Blood and Honor: Partisans and the SS on the Road North

August 1944

Arrigo Paladini and the partisans had been busy. It was seven weeks since the scholarly resistance leader had cheated death by jumping from the truck full of condemned men. He had put on weight in liberated Rome, thanks in part to eating as much as he could of an ad hoc wartime version of spaghetti carbonara. This was made from mixing pasta with the tinned chopped ham and eggs that American soldiers gave him from their K ration packs. He had seen the summer sunshine and woken up each morning at least halfway sure that he might live to see the following one. Other partisans from the Radio Victoria network that the OSS ran in Rome had not been so lucky. At least eighteen had been executed, either at the Ardeatine Caves in March or as the Germans pulled out of Rome. Paladini was now working with the OSS as it recruited, trained, and dispatched parties of agents northward behind German lines. For the partisans, insurrection and sabotage north of the Arno was the order of the day.

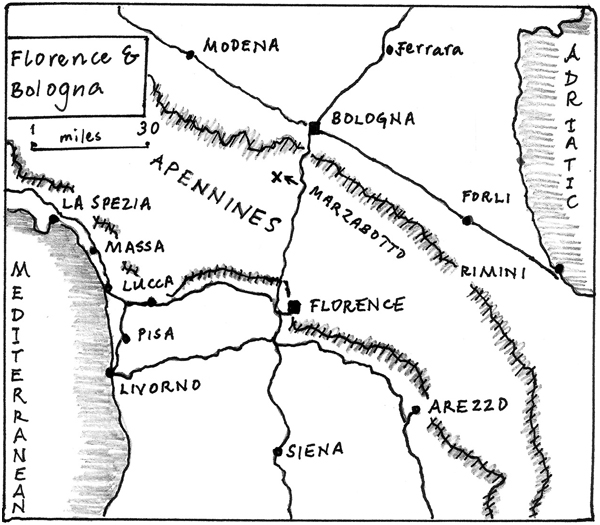

The Office of Strategic Services was working in loosely coordinated tandem and occasional competition with the British SOE. The Special Operations Executive handled British covert intelligence work in Italy along with the British Foreign Office’s spy network, the Secret Intelligence Service. The British were based at a training center at Monopoli, north of Brindisi on the Adriatic coast; the OSS, in Rome, Naples, and Corsica. Like the British, Paladini and the Americans had three priorities. First, to recruit potential political and partisan leaders from the mass of antifascist Italians who could now live and operate in Allied-controlled areas, and to train them for covert operations. These men and women were then inserted ahead of the ever-advancing Allied lines, north of the River Arno, by parachute, submarine, on foot, or by fast patrol boat. Second, they were gathering information from Italian partisans prepared to cross the German lines into British or American territory. Third, by August 1944, it was clear that the Russians, British, Americans, and their League of Nations allies were going to win the war. What became of Italy after the war was now a pressing concern. If the Germans could destroy any significant part of the economic powerhouse that was northern Italy—Turin, Milan, Genoa, Bologna—the country, bereft of its hydroelectric, banking, and manufacturing infrastructure could emerge bankrupt from the conflict and easily fragment into a regional civil war. With a full frontal attack on the Gothic Line now inevitable, and any outflanking invasion of the Balkans out of the question, the Allies were effectively opening a second front in Italy, behind the lines of the Germans and Mussolini’s Fascists.

The German Strategy

Whereas the Allies had been divided among themselves over their strategic objectives, the Germans in contrast enjoyed a political and military unity of focus. By July 1944, the Germans in Italy knew they weren’t going to be reinforced. Russia, Poland, the fighting in eastern Europe and in France had made sure of that. A rugged and drawn-out defense, followed by a gradual fighting withdrawal to Austria and the Alps, was thus their basic strategic plan, helped by their strong defensive positions and the high ground. Their tanks were better, their antitank weapons were better, and in their individual troop units, like the Allies’, morale was variable. But it was their command of the defensive that gave them the advantage in the battle for the Gothic Line. Two key factors, however, had the power to undermine this: partisan attacks from the rear and in rear areas, and the superiority in artillery, air power, and men that the Allies possessed. Kesselring’s men were effectively fighting a three-front war. First, having to respond to the increasingly erratic strategic edicts of Berlin, from Hitler, Himmler, and the OKW (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, the Supreme Command of the Armed Forces), led by Wilhelm Keitel. Second, having to confront the Allies in head-on infantry and tank assaults, supported by enormous aerial and artillery firepower. And third, having to deal with the thousands of Italian partisans in their rear areas. Since Kesselring had issued his antibandit orders in September 1943, the partisans knew they were dead if captured, so they had little to lose.

