On May 4, 1944, a day of early-summer heat in Rome, a man was brought to the Gestapo’s headquarters in the city. It was the ninth month of the German occupation. The HQ was located halfway up Via Tasso, a gently sloping street of cobbles and sand-colored apartment buildings in the San Giovanni quarter of the city center. The prisoner was Arrigo Paladini, a teacher of Latin and Greek. He was a scholarly, bespectacled man whose face wore the same look of chronic undernourishment that could be seen all over wartime Europe. On arrival at Via Tasso, SS police beat him with rubber hosepipes for eight hours. He scratched a diary—called il libro nero, the black book, into the blue-gray plaster of his cell wall. The only entries for the days in question, beginning on May 4, were botte, beatings, over and over again. The last entry was on June 4.

In the thirty days he was confined in the cell, the only light he saw entered through a small barred opening twelve by eighteen inches above the door. The stifling heat of the Italian summer and the ubiquitous Roman mosquitoes came in too. The German state security apparatus, headed by the Gestapo, had taken over the building in September 1943, and one of the first things they did was brick up almost all the windows in each room that had been converted into a cell. Only small openings were left for ventilation so the prisoners didn’t actually suffocate. But in the dark, Paladini managed to keep his diary on the wall with the help of a small nail. He also wrote other messages—including two lines of the Italian national anthem, and a long letter to his mother, to God, and to his girlfriend.

“Those whom I love infinitely I will leave as the guardians of my spirit, the last hope has not been lost, perhaps life is safe,” he wrote to his girlfriend. As a partisan caught smuggling radio equipment to and from Allied agents in Rome, it was a given that he would be condemned to death, and Arrigo also knew that his torturers would stretch out the process to gain as much information as they could before they executed him. What they most wanted to know were the names of his fellow partisans, and where they were hiding their secret radio sets, delivered to them by American agents from the OSS, the Office of Strategic Services, the precursor of the modern CIA. Crucially, they also wanted to know where in or around Rome the Americans were hiding.1

Paladini also wrote, in Greek, a well-known aphorism attributed to the philosopher Heroclitus: πάντα ῥεῖ, or “Panta Rhei,” meaning “Everything moves onward, nothing will remain still.” He was not the only one to leave messages scratched into the plaster. Another prisoner before him had written, “Facile saper vivere, grande saper morire” (It’s easy to know how to live, but a fine thing to know how to die).

Next to Paladini’s messages to his mother, God, and his girlfriend, there is a scratched line drawing of a rabbit, ears aloft, sitting on its hindquarters. “Beware,” says a scratched message alongside it, with an arrow pointing to one of Paladini’s quotes above it. “The Rabbit” was the code name for a double agent in Rome who had operated for both the Allies and the Germans, and Paladini suspected his true loyalties lay with the latter. He knew he had been betrayed. So, knowing that he was going to die, Paladini was leaving a message for any other partisan inmates who might follow him into the cell, or anybody who might read the messages. But was Paladini also hoping his warning would be read by his German captors, or by eventual Allied liberators? What is certain is that for a man as intelligent as Paladini, who could recite whole passages of Dante by heart, the message was not left for nothing.

When he was arrested by the Germans on May 3, Paladini was bringing radio equipment into Rome from the province of Abruzzo, northeast of the capital, where he was a partisan. The radio had been air-dropped by the Allies. Working as a senior partisan liaison officer with the American OSS mission in Rome, he had infiltrated his way into the capital and made contact with the underground cell. An informer had betrayed him, and he had been arrested in the Piazza delle Croce Rossa.

