 32–56.

Branzi, Andrea. “Agronica” in Weak & Diffuse Modernity: The World of Projects at the Beginning of the 21st century (Milan, IT: Skira, 2006): 132–146.

Mazoyer, Marcel and Laurence Roudart. “Humanity’s Agrarian Heritage” in A History of World Agriculture: From the Neolithic Age to the Current Crisis, trans. James H. Membrez (New York, NY: Monthly Review Press, 2006): 9–26.

Diamond, Jared. “From Food to Guns, Germs and Steel: The Evolution of Technology” in Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies (New York, NY: Norton & Company, 1999): 239–264.

Hough, Michael. “City Farming” in Cities & Natural Process: A Basis for Sustainability (London, UK: Routledge, 1995): 160–188.

Giedion, Siegfried. “Mechanization and the Soil: Agriculture” in Mechanization Takes Command: A Contribution to an Anonymous History (New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 1969): 130–147.

Hedden, Walter P. “The Food Supply of a Great City” in How Great Cities are Fed (New York, NY: D.C. Heath, 1929): 1–16.

Piotr Kropotkin, “The Possibilities of Agriculture” (Chapters 3–4) in Fields, Factories And Workshops: or Industry Combined with Agriculture and Brain Work with Manual Work (London, UK: Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1912): 79–187.

*Brandford, Sue. “Global Land Grab” (graphic), The Guardian (22 November 2008).

*Bélanger, Pierre. Global Foodshed & PLU Landscape (graphic) (Toronto, ON: Ontario Food Terminal Board, 2007).

Fuel: Energy Networks & the Carbon Landscape

Ghosn, Rania. “Energy as Spatial Project” in Landscapes of Energy – New Geographies Journal 02 (2009): 7–10.

Friedmann, S. Julio and Thomas Homer-Dixon. “Out of the Energy Box,” Foreign Affairs, Volume 83 No.6 (November/December 2004): 72–83.

Ascher, Kate. “Power” in The Works: Anatomy of a City (New York, NY: Penguin Press, 2005): 94–121.

Jakob, Michael. “Conversation with Paul Virilio,” and “Architecture and Energy or the History of an Invisible Presence” in 2G International Architecture Review No. 18 (2001): 4–32.

Brennan, Teresa. “Energetics” in Exhausting Modernity: Grounds for a New Economy (New York, NY: Routledge, 2000): 41–54.

Ausubel, Jesse H. “The Liberation of the Environment: Technological Development and Global Environmental Change,” Daedalus Vol. 125 No. 3 (Summer 1996): 1–17.

Dozier, Jeff and William Marsh. “Energy Processes on the Earth’s Surface” in Landscape: An Introduction to Physical Geography (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing, 1981): 1–20.

llich, Ivan. Energy and Equity (London, UK: Calder and Boyars, 1974): 1–29.

Odum, Howard T. “Energy, Ecology, Economics,” Ambio Vol. 2 No.6 Energy in Society: A Special Issue (1973): 220–227.

Mumford, Lewis. “Power & Mobility” in Technics and Civilization (New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1934): 235–239.

*Bélanger, Pierre. “Power Perestroika” in New Geographies 02 – Landscapes of Energy edited by Rania Ghosn (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press): 119–124.

Logistics: Industrialization, Decentralization & Disassembly

Waldheim, Charles and Alan Berger. “Logistics Landscape” in Landscape Journal Vol.27 No.2 (2008): 219–246.

Bélanger, Pierre. “Landscapes of Disassembly” in Topos 60 (October, 2007): 83–91.

Schumacher, Patrik and Christian Rogner. “After Ford” in Stalking Detroit edited by Georgia Daskalakis, Charles Waldheim and Jason Young (ACTAR, Barcelona, 2001): 48–56.

Nash, Gary B. “The Social Evolution of Pre-Industrial American Cities, 1700–1820” in The Making of Urban America, edited by Raymond A. Mohl (Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources, 1997): 15–36.

Dandaneau, Steven P. “Introduction: Ideology and Dependent Deindustrialization” in A Town Abandoned: Flint, Michigan Confronts Deindustrialization (Albany State University of New York Press, 1994): xix–xxviii.

Garreau, Joel. “The Foundry” in The Nine Nations of North America (New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1981): 48–97.

Conway, McKinley. “Emergence of the Park Concept and Proliferation of Units” and “Types of Parks” in Industrial Park Growth: an Environmental Success Story (Atlanta: Con-way Publications, 1979): 5–20, 45–62.

Galbraith, John Kenneth. “The Nature of Industrial Planning” in The New Industrial State (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1967): 25–41.

Reps, John William. “The Towns that Companies Built” in Making of Urban America: a History of City Planning in the United States (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1965): 414–448.

Mumford, Lewis. “Paleotechnic Paradise: Coketown” in The City in History (New York, NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1961): 446–481.

*Bélanger, Pierre. “Kalundborg’s Protoecology & Wasteshed” (graphic) in Topos 60 (October, 2007): 88, and Fuller, Buckminster. Acceleration in the Discoveries of Science: Profile of the Industrial Revolution (1946, 1964).

Mobility I: Speed, Transportation & Surface Networks

Guldi, Jo. “Road to Rule” in Roads to Power: Britain Invents the Infrastructure State (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012): 1–24.

Bélanger, Pierre. “Synthetic Surfaces” in The Landscape Urbanism Reader edited by Charles Waldheim (New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 2006): 239–265.

Schnapp, Jeffrey T. “Three Pieces of Asphalt” in Grey Room 11 (Spring, 2003): 5–21.

