4

The paleoanthropology of East Africa goes back to the 1920s, when Louis Leakey started searching for evidence of ancient humans in Kenya and Tanzania. At first with other colleagues and later with his wife, Mary, Louis investigated dozens of sites. They found ancient human skeletal remains, some of the earliest tools, and ape fossils that he believed might be forerunners of Australopithecus.

The most promising of their sites was Olduvai Gorge, where the Leakeys worked for many years. There, for countless millennia, sediment had settled in streambeds and lakeshores, scattered with animal bones and stone tools stacked one atop the other like an ancient layer cake, until erosion cut through like a knife, forming the gorge. The deepest part of the site was the oldest, known as Bed I. And in those deep sediments, Mary and Louis had found rudimentary stone tools that they called “Oldowan.”

In 1959, Mary found fossil hominin teeth there as well. Working over a few weeks, she and Louis recovered the pieces of a marvelous skull, almost complete. Louis called it Mary’s “Dear Boy,” and they suspected they had found the maker of their Oldowan tools. By their best reckoning, based upon the extinct animal fossils found at the site, the tools and the skull were a bit more than a half million years old. In a short paper they described their discovery, giving it the name Zinjanthropus boisei. The world came to know Mary’s “Dear Boy” as “Zinj.”

The “Zinj” skull

A month after Mary had found the first teeth, the Leakeys brought the skull to Johannesburg to share with Raymond Dart and Phillip Tobias and to compare their find with South African fossils. Zinj had vastly larger molars than africanus but many of the same features as robustus. As other scientists learned about the Zinj skull, many of them considered it a close-enough match to the South African robustus that they rejected the Leakeys’ idea that it was a new species. Today most accept boisei as a separate species but group it as a close relative of robustus.

During the Leakeys’ next field season at Olduvai Gorge, they discovered two fragments of skull, a jaw, and part of a hand that clearly came from a creature with a bigger brain yet smaller jaw than Zinj. Later, they unearthed more skull and jaw pieces, all from a similar kind of hominin. The result was plain: Another creature, closer to humans, had lived at Olduvai near the same time as Zinj. Perhaps this species, not Zinj, was the toolmaker.

The Leakeys assigned the new fossils to a new species, which they named Homo habilis. The name, which meant “able man,” reflected their hypothesis that habilis had made the stone tools in Bed I of Olduvai. The idea was that the invention of stone tools had set us on a human path, triggering evolutionary changes toward larger brains and hands that could use tools. The new fossil hand seemed well suited for tool manufacture, including broad fingertips and a long thumb. Yet the habilis skulls suggested brains just half the size of those in most people living today.

The most unexpected discovery came in 1961. Physicists at Berkeley had developed new methods for dating ancient volcanic rock. Although these don’t occur in the caves of South Africa, many East African sites like Olduvai Gorge do contain ancient layers of volcanic ash. Louis Leakey sent samples from Olduvai, and soon the results came out: The Bed I sites with Zinj and habilis were not 600,000 years old, as Louis had assumed. They were 1.75 million years old.

This new date changed the entire outlook of paleoanthropologists. The Olduvai tools and fossils were far older than any other human artifacts or fossils found anywhere in the world. But this was only the beginning. Louis and Mary had found fossils of extinct apes at sites much older than Olduvai. Somewhere in East Africa, there might be layers containing fossils of the original population that gave rise to all the later hominins, the roots of our family tree.

The quest for these earliest hominins became the major scientific story of human origins during the 1970s and early 1980s. American and French teams planned an expedition with Leakey into the Omo Valley of southern Ethiopia; when Louis’s health failed, his son Richard led the Kenya contingent. Omo produced many important fossils, including the earliest modern human skeletal remains, almost 200,000 years old, and earlier hominin remains, many more than two million years old. But no one found fossils to rival those at Olduvai Gorge.

Richard Leakey redirected his fieldwork efforts to the shores of Lake Turkana, in northern Kenya’s Rift Valley. There, throughout the 1970s and 1980s, he and his wife, Meave, led a skilled team of fossil hunters who became known as the “hominid gang”—the group I was fortunate enough to work with in 1989, during my first summer experience in Africa.

The early discoveries from Lake Turkana included remarkable fossils, including a skull then thought to be the earliest specimen of Homo from anywhere in the world. Scientists today identify it as the best example of the species Homo rudolfensis, a contemporary of habilis. In 1984, the hominid gang’s most accomplished fossil hunter, Kamoya Kimeu, found the first pieces of a skeleton that would eventually become the most complete Homo erectus yet discovered. Known as Turkana Boy, it is a young male, aged at approximately 1.5 million years old, with many humanlike body structures but key differences in the brain, skull, and teeth.

