Sioux Falls, South Dakota

We arrived in Sioux Falls on our wedding anniversary. That evening, we headed from our motel to the nearby Granite City brewery: it was an introduction to the reality that we would be able to find brewpubs almost every place we went. (Granite City started in St. Cloud, Minnesota, and was at that time spreading across the Plains States.)

Our anniversary, on the summer solstice in June, is the longest day of the year. In the long, late night of the northern plains on June 21, we watched the sun spread a slanting light over the city’s bike path and talked with a group of young women who were out on the town on some sort of celebration. It turned out they were all nursing students, and all from smaller cities around the plains. Did they like Sioux Falls? we asked. Oh yes, they began telling us in detail. It was growing. It was friendly. (Proving their point, they bought us beers when they learned that it was our anniversary.) It was big enough to have everything—especially with a growing medical community—and small enough to be approachable and easy. “It’s a big small town,” one of them said—the first but not the last time we heard that.

The excitement of the young nurses about the opportunities in the city, and their emphasis on the just-rightness of Sioux Falls, turned out to be no accident. The profound impact of the local circumstances—the farm economy, its position as capital of this part of the prairie, its central location within the continent—were ingredients in the economic strategy that made Sioux Falls work.

Every city that is trendy or successful in some way attracts people from someplace else. The biggest, hottest international magnet cities—Los Angeles and San Francisco, New York and Washington, D.C., Boston and Chicago and Miami and Seattle and whatever you’d add to the list—draw people from around the country and the world. If someone from South Dakota shows up at a research lab in Boston or a tech team in the Bay Area or a TV show in Los Angeles, the standard coastal narrative would be that the person had “made it” out of the heartland and into the big time.

The dominant tone we heard in Sioux Falls was of people who feel that they have “made it” precisely by getting to the state’s biggest city from the farms or tiny hamlets where they grew up. The big-box malls all around Sioux Falls are a disappointingly familiar part of its look, versus the more homegrown look of its restored and revived downtown. But those malls also symbolize the city’s role in the region, which, in turn, gives so many people there a sense of being in the right place at the right time—of having come to a place, rather than just having left wherever they were from. Many people we met, like the nurses that first night, talked about Sioux Falls as occupying a sweet spot: big enough to offer most of what is attractive about very large cities (shopping, medical care, entertainment, and an increasingly rich food-and-drink life) but small enough to be manageable, inexpensive, and—something we often heard—“safe.”

Our first impression of Sioux Falls was dominated by three great features. One was the falls themselves, on the Big Sioux River. They are in the center of town, and a dozen years ago they had been crime-ridden and graffiti-covered. As part of a civic cleanup program, they had been surrounded by a polished-seeming Falls Park—an attraction for tourists, a destination for local families. The park’s improvement came in parallel with a similar large civic effort: the twenty-mile bike and walking course that circles the entire town. We didn’t realize it at the time, but the falls and the trail were markers for something we’d encounter almost every place we went: restoration or revival of civic attractions, like the falls, and creation of bike and walking paths. Deb eventually formulated a law: the mark of a successful city is having a river walk, whether or not there is a river.

The second prominent feature, dominating a hill overlooking the falls and the adjoining part of the bike path, is the state penitentiary. We learned that it was the subject of a hoary local joke. Back in the 1880s, when the Dakota Territory was preparing to become two states, the prospective South Dakota state government offered what was then (and still is now) its largest city, Sioux Falls, a choice: Would it prefer to be the home of the state university? Or of the state penitentiary? The joke was that the penitentiary offered steadier work for locals, so that is what they took. The University of South Dakota wound up in the much smaller town of Vermillion, but Sioux Falls now has an assortment of public and private universities.

The third major feature, the most evocative of all, is the giant downtown abattoir generally known as John Morrell’s, where thousands of pigs go to their deaths each day. In many parts of the United States, you might complain that it’s hard to “see” the economy anymore. There are too many indistinguishable office blocks, too few old-economy structures where “real” work is done. In downtown Sioux Falls, where the slaughterhouse is an unavoidable visual and aromatic reminder of the realities of the modern food chain—and where it has a distinct social significance, as well—you would never say that. In the century-plus since John Morrell opened the slaughterhouse, in 1909, it has been an arena for wave after wave of ethnic and economic change in this part of America. Eastern Europeans and Germans worked for Morrell during the pre–World War I era of mass immigration. As a high-wage unionized employer for half a century after that war, despite the physical and psychological hardships of the jobs, Morrell was part of the road to the middle class for people in the area. People we met at the newspaper, the universities, the city governments, the banks had family stories that began with versions of “We came to town when my dad got a job with Morrell’s.” By the 1980s, it was a center of bitter labor strife, which led to a strike and the breaking of the union.