McPhee, John. “Fleet of One: Eighty Thousand Pounds of Dangerous Goods” in The New Yorker – Annals of Transport Section, (February 17–24, 2003): 148–162.

Gregotti, Vittorio. “The Road: Layout and Built Object” in Casabella No. 553–554 (January–February 1989): 2–5, 118.

Virilio, Paul. “The Dromocratic Revolution” in Speed & Politics: An Essay on Dromology, translated by Mark Polizzotti (New York, NY: Autonomedia Press, 1986): 1–34.

Mumford, Lewis. “Landscape and Townscape,” and “The Highway and the City” in The Highway and the City (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1981): 233–256.

Frampton, Kenneth. “The Generic Street as a Continuous Built Form” in On Streets edited by Stanford Anderson (Cambridge: The Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, MIT Press, 1978): 308–336.

Newton, Norman T. “Parkways and Their Offpsring” in Design on the Land: The Development of Landscape Architecture (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1971): 596–619.

Ritter, Paul. “History of Traffic Segregation” in Planning for Man and Motor (Oxford, UK: Pergamon Press, 1964): 314–330.

Jellicoe, Sir Geoffrey “Segregation of Traffic” in Motopia: Evolution of the Urban Landscape (New York, NY: Praeger, 1961): 117–140.

Olmsted, Frederick Law. “History of Streets” (Washington, DC: Frederick Law Olmsted Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, 1888).

*Staley, E. “Technical Progress in Travel Time” (graphic) in World Economy in Transition (New York, NY: Council on Foreign Relations, 1939): 6.

Mobility II: Communications, Broadband, & Subterranean Urbanism

NY Times, “A Plan for Broadband,” New York Times OP-ED Section (Sunday, March 21, 2010): 1.

Wu, Tim. “Bandwidth Is the New Black Gold,” Time Magazine (Thursday, Mar. 11, 2010)

Schnapp, Jeffrey T. “Fast (Slow) Modern” in Speed Limits (Montreal, QC: CCA, 2009): 26–37.

Varnelis, Kazys. “Invisible City: Telecommunications” in The Infrastructural City: Networked Ecologies in Los Angeles (Barcelona, ES: ACTAR, 2008): 118–129.

Bélanger, Pierre. “Underground Landscape: The Urbanism & Infrastructure of Toronto’s Downtown Pedestrian Network,” Journal of Underground Space and Tunnelling Vol. 22 No.3 (2006 October): 272–292.

Alonzo, Eric. “De la place-carrefour à l’échangeur, instrumentalisation du système giratoire” and “Le réseau des giratoires, vers une nouvelle organisation des territoires urbains”, in Du Rond-Point au Giratoire (Paris, FR: Parenthèses, 2005): 84–100, 127–133.

Wall, Alex. “Programming the Urban Surface” in Recovering Landscape: Essays in Contemporary Landscape Architecture edited by James Corner (New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999): 233–250.

Schmandt, Jurgen, Frederick Williams, Robert H. Wilson, and Sharon Strover, editors. “Introduction” in The New Urban Infrastructure: Cities and Telecommunications (New York, NY: Praeger, 1990): 1–6.

McCluskey, Jim. “Networks” in Road Form and Townscape (London: Architectural Press, 1979): 12–38.

Giedion, Siegfried. “Movement” in Mechanization Takes Command: A Contribution to an Anonymous History (New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 1969): 14–44.

*McHale, John. “Vertical Mobility” (graphic) in The Future of the Future (New York, NY: Braziller, 1969): 69.

From Globalization to Regionalization

Bélanger, Pierre. “Regionalisation,” JoLA – The Journal of Landscape Architecture (Fall 2010): 6–23.

Forman, Richard T. T. “Urban Region Planning” in Urban Regions: Ecology and Planning Beyond the City (Oxford: Cambridge University Press, 2008): 45–50.

Wolff, Jane. “Redefining Landscape” in The Tennessee Valley Authority: Design and Persuasion edited by Tim Culvahouse (New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 2007): 52–63.

Easterling, Keller. “Partition: Watershed & Wayside” in Organization Space: Landscapes, Houses and Highways in America (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999): 54–66.

Branzi, Andrea. “The Hybrid Metropolis” in Learning from Milan: Design and the Second Modernity (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1988): 20–24.

Gregotti, Vittorio. “La Forme du Territoire (The Shape of Landscape),” AA L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui No.218 (December 1981): 10–15.

Dal Co, Francesco. “From Parks to the Region: Progressive Ideology and the Reform of the American City” in The American City: From the Civil War and the New Deal ed. Giorgio Cucci, Francesco Dal Co, Mario Manieri-Elia, and Manfredo Tafuri (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1979): 143–292.

McHarg, Ian. “The City: Process & Form” in Design with Nature (Garden City, NY: Natural History Press, 1969): 175–186.

Odum, Howard W. and Harry Estill Moore. “The Rise and Incidence of American Regionalism” in American Regionalism: A Cultural-Historical Approach to National Integration (New York, NY: Henry Holt & Company, 1938): 3–34.

MacKaye, Benton. “Appalachian America – A World Empire” in The New Exploration: A Philosophy of Regional Planning (New York, NY: Harcourt, 1928): 95–119.

Landscape Cartography & the Agency of Mapping

Rosenberg, Daniel & Anthony Grafton. Cartographies of Time (New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 2010).

Dodge, Martin, Perkins, Chris, and Kitchin, Rob. “Mapping Modes, Methods and Moments: A Manifesto for Map Studies” in Rethinking Maps: New Frontiers in Cartographic Theory (New York, NY: Routledge, 2009): 220–243.

