A Multinational Assault: Ten Armies on the Gothic Line

August 25, 1944

With seven experienced divisions pulled from their command, Lieutenant Generals Mark Clark and Oliver Leese had divided their forces into three. The British, Canadian, and Polish corps were to attack Rimini. The Americans, strengthened by Sidney Kirkman’s XIII Corps, were to strike toward Bologna. And on the Mediterranean coast, the multinational army of all the remaining Allied troops in Italy would push straight up the left flank, through the mountains overlooking it, to the key ports of La Spezia and then Genoa. Behind the lines, across the breadth of Italy, SOE and OSS agents would parachute with arms and supplies to lead the partisans in an enormous assault on the Germans from behind. The strategic aims were simple. To prevent Kesselring’s two German armies from escaping into France, Austria, or Yugoslavia by destroying them on the ground or taking their surrender. To exploit through the Apennines and Gothic Line defenses, flank left into the Po valley, and head toward Venice and Trieste, thence to Ljubljana and Vienna, reaching the latter before the Red Army. And finally, to help the different partisan groups save the Italian economic infrastructure—the dams, hydroelectric plants, factories—from destruction by the retreating Germans, so that Italy would have a functioning economy after the war ended.

In practice, the Italian economy meant northern Italy, so the Allied covert missions were concentrated in a long line westward from Liguria, Turin, via Milan to Venice. The large number of SOE and OSS detachments would also try, to the greatest extent possible, to oversee and channel the political aspirations of the different partisan groups. The Allies wanted to make sure that the postwar political apparatus was one of their choosing, was noncommunist, and stood a decent chance of contributing to postwar stability, rather than civil war.

The Attack in the West: The Nisei Head North

In the west, the U.S. 34th Infantry Division was tasked with holding the extreme end of the Allied line and fighting up toward La Spezia. Sergeant Daniel Inouye and the rest of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team were, by mid-August, recuperating after six weeks of constant advances, and four major battles, that had taken them as far as the Mediterranean where the Arno flows into the sea. They were preparing to head north to hit the Gothic Line where it meets the Mediterranean. The fighting had been tough: Inouye was quickly discovering the contradictions, fear, massive elation, successes, and simple tragic human sadness that are facts of life during wartime.

One morning he’d been on patrol in the Tuscan countryside, leading his squad in the sunshine along a gentle slope toward a farmhouse that seemed deserted. They got to about thirty yards from it when an MG-42 machine gun opened up from one of the windows. Inouye’s lead scout was cut almost in half by bullets. The Nisei hit the ground as the machine gun fired “steady, disciplined bursts of six” at them. They fired a bazooka rocket into the house, which detonated, and then charged, throwing hand grenades through the windows. They burst into the house and found two Germans torn to pieces by the bazooka. A third German was still alive, thrown back against the wall of the room semiconscious, one of his legs completely broken. Inouye approached, his finger on the trigger of his M1 Garand, which still had three rounds left in its magazine. The German muttered “kamerad” twice and smiled.1

Then the German reached inside his battle dress tunic. Was he going for a gun? Inouye hesitated. The Nisei sergeant had no time to make up his mind. He made a split-second decision and fired the last three .30-06 rounds from his rifle into the German soldier’s chest, the heavy bullets smacking him up against the wall. As the man slid sideways, dead, his hand fell out of his tunic. A photograph that he had been reaching for slipped from his fingers—a picture of an attractive woman and two small children. A handwritten inscription on it said “Deine dich liebende Frau, Heidi” (Your most loving wife, Heidi).

The incident caused Sergeant Daniel Inouye a massive crisis of conscience. Here he was, a respectable Japanese-American son from a household where any form of violence was abhorred. Where, as he said to the unit’s padre later, the family had an obligation to every sick cat and dog. He believed in the mantra “Thou shalt not kill.” But here was another Inouye, a capable, tough squad leader, proud to be a soldier. He felt there were two sides to him. The padre was succinct: “We are fighting because we have to—our enemy does believe in killing … You must fight—and yes, and kill—to protect the kind of life that helped you grow up to hate killing.”

Walking afterward in the darkness, Inouye reconciled himself, remembering his father’s plea not to bring dishonor on the family name. Feeling more resolved, he strode off into the dark back to his tent, utterly confident he knew which side honor was on.