Now it symbolizes two aspects of the global connection of even the most removed-seeming parts of the American topography. One is its workforce, which has become part of the area’s refugee fabric. From Somalia, from Sudan, from the Congo, from Burma and Nepal, the latest round of immigrants are working in this plant. The other is its ownership. In the 1990s, the Morrell company sold to Smithfield, which, in turn, was sold in 2013 to the Chinese firm Shuanghui. As we’d known from our previous years in China, Shuanghui and other higher-end food companies were in a desperate race to demonstrate to customers that they offered safer, less adulterated products, ones that met international standards.

Thus from the slaughterhouse in the center of town, in this corner of Plains States America, you had a little parable for globalized connections, regardless of changing political sentiments. Every morning, pigs that have spent all but the final days of their lives in Iowa, which has more permissive legislation on large-scale pig-rearing, cross the Big Sioux River into South Dakota and proceed toward their fate. In the slaughterhouse, workers—mainly refugees who have come from every corner of the world—put the pigs to death and convert them into meat, and then a Chinese company, relying on the United States’ reputation for higher food-safety standards, ships much of the meat to customers who are rapidly moving up the protein chain in China.

There was one other significant aspect of Sioux Falls’ appearance, which took us a while to notice but whose significance eventually became plain. That is the city’s sprawl—taken for granted as part of the automobile-era American landscape, but with additional meaning for Sioux Falls and places like it.

Some cities look smaller than they actually are. When living in Shanghai, we tried to make sense of statistics showing that our immediate walking-and-shopping neighborhood had a population of more than one million, or maybe two. Sioux Falls is the reverse. The official population is above or below two hundred thousand, depending on how much of the surrounding area you take in, but the sprawl and physical extent is that of a much larger place. If the footprint of Sioux Falls were laid down anywhere in China, you’d expect a population at least twenty times as great. We later learned what reasons, apart from standard-issue sprawl, accounted for the city’s footprint.

An improbable part of the region’s economic base is its role as a financial center. The next time you receive a credit-card statement, check the address. Odds are that your payment is headed to Sioux Falls. That is the result of an effort by state leaders in the late 1970s, when they used the state’s heart-of-the-country location as part of a winning argument that Citibank and other major credit-card companies should move their processing centers there from high-cost locations in New York. At the time, Nevada, Delaware, Missouri, and several other states, including South Dakota, were in a race to the bottom to relax their usury laws, so that financial companies headquartered there could charge whatever interest rates they wanted. But in itself that wasn’t enough to make Sioux Falls plausible as a next home for operations historically based on the East Coast. “And that’s where Benjamin Franklin and Wernher von Braun come in,” as Robert E. Wright, an economics professor at Augustana University in Sioux Falls, wrote in “Wall Street on the Prairie,” an online history of Citibank’s decision.

The Benjamin Franklin part of the decision involved the U.S. Postal Service, of which Franklin was the first postmaster general. For reasons involving the great efficiency of Sioux Falls’ transportation system and the congestion of its counterparts in the East, South Dakota officials argued that a payment mailed in from one of the five New York boroughs would reach Citibank more quickly if it had an address in South Dakota than if that same check was sent right to its headquarters in New York. “That sounds incredible and is almost certainly apocryphal marketing hype,” Wright wrote, “but what mattered is that Citibank officials believed that payments and other correspondence sent from most places in the country would reach Sioux Falls before they would hit New York’s financial district.”

The Wernher von Braun part of the equation was shorthand for the Cold War–era space systems, military and civilian, that the United States deployed with help from scientists who had once worked for the Nazis, like von Braun. These included strategic bomber bases and ICBM sites in the Dakotas—which, in turn, meant an advanced telephone and, eventually, Internet communication system that happened to link Sioux Falls with the outside world in a reliable and very high-speed way. In those days when “long-distance” calls were still expensive—either for the customers or for the company offering a 1-800 system to absorb the cost—it was cheaper, on average, for callers from around the country to phone into relatively central Sioux Falls than to call New York. Beyond that, the accent of Sioux Falls residents sounded “normal,” rather than regional, to callers from most other states. “People could understand us!” Wright said, when I met him at Augustana. “And on the phone, we were nice. There’s a culture of education and work here.”