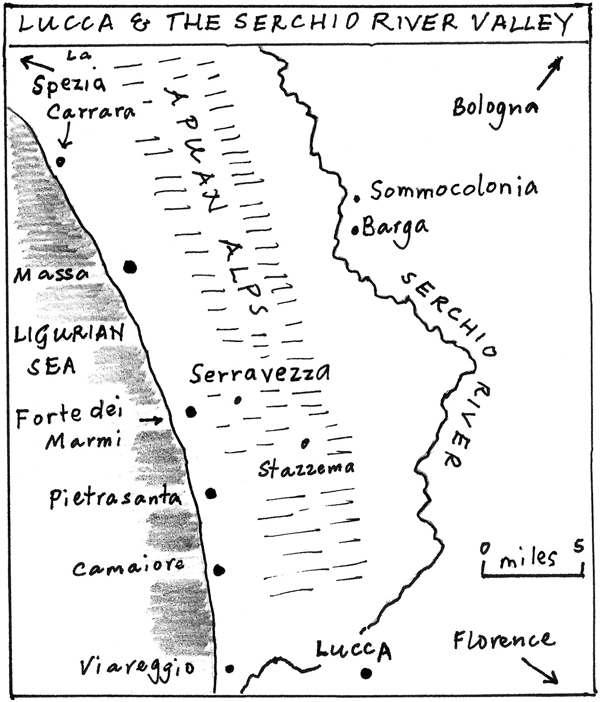

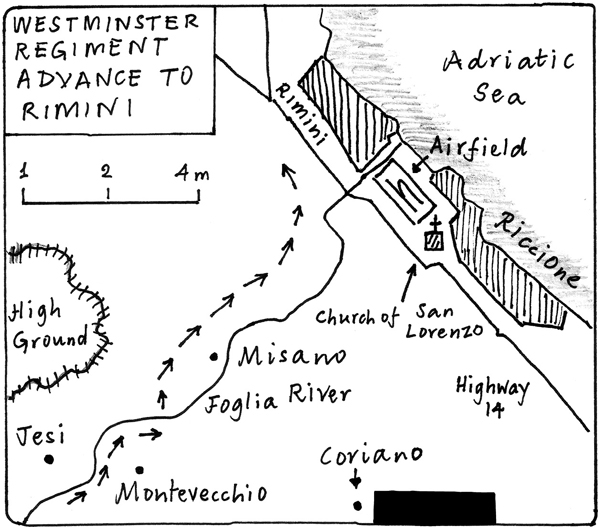

The paratroopers, SS soldiers, and Wehrmacht men needed to hold the Gothic Line positions for as long as possible, to pin down as many Allied troops in Italy as they could, and prevent their advancing into Austria, and thence Bavaria, eastward into Yugoslavia and Hungary, and north into eastern France. With a group of loyal Italian Fascist units fighting with them, they had five principal strategic and operational aims. First, to block the Allies at Rimini, Bologna, and La Spezia, on the Mediterranean, and bog them down until spring 1945 in the mud and mountains of the Apennines. Second, to fight antipartisan operations, committing atrocities as deemed necessary to subdue the civilian population and intimidate the resistance fighters, in territory they controlled on and behind the Gothic Line, keeping the areas under German and Mussolini’s Italian Fascist control. Third, to deport to concentration camps as many of Italy’s Jews and Communists as possible, and loot as much art and economic matériel as they could; by the summer of 1944, this had largely been achieved. Fourth, there was already a circle of officers within the SS who wanted to cement postwar escape routes out of Italy toward South America for senior SS and Nazi party members. Last, unknown to Hitler and the loyal circle at the OKW, some senior officers knew they had to make preparations for the postwar intelligence and political cooperation they saw coming, with the Allies against the Russians.

