Dug-In Defense: The German Plan

August–September 1944

In the middle of August, the Allies landed on the southern coast of France, outside Nice, in the amphibious invasion Operation Dragoon. They faced little resistance and headed north through the valley of the Rhone River. The Red Army crossed from Poland onto the boundary of East Prussia itself, and the Americans prepared to invade the Philippines. While the war was being fought on its three other main fronts in a fluid manner, with one side advancing, the other retreating, this was not now the case in Italy. By August 15, the Allied armies had arrived up against the defenses of the Gothic Line and were preparing to attack them. The Germans were largely dug in to static positions, trying to work out where the Allies would attack first. The latter were characteristically disagreeing among themselves where their assault should begin. And then they had a stroke of luck.

In northern Italy in the fifth year of the war, command responsibility often landed on young shoulders. Mino Farneti, a young Italian, had been eighteen and just out of high school when the war began, and he had luckily managed to avoid being drafted into the Italian army. He was from Ravenna, north of Rimini, a two-thousand-year-old classical city that had once been the capital of the Western Roman Empire. It was the site of eight famous early Christian churches, and in 1318 the poet Dante Alighieri, in exile from Florence, took up residence there. (He eventually died from malaria contracted from the ubiquitous mosquitoes that bred in the marshes and canals surrounding the city, and linking it to the sea.) Ravenna was old, rich, and beautiful.

By the time Farneti was nineteen, he was already evading both the Germans and Italian Fascists and was running messages on his bicycle for the local resistance group emerging around Ravenna. When the Italian army collapsed after the Cassibile Armistice with the Allies in 1943, Farneti, brave and resourceful, couldn’t wait to join the partisans and fight. Three partisan groups had sprung up in Ravenna, each with a different political allegiance and agenda. By the summer of 1944, Farneti had established his radio set in a farmhouse on the San Fortunato Ridge, one of two that overlooked from the north the pastures outside Rimini. He had organized three different drop zones onto which the Allied Dakota transports could parachute men and arms. If his first radio set was compromised by the Germans’ never-ending sweeps with their radio-tracking equipment, one of his colleagues had a second hidden on the slope behind a farmhouse. Another partisan outwitted the Germans by keeping a radio inside a very busy, very active beehive. Even when German search parties had been inside the farmhouse itself, headsets attached to radio-tracking equipment mounted on a truck outside, they had been unable to locate the radio set in its honey enclave, even when it was switched on and therefore emitting a low signal.

Along with an estimated 1,200 colleagues from the partisans’ Garibaldi Brigade, the operational remit of Farneti and his colleagues was simple: to make life as difficult as possible for the German defenders behind the lines, and to cooperate as much as possible with British and American SOE and OSS missions in order to be able do this effectively. The Americans, based in Corsica and Naples, and the British at their SOE headquarters and training center at Monopoli outside Bari, were making regular airdrops to the partisans. Farneti’s group had already received three radio sets, as well as large amounts of arms: their orders were to concentrate on attacking the Germans along the length of the Gothic Line, and it was for this purpose that he had moved south from his hometown in Ravenna. Kesselring was aware of the partisans’ successes and the threat they posed. One high-ranking German general stopped traveling with any flags, insignia, or identifying marks on his car. Another, Brigadier General Wilhelm Crisolli, commanding a brigade on the Ligurian coast outside Genoa, died when his staff car was riddled with machine-gun fire in an ambush.

One day in August, a group of Italian partisans were waiting behind some bushes on the side of a road near Rimini, when they saw a German motorbike and its sidecar coming toward them, gunning along the highway. The partisans were cautious. In their experience, the soldier sitting in the sidecar often had an MG-42 mounted in front of him, and it wouldn’t be the first time the combination of the motorcycle’s speed and maneuverability and the machine gun’s firepower had proved a lethal offensive mix. So, with Sten guns and Carcano rifles cocked, the partisans let the Germans come close. Then they opened fire. The driver and the officer in the sidecar never saw the Italians who ambushed them, and were both dead before the BMW Zündapp motorbike came to a crashing halt. Mino Farneti, who led the small group of four partisans, was only twenty-three that summer.1

