CHAPTER NINE  Eternal Lines

Eternal Lines

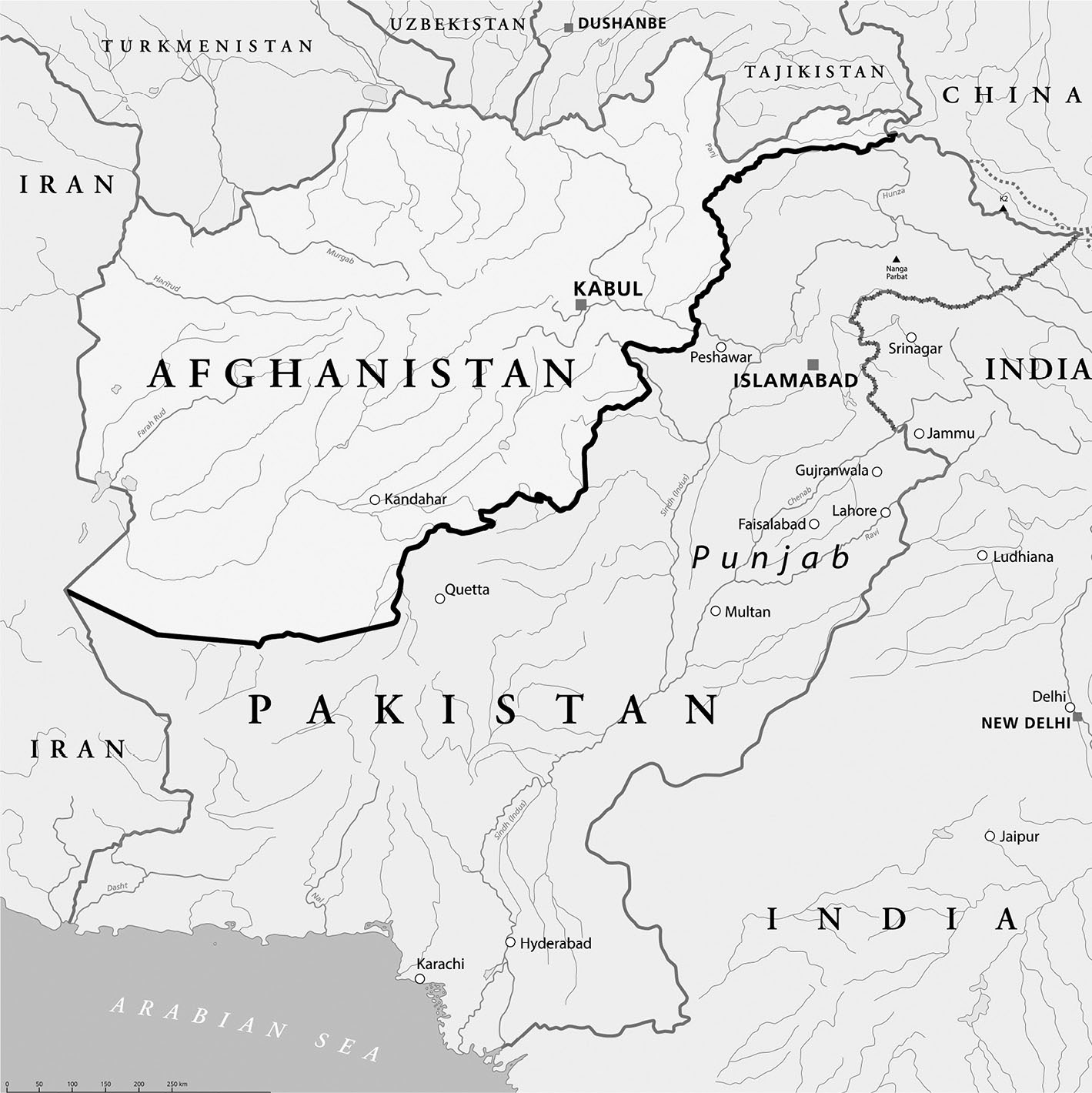

In 1884, the raj, the British rulers of India, which comprised the entire subcontinent including what is today India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and large stretches of Afghanistan, came to the conclusion that they no longer wanted responsibility for the wild territories of the Hindu Kush and what lay beyond to the west and south. These lands stretch from the impenetrable mountains they straddle on the north, where they merge with the Karakoram Range, the Pamirs, and the eternally tense point where China, Pakistan, and Afghanistan converge, and onward to the south, where they connect with the Spin Ghar Range near the Kabul River.

There have been tribes in these forbidding hills of Afghanistan for 2,000 years or more. The Greek historian Herodotus wrote in 440 B.C.E. of the Pactrians, one of the “wandering tribes” that occasionally helped comprise armies of Persia. These were the Pashtuns of the time of the raj, who still dominate much of the mountains, caves, and valleys of Afghanistan and the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan.

When the British assumed control over this vast region, there was resistance. Twice in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, British troops battled forces of the emir of Afghanistan. The first began in November 1878 when forces moved quickly into the emir’s territory, defeating his army and forcing the emir to flee. The British envoy, Sir Pierre Louis Napoleon Cavagnari, and his entire mission that had arrived in Kabul on July 24, 1879, were massacred to the last man on September 3, touching off the second Afghan campaign. This ended a year later when the British overran the entire army of Emir Ayub Khan outside Kandahar in southeastern Afghanistan, not far from the frontier that was about to be established. These wars, the diplomacy, maneuvers, and experience dealing with the Afghan people whom the British encountered, persuaded the raj that the price for retaining control was simply far higher than it was willing under any circumstances to pay.

So in 1884, Lord Frederick Hamilton-Temple-Blackwood, the Marquess of Dufferin, viceroy and governor of India, named Henry Mortimer Durand a member of the Afghan Boundary Commission. This was a critical post on at least two different levels. First, Russia was also beginning what would turn out to be a succession of attempts to push its own frontiers down into Afghanistan. Afghanistan was seen by the Russians, then the Soviets, then the Russians again, as a buffer against encroachment from the British Empire of that period, and against the potentially hostile and disruptive tensions on the subcontinent today. Ironically, Britain of the 1880s viewed Afghanistan through a similar prism—potentially a firm line that could not be crossed and that would keep the wild mountain tribes and the legions of Russians at bay. Durand headed off into the tribal lands of the North-West Frontier Province, beyond which lay Afghanistan. In 1885, a Russian delegation appeared as well at a neutral meeting place—the Zulfikar Pass. On July 16, 1885, The New York Times published a “special dispatch from Jagdorabatem via Meshed” telling of a “reported advance to Zulfikar Pass” that comprised “a large number of Russian reinforcement [that] has arrived at Merv and Pul-i-Khisti during the past fortnight.” At the same time, “the British Frontier Commission [was] moving nearer to Herat—the Afghans determined to resist invasion.”

