Regular and Irregular Forces: The Fall of Ravenna

November 1944

The weather in northern Italy had truly broken by November 1944. For the men who had fought in the south of the country, it was like being back in the valleys around Monte Cassino. Already-soaked boots got wetter every time they were put into a river or stream or water-logged field. Feet and boots never properly dried. Every day seemed to be a symphony of damp uniforms, rain, mud, physical effort, violence, cold food, and relentless discomfort. Jaundice hit the infantry particularly badly, and although the Allied troops were emerging out of the seemingly endless rows of Apennine ridges and mountains into the plains of Lombardy, conditions did not seem to improve. As one Canadian officer wrote, “There always seemed to be one more battle we were being asked to fight.”1 In October, the Canadians had fought a wet, arduous, morale-sapping battle for the Savio River west of Rimini; many of the officers believed it had been an unnecessary fight. That the river was or was not strategically and tactically important was not the main divisive issue. The river could have been outflanked, as it sat in empty countryside. What mattered to the Canadians was morale. The cold, the wet, the mud, the ceaseless slog of infantry attacks across rivers the Germans defended easily and with tactical élan made them feel that although they had advanced hundreds of miles geographically since the preceding year, here they were, still fighting, with no end in sight. The idiosyncratic and independent-minded Canadian generalship was arguing among itself again. Self-inflicted wounds, absence without leave, and desertion had become major problems, and the Canadians, normally stoic and resilient, were hit as hard as any Allied unit.

An officer from 1st Infantry Division noted that the attacks in October had been distinguished by the lack of time the Canadians had to prepare for them, the “useless or impossible” nature of the objectives and plans, and not enough men. A company commander from Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry said that the “poor morale was due to the belief that the war would be over soon, the recollection of last winter’s misery, the belief that the Gothic Line battles were supposed to be the last show for Canadian infantrymen in Italy and general war weariness, especially in Italy.” The major added that “at the present time all brigades are busily occupied with Courts Martial, chiefly desertion and Absence Without Leave charges.”2

Available manpower was still being diverted in two directions where the strategic requirements had higher priority—northwest Europe and the Far East. In both theaters it was very obvious by November 1944 that the war was not, once again, going to be over by Christmas. In northwest Europe, the British, Americans, and Canadians were bogged down in eastern Holland and just inside the German border. For the Allied troops north of Rimini, this meant more battles and another wet, cold, snowy winter in Italy. Both Eisenhower, as supreme allied commander, and Field Marshal Alexander, as commander of troops in the Mediterranean, now had yet another priority in southeastern Europe.

First, they had to continue breaking through the Gothic Line, despite the onset of autumn and winter weather. Then they had to contain Field Marshal Kesselring’s troops in Italy, and use the Italian partisans to their best strategic advantage, without letting them dissolve into internecine, strategically useless struggles with the Germans and each other as had happened over the self-declared Republic of Domodossola. In early November, Harold Alexander’s orders made clear that they required 5th and 8th Armies to “maintain maximum pressure … in early December” when Eisenhower was hoping to launch a major offensive in northwest Europe. This offensive was forever being delayed or postponed. Alexander and Churchill were frustrated at what they increasingly saw as a military “housekeeping” role now that they had just begun to break the Gothic Line: they still insisted their strategic priorities in the Mediterranean remained Italy and the Balkans. Break the Gothic Line, they said, take Genoa, Milan, Turin, and Venice, advance on Trieste, and then head for Vienna, via the Brenner Pass and the Ljubljana Gap. It was no longer a matter of just containing Kesselring’s forces in Italy and preventing them escaping into Austria and Yugoslavia; it was a very real need to prevent Marshal Tito’s partisans and the Red Army that followed them from advancing beyond Trieste. So suddenly, by November, the cities on the Adriatic coast of Italy took on as much strategic importance as Milan and Genoa.

