Home is a pretty good place to be.

JIMMY WEBB

It’s obviously not necessary to meet a person in order to have an opinion about them, or indeed their records, and in some cases it’s probably best not to. There are artists whose music I love but whom I don’t especially want to meet in case I don’t like them, but there are some people you’d fall over yourself to meet. Obviously it’s rarely the waifs and strays you want to talk to, it’s the bona fide legends. And you want the experience to produce two things: selfishly you want the encounter to give you a greater understanding of their personality (and – a great failing in a journalist, I know – privately you want to like them, too), and professionally you want to walk away with sufficient secrets to build on the established understanding of their work.

I have interviewed enough celebrities to know that, from the moment we meet, there is often a kind of war of attrition between us. Because they are famous they have usually created a self – a self that is not completely them, but curiously is not not them either. Which is what the journalist and profile writer Thomas B. Morgan noted back in the mid-sixties: ‘Most better-known people tend toward an elegant solution of what they, or their advisors, call “the image problem”,’ he said. ‘Over time, deliberately, they create a public self for the likes of me to interview, observe, and double-check. This self is a tested consumer item of proven value, a sophisticated invention, refined, polished, distilled, and certified OK in scores, perhaps hundreds of engagements with journalists, audiences, friends, family, and lovers. It is the commingling of an image and a personality, or what I’ve decided to call an Impersonality.’

These days, impersonalities have become so successful that it’s nigh on impossible to tell the difference between what is real and what is mediated. Often, because they are always ‘on’, some celebrities treat their impersonality as their real identity, their real character. And, as a lot of famous people decided long ago that fame was the only way to diminish, if not completely banish, their past, they are completely happy with this.

And, oddly, often we are, too.

I met Jimmy Webb in Wall’s Wharf, a large family seafood restaurant right on the water in Bayville that has been serving clams, oysters and fresh seafood to the people of Oyster Bay, on Long Island, for over sixty years. In the summer, you can’t move in here, but today, in the middle of October, Webb and I were the only customers. It is the perfect place to interview a man who wrote the quintessential song about the perennial loner. He lives nearby and this is where he comes if he wants a quiet coffee, some uninterrupted CNN or a slow walk along the beach. This part of Long Island, with its yachts and its big dogs and its white clapboard houses, has become something of an enclave for the musical fraternity, and as well as Billy Joel and Jimmy Webb, the late John Barry lived here, just up the road from rock fan John McEnroe and literary recluse Thomas Pynchon (not that anyone ever saw him).

Webb is still a tall man, and he hasn’t been diminished by time. He wore a black hoodie, black track pants, a grey T-shirt and charcoal sneakers. He sported an Apple Watch, but would probably hate it if you mentioned this. He was engaging, serious, matter-of-fact and fearsomely bright – not so fearsome that he rams his intellect down your throat, but he’s smart. He mostly frowned, in the way that very successful people reserve their smiles for moments that genuinely please them, but when he did smile, you caught a fleeting glimpse of the young Jimmy Webb, the naive songwriter who embraced stardom with an open face and wide-eyed Midwestern wonder. If this was an impersonality, it was certainly one I could work with.

Webb still tours regularly, performing around fifty concerts a year in the US, Australia and Europe. His concerts since Glen Campbell’s death have been complicated, however, because he can tell that many of those who come to see him want him to somehow carry Campbell’s mantle. He has even been performing some shows with Campbell’s daughter, Ashley. ‘It’s tinged with a kind of bittersweet joy,’ said Webb, who admitted the loss of Campbell is still too painful for him to discuss. ‘I love doing his music because it keeps Glen’s spirit alive. And not to sound too weird about it, I feel Glen around during those performances. I have to ride herd on my emotions when I’m singing because it’s just over a year since we lost him and the sense of loss is still very acute and it’s very fresh. I can see his face and hear his voice when I’m doing my lame attempts of doing “Wichita Lineman”. But all in all, it’s a positive experience.

‘As long as I’m alive he’ll never be forgotten. I will always play Glen Campbell music. I will keep that candle lit. We lost a tremendous talent. And we only scratched the surface of what he was capable of achieving … I believe in the Greek idea that as long as someone is saying your name, you remain alive. I am keeping his legacy alive. But I also perform because it keeps me alive.’

