Just outside Johannesburg, South Africa, the Cradle of Humankind, a UNESCO World Heritage site, contains numerous early hominin sites including Malapa, above, where the fossils of Australopithecus sediba were discovered. Credit 1

Lee Berger’s son, Matthew, then nine years old, spotted the first fossil embedded in a block of breccia, or composite rock material, at the Malapa site.

“Dad, I found a fossil!” he called out, the first step in a remarkable discovery. Credit 2

The fossil Matthew Berger found at Malapa, a small white intrusion in the breccia rock, turned out to be the clavicle, or shoulder bone, of an ancient hominin. Credit 3

Lee Berger and his son, Matthew, together with their Rhodesian ridgeback, Tau, survey the landscape in which they found fossils of Australopithecus sediba in 2008. Credit 4

At Malapa, a pit several meters deep is all that remains of the ancient cave where fossils formed. Blocks of breccia that included pieces of two skeletons were blasted out, and the rest of the skeletons were found in their original locations, indicated here. Credit 5

With Matthew Berger as he made the first discovery were Job Kibii, at left, a postdoctoral researcher in paleoanthropology at the University of the Witwatersrand, and Lee Berger, Matthew’s dad—here proudly smiling from the Malapa site. Credit 6

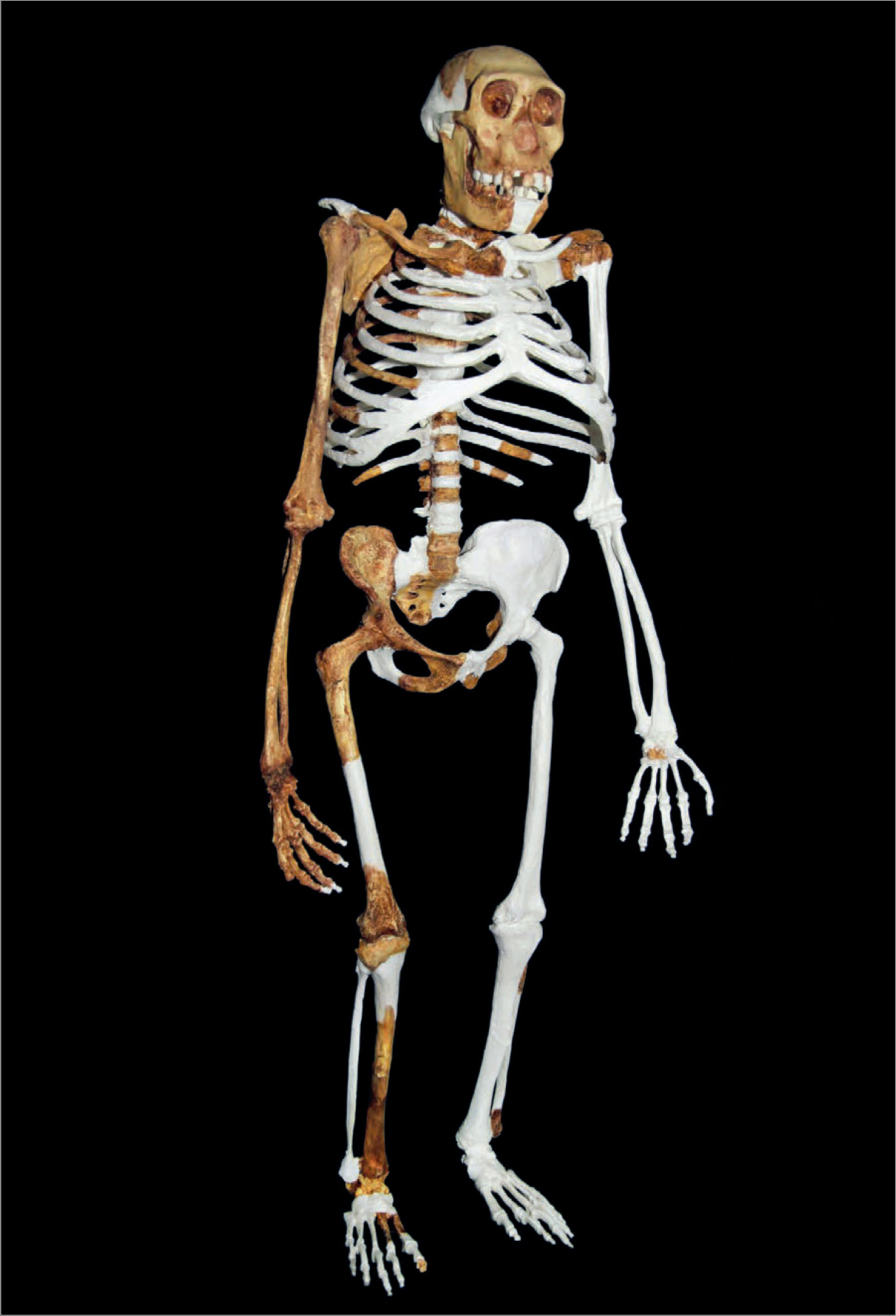

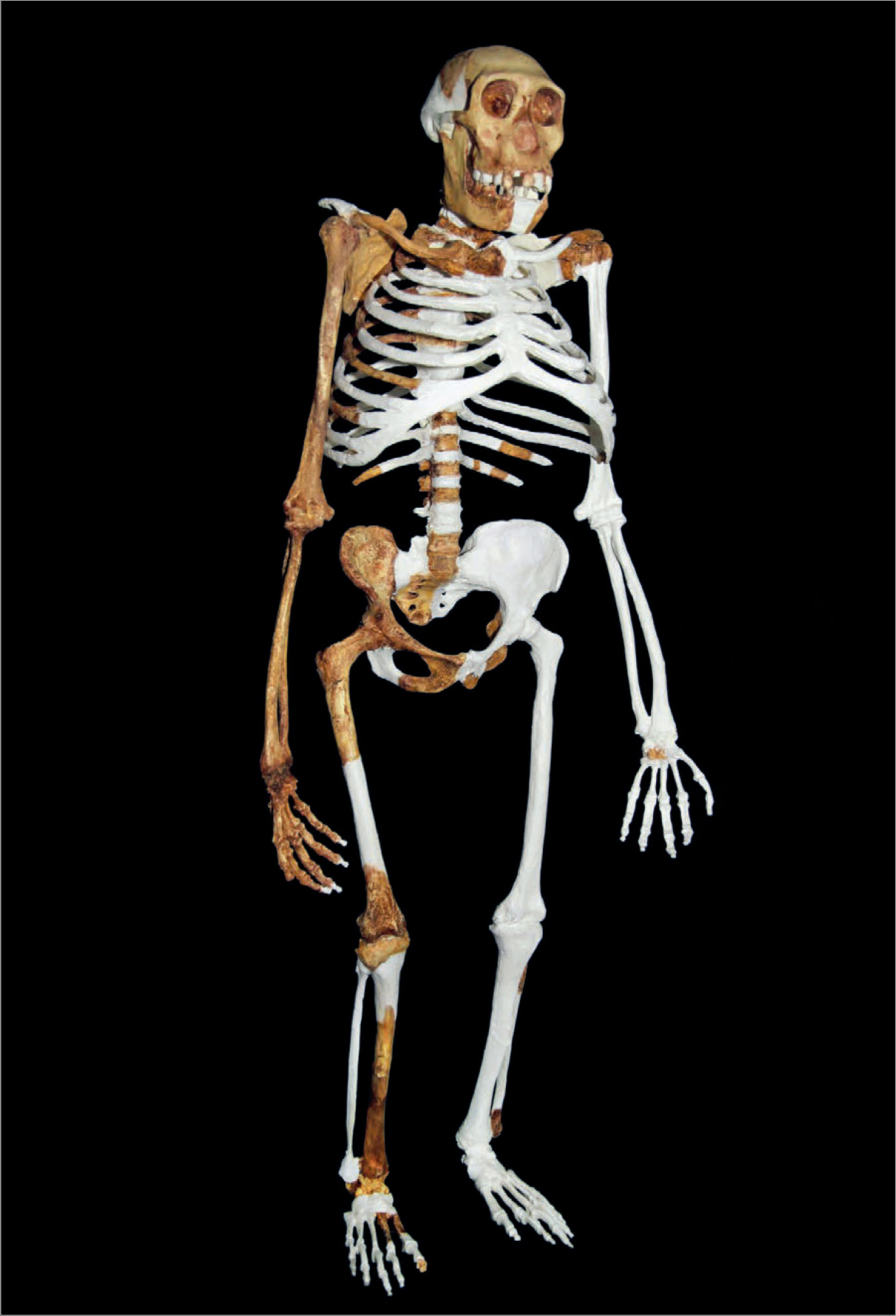

As the Malapa finds were pieced together, Berger and his team found that they had the better part of two complete skeletons representing Australopithecus sediba, an adult female, at left, labeled MH2 (for “Malapa Hominid 2”), and a child, MH1. Credit 7