The Italian Partisans and the San Polo Massacre

Eugenio Calò, a Sephardic Jew from Pisa, was second in command of the Pio Borri brigade that operated in the Tuscan mountains east of Florence. His wife, Carolina, and three children were detained by the Germans at Fossoli detention center in May 1944, and then put on a train to Auschwitz.1 Carolina gave birth to their fourth child in a railway wagon. She and the family were gassed immediately on arrival in Poland. At the beginning of July 1944, Calò and his men captured some thirty German prisoners, and, despite the demands of his men that they be given a summary trial and then be executed—Italian partisans were, after all, shot immediately by the Germans—Calò refused. He insisted on taking the prisoners across the German front line and handing them over to the Allies at Cortona, southwest of Arezzo. This was a suicidal undertaking: if stopped by German troops, Calò and his men would be shot on the spot. They passed radio messages to the OSS in Rome, via Arrigo Paladini’s network. They informed the Americans that they were bringing the prisoners over for identification, crossed the two front lines, and delivered them.2

General Mark Clark had meanwhile asked for two partisan volunteers to cross back over the front lines and coordinate the arrival of the Allies into Arezzo on July 14. The Allies were increasingly taking this tactical approach: the stronger they could make the partisans in each area, they reckoned, the easier it would be to coordinate the takeover of each Italian town. Calò volunteered. This mission was successful, but on the night of July 14, he, a group of Italian civilians, some partisans, and another group of German prisoners were captured by German Wehrmacht soldiers near the village of San Polo. Despite orders, by no means did all German units execute their partisan prisoners, or terrorize civilians supporting them, but this particular army unit did. The partisans, along with some forty-eight of the village men, were taken to two villas that had been requisitioned by the Germans. Tortured almost to death, in the late afternoon the partisans and village men were taken into a field behind one of the houses. The civilians were made to dig three pits in the dry earth, baked hard by the sun. They were forced to lie in them alive: the partisans were placed in the pits heads aboveground, explosive charges were attached to their bodies, and then they were blown apart.

The following day, Sherman tanks of a British armored unit, the 1st Derbyshire Yeomanry, pulled back into San Polo after coming under heavy shellfire on the road north; they immediately discovered what had happened the previous day, and alerted the British Intelligence Corps. A Field Security Section was dispatched a mile northwest of Arezzo to the cornfields and olive groves of San Polo, which lay at the foot of the wooded hills overlooking the town. The men from the intelligence unit had been billeted on mattresses on the marble floor of a hotel lobby in Arezzo. On arrival in San Polo, they met several partisans, who showed them the mass graves.

“There was no disguising the horror that had taken place,” said one member of the section afterward. “Scraps of cloth hung on trees and there was the indescribable stench of death in the air. The partisans led us through the deserted village to a house that had been used by the German troops. We searched in the litter and debris but failed to find anything that could identify the unit responsible for these dreadful murders. However, with Teutonic thoroughness, all evidence had been destroyed or removed. Deeply saddened, we took leave of the partisans to rejoin our section, frustrated to the extreme that our efforts had been in vain, and no-one would be brought to justice for this horrific deed.”3

The parish priest told the British tankmen that the day before the Germans withdrew, they had taken all the men of the village, except himself, to a nearby olive grove behind the house they had requisitioned, made them dig three large graves, and then bayoneted the men into the graves and placed a number of explosive charges among the dead and dying.

With their new weapons, Allied liaison officers, and aggressive agenda, the partisans now carried out more and more attacks. The Germans responded in kind, translating Kesselring’s orders into a ruthless scorched-earth policy with appalling human consequences. This in turn encouraged the partisans and accelerated their operations. They had nothing to lose. The cogwheels of war often spin with a violent entropy: each event turns the wheels around it faster and harder. So it was with the partisans and the Germans. As the war moved north, inexorably, toward the Gothic Line, everything moved as one, each seemingly separate incident intermeshed as part of a greater whole.