He is as protective of Campbell as the singer once was of him. ‘First of all, we were close. Our families really grew up together, our kids are like best friends. Glen’s kids, my kids and Harry Nilsson’s kids have all coalesced into this big extended family, and so we are protective of each other. There was a hostile element in the press that pretty much dissed him as a right-wing sort of Establishment character, and by association labelled me as a middle-of-the-road songwriter dotard. And Glen had my back from day one. I wanted – and still strive – to let people know that he was a genius, that he wasn’t just an easy-going country boy. I mean, Donald Trump said that one of the reasons he doesn’t like the attorney general, Jeff Sessions, is because he has a southern accent, and a southern accent makes him sound stupid. Now, that’s coming from a guy who’s no Einstein, OK? So, there it is right out in the open, the kind of big-city, intellectual attitude towards people from south of the Mason–Dixon Line: that they are not quite as bright.

‘I think Glen should be in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Research is ongoing, but nobody knows how many records he played on, nobody knows. Certainly hundreds, possibly thousands. A friend of mine has got a bunch of Kingston Trio records and he’s listening to a song one night called “Desert Pete”, and it’s a folk tale about a guy who’s going across the desert who finds a jug of sparkling water in this hole in the ground, and there’s a note from Desert Pete that says, “Drink all the water you can hold, fill the jug and leave it for somebody else.” So it’s a morality tale. He was listening to it one night and he thought he heard Glen on guitar. And he was right. There’s a really hot banjo part in the foreground of the record, shredding it. It’s clearly the motor that is driving this record, and I said, “It sure does sound like him to me.” We put it on and played it again and we started listening to the harmony, and clear as a bell I could hear Glen’s high tenor on the top note of the harmony part. And I said, “Yeah, it’s him, because he is singing harmonies.” So nobody knows how many of those things are out there. For years there’s been this thing called “Nashville Approved”, and there’s a legend that Glen was always kept off the list because he was so much of a better guitar player than anyone else.’

Jimmy Webb is, fundamentally, good company, an old-fashioned liberal gentleman with exceedingly good manners. We talked for hours, and the only blip was when I mentioned an old sweetheart. I hadn’t expected him to be tetchy, and he wasn’t – not until I mentioned Susan Horton, that is, the woman who broke his heart, and the unwitting muse for at least half a dozen of his most famous songs. I mentioned her simply because I wanted to know how she felt about being responsible for some of the most heartbreaking songs ever written. However, my question went down badly, as though I’d just mentioned the one thing I had been warned not to address, like the acrimonious divorce, the ill-judged investment or the never-referred-to brush with the law. Webb looked at me as though all the trust and all the equity that we’d built up together over the last ninety minutes had just evaporated right there in front of us, rising up above the oysters, the scallops and the Cobb salad. But although it briefly created an atmosphere, I was impressed that a scarred heart could still be causing problems over fifty years since it first started to hurt. Wow, this woman had really skewered him, so maybe it was no surprise that the songs were so good. He stopped sipping his coffee for a second and uttered a long, low ‘Noooow … Was she flattered? Oh, I don’t know, what girl wouldn’t be flattered? She used to tell me that it kind of embarrassed her, when it was too on point, like “Where’s the Playground, Susie?” I don’t know how the word got out that it was a real person named Susie Horton, but journalists will be journalists and people started asking me, “Was this a real person?” And I would say, “Yes,” and then try to move on. I actually think she became quite proud of the fact, as time went on. But I had it bad. It tore me up pretty badly when she announced that she was getting married. I remember going up to Tahoe and getting her one time. Going up there, she says I kidnapped her, but in this age that we live in, this Me Too movement, I really wish she wouldn’t say that because I really didn’t, I really didn’t kidnap her. I was just ardent. If I kidnapped her, why did she live in my house for two years? She ended up in the sack with my best friend, and that’s ultimately why we broke up, and I got rid of him, too.’

He had nothing but good things to say about his most famous song, nothing but good things to say about Glen Campbell, while reserving his ire for the US president and the carelessness of the record industry. He understands that the business has changed, although he’s not doing cartwheels.