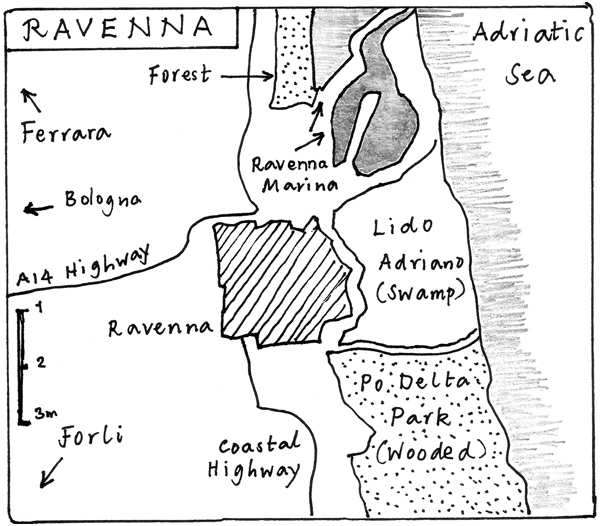

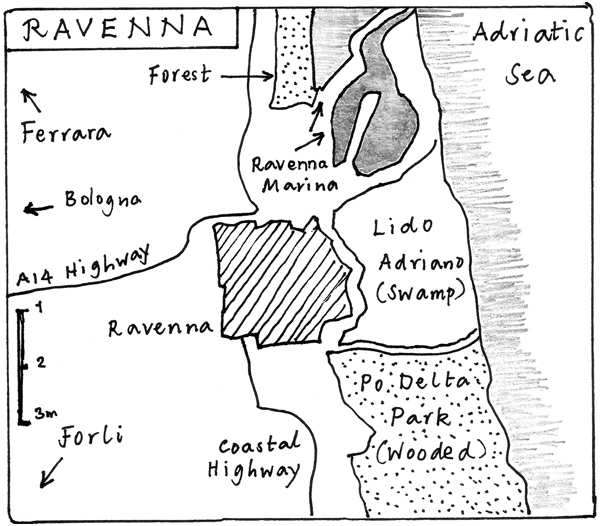

The city of Ravenna sits on the Adriatic coast north of Rimini, two miles inland. Two rivers flow through the town, and where they run into the sea there are large sandy beaches and salt flats. To the north and south are wide marshy areas of saltwater lagoons and low pine forests, where swampy water is crisscrossed by muddy stretches covered in reeds. The three main roads that trisect the city head west to Forli and Bologna, northwest to Ferrara, and due north along the coast toward Lake Comacchio and Venice. On November 9, the Indians took the town of Forli, the first major objective on the flank of the Apennines facing the Po. The mountains stretch in a direct southeast–northwest diagonal line across the top of Italy from Rimini to Forli to Bologna and eventually to Milan. They form a barrier in the west with the mountainous terrain of central Italy; in the east, they are the last border before the water-drenched plains of Lombardy, the Po valley. To avoid encirclement, the Germans had retreated in three directions: west to Bologna, north toward Ferrara and the Alps, and east to Ravenna. The 8th Army would be in charge of taking the latter.

The main partisan group in and around the city was the 28th Garibaldi Brigade. Unlike some of the other advancing Allied troops, their morale was sky-high. It was simple: liberation from the Germans was imminent. Mino Farneti, the young partisan who had captured the German plans for the Gothic Line from the motorcycle dispatch rider outside Rimini, was part of this group. In mid-November, the Allies parachuted arms and equipment to him and his men. Their main commander was Arrigo Boldrini, nicknamed “Bulow.”3 He had devised a clever plan whereby the partisans, along with Allied armored and infantry units supported by special forces, could capture the city. Ravenna was defended by three German divisions whose forces were deployed in a 360-degree defense. Bulow knew that the Allies desperately needed to take the city—but without destroying much of its art and architecture. He sent a radio message to the Allies, via the OSS, that his plan could help achieve this objective, but that he needed to meet with the Canadian and British commanders in person. He and his men were all Communist supporters, so Boldrini knew the importance of persuading the strongly anticommunist British that the 28th Garibaldi Brigade was a reliable asset.

The Canadians were based at Cervia, a town ten miles south of Ravenna on the coast. The Allies radioed back that they would send a submarine to pick up Arrigo Boldrini, but too impatient to wait for it and preferring to do things his own way, he set off by fishing boat. There were twelve Italian fishermen at the oars, and Bulow was also bringing with him two American air force pilots who had escaped from the Germans. Along with “a few pistols and a large keg of wine,” the group set off down the coast.4 It was a moonlit night and the boat managed to reach Cervia without being spotted by the Germans. An OSS colonel was there to meet them. The American took the group straight to Allied headquarters, where Bulow explained to the new commanding officer of the 8th Army, the English lieutenant general Richard McCreery, how he thought Ravenna could be taken.