Particularly remarkable among the Malapa finds was the skull of MH1. Rarely do researchers come upon an intact early hominin skull, and this one became a crucial key to understanding the new species. Credit 8

First viewed via a CT scan, the fossil skull of MH1 required delicate work to extract it from the surrounding rock. Here Lee Berger watches as preparator Pepson Makanela uses an air scribe, a precise compressed air tool, to clean around the teeth. Credit 9

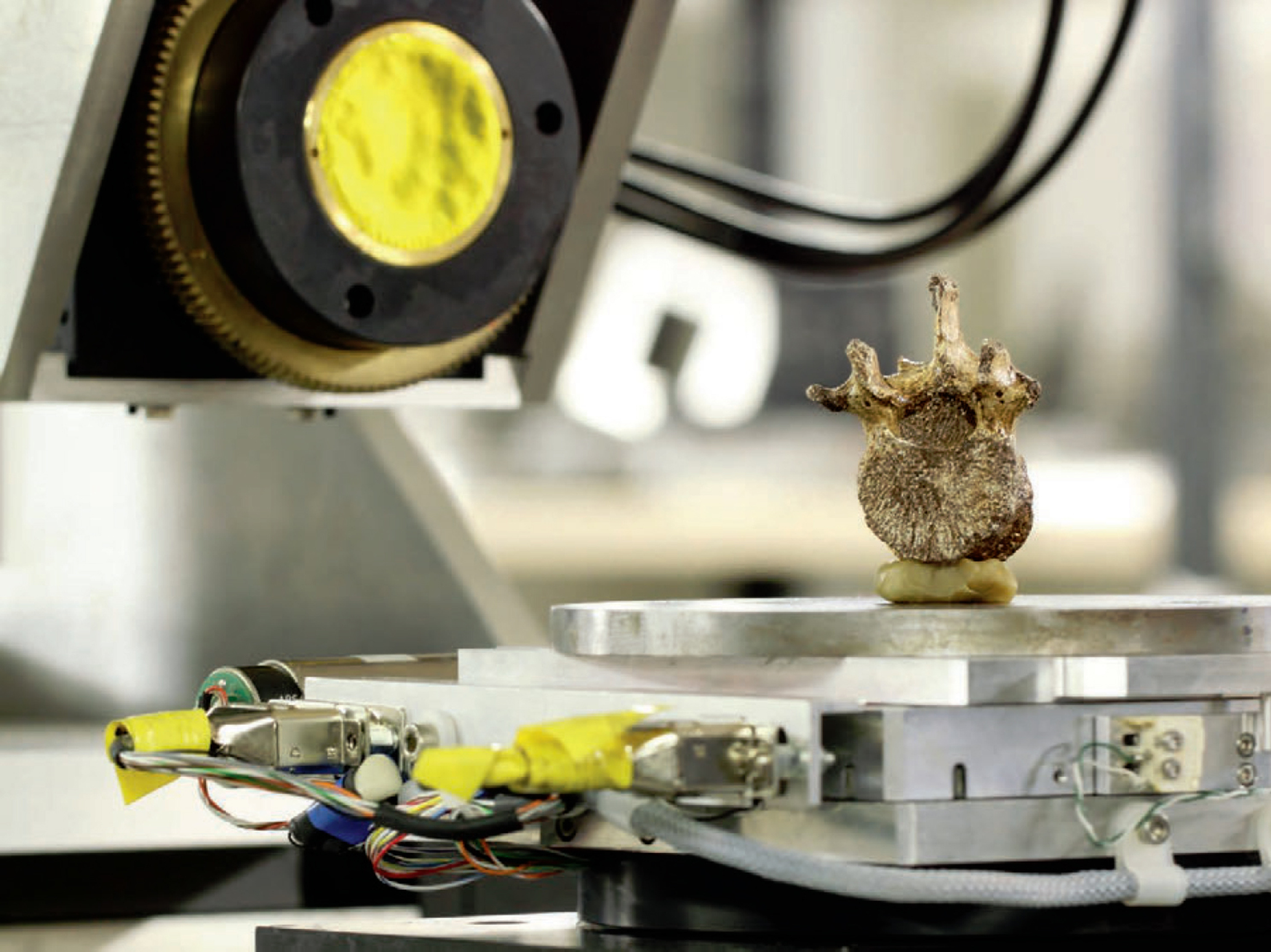

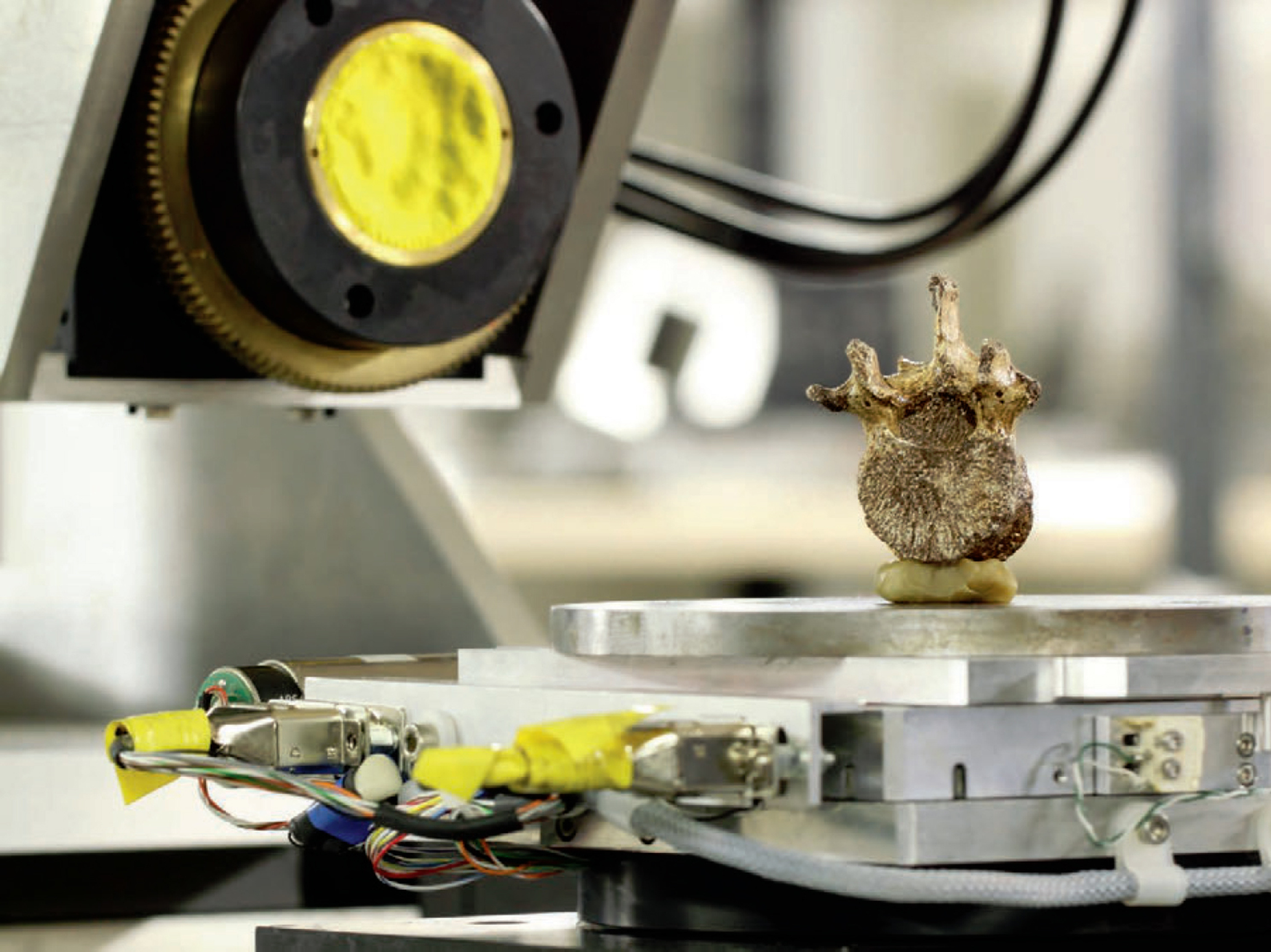

High-tech meets prehistory: A vertebra from Malapa is set up for scanning to examine its internal details. One of the Malapa vertebrae has yielded the earliest evidence of a benign tumor in the hominin fossil record. Credit 10