As the wheels of the motorbike combination still turned in the ditch, Farneti and the men with him searched the major’s pouches and briefcase. They pocketed his Luger pistol, watch, and spare 9mm ammunition, and they took the bread, sausage, and cigarettes that the driver, like many other German soldiers, possibly stored in his gas-mask case. They would also have taken his MP 40 machine pistol, his six magazines of ammunition, and the precious canvas carrying pouches they came in, attached to the German’s leather belt in sets of three. But it was only as they rifled hurriedly through the officer’s briefcase and knapsack that Farneti realized that on the dusty road outside Rimini, lined with vineyards, they had struck gold. The German major was carrying a complete set of plans for the defenses on the eastern end of the Gothic Line.

The immediate concern for the partisans was simple: How to get the papers to the Allies as quickly as possible? By mid-August, their front line was still around Florence, so they told a partisan courier to take them to a fellow agent in Milan. From there they were escorted by a combination of couriers to the headquarters of the OSS across the Swiss border in Lugano. The lakeside town acted as the headquarters not just for the Office of Strategic Services but also as a main meeting and transit point for the British Special Operations Executive, based in Berne.

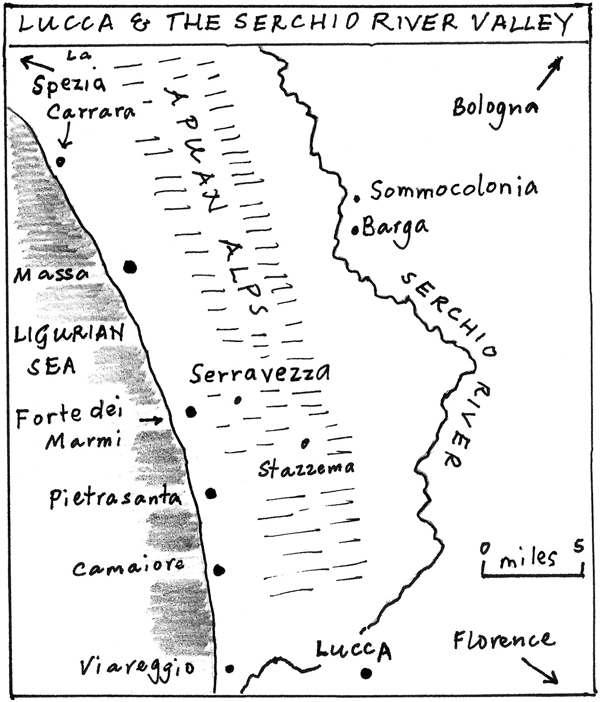

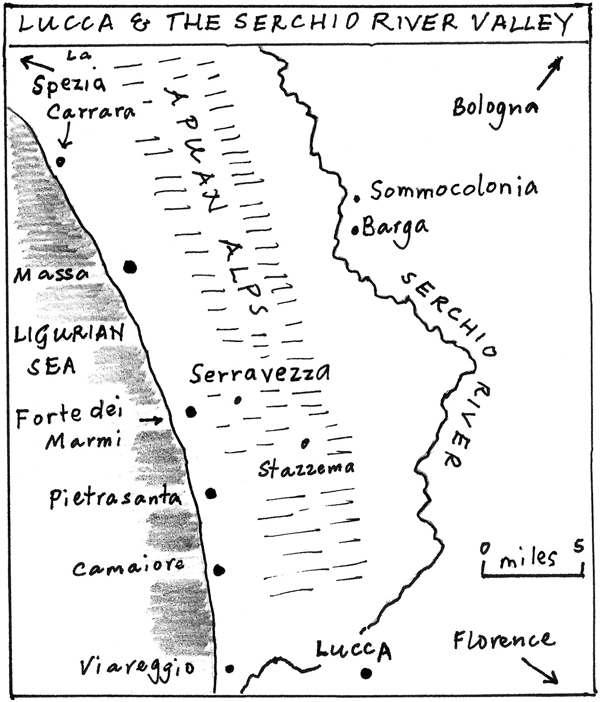

A few days later, on the western end of the Gothic Line, another group of partisans got lucky. They succeeded in stealing another set of plans that showed the German defenses that stretched from Bologna in the center toward the Mediterranean. These partisans were based in and around the old medieval walled town of Lucca in western Tuscany, twenty miles from the sea in the shadow of the Apennines. In late summer 1944, the weather was hot and calm, and the German soldiers patrolling around the town took cover from the afternoon sun in the shade of the palm, magnolia, and cypress trees. The Americans were still ten miles to the south, advancing steadily.

So when the partisans in Lucca got hold of the set of German plans, they had two choices. Take them across the Allied front lines ahead of them and risk capture by the Germans, immediate torture and execution, and the loss of the documents? Or take the safer route by smuggling them north to Switzerland? The disadvantage of this was having to cross miles of German-occupied territory, thus losing precious time. They chose the first option.

The plans were voluminous: heavy paper with detailed markings in colored wax pencil. Any partisan carrying them had to imagine he would be stopped and searched by at least one German checkpoint or patrol, so it was out of the question to carry them in a bag, in the lining of a jacket, or taped around the legs. So the most important parts of the maps were cut into a long strip, showing the geographical line from La Spezia on the Mediterranean to Bologna. A partisan then divided the papers in two, folded the plans into tight compact squares, and put them in the soles of his boots, under the leather inlay beneath his socks. It meant he had to walk slowly lest the crunching sound of the papers give him away. Leaving Lucca before the curfew, he set off across the fields of corn, the