Schäfer, Wolf. “Ptolemy’s Revenge: A Critique of Historical Cartography” in Coordinates Series A-3 (August 29, 2005): 1–16.

Archibald, Sasha, and Rosenberg, Daniel. “A Timeline of Timelines,” Cabinet 13 – Futures (Spring 2004).

Cosgrove, D. “Mapping Meaning” in Mappings (London: Reaktion, 1999): 1–23.

Kwinter, Sanford. “The Genealogy of Models,” Any 23: Diagram Work (Fall 1998): 59.

Corner, James. “Aerial Representation & The Making of Landscape” in Taking Measure across the American Landscape by James Corner & Alex S. Mclean (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996): 15–20.

O’Hara, Robert J. “Representations of the Natural System in the Nineteenth Century” in Biology and Philosophy 6 (1991): 255–274.

Monmonier, Mark S. “Introduction” in How to Lie with Maps (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1991): 1–4.

Harley, J.B. “Deconstructing the Map,” Cartographica 26: 2 (1989): 1–20.

Harley, J.B. “Maps, Knowledge, and Power” in The Iconography of the Landscape edited by D. Cosgrove and S. Daniels (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 1988): 277–312.

Wood, Denis. and Fels, John. “Designs on Signs / Myth and Meaning in Maps” in Cartographica Vol.23 No.3 (1986): 54–103.

Fisher, Howard T. Mapping Information: The Graphic Display of Quantitative Information (Cambridge, MA: Abt Books, 1982).

Bertin, Jacques. Sémiologie Graphique: Les Diagrammes, les Réseaux, les Cartes (Paris, FR: Gauthier-Villars, 1967).

Bunge, William. Theoretical Geography (Lund, SW: Gleerup, 1962).

Urban Hazards: Risk, Contingency & Indeterminate Landscapes

Meyer, Elizabeth K. “Slow Landscapes” in Harvard Design Magazine Vol. 31 (Fall/Winter 2010): 22–31.

Lister, Nina-Marie. “Bridging Science and Values: The Challenge of Biodiversity Preservation” in The Ecosystem Approach edited by James J. Kay, Nina-Marie E. Lister, and David Waltner-Toews (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2008): 83–108.

Berrizbeitia, Anita. “Re-Placing Process” in Large Parks edited by Julia Czerniak and George Hargreaves (New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 2007): 175–198.

Klemeš, Vit. “Risk Analysis: The Unbearable Cleverness of Bluffing” in Risk, Reliability, Uncertainty, and Robustness of Water Resource Systems edited by János Bogárdi and Zbigniew Kundzewicz (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002): 22–29.

Mathur, Anuradha and Dilip DaCunha. “Introduction: Mississippi Horizons” in Mississippi Floods: Designing a Shifting Landscape (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001): 1–31.

Latz, Peter. “The Idea of Making Time Visible,” Topos Vol. 33 (2000): 94–99.

Beck, Ulrich. “Environment, Knowledge, and Indeterminacy: Beyond Modernist Ecology?” in Risk, Environment & Modernity edited by Scott Lash, Bronislaw Szerszynski, and Brian Wynne (London, Sage Publications, 1996): 27–43.

Forman, Richard T.T. “Landscape Change” in Landscape Ecology by Richard T.T. Forman and Michel Godron (New York, NY: Wiley, 1986): 427–458.

Perrow, Charles. “Living with High-Risk Technologies” in Normal Accidents: Living with High-Risk Technologies (New York, NY: Basic Books, 1984): 305–352.

* indicates additional graphic media and representational references (maps, diagrams, charts) added at the end of each reading section.