If this sounds sadly, desperately familiar, it is because it was. History has never failed to repeat itself in this part of the world. Durand and his commission did finally succeed in arranging a truce and, most importantly, an agreement to establish a line to which his name was quickly attached and has persisted in some fashion or other until today. The Russians agreed to its provisions since it allowed their forces to control the sources of several critical canals. But it would be some years before any of this became reality. First, it was up to the emir of Afghanistan to agree. In April 1885, the British viceroy, Lord Dufferin, gave a lavish banquet in Rawalpindi where the emir praised the friendship between the two countries, as well as Durand. The viceroy promptly named Durand his foreign secretary, the youngest in the history of the British Empire. Over the next eight years, Durand traveled frequently to the hostile lands along the frontier, which he and his British colleagues saw as populated by “absolute barbarians… avaricious, thievish and predatory to the last degree.” In 1893, Durand planted himself permanently at the frontier, sitting day after day with the bearded emir, a series of rudimentary maps spread out before them to carve out the line that would define their mutual border. The one last sticking point was Waziristan—then, as now, a sprawling, provocative, and unsettled territory on the fringes of two empires. This was one stretch that Britain wanted very much to retain, largely as a buffer. Durand could hardly understand the emir’s apparently desperate desire to retain a place that “had so little population and wealth.” Why? Durand asked. A simple one-word explanation. “Honor,” the emir responded. This was easily satisfied by tripling the emir’s annual “subsidy” from the British Empire from six to eighteen lakh rupees ($8,000 to $24,000). On November 12, 1893, the agreement was signed, though the emir really had no idea what he was signing since the original was written in English, which he neither spoke nor read.

The Durand line establishes what is even today the boundary between Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Sir Olaf Caroe, who served as the last governor of the North-West Frontier Province in what was then India, and a firsthand expert on the Durand Line, which defined the western border of the territory he governed, observed that “the Agreement did not describe the line as the boundary of India, but as the frontier of the Amir’s [Abd-ur-Rahman] domain and the line beyond which neither side would exercise influence. This was because the British government did not intend to absorb the tribes into their administrative system, only to extend their own [British], and to exclude the Amir’s authority from the territory east and south of the line.… The Amir had renounced sovereignty beyond the line.” But a host of would-be interlopers, from Soviet invaders to Taliban freedom fighters to al-Qaeda terrorists, not to mention American forces and their NATO allies, never fully came to appreciate that reality.

Afghanistan still refuses to recognize this line, which effectively defines the border today, describing it as a colonial mandate imposed by force of will, though Pakistan freely accepts it as part of the legacy inherited, along with its freedom, at the time of the British exit from the subcontinent. It remains one of the longest-standing and firmest of such red lines, while also being utterly violent, unsettled, and, admittedly, quite porous.

But it is only one of three.

A second is in the Holy Land. For more than 5,000 years, from the time of the early Bronze Age, Jews and Arabs, or their antecedents, have lived side by side, dividing the Holy Land between them, initially with Jews against non-Jewish Canaanites, many of whom eventually embraced Christianity then, half a millennium later, Islam. By the late Bronze Age, Israeli tribes began to appear. By the late Iron Age, in the second millennium before the Common Era, there were already city-states in the Levant, what is today Israel and the Palestinian territories, many controlled by Egypt at the time. Maps of the Levant in the Iron Age already show quite well-defined areas of Israel, Judah, Moab, Edom, and Ammon (where Amman, Jordan is now located). Moreover, by the tenth century B.C.E., the time of Kings David and Solomon, walled cities, like Megiddo, were already flourishing, containing within their walls entire palaces.

The capital city of the region was already Jerusalem. By the year 850 B.C.E., there is also clear evidence of having been Israeli and Judean states, suggesting that even then, lines were being established not unlike those that exist, in a far more toxic fashion, today. The Jewish state of Israel was effectively destroyed by a sweep of Assyrian forces in 721 B.C.E. A century later, the Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar II completed the process, scattering Jews in what became known as the Babylonian exile, though many were able to return and build the Second Temple in Jerusalem in the mid-sixth century B.C.E. All this is to say that for nearly two thousand years, Jews and Arabs were living side by side in some fashion in what would become the Holy Land, each with their own very clearly defined lines of demarcation. Eventually, of course, Romans would conquer and overlay much of this region. Christianity would arrive, and, by the sixth century, Islam. But in each case, distinct communities with their own lines of authority that they were prepared to defend at all costs would emerge and managed to coexist until the modern era. Many were perhaps the oldest red lines of all.

The Levant during the Iron Age. A millennium before Christ.

Equally immutable, if less venerable, is the last of three unchanging, if not utterly unchallenged, red lines—the one that surrounds NATO, established by the Western alliance as a bulwark against all comers. First were the Soviets and their Warsaw Pact allies during the Cold War. Today, there is Russia and its outlying satrapies of Central Asia, the ’Stans, and a handful of outposts managed by the Kremlin from Moldava to Belarus. The origins of the NATO red line are those meetings of Roosevelt and Churchill in August 1941 on board the United States cruiser August and British battleship Prince of Wales anchored together off the coast of Newfoundland that we introduced in Chapter Eight. Initially, the document that emerged from what was a pre-war discussion (the United States still four months away from entering World War II) encompassed only Britain and the United States. But the eight points of what would become known as the Atlantic Charter included self-determination for all people without any “aggrandizement, territorial or other,” free trade, full economic collaboration, and abandonment of all use of force. This eighth and final provision was the most important for the future:

Since no future peace can be maintained if land, sea, or air armaments continue to be employed by nations which threaten, or may threaten, aggression outside of their frontiers, they believe, pending the establishment of a wider and permanent system of general security, that the disarmament of such nations is essential.

Both Churchill and Roosevelt returned to their respective capitals, each to a hero’s welcome. As New York Times correspondent James MacDonald reported: “Bronzed by the sun and sea breezes enjoyed during his historic trip for conferences with President Roosevelt, Prime Minister Winston Churchill arrived back in London amid vociferous cheers from an admiring populace.” It was, clearly the most singularly important moment for these two countries, which together would be responsible for building an impregnable line around themselves and their allies. Any doubt about the historic nature of this meeting was dispelled by the collection of dignitaries who met Churchill at King’s Cross Station when the train from the British coast arrived—Clement Attlee, Lord Privy Seal; Anthony Eden, foreign secretary; and Albert V. Alexander, first lord of the admiralty. Churchill’s speech to the British people describing the conference the following Sunday would be carried across the United States as well “by national networks.”

Eight years later, the document drafted by the two leaders, and particularly this final provision, would form the foundation for the NATO alliance. Its twelve founding nations pledged a common goal:

Its purpose was to secure peace in Europe, to promote cooperation among its members and to guard their freedom–all of this in the context of countering the threat posed at the time by the Soviet Union. The Alliance’s founding treaty was signed in Washington in 1949 by a dozen European and North American countries. It commits the Allies to democracy, individual liberty and the rule of law, as well as to peaceful resolution of disputes. Importantly, the treaty sets out the idea of collective defence, meaning that an attack against one Ally is considered as an attack against all Allies. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization–or NATO–ensures that the security of its European member countries is inseparably linked to that of its North American member countries.

The critical issue, and the heart of NATO’s virtual boundary lines, is the final one—detailed in Article Five of the alliance’s charter: one-for-all and all-for-one.