orchards of lemons and peaches, and the stands of ilex and cypress trees interspersed with irrigation ditches. He crossed through territory controlled by the SS soldiers of Max Simon’s 16th Reichsführer-SS Division, which was the part of the German 14th Army responsible for this part of the western sector of the Gothic Line. The Allied front line lay ahead of the partisan courier. This was ground occupied by the Indians of the Marathas deployed south of the River Arno, and by the Nisei of the 442nd between them and the sea. Once across the front, the small partisan group headed south for Siena and contacted the OSS. The plans headed immediately to General Mark Clark’s HQ.2

The Germans and Their Defensive Positions

The plans confirmed what the American general had most hoped: Kesselring was expecting an attack at the western end of the Gothic Line, where it hit the Mediterranean. The weakest part of the German defenses was exactly in the middle, where the 14th and 10th Armies interlinked in the mountains outside Bologna. British General Harold Alexander wanted to storm the line at this point, cut through the Apennines, and fan out with his armor into the plain of the River Po. The Allied landings in the south of France on Operation Dragoon—that both Churchill and Clark had bitterly resisted—had reduced the combined strength of the British 8th and American 5th Armies to some 150,000 men, or eighteen divisions. Up against them were two German armies that, with their reserves and an army corps in the Ligurian mountains above Genoa, consisted of nearly thirty divisions. So while both sides were unevenly matched in terms of men, the Allies had the massive advantage of air superiority, while the Germans held the high ground and had had ample time to prepare their defenses. Although the Allies had a numerical superiority in tanks and artillery, the terrain counted against them: heavy artillery pieces had to be towed, driven, pushed, hauled, and dragged up the mountainous terrain of central Italy. Until the Allies crossed over into the plain of the Po, their superiority in tanks gave them only a small advantage. And the Germans’ artillery was well dug in, camouflaged, and commanded every single main road, river, bridge, mountain approach, crossroads, town, and village.

The partisans were able to give a very clear intelligence picture, to both the OSS and Mark Clark’s headquarters, of what life was like in the territory occupied by the Germans. Partisans and their families had been conscripted as forced labor for the Germans, so they could give an accurate appraisal of the exact strengths and weaknesses of the Gothic Line defenses. In cities like Bologna, partisans reported that the German officer cadres were leading a busy and enjoyable social life. Italian Fascist officers and their sympathizers gave parties all the time: there was no shortage of wine, grappa, and vermouth, and no shortage of friendly Italian women who still thought that the war could swing back into the Germans’ and Mussolini’s favor. Collaborating Italian women frequently worked as prostitutes. There was little shortage of food for the Germans. Allied air attacks were frequent but caused as much damage and disruption to the civilian population as to the Germans, and weakened support for the British and Americans, mostly in the cities and towns that were hardest hit.