> Landscape Revolutions

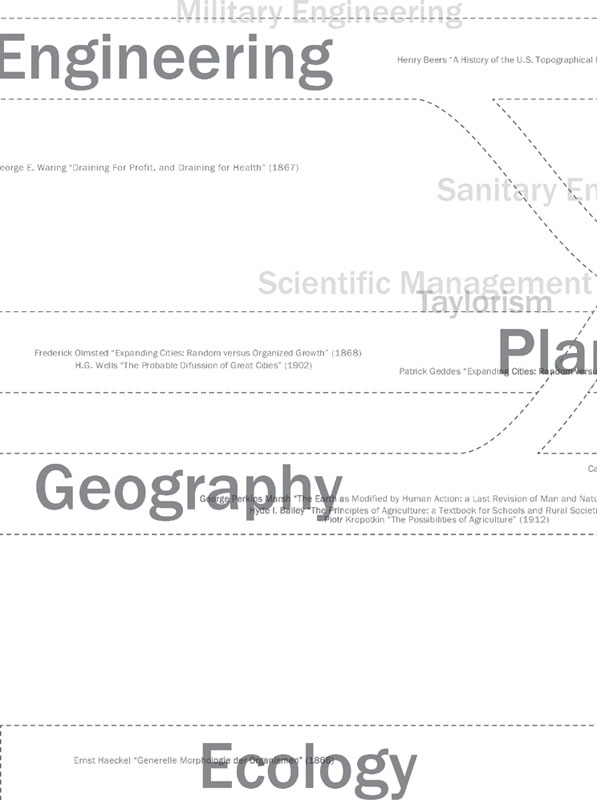

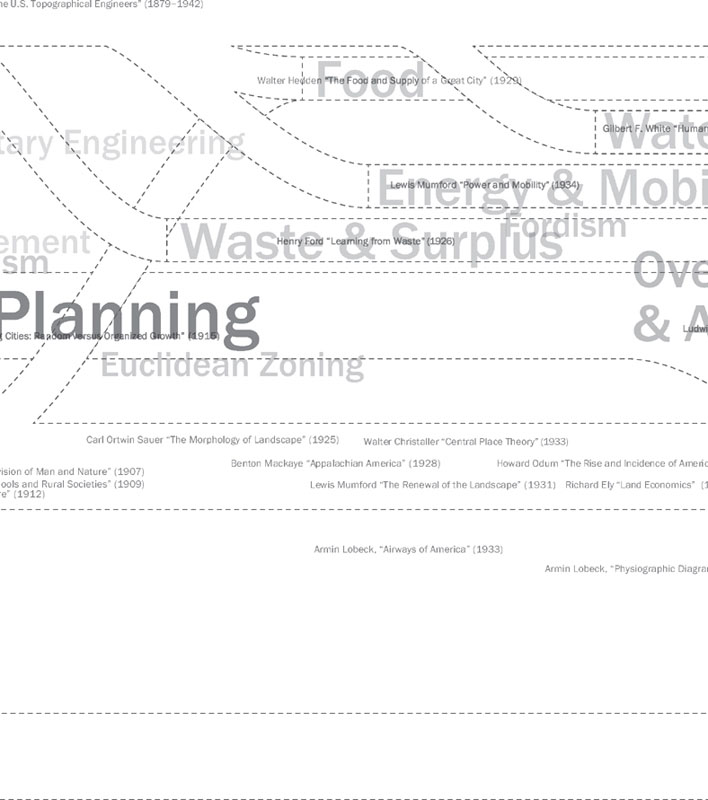

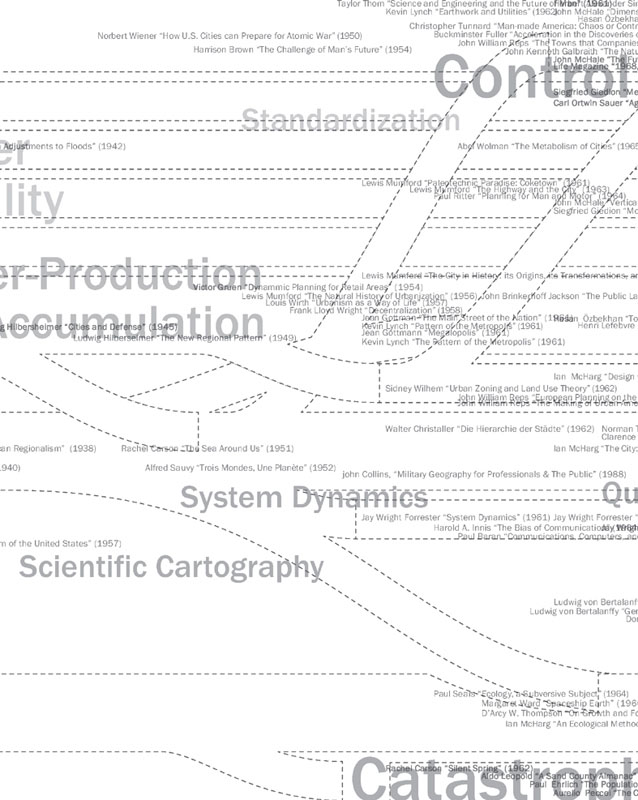

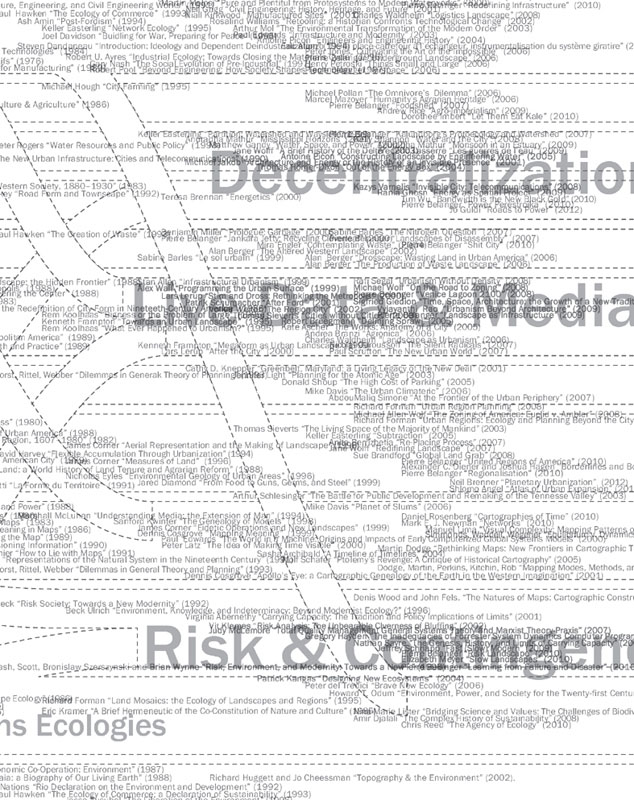

Using the format of a timeline, the following bibliographical references outline the intersection and convergence of several fields of knowledge in engineering, ecology, planning and geography. Across time, the diagram proposes the emergence of landscape as an overlapping field of design practice and theoretical investigation that has been under development during the past two centuries, and now beginning to blossom as an area of inquiry, engagement, and intervention. Diagram: OPSYS/Daniel Daou

Urbanism, without Infrastructure?