‘Music does change, and it changes into something that you don’t want to do. It doesn’t change into something that you can’t do, because it’s childishly simple. Now they are running programs through AI computers that just have the template for a hit record, and they are trying to get computers to write. They are doing this – it’s not the ravings of a lunatic. I’ve been on the board of directors of ASCAP [the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers] for over twenty years, ever since Napster, from the bitter beginnings of this whole depredation that has been perpetrated by digital interests to devalue copyright and to really put us out of a job. Because they don’t want to have to deal with people, it’s easier just to have a room full of servers to write the music. They don’t have any chords, they don’t have any melodies, they don’t have any lyrics. Those are all the things that I’m interested in – I mean, incredibly interested in. Totally absorbed with, dedicated, in the deepest part of my being. I’m a creature that just deals with chords, melody and halfway decent lyrics.’

On 8 August 2017, Glen Campbell eventually succumbed to Alzheimer’s disease, in Nashville, his adopted spiritual home, aged eighty-one. In 2011, the year of his diagnosis, he released the album Ghost on the Canvas and announced that he would continue with his planned shows, regardless of his illness. Inevitably, the tour turned into a long goodbye, and the original five-week run turned into a marathon that included 151 shows in fifteen months.

‘I don’t know anything about it because I don’t feel any different,’ he said at the time. ‘The stuff I can’t remember is great because it’s a lot of stuff I don’t want to remember anyway. Does it get harder breathing new life into those old songs? No, every night is different. I got to know Sinatra quite well, and that’s what he tried to do. Every song was a unique performance. I still love “Gentle on My Mind”, and “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” still makes me real homesick. I’ve been very lucky in my career. For my whole life I felt like I was at the right place at the right time. It seemed like fate was always leading me to the right door.’

Campbell was post-rehab golfing buddies with Alice Cooper, and they used to play together regularly when they weren’t on tour. (‘He was a master short game player,’ said Cooper. ‘The best I ever played with.’) Cooper knew something was wrong with his friend when he started repeating himself on the golf course, telling him a joke when they teed off, and then telling it again at least twice before the end of the round. ‘That’s when I knew something was up,’ said Cooper. ‘But give him a guitar and he was a virtuoso.’

‘I didn’t care for golf,’ said Webb, ‘and I wouldn’t be caught dead with a golf club in my hand, unless there was a very poisonous reptile nearby. Glen bought me a set of golf clubs once. He’d say, “How you getting on with the clubs?” “Not so good, Glen …” He was an Orange County Republican. It’s a snotty thing to say, but they were around back then, and that’s what we called them. Bob Hope. John Wayne. The enablers of the Vietnam War mentality. John Wayne mixing with the Green Berets. Bob Hope going over there to rouse them. Sending out this signal that we’re winning this thing …’

When Campbell died, there were eulogies for months. ‘He had a beautiful singing voice,’ said Bruce Springsteen. ‘Pure tone. And it was never fancy. Wasn’t singing all over the place. It was simple on the surface but there was a world of emotion underneath.’ A few years beforehand, Amanda Petrusich wrote this lovely reminiscence in the New Yorker: ‘I met Campbell once, at the Nashville airport. All of my belongings (including my laptop, which contained an early and otherwise unsaved draft of a magazine feature I’d spent months reporting) had recently been stolen from my rental car. It was parked in a garage downtown; one of its rear windows had been smashed in with a rock. During the ensuing hubbub – phoning the cops, explaining the compromised state of my Kia Sephia to the rental-car agency – my flight back to New York City had departed without me. I was consoling myself by drinking a great deal of beer at an outpost of Tootsie’s Orchid Lounge, the famed Broadway honky-tonk. This must have been in 2009.

‘I looked up and saw Campbell wandering around with his wife, Kim Woollen. (They’d met on a blind date – he took her to dinner at the Waldorf-Astoria, with his parents, and then to a James Taylor concert.) Campbell hadn’t been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s yet, not in any official capacity, but it was clear, even then, that he wasn’t quite himself – that certain ideas or bits of language were receding, drifting out of reach, like paper boats fluttering across a pond.

‘I approached and brazenly asked for a photograph – I suppose I felt like I had little left to lose in Nashville that afternoon. They were so gracious. You know, it wasn’t that bad, losing my stuff and missing my flight. There would be more stuff, more flights. He threw a big arm around me and we grinned.’