The city willed itself into a role as a back-office financial center. By 1982, one-third of all the mail going through its very efficient post office was for Citibank. By the time we visited, a generation later, 10 percent of the local workforce held finance-related jobs, roughly twice the national average.

Sioux Falls also created an advantage in the realm of high tech, with two facilities that, in their fields, are now world-famous.

One of them, Raven Industries, ended up here through a combination of effort and happenstance. During the all-out militarization of the U.S. economy during World War II, a time in which Henry Ford’s car-making company became one of the world’s largest producers of airplanes, General Mills, of Minnesota, the same company best known now for breakfast cereals, also served as a military contractor. After the war, General Mills set up the Aeronautical Research Division, which specialized in high-altitude balloons. In those pre-satellite days, balloons were uniquely valuable for carrying sensors and surveillance cameras. By the mid-1950s, four General Mills engineers were ready to leave and start a balloon company of their own. For reasons ranging from airport congestion (airports in the Twin Cities were very crowded; Joe Foss Field, in Sioux Falls, was more welcoming) to prevailing-wind patterns, they decided to start their new company in Sioux Falls.

The company has become dominant in a number of tech-intensive fields, all of them involving advanced balloons. First is Raven’s Aerostat line: great big surveillance balloons used by the Customs Service, the U.S. military overseas, and similar customers. We went to a hangar at a Raven location, in the middle of a cornfield ten miles north of the city, to see some of these huge devices.

Another part of the balloon-tech division makes the cartoon-character balloons familiar from Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parades in New York. In the summer of 2013, five months before that year’s parade, Deb and I enjoyed the frisson of seeing the then-secret designs on the hangar floor. And the third high-tech balloon effort was providing the launch vehicles for Google’s Project Loon—an ambitious plan of that era to provide very low-cost “Internet for everyone” to underserved parts of the world, via a network of high-altitude balloons. Raven was making the balloons—sixty feet tall, designed to fly at 66,000 feet—there in Sioux Falls and preparing them for launch.

Raven has also been developing the agricultural version of self-driving cars. These involve GPS guidance systems for farming vehicles so tall, wide, and complex that the word “tractor” seems disrespectful. By whatever name—combine, behemoth—these have been part of a digitized revolution in farming. GPS guidance allows farmers to plow furrows longer and straighter than had ever before been possible; to apply fertilizer to the exact points where seeds have been sown; and in countless other ways to speed the age of “precision agriculture.”

Not long after Raven’s arrival, Sioux Falls also became the home site of an even more broadly significant aerial-technology company. In the late 1960s, the Pentagon, NASA, and the CIA were looking for a safe central location for the rapidly increasing flow of satellite imagery of the earth. South Dakota’s senator Karl Mundt worked with Sioux Falls officials to demonstrate that their area was ideally situated to receive data from satellites as they passed over the United States. In the early 1970s, they opened the Earth Resources Observation and Science Center, or EROS, in a cornfield just north of Sioux Falls. Now it is a repository of more digital images of the earth—military, civilian, environmental, cartographic—than any other. Much of what you have seen on Google Earth originates from a master file at EROS, as did most of the graphics used in international climate talks. Because of EROS, hundreds of scientists have come from around the world to work in Sioux Falls.

We spent most of a day touring EROS, seeing its huge antennas, onto which satellites download their data, and the sequence of historic photos that show the loss of tree cover in the Amazon (“Since the Brazilian government began using our photos, they’ve slowed the rate of deforestation!” Tom Holm, chief of the policy and communication office at EROS, told us); urban growth in China (“You can see how Beijing emptied out during the Cultural Revolution—and the development since then”); and the changing size of lakes and robustness of wheat fields in the Great Plains States during wet years and dry.

“I have the best possible combination,” Holm told us. He had grown up near Sioux Falls, done his undergraduate work at South Dakota State nearby and spent a summer as an intern at EROS, and then headed off for graduate school before returning. “I work in one of the most exciting places on earth, and I am home.”