The plans and information smuggled across the lines contained information about the German high command structure too. From intercepted coded communications, cracked by Ultra, the Allies had already built up a clear picture of the commanders they were facing on the Gothic Line. One of the most capable German generals in front of them was Luftwaffe General der Fallschirmtruppe Richard Heidrich. He was a hugely experienced and highly decorated paratrooper who had fought as an infantryman in the First World War, jumped with German airborne units in the invasions of France and Crete, fought in Russia, and parachuted again in advance of the Allied landings in Sicily. He’d fought at Anzio and, crucially, during the four battles of Monte Cassino. It was his men who had held up the Allied advance so doggedly during their attacks on the site of the Benedictine monastery. His fallschirmjäger (paratroopers), the so-called Green Devils, were among the best troops the Germans had, past masters of dug-in, defensive fighting.

The partisans reported that after withdrawing northward from Rome toward Florence, Heidrich had briefly based the headquarters of his 1st Parachute Corps in a Tuscan villa outside the town of Regello. The night before he and his HQ departed north, they hosted a large and grand party for the officers from their own and other German units. But the partisans had connections among the Tuscan waiters and gardeners, and via the OSS, the exact location of the villa and the time of the party was passed to the Allied Desert Air Force in Corsica. As the German paratroop officers relaxed after almost a year of constant combat, the sky overhead groaned and rumbled as American B-24 Liberators flew in and unloaded sticks of 500-pound bombs on the villa and its surroundings. The good news for the Allies was that Heidrich’s garden party had been ruined. But the bad news, as passed on by the partisans, was that Heidrich’s crack parachute corps had moved northeast and taken over the defenses in the key coastal town of Rimini, one of the Allies’ main targets.

The German paratroopers near the Adriatic town were doing more than preparing defensive positions. It was summer, and they were reportedly making the most of it—taking advantage of the sun to go swimming naked, occupying any number of hotels, and interspersing their preparations with forays into the countryside to pick tomatoes, grapes, and melons with which to augment their rations. One detachment of paratroopers, searching through a beachfront hotel in Rimini, found a letter from two women, sent from Germany. In early summer that year, the women had been planning to vacation in German-occupied Italy, which was a relatively safe destination until the Allies broke through the defensive lines outside Rome and headed north. Was it possible, the German women had asked in their letter, to go swimming in the nude in the sea at Rimini? Courteously, given that they were preparing for an enormous countrywide attack by the Allies, the German paratroopers wrote a letter back, saying that yes, everybody was swimming naked in the Adriatic that season.3

The German Generals

In the center of the line, opposite the Marathas, were not only the 16th SS but also a division of infantry from Berlin Brandenburg. Their morale was low, reported the partisans, mainly due to the eccentric and merciless leadership of their commanding major general, who was a tireless advocate of the tactical approach of fighting to the last man. The Allies knew Generalleutnant Harry Hoppe well. He was an Evangelical Christian from Braunschweig in eastern Prussia who stood five foot eight and weighed 126 pounds. He had been a soldier since 1914, when he enlisted as a private. Continually wounded, continually decorated, and continually promoted, by the summer of 1944 he was a major general in charge of the defense of Ancona on the Adriatic coast south of Rimini. He’d already won the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross on the Russian Front, and he was to be mentioned in dispatches for his tenacious and highly skillful defense of the Adriatic port under a blistering attack by the Poles in late June. Nicknamed “Stan Laurel” by his men, because of his lack of height and facial resemblance to the popular comedian, he had changed his name from Arthur to Harry in February 1943 as he thought it would make him more popular with his men. Whether it did is doubtful. A newly arrived detachment was hardly reassured when greeted with, “You have come here to die and to be quick about it.”