Bibliographic note and future readings exploring practices beyond the disciplines of engineering, architecture, and planning

If infrastructure has become the interface through which we understand urban life, then it also provides an index to interpret social and ecologic change. Whether we speak about roads and their relationship to the transformation of watersheds, about power supply systems and the sources of energy, about patterns of consumption and the generation of waste streams, or about patterns of development along coastal zones and the influence of rising tides or increasing storms, the large scale technological systems of roads, wires, pipes, and plants that support urban economies are unequivocally tied to the landscape of ecological externalities and social-political dynamics that underlie them. Yet, due to their scale, magnitude, and ubiquity, these associations and dualities are seldom revealed or visible in the engineering of infrastructural systems. Instead, and very often, they are excluded, homogenized, neutralized, or attenuated. In short, the industrial metropolis of the nineteenth century could not have existed without the fixed, centralized, technocratic, underground infrastructure that lies below cities.

So what happens to urban patterns and market economies when these socio-ecologic complexities change or when new vulnerabilities emerge? What happens when climatic zones shift or populations migrate? What happens to the development policies, the engineering systems, or zoning mechanisms that we have planned for in relationship to specific plans, properties, parameters, and policies based on the exactitude of growth projections and demographics?

By redefining the landscape of infrastructure as both ecological media and measure, these questions explore the omnipresence of flexible patterns of occupation and responsive market configurations in the absence of conventional, centralized infrastructure. Looking outside the temperate, industrial worldview that underpins Western civilizations, a profile of contemporary urban patterns in emerging economies will serve to postulate the potential persistence of urbanization beyond the parameters and problématiques of population growth; further putting into question the systematization of infrastructure planning and technocratic frameworks that are required to finance and service them. By revealing more flexible and more dynamic distributions of urban territories, we can put into question the exclusive reliance on growth to produce urbanism and decouple the notions of permanence and durability from sustainability, toward understanding how patterns and fields of urbanization can strategically exist without conventional infrastructure and how we can address emerging ecological indeterminacies through weaker forms of planning, with more contingent, reflexive methods of design and un-design.

Focusing on the entanglement of state, infrastructure, and development, the following key references provide an introduction to the study and research of infrastructural ecologies. Chronicling the underlying nature of infrastructure as invisible instrument of state power, these texts proposes how central forces of growth and projects of development often instrumentalize that power to varying degrees of legibility. The landscape of ecological processes that underlie these transformations thus provide both a re-reading of territorial powers and in some instances, resistance to counter prevailing powers. Together, they propose new visions of state and citizenship through weaker forms of engineering (and planning), and softer forms of infrastructure. In this light, landscape provides both a model of thought and medium of intervention where the existing body politic can thus be transformed by an emerging body ecologic.

Jo Guldi, Roads to Power: Britain Invents the Infrastructure State (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012).

Stuart Elden, “Land, Terrain, Territory,” Progress in Human Geography Vol.34 No.6 (April 21, 2010): 799–817.

Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, Friction: An Ehtnography of Global Connection (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005).

Richard Peet and Michael Watts, Liberation Ecologies: Environment, Development, Social Developments (London, Routledge, 1996).

Rosalind Williams, “Cultural Origins and Environmental Implications of Large Technological Systems,” Science in Context 6 (1993): 377–403.

William Marsh, Jeff Dozier, Landscape: An Introduction to Physical Geography (New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, 1981).

André Gorz, Ecology as Politics (Écologie et Politique) translated by Patsy Vigderman and Jonathan Cloud (London, UK: Pluton Press, 1987/1975).

François Fourquet, Lion Murard, Les Équipements du Pouvoir; Villes, Territoires et Équipements Collectifs–Recherches No. 13 (Fontenay-sous-Bois, FR: Union Générale d’Éditions, 1973).

Howard T. Odum, Environment, Power, and Society (New York, NY: Wiley-Interscience, 1971).

John Kenneth Galbraith, The New Industrial State (New York, NY: Signet, 1967).

Christopher Tunnard & Boris Pushkarev, Man-Made America: Chaos or Control (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1963).

Carl O. Sauer, Agricultural Origins & Dispersals (New York, NY: The American Geographical Society, 1952).

To the new class of technical experts—the technocrats—that the economist John Kenneth Galbraith warned of in The New Industrial State (1967), Donald Worster adds in his chapter “The Flow of Power in History” cited here from his Rivers of Empire: Water, Aridity, and the Growth of the American West (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1985) that,

“the best exemplar of that power of expertise” is “the contemporary engineer […] Though not himself necessarily concerned with profit making [and capitalism], he reinforces directly and indirectly the rule of instrumentalism and unending economic growth. The engineer is not interested in understanding things for their own sake or for the sake of insight, but in accordance with their [sic] being fitted into a scheme, no matter how alien to their own inner structure; this holds for living beings as well as inanimate things. The engineer’s mind is that of industrialism in its streamlined form. His purposeful rule would make men an agglomeration of instruments without a purpose of their own. Democracy cannot survive where technical expertise, accumulated capital, or their combination is allowed to take command.” (57)

Together, Galbraith’s prediction of technocratic and corporate growth, with Worster’s precaution against the dominion of technocrats, propose an alternative epistemological direction: a second conclusion. If we are to consider the era of urbanism (and processes of urbanization it implies) as an advancement beyond the age of industrialism, then the current domination by the industrial state and continued rise of the corporation propose an alternative reality. Notwithstanding the perpetual technological obsolescence that the “expansive disintegration” of engineering requires to rule over daily life, the current hegemony of technocratic and bureaucratic engineering as Rosalind Williams has observed in her Retooling: A Historian Confronts Technological Change (2002) seems to be tracing the contours of a super-industrial age; one of a magnitude so large and so encompassing that its influence is no longer visible, and barely perceptible, nor detectable.

