9

“Dad, I found a fossil!” It took me a few moments to recover from the shock of Matt’s discovery.

I had a tiny bit of cell phone reception—amazing for our remote location in the middle of the Cradle of Humankind—and I called the national representative of the South African Heritage Resources Agency. SAHRA protects fossil sites and manages permits for excavation. Despite poor reception, I managed to inform the permitting officer of the discovery, who gave me permission to take the fossil from the field. More than one paleoanthropologist has lost a fossil hominin to the elements by leaving it in the field, and we wanted to ensure this one was safe.

Back in my Jeep, Matthew turned to me as he sat in the passenger seat next to me and asked, “Daddy, were you angry at me for finding the fossil?”

I laughed. “Of course not, son—I am more thrilled about it than anything in my life! Why would you think I was angry?”

“Because you cursed when I showed it to you,” he said, in all seriousness.

I decided in the future, hominin discovery notwithstanding, I would have to watch my language.

Back at Wits, I filled out the permit application and called the landowners, setting up a meeting to show them the fossil. Enthusiastic about the find, they agreed to give their permission for the permit process.

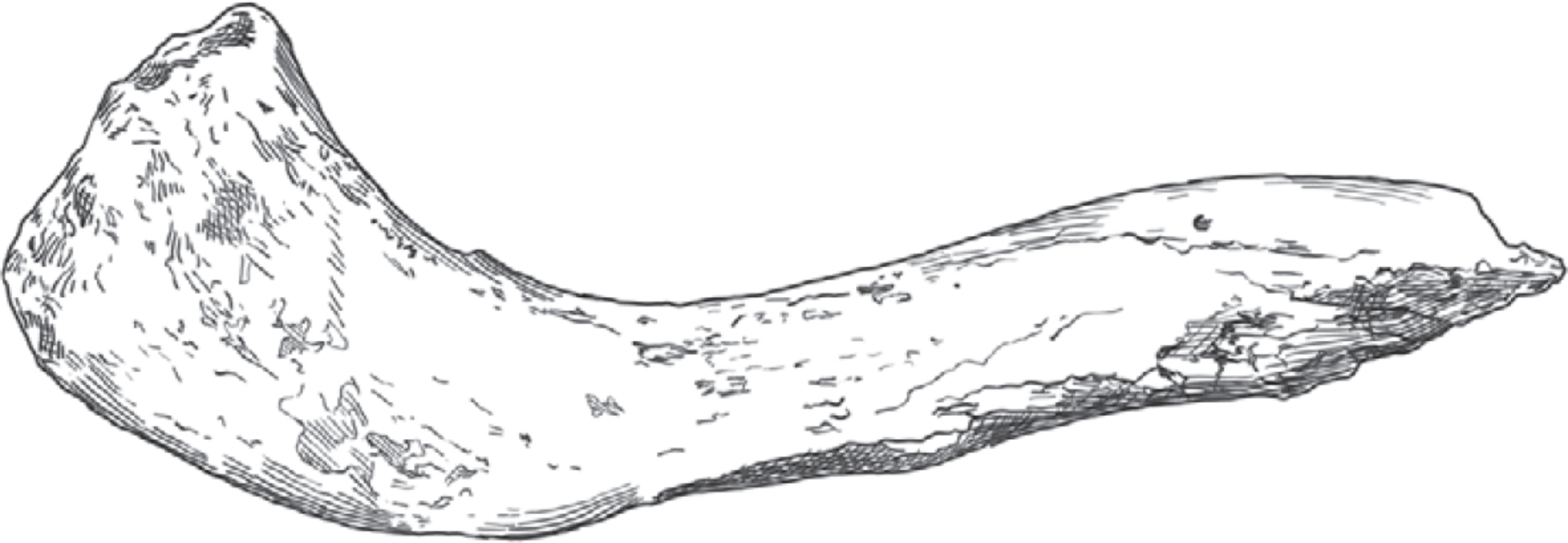

I sat back and looked at the rock. It was orange-brown in color, with the outline of a mandible, or jawbone, clearly visible, its canine tooth prominently sticking out. The tooth was pearl white, in beautiful condition. Its tip showed little sign of wear, indicating it was from a young individual who hadn’t spent years grinding the tooth down on a diet of wild foods. I could see other bones from the outside of the block, every one fairly easy to identify. The clavicle, or collarbone, sat in a horizontal position, about 10 centimeters long and orange in color. And there was the cross section of an ulna—forearm bone—and, near it, a rib fragment, both hominin. Maybe the whole shoulder girdle was inside this block?

The piece of clavicle that Matthew first noticed in the rock

But what species was this? I turned my attention back to the canine—out of all I could see, it was probably the most useful in answering that question. The tooth looked small, and the crown was simple—not the large, sail-shaped canine teeth from Sterkfontein that belonged to Australopithecus africanus. And it definitely didn’t look like the canine of a robust australopithecine. They tended to be still smaller than this one, with a squat shape.