Using clichés such as “They Shall Not Pass” and “Better Death than Captivity” in front of parades did not inspire confidence in his men, a thousand of whom chose captivity over death when the unrelenting Poles of General Władysław Anders’s II Corps overwhelmed them at Ancona. The survivors of the 278th Infantry Division were then transferred to central Italy, where they were aghast to discover that opposite them was another enemy just as hard as the Poles: the Marathas of the 21st Indian Brigade. And to make things worse, behind them were the partisans. Even the remorselessly upbeat General Hoppe was obliged to describe Easter 1944 in his diary as “a somber festival” after partisans blew up a Good Friday cinema performance, killing a number of his men as they celebrated the holiday. But contrary to morale, which was variable, the quality of German leadership across Italy was high. The style of generalship varied, with determined leaders like Heidrich, Hoppe, and the 16th SS’s Max Simon. They led their men with a combination of tactical capability, inspiration, discipline and, in the case of the SS, ruthless devotion to a cause.

Yet morale among the German soldiers was variable. They knew they were well led, predominantly well equipped, and had control of the terrain. But by mid-1944, they were under no misapprehensions that their Italian allies were anything other than lackluster and unreliable. Allied air strikes were a constant but predictable worry. But if and when everything went wrong, they knew from long experience since Sicily and North Africa that they could surrender to the Americans or British or Canadians and stand a good chance of making it to a POW stockade alive. Italy was not Russia, and the Allies were not the Red Army. Prisoners were taken. It was the Italian partisans who were the unknown, constant fear. It was impossible to tell where they would strike next. Any German vehicle traveling in a convoy that did not contain an armored car or tank was a target. Small units based on isolated stretches of the line—and the Gothic Line snaked across some of Europe’s most rugged, isolated mountainous terrain—had no idea who could be moving in front of their trenches, dugouts, or fortified houses in the darkness. Partisans? Wolves? Deer? Marathas or Gurkhas? It was impossible to tell.

And out of the line it was impossible to relax and feel secure. Vicious reprisals against partisans and the civilian population had, since the massacre at Sant’Anna di Stazzema, become more frequent. So the partisans had no qualms about attacking the Germans wherever or whenever they found them. The individual political leadership of each partisan group, and the SOE and OSS officers who operated with them, continually reiterated to the partisans the operational imperatives stressed by Jock McCaffery, the head of the SOE in Berne: “offensive military action and sabotage against German targets in support of the advancing Allies’ war aims and strategic plan.”

So the Germans, in many cases, felt just as vulnerable to attack from behind as from the front. Way behind the Gothic Line were units stationed in the region of Liguria. This is a region of mountains that rise above the Mediterranean coast west of Genoa to the French border. The string of seaside towns—Savona, Imperia, San Remo—sit in the shadow of the mountains. Since the late 1870s, they had been the seaside resorts of choice for the inhabitants of northwest Italy; Bordighera, with its villas and carefully designed gardens, was a favorite of the British upper middle class. Each town had a long sandy beach with some rocky coves, a coastal railway line leading behind it, a little station, and then the town itself built up the gradual slopes that led into the limestone mountains. These were covered in harsh scrub of olive, ilex, and small oak trees.

Among the other German generals who led through a combination of bravery and enormous personal example was an officer who commanded a unit in this part of Italy. The 90th Panzergrenadier Division had been pulled back to the Gothic Line after the fighting at Monte Cassino. It was commanded by Major General Ernst-Günther Baade. He’d been a Rhodes scholar, winning a sports scholarship to study at Oxford University before the war, and was well known on the European equestrian circuit. He loved Scotland.4 He frequently took to wearing kilts, and during the fighting at Monte Cassino, he announced the names of Allied POWs over the English and American radio frequencies so their unit commanders could know their men were alive. He had been wounded in North Africa during the fighting at Bir Hakeim, before the battle of El Alamein. Colleagues in the Afrika Korps remembered him as a legend, who was known to go into battle dressed in a Scottish kilt and carrying a claymore, a double-edged Scottish medieval broadsword. Wounded twice and decorated for gallantry nine times, he was adored by his men.