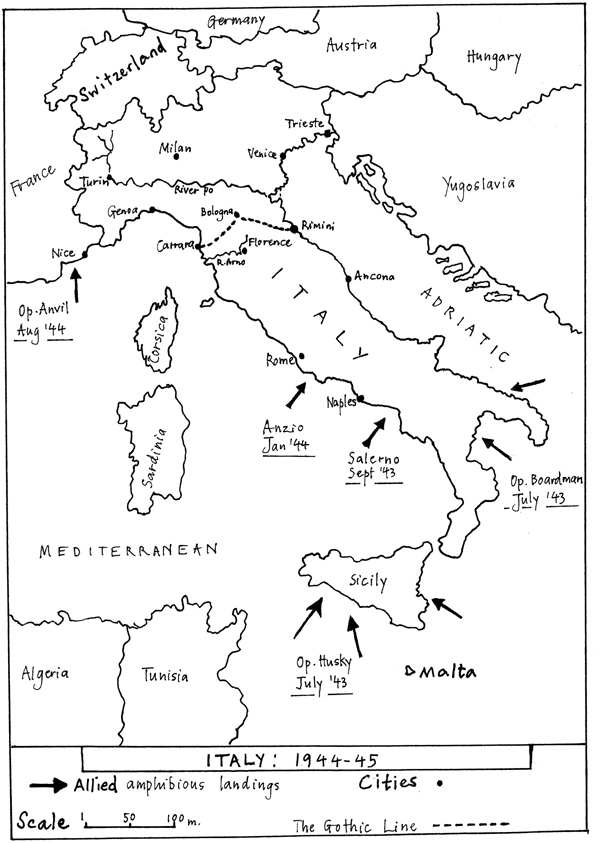

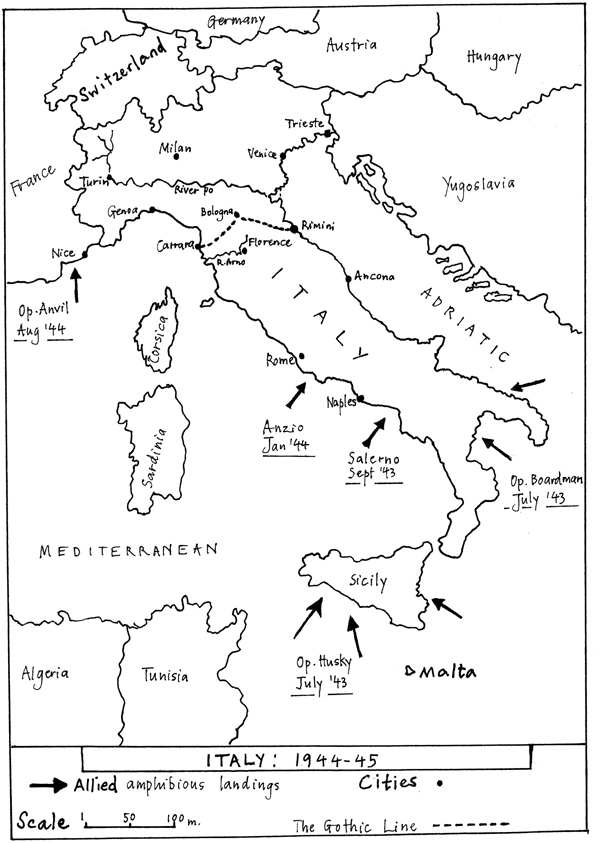

By early 1944, the huge Allied armies that landed in Sicily the summer before, and then on the Italian mainland at Salerno in September 1943, were bogged down south of Rome. The blood-soaked mountain bottleneck that was Monte Cassino had held up half of them, the beachhead at Anzio the other. But in German-occupied Rome, American and Italian agents from the Office of Strategic Services—the precursor of the modern CIA—were living and operating under cover, playing an incredibly dangerous game of cat and mouse with the Gestapo and the Italian Fascist authorities. The OSS operated in Italy alongside the British Special Operations Executive, or SOE, in running agents and supplying partisan groups operating behind German lines.

Under questioning, Paladini was saying nothing. So in addition to his beatings, the Germans put him on a starvation diet. One day, a fellow prisoner managed to sneak him a cup of dirty water that had been used for washing, the only traces of food in it some flecks of meat caught in the soapy foam at the top. Later in his confinement, to prevent him actually dying, he was given a few spoonfuls of broth every two days. He was told his father would be killed unless he talked, and his misery was compounded by guilt, thinking that his silence was condemning his father to death. (In fact Paladini Senior had died in a German prison on 25 October 1943.)2 Sitting in his cell, starving, beaten half to death, the partisan clung to a small spark of hope. Like everyone in Italy, he knew that it was only a matter of time before the Allied armies liberated Rome. So he scratched his desperate hopes on the wall of the cell: “Perhaps I will escape with my life.”

