Fighting German Artillery and Jim Crow: The Buffalo Soldiers in Tuscany

September–October 1944

Private Ivan Houston and the rest of the 370th Regimental Combat Team of the 92nd Infantry Division were the first black American army unit to go into action in World War II. So when they arrived near the 5th Army’s front line on the south banks of the Arno on August 24, senior officers, soldiers from other units, and war correspondents showed enormous interest in them. The Buffalo Soldiers had moved up to a thirty-five-mile-wide front extending east from the Mediterranean Sea, on the far west of the Allied front line. Given the number of veteran divisions that had been diverted to the fighting in southern France, American and British senior commanders were reportedly delighted to have the 92nd with them.

The 370th RCT formed part of the American 5th Army’s IV Corps, a seriously understrength formation that was desperately trying to patch together its numbers in time for the assault on the Gothic Line, which had already begun in the east. Antiaircraft units had been equipped with infantry weapons and formed into ad hoc rifle battalions. One Allied officer noted that they were “a polyglot task force of American and British anti-aircraft gunners acting as infantry, with Italian Partisans, Brazilians and coloured American troops fighting by their side and we learned that different peoples can fight well together.”

When the 370th first went into the line on the night of August 23, white officers accompanied them, intensely curious to see how this new unit would function under combat conditions. Would they bolt and run at the first enemy shot? Would they prove effortlessly determined and brave? Would they obey orders? How was America’s first black ground combat unit going to acquit itself? A U.S. Army one-star general, accompanied by a group of journalists and a camera crew, arrived to see them. Lieutenant General Mark Clark followed. Clark, who at Anzio had shown himself to be unafraid of frontline combat conditions, frequently visiting his men in their foxholes, was relieved to see the black soldiers. He used the occasion to indulge in a piece of histrionic grandstanding that drew attention to himself as a commander while at the same time endearing him enormously to his combat troops. It typified his personal and operational dichotomy. When he arrived to see the unit, a senior officer told Clark that one main problem the 370th were experiencing was that some of its more capable officers were being promoted too slowly.

“Give me an example,” the general is reported to have said. So the officer—a colonel—called over a black American first lieutenant who was an acting company commander, telling Clark that the officer was overdue for promotion. General Clark then turned to a captain who was accompanying his party, “borrowed” the officer’s twin bars of rank from his shoulders, and pinned them on the black lieutenant. News of the incident spread very fast among the men of the 92nd—as Clark intended—and was a huge boost for unit morale among the untried and untested division.1

Four days later, the 370th Regimental Combat Team’s spirits received another lift. It made its first “contact” with the enemy and came under fire. The headquarters of one of its three battalions was bombed in the night, the 598th Artillery that provided fire support for the 370th fired its first rounds at the enemy, and on August 30, a patrol of Buffalo Soldiers crossed the Arno. It destroyed a machine-gun post and captured two prisoners. The 370th RCT was operational. Then along with the rest of IV Corps, the unit crossed the wide, shallow waters of the Arno on September 1.