Hardly had the crisis passed than he suddenly found himself medevaced to a hospital in Rome, as his unit prepared to move north to attack the Gothic Line. Under local anesthetic, he watched surgeons operate on him, and then was moved to a bed next to other American soldiers wounded in combat. They crowded around Inouye, staring at the swathes of bandages covering both his feet. They offered chocolate and cookies from the parcels they had received from home. Cigarettes were proffered. What, they asked, had happened to him? Bullet wounds? A land mine? The desperately embarrassed Japanese-American sergeant could hardly bear to reply. Two days before, in a defensive position after a patrol, he’d taken off his combat boots and been knocked back by the smell of infected flesh. A passing medic took one look, and within an hour he was on his way south to Rome, with two badly infected ingrown toenails. The moment he explained to the wounded combat veterans around him on the hospital ward what had happened, they took one look at him, said nothing, avoided eye contact, and didn’t speak to him again.

Two nights later, Daniel Inouye broke out of the hospital and went AWOL. He bribed the ward orderly with fifty dollars he had won playing dice, and spent two days and three nights hitching rides north, trying to avoid the military police. When he arrived back with Easy Company of the 2nd Battalion, his captain called him over and told him the hospital wanted to court-martial him. Then he hesitated and assured Inouye the unit would have a swift field trial, find him innocent, and he could accompany it northward. For the 442nd RCT was boarding Liberty ships in the port of Livorno. They’d gotten to the very edge of the Gothic Line positions, the first Allied troops to do so, but now were being pulled out of the line. Like so many of the other experienced Allied troops in Italy, they were being sent north to France. The Gothic Line would have to wait. To Inouye and his men, it seemed completely senseless.

The Buffalo Soldiers Arrive

The 442nd RCT was replaced by allies from three unexpected quarters: South Africans, a Brazilian Regimental Combat Team, and some fellow Americans who, like the Nisei, were no strangers to racial segregation. The U.S. 92nd Infantry Division arrived on the line that stretched along the River Arno. Nicknamed the “Buffalo Soldiers,” they were all black Americans, with a very small handful of white officers. Italian Fascist spies and German scouts from the SS units of the 16th Panzergrenadier Division, dug in opposite the U.S. 34th and the 92nd, reported back. Their opponents must have sounded like something from a National Socialist nightmare: half-breed Japanese, black Americans, a mix of white and black South Africans, and Brazilians.

Recruited mostly from the Deep South of the United States, some of the soldiers from the 92nd couldn’t read or write. The 370th Regimental Combat Team, commanded by Colonel Raymond G. Sherman, went abroad as the advance guard of the 92nd Infantry Division. This combat team was formed at Fort Huachuca in Arizona on April 4, 1944. During the period of intensive training for its movement overseas, men failing tests in the 370th were transferred out to other units and replaced by men with higher qualifications and capabilities. Many of these were volunteers. The whole combat team, consisting of the 370th Infantry, the 598th Field Artillery Battalion, and detachments from each of the special units of the 92nd Division, including the headquarters company, sailed from Hampton Roads, Virginia, on July 15, 1944. Transshipping at Oran in Algeria, it arrived at Naples on July 30.

The unit, secure in the knowledge that it was well trained, in excellent physical condition, and was made up of the 92nd Division’s best cross section of men, had high hopes and high morale. Its arrival in Italy produced flurries of excitement and anticipation among black service troops in the Mediterranean area equaled only by those produced by the arrival of the Tuskegee Airmen from the 99th Fighter Squadron and the 332nd Fighter Group. Like the Nisei, African-American troops had faced consistent opposition and prejudice since forming up as a unit in Fort Huachuca in Mississippi in 1941. But the Nisei faced discrimination not because of race per se, but because their race was that of their country’s enemy. The 92nd faced discrimination because they were black—out of pure racism. The American Red Cross collected racially segregated blood, as white and black troops were not then allowed to receive transfusions from each other. The 92nd Division was determined to prove its critics wrong.