The partisans from the Garibaldi Brigade would attack from the north and west; Allied infantry and tanks would come in from the south, up the main axis road from Cervia and Rimini; other partisan groups would ambush the Germans’ escape route northwest to Ferrara; an unorthodox formation of Allied commandos would storm into the city from the eastern seacoast. The Germans had opened the dikes on some of the waterways surrounding the city so that the main coastal road, Highway 16, was flooded in some places. Much of the land around Ravenna was underwater. But McCreery gave the plan the thumbs-up. Bulow went back to Ravenna with an 8th Army liaison officer.

McCreery’s plan followed Bulow’s. A composite force of tanks, infantry, engineers, artillery, and amphibious vehicle handlers would make up the main strike element. A British colonel named Andrew Horsbrugh-Porter from the 27th Lancers would command. His force, 2,000 men strong, was immediately dubbed “Porterforce.” The cavalry colonel was an aristocratic Englishman who liked polo, had been wounded and decorated in the evacuation from Dunkirk in 1940, and had a keen understanding of irregular warfare. To aid his men and the partisans, he enlisted the help of one of the most unorthodox Allied fighting units of the war.

Popski’s Private Army

Popski’s Private Army was the unofficial name of Number 1 Demolition Squadron, a unit of British special forces set up in Cairo in 1942. It had operated with the Special Air Service and the Long Range Desert Group in North Africa, and had arrived in Italy in September 1943 at Taranto. They deployed in heavily armed Willys Jeeps, divided into “fighting patrols” of six vehicles with three men in each. They had ample firepower, and the jeeps were mounted with .50 caliber and .30 caliber Browning belt-fed machine guns. Like the Special Air Service and the Long Range Desert Group, Number 1 Demolition Squadron recruited men from across the services, eschewed formalities of rank and parade-ground discipline, and operated as a cohesive small raiding squadron of special forces. By the winter of 1944, it included a wildly eclectic mixture of fighters—British, Europeans, Russians, and Italians who had been German POWs, as well as Italian partisans. The Canadian Westminster Regiment, no slouch itself in terms of individualistic soldiering, thought them the most glamorous unit operating in the 8th Army. If the Westminsters’ snipers sported unorthodox uniforms and weapons, the men from Popski’s Private Army carried everything they found that suited their purpose: not just .45 Thompsons and German Schmeissers, but also Italian MP 38 Berettas, American Garands, Lugers, and Colt .45 M1911 semiautomatic pistols. They had fought with Arrigo Boldrini’s partisans before and knew the terrain around Ravenna. They were also experienced in landing an armed jeep from the amphibious vehicle known as DUKW (pronounced “duck”), or from landing craft.

Their commanding officer was as unorthodox as his unit. Major Vladimir Peniakoff was a forty-seven-year-old Belgian Russian who had been educated at Cambridge and served in the First World War as an artillery gunner, where he spent a year in the hospital. Qualifying as an engineer after the war, he managed a sugar refinery in Egypt, learned Arabic, spent time climbing in the Italian Alps and exploring in the Middle East, and became a member of the Royal Geographical Society. He formed the Libyan Arab Force Commando in the Western Desert in 1941, and was awarded the Military Cross while raiding behind enemy lines with them and with the Long Range Desert Group. His nickname, and that of his guerilla force, was a sub-derivation of his name—nobody on the radio net could pronounce Peniakoff, so he and his guerrilla force were called “Popski.” He formed his raiding squadron with two other officers who had all been in the LAFC with him—Captain Robert Park Yunnie and Major Jean Caneri.5