The Reichsführer-SS and Major Walter Reder

Sitting behind Florence was one of the best-equipped and most experienced German units, the 16th SS Panzergrenadier Division of the Waffen-SS, whose divisional title was the Reichsführer-SS. Its commander was Gruppenführer Max Simon. They were directly opposite both Daniel Inouye and Eustace D’Souza on the line. This German unit had arrived in Italy in May and had taken part in the fighting retreat defending the sector in Tuscany from Grosseto up to Cecina, roughly opposite the line of advance of the Japanese-American 442nd RCT. By July, the SS men had arrived across the Arno, holding the line from Pisa down to the Mediterranean where the river pulled sluggishly into the sea.

In mid-August, Max Simon decided to detach one of his battalion commanders to move to the north of Florence, toward a mountain complex called Monte Sole, which overlooked and dominated the main highway northwestward to Bologna. This, Gruppenführer Simon had guessed correctly, would be the central focus of the American 5th Army’s attack on the central sector of the Gothic Line. Like every other German officer, Simon knew the allied assault on the Gothic Line was imminent. But where would it come? In the east, around the town of Rimini? In the center, near Bologna? Or on the Mediterranean? Simon thought it would be around Bologna, which made it vital to occupy and defend the high ground that controlled the access roads to the city. Monte Sole was a huge mountain that lay southeast of the town of Marzabotto, and was occupied by an Italian partisan unit, the Brigata Partigiana Stella Rossa, the Red Star Brigade. The battalion commander Simon chose for the mission to take this mountain was given a clear set of instructions: destroy the partisans and their support structure at Monte Sole.4 The officer chosen was SS-Sturmbannführer, or Major, Walter Reder. He needed no further orders. He prepared to move north to complete the task. His understanding of Max Simon’s orders was clear: he had said simply that there were partisans to be “deleted.”

* * *

Walter Reder was born in 1915 at Freiwaldau in Silesia (Austria-Hungary). Reder’s father had been an industrialist who had lost his job, his company, and the family’s wealth in the economic depression of the 1920s. Reder was determined from his early teens to recoup some of the family’s lost financial power and the social status that had disappeared with it. After the family moved to Austria, he went to high school in Salzburg and then to business school in Vienna. Then he joined the Hitler Jugend (Hitler Youth), where he was influenced by reading völkisch national racial literature. In 1934, at age nineteen, he ceased to be Austro-Hungarian and was granted German citizenship. He enlisted as a private in the Allgemeine-SS, its general administration body, which differed from the two other main branches of the SS: the Waffen-SS, its combat soldiers, and the Totenkopfverbände, in charge of the concentration camps. He attended SS officer candidate school at Brunswick, graduated sixtieth in his class, close to the bottom, and emerged as a young SS lieutenant desperate to prove himself.

He was then transferred to the SS-Totenkopfstandarte, Death’s Head Unit, where he was sent to Dachau concentration camp outside Munich in 1936 to lead the men guarding the political prisoners and Jews. Hoping to transfer to the Waffen-SS, he underwent a series of military training courses. But by the time of the invasion of Poland in September 1939, he was still in the Death’s Head guard units. His duties in Poland, behind the main line of the German advance, were described as “processing and dealing with Polish stragglers, Jews, and Communists.” Then came a stroke of administrative luck.

In October 1939, the Totenkopfstandarte were incorporated into a new SS infantry division, and Walter Reder was given his own platoon. Finally, he thought, the time had come for him to shine. But it was not to be. His first job was again an administrative one, as a divisional liaison officer between his unit and SS headquarters in Berlin. As the German blitzkrieg swept across Europe, the frustrated twenty-year-old of three different nationalities—Austrian, Czech, German—still hadn’t fired a single shot at one of the Reich’s enemies. But by the time he’d served as a divisional staff officer during the invasion of France in 1940, he was awarded the Iron Cross Second Class. He also got married.

In 1931, Heinrich Himmler, as head of the SS, had established the Rasse- und Siedlungsamt (Race and Settlement Office). This was in charge of approving the applications of SS men to marry. Both Reder and his fiancée, Beate, were deemed of ethnically and racially pure stock. They were married in October 1940. Life was suddenly moving forward for the ambitious lieutenant. And then came Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of Russia, which allowed him to show his true mettle. Promoted to the rank of hauptsturmführer—captain—he led his company of the Totenkopf in combat across western and northern Russia. On July 28, a month into Barbarossa, he was awarded the Iron Cross First Class. He led from the front. And on September 1, outside Leningrad, he paid the price. He was shot in the neck.