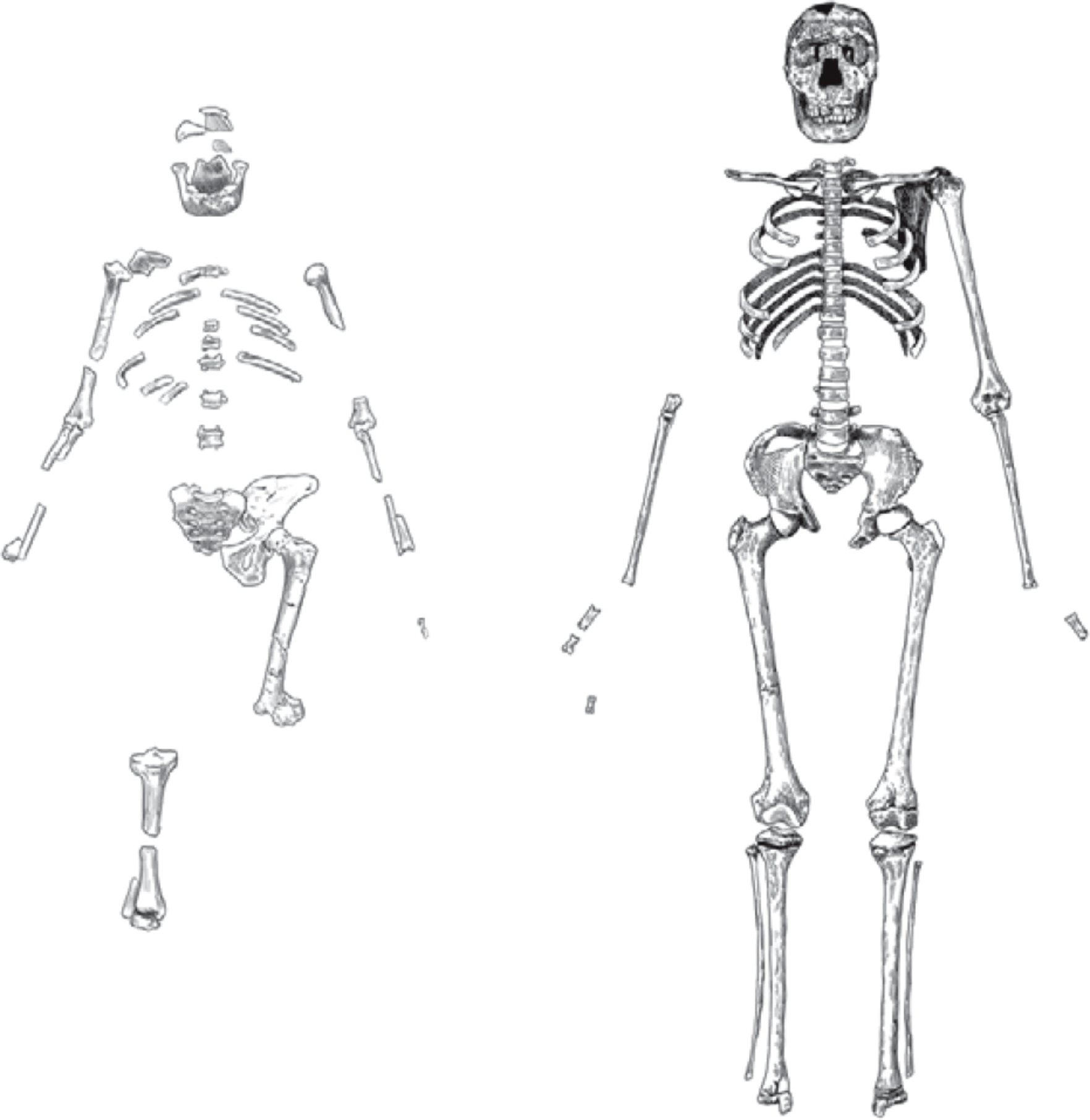

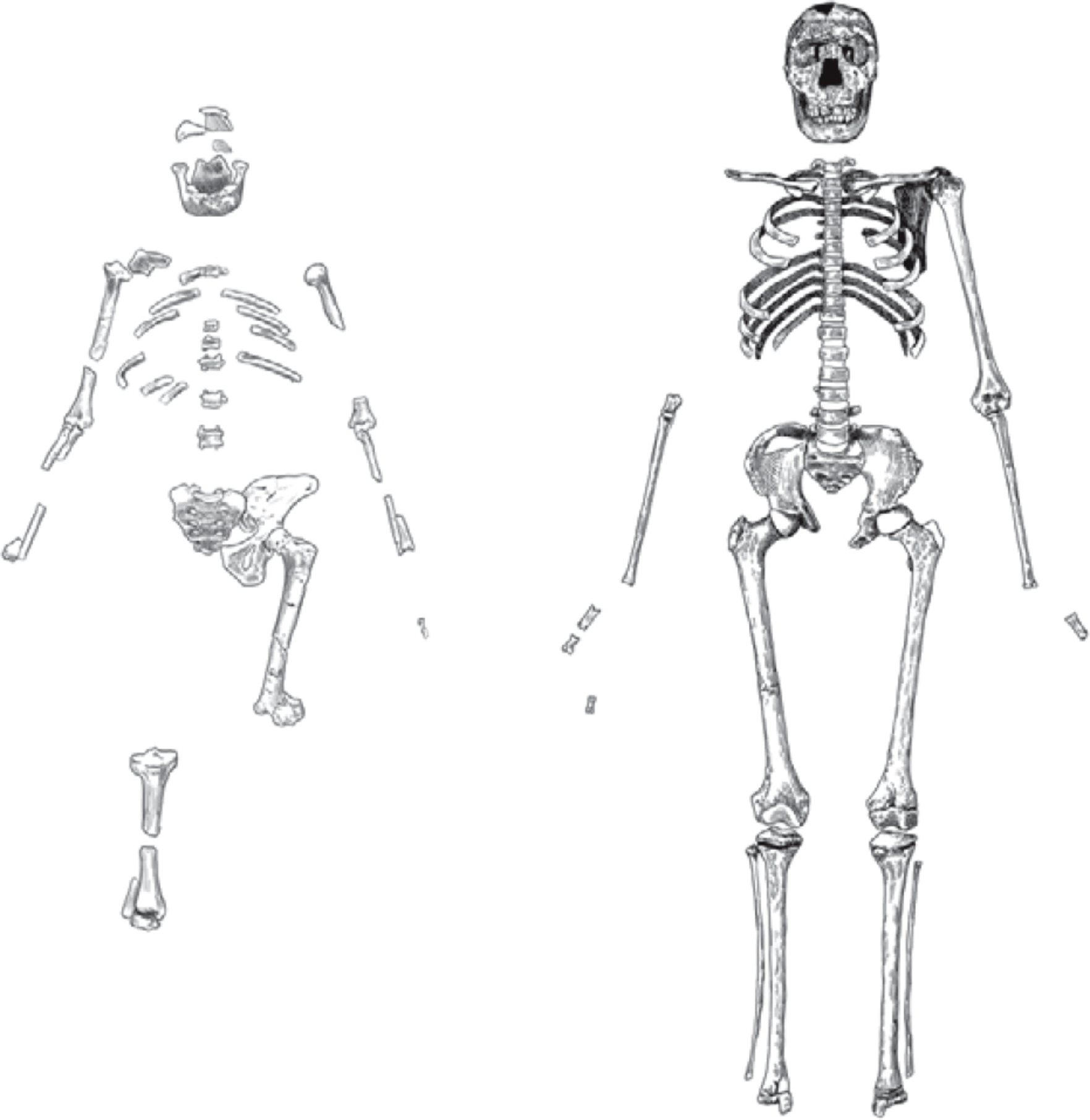

Meanwhile, in the early 1970s Donald Johanson, a brash young scientist from the United States, joined a field expedition at a site in Ethiopia called Hadar. The team found hominin fossils, including a partial skeleton soon to become the most famous in the world, nicknamed “Lucy.” Geological work dated Lucy and associated fossils back more than three million years.

At the same time, Mary Leakey continued to work in northern Tanzania, where she found hominin jawbones and teeth as old as 3.6 million years. Her team also uncovered many sets of fossil footprints made by a creature walking on two legs. Mary invited Tim White, a young American paleoanthropologist, to work on formal descriptions of the fossils. When White compared notes with Johanson, they developed the idea that the Tanzanian and Ethiopian fossils represented a single species, the earliest hominin then known. They named it Australopithecus afarensis.

The skeleton of Lucy (Australopithecus afarensis, left), compared with a Homo erectus skeleton (right)

The discoveries of the Leakeys, Don Johanson, and others constituted a second golden age of paleoanthropology. They shaped the science over the succeeding decades. These were the scientists whose work so thrilled me that I eagerly entered their field of study. They remained active during the years that I was a student and young professional, and they contributed profoundly to my own knowledge of human evolution. Their discoveries, and those of other scientists, have continued to expand the fossil record of human origins during the last 25 years, adding many more species to our family tree—some immediately accepted by most scientists in the field, others considered controversial. As I enrolled at Wits to take up paleoanthropology as my career, these scientists were predominant in a field that no longer looked to South Africa but instead looked to East Africa as the important setting for human origins.

A DEPICTION OF THE FAMILY TREE OF HOMININ SPECIES

Building this tree is a continuous effort of new fossil and genetic analyses, and the question marks indicate places where we cannot yet be sure of the order in which to place the branches. Please note: Not every species that has been proposed is included, especially in the lowest branches.