There’s more in the town: a significant health-care establishment, part of it funded by a local credit-card entrepreneur made good named Denny Sanford. Diverse community colleges and universities. A start-up tech sector and, for most of the years since 2013, the lowest unemployment rate in the country.

The Sioux Falls area has its severe problems as well. We saw signs of the opioid crisis there. The state’s numerous tribal reservations are mainly far to the west, but the chronic economic and health problems of many of their residents affect life statewide. Floods, drought, climate shift, and volatile world markets affect the farming industry; and on down the list. But while the outside world might easily have assumed these and a score of other challenges, how much was going on in this part of inland America would, we thought, come as a surprise.

We weren’t surprised to find that Sioux Falls had become the move-to town for aspiring residents of many of South Dakota’s rural towns. What we hadn’t expected was the great number of people in another group, those who were instantly distinguishable from South Dakotans of German and Scandinavian heritage. These are the foreigners, of so many different colors and ethnic groups.

Beginning in the 1970s Sioux Falls welcomed wave after wave of refugees. The city is well known in the refugee and migrant community for having a strong supportive system. The population is large and diverse. Take the schools as a proxy. Nearly 10 percent of the students in Sioux Falls public schools are designated as ELL (English-language learner) students. They are native speakers of some sixty different languages. Sixty. Can you even name sixty languages?

When the Sioux Falls public schools opened their doors in 2013, the biggest single group of these students, about one-third of the total (according to school district figures), were the 700 Spanish speakers, many of whom arrived in migrant worker families. As for the other two-thirds, when we visited, there were 259 Nepali speakers, 135 who spoke Arabic, 129 Swahili, 101 Somali, 93 Amharic, 84 Tigrinya (a Semitic language from the Horn of Africa), and 77 French. A very long tail of other languages included many I’ve never heard of, and I have been studying languages and linguistics all my life. Mai Mai had 27 speakers in the city, Nuer had 7, and then there were Grebo, Lingala—the list goes on.

The Jane Addams elementary school is an immersion school for the newly arrived non-English-speaking children. The students can stay in the program for up to two years before integrating into mainstream schools. It is part of a strong, textured Sioux Falls infrastructure of support, from health services to jobs to churches to housing to sports.

The school programs start in the classroom and extend to tutoring, summer school, free lunches, and bus passes. They also look to whole-family success. Home-to-school liaisons do things like help schedule parent-teacher conferences and round up translators. Sometimes, translation involves the children’s game of telephone, where speakers pass on a message from one language to the next and the next, and then back again. Such details are fundamental to keeping the entire system working.

The refugees and those who work with them told me about some of the cultural differences:

Gender: Many of the immigrants come from countries and cultures where education for girls is an afterthought. Arriving in the States, girls lag far behind in their school experience or may even be starting school for the first time, no matter what their age. The academic and social cost to the girls is obvious. Boys often have another advantage. In a word: soccer. Being a good athlete translates into many advantages, starting with positive attention from teammates, classmates, coaches, and fans.

Birthdays: Many refugee kids share a January 1 birthday. Coincidence? A mother of ten from one refugee family told me that if she, instead of her husband, had been the one to answer questions during the blur of the final entry paperwork, she would have provided the proper birth dates. The default was January 1.

Lunch: Many students told me that because of their sketchy schooling in refugee camps and their native countries or just being on the move for years, they aren’t competitive enough academically to get into the classes with the “American kids,” as they call them. That leaves lunch as a potential hangout time to mix and mingle. They also said that while friendships at least have a chance to start at lunch, they usually also end at lunch. After-school jobs, transportation issues, and the preferences of some families to keep their children close can complicate the after-school social scenes for newly arrived kids. I heard from coaches who would personally drive some of their immigrant athletes to and from practices, so they could be part of the team.

Being Muslim: Administrators noticed that it seemed particularly cruel for fasting students to sit idly in the cafeteria during Ramadan while everyone else was eating. To address that, the school provided a place for those students to spend that time.

The basics: Where do you start acculturation with the ocean-deep discrepancies among the children? In refugee-rich Burlington, Vermont, one school’s population includes the daughter of the principal and a little boy whose life experience is so raw that he pees in the corner of the classroom because he can’t imagine a toilet in a restroom.

Reaching for dreams: A refugee from Darfur, a high school sophomore, told me with pride that she had joined Junior ROTC at her school. She said she liked the history lessons and the activities the program provided. A big disappointment, however, was not being allowed to wear her hijab along with her ROTC uniform to school on Dress Day. She would have to choose.