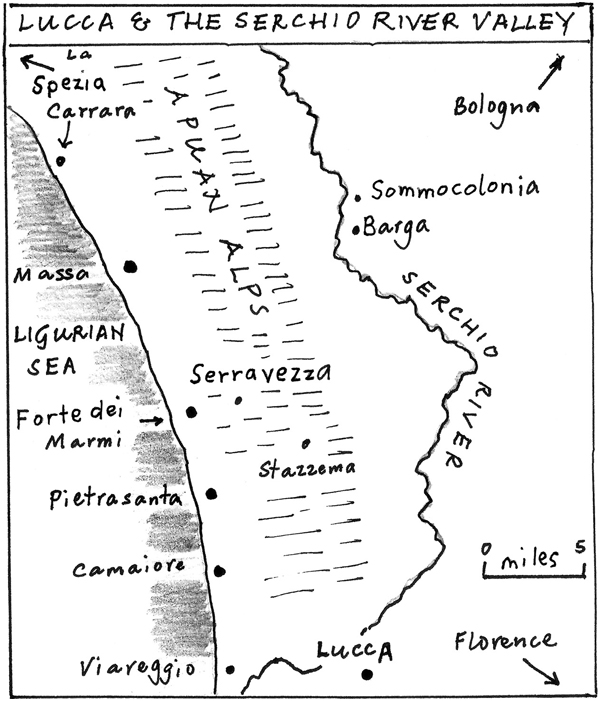

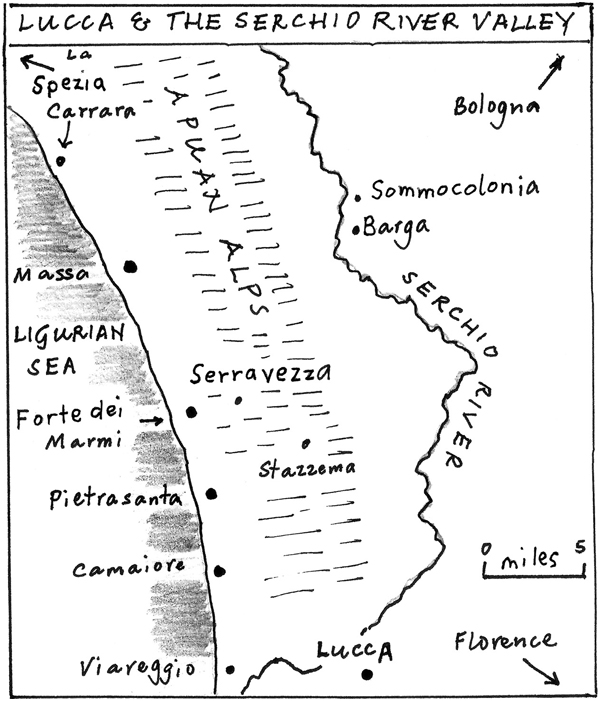

Six foot one, black, carrying the battalion’s maps, and of considerable interest to the Brazilians, the British, the white Americans, South Africans, and especially to the Italians around him, Private Ivan Houston waded the Arno along with his unit. The soldiers were briefed that in the enemy line opposite them were the panzergrenadiers of the 16th SS Division, as well as a composite unit of Germans from Alsace in eastern France, captured Poles, and Italian Fascist troops. Houston was less worried about which German troops he was going to come up against than about the constant artillery fire. His battalion headed north from the Arno toward the Tuscan town of Lucca. In between the Arno and this old walled city were two bits of high ground, Monte Pisano and Monte Albano, which IV Corps had been ordered to take, occupy, and hold, as they dominated all the high ground overlooking Lucca itself.

Houston and his battalion headquarters moved through four villages the other side of the river. In each of them, the welcome from Italian civilians was immense—old men, women, children, and people of all ages showered them with wine, kisses, grapes, and flowers. They held on to the soldiers’ vehicles, hugging the GIs, greeting them in Italian, some of the women crying, others kissing the Americans, others just watching and waving. Old men ran alongside the trucks and jeeps, pouring red wine from earthenware jugs. Children jumped up and down in the road. “Here were White Italians greeting Negro Americans as liberators and showering us with love, while in our own country we remained second-class citizens in all respects,” noted Houston in his diary.2

The American vehicles rumbled slowly through the four villages between the Arno and Monte Pisano. Outside one village, Houston had just given a tin of chopped ham and eggs from his K rations to a starving priest, thin, sunken of eye and gaunt of cheek, embarrassed to be asking for food. Suddenly he and his colleagues heard the loud muzzle report of an 88mm gun as it fired, followed by the hiss of the incoming shell. The soldiers jumped out of their truck and landed hard and fast in the prone position by the road as the 88mm shells exploded with heavy, air-displacing percussive whummpps. Houston and the other GIs had their faces in the dirt. Except for one of their number, a soldier who had been asleep in the truck when the 88 fired. Described by Houston as “a slow-moving, slow-talking Southern farm boy,” Private Hiram MacBeth remained in the truck, sound asleep through the bombardment.

As Houston realized for the first time that the enemy was actually trying to kill him, MacBeth slumbered on, waking only when they reached battalion headquarters. Houston paused in Pisa, which was still being fought over, and found himself taking cover at the bottom of the walls of the Leaning Tower. Next to him, keeping his head down, was a Nisei soldier. He and Houston had no time to reflect on how the two of them had ended up here in Italy fighting for America—raising your head four inches too far could get it shot off by a German sniper.