Over the next six years, the Soviet Union watched the growing unity of NATO with anxiety, along with the expansion of American forces in the nations that surrounded the Soviets’ European territories. Finally, in 1955, six years after NATO was created, and timed for the moment when West Germany joined the alliance, the Soviet Union created its own organization uniting its client states across Eastern Europe—Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Bulgaria, and Albania (until it withdrew in 1961 when it broke with Moscow and allied itself with China). Known as the Warsaw Pact, its boundary with the West was as inviolable as NATO’s boundaries with the East. There was one paramount difference. While the same concept of “an attack on one is an attack on all” was implicit in its nature, in fact this was not a mutual defense pact. No Warsaw Pact member was in any position militarily to confront a massive incursion from outside without the immediate involvement of the Soviet Union. While Britain and France each maintained its own independent nuclear arsenal, no Warsaw Pact nation other than the Soviet Union possessed any nuclear weapon. At the same time, as was demonstrated twice in its first fifteen years, forces of the Warsaw Pact, largely Soviet armored columns, were fully prepared to invade other members of the pact to enforce precise ideological adherence to the Kremlin line. In 1956 in Hungary and again in 1968 in Czechoslovakia, Soviet-backed Warsaw Pact forces rolled through these countries. In the first case, they violently suppressed the Hungarian Revolution, the second brought an end to the Prague Spring that threatened unchecked pluralism and criticism of Soviet domination of Eastern Europe. In short, all other elements of the Atlantic Charter—self-determination and freedom of choice in particular—had no place in the document that created the Warsaw Pact.

As a succession of other nations was added to the initial NATO dozen following the breakup of the Soviet Union, including all the founding members of the Warsaw Pact as well as the three Baltic Soviet republics (Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia), the red line that surrounded NATO expanded to fit. There has never been an overt effort to penetrate that line, as there was no effort to penetrate the boundaries of the Warsaw Pact when it existed. This effective red line has been as inviolable as any in the world. But as we shall see, not without being tested.

These three sets of red lines—the Durand Line, the lines that separate Jews and Arabs in the Holy Land today, and the boundaries of NATO—are what I would suggest are the intractable lines. These immutables are not, in the final analysis, red lines, but rather black ones. Each is a hard line that is likely never to be breached. We must find a way to live with them. For attempts to destroy them or erase them may be as pernicious and dangerous to the world order as allowing them simply to fulfill, yes, even at times exhaust, their intentions by allowing them to remain in place.

There has been no end of challenges to the Durand Line virtually from the day of its creation. Pakistan ultimately inherited the Durand Line and all the territories it guaranteed to the east and south when its nation was created from the partition of India in 1947 when Britain departed and the two nations gained their freedom. But the Pashtuns, who straddled this line, were given only two alternatives—join India, or join Pakistan. Neither the Pashtuns, nor the central government in Kabul, ever really recognized the 1,500-mile Durand Line as an international boundary. And in cultural, social, and especially tribal terms, it was not. It was, rather, an international no-man’s-land that has been all but immutable for its very failure to gain legitimacy by any of the real parties. Effectively, a red line recognized by neither side can be as indelible as one that is deeply contested by one party or another. Today, it is still tribal allegiances and realities that define this line and what lies on both sides of it. And the Pashtuns are the core of these problems.

On October 7, 2001, less than a month after the 9/11 terrorist attack on the United States, a plot masterminded in the mountainous region bisected by the Durand Line, American forces, joined by a smattering of NATO troops, invaded Afghanistan. Their principal goal was immediately successful—forcing the Taliban from power in Kabul, if not from much of the rest of the country and certainly not from the mountain ranges that straddle the Durand Line.

As it happens, Taliban means “student” in the Pashto language. The Pashtuns, collectively at least sixty tribes and upward of four hundred sub-tribes, are an immensely proud people—especially proud of their three-thousand-year history of never having been conquered by an invader (except perhaps briefly by Mongols sweeping through en route from Asia to the Middle East and Europe in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries). Pashtun folklore suggests the entire nationality sprang from a single ancestor, most commonly referred to as Baba Khaled—Khalid ibn al-Walid, the storied warrior of the prophet Mohammed. Today, Pashtuns number upward of forty million people who have managed to resist a succession of invading forces even in the last century that have sought to rule or control them. They managed to defeat the entire armored power of the Soviet Union, which in December 1979 launched a full-fledged Prague-Spring-style invasion of Afghanistan, which borders the southern reaches of the then-Soviet republics of Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan.

The real reason for the Soviet invasion did not come to light until years later. It was not the fear of the potential for terrorism that motivated the Kremlin to launch its ill-conceived and ill-fated action. Instead, it was really the same fear that motivated their actions in Hungary in 1956, Czechoslovakia in 1968, and later Georgia and Ukraine in the post-Soviet period. They worried that Afghanistan was on the verge of shifting its loyalties to the West. The last thing the Kremlin wanted was a member of NATO directly on its southern flank. It wanted a determinedly neutral power, or ideally one that was solidly pro-Soviet. If not a member of the Warsaw Pact, then certainly not a member of the NATO alliance.

What started out as a simple police action did not go well at all for the Soviets from the beginning. The Afghan resistance was all but immune to the Soviet military’s massive armor and air power, an army unaccustomed to fighting any sort of real guerrilla-style tactics. The Taliban, which came to full flower under the aegis of Pakistan’s ISI (Inter-Services Intelligence) and the American CIA, launched a fully declared jihad and began receiving major Western-style matériel, especially shoulder-launched ground-to-air missiles. The Soviet advantage of massive helicopter-borne assaults melted away. Scores of helicopters and their crews went down in flames. Body bags began returning to Russia in waves. And eventually it became impossible for even the awesome Soviet propaganda machinery to successfully deny the reality. The Soviets were losing. It took ten years for this truly to hit home. But finally, by February 1989 they were gone. The agreement had been signed nearly a year earlier by Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. The United States was a party to the agreement—pledging to end its support for the Taliban resistance. Of course, within two years Gorbachev was deposed and the Soviet Union dissolved. Without a doubt, the ill-fated Afghanistan adventure played an important, if not a singlehanded, role in this event.

The third signatory to the withdrawal document was Pakistan, which had played its own part in the Soviets’ defeat and agreed to end its interference in Afghanistan’s internal affairs. This worked, certainly for Pakistan, at least from the moment the Taliban assumed power in Kabul. That took seven tumultuous years—from the end of the Soviet departure in 1989 until 1996—and involved more unsettling tribal conflicts. A host of rival mujahideen groups vying for power and territory surged back and forth across Afghanistan—only confirming the fundamental reason for the original Durand Line. Finally, in 1996 the Taliban rolled into Kabul, seizing the capital and deposing the corrupt president, Burhanuddin Rabbani, who happened to be a Tajik, a tribe that served as a principal foe of the Pashtun people. Pakistan and the ISI were back in control. Their intention—which has held firm to the present day—has been to maintain the security of the Pakistani nation, whose western boundary continues to be defined by the Durand Line. Largely, this has led to the ISI’s determination to assist the Taliban at every turn. This meant also, from the get-go, an all-out effort to thwart the will of the American and allied forces that had invaded the country and unseated the Taliban in order to install a pro-Western government in Kabul. Pro-Western is inevitably anti-Taliban and, definitionally, anti-Pashtun.

I’ll dispense with the sad and sorry history of Western forces in Afghanistan—more than 2,000 American and 1,100 allied lives lost. The Costs of War Project of Brown University’s Watson Institute has documented at least 157,000 people who’ve died in Afghanistan since the American invasion in 2001. Nearly 2.4 million Afghans were effectively exiled as of February 2020, according to the United Nations High Commisioner for Refugees. The pace of this carnage has barely relented. In July 2019, the UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan recorded the highest number of civilian casualties ever recorded in a single month since its activities began ten years earlier. Long before this, the Afghan War had already become the United States’s longest conflict, eclipsing even Vietnam and World War II. And for what end? The various lines have held. The Pashtun are on the verge of reclaiming the entirety of their home territory, and then some.