The Road to Rome

By late spring 1943, the Americans and British and their Commonwealth and colonial Allies had won the war in North Africa. The opening of a Second Front in northwest Europe was still a distant possibility, and the victory in Africa left the Allies in the Mediterranean with a choice of where next to fight the Germans. Italy? The Balkans? Greece and the Aegean? The war had to be fought somewhere: Allied planners estimated that a possible D-day in France was still a year away. The triumvirate of leaders—Roosevelt, Stalin, and Churchill—were at odds over where to fight next. The Russian victory at Stalingrad in February 1943, and the British triumph at El Alamein, had proved to be turning points. The preceding year in the Pacific, the Americans’ aircraft carrier groups had broken the invincibility of the Japanese navy at the Battle of Midway, only six months after Pearl Harbor.

Churchill argued that control of the Mediterranean meant control of Europe, and he wanted England, its armies, and the Royal Navy to have it. In the telegrams that the three leaders exchanged daily, early summer 1943 was devoted to deciding how the war in south and southeastern Europe would be fought. Control of Italy, with its 4,750 miles of coastline commanding every shipping lane in the middle of the Mediterranean, and thus access to the Suez Canal and India, was crucial for the British. It would also decide how military operations in neighboring countries in southern Europe, like Yugoslavia, Austria, and southern France, could be carried out. These in turn would dictate the postwar map of the northern Mediterranean.

A liberated Sicily and Italy would enable the Allies to dominate the Mediterranean sea-lanes and the air bases within striking distance of Germany and the whole of southern Europe. The Allies had three possible courses of action. First, invade Sicily and the Italian mainland, and fight from bottom to top, thus tying down hundreds of thousands of German troops who could otherwise be deployed against a forthcoming invasion of northwestern Europe, or else used in Russia. Second, they could stage seaborne landings at the very top of Italy, on the Mediterranean and Adriatic coasts, fight across the country, and cut off the whole mainland and the German and Italian forces in it. Third, they could negotiate an armistice and surrender with the Italians, move fast, and invade and occupy the country before the Germans had time to reinforce it from the north. Having occupied Italy, the Allies could then race up the spine of the country toward the Alps, outflanking and trapping German divisions by a series of leapfrogging amphibious landings on both Adriatic and Mediterranean coastlines. They chose the first option. And at first it all went according to plan.

Meeting at Casablanca in January 1943, the Americans and British argued about whether Sicily or Sardinia should be the first target. Sicily won. In Operation Husky, begun on the night of July 9, 1943, the British 8th Army under General Bernard Montgomery and the American 7th Army under Lieutenant General George S. Patton launched amphibious and airborne assaults across the southern and eastern coasts of Sicily. It was the largest venture of its kind in the war to date, and was successful, although many of the problems that could beset a combined amphibious, naval, and airborne operation did so. Husky was preceded by a series of diversions, the most imaginative of which was code-named “Operation Mincemeat.” The Allies were obviously desperate to persuade the Germans and Italians the landings were planned elsewhere, for as Winston Churchill had said after the success of the North Africa campaign, “Everyone but a bloody fool would know it’s Sicily next.”

So the Allies devised a cunning plan. The dead body of a homeless Welshman from north London was painstakingly disguised to resemble the corpse of a British Royal Marines officer. The scheme pretended that he had drowned after an air crash while carrying secret documents destined for General Harold Alexander, commander in chief of the Mediterranean theater. The body, with a fictitious identity—“Major Martin”—was dumped overboard by a British Royal Navy submarine off the southern coast of neutral Spain. A leather briefcase was chained to it, containing papers purporting to show that the Allies intended to invade Sardinia or Greece. A local fisherman found the body after it washed ashore, and it was passed to the Spanish navy, which in turn allowed German military intelligence in Madrid to copy the documents. Hitler fell for it. Field Marshal Erwin Rommel was transferred to Greece to command German operations there against the supposed Allied invasion and, most important, three German tank divisions were transferred from Russia and France to Greece, just before the strategically crucial armored battle at Kursk in the southern Ukraine in 1943.