The German artillery kept coming in. From 88mm antiaircraft guns, 105mm field howitzers, self-propelled cannon, and even a pair of 150mm guns that the Germans had put on a spit of land outside La Spezia harbor, fifteen miles north. Every time a tank or jeep or truck moved, raising any form of dust, shells landed. Private Houston noted in the battalion log that between the 370th Battalion’s arrival on the line in August 1944 and the moment the war ended, there was not one whole day when they were not under some kind of artillery fire: in the advance to Lucca, he counted five hundred incoming rounds in one day. Taking cover in mid-September in a deserted Italian villa, he counted 127 shells landing in his vicinity. He could hear the boom of the German weapon firing the round, the roar as it traveled, and the hiss of its incoming trajectory. Houston’s father had served with an artillery unit of black American soldiers in World War I, and he had told his son the noise of shells passing overhead was like a freight train. Thirty years later it was exactly the same.

The unit’s regimental aid post was next to battalion headquarters where Private Houston was stationed. As his colleagues fought their way hand to hand into the village of Ripafratta, which lay between the Arno and Lucca, the young private saw the results of artillery fire firsthand. Medics bought in the body of the 370th’s executive officer, Major Aubrey Biggs, one of the unit’s white leaders and its first officer casualty. Houston saw from the blood-splashed mess of saw-edged cranial bone and the state of the man’s skull that he’d been killed by shrapnel. Two privates who were friends of Houston’s were then also hit: one died in the other’s arms, as he begged his friend to hang on until medical help arrived. The first man was then also hit by artillery. After four days in action, every single man in the unit had seen what the German artillery could do—Houston was with battalion headquarters in a deserted villa when two enormous shells fired by German howitzers from a range of ten miles landed in the building’s elegant dusty garden. Neither exploded, although they left enormous cone-shaped holes in the ground. Houston and his fellow soldiers stood around thinking how lucky they had been. Sometimes those wounded or killed by artillery bore almost no marks at all—the tiniest piece of shrapnel was enough to tear into a man’s body, and if it found an artery, vein, or major organ, it frequently proved lethal.

“Shrapnel” is the generic name given to the red-hot pieces of torn metal from the casing of a shell, ranging from a fifth the size of a little fingernail to great blooming flowers of molten metal the size of a man’s hand, edges curled and razor sharp. When the shell explodes, its casing tears apart, and the pieces of metal fly through the air almost at the speed of sound. It was named after Major General Henry Shrapnel, a British artillery officer and inventor who in 1784 invented a cannonball that was filled with lead shot, designed to blow up in midair. By 1803, the British Army had taken his design further and produced an elongated projectile, which they named the “Shrapnel shell.” His inventions were used by the British in wars against the Dutch, and then against Napoleon.

But sometimes the explosion of an artillery round did no damage at all. Ivan Houston and a colleague were taking cover behind a wall outside Lucca one day when an 88mm landed just the other side of it: there was an enormous explosion, the two men were thrown up into the air by the blast, but then, said Houston, they were dropped back down to earth very gently, completely unhurt.

The infantry of the 370th, which had taken to riding on the backs of the accompanying Sherman tanks of the 1st U.S. Armored Division, soon realized it was safer being on foot. Tanks attracted shells. Clinging to the backs of tanks as they went into action was a risky business, too: yes, it saved footslogging, but the perils of being swiped off by a revolving turret, burning yourself on the exhaust, and simply being thrown off, risking a broken limb on the lumpy, bumpy terrain were ever present.

Meanwhile, the Germans would post observers in any high building they could find, particularly the church in every town and village. They thought the Allies would not fire on them. They were also retreating from one piece of high ground to another, meaning they always had observers who could watch the American advance. By the end of the day on September 3, the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 370th had advanced over and marched around the high ground at Monte Pisano. The next stop was the medieval town of Lucca on the plain below.