So, what then? Throughout, there has never been much sympathy at all to dismantling the Durand Line and all it has represented. Beginning with the presidency of Barack Obama and accelerating under Donald Trump, there have been repeated efforts to reach some sort of condominium with the Taliban, if there is even any such unitary organization that can be addressed. Certainly, there is what is known as the Quetta Shura, reflecting the town of Quetta in Pakistan where the long-time Taliban leader Mullah Omar sought refuge after the Western invasion. The concept of a shura, Arabic for “consultation” dates back to Mohammed and the Quran, encouraging all Muslims to consult all those who would be impacted by decisions that might be taken on their behalf. The membership of the Quetta Shura includes leaders of a number of Taliban factions, particularly the deadly Haqqani Network that maintains close ties with Pakistan’s ISI and al-Qaeda, raising the specter of a return of the same rabidly anti-American terrorist organizations that launched 9/11, but are even more toxic today. Effectively, these Taliban have established an entire shadow government with every intention of reinstalling the same horrific power structure that terrorized women and girls who were deprived of any rights or education, destroyed historic monuments, and held the entire nation in the sway of a militant version of sharia justice underpinning one of the world’s most despicable dictatorships.

When the Trump administration decided it wanted out of this region whose lines it no longer had the remotest ability to control, it began a long series of negotiations with putative representatives of this very Taliban organization. From the start, however, there was never any real assurance that the Taliban with whom they were dealing represented the factions of the Quetta Shura most committed to total victory in any fashion. Nor was there any real assurance that all the shura’s members represented the entirety of the mujahideen battling American forces in the field or setting off deadly terrorist bombings in Kabul. At the same time, there were other separate diplomatic initiatives that threatened all such efforts to end the war and stem the Taliban’s march toward full control again of Afghanistan. Foremost among these moves was Trump’s own effort to cement a warm and deep friendship with India’s right-wing leader, Narendra Modi, climaxing in a whirlwind visit by Trump that all but utterly ignored Pakistan and its leader. Pakistan and India have had a fraught relationship since the moment of their partition following the British departure in 1947. Each has raised substantial nuclear arsenals, targeted primarily on each other. And while India has tried its best to cement a close relationship with the pro-American government in Kabul, Pakistan and especially the ISI have found it both necessary and opportune to cement their relationships with the Taliban and Pashtuns. What possible motive could there be for the Taliban to conclude any meaningful agreement with the United States that would build friendly forces on either sides of the historic Durand Line that would be antipathetic to their ultimate goals of a return to power?

In fact, there is one real motive for any diplomatic discussions: getting American forces out of Afghanistan. This would inevitably allow the Taliban to reassert its control over both sides of the Durand Line—precisely what would most likely happen after the conclusion of any agreement that appeared to be successful from the American perspective. Effectively, for the first time in its century and a half of existence, the Durand Line would cease, functionally, to exist. The results would be catastrophic for those who lived on both sides. With the Taliban and the ISI firmly in power, Afghanistan would revert to the medieval Islamic state it had become during the years prior to 9/11 and the American invasion. Yet President Trump was determined to go down as the individual who brought his troops home and ended the loss of American lives.

Trump was hardly the first to have attempted such an endeavor. As early as September 2007, Afghanistan’s president at the time, Hamid Karzai, offered to open discussions with the Taliban while George W. Bush, who launched the war, was still America’s president. Not surprisingly, the Taliban, still riding high and believing in their ultimate victory, rejected the overture out of hand. “Karzai government is a dummy government. It has no authority so why should we waste our time and effort,” Taliban spokesman Qari Mohammed Yousuf told Reuters. “Until American and NATO troops are out of Afghanistan, talks with Karzai government are not possible.”

Still, Karzai did not give up. In 2009, in a televised speech following his reelection, he told his people: “We call on our Taliban brothers to come home and embrace their land.” Mullah Omar was still very much in charge of the Taliban. He had no interest. The Taliban saw themselves then, and still do today, as a group with a very long time horizon and a font of human resources far broader and deeper in their lands than anything America or its allies might bring. Like the Vietcong and North Vietnamese before them, they could simply wait it out. Still, a June 2019 report from the UN Security Council observed that “one of the most significant developments of the past 12 months has been increasing pressure from ordinary Afghans to bring an end to the fighting.” This was a product of the latest of a string of unsuccessful ceasefires, from June 15 to 17, 2018, when some 25,000 to 30,000 Taliban “entered government-controlled cities, towns and villages. These Taliban engaged in direct peaceful contact… with government officials and members of the Afghan National Defence and Security Forces in an unprecedented display of good will.” The Taliban leadership panicked at this exercise and the potential outcome. By the second day, Taliban leaders called such behavior by their forces “treasonous” and ordered it to cease, a day later demanding that all its fighters “leave government-controlled areas by sunset of the same day and resume jihad against the Afghan government.” This reminded me enormously of the interaction between the Khmer Rouge and the Cambodian people in the final days of the war in Cambodia in 1975. Many Cambodians, including my interpreter and photographer, Dith Pran, wanted desperately for the war to be over at any price, even a Khmer Rouge “victory.” “Afterwards,” Pran would tell me before the final victory of the insurgents, “we will all find ways to live together in peace. After all, we are all Khmers.” How wrong that turned out to be. The Khmer Rouge, living apart from the vast mass of their people for so many years, engaged in desperate struggles against overwhelming forces of foreigners or locals backed by foreign armies, were determined to establish an utterly dissonant society. They were not “all Khmers” except in the language they spoke. There were the victors and the vanquished. The Taliban, I fear, have the same mentality. The Taliban leadership, according to the Security Council report, “took action to carry out a systematic replacement of all Taliban commanders believed to have shown reluctance in preventing their fighters from fraternizing with Afghan citizens in government-controlled areas. Those commanders relieved of their positions were replaced by more hardline Taliban, often from other provinces, or supported by the Haqqani Network.”

At the same time, the Taliban do not lack for resources. They maintain a vast annual income from a host of activities, which the UN singles out as “narcotics, illicit mineral and other resource extraction, taxation, extortion, the sale of commercial and government services and property, and donations from abroad.” They cultivate at least 263,000 hectares of poppy production (650,000 acres, more than 1,000 square miles, or nearly the size of the state of Rhode Island), exporting some $400 million worth of product.

Indeed, the Taliban has effectively been operating an entire nation in parallel with that of the government based in the capital of Kabul and established in elections that really encompass only the fraction of the geography and people of Afghanistan it controls. The new empire the Taliban will establish and the lines they will draw will be simply a reversion—even a more toxic version—of the one they had already established more than two decades ago. They have had all this time to understand more deeply the errors they made and that will not be repeated. There will be no tolerance, no sensitivity. Certainly, no democracy.

Still, America pressed ahead. Meetings in the last half of 2019 everywhere from Brussels to Moscow including Pakistan, France, Germany, Italy, Norway, Britain, the European Union, Russia, even China were intended to find some way forward. It finally all came together in Qatar. This Persian Gulf emirate has long sought to punch beyond its weight, and succeeded. It is in Doha that Al Jazeera, the Arab world’s leading television news network, was born and remains headquartered. Qatar has also served as the site and source of a host of important efforts at mediation from the moment in 1995 when Emir Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani assumed the throne of the tiny emirate. Early on, he served as a neutral party among a host of factions in Lebanon, where the emir cultivated close relationships with Hezbollah. He arranged for peace in Darfur, rallied the Arab League for interventions from Libya to Syria, even provided financing for Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood in the days following the Arab Spring. So, it was hardly surprising that the Taliban looked to Qatar when they were considering where to establish their first mission abroad. Qatar provided a most hospitable environment—comfortable homes, an entire lifestyle underwritten by the Qataris, even as the delegation’s numbers in Qatar grew from a handful to dozens.