It was beyond me, from my adult perspective, that this girl’s preoccupying problem at sixteen years old was her apparel conflict. She had been through more tragedy and miracle by the time she was six years old than most of us will experience in a lifetime. When Muslims fled Darfur on foot across Sudan to escape death, she was separated from her family and lost in the chaos of war. At six years old. Later, in a miracle of odds that expunged her bad fortune, she was reunited with her family in a camp.

I heard some months later that ROTC officials at her school had appealed her case all the way to the top, and she was allowed to dress as she wished on formal dress day.

During our first week in town, I mentioned to a local college professor that the place seemed “over-retailed.” Its shopping malls, chain stores, and specialty shops were part of the overall sense that it had a larger physical layout than its population would normally indicate. The historic downtown was in the middle of a comeback, with new restaurants and shops and breweries, as well as metal and stone statuary. But the edges of town, especially where interstate highways entered from east and west, north and south, were occupied by huge shopping malls, plus motels and chain restaurants. Sioux Falls is roughly the same size as Burlington, Vermont, which we would visit a few weeks later. But it has an incomparably larger number of McDonald’s and Subway franchises, plus Sonics, Olive Gardens, and Taco Bells, and every other standardized eating, shopping, lodging, payday-loan-giving establishment you would find anywhere. Walmart and Sam’s Club, Michaels and Lowes, big-box stores of any kind—they are all around, including in what has become the state’s largest tourist draw (yes, exceeding Mount Rushmore), the Empire Mall.

How, I wondered, did they possibly stay in business? Sioux Falls is not that big a town. “You’ll notice,” the professor said, “that we’re also ‘over-lawyered.’ And over-banked, and over-doctored and over-hospitalized, and over-serviced in any way you want to name.”

The reason, he explained, was the city’s emergence over the past generation as the economic capital of the region as a whole. If you lived within a couple-hundred-mile radius and needed to do back-to-school or special shopping, get a medical checkup, or spend money on entertainment, you were less likely to look in your own tiny Dakota town and more likely to go into Sioux Falls. The city’s economic-development leaders refer to this as its “fringe city” advantage, as the nearest biggish city for the surrounding rural areas in both Dakotas, Iowa, southern Minnesota, and northern Nebraska. The next level of bigger cities are “the Cities,” Minneapolis and St. Paul to the east, Denver to the west, and Omaha to the south, all more than casual-driving distance away.

This pattern is obviously bad for the much-smaller cities in the area—we heard about those who had lost their clinic or their school or their grocery store, as services concentrated in metropolises like Sioux Falls—but changed the character of Sioux Falls in a way we hadn’t expected, and that was a reminder of some classic chronicles of boom-era towns in the American West. What were some of the signs? Once we were alerted to watch for them, we saw more and more.

For all our days in Sioux Falls, we stayed in a bargain “extended-stay suites” motel right near the famed Empire Mall. The place was jammed on each of our visits: during the week, mainly with business visitors, but starting Thursday nights and through the weekend, mainly with families from farms and tiny towns who had come to shop and see the city. People also came for medical treatment at the area’s two big competing (both nonprofit) health-care systems, Sanford and Avera.

When we talked with college students at Augustana, the private Lutheran college, or the public universities, the most typical story was: I am from Spearfish (or Mitchell, Watertown, Brookings, Huron, Pierre, a farm twenty miles from the nearest town) and I’ve made it out of there for college. From them and other college-age people in the area we heard: Back in my town, the public school is shrinking or being consolidated (so we go to a regional school); the local grocery store is closing (because the owner got too old), so we take big shopping trips; the post office is closing; it’s only my parents (or my uncle, my grandparents, our old neighbors) who are back there, because it doesn’t take much manpower to run the farm.

We talked over pizza with a dozen students who had just graduated from a Sioux Falls public high school and were all headed off to college—most in the immediate area, one to the University of Nebraska, another to a small private school farther away. They were as bright-eyed and, yes, bushy-tailed as you’d expect from young kids from the Midwest, and we all gathered at the home of one of them. We asked how many of them had lived on a farm, and one or two hands went up. How many had immediate relatives still on farms or in small farming towns? All but one person.