Porterforce was made up of the British 27th Lancers and King’s Dragoon Guards, both based on Dingo, Ferret, and Scout armored cars. The tanks of the Royal Canadian Dragoons and the Princess Louise Dragoon Guards backed them up. Popski’s Private Army did the reconnaissance, while component parts of no fewer than five artillery regiments provided fire support, and three antitank regiments assured some protection against Germans tanks. Fourteen different British and Canadian units handled medical care, bridge building, engineering, military police, signaling, and vehicle maintenance. They had three infantry battalions attached to them, one from the British Essex Regiment, one from the Royal Air Force Regiment, and the Canadian Westminsters from British Columbia. “In these improvised forces there was a return to the delightful informality and lack of spit-and-polish that characterized the Eighth Army’s activities in its palmiest days in North Africa.”6

In no other single action in the Italian campaign had such a selection of units gathered on one target. In Ravenna itself was the German 114th Jäger Division. The Westminsters had advanced slowly toward the city, across what seemed to them an endless variety of ditches, streams, rivulets, rivers, flooded fields, and canals. At every point behind them, the Germans had left mines and booby traps, each of which required personal clearance. “Anyone who maintains that the Germans are an unimaginative race, tied to routine, obviously has never encountered those responsible for the mine-laying efforts on the Italian front,” noted the Westminsters’ diary.

The Attack on Ravenna

Given the ironic and inappropriate name “Operation Chuckle,” the Allied and partisan assault on the city began on November 29. On the evening of that day, Arrigo Boldrini split his 1,500 men into two groups of about 650 and 850. He then started to move them toward the outskirts of the city along paths and roads that the men knew by heart—most of them being from Ravenna. One partisan said that his mother had given him an extra helping of eels and polenta to keep him going throughout the night. An OSS document noted that along these routes the peasants had locked up their dogs and kept their doors unlocked in case the partisans needed to take cover quickly from the Germans. Bulow’s smaller group of 650 partisans took position in a valley north of Ravenna, while the 850 deployed near one of the rivers that cut south of the town. A weapons drop from the OSS landed on December 2, as the men waited for the Allies to get into position. On December 3, the OSS sent Bulow a simple message over the radio: “Attack. Good luck!”

At three o’clock in the morning on December 4, 823 partisans of the 28th Garibaldi Brigade armed with one 47mm antitank gun, four mortars, and a dozen heavy machine guns set off along sandy footpaths to their start line positions to attack 2,500 Germans holed up in concrete bunkers, protected by tanks and artillery, guarding the seaward entry to the city.7 The attack took two hours and the Germans surrendered with hardly a fight. Simultaneously, Bulow’s partisans attacked pillboxes, roadblocks, machine-gun positions, and German unit headquarters set up in farmhouses and, in one case, a lockkeeper’s cottage. Believing themselves surrounded, almost all the Germans surrendered, but not before they had transmitted the emergency radio signal burst to their colleagues that warned them they were being attacked. The fighting went on all night. At 5:30 A.M, Bulow’s men took the enemy by surprise again. All across the area north of Ravenna, various partisan units went after different German strongholds, many of which surrendered after finding themselves surrounded.

Popski’s Private Army had a four-mile-long section of the eastern flank, including the main Highway 16, which led from Ravenna to Rimini, and the seaboard approaches to the city. There were a sandy beach, dunes, low, stunted pine and oak trees hit by the maritime wind, while inland the Germans had flooded the marshland, salt flats, and fields: three straight canals flowed directly through them. The Germans had 75mm antitank, mortar, and machine-gun positions in all of their favorite locations, tried and trusted from one end of Italy to the other: in haystacks, on riverbanks, dug into embankments, in the upper and lower floors of farmhouses, and in stands of trees. The very open country gave them extremely clear fields of fire.

Popski’s Private Army came ashore from small landing craft and from the amphibious, two-and-a-half-ton, six-wheeled DUKWs. These carried Willys Jeeps up to the beaches, and they then drove off. The commandos spread out in their different fighting patrols to their different objectives. The first was the defended hamlet of Fosso di Ghiaia, which lay on the coast road into Ravenna, at the edge of one of the flooded areas of marshland bordering the coast. In the early-morning mist on December 4, ten jeeps drove up to the edge of the village and opened fire with their .30 and .50 Browning heavy machine guns. The defenders surrendered, as they did in five other positions.