The first talks began in 2010 and after two desultory years, sputtered as they focused on prisoner exchanges that seemed non-starters. The delegations included the insurgent group led by Mullah Omar and later his successors, traveling to Qatar via Pakistan. Still, there were other, especially toxic Taliban, most based in Afghanistan and scattered elements in Pakistan, who had never played a role in negotiations. In 2013, however, talks resumed in Qatar, and the following year, these Taliban negotiators won the release of five of their number who’d been imprisoned for thirteen years in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, in exchange for the freedom of Sergeant Bowe Bergdahl, who’d been seized after wandering off from his unit in Afghanistan five years earlier. The Taliban Five, as they became known, were flown to Qatar, where under terms of the agreement they were to be held for one year.

Five years later, they were still in Qatar. Talks continued on and off. But Donald Trump, who arrived in office in January 2017, was determined to go down in history as the person who ended America’s longest war. In September 2018, Trump named Zalmay Khalilzad, who’d served as ambassador to Afghanistan under George W. Bush, as special envoy to Afghanistan and the peace process. As it happens, Khalilzad, a Sunni Muslim, is himself an ethnic Pashtun, or at least claims Pashtun origins. Talks began shortly after his appointment. Across the table were Taliban leaders and, quite pointedly, the Taliban Five. On February 29, 2020, a peace deal was signed in Qatar in the convention hall of an opulent hotel by Khalilzad and Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, described as the deputy leader of the Taliban. What has never been perfectly clear is precisely what that meant. Which Taliban did he represent? As a witness to the signing was Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, who called the moment “historic.” The Taliban said they hoped it would lead to a “permanent solution” to the violence in Afghanistan. But even that seemed an open question. A precondition for the signing was a seven-day period of “reduction in violence” by all sides—American, Afghan, and Taliban forces who pledged no offensive operations. The calm appeared to hold. Just barely. Indeed, the Taliban’s spokesman in Qatar observed that with the signing, the period of reduced violence that was to last for a week had “ended.” The agreement also called for the Taliban to break with al-Qaeda. And intra-Afghan talks including representatives of the government in Kabul were to begin in ten days. Within 135 days, the United States also pledged a first withdrawal of 8,600 troops to be accompanied by a proportional draw down of other allied and coalition forces. From Washington, Trump issued a statement that contained considerable hope, perhaps more than might ultimately be warranted:

If the Taliban and the government of Afghanistan live up to these commitments, we will have a powerful path forward to end the war in Afghanistan and bring our troops home. These commitments represent an important step to a lasting peace in a new Afghanistan, free from Al Qaeda, ISIS, and any other terrorist group that would seek to bring us harm. Ultimately it will be up to the people of Afghanistan to work out their future. We, therefore, urge the Afghan people to seize this opportunity for peace and a new future for their country.

There was way more in this statement than was contained in the agreement. The hope was that this pact would return the region to much the same historic status promised by the Durand Line nearly a century and a half before. Still, there is the suggestion in its language of much of the lasting power behind any red line. “Ultimately it will be up to the people of Afghanistan to work out their future,” the President said. Indeed, any red line is in the final analysis no stronger than the will of the people on both sides to accept it.

The people on both sides of the Durand Line played little role in its establishment. But for generations they have learned how to live with it. Since at least 85 percent of the 1,640-mile-long line follows natural boundaries, from rivers to mountain crests, it bisects ancestral Pashtun tribal holdings and communities. More than forty million Pashtuns in the region would love to be united in a single nation, taking down the Durand Line and creating a nation of Pashtunistan, which would include some forty thousand square miles of territory inside Pakistan. That is unlikely ever to happen. But across a dozen or more mountain passes, the tribes have managed to maintain their identity and accept each reality that’s been presented.

Whether this can be accomplished peacefully now is another question entirely. Within three weeks of the signing of this agreement, it was already unravelling. In March 2020, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo flew to Kabul on an urgent “diplomatic rescue mission,” which failed to produce any path forward. To complicate matters, a deeply disputed Afghanistan election left the nation with two feuding presidents and their respective governments, each vying for control of whatever territory the Taliban does not control in whole or in part. On his way out of the country, Pompeo slashed $1 billion of some $4.5 billion in annual American military and political aid, threatening a repeat next year. His final stop, in Qatar, proved equally disappointing. The Taliban there pledged to avoid attacks on US forces, but in the three weeks after the agreement was signed, more than a hundred Afghan troops and civilians died in escalating violence.

“I went there to try and—I’m sorry,” Pompeo told the press traveling with him as he flew out of his final meeting in Doha. “Look, there’s places where progress has been made. The reduction of violence is real. It’s not perfect, but it’s in a place that’s pretty good. We’re continuing to honor our commitment that says that we will engage only when we are attacked. There haven’t been attacks on American forces since the peace agreement was signed, what, three weeks ago now, three and a half weeks ago.” And then he tossed off perhaps the most trenchant comment since the process began, and which bodes least well for the future: “There’s a long history,” said Pompeo, who at times seems to have a grasp of history, having graduated first in his class from West Point. “There are lots of power centers in Afghanistan.” And he concluded, “These are the expectations that we have, that the Afghans themselves will lead this path forward. Their leaders need to do that, all of their various leaders.”

What is especially telling is that at no time did Pompeo or any senior American official make contact with any official at a high level in Pakistan. In the case of any red line there must be buy-ins from both sides if it is to work and achieve long-term stability with any degree of peace. There is no sense that there is any real buy-in from Pakistan, especially its most independent-minded ISI. Nor is there any real indication of a buy-in from Taliban fighters out in the maquis, many of whom have been and will continue receiving help and support from Pakistani elements devoted to preserving Taliban loyalty to their anti-Indian agenda. Moreover, even if those negotiating do represent a body of the fighting force, there is no sense that Western negotiators will ever be in a position to sit down across a table from the most obdurate, those most committed to an armed solution to the entire problem. These remain utterly committed to waiting as long as it takes to arrive at one. Such complications will inevitably transcend any agreement that may be signed in Kabul, Doha, or any other location.

And the question of peace on two sides of an intractable red line is the same dilemma that has confronted Palestinians and Jews two thousand miles to the west.

As we have seen, Jews have been an integral part of the Holy Land for at least two millennia, living side by side with a host of conquerors and indigenous non-Jews—first with Arab Christians after the first century C.E. and, eventually, after the arrival of Mohammed five centuries later, with Islamized Arabs. They were subsumed into the Ottoman Empire, where they managed to coexist for four hundred years with the Islamic rulers of Constantinople as key elements of the province of Syria. By 1896, they had become a majority in the city of Jerusalem. Four years earlier, Chaim Weizmann, born in Belarus, part of the Russian Empire, left for Germany to pursue his studies as a chemist, working as a Hebrew teacher at a Jewish boarding school to earn a meager living. He’d already embraced Zionism and by the time he moved to England as a brilliant young chemist, he was fully committed to turning Palestine into the Jewish homeland. Shortly after his arrival as a professor at the University of Manchester, Weizmann met Arthur Balfour, the local MP and later foreign secretary during World War I. At the same time, however, Weizmann was pursuing his experimental work in chemistry. And shortly before the outbreak of hostilities, discovered a way of artificially creating acetone, a critical component in making the cordite explosives integral to bombs. At about that time, Britain was also seeking a way to weaken the Ottoman Empire and build its own influence in the Middle East. Weizmann had developed this pitch:

Should Palestine fall within the British sphere of influence and should Britain encourage a Jewish settlement there, as a British dependency, we could have in twenty to thirty years a million Jews out there, perhaps more; they would develop the country, bring back civilization to it, form a very effective guard for the Suez Canal.