From this alternative vantage then, if we are to advance beyond the centralization of capital in trade, or beyond the concentration of currency in exchange, that underlie today’s economies, perhaps we must reconsider whether in fact, we have ever been urban at all?

Perhaps, where development from the Western industrial world has not yet fully formed or transformed by engineering, where the technocrats do not reign, or where resistance to colonialism is growing, there may be an overlooked value and power in the ecologies of underdevelopment and the territories of pre-states, as the potential index and fruitful path to support contemporary urban life in the future.

Acknowledgments

Several fields have influenced this project, and as a result, several practitioners from different camps, including different industries, organizations, and institutions, brought influence and inquiry to this project and its ideas.

A very early supporter of the research of this project was Charles Waldheim, former Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) and former director of the Landscape Architecture Program at the University of Toronto. Charles saw not only the potential for the line of inquiry proposed in this book but supported several key studios, seminars, and symposia, both at Harvard University and the University of Toronto, at several critical stages of development, providing important steps forward. Together with Mohsen Mostafavi, Dean of the Harvard GSD who built the foundation for design’s rappel-à-l’ordre at Harvard University and the renewal of the landscape project, they have accorded considerable time, latitude, and funding to complete this project and cultivate its audience.

Albeit in an unsolicited way, thanks to Neil Brenner, a geographer from New York who joined the GSD in 2012 due to the initiative of Mohsen Mostafavi and Charles Waldheim. Neil has provided capstone mentorship and intellectual feedback as this project reached maturity. While I contend that theories are for the blind, he alternatively argues that everyone is a theorist, in turn promoting the need to go deep into cultural thinking while resurfacing for air. Neil helped confirm the relevance of the infrastructure subject through the field of landscape and its influence on the discipline of geography in North America. He also underscored the influences and extremes in geographic knowledge and discourse between the United States (a country that saw the closure of its geography departments from the 1930s onward) compared to the geographic culture and geospatial literacy of countries of the Commonwealth such as the UK, Australia, Singapore, Nigeria, India, and Canada, where geographic knowledge has been more pervasive early on, and from where geographic information systems were conceived and innovated. When arriving in Cambridge, Michael Van Valkenburgh and Antoine Picon from the Harvard GSD and L’École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées, as well as Alan Berger from MIT, provided unbiased advice at key moments that helped strategize this project. Their work, and their words, through conversations and courses, have had important influence on the combined polemical, political, technological, and popular dimensions that design disciplines often overlook.

Throughout the past few years, several key colleagues have also strongly influenced this project, both directly and indirectly. It is their unsolicited influence, as practitioners and pedagogues from the Harvard Graduate School of Design and the University of Toronto, that has enabled every minute of every day to be one long, open, extended conversation.

Additional colleagues at the Harvard GSD whose influence bears importance include Nina-Marie Lister, Hashim Sarkis, Chris Reed, Gary Hilderbrand, Niall Kirkwood, Sonja Duempelmann, Richard T.T. Forman, Anita Berrizbeitia, and Patricia Roberts.

Thanks to the guest speakers who participated in two separate conferences, the most recent at the GSD in 2012: Kate Ascher (Happold Consulting), Sabine Bar-les (Université Paris 1), Liz Barry (PLOTS), Peter Del Tredici (Arnold Arboretum-GSD), Erle Ellis (UMBC), Christophe Girot (ETH Zurich), Wendi Goldsmith (Bioengineering Group), Jo Guldi (Harvard Society of Fellows), Kevin S. Holden (USACE), Eduardo Rico and Enriqueta Llabres (Relational Urbanism Design Studio, ARUP), Todd Shallat (BSU), Kevin Shanley and Ying-Yu Hung (SWA), Dirk Sijmons (TU Delft), Rosalind Williams (MIT), and Dawn Wright (ESRI); and the second, in 2009 at the University of Toronto: Stan Allen (Princeton), George Baird (Toronto), Julia Czerniak (Syracuse), Herbert Dreiseitl (Atelier Dreiseitl), Kristina Hill (UCB), Michael Jakob (HEPIA), Nina-Marie Lister (Ryerson University), Kate Orff (Columbia), and Jane Wolff (University of Toronto) as well as plenary discussions with Rodolphe el-Khoury, David Fletcher, Ted Kesik, Robert Levit, Liat Margolis, Alissa North, Mason White, and Robert Wright. Both events contributed enormously in helping to bring the subjects of ecology, economy, and engineering closer together, through design, as well as to lay out the groundwork for future collaborations and projects together. They serve as a reminder that we have only begun scratching the surface of the infrastructure subject and landscape’s tremendous potential.

Dr. Ted Kesik, building scientist and environmental engineer, as well as Professor Robert Wright, landscape architect and ecological planner from the University of Toronto, provided the initial impetus for this project very early on, in its pre-doctoral stage. Both of them proposed that the measure of influence of this work should find itself on the shelf of the T Section (technology and engineering) of the university’s main library, in the hands of engineers who equally stood to gain from this research—that, in addition to the more common NA and SB sections (architecture and landscape), where the book would naturally find a home. Their influence during the incubation period of this project was important.

In addition to their influence, George Baird and Larry Richards provided sustained guidance to research and develop this thinking while at the University of Toronto. Equally, Brigitte Shim, John Danahy, Emily Waugh, Jane Wolff, and Mason White constantly engaged this discussion in reviews, lectures, and presentations. Fred Urban provided much encouragement exactly over years ago for the directions proposed here that, albeit experimental some time ago, have become more widely accepted and common today. During those years, Michael Hough was the intellectual entrepreneur who provided precedents and alternative views at several key moments to the optic on infrastructural practices seen through the development of his office and organization, which has undergone an unprecedented level of growth and influence as a large-scale enterprise.