But the actual invasion of Sicily, which began on the night of July 9, got off to a discouraging start. Because of strong winds and inexperienced pilots of the 147 gliders carrying the first wave of British airborne assault teams, only 12 reached their correct targets and 69 crashed into the sea. American paratroopers were scattered across southeastern Sicily. The initial landings were almost unopposed, but within hours the Germans and Italians counterattacked with tanks. The Italian army fought much harder than expected, and the British, overconfident after beating them in North Africa, found themselves out-fought by them, albeit briefly, on two occasions. But then the weather swung in the Allies’ favor: the Italians and Germans had assumed that nobody would attack in the bad weather that prevailed before the attack, and so they were slow to react. The enormous dominance in Allied air power hindered the German tanks’ ability to move easily in the open Sicilian countryside. Using their infantry and tanks together, the Allies—who were numerically outnumbered almost two to one—swung north, west, and east across Sicily, pushing the Germans into the northeastern corner toward the Strait of Messina. The Germans fought a series of bitter rearguard actions as they withdrew toward the port of Messina, from where they could rescue their troops back onto the toe of the mainland.

For the Allies, the fighting was characterized by several factors they would encounter on the mainland. The combat was dominated by the physical terrain and the Germans’ exemplary command of the fighting withdrawal. Both sides effectively deployed armor and infantry together: the Germans used lightning counterattacks to keep the Allies off guard as their main force withdrew from one defensive position to the next. It was to prove a precursor to the fighting on the mainland. There was also the heat, dust, mosquitoes, the lack of water, the beauty of the countryside, the two-thousand-year history, and the rural poverty.

The fighting in Sicily introduced the Allied soldiers and their commanders to a new German opponent, which was to dominate the strategic and operational dictats of their lives for the next eighteen months. Luftwaffe Feldmarschall Albert Kesselring was in charge of the German Army Command South. He was a fifty-eight-year-old veteran of the First World War who had commanded the German air forces during the invasion of Poland and France, and during Operation Barbarossa in Russia. He made several decisive observations in Sicily. Without German support, the Italians would collapse, although they were around 230,000 in number. So he decided to evacuate his 60,000 Germans back to the mainland and save them for the defense of southern Italy. He did this in a series of tactically brilliant fighting withdrawals, using the geography on land and sea to his advantage. More than 50,000 Germans escaped from Sicily by August, including two elite paratroop divisions, along with nearly 4,500 vehicles. Kesselring achieved this despite the fact that the Allies had command of land, sea, and air.

The campaign lasted four weeks. The British and Americans lost around 25,000 killed, wounded, missing, or captured, and the Germans some 20,000. The Italians surrendered and lost around 140,000, the majority of whom were taken prisoner. Fighting was brutal. But after a morning spent observing combat in a peach orchard, a British war artist said that he couldn’t decide which was more compelling: the physical beauty of the island or the visceral violence of infantry fighting. The combat casualties on the American side were exceeded only by the number of soldiers who caught malaria, from the Anopheles gambiae mosquito, breeding in the ponds, swamps, and drainage ditches that crisscrossed Sicily.

The Allies ran head-on into the world of Sicilian organized crime, and into la dolce vita too. In one key town, American troops fought alongside Italian Mafia gunmen masquerading as partisans, after their battalion commander agreed with the local capo that political and material control of the area would revert to him once the Germans had retreated. The geography was new too. Suddenly, after the throat-scorching heat and arid lack of compromise that were the sand and rocks of North Africa, here were the southern gardens of the old Roman Empire. The idiosyncratic color of war was also far from absent.