His pitch contained three central and powerful elements for British politicians of the time that would lead to the creation, three decades later, of the State of Israel: Palestine for the British, development and modernization of a desert wasteland, and a loyal and powerful ally prepared to do battle in defense of the Suez Canal—the fastest and most direct route to India and the East. Britain’s indebtedness to this brilliant young chemist and its own self-interest in building its presence in the Middle East and protecting the Suez Canal, while at the same time weakening the Ottoman enemy, were a decisive and politically potent cocktail. David Lloyd George would later tell friends that he had “rewarded” Weizmann with a Jewish homeland in Palestine for his donation of the formula to produce vast quantities of acetone. In fact, the political and diplomatic pirouette that led to this homeland was a trifle more complex. The route wound through a friendship that had developed between Weizmann and Sir Mark Sykes, chief secretary of the war cabinet who, with his French counterpart, François Georges-Picot, drafted the secret Sykes-Picot Agreement dividing the Middle East between the two allied powers. This pact rewarded a large swath of Palestine to the French, though the war cabinet, even Sykes himself, believed Britain had every right to much of Palestine, Greater Syria, and Iraq, which the agreement had awarded to France. Weizmann lobbied mightily for the position that France should have rights that did not extend beyond “Syria, as far as Beyrouth [since] the so-called French influence which is merely spiritual and religious, is predominant in Syria. In Palestine, there is very little of it.… The only work which may be termed civilizing pioneer work has been carried out by the Jews.”

On November 18, 1917, with Weizmann waiting outside the door, the War Cabinet met, with Lord Balfour presenting a text. Minutes later, Sykes emerged, waving the document, proclaiming, “Dr. Weizmann, it’s a boy.” In fact, it was the Balfour Declaration, framed as a letter from Balfour to the powerful leader of the British Jewish community Lord Lionel de Rothschild:

His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a National Home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of the existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews of any other country.

Chaim Weizmann meets Faisal bin Hussein (Aqaba, Jordan).

Weizmann promptly set off on a trip to Palestine for a meeting in the desert, arranged by T. E. Lawrence, with the Arab leader Faisal bin Hussein, third son of the grand sharif of Mecca. Lawrence believed the Jews could do much to advance the Arab agenda in the region—namely ridding themselves of their Ottoman overlords. The result was a two-hour conference in which the Zionist leader explained that the Jews intended “to do everything in our power to allay Arab fears and susceptibilities, and our hope that he would lend his powerful moral support.” Over thick, sweet coffee and tea there was very much a meeting of minds, so much so that Faisal insisted that a remarkable photo be taken of them outside his tent, Weizmann donning the traditional Arab headdress atop his three-piece white linen suit, Faisal in the robes of a Bedouin warrior.

Of course, there was much work left before the Jewish state of Israel would be created three decades later. In 1922, a British census showed the total population of Palestine as 757,182 people, “of whom 590,890 were Mohammedans, 83,794 Jews and 82,498 Christians and others.” Then the Jewish migration began. By 1930, there were 162,059 Jews and 692,195 Muslims, though the birthrate was higher among the Muslim population. When the Jews came, they were prepared to pay for Arab lands where they might settle, though in 1922 they held barely 14 percent of the total arable land. The same British census document observed:

The Arabs have regarded with suspicion measures taken by the Government with the best intentions. The transfer of land ordinance [of] 1920, which requires that the consent of the Government must be obtained to all dispositions of immovable property, and forbids transfer to other than residents in Palestine, they regard as having been introduced to keep down the price of land and to throw land which is in the market into the hands of the Jews at a low price.

The basis was being laid for future problems between the Jews and the Arabs, who would see themselves as increasingly disenfranchised and impoverished. In the course of the 1930s, the trickle of Jews to Palestine rose dramatically—from 3,265 in 1930 to a peak of 61,458 in 1937. At the same time, the mix was beginning to swing as well—Jews with 17 percent and Arabs 74 percent of the population in 1931 to 30 percent and 60 percent respectively by the end of the decade. By the time of the creation of the State of Israel in 1948, Jews outnumbered Arabs 716,700 to 156,000.

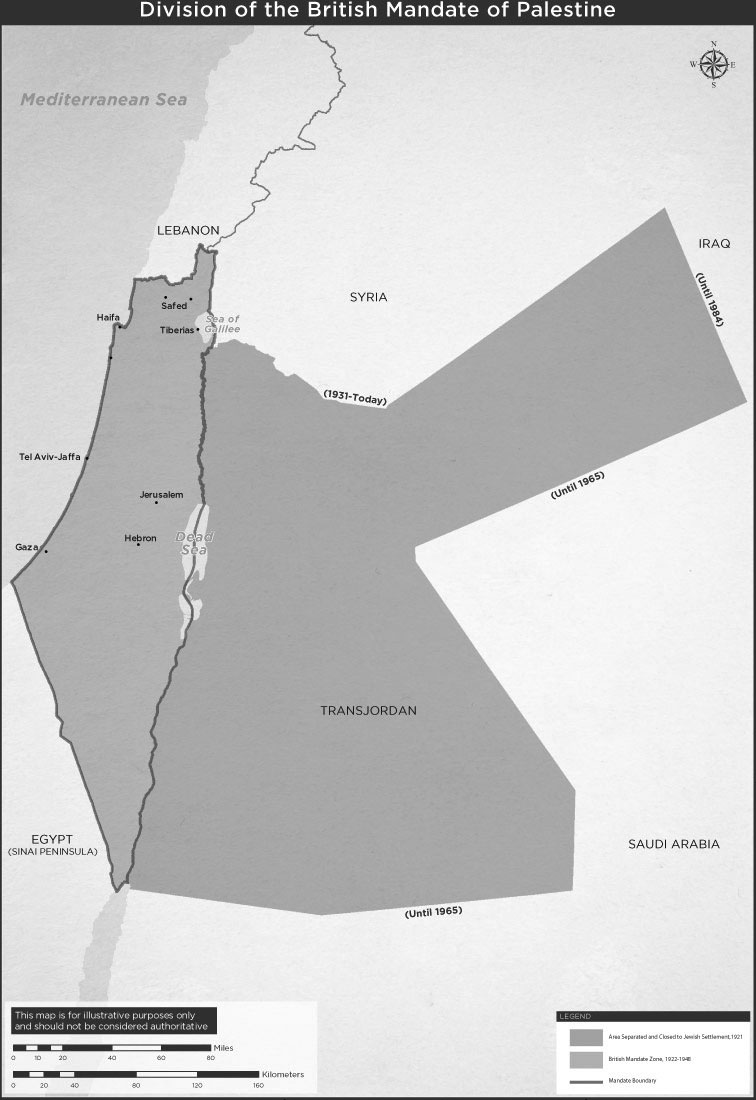

The physical boundaries of the State of Israel were effectively drawn and little changed by the British in the course of their mandate over Palestine. This included what is today considered the Palestinian territory of Gaza (a theoretically self-governing territory of Israel) and the lands along the West Bank of the Jordan River. From the moment of its creation, Israel was challenged by massive armed reactions from Arab armies. At least three times over the next half century—the Arab-Israeli War of 1948, the Six-Day War of June 1967, and the Yom Kippur War of October 1973—Arab forces attempted to force their way past the red line that was Israel’s fiercely defended boundary.