“Our overall growth rate has been about one-third births, one-third people from smaller places in state, and one-third from out of state,” Reynold Nesiba, an economist from Augustana University (and later one of South Dakota’s few Democratic state senators), told me. (When I checked with him a few years later, he said that the international arrival rate had gone down, and the local birth rate had gone up.) “There are lots of people for whom this is the big city. And lots of people who grow up here may head off to Omaha or Minneapolis, but when they have their own families, they recognize that it’s a very nice place to live.”

One question on my mind as we set off to see the country and landed in South Dakota was “How will it sound?” Would the regionalisms of language be strong and obvious, or would the edges of American English have been flattened into submission by our shared national media, our easy communications, and the popularity of travel?

It didn’t take long before the first examples of regional language popped out, reassurance to me that they are alive and well.

On that Sunday in Sioux Falls, when Jim and I borrowed bikes from friends to ride the twenty-mile circuit circling town, we stopped to watch a fisherman casting into the stream that runs alongside a long section of the path. Just then, a serious fellow biker screeched to a stop and backtracked toward us.

I instinctively braced myself for the rebuke “GET A HELMET!,” which I hear when I sometimes ride helmet-free on the Capital Crescent Trail along the Potomac in Washington, D.C. To my surprise, the Sioux Falls rider started in with a friendly litany of “Are ya lost? Can I help? Ya need some direction?” I was caught off guard, then surprised at my own surprise by his friendly gesture here in the heart of the Midwest.

I also heard plenty of classic Dakota phrases. There were “You betchas,” sometimes in response to “Thank you.” And “Are you coming with?,” where the preposition hangs out there gratuitously, when “Are you coming?” would have been quite enough. A number of people suggested that the dangling “with” was a holdover from the German mitkommen, which would be comfortable for the 40 percent of South Dakotans of German heritage. Kommen Sie mit? Or literally “Come you with?”

I listened closely to people’s language during the interviews and conversations we had in Sioux Falls, with politicians and educators, city administrators, schoolkids, academics, newspaper editors, businesspeople and regular people. These happened in offices, at factories, or at pizza dinners with high school kids, during tours at public schools, home visits, casual encounters in restaurants, standing in lines, at museums, at local shops, at swimming pools, and, of course, over beers.