Jimmy Webb was in close contact with Campbell during those final years, and he said that towards the end just about the only coherent phrases Campbell could muster were song lyrics, presumably through muscle memory. It broke his heart to see his friend this way, but he didn’t see how he could not visit him. After all, they had spent a lifetime together, on and off. ‘They’ll remember a song after everything else is gone,’ he told me. ‘They’ll remember the lyrics. They’ll remember the melody. They’ll be staring out the window blankly. Then they’ll burst into song.’

The day Campbell died, Webb released a statement, some of which is here:

Let the world note that a great American influence on pop music, the American Beatle, the secret link between so many artists and records that we can only marvel, has passed and cannot be replaced. He was bountiful. His was a world of gifts freely exchanged: Roger Miller stories, songs from the best writers, an old Merle Haggard record or a pocket knife.

He gave me a great wide lens through which to look at music. The cult of The Players? He was at the very centre. He loved the Beach Boys and in subtle ways helped mould their sound. He loved Don and Phil [Everly], Bill Medley and Bobby Hatfield, Flatt and Scruggs. This was the one great lesson that I learned from him as a kid: Musically speaking nothing is out of bounds.

One of his favourite songs was ‘Try A Little Kindness’ in which he sings ‘shine your light on everyone you see’. My God. Did he do that or what? When it came to friendship Glen was the real deal. He spoke my name from ten thousand stages. He was my big brother, my protector, my co-culprit, my John crying in the wilderness. Nobody liked a Jimmy Webb song as much as Glen!

Jimmy

For over fifty years, Jimmy Webb has been dealing in crushed broken hearts, with his songs acting like road maps, route maps, lovingly drawn directions to somewhere where life is better. In Webb’s heart, everything is a picture. ‘When I think about those days, the only way I can imagine them is sort of with a picture. I can see a house by a road. That’s the only way I can recall it.’

He holds his most famous song in great affection, and while he occasionally says that he won’t perform it again, he always does, even more so now that Glen Campbell has passed. He has told the story of its birth so many times now that it has taken on a life of its own, folded into a kind of parallel narrative. Today, however, on Long Island’s North Shore, in search of a definitive version he stopped to analyse every well-worn anecdote, every half-truth, every automatic response.

‘I suppose the story is this,’ he said, with as much care as he could muster. ‘It was written about the Oklahoma Panhandle, which was really the Cherokee strip [the sixty-mile stretch of land south of the Oklahoma–Kansas border], where the Cherokee lived until we decided we would take that away from them, because that’s what we did. We gave them things and then took them away again. This area is completely flat, and at the western end is New Mexico, the badlands, and to the south is West Texas, and it’s all pretty much desert. [In 1966, Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood was published by Random House, its opening sentence reflecting much about how Kansans, inhabiting one of the most lonesome places in the country, saw themselves.] There’s this little town right at the western end of the Panhandle called Boise City, and they say you can stand in Boise City and see into New Mexico, which is about fifty miles away, so the land really falls off. There’s this huge distance, and it is very desolate. There is an occasional hog farm or maybe small dwelling, nothing you would recognise as anything other than very, very small towns. The rest of it is almost like a scene out of a fifties western, with a wagon train going out across the plains. The only thing that’s visible is these telegraph poles and the wires between them. It’s so remote and it’s so quiet, with no one moving, that you can actually pull your car up by the side of the road, which my father actually did for me one day and said, “Come with me and listen.” And he walked with me under the lines, under the wires, and they were singing. They were actually making this musical sound, out there in the middle of nowhere. Electricity actually makes noise as it’s going through the wires, which is a little bit insane when you think about it, but it does make a noise if you’re in a place where it’s quiet. Whether it’s the resistance of the wires and the electricity overcoming that as it pushes through … It’s a frequency modulation of some kind.