One of their men who could read and write, and had a college education, was Ivan Houston, a six-foot-tall, nineteen-year-old athlete and boxer from Los Angeles, who’d majored in sports at the University of California. Houston’s father had served with another racially segregated division in the First World War. By the time World War II came around, the 92nd had been given the nickname the “Buffalo Soldiers,” after the description used by Native Americans for black soldiers in the U.S. Army in the 1870s. Houston became the clerk of D Company of the 366th Regiment shortly before they shipped out from Hampton Roads in Virginia. He had no idea where they were heading. They crossed the Atlantic and landed at the port of Oran in Algeria in July. Led by Lieutenant Colonel Clarence Doggett from Alabama, a white officer whom Houston and the other men respected, the 366th proceeded to the Bay of Naples at the end of July 1944. As they arrived, Houston and his colleagues reckoned they could only be en route to the front.

Many of the black troops came from dirt-poor backgrounds from rural Georgia, Mississippi, and Alabama, but none of them had ever seen such poverty as they witnessed in Naples in 1944. The harbor was full of ships that had been hit by air attacks and were half sunk; the port was full of dirty, hungry people, and as the African-American soldiers disembarked, ragged, grimy teenage boys ran along the line, trying to sell their sisters for soap. Naples was starving.

The Buffalo Soldiers trekked toward the front on foot and in trucks, moving northwest through countryside whose natural beauty had been removed by the savage fighting that had ground over it that year. Many trees had no leaves left, the branches stripped by artillery fire. Houston noticed little beauty on the route north, although he was taken aback by the random nature of environmental and human survival in wartime. Next to a clump of shattered trees, branches and trunks pitted with artillery shrapnel, leaves blown to dust, he saw some lemon trees standing untouched, their yellow fruit immaculate.

The 366th had made it to Tuscany, in front of the River Arno, by the last week of August. The area was teeming with different nationalities. Houston had grown up with Japanese Americans in California and felt at home with the 442nd RCT, which were very briefly next to them on the Arno Line. Like the Nisei, the men from the 92nd thought the idea of sending the Japanese-American unit to France, now that they were within touching distance of the Gothic Line, to be completely nonsensical. A Brazilian regimental combat team arrived behind the Buffalo Soldiers, the South Americans’ uniforms bearing the unit patch of a boa constrictor smoking a pipe. The men from the Brazilian Expeditionary Force spoke almost no English, but they seemed to dovetail culturally and linguistically with the Italians. The South Africans had also arrived, and Houston and his colleagues noticed instantly that every white South African officer had a black orderly. The Italians found the men from the 92nd fascinating and called them “the Good Giants.” They would call out “Tikedesi” to them, imitating their American accents, their way of saying “Take it easy.”

As the boiling-hot month of August started to wind to its end, and across the whole of Italy hundreds of thousands of men were hours away from going into action on the Gothic Line, the men of the 92nd kept themselves busy. They smoked, but as enlisted men they were not allowed to drink alcohol. Some GIs flicked their cigarette ash into their Coca-Cola bottles, hoping for a nicotine-induced high. The medics sipped their ethanol. From time to time there was captured German brandy and cognac, taken off prisoners, drunk out of sight of NCOs or officers. M1 Garands, M1 carbines, .45 Thompsons, .30 Browning machine guns, and Browning Automatic Rifles were cleaned again and again. The clock ticked down as the sun of summer burned on.

To the east of this racial melting pot on the Arno, the 1st Battalion of the Maratha Light Infantry had advanced into Florence and then refitted. As part of the 21st Infantry Brigade, itself part of 8th Indian Division, they were now under the command of the British XIII Corps that had been detached from the 8th Army to serve under General Mark Clark. Captain Eustace D’Souza and his men left their tented camp outside Florence in the third week of August, heading for a laying-up position just behind a new front line north of the city on the Gothic Line itself. The division moved twelve miles to the east, into the Pontassieve area. Here the River Sieve flows down in a great bend along the foothills of the Apennines. Within this bend the enemy held a series of high spurs that constituted the outworks of the Gothic Line, barring entry into the narrow valleys by which the main roads climb over the crests of the mountains. Due east of Florence, the first contours of this high ground are rounded and gracious, tree clad and heavily cultivated, but as the ridges fuse into the foothills, they tend to become sharp, rugged, and irregular. The Indian front covered the intermediate stage of this transformation, in which thickly wooded hills rose about thirteen hundred feet above the river, and in which the rolling countryside had begun to yield to narrow summits and little crooked valleys.