I shook my head. All of these questions would have to wait for the fossils to be slowly prepared out of this block. That gave some chance of revealing more diagnostic parts, like premolars and molars, and perhaps parts of the cranium itself—the telltale part of the skull that cradled the brain.

Fossils embedded in hard breccia rock material are extracted only with immense skill and care. The process is called “preparation,” because the ideal is to prepare the fossil for study. Sometimes conserving the fossil is actually best accomplished by leaving some of the rock, not extracting the whole thing. For their work, the preparators use an “air scribe,” a metal device about the size of a large fountain pen, attached to a compressed air hose. The business end of the scribe is tungsten-tipped metal with a sharp, pencil-like point. As compressed air is injected into the scribe, the whole tip vibrates rapidly up and down, a few microns at each pulse. It is as if an ant had invented a jackhammer, throwing tiny shock waves down into the brittle breccia and chipping minute bits of rock away from the fossil bone. Technicians carry out the work under binocular microscopes, their extensive training guiding them as they regulate the speed of the vibration and bring the tip within microns of a fossil, never touching the fossil itself. It often takes more than two years of training on less precious fossils before a technician is ready to work on hominin material.

Preparation is not for the fainthearted. It takes tremendous patience, as a fossil may require thousands of hours of work to be revealed from the rock. It also takes a tolerance of the buzzing noise the scribe makes. The prep room at Wits, with many preparators working at once, sounds like inside a swarm of giant bees. Most find it grating. I, for one, love the noise, because to me it’s the sound of discovery.

I went to talk with Charlton Dube, a fossil preparator who worked for the Bernard Price Institute for Palaeontological Research (now called the Evolutionary Studies Institute). He was willing to work on the preparation of this hominin fossil, but he would have to work after hours. My available budget was meager, but I knew I could scrape together enough to pay for the overtime. We agreed on a strategy, starting with the mandible fragment and working around that area, and I left the block with him. Now to await the slow reveal—and the excavation permit.

A few days later I went over to Charlton’s prep station to see what he had uncovered. His work nearly took my breath away. There, emerging from the rock, was a beautiful mandible and several molars. Confirming the promise of this rock, the emerging jaw showed there should be other fossils within.

TWO WEEKS LATER, PERMIT in hand, I was back on the old lime miners’ trackway heading up to the site. For now, the site would be known by its number in the Wits system—U.W. 88, the 88th fossil site in our collections. I had put together the trip on the spur of the moment with Job, our postdoc, and more than a dozen people came up the hill behind us.

I smiled to myself, knowing why the trip had attracted such a large retinue. Almost never does a paleoanthropologist have a chance to find a fossil in the wild, so to speak. Now, we were walking up to a place where a nine-year-old had found a hominin fossil in under a minute and a half. How hard could it be? The mood was buoyant.

The old lime miners’ track was barely visible, overgrown by grass that was tall and dry in this late winter. As we walked, we were in the direct early morning sunlight, but the path curved up into the shade of a little patch of wild olive and white stinkwood trees. There, just to the right of the path, was a hole in the ground, maybe 10 feet deep and 15 feet across. The sides of this little pit were vertical in places, and we could see that the rock walls were mostly covered with a dark brown mix of soil and breccia. The trees clustered right around the pit. As one walked away, either uphill or down, the ground became a jagged surface of solid stone, foot-wide fingers of bedrock separated by ankle-deep fissures full of grass and brush. A few little animal trails snaked through the landscape. The old miners’ track was the one easy route to walk. Twenty meters or so downhill from the pit, across the miners’ track, was the lightning-struck tree where Matt had found the hominin block.

Our party scattered, turning over every loose rock, clambering down into the pit, intensely searching the area. Yet we found nothing definitive. We found fossils, but every fragment was hard to identify. Teeth would have been a sure giveaway, but we didn’t find a single one. There were no clear postcranial bones of hominins—nothing, that is, from any part of a body below the head. It looked like U.W. 88, like all the other sites in the region, was just full of antelope fossils. The nine-year-old’s discovery was looking less like luck and more like magic.

Around 10 in the morning, everyone stopped searching and sat down under a large white stinkwood tree for tea. I didn’t join in, frustrated with our lack of success. What if that block Matt found didn’t come from this pit at all? I wondered to myself. Matthew had found it 20 meters off the site, quite a distance. Maybe it came from one of the other caves up the hill and had fallen off a miners’ wagon as it passed by.

I walked over to the small pit, putting myself on the opposite side of the hole from where Matt had found the first fossil. How had that block gotten there, way across by the lightning-struck tree? From that pit in front of me, I tried to imagine the scene a hundred years ago or more as a tremendous blast of dynamite threw rock and rubble into the air. I imagined miners dropping down into the pit, filled with rubble, tossing rock out into small piles. There the rocks were, still around the pit where miners had thrown them. For the first time that morning, sunlight penetrated the branches overhead, and my eyes traced the back wall of the pit illuminated in the soft winter light. And then I realized it: I was staring straight at the head of a hominin humerus—the upper arm bone of an ancient ancestor.