But in a typical irony of war, the young officer who had finished close to the bottom of his class at officer school was driven—by his belief in the National Socialist ideals of racial purity, ethnic superiority, and the need for German dominance over lesser untermensch, and also because he actually was an excellent combat soldier. His men revered him. So after convalescing, he returned to the Russian Front at the end of February 1942 for a year of almost continuous combat. First as a company commander, then at battalion level, Reder fought with the 1st and then 5th SS-Panzergrenadier Regiments of the division. In October of that year, he was awarded the Deutsches Kreuz in Gold—the highest class—and he took command of his own SS battalion the following February. Then, in February 1943, came the Third Battle of Kharkov.

Reder and the SS-Totenkopf Panzer Division were part of the German Army Groups Centre and South, which in a two-month battle destroyed an estimated fifty-two Soviet divisions in the southern Ukraine. The Russians had encircled and defeated the German 6th Army at Stalingrad and, emboldened, launched a huge offensive westward at the beginning of 1943. They overstretched themselves, however, were outflanked and surrounded by the panzer armies and Wehrmacht divisions of Field Marshal Erich von Manstein, and forced to give up the key city of Kharkov. It was fighting on an epic scale, across the vast, frozen winter plains of the Donetsk region. The Soviet Red Army deployed 345,000 soldiers, of whom 86,500 were killed. The Germans, weakened by Stalingrad, could put only 70,000 men into battle, of whom they lost 4,500. It was also fighting in which very few prisoners were taken—on December 5 and 6, 1943, for instance, the SS division Liebstandarte Adolf Hitler went into action in the Ukraine. In one battle, 2,280 Red Army soldiers were killed, and only 3 prisoners taken. A German tank commander remembered the noise like a frozen, crunching mulch as his armored vehicle drove over Red Army soldiers lying in their path.

(To put these casualty and prisoner figures into perspective, those incurred during the Allied invasion of Sicily in the same year were comparatively modest. The Germans called the fighting in Europe “polite.” The Americans, British, and Canadians landed or parachuted 160,000 men into Sicily—the Americans lost 8,781 killed, wounded, and taken prisoner. As mentioned, the number of men afflicted by malaria hugely exceeded the battlefield killed and wounded.)

The Germans at Kharkov triumphed through their use of tank tactics, in perfect tank country. The fighting established as German household names panzer and SS commanders including Joachim Pieper and Kurt Meyer, both holders of the coveted Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross. And it was in the fighting for the northern Kharkov suburb of Ila Jeremejewka that Walter Reder joined their ranks. The Totenkopf division, along with two others, the Liebstandarte Adolf Hitler and Das Reich, had been deployed into the shattered, frozen muddy streets of northern Kharkov after they had outflanked the Red Army and recaptured the city’s suburbs. On March 9, 1943, Reder and his company were patrolling along a semidestroyed street in armored patrol vehicles, backed up by tanks. Soviet troops had occupied the buildings in front of them, with dug-in machine guns and antitank cannon covered by snipers. It had taken the SS men four days to move from the outskirts of the city toward Dzerzhinsky Square. The fighting was street by street, house by house, room by room. One half of a squad would provide covering fire with their MG-42s, the other half would run forward with hand grenades and Schmeisser machine pistols, while armored vehicles provided heavier fire. Once the Germans closed with the Red Army, it was time for pistols, bayonets, submachine guns, and knives, and even the schanzzeug, the stamped steel German entrenching tool, whose edges the men would sharpen. It was while leading and directing one such attack that Reder suddenly saw a bright red and yellow flash coming straight at him from a window, then a huge explosive thump on his lower left arm. He came to in a field hospital, the limb amputated.

By the time he was evacuated and sent to Poland, he had been decorated for gallantry six times and was SS to the tips of his remaining four fingers and one thumb. Following the wounds and his leadership at Kharkov, he received the coveted Ritterkreutz, the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross. He was then sent to Poland with another SS Panzergrenadier battalion, this time tasked with the destruction of the Warsaw ghetto. The fighting was tough. Himmler was to say, self-congratulatingly, that the battle for Warsaw was the hardest the SS had fought, “comparable with the house to house fighting in Stalingrad.” Reder then moved south to Italy.5 The Polish survivors of Warsaw went to Treblinka.