A unit of British special forces was the first to liberate the eastern port of Augusta. They outfought and outmaneuvered a numerically superior German unit, which withdrew toward a viaduct above the town. The British soldiers then liberated not just the bar in the local brothel but also the wardrobes of the prostitutes who worked in it. When an English company of soldiers arrived to link up with the Special Raiding Squadron, they found a small group of rugged, ragged men in special forces berets, captured German weapons slung over their shoulders, some wearing a mix of combat uniforms and women’s negligees and underwear. One was playing an upright piano under the orange trees in the town square, surrounded by the others, who were drinking Campari and singing.3

But then the Italians made a move that very nearly caught the Germans by surprise. In secret, they had negotiated an armistice with the British and Americans: it was signed on September 3 at a military base at Cassibile outside Syracuse in southern Sicily. Italy’s Fascist infrastructure, under the twenty-year dictatorship of Il Duce, Benito Mussolini, was by now on the ropes. The country, badly defeated in North Africa and at sea in the Mediterranean, was exhausted by war. Il Duce’s lavish architectural designs, feckless colonial wars, and huge public spending had bankrupted Italy. His cloying, sycophantic allegiance with Hitler had motivated him to dispatch 235,000 Italian troops of the 8th Army to fight alongside the Germans, Romanians, and Hungarians around Stalingrad. They were badly equipped, with weapons that, at best, semifunctioned in the Russian winter, and they had no suitable clothing for the subzero temperatures. In seven months, from August 1942 to February 1943, 88,000 were killed or went missing; 34,000 were wounded, many of them with extreme frostbite. And by July 1943, the Italian mainland was already being bombed by the Allies. The country’s predominantly Catholic population was at risk of reprisals if Pope Pius XII spoke out too vociferously about the Germans’ treatment of Europe’s Jews.

So the end, when it came, was draconian. Mussolini was told by the Grand Council of Fascism on July 25, 1943, that not only would his powers be curtailed, but control of the armed forces would be handed over to King Victor Emmanuel and Prime Minister Pietro Badoglio. The former was considered ineffectual; the latter, with a shameful record in World War I, was thought little better than Il Duce. So the next day Mussolini was arrested at Villa Savoia in Rome. The signature of the armistice was effectively a total capitulation of the country’s armed forces. For the Germans, who by chance had intercepted an Allied radio conversation from Sicily about the negotiations, it was a confirmation of what they had feared and expected all along. Their capricious and militarily lackluster allies had done a deal behind their backs.

Fearing that with the Italian army incapacitated, the British and Americans would quickly occupy Italy, the Germans moved as fast as they could and launched Operation Alarich, their plan to occupy Italy. If the Allies had been prepared to cooperate in full with the antifascist Italian resistance before Mussolini was deposed, the British landings in mainland Italy could have taken place unopposed. But British foreign secretary Anthony Eden insisted on a full and unconditional surrender by the Italians. During the 1935 Abyssinian crisis, Mussolini had described Eden, then an undersecretary of state at the Office of Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, as “the best dressed fool in Europe.” Eden remembered and smarted at this, and demanded a full and unconditional surrender.

Badoglio was timid and terrified of offending the Germans, so the chance to provide muscular military leadership to the many Italians who would be prepared to resist both Fascists and Germans was lost, and the Allies’ opportunity to join forces with the antifascist partisans was squandered. The Germans’ speedy reaction paid off: while the Allies were still negotiating final terms, and arguing about what should become of Italy’s monarchy, Hitler dispatched nine extra divisions down through the Brenner Pass, eastward from southern France and westward from Yugoslavia. After a short-lived defense by Italians loyal to the king, Rome was occupied by the Germans on September 9, 1943. The Italian army collapsed into three pieces.

Italy Falls Apart

As an Italian army officer, Arrigo Paladini had volunteered for service in Russia in 1941 and fought near Stalingrad. But unlike 88,000 other Italian soldiers in Russia who were killed or taken prisoner, Paladini made it home alive, with nothing worse than a bad case of frostbite in one foot. It meant that for the rest of his life he could hardly run. When the armistice was signed at Cassibile in September 1943, Arrigo Paladini was still a twenty-six-year-old second lieutenant in an artillery unit of the Italian army, based near Padua in northern Italy.

As soon as he heard news of the armistice, broadcast from Allied-occupied Algeria by the American major general Dwight Eisenhower, and then on the BBC and Radio Italy, Paladini quickly decided which side he was on. Fellow soldiers in the Italian army faced four choices: desert and go home; follow the orders of superior officers and face detention in squalid camps to await the eventual arrival of the Allies, or possible execution by the Germans; remain loyal to the deposed Mussolini and his Fascist regime; or join a partisan group. As a confirmed antifascist, he felt his only choice was to move south and enlist with a group operating in the Abruzzo region, which lies between the Apennines and the country’s eastern seaboard on the Adriatic.