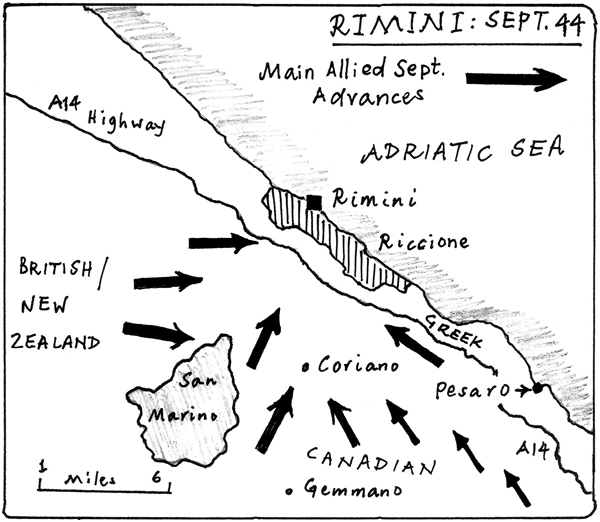

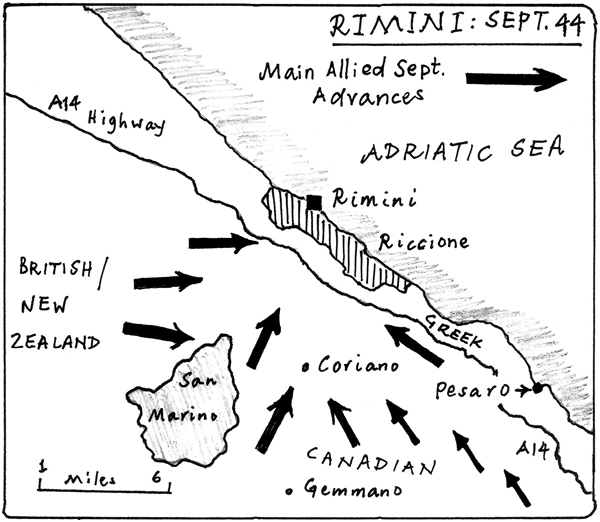

Meanwhile, to their right, the majority of the entire 8th Army had just been moved from the middle of Italy to the east. Kesselring was still convinced that the main Allied attack would come either in the center toward Bologna or in the west. An Allied deception plan, code-named “Operation Ulster,” had worked much better than expected: bombing raids on the outskirts of Bologna had helped persuade the Germans that the city was to be the focus of the Allies’ impending attack. The Germans had somehow missed the movement of eleven infantry divisions, with their accompanying artillery and engineer vehicles. Not to mention hundreds of tanks. It was late August in north-central Italy; the countryside was at its driest. Convoys of vehicles raised dust clouds that could be seen for miles. But somehow the telltale sound of ringing church bells—often used by Italian Fascist collaborators to signal the impending arrival of Allied troops—was absent. One reason was that the Germans had almost nonexistent aerial reconnaissance capability. Second, their forward troops were by now all dug in to their positions on the Gothic Line. Third, the troops took their lead from their commanding officers. Generaloberst Heinrich von Vietinghoff, commanding the 10th Army on the Adriatic front, and General Heidrich, the paratroop commander in Rimini, were absent. They were still on leave.

So when, at dawn on August 25, the first units of the British 8th Army crossed the Metauro River on Bailey bridges, and attacked German outposts east of Rimini under the cover of mortar and artillery fire, alarm bells did not ring. The Germans reported simply that the Allies were advancing to occupy ground vacated by withdrawing German soldiers. They also didn’t attach any significance to Indian units moving up from the south, or Polish cavalry units heading north from Pesaro. Lieutenant General Oliver Leese had won his Distinguished Service Order on the Somme leading his men in covert raids on German trenches; now, with a hundred thousand men, twenty-seven years later, he repeated this approach. In the opening hours of the attack on the Gothic Line, he had achieved complete surprise. From Rimini in the east, to Carrara in the west, the Allies moved forward under artillery and mortar barrages. In the far west, near the Mediterranean, Private 1st Class Ivan Houston said simply that “the whole front seemed to explode.”