The Fall of Lucca and the Advance to the Serchio River

The 370th Regimental Combat Team approached the town from the south and southwest. Behind them was the 100th Battalion of the Nisei, the last of the Japanese-American units still fighting on the line, before they were sent to France. Accompanying them were the Sherman tanks of the 1st Armored Division, and in reserve were the South Africans and the Brazilians. Houston, along with 3rd Battalion headquarters and K Company, moved toward the small hamlet of Cerasomma, which lies on the railway that leads due west from Lucca to the sea. Where the track crosses the road from Viareggio to Lucca, there was a large old house, built in the eighteenth century, surrounded by gardens of magnolia, palm, and pine trees. A tiled balcony looks out on the gardens at the back, while in front a colonnade of pillars provides shade over a terrace and patio. Villa Orsini is Tuscan Risorgimento architecture at its most elegant.

Battalion HQ of the 3rd/370th moved in and made it their temporary home. Outside the front door, the road leads right across the level crossing down to Viareggio, and left to Lucca. The regimental commander, Colonel Clarence W. Daugette Jr., and his 2 i/c were en route to the villa when another artillery barrage caught them and the headquarters party in the open—they were pinned down for six hours before they could move into the new HQ at Villa Orsini as dark fell. Compiling the casualty list for the battalion that night, the officers saw that 6 men had been killed and at least 30 had been wounded. These included a disproportionately high number of junior officers and senior noncommissioned officers, the soldiers who were always at the front leading and encouraging their men. The operational spine of the 370th was made up of these men: they had been the first into training at Fort Huachuca, the best qualified on command and skills courses, and were the soldiers the junior ranks looked up to and, now, in their first month of combat, were following into battle.

Houston knew the 370th RCT was good—its soldiers were well trained, but the junior leadership of the division was being wounded or killed very quickly, and the officers and NCOs were lasting only a matter of days. It was, he noted, “devastating.” Sufficient replacements weren’t available, as the number of soldiers from the 92nd who had scored sufficiently well on the Army General Classification Test was low, and so all the best men had been sent with the 370th to the front line first. The reserves were not of the same standard as the men from the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Battalions now surrounding Lucca, and the regiment’s officers were desperately concerned about how this was going to affect the 92nd’s performance in battle on the Gothic Line, at a time when the black American soldiers were under the scrutiny of everybody in the 5th Army. They were the first black combat infantry unit deployed in World War II, made up of men who had been systematically discriminated against, as had their families and relatives, for three centuries. They had arrived in an important theater of operations at a time when the U.S. Army needed every man it could get, and the 370th RCT had been posted to a stretch of the line that was as vital, and well defended, as any other. The men of the 370th knew they had a lot to prove, and their officers, both black and white, and senior and junior NCOs were determined that the unit give as good an account of itself as possible. It was not just German artillery the men were up against. Their military performance was being evaluated on their training and combat conduct, as well as through a prism comprised of expectations based upon race. But when it came to it, they were a combat unit as capable as any other, they had received the same training in the same places with the same equipment, and now in Italy they were facing the same obstacles and enemy as other Allied soldiers. Combat, the Germans, and the Gothic Line were not interested in ethnicity, race, or creed: it was universal soldiering skills that counted.

The unit had expected to have to fight hand to hand for the walled city of Lucca, a Roman and medieval city with stone and earth walls thirty feet high surrounding it on all sides. There were four gates, which one entered through stone arches. Outside the walls was a clear area of flat grass that stretched more than a hundred yards on all sides. The town had been built to be defended. From the top of its walls, machine guns and infantrymen would have made short work of any attackers. The 370th had requested flamethrowers as additional support for their attack. But when the combat companies of the 3rd Battalion moved east along the road from Villa Orsini and moved in from the south of the town, they found the city deserted. The Germans had pulled back to the far side of the Serchio River, into the Apennines, the heart of the Gothic Line.

On the morning of September 10, two things were immediately noticeable to every man in the 370th Regimental Combat Team who stood in the late autumn sun looking up at the Apennine mountains. First, the incessant German artillery that had marked every hour of their time on the line since late August had stopped. The explosive punctuations that had disrupted every minute of every hour for the men suddenly ceased. The second was that the mountains were going to prove formidable obstacles to attack.