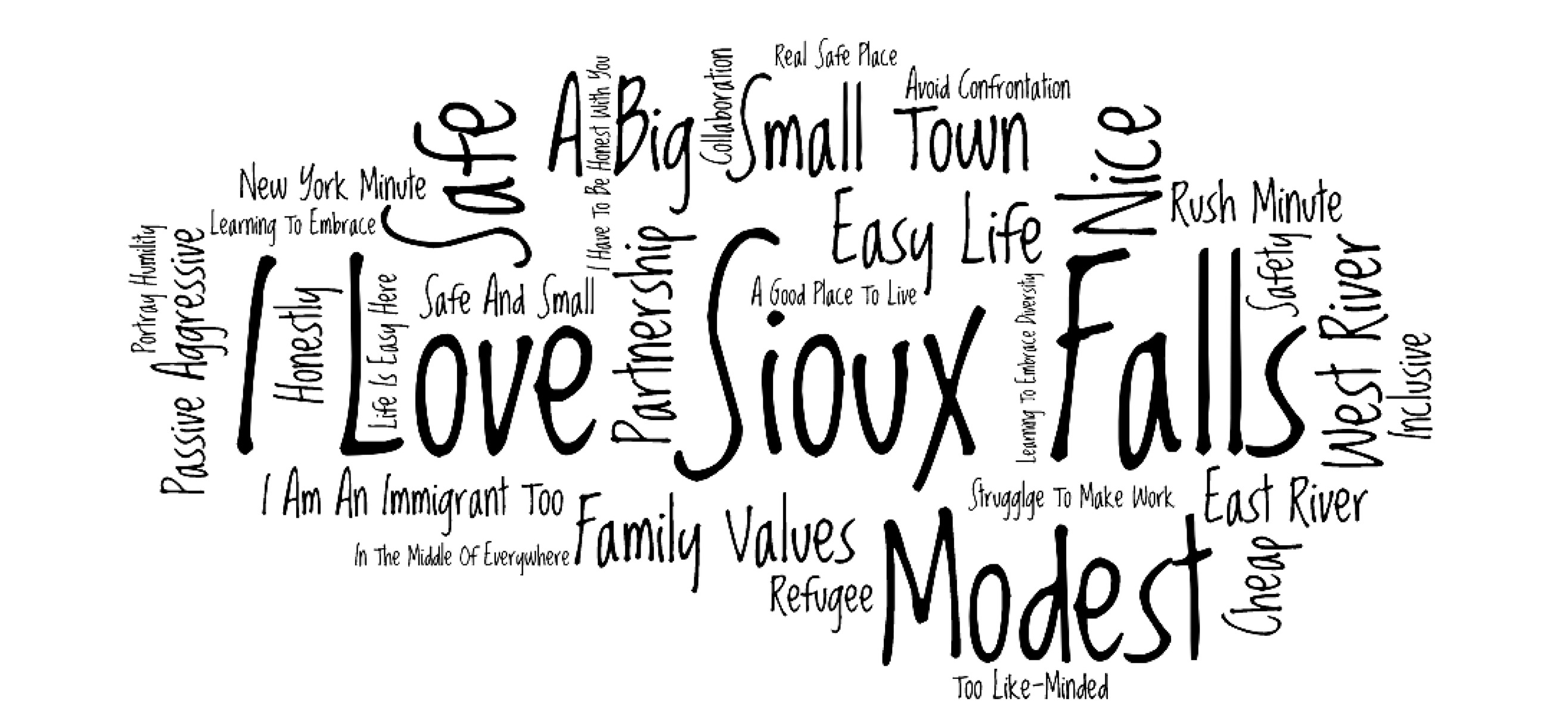

A number of Sioux Falls words and phrases popped out frequently, starting on our first night in town with the young women in the restaurant. All together, they formed a surprisingly coherent story of the culture of Sioux Falls. Opposite is the word cloud I put together, and what it taught me about Sioux Falls. The bigger the font, the more often I heard the word or phrase.

Who we are: So many words and phrases described how people felt about each other. Modest, nice, humble, nonconfrontational, inclusive. One person’s nice or humble in Sioux Falls is another person’s passive-aggressive and too much like-minded.

How we live: Here is the stuff of everyday life. Safe, safety, a real safe place came from the homegrown teenagers and their parents, who felt the kids could have the run of the town. It also came from recently arrived refugees who were either assigned to Sioux Falls or had found their way there as a second resettlement town, after hearing on the refugee grapevine that Sioux Falls was a safe place.

Easy life meant logistically easy, as in short commutes and drive times for errands or school. But here is how relative that description can be: one high school girl, a refugee who had walked across lawless South Sudan to her freedom, said that in Sioux Falls, she could walk merely a mile from her house to the grocery store, where she both worked and shopped. A mile, with groceries, in the South Dakota winter, I remember thinking at the time, and this was her definition of an easy life.

Our town: Sioux Falls is a big small town, said so many people. They clarified that they meant the town was small enough to protect and nurture, yet big enough that high school kids say they would like to stay or return one day, and the older generation extols its arts, higher education, recreation, and job possibilities.

If I heard this once, I heard it a thousand times: the references to East River and West River. I am sure everyone in South Dakota knows this, but for the rest of you, the demarcation refers to the Missouri River, which splits the state in half, not only geographically but also culturally, historically, politically, agriculturally, and economically. Locals could barely refer to it enough.

Two Sioux Falls words, honesty and collaboration, turned out to portend what I would hear later everywhere around the United States. At first, I thought they were special to Sioux Falls, but I soon learned that they are part of the new national vocabulary. Honesty, as in “I’ll have to be honest with you,” “honestly,” or “let’s be honest.” References to honesty caught my attention as I wondered why people in the Midwest would need to lean on such a qualifier. Weren’t they always honest? But once I noticed “honesty” in Sioux Falls, I started noticing it everywhere. Uttered by national pundits or chatty media, it arrives at my ears as a framing phrase that is less about honesty and more like “You may not like what I’m about to say, and I may not be comfortable with it either, so be prepared for what’s coming.” By the end of our journey, I’d heard these phrases used so frequently that they seemed whitewashed and barely registered anymore. As for the word collaboration, that’s another story. Remember it for later.

The grand finale: I love Sioux Falls! There is something about this phrase that is very disarming and genuine. I came to think that in its unabashed simplicity, it pretty well sums up how the residents of Sioux Falls talk about their town.