Several fields have influenced this project, and as a result, several practitioners from different camps, including different industries, organizations, and institutions, brought influence and inquiry to this project and its ideas.

A very early supporter of the research of this project was Charles Waldheim, former Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) and former director of the Landscape Architecture Program at the University of Toronto. Charles saw not only the potential for the line of inquiry proposed in this book but supported several key studios, seminars, and symposia, both at Harvard University and the University of Toronto, at several critical stages of development, providing important steps forward. Together with Mohsen Mostafavi, Dean of the Harvard GSD who built the foundation for design’s rappel-à-l’ordre at Harvard University and the renewal of the landscape project, they have accorded considerable time, latitude, and funding to complete this project and cultivate its audience.

Albeit in an unsolicited way, thanks to Neil Brenner, a geographer from New York who joined the GSD in 2012 due to the initiative of Mohsen Mostafavi and Charles Waldheim. Neil has provided capstone mentorship and intellectual feedback as this project reached maturity. While I contend that theories are for the blind, he alternatively argues that everyone is a theorist, in turn promoting the need to go deep into cultural thinking while resurfacing for air. Neil helped confirm the relevance of the infrastructure subject through the field of landscape and its influence on the discipline of geography in North America. He also underscored the influences and extremes in geographic knowledge and discourse between the United States (a country that saw the closure of its geography departments from the 1930s onward) compared to the geographic culture and geospatial literacy of countries of the Commonwealth such as the UK, Australia, Singapore, Nigeria, India, and Canada, where geographic knowledge has been more pervasive early on, and from where geographic information systems were conceived and innovated. When arriving in Cambridge, Michael Van Valkenburgh and Antoine Picon from the Harvard GSD and L’École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées, as well as Alan Berger from MIT, provided unbiased advice at key moments that helped strategize this project. Their work, and their words, through conversations and courses, have had important influence on the combined polemical, political, technological, and popular dimensions that design disciplines often overlook.

Throughout the past few years, several key colleagues have also strongly influenced this project, both directly and indirectly. It is their unsolicited influence, as practitioners and pedagogues from the Harvard Graduate School of Design and the University of Toronto, that has enabled every minute of every day to be one long, open, extended conversation.

Additional colleagues at the Harvard GSD whose influence bears importance include Nina-Marie Lister, Hashim Sarkis, Chris Reed, Gary Hilderbrand, Niall Kirkwood, Sonja Duempelmann, Richard T.T. Forman, Anita Berrizbeitia, and Patricia Roberts.

Thanks to the guest speakers who participated in two separate conferences, the most recent at the GSD in 2012: Kate Ascher (Happold Consulting), Sabine Bar-les (Université Paris 1), Liz Barry (PLOTS), Peter Del Tredici (Arnold Arboretum-GSD), Erle Ellis (UMBC), Christophe Girot (ETH Zurich), Wendi Goldsmith (Bioengineering Group), Jo Guldi (Harvard Society of Fellows), Kevin S. Holden (USACE), Eduardo Rico and Enriqueta Llabres (Relational Urbanism Design Studio, ARUP), Todd Shallat (BSU), Kevin Shanley and Ying-Yu Hung (SWA), Dirk Sijmons (TU Delft), Rosalind Williams (MIT), and Dawn Wright (ESRI); and the second, in 2009 at the University of Toronto: Stan Allen (Princeton), George Baird (Toronto), Julia Czerniak (Syracuse), Herbert Dreiseitl (Atelier Dreiseitl), Kristina Hill (UCB), Michael Jakob (HEPIA), Nina-Marie Lister (Ryerson University), Kate Orff (Columbia), and Jane Wolff (University of Toronto) as well as plenary discussions with Rodolphe el-Khoury, David Fletcher, Ted Kesik, Robert Levit, Liat Margolis, Alissa North, Mason White, and Robert Wright. Both events contributed enormously in helping to bring the subjects of ecology, economy, and engineering closer together, through design, as well as to lay out the groundwork for future collaborations and projects together. They serve as a reminder that we have only begun scratching the surface of the infrastructure subject and landscape’s tremendous potential.

Dr. Ted Kesik, building scientist and environmental engineer, as well as Professor Robert Wright, landscape architect and ecological planner from the University of Toronto, provided the initial impetus for this project very early on, in its pre-doctoral stage. Both of them proposed that the measure of influence of this work should find itself on the shelf of the T Section (technology and engineering) of the university’s main library, in the hands of engineers who equally stood to gain from this research—that, in addition to the more common NA and SB sections (architecture and landscape), where the book would naturally find a home. Their influence during the incubation period of this project was important.

In addition to their influence, George Baird and Larry Richards provided sustained guidance to research and develop this thinking while at the University of Toronto. Equally, Brigitte Shim, John Danahy, Emily Waugh, Jane Wolff, and Mason White constantly engaged this discussion in reviews, lectures, and presentations. Fred Urban provided much encouragement exactly over years ago for the directions proposed here that, albeit experimental some time ago, have become more widely accepted and common today. During those years, Michael Hough was the intellectual entrepreneur who provided precedents and alternative views at several key moments to the optic on infrastructural practices seen through the development of his office and organization, which has undergone an unprecedented level of growth and influence as a large-scale enterprise.

Students from graduate courses at several institutions—Harvard GSD, University of Toronto, BOKU University in Austria, IAAC in Spain, AA in London, TU Delft and Wageningen University in the Netherlands—and several other universities across North America, who performed as unsung institutional stuntmen and pedagogical guinea pigs, put to the test curricular methods, constantly asking critical questions in seminars and studios, exposing holes, gaps, and omissions through their inquiries, while seeing potentials, establishing connections, and drawing bridges to new dimensions, without judgment. It is those questions that open up new areas of investigation, and those questions should always keep coming.