The Adriatic sector of the Gothic Line, from Pesaro to the Muraglione Pass near Florence, was under the command of an aristocratic Prussian officer, Generaloberst Heinrich von Vietinghoff, and his 10th Army. Having lied about his age (he was fifteen) to join the army during World War I, he was a tank officer during the invasion of France in 1940, a general by the time Hitler’s panzers pushed into Yugoslavia, and a tank corps commander in Army Group Centre during Operation Barbarossa. It was in Russia that he earned the nickname “Panzerknacker,” Tank Breaker. And it was in Italy, commanding the 10th Army on the Gustav Line, that he was awarded the Oak Leaves to accompany his Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross. It was he who reportedly developed the defensive concept of removing the 75mm guns and turrets of Panther tanks from their chassis and digging them into concrete revetments as a fixed gun emplacement. The turret mechanism and its traversing system was embedded in a concrete bunker at ground level, tactically sited, and then camouflaged. This allowed the tanks’ firepower to be deployed on mountainous terrain in very strong defensive positions where tanks themselves do not have the capacity to maneuver.

The eastern end of the Adriatic sector was under the control of LXXVI Panzerkorps, commanded by General Traugott Herr, another tank officer who had fought in France and Russia, been wounded, and decorated for gallantry. He had five divisions—one panzergrenadier, three infantry, one mountain—and Richard Heidrich’s paratrooper corps, itself with three more divisions. One of the infantry units, the 162nd, was primarily composed of Turkoman troops recruited from central Asia. Backing them up to the west, toward Florence, was Lieutenant General Valentin Feurstein’s LI Mountain Corps, which had only two actual jäger (mountain) divisions, and five line infantry divisions, one of them Italian.

From Bologna west to the Mediterranean was the fiefdom of Lieutenant General Joachim Lemelsen and his 14th Army. His deputy was another Anglophile and Oxford Rhodes scholar—Lieutenant General Frido von Senger und Etterlin, a Bavarian and devout Catholic, who was also a lay Benedictine; he commanded the army’s XIV Panzer Corps. This was made up of one panzer division, one infantry division, and SS-Gruppenführer Max Simon with the 16th Reichsführer-SS Division, stationed west of Florence. To the far west, and north of the Gothic Line in the Mediterranean province of Liguria around Genoa, were two more German divisions and two Italian. In and around the mountains and passes on the French-Italian border was the German LXXV Corps. This was made up of three infantry divisions, one of which was the 90th Panzergrenadiers of the Claymore-wielding Ernst-Günther Baade. Another four reserve divisions were spread behind the German lines between the Gothic Line and the Alps, making thirty-one divisions in total facing the Allies. Many were understrength.

In addition to the partisans’ military operations behind the lines, they had been busy sabotaging the construction of the fortifications of the Gothic Line. The Germans had started building these around the time of the armistice, in September 1943, when Italy surrendered. They conscripted thousands of Italians as forced labor. Partisans, naturally, were among them. They couldn’t make any difference to such factors as the layout of minefields, or the quality of weapons the Germans were using, but they could directly affect the building. Straw, hay, gravel, and the bare minimum of cement were used where possible, meaning that a pillbox made of the lowest quality concrete would buckle under Allied fire. Gun emplacements were built facing twenty or thirty degrees the wrong way, and only when German troops placed their MG-42s or their antitank weapons in them did they discover, too late, that they didn’t have the necessary commanding view of approach roads and valleys. Barbed wire was stretched in front of trenches and gun positions, but it wasn’t attached at either end to anything but a bush. Trenches were built on slopes that flooded easily in autumn and filled with snow in winter. Pillboxes were positioned by streams and rivers that would fill the concrete bunker with water through holes low on its sides. The partisans kept detailed notes of these soft spots in the German defenses.