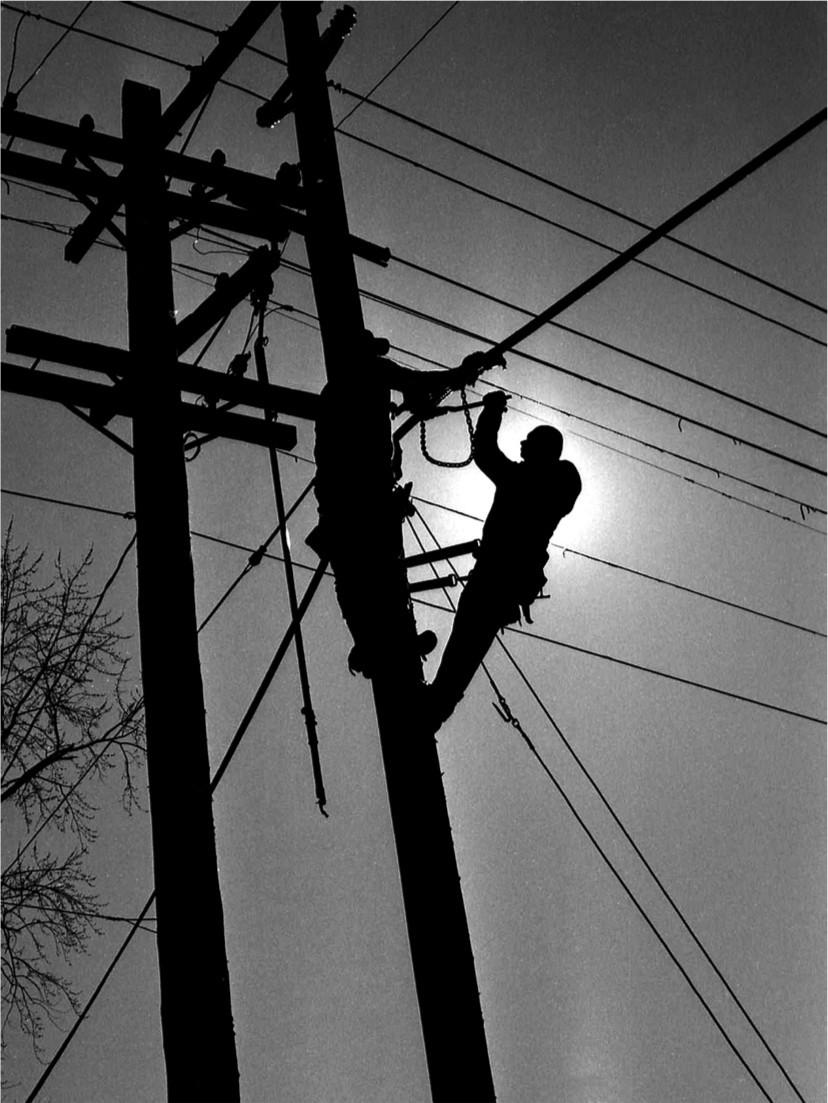

‘We would drive along these roads and see these guys out there, with their truck parked, and there’s not a soul around for ten, fifteen, twenty-five miles. There’s not a soul moving, except for hawks and little rabbits and things like that. Creatures of the plains. You’d see the occasional automobile, so what I was after in the song, I was after that sort of loneliness. It really goes hand in hand with the idea that it’s so quiet out there that you can hear the wires making this noise.

‘I think it’s fine that I didn’t finish it, because I don’t think it would have been as clean as it was, or as minimalist. It was sort of caught before any extraneous rococo could be added to it. It was sort of jerked out of the creative process and hot off the press. So there is a very minimalist quality to that record that complements the image of the high-wire guy, the lineman. His loneliness is this solitude that I witnessed first-hand.

‘Technically, I suppose the song is about the point where the Midwest meets the West. This is where the Santa Fe Trail used to head out for California, and you can still see the ruts out there of the wagons. So really, this is kind of the West and New Mexico, which is where all the outlaws went after they robbed the banks, you know. There was a lot of shooting and a lot of outlaws and stuff going on in Missouri and Oklahoma, and we refer to that whole genre as westerns, but you are right, it’s smack dab in the middle of the country. But it was a different time, when the West was closer to the centre of the country. As America expanded and more people moved west, so our idea of the West kept being pushed closer to the coast.