To the north of Lucca, the Apennine range of Tuscany begins. Between fifteen hundred and six thousand feet high, the mountains rise steeply upward from the coastal plain along the Mediterranean. In the first valley that runs parallel to the coast, where the mountains start, is the Serchio River. It flows down from the mountains absolutely in parallel with the seaside, about fifteen miles inland. Mountains rise up on both sides of it, and the Germans had made these the backbone of their most westerly Gothic Line defenses. For attacking troops, it was pointless trying to capture and hold the cities and towns on the Mediterranean coast—Carrara, La Spezia—if they couldn’t take and hold the mountains that overlooked them, from which artillery and mortar fire could be hurled at will down onto the plain that ran along the sea. And the only way to take the mountain peaks was to take the road that snaked north through the Serchio valley at their base. As well as the towns and villages that lay on this road. The Germans had established defensive positions all the way along its length, and as they withdrew northward, they were demolishing bridges, blowing up the narrow roads, dynamiting rock faces to cause landslides, and leaving behind barbed wire, booby traps, and land mines. The 370th Regimental Combat team, backed up by the Brazilians, the 1st Armored Division, some attached British units, and the South Africans, were given the mission of taking the valley and the key mountains that rose above it. In the west of Italy, it was the best-defended stretch of the Gothic Line before it ran into the Mediterranean Sea.

At the last moment, the Buffalo Soldiers suddenly discovered they were going to attack it without the support of the tanks that had accompanied them all the way north from the Arno. Far to the east, parts of the U.S. 5th Army had broken through Il Giogo Pass on September 18, a crucial mountain bottleneck on the Gothic Line south of Bologna. The Shermans of the 1st Armored were told to prepare to move toward the center of the Allied line in support.

The Serchio River rushed heavy and high past the men of the 370th a week later as they made a nighttime advance up the only stretch of road in the valley the Germans hadn’t destroyed. Their target was a hill their HQ had code-named “Mexico.” that rose above them. It had a heavy stone castle on top, was defended by artillery, mortars, and machine guns, and seemed to be impregnable to the artillery fire that the Buffalo Soldiers had been laying onto it all day. An attack by three companies, supported by artillery and engineers, went in, the black American soldiers climbing, scrambling, walking, running, and in some places crawling up its steep slopes. The officers in the 5th Army who wanted to see how the Buffalo Soldiers fought should have been there that day, noted several of its officers and NCOs. At one point the Germans were bringing artillery to bear almost on their own dugouts on the top of the hill, so close were the men of the 370th. But three repeated attacks over thirty-six hours failed to dislodge the Germans, who were heavily and cleverly dug in. Still, the Buffalo Soldiers were not giving up: there were more than fifty wounded piling up in the regimental aid post. Private Houston was at the battalion HQ and led two casualties off the hill. One had shot off his own thumb so he could be medevaced out of the line. But he was an exception.

On the summit of Mexico, Sergeant Charles “Schoolboy” Patterson from Fort Wayne, Indiana, led the charge. He destroyed three MG-42 positions with hand grenades, but the incoming fire from five other machine-gun nests farther up the summit—which had pinned down a whole company of the 3rd Battalion—prevented him from moving forward. He was to be awarded the Silver Star for bravery in pressing home the attack. But Mexico proved to be an objective that the men couldn’t take, so instead of wasting more soldiers, the commander of the 1st Armored Division ordered the men off the slopes and posted them on surrounding high ground with mortars and heavy machine guns. These kept up a constant stream of fire on the Germans dug in on Mexico, who were now surrounded. Four companies from the 370th had taken two dozen dead and fifty injured in three separate attacks, by night and day, that had lasted forty-eight hours. The Germans pulled out a week later. The soldiers of the 370th had now proved themselves in combat, but they had taken very significant losses of very significant men—their junior officers and NCOs.

They had advanced into the Gothic Line and cut the key Highway 12 that ran east–west between Tuscany and the coast. They were now embedded deep within the Serchio valley, up against the German defensive positions. They had to take and break these to be able to clear the mountains above the valley, which would in turn allow them to clear the coast, which ran parallel to them the other side of the mountain range. In the far east of Italy, the fighting around Rimini and in the Po valley for cities like Ravenna was to decide the fate of the Adriatic end of the Gothic Line. Bologna would decide the middle. But in the west, the winner or loser would be the side that won the Serchio valley and the mountains that rose on both sides above it.