Using synchrotron radiation, an advanced type of x-ray analysis, researchers have been exploring the nature of the MH1 skull without damaging it. Credit 11

Basing it on the fossils found at Malapa, Peter Schmid of the University of Zurich, Switzerland, prepared this reconstruction of the Australopithecus sediba skeleton. The brown sections reflect the fossil bones actually found. Credit 12

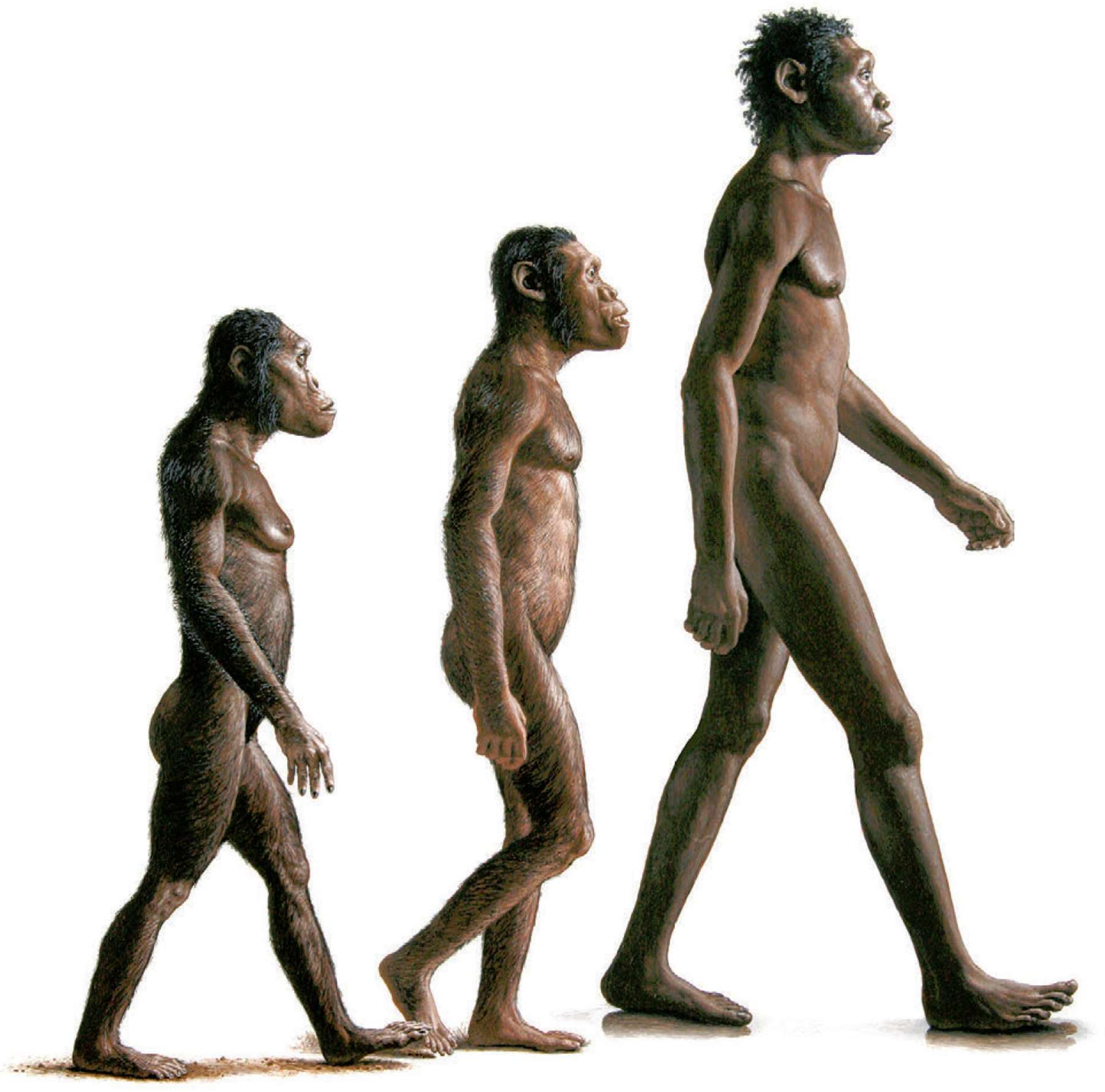

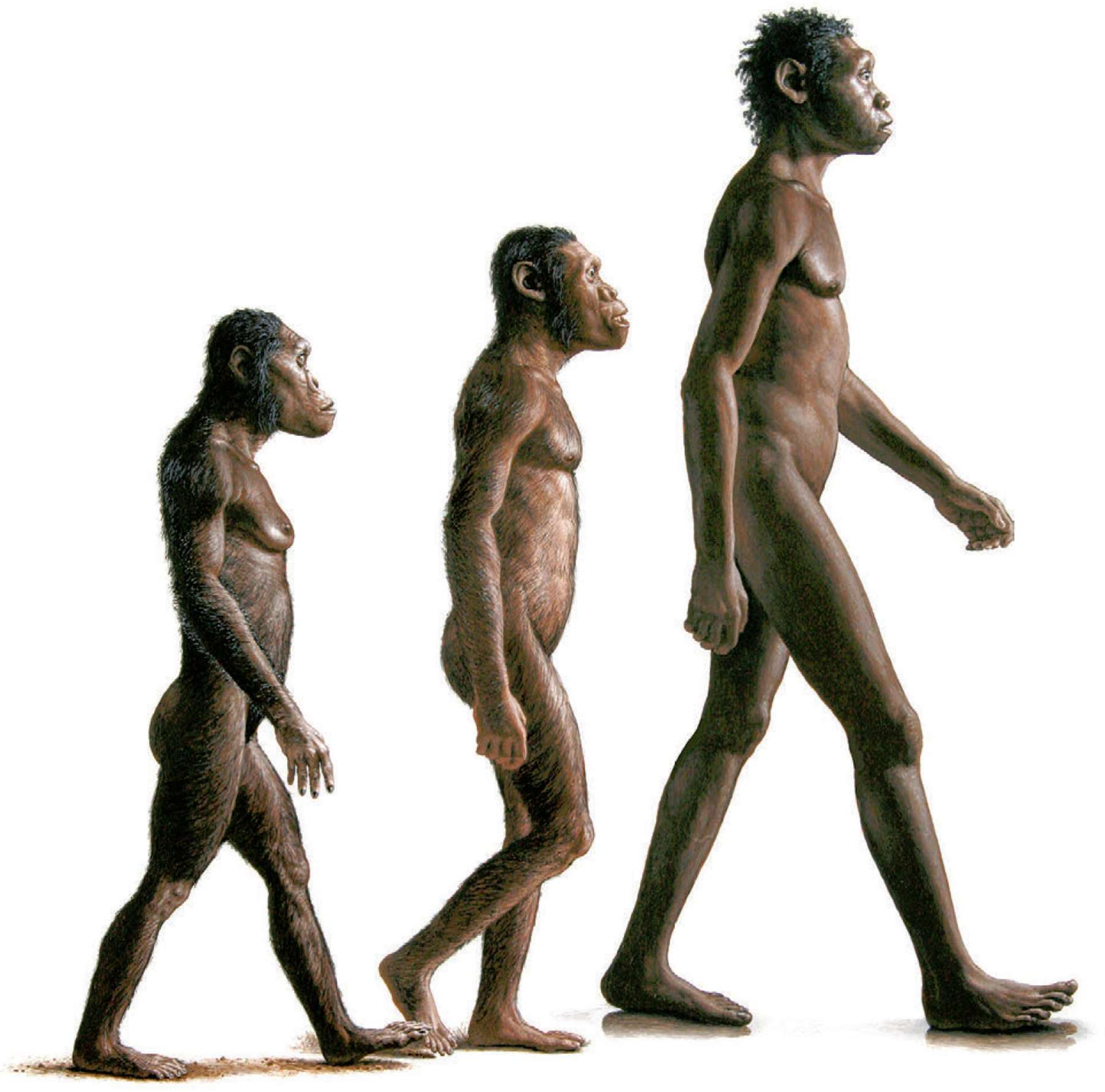

This artist’s interpretation illustrates the relative sizes and proportions of three key hominins, left to right: Lucy (Australopithecus afarensis), Malapa’s Australopithecus sediba, and the Turkana Boy (Homo erectus). Credit 13