Following successful completion of the Warsaw mission, Reder was transferred to the newly formed 16th SS Panzergrenadier Division, with the rank of reichsführer-SS. He arrived in Italy in May 1944, his main responsibility being antipartisan operations, a job he took to extremely quickly, combining his experience of combat in western Europe and Russia, and his eradication of the Warsaw ghetto. For SS officers like Reder, raised and trained in the decade before the war on an unrelenting diet of National Socialism, Aryan superiority, and racial eugenics, the enormous variety of nationalities fighting for the Allied forces in Italy came as a surprise. They had regarded the Red Army as borderline subhuman, and taking prisoners in Russia had at best been academic. The racial stereotypes Reder learned at Junker officer school and from his völkisch reading—that Jews, Slavs, Negroes, non-Germans, Communists are inferior—would have been challenged by the fighting skills and determination of the vast variety of units deployed by the Allies. Poles, Moroccans, Indians, African Americans, Japanese Americans, and Gurkhas had consistently gone toe-to-toe with the SS and elite paratroopers across Italy and proved an even match.

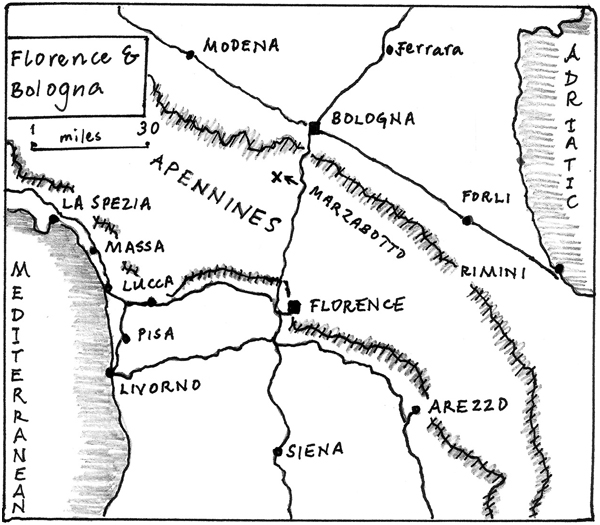

The Massacre at Sant’Anna di Stazzema

As an SS officer, Reder had three superiors to whom he was answerable. First was his immediate commanding officer, Max Simon. His ultimate superior was Obergruppenführer Karl Wolff in Rome, head of the SS in Italy. But as a ground infantry commander, he was also under the command of the highest-ranking German officer in Italy, Kesselring himself. By July 1944, Kesselring’s staff officers estimated that the partisans had killed up to 5,000 Germans and wounded as many as 20,000. The more the number of German casualties rose, the more the Luftwaffe field marshal was determined to bring their guerrilla war to a halt. Chaos in his rear areas meant his troops in Italy risked becoming isolated from their lines of supply northward. It was of little use being able to beat the Allies or hold them at arm’s length if he faced a civil war behind the lines. So he decided to do something about it, using the most brutal tactics, stepping up the pace of anti-bandenbekämpfgung6—actions against partisans, or bandits, one of Himmler’s priorities—in a small mountainous area of western Tuscany that lay southwest of Florence, overlooking the Mediterranean coast. He intended to teach the partisans a lesson. In August, the Italian civilians in the mountain villages of San Terenzo Monti and nearby Sant’Anna di Stazzema experienced these tactics.

On the night of July 14 and 15, a partisan group that called itself Olive Tree had broken into a barracks in the coastal town of Carrara. It was one of a series of seaside towns that lay directly in the path of the Allies as they advanced northwest up the coast toward the key ports of La Spezia and Livorno. This strip of littoral is overshadowed by the Apulian Alps and, farther to the east, the Apennine mountains. Carrara in particular sits beneath steep slopes sixty-five hundred feet high, where the mountains contain huge quantities of white marble. Hundreds of years of excavation had removed vast amounts of the stone to make centuries’ worth of famous Italian statuary. Michelangelo’s preferred marble came from Carrara. The shining white faces of the quarries sit surrounded by trees and scrub. Fine white dust spreads across nearby slopes. American soldiers such as the 442nd Regimental Combat Team were, by now, less than a week to the south, and the partisans decided it was time to liberate Carrara and surrounding villages.