The British mandate over Palestine: the Jewish settlements west of the Jordan River and the eastern region, closed to Jewish settlements beginning in 1921.

Each time, Israel fended off these attacks from the outside, even managing to expand its frontiers, in the face often of all but unanimous condemnation by the outside world, including the United Nations and its Security Council. After the 1948 war, with the Green Line border—a red line that held for nineteen years until the Six-Day War—Israel retained territories that included East Jerusalem, the West Bank, Gaza Strip, Golan Heights, and Sinai Peninsula. Little of this territory was part of the original boundary established by Britain when it allowed the creation of the Jewish state. But Israeli leaders believed that retaining and expanding the nation’s red lines provided vital buffers against further challenges, including the expansion of Israel’s “narrow waist” that could be used to divide Israel in half. Palestinians and their organizations, particularly the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), had by that time seized on the Gaza Strip and the West Bank as their future homeland, though Israel still considered them as having been absorbed into its newly expanded home. Following the Six-Day War, Israel seized the Golan Heights, but as part of the truce agreed to return the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt and the Golan to Syria. It retained the Gaza Strip and the West Bank—which put Israel in direct conflict with the view of the UN Security Council, which voted unanimously on November 22, 1967, to approve Resolution 242 introduced by the British representative, Lord Caradon. It called for Israel to relinquish these territories and even drew a map of what it viewed as the nation’s new red line.

Firm lines begin to be drawn, all too often at the tip of a spear.

Six years later came the Yom Kippur War, a joint surprise attack by a coalition of Arab armies on the holiest day of the year in Judaism. Egyptian forces crossed the Suez Canal and advanced through the Sinai, while Syria struck from the Golan Heights. The Israeli military retaliated by air and land on all fronts, and within two weeks of the invasion had utterly humiliated the entire Arab armed force. Finally, US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger called a news conference at the State Department, proclaiming:

Our position is that… the conditions that produced this war were clearly intolerable to the Arab nations and that in the process of negotiations it will be necessary to make substantial concessions. The problem will be to relate the Arab concern for the sovereignty over the territories to the Israeli concern for secure boundaries. We believe that the process of negotiations between the parties is an essential component of this.… We will make a major effort to bring about a solution that is considered just by all parties.

Kissinger recognized that the Palestinians needed some hope of a future homeland, perhaps outside of the Israeli envelope. “Palestinian interests and aspirations are a reality, and the U.S. has recognized publicly that no settlement is possible without taking them into account,” Kissinger wrote in a “top secret/eyes only” cable to General Vernon Walters, who was in touch with Palestinian leaders. “In the context of a settlement, the U.S. would be more than eager to contribute to the well-being and progress of the Palestinian people.”

Since the Yom Kippur War, the last full-scale conflict between Israel and any external armed force, there have been a host of efforts by internal and outside parties and military groups to breach or shrink the red line that Israel has long maintained and sought to expand. Two intifadas, or large-scale Palestinian uprisings against Israel in Gaza and the West Bank, were accompanied by a war in southern Lebanon that Israel launched in an effort to break down the paramilitary forces of Hezbollah. In between, there were innumerable actions by Israel against Palestinian forces and the militant organization Hamas, now the de facto governing authority of the Gaza Strip—often efforts to halt rocket and other attacks on Israeli border settlements.

A number of diplomatic initiatives were launched with the same end in view. Six months after the Yom Kippur War, Henry Kissinger, Secretary of State and National Security Adviser to President Richard Nixon, embarked on two extended sets of “shuttle diplomacy”—traveling, with a team of aides and a phalanx of journalists, between Cairo and Jerusalem in January and again in May of 1974. He was accompanied by his principal deputy, Peter W. Rodman, who helped Kissinger chronicle this extensively in Years of Upheaval and for the Office of the Historian of the State Department.

His first trip brought an end to the uneasy truce between Israel and Egypt and staged a withdrawal by Israel from the Sinai Peninsula, shrinking the red line that had expanded exponentially at the end of hostilities. In eight vigorous days, Kissinger bludgeoned both sides into a first pullback, and in September 1975, a second disengagement that would have the effect of removing Israel largely from the Sinai Peninsula. Its red line retreated up the Gulf of Aqaba to the southern tip of Jordan, where it remains today. It would also leave Egypt in control of the vital Suez Canal and the Gulf of Suez, though it would guarantee the right of Israeli shipping to transit the Canal, the Straits of Tiran, and the Bab el-Mandeb.

In May 1974, Kissinger tried his same magic on Syria with another round of shuttle diplomacy between Jerusalem and Damascus, with the added hope that an agreement on that front would persuade OPEC to lift the embargo on oil shipments to the United States that was crippling the American economy. On May 31, the two countries signed an agreement and Israel pulled out of the Golan. The Israeli red lines had effectively returned to the status quo ante bellum, where they remain today.

A succession of future peace negotiations, some more or less successful, had little or no impact on the configuration of the red lines that divided Israelis from their Arab neighbors. Jimmy Carter, his National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski, and Secretary of State Cyrus Vance engineered the Camp David Accords after bringing Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin together with Egyptian President Anwar Sadat for twelve days in 1978. It was, in many ways, the most consequential of a host of such peace negotiations, though in the end the United Nations refused to recognize it. The Camp David agreement did result in, as Jimmy Carter would later put it, “Arab recognition of Israel’s right to exist in peace,” effectively recognizing the red lines surrounding the Jewish state that had existed at least since its creation in 1948. Israel also pledged “withdrawal from the occupied territories, with exceptions to be negotiated for Israel’s security.” The pact also established, as Carter put it, “a contiguous, or Palestinian state, with—to use Prime Minister Begin’s phrase, ‘full autonomy for the Palestinians’ or to use his more precise phrase, ‘Palestinian Arabs’—because he maintained to me that Israeli Jews were also Palestinians.” The final provision was “an undivided Jerusalem” which was in the end deleted from the final document. And, as Carter conceded twenty-five years later, “those were the basic elements for peace, but obviously, peace was not achieved.”

What is critical for this discussion, however, is not the issue of a lasting or especially comprehensive peace but rather the nature of the territory and the boundaries that were left behind. The land of Palestine—Gaza and the West Bank—remained from the Israeli point of view within the borders of Israel, as it recognized the envelope of its frontiers. Under the Camp David Accords, the Palestinians were given the right to establish a “self-governing authority,” which has done little to change any of the boundaries involved. The United Nations General Assembly quickly and definitively refused to recognize the Accords since neither the UN nor the PLO (then under the leadership of Yasser Arafat) participated in the negotiations and the Palestinians did not win the “right of return,” self-determination, or national independence and sovereignty, as was available to Jews and Israelis. Effectively that would have meant dramatically redrawing Israel’s red lines, very much endangering the viability of these lines and the security of the Israeli heartland.