So across the Gothic Line the Germans waited. On the road toward Bologna, Walter Reder and his SS reconnaissance battalion headed toward the enormous mass of Monte Sole that overlooked the road north from Florence. Brigadier General Max Simon had deployed the remainder of the 16th Reichsführer-SS on the north side of the Arno, opposite the 34th U.S. Infantry Division, on whose flanks were Sergeant Daniel Inouye and the 442nd RCT. General Harry Hoppe’s battered but disciplined 278th Infantry Division was north of Florence, opposite the Maratha Light Infantry. General Ernst-Günther Baade and his 90th Panzer were far to the northwest, spread across the Ligurian terrain right up to the outskirts of the city of Turin, in the shadow of the Alps. On the Adriatic coast at Rimini, the talented paratrooper General Richard Heidrich agreed with Kesselring’s strategic evaluation that the Allies would attack in the center or west of the Gothic Line. So in the third week of August, he went on leave. His paratroopers shook out across the city and surrounding countryside, preparing defensive positions that covered roads, open country, and the approach routes to the San Fortunato and Coriano Ridges that dominated the flat land outside the port. Mortars, 88mm guns, and MG-42s were sited, minefields laid, antitank guns hidden inside haystacks and abandoned houses, and trenches dug.

In the church of San Lorenzo in Strada, outside the seaside suburb of Riccione, the Green Devils dug in. The building dominates the main road that leads northwest from Riccione to Rimini airfield, and then straight up the coast into the heart of the port itself. Any Allied attack up the seacoast would have to go through Riccione, and then directly at the church. Paratroopers from Heidrichs’s 1st Fallschirmjäger Regiment took over the church in the third week of August. One of them was only seventeen that month. Jäger Helmut Bücher was born on Christmas Day 1926. He was from Otzenhausen, a town in the German Saarland that lies southwest of Frankfurt, only twenty miles from the border with eastern France. His hometown dated back to the days of Julius Caesar’s wars in Germania in 30 B.C., and just north of it is one of the oldest surviving Gothic settlements in Europe. Bücher had enlisted in the paratroopers when he turned seventeen, and it was a great source of pride to him that he had been posted to the 1st Fallschirmjäger Regiment. Only in late June had he joined his unit. Most of his comrades were survivors of Monte Cassino. Several had parachuted into the vineyards of Crete in 1941. A few, a hard, central cadre, had been in Russia and France.

They dug trenches and a tunnel connecting the houses surrounding San Lorenzo in Strada to the crypt of the church; they’d learned the technique in Russia and at Monte Cassino. The defenders could run from one position to another without showing themselves, and vacate a house or building when it came under sustained tank or mortar fire, reappearing in the next house or garden or field or farm building. They knew from Cassino and the fighting in the mountain towns and villages of southern Italy that underground dugouts were vital. The Allies relied heavily on artillery bombardments to soften up a target: the German paratroopers would sit out the barrage, then the moment it stopped, emerge aboveground and instantly get their MG-42 machine guns into preprepared firing positions. They zeroed in on the tanks that often spearheaded the advance with antitank guns dug in up to a half mile away. The fall of shot of 81mm mortars was cross-mapped onto individual paths of advance, paths of retreat, and the areas of cover where the Allied infantry would hide and wait. The fallschirmjäger also prepared an escape route behind the church that would expose any Allied soldiers chasing them to the fire of tanks and machine guns stationed behind them as the next line of defense.

Helmut Bücher felt he was in the right place, at the right time, as he dug trenches, made a fire to heat food, carried belts of 7.92mm cartridges for the machine guns, and got ready for an attack his sergeant had told him could not be far away. He and colleagues walked the ground in front of and around their positions in the church and surrounding houses. They paced out distances—one, two, four, six hundred yards. Then they marked particular walls, low-hanging branches on notable trees, and the sides of visible houses with whitewash crosses. This would tell the defenders the exact range of their attackers once battle was joined. Bücher had told his parents in a letter that he thought he was defending all that was right and good about Germany. But as he prepared the position in front of the church outside Rimini, he wondered if he would see his eighteenth Christmas.5