The Germans had also established a strong position in one of the medieval watch towers that sat on the coast at the mouth of one of the rivers. Italian partisans from Arrigo Boldrini’s brigade led the observation mission, and when they were sure of the movements of the Germans based inside, they sent a radio signal to the OSS in Cernia, which passed it to Popski’s commandos. Fifteen of them landed on the beach and hid in a barn forty yards from the tower.8

At half past eight in the morning, the Germans called everybody for breakfast: five minutes later, three partisans and three commandos walked through the door, and the Germans surrendered. The captives were taken away. At midday, the same process happened again. And in the evening. By nightfall, the Germans were sufficiently worried by these mysterious disappearances that they pulled all of their forces south of the river back to the center of the city. The Germans lost an estimated 40 killed and about 150 prisoners. The commandos: 3 dead and 5 wounded.

The German 114th Division tried to move its armored cars and tanks out of the center of Ravenna to confront the Canadians south of the city, but fast movement in the tight, enclosed streets—now suddenly full of partisans—was next to impossible. Popski’s commandos held the bridges over the main river and two canals south of town, and when the Westminsters and Canadian 12th Royal Lancers arrived, with one of Bulow’s partisan units leading them, the Germans realized they were trapped, and they decided to withdraw and retreat northwest toward Ferrara. But 650 partisans were waiting alongside the beginning of the road they took, and a Canadian tank regiment was accelerating fast around the city to cut them off. At 4:30 on the afternoon of December 5, the OSS radio was able to send a succinct message: “British in Ravenna. Regards to all.”

The Canadians took 171 prisoners, and lost 30 casualties. Arrigo Boldrini asked the 8th Army headquarters for formal permission to attach a unit of 800 of his men—and women—to the official British battle roster. Lieutenant General Richard McCreery, delighted at the success of the operation to liberate Ravenna, and the almost nonexistent damage to the city, said yes immediately. The 8th Army now had an official Communist partisan unit in its ranks. And then McCreery went one better. He gave a victory parade in Ravenna’s main square, in the shadow of the monumental statue of Garibaldi. Here Arrigo Boldrini was presented with Italy’s Medaglio d’Oro for bravery in liberating his city. A large parade of his partisans observed the occasion. The British war artist Edward Bawden climbed to the top of a municipal building overlooking the piazza to draw the parade for the Imperial War Museum in London. He described the scene to his wife: “Most of the square was clasped in shadow, only a few houses at one end and Garibaldi raised high on a pedestal caught the light, and his figure in white stone dominated the scene. For the occasion … a standard uniform was issued [to the partisans]: khaki pants, peagreen battledress blouse & cow pat cap. The red scarf around the neck links memories of Garibaldi to more recent ones of the hammer & sickle.”9

Lieutenant General McCreery was from the same generation, the same war, and the same background as Oliver Leese, but he was a different man and a completely different general. His father was an American Olympic polo champion, and his Scottish mother a descendant of John McAdam, who invented tarmac. McCreery inherited the dash of the former and the doughty persistence and reliability of the latter. Like almost all of the senior generals in Italy, he had served in the First World War. Only seventeen when he joined up, he was awarded the Military Cross in 1918 and went on to higher command. He was a cavalryman from the 12th Royal Lancers, and loved horses and riding. Despite having lost several toes on the Western Front and having a hole in his right leg, he won prizes for equestrianism between the wars and by 1939 was a brigadier. He served at Dunkirk and as a chief of staff at El Alamein, taking over X Corps on its arrival in Italy in 1943. He was knighted in the same field in Italy by King George VI—traveling as “General Collingwood”—that saw not only Oliver Leese knighted but also Major Jack Mahony receive the Victoria Cross. His style was completely different from Leese’s: McCreery thought Montgomery too cautious and hesitant, and he knew that in the fast-moving battles in northern Italy that were going to follow the fall of Ravenna, the dash and buccaneering spirit of the polo field were going to be needed. Before Ravenna, the Germans had either made sharp tactical withdrawals before battles were lost—as at Rimini, the Strait of Messina, and in Rome—or held the Allies on their own defensive terms, as in the Serchio valley and at Monte Cassino. Ravenna was the battle that broke the mold, where the Allies dictated both the tactical and strategic pace of the battle, and also crucially decided how the battlefield itself would look.