Twenty years later, in September 1995, President Bill Clinton tried again, bringing Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and PLO chairman Yasser Arafat together in Washington to conclude a new agreement. This time the negotiations would include the Palestinians. The resulting document detailed the establishment of Palestinian entities on the West Bank and Gaza, particularly the Palestinian Council and an “elected Ra’ees of the Executive Authority” to govern both areas. Sadly, it did little to ease the ongoing levels of tension, all too often erupting into violence in both areas that continues now and likely well into the future along the lines of demarcation that were established, only with some largely unworkable elasticity.

At the same time, this only elevated what is effectively an existential debate that has continued as a basso continuo to Israeli politics for much of Israel’s existence—a one-state versus a two-state solution to the Palestinian question. Should Palestinians and their Gaza and West Bank territories be simply incorporated into the State of Israel and all Palestinians become full-fledged Israeli citizens? Or should Gaza and the West Bank become a separate, recognized Palestinian nation? There is a fundamental problem.

The land area of Israel and the two Palestinian territories is wildly unbalanced—respectively 21,671 square kilometers versus 5,506 square kilometers. But the Palestinian population has been increasing at a dramatically faster rate than the Jewish population. In March 2018, Colonel Uri Mendes of the military-run civil administration of the West Bank and Gaza told the Knesset (the Israeli parliament) that West Bank territories’ population alone totaled “between 2.5 million and 2.7 million,” though he conceded that a Palestinian census showed that number as closer to 3 million. Add in 2 million that Avi Dichter, former head of the Shin Bet internal security force, estimates live in Gaza and you have nearly 5 million Palestinians. Combined with 1.84 million Arabs living inside Israel, you arrive at nearly 7 million Arabs, as well as a small number of Christians, all within what would be the boundaries of a single, unified Israeli state. According to the Israeli Census Bureau, that is nearly the same as the number of Jews living in the State of Israel. Moreover, Palestinian families are averaging five children (down from seven, twenty years ago), outpacing Jewish population growth. This means that within the next decade, Jews would become a minority in their own land. The situation could well become not unlike that of South Africa under apartheid, when a white minority was governing an oppressed and disenfranchised majority—becoming a global pariah among nations as it sought to defend its own utterly indefensible (on moral, political, and diplomatic grounds) red lines. Or, alternatively, a Jewish minority would be governed—if the same democratic model of government were maintained—by a Palestinian majority. Israel’s red line frontiers, then, would become all but meaningless. None of this seems very likely to happen. A two-state solution would seem to be the only viable formula for maintaining the seven-decade-old red line of the Israeli frontier.

Effectively, however, for nearly two decades, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has been endeavoring, through a creeping red line, to resolve this problem without another full-scale war, but at the same time without enfranchising the Palestinians. Netanyahu has led Israel for some fourteen years over two separate stints that straddled two centuries. Three months into his second term, in June 2009, the prime minister announced the road map for his version of a two-state solution: immediate renewal of talks with the Palestinian Authority for self-government, as long as that doesn’t endanger Israel; West Bank settlements would not be “an obstacle to peace.” But even then, it became clear that the train was poised to go imminently off the rails. A freeze on new construction of settlements on the West Bank was nothing more than a pledge—at least for a certain limited time—and with no enforcement mechanism. Barack Obama, whose special envoy George Mitchell was in charge of talks with the Israeli government, was never happy at all with the pace or direction of negotiations on such a freeze, which turned out to be utterly ephemeral.

Over the next dozen years, settlements continued to mushroom, stretching the eastern red line of Israel recognized by UN fiat and international law far into areas nominally Palestinian but, in reality, firmly behind the Israelis’ intended red line. In March 2020, Israel’s defense minister, Naftali Bennett, even approved a master project, called “Sovereignty Road,” designed to separate Palestinian and Israeli motorists, as one Israeli journalist put it, “to enable construction of settlements of a highly sensitive area… near East Jerusalem.” Such a project had been frozen for nearly a decade. Now it was full speed ahead.

All this was happening just as Donald Trump was unveiling his own, stillborn peace plan for Israel. Early in his presidency, Trump put his Jewish son-in-law, Jared Kushner, in charge of this delicate, highly fraught subject. The then thirty-six-year-old New York real estate developer had no diplomatic experience and for much of the early gestation of this project was even denied top secret security status that seemed indispensable for his success. Moreover, if there were ever an opportunity for either side to come together on such an agreement, that possibility ended a month after Kushner’s appointment with the decision announced on December 6, 2017, by Trump to move the American embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. The status of this city, it must be remembered, has never been fully adjudicated between Jews, Muslims, and Christians, since all the major religions have important claims on parts of the Holy City. Palestinians were outraged. Five months later, on May 13, 2018, when the ceremony of transfer was held, more than 10,000 Palestinians protested along the border fence with Gaza, leaving 2,700 injured, with at least 1,350 wounded by Israeli military gunfire and 58 killed, including several teenagers. Jared Kushner attended the opening ceremony, standing in front of a huge American flag and embassy seal as a video message from his father-in-law played to the gathering. The president pledged the United States “remains fully committed to facilitating a lasting peace agreement.”

There followed two years of frantic settlement building across the West Bank. “Netanyahu has chosen to cross the red lines and take us all with them,” Nir Hasson, a columnist for the leading Israeli daily Haaretz, wrote in February 2020. Construction on the West Bank, he continued, “makes a future Palestinian state unimaginable.” Still, desultory discussions continued between Kushner and Israeli officials, since the Palestinians declined even to receive Kushner or any other American as long as the embassy remained in Jerusalem.

Then, on January 28, 2020, President Trump, joined by Netanyahu at the White House, unveiled the peace plan. The outlines of the full 181-page plan were simple. The most critical issue, for this discussion, is the precise boundaries of the “new” Israel and the territories identified as Palestinian. As many commentators in both the United States and Israel observed, “The maps show Israel, the West Bank and Gaza Strip as a single unit, a series of numbered ‘Israeli enclave communities’ in what is today the West Bank.” The fifteen carefully named and numbered “Israeli enclave communities” are settlements that Netanyahu managed to have established before the map was printed. Some sort of tunnel is also shown running beneath Israel and connecting the two enclaves—Gaza and the West Bank.

Jared Kushner’s “Vision for Peace”… conceptually.

The Palestinian authority promptly labeled the entire deal “utterly unacceptable and grossly unjust.” Indeed, the “talking points,” which Kushner and the State Department cabled to all American embassies, a copy of which was obtained by Politico, were all but ludicrous in many of their claims:

- This is the first time Israel has ever agreed to a public map detailing the borders of a two-state solution.

- For the first time, the State of Israel has agreed to recognize a future State of Palestine, based on a map that is included in the Vision.

- This Vision ensures the future State of Palestine is viable, connected, and reasonably comparable in size to the territory of the West Bank and Gaza pre-1967.

- Israel has agreed to comport its policies to this Vision for at least four years, including freezing all settlement activity in the West Bank in areas that this Vision designates for the future State of Palestine.

- The status quo is not acceptable.

On August 13, 2020, Trump triumphantly announced, in a tweet, a first major breakthrough toward redrawing at least a portion of the century’s worth of red lines that had threatened to harden irrevocably in this region:

HUGE breakthrough today! Historic Peace Agreement between our two GREAT friends, Israel and the United