Those graduate students who became collaborators at OPSYS and the Landscape Infrastructure Lab helped conceive, incubate, express, and research different ideas, while developing, materializing, and implementing strategies: Alexander S. Arroyo, Behnaz As-sadi, Daniella Bacchin, Anne Clark Baker, Chen Chen, David Christensen, Joshua Cohen, John Davis, Hana Disch, Kelly Doran, Kimberly Garza, Alexandra Gauz-za, Stephan Hausheer, Luke Hegeman, Tawab Hlimi, Brett Hoonaert, Sara Jacobs, Deborah Kenley, Kees Lokman, Fadi Masoud, Hoda Matar, Christina Milos, Aisling O’Carroll, Erik Prince, Maya Przybylski, Pamela Ritchot, Curtis Roth, Daniel Seiders, Andrew tenBrink, Sarah Thomas, Elena Tudela, Jacqueline Urbano, Ed Zec, and Chris de Vries.

This work would have been impossible without influence from industry and boards that I had the privilege and opportunity to serve on. From different company representatives and managers who provided unfettered access to sites and records, from floodplains to food terminals to landfills: Renata von Tscharner (Charles River Conservancy), Brian Ezyk (Republic Services, Inc.), Bruce Nicholas, Gianfranco Leo, and Gary Da Silva (Ontario Food Terminal Board), Alexander Reford (Jardins International de Métis), Chris Rickett (Toronto and Region Conservation Authority), and more recently to Kevin Holden, from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, who opened a huge area of latent collaboration that has been dormant for decades. Together, they have identified the great responsibility upon the practice of landscape architecture to address challenges of large-scale projects and the finer-grain details of standards and specifications that engineers typically work with.

On several occasions, mostly through short but influential exchanges, in airports, emails and elevators, James Corner (Field Operations), Adriaan Geuze (West 8), Jack Dangermond (ESRI), Joe Brown (AECOM), Rem Koolhaas (OMA/AMO), Winy Maas (MVRDV), Ben van Berkel (UN-Studio), George Hargreaves (Hargreaves Associates), Joe Miotto and Elizabeth Starr (NORR), Bill Hewick (ACME Environmentals), Dirk Brinkman (Brink-man & Associates Reforestation), Martha Schwartz (MSP), Gary Pilger (Pilger Equipment), Wendi Goldsmith (Bioengineering Group), and Tyler Ginther (Super Soil) provided memorable advice in pursuing dirt research with practical applications.

Several funding organizations helped support several events and related endeavors, including Harvard GSD, University of Toronto Daniels School of Architecture, Landscape, and Design; Landscape Architecture Canada Foundation; Netherlands Architecture Fund; Ontario Sand, Stone & Gravel Association; Canada Department of Natural Resources; the Ontario Ministry of Northern Development, Mines and Forestry; Canada Foundation for Innovation, Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council; Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council; and the Canada Golf Foundation. The Norman T. Newton Prize from Harvard University provided me with a copy of Norman T. Newton’s Design on the Land: The Development of Landscape Architecture (Harvard University/Belknap Press, 1971), an important book whose raison d’être highly influenced my thinking about the discpline of landscape architecture (and its undiscipline), through how land is constructed and cultivated, neglected or abandoned, designed and engineered, territorialized and deterritorialized, colonized and decolonized.

I would like to thank Prof. Jusuck Koh for his initial invitation to develop this writing into doctoral research at the University of Wageningen, the premier institution for studies in life sciences and agricultural research in the world. His support was catalytic, and was sustained for more than five years in pursuit of its underlying thesis. Taught by Ian McHarg at the University of Pennsylvania, Professor Koh provided an open and critical forum and a theoretical platform—the classroom as a lab—for unlocking several key ideas and concepts presented here. Without his initial invitation to Wageningen in 2006 for a conference on contemporary landscape urbanism, this project would have taken a very different direction. Unknowingly, the project saw the intellectual influence of Sabine Barles (Université Paris 1), Kelly Shannon (AHO School of Architecture), Dirk Sijmons (TU Delft), Anemone Koh (Oikos), Bert Holtslag (WUR Meteorology), and Arnold van der Valk (Wageningen University), who shaped the central idea of this book through the influence of their work and writing on the multilayered landscape of infrastructure, conveyed through histories, ecologies, myths, infrastructures, and urbanisms of water over the past few years. The concluding notion that “form follows fluidity,” as the contemporary inflexion of the historic adage “form follows function,” is a direct outcome of their profound influence. Thankfully, they all accepted Professor Koh’s invitation and generously agreed to form the Doctoral Review Committee, sharing their time through focused feedback and critical support.

Informal, raw conversations during experiences and exchanges with friends are the unspoken contributions to this project: Peter and Alissa North, Shane and Betsy Williamson, Leslie Lee and Wynne Mun, Maximo and Janine Rohm, Nazrudin Hiyate, Ricardo Pappini, Luc Dandurand, Louis Martin-Villeneuve, Hans Joseph, and David Lavictoire. In different ways, they all helped test and shape ideas presented here.

Gloria I. Taylor, Jacob and Yoshiko Mazereeuw defied distance and supported this effort through all its developments and discoveries. And, finally, an incalculable debt is owed to Miho and Nina, whose unquestioned and unconditional support provided the greatest level of love, balance, and intelligence that seeded and sustained the project, bringing it, and many new possibilities to life.