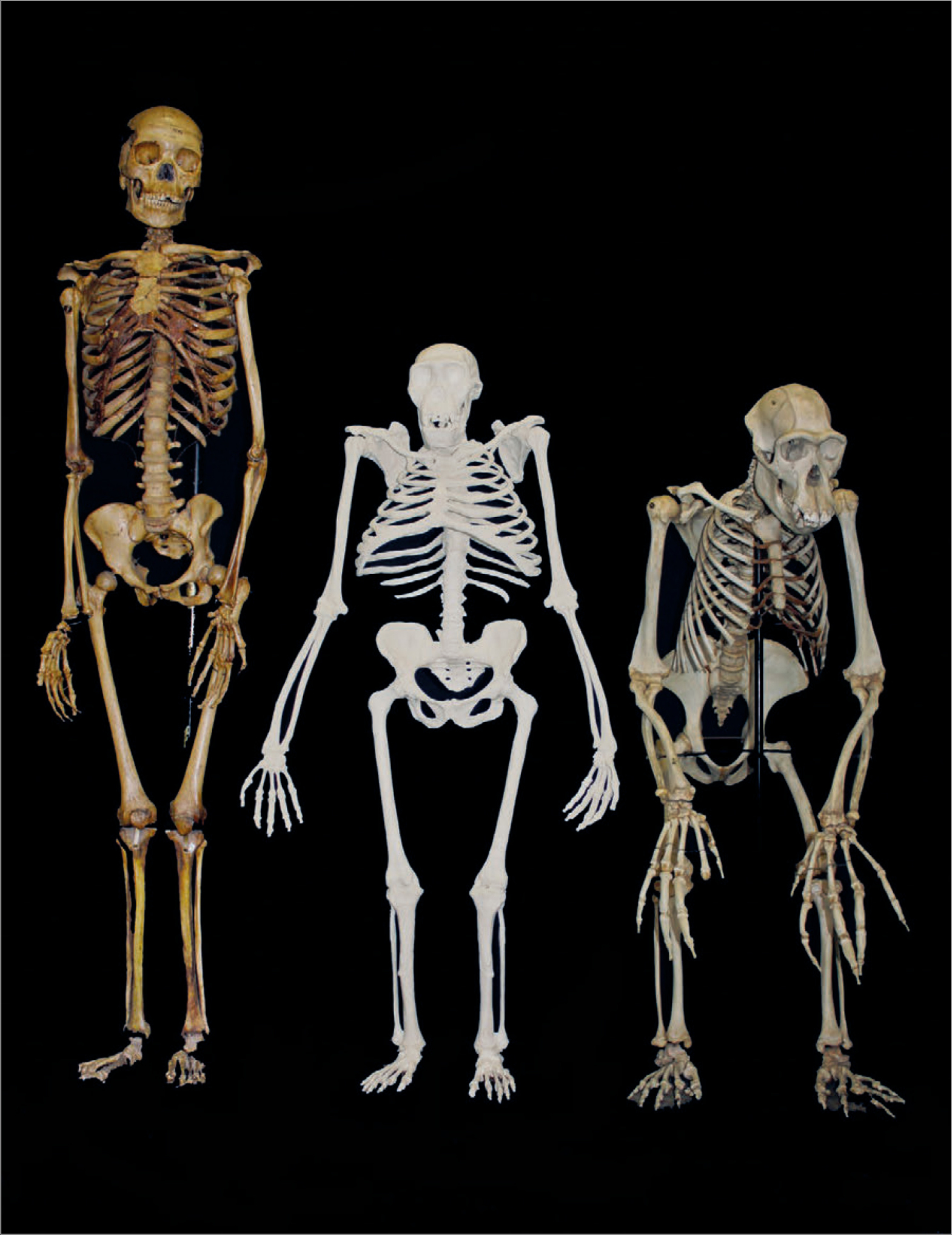

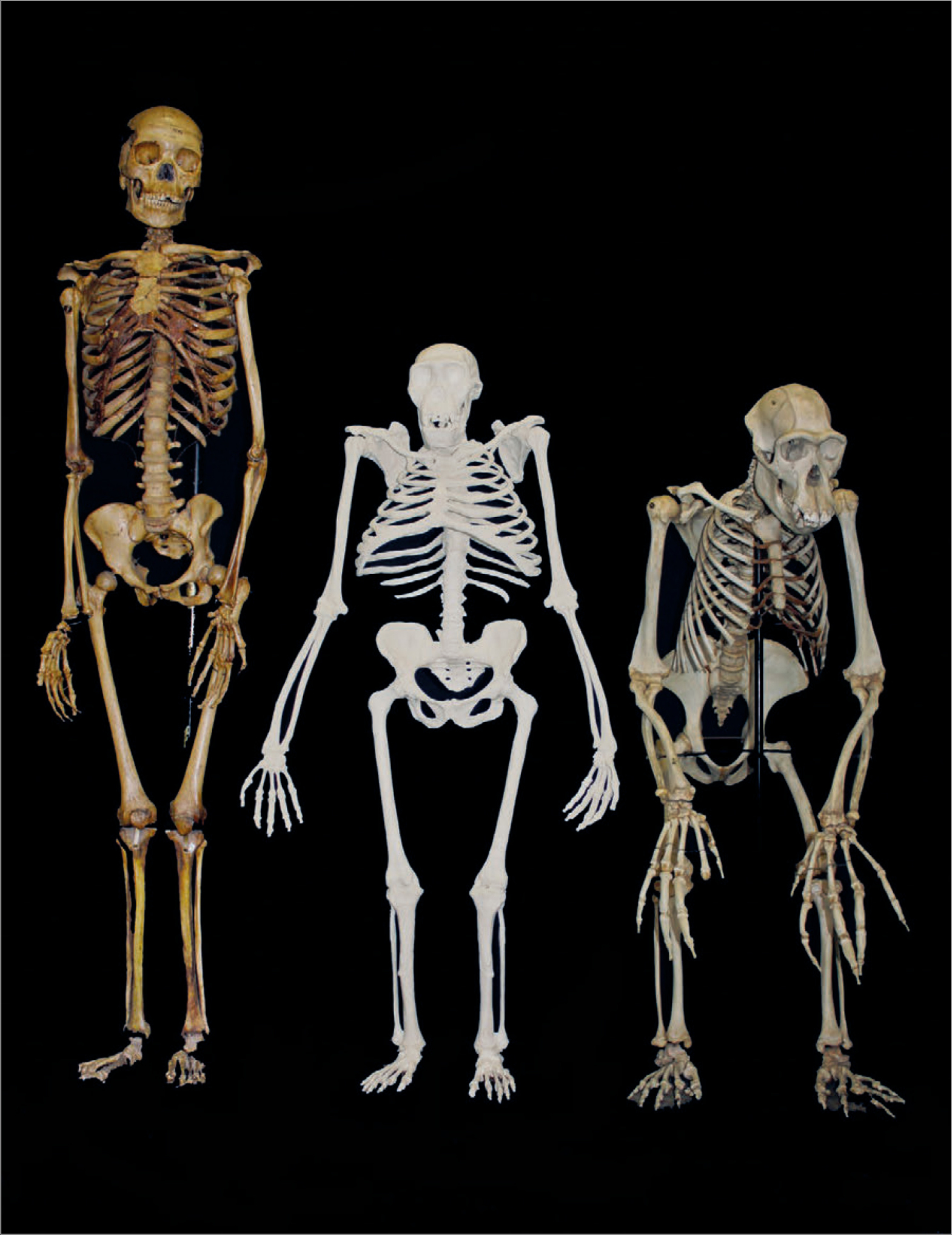

Comparative skeletons of, left to right, a modern human, Australopithecus sediba, and a modern chimpanzee show that although A. sediba walked upright like humans, it also shared many features with modern and ancient apes. Credit 14

Thoroughly extracted from the rock that contained it, the skull of MH1 allows us to look right into the face of Australopithecus sediba. Credit 15

Beginning with the excavated skull and building up musculature and soft tissue around it, artist John Gurche reconstructed this life model of A. sediba. Credit 16

How did the bones end up underground at Malapa? One explanation may be that the site represented a prehistoric death trap into which individuals fell and from which they could not escape, as portrayed in this artist’s interpretation. Credit 17