‘My family actually started in Virginia. Long ago, I traced my genealogy, using a Mormon genealogist out of Salt Lake City. I traced our family back through Alabama to Georgia to Virginia at the time of the Revolution, so when I look back at my DNA, I’m 61 per cent Irish. There is such a big fear of immigration in the country right now, but I wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for immigration, and my family have been here for two hundred years. This administration very conveniently forgets that every square foot of America was taken from someone by force, lethal force and cruelty beyond imagination. It isn’t like God prepared America for his special people, who came over and were white, but there are people here who sort of think that’s the way it happened. Every square foot, someone died for. Probably a brown person. Texas was stolen from the Spanish, California was stolen from the Spanish. If you read our history books, that’s not what you read. You read that there were wars, but they were predations by the Indians on the peaceful settlers. They gave them black hills in Dakota – for as long as the rivers run and as long as the sky is blue, as long as the hawk flies – until some knuckleheads found gold up in the hills, and then Custer was sent in there to drive them out.

‘So I sort of recognise my place in westward expansion. My genealogist said one time that the churchyards of Georgia are full of Webbs. “If you ever want to see your ancestors, go to Georgia,” he said. And in the Civil War, we were on the wrong side – my family were wearing grey. And so, when the family got to Oklahoma, little Jimmy was born. I was raised down in the south-west of Oklahoma and moved to West Texas, which was a hotbed for the whole rock and roll thing. I was a big Buddy Holly fan and soon decided I wanted to be a songwriter.’

And then he brought out that huge Midwestern smile, before settling on an even bigger Midwestern frown.

‘There’s lots of Wichitas. If you look at a map of the Midwest, there is a Wichita, Kansas, a Wichita, Oklahoma, there’s a Wichita, Texas. There’s also very prominently a Wichita River, and the battle of the Wichita River was a massacre. George Armstrong Custer rode in at dawn on a defenceless village. All the men were out hunting; it was winter. Every living thing – every woman, every child, every fucking dog – he killed everything that moved in that village, and the army had the temerity to call it the battle of the Wichita rather than the massacre at Wichita. But in my mind I decided that’s where it was – in Wichita, in Kansas. The song was about many places in the area, but it’s set in Wichita, Kansas. That’s it.’

He stopped for a while to consider again how he felt when he wrote it, and a thought occurred to him, one he couldn’t remember having before. ‘Maybe for a while it was “Arkansas Lineman”, but who knows? The way I work, I’m moving so fast that unless I had my notes, unless I had actually the pieces of paper that I had on the piano that day, I couldn’t say whether it was originally “Arkansas Lineman”. I never went through that because it was like releasing an arrow.

‘These days it takes me a lot longer to write a song, because you get to the point where you measure everything. Once you realise you are going to be judged on everything, you measure everything. You go, “Do I really want to use that word? How is that going to play?” you know? “Do I really have the right wires on top of this telephone pole?” Because when I wrote the song, I didn’t know; I didn’t know that much about the technicalities of being a lineman.’

While the Oklahoma Panhandle might be short of landmarks, it is not short of history, a no-man’s-land that no state wanted, a haven for outlaws and vigilantes. It still feels a little like that, and the roads here are no different today to how they were in 1968. As you drive west along Highway 412 – a relatively recent addition to the highway system – for instance, the road really does go on for ever. I needed to see for myself, and when I did, I wasn’t disappointed. To look at these roads, these poles, this sky, it’s easy to think that nothing much has changed in the fifty years since Jimmy Webb wrote about them. It’s the same on the dirt roads. In this part of the country, in this sacramental place, all you can really see is sky, as the floor below is almost incidental, a wide yellow mass of scrub broken only by hundreds, thousands of telegraph poles. There is simply nothing here, only distance, and the sensation of being completely alone. It’s unsettling, but also strangely empowering. Out here, in the mythical, physical West, your only friend is the radio, your only respite from heat, sky and memory. Driving out here is not so dissimilar from driving along Route 66, where it’s easy to imagine yourself hauled back in time to a place before the Interstates, when the only way to get from A to B was to start early. It is desolate. Sure, it is romantic and gives you a sense of existential ennui, but mainly it is desolate. There is wheat, and there is tumbleweed, and there is tarmac. And sky and poles and not much else. People have compared the experience of driving along these long stretches of road to being in a sensory deprivation tank, with nothing to see, smell, feel or hear, and at times the landscape can overwhelm you, almost becoming abstract as the miles keep building. The thing that keeps you going is the horizon, the never-changing, unforgiving horizon. Today that horizon is littered with wind turbines, which can make the telegraph poles that still flank the old routes look a little like old men staggering towards the county line, looking for home, rolling like crucifixes westward towards the coast, stoic and metronomic.