Tens of thousands of former Italian soldiers, accompanied by civilians who hated the German occupation of their country, formed partisan groups. Loosely aligned along political lines, they were looking to the future while fighting in the present. The Germans were the immediate enemy, their defeat the immediate goal. But regional political control at the end of the war was the ultimate objective. Paladini’s group was allied to the Christian Democrats: its main rivals in the Abruzzo area were Communists. It started life at a meeting in an ilex grove above a village, and at the very beginning had around twenty men, with four Carcano rifles, two submachine guns, and a few Beretta pistols, captured from the police, among them. Paladini took the code name of “Eugene.”4

After being deposed, Mussolini had been put under the guard of a force of two hundred carabinieri, Italian paramilitary police officers who had remained loyal to the king. They hid the former dictator and his mistress, Clara Petacci, on the small Mediterranean island of La Maddalena, off Sardinia. After the Germans infiltrated an Italian-speaking agent onto the island, and then flew over it in a Heinkel He 111 taking aerial photographs, Mussolini was hurriedly moved.

They took him to the Hotel Campo Imperatore, a skiing resort in the Apennine mountains, high up on the plateau of the Gran Sasso and accessible only by cable car. Here he spent his time in his bedroom, eating in the deserted restaurant surrounded by carabinieri guards, and taking walks on the bare, deserted mountainside outside the hotel. Hitler, meanwhile, had been planning.

In September 1943, he ordered an Austrian colonel in the Waffen-SS, Otto Skorzeny, to come up with a plan to rescue Mussolini, and to assemble a group of men to do it. Thus was born Operation Eiche, or Oak. Skorzeny was colorful, charismatic, and austere, and one of Germany’s foremost practitioners of commando and antiguerrilla warfare. As a teenager growing up in Vienna in the 1920s depression, he once complained to his father that he had never tasted butter. Best get used to going without, replied his father. Skorzeny was a skilled fencer too, and one cheek bore the scar of a dueling schmiss, or blow from an opponent’s blade.5 By 1943 he was an officer in the Waffen-SS with a hard-earned reputation for success in counterinsurgency operations in France, Holland, the Balkans, and Russia. He commanded the newly formed SS commando unit Sonderverband Friedenthal, and with paratroopers from the German Luftwaffe, he rescued Mussolini without firing a shot.

The two hundred Italian carabinieri protecting Il Duce surrendered after Skorzeny and his assault team landed by glider on the top of the plateau next to the Imperatore. Mussolini, in a black homburg and overcoated against the autumnal Apennine chill, was flown to Rome—with a stop in Berlin to be greeted by Hitler—in a light aircraft. Then he returned to northern Italy, where he created the Italian Socialist Republic, a puppet Fascist state that the Germans drew out within the territory they occupied. It became known as the Salò Republic, from the northern Italian town in which it was headquartered. So with Mussolini now in his small Fascist statelet, Germany occupying Italy, and the Allies arriving on the mainland, Paladini and his small band got to work.

The Arguing Allies

By the time the Americans landed on the beaches at Salerno, south of Rome, in September 1943, the Allies had just lost one of their more capable generals. The irascible, direct, but tactically effective battlefield commander Lieutenant General George Patton had led the U.S. 7th Army in the invasion of Sicily. He had no time for soldiers under his command who complained of suffering from “battle fatigue,” or any form of neuropsychiatric combat-related stress. At the beginning of August 1943, visiting American military hospitals in Sicily, he assaulted and abused two soldiers who were claiming to be affected by fatigue. Army medical corpsmen had diagnosed at least one, if not both, of them to be in the early stages of malaria, alternating between high fever and shivering fits, with attendant paranoia, hallucinations, nausea, and vomiting. It is questionable that either of them knew what he was saying.6 Patton slapped both of them, kicked one in the behind, and threatened to shoot the other. News of the incident mushroomed, and despite there being as much support for Patton as criticism over the incident, he was sidelined from combat command for several months as the 7th Army was split up.7 His successor was a general who would influence the Allies’ strategy as much as Albert Kesselring, though in different ways.