I blinked in disbelief. I squinted to see better. But the circular head of a hominin humerus was unmistakable. I’d done my Ph.D. dissertation on the hominin shoulder—I knew that shape. We’d already searched that back wall several times that morning. But my eyes were not lying.

I said nothing.

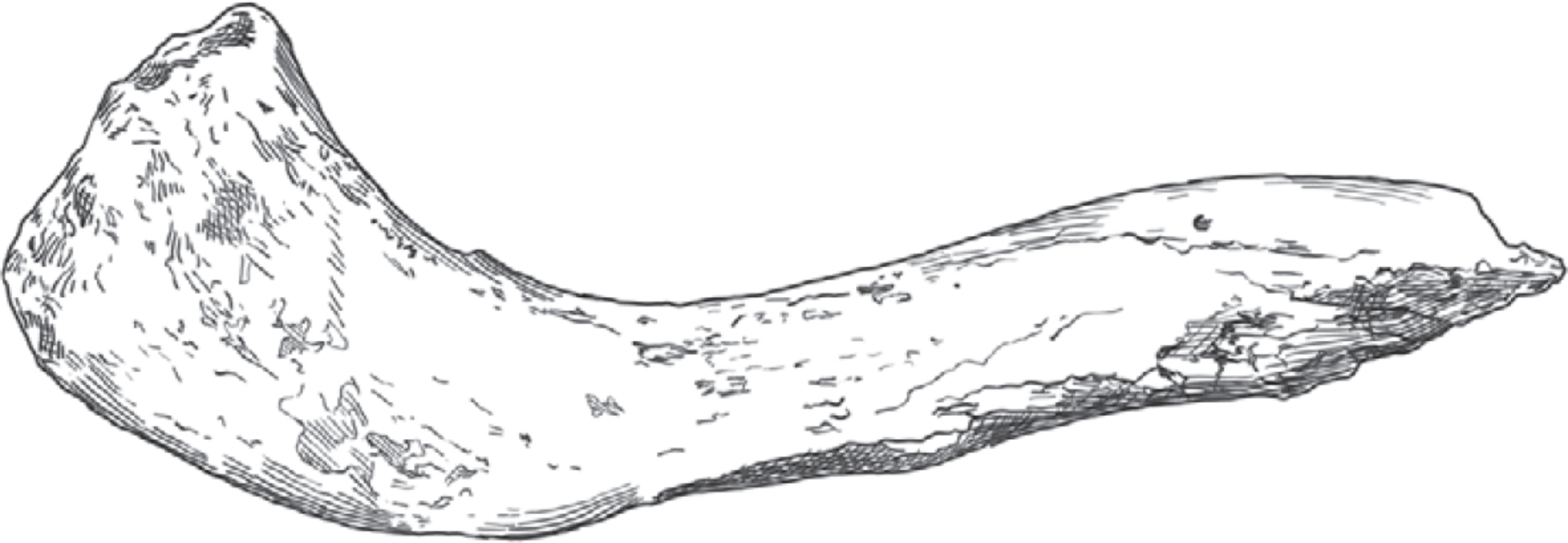

I carefully climbed down into the pit, keeping my eyes on that spot. As I reached the bottom, hearing conversations going on above me, I kept my attention on that bone. Getting closer, the picture became clearer: the head of a hominin humerus sticking perfectly out of the rock! A thin layer of lichen and moss covered it. And there, just below it, cut in cross section, clear as day, was the head and a long, thin section of the scapula—a shoulder blade! It must be an arm of the skeleton Matthew had found—an entire shoulder girdle.

I put my hand out to steady myself against the wall, a few centimeters to the right of the humerus and scapula. I could feel that this part of the wall was actually soft, just dirt. The lichen and moss had probably worked the calcium out of the breccia. As I put weight on my hand, two small rocks dislodged and trickled into my hand. But glancing into my palm, I realized that they were not rocks; they were teeth! Two hominin teeth had just fallen into my hand!

Nothing was keeping me quiet after that.

People crowded around. “Be careful!” I yelled. “They are falling out of the wall and we could be standing on them!” Everyone peered in disbelief at the humerus head, the scapula, and the two teeth I held in my hand.

As I said this, Luca Pollarolo, an Italian archaeologist from Wits, leaned over to pick up a loose rock at my feet.

“Stop!” I shouted, taking him by surprise.

I had seen something on the back of the rock as Luca tilted it upward. It was a hominin femur, clearly a thighbone from a juvenile because its two parts had not yet completely fused into one, indicating it was still growing when this individual died.

What a turn of fortune. Surely this had to be the skeleton of the child whose jaw Matthew had found two weeks before. There it was, I thought, a hominin skeleton in situ—in the exact place in the site where it must have lain for countless centuries.

Four more weeks would go by before I would realize my mistake.