So in early August, armed with the B 38 submachine guns and Carcano rifles they had stolen from the barracks, the guerrillas made for the hills above this strip of the Tuscan coast. In a confused nighttime firefight in the hillside village of San Terenzo Monti, they killed everyone stationed at the small German garrison, except one soldier who fled. Responsibility for the German response was passed to the 16th SS.

On the morning of August 12, one of Reder’s fellow officers, SS-Hauptsturmführer Anton Galler, led the men of the 2nd Battalion of Panzergrenadier Regiment 35 into the mountains above Lucca. This old walled citadel sits at the base of the foothills of the Apulian Alps, which run parallel to the Mediterranean coast of Tuscany. The German troops drove up to Sant’Anna di Stazzema, which lies several miles above Lucca. German army and SS troops, as well as Italian Fascist soldiers, moved toward the village from four directions of attack. En route, in the hamlet of Vaccareccia, seventy people were locked in a stable and murdered by soldiers with hand grenades and submachine guns, and then finished off with a flamethrower. They repeated this in the nearby hamlets of Franchi and Pero.

They surrounded Sant’Anna, which consists of a small church in the center of a grove of trees, farm buildings, and old stone houses. The SS men started to round up all the villagers in an open space in front of the church. One of Anton Galler’s subordinate officers who was commanding a unit that day was SS Untersturmführer—or lieutenant—Gerhard Sommer. He was a veteran of the invasion of France and had recently been posted to Italy. He and his men undertook the task assigned to them with ruthless efficiency. They gathered the men, women, children, and babies in the square, as well as in a number of barns, stables, and basements. Once the population of Sant’Anna was centralized, the executions began.7

The SS herded the largest group of villagers in front of the church, which was enclosed by a wall. There was only one entrance, so this tiny piazza became a trap. The village priest, Don Fiore Menguzzo, stood in front of the villagers trying to protect them. An SS man shot him dead. The Germans then used machine pistols and MG-42 machine guns, set on tripods at the entrance to the space in front of the church, to kill everyone in it. Between 107 and 132 people died in front of the church, and the SS reportedly then set some of their bodies on fire with flamethrowers. Then they threw hand grenades into the buildings where other people were hiding. The victims that day reportedly included Anna Pardini, three weeks old, and eight pregnant women. Surviving witnesses say that one of these expectant mothers, Evelina Berretti, had her womb cut open with a bayonet, and then her unborn baby was pulled out by the legs and executed. Inside the church, the soldiers used the pews to make a bonfire to dispose of the bodies. This all took three hours. The soldiers then sat down in the shade outside the burning village of Sant’Anna and ate lunch rations that their headquarters had issued them the night before.

On the way back down the mountain, the SS killed another 20 people in two other clusters of houses, bringing the day’s death toll in the area to an estimated 560 people, of whom 75 were under ten and the oldest eighty-six. It was the second-largest individual killing of civilians in Europe by German troops to date, that was not part of either Einsatzkommando actions or the mass killings of the Final Solution. It was surpassed only by the massacre at Oradour-sur-Glane in southwestern France in June of the same year. There, SS men of the Das Reich Division, en route to Normandy, executed 642 civilians in a small town near Limoges as a reprisal for attacks by the French Resistance.

The Reichsführer-SS, however, didn’t stop at Sant’Anna di Stazzema. A week later, on August 19, 1944, a convoy from Walter Reder’s reconnaissance battalion wound up the mountain road to San Terenzo Monti. This was the hamlet where the partisans had killed the small German garrison in late July. Stopping in the village, many of whose inhabitants had fled two days previously during the fighting between Germans and partisans, Reder’s men dropped the tailgates of their trucks. They took out fifty-three Italian men, prisoners from the prison in Pietrasanta, one in the string of towns that lay on the Mediterranean coast before La Spezia.8 The men were taken into the neighboring vineyards, where they were tied around the neck by wire nooses from the concrete bollards and heavy wooden posts that supported the trellises of the vines. Over the course of the afternoon, German soldiers shot or beat them to death.9 The message to the partisans from Walter Reder and Anton Galler was clear: if we don’t find you or kill you, we’ll just find the civilian population instead.