Generals Mark Clark and Harold Alexander

Lieutenant General Mark Clark was a brave and ambitious staff commander who had risen fast through the ranks of the American officer corps. Born in 1896, his father was a career soldier in the U.S. Army; his mother, an army wife, was the daughter of Romanian Jews. He grew up on a series of army posts, joined the army in 1913 at age seventeen, and graduated from West Point in 1917 as a second lieutenant, 110th out of a class of 139. In the manner in which promotion often works in wartime, he was a captain five months later, before being wounded in France later that year fighting in the Vosges mountains. He remained in the military between the wars, holding a variety of staff appointments, at which he excelled, and was quickly promoted. By 1942, he was a major general and deputy commander in chief under Eisenhower in North Africa. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal by his friend and superior, General Eisenhower, after the successful completion of Operation Flagpole in October 1942.

The Allies were determined that the French army in Tunisia and Algeria not oppose the landings code-named “Operation Torch,” the invasion of North Africa. A group of pro-Allied senior officers from the pro-German Vichy French government, based in Tunisia, had indicated that they would be able to persuade the French forces in that country not to resist an Allied invasion. Along with a group of senior officers and three British commandos, Clark was sent to meet them. The group flew by B-17 Flying Fortress to Gibraltar and then boarded the British Royal Navy submarine HMS Seraph. (This vessel would later drop the fake body of “Major Martin” off the coast of southern Spain during Operation Mincemeat.) Clark spent three days ashore in Tunisia, the mission was a success, and senior French officers announced that when Allied troops came ashore in North Africa, they, the French, would arrange a cease-fire. Eisenhower was delighted. It showed Mark Clark’s diplomatic flexibility and powers of persuasion and command, and added to his staff capability. By November 1942, Clark was the youngest lieutenant general in the U.S. military.8

In January 1943, he took over command of America’s first field army of World War II—the 5th Army in Italy. Eisenhower was an admirer, and Clark was certainly brave in a mildly reckless way, but he had a reputation for being vainglorious and ambitious. Neither of these were unnatural or surprising qualities in a West Point cadet who had finished near the bottom of his class yet had risen so quickly in the military. Clark was also a classic product of the political economics of 1930s America, a country that was becoming a world superpower and where post-Depression industrial strength restored much of the people’s confidence. It was a country where merit, personal drive, and ambition went hand in hand. Clark was not lacking in of any of these, and he found that war and high command provided the fuse for this volatile trio of qualities.

The commander of the 15th Army Group, which contained the British 8th and American 5th Armies, was General Harold Alexander. The son of an earl, he was educated at Harrow, one of England’s leading private schools. He joined the Irish Guards in 1911, after briefly considering becoming an artist. Unlike so many of his generation, he survived the First World War, where he fought on the Somme, and was decorated for gallantry three times. Britain’s leading balladeer of Empire, Rudyard Kipling, arranged for his severely nearsighted son, John, to serve in Alexander’s battalion at the Battle of Loos in 1915, where he was killed. Afterward, he wrote that “it is undeniable that Colonel Alexander had the gift of handling the men on the lines to which they most readily responded … His subordinates loved him, even when he fell upon them blisteringly for their shortcomings; and his men were all his own.”9

Alexander served in India between the wars, and in 1937 was promoted to major general, the youngest in the British Army. After Dunkirk in 1940 and service in England, in 1942 he was dispatched to Burma to lead the army’s retreat to India. Recalled to the Western Desert by Churchill, he led the Allied advance across North Africa after the battle of El Alamein, and then took command of the 15th Army Group, reporting to Eisenhower. The British diplomat David Hunt, who served as an intelligence officer in North Africa, Italy, and Greece, was, after the war, on the British Committee of Historians of the Second World War. He considered Alexander the leading Allied general of the war.10 He quotes the American general Omar Bradley as saying that he was “the outstanding general’s general of the European war.” But despite this, he had an uneasy relationship with Mark Clark, who found him too reserved.