As ineffably joyful journeys go, the drive through Oklahoma is one of the best, as well as one of the longest, the roads snaking their way through one dustbowl town after another, concrete and asphalt ribbons down which millions of tourists once pushed their Detroit steel, looking for the new world or simply the definitive road experience. On the extraordinarily evocative drive west from Boise City to Guymon on Route 64, it’s not difficult to picture in one’s mind the hard times described in John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. Towns out here finish before they begin, fading into scrub. These are moonscapes of monstrous proportions, with two-lane blacktops cutting through them like charcoal arrows. To drive on Route 64 or Route 66, which runs parallel to the south, is to step back in time, to relive an age when driving was still an adventure, not a necessity. After World War II, when the car was still king, these roads that had once been the service roads to California became the stuff of fantasy. The country towards the west of Oklahoma can make you feel light-headed with solitude – creviced arroyos, harsh desert and wild bush scrub. ‘Sometimes, toward either end of a long driving day,’ wrote Tom Snyder in one of his roadside companions, ‘a run through this country brings up an ancient German word, Sehnsucht. It has no equivalent in English, but it represents a longing for, a need to return to, a place you’ve never been.’

It is a sensation that springs to mind when thinking about ‘Wichita Lineman’.

Here, in western Oklahoma, as the late afternoon starts to fold into the evening, and as shadow begins to add some context to the landscape, any feelings of deprivation – sensorial or emotional – are banished, as the sky takes over, morphing into a kaleidoscopic canopy.

The only constant is the telegraph poles, a glissando to the sea …

There are so many pictures in Jimmy Webb’s life, pictures that trace the career of a man who caught fame early and who mirrored its well-worn narrative arc before coming out the other side with a reputation the size of Mount Rushmore. Glen Campbell, too, had the same pictures, the ones of him as confident young buck who became so successful he even – for one year only, in 1968 – outsold the Beatles, before succumbing to those hoary old clichés of wine, women and dope. He, too, can still be seen on YouTube, pumping out his classic hits in his rehab years, wiser and with a stronger voice than ever.

Most of these pictures are good for both of them, although the images we like the best are the ones of them in their prime, in their pomp, when the world was at their feet and when their songs had found their way into our hearts for the very first time. We might not have fallen in love with ‘Wichita Lineman’ until the seventies, the nineties, the noughties, whenever; and we might not have fallen in love with it until last week, but we fell in love with it in its infancy. We love hearing Glen Campbell sing the original, and we love watching him sing it most when it was released, in 1968, when he was thirty-two and Jimmy Webb was still only twenty-one. The strongest image we have of Webb is the one where he sits cross-legged in his white turtleneck sweater, his white jeans and his little white boots. He has a Beatle cut, a hint of stubble, and wears an expression that could be sufficiently described as sanguine.

The image many love of Glen Campbell, or at least the one I love, is a still from his appearance on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour in 1968, where he performs ‘Wichita Lineman’ against a set composed largely of huge, angular telegraph poles that look as though they have been designed by Saul Bass. A sunset has been painted approximately on the backdrop. Campbell stands with one foot against the base of a pole, strumming what looks like a Fender Bass VI and smiling over the top of the camera, looking as though he’s peering up into the sky, forty feet above the ground perhaps. He’s wearing a modish brown suit, ankle boots and a pale-yellow roll-neck, perfectly groomed but also having the appearance of someone who has quite literally just walked in off the street.

Then, as the song reaches one minute and twenty seconds, he turns and looks directly into the camera, his matinee parting and the cleft in his chin telling you he means business. Show business. This was Glen Campbell’s face for the world to see. And maybe Jimmy Webb’s, too. Campbell blinks, feeling rangy and freewheeling, and then he drops the bomb, the bomb that never stops: ‘And I need you more than want you / and I want you for all time …’ And in the mind’s eye, the telegraph poles appeared to be flashing by in rhythm.

Having both taken a metaphorical trip along Route 66 to find fame and fortune, their greatest success would be an anthem celebrating the Midwest, the place where both of them were born.

Unsurprisingly, of all the recordings that Campbell made of Webb’s songs, ‘Wichita Lineman’ remains Webb’s favourite. ‘It was a perfect marriage between a song and a voice,’ he said. ‘It’s amazing today to listen to that record and realise how highly pitched his voice is, because all of our voices have dropped in the intervening years. But he sung so high and he was such a smooth singer, and there was a note – it was very plaintive, almost like a dying fall – to his intonation, to things that are almost indescribable, almost intangible. But I don’t think that the record has lost any gravitas since it was made. You put it on and it still sounds as though that song and that singer were meant to be together.

‘Over the years I’ve changed my mind a little bit about “Wichita Lineman”, as I’ve realised it must be better than I thought it was, but I always come back to the fact that I didn’t finish it. If I had finished it, it wouldn’t have been as clean. Because it was kind of an interrupted creative process, because Al De Lory wrote a sort of precognitive arrangement, and it was almost childishly simple. He was a minimalist before his time, before its time, and you can hear it on “Wichita Lineman”. Glen also has the perfect instrument for that song; it was absolutely written for his voice, and I knew exactly where his voice was on the piano. “Wichita Lineman” stands up as a record, it still sounds great. If it came on the jukebox right now in this place’ – he looked around the empty Wall’s Wharf bar – ‘bam! There is an immediate identification of that sound, that voice. There is a pairing between the song and the voice. I attribute a lot of its longevity to that, because it’s not really coloured by any particular era, just it’s a phenomenal record. The record is like a Picasso line drawing. I can say that because I didn’t make the record besides holding down the two notes on the church organ. They made the record, and Glen knew how to make records. He’d already made thousands of records. He had played on “Viva Las Vegas” with Elvis Presley, he’d done “You’ve Lost That Loving Feelin’”, he played on “Johnny Angel”. The depth of his knowledge of what to do in the studio, you can’t count that out. You can’t disregard that as a factor.

‘He came over to my house one day to watch a football game, and I put a record on that I had been toying with, by Allen Toussaint. I said, “Listen to this guy.” Some of his stuff was pretty far out; it was borderline, sort of psychedelic in a way. We finally came to “Southern Nights”, and he listened to it and with kind of a glazed look over him – he forgot all about the game – he said, “Can I have that?” And I said, “Don’t ask me, it’s Al Toussaint’s, it’s already recorded.” And he says, “No, can I have that record?” I said, “Well, I’m not really finished with it, but I guess so.” He grabbed it, and it was like a Warner Brothers cartoon – he went out the door like boom, like the coyote. Then a couple of weeks later it came on the radio, his version of “Southern Nights”, and it was a huge hit. Glen completely took it apart and put it back together again, and when he got finished with it, man, there was no doubt: when it came into a radio station it was going onto the turntable.

‘I have a kind of angst against people who try to diminish Glen as being any less of a musician than he was, any less of an intellect than he was. He was a record man, through and through, and he came up with those session players, the Wrecking Crew, so he had already sat through a hundred thousand sessions where they didn’t cut any hits, so he sort of knows what an un-hit sounds like. I gave him all the credit in the world for “Wichita Lineman”. He knew it was finished. Whether I knew it was finished or not, he knew it was finished.’

Call it a working-man blues, call it a hymn, call it people music, call it whatever you want. The beauty of ‘Wichita Lineman’, like the constant retelling of how Jimmy Webb came to write it, is in the repetition. ‘I’ve never worked with high-tension wires or anything like that,’ he said. ‘My characters were all ordinary guys. They were all blue-collar guys who did ordinary jobs. And they came from ordinary towns. They came from places like Galveston and Wichita and places like that.

‘No, I never worked for the phone company. But then, I’m not a journalist. I’m not Woody Guthrie, I’m a songwriter, and I can write about anything I want to. I feel that you should know something about what you’re doing, and you should have an image, and I have a very specific image of a guy I saw working up on the wires out in the Oklahoma Panhandle one time with a telephone in his hand talking to somebody. And this exquisite aesthetic balance of all these telephone poles just decreasing in size as they got further and further away from the viewer – that being me – and as I passed him, he began to diminish in size. The country is so flat, it was like this one quick snapshot of this guy rigged up on a pole with this telephone in his hand. And this song came about, really, from wondering what that was like, what it would be like to be working up on a telephone pole, and what would you be talking about? Was he talking to his girlfriend? Probably just doing one of those checks where they called up and said, “Mile marker 46,” you know? “Everything’s working so far.”’