In September 1943, the main body of the two Allied armies landed at Salerno, south of Naples, on Operation Avalanche. Two other British landings took place in Calabria and at Taranto, on the toe and heel, respectively, of Italy. A deception operation code-named “Boardman” coincided with it, in which the British Special Operations Executive leaked faked plans to invade the Balkans via the Dalmatian Adriatic coast. The plan was successful, and these fell into the hands of the Germans in Yugoslavia. Winston Churchill was, in the words of an American staff officer, “obsessed with invading the Balkans,” part of his master plan to preempt a postwar Russian occupation of territory in southern Europe that Churchill saw as rightfully European, not Soviet.

Salerno was as far north as the Allies could land in Italy while still retaining fighter cover from Sicily. The advance bogged down. American troops that managed to break out of the Salerno bridgehead headed eastward instead of north; they tried to link up with American, British, Polish, Canadian, and Indian troops that were advancing northwest toward Rome from their landing grounds at the bottom of Italy. The linkup failed. The mountainous geography of the southern Apennines dictated that an advance to seize the main access routes into the outskirts Rome would have to cross three key rivers, then force its way up the valley of a fourth, the Liri, flowing from the mountains that lay to the south of the capital. Kesselring had anticipated this. The high ground that dominated these river crossings and the main roads were controlled by German artillery, antitank weapons, and infantry. Looming over the entrance to the Liri valley itself was a huge mountain, which had a large ancient Benedictine monastery on top of it. It was called Monte Cassino.

Trying to push northward and break the gridlock at Salerno, the Allies made a crucial strategic decision that turned into a tactical error. They carried out a huge amphibious landing north of Salerno, on the Mediterranean coast, at a small fishing port called Anzio. It was only thirty miles south of Rome. When 35,000 British and American troops landed there on January 10, 1944, they found themselves completely unopposed, and they took the Germans by surprise. They could have marched on the capital. But the querulous, disagreeing Allied generalship—“the Arguing Allies,” as they were known—came to the Germans’ rescue. Mark Clark placed the operation ashore under the command of an overhesitant American general. The British and Americans were then trapped for five months in an area where German gunners on the surrounding Alban Hills had every square mile mapped onto their fire plans. The fighting for both sides resembled the trench warfare of the Western Front, and one German officer described it as being worse than Stalingrad.

British General Harold Alexander’s 15th Army Group comprised Mark Clark’s 5th Army, with English General Oliver Leese commanding the 8th Army. The Allies’ command structure then took another blow: Montgomery had left for England in December 1943 to help lead the Allied invasion of Normandy. He left behind him what he saw as a situation of strategic and tactical disorganization, particularly by the Americans, that he was subsequently to describe as a “dog’s breakfast.”

Clark’s dislike of Alexander was compounded by his frustration at being the U.S. general who had to implement Alexander’s decision to bomb the monastery of Cassino—although Clark personally furiously disagreed with the order. The British in turn blamed Clark for the near failure of the landings at Salerno. Into this goulash of mutual dissatisfaction, they also stirred another ingredient. Clark had personally assigned the overcautious American major-general John Lucas to command the Anzio bridgehead, and the British, who took enormous casualties there, blamed Lucas for not breaking out of the isolated enclave.

The landing at Anzio had been designed to solve Salerno and the Cassino quagmire. It did neither. What it did do was give Field Marshal Albert Kesselring plenty of time to prepare successive defensive lines north of Rome, to which he could fall back one by one in a series of tactical withdrawals. It allowed him to reinforce the north of the country and establish a major defensive line that led diagonally across north-central Italy exactly where the Apeninne mountains and the Po River valley perfectly suited defensive warfare. It allowed him months to focus his capabilities and to build a string of mutually supporting positions all along this line, which led from the Adriatic coast on the east to the Mediterranean on the west. It was the strongest German defensive position in southern Europe. Kesselring called it Gotenstellung, the Gothic Line.

Italy was now a land of several opposing and cooperating forces. There were the Americans and British, with their multinational corps and divisions from India, Canada, and countries such as South Africa; there were the Germans; there were the Italian partisan groups, with their myriad political allegiances; and there were Italian Fascists loyal to Hitler and Mussolini. The list of protagonists in the fight for one of Western civilization’s oldest lands was as complex and tricky as the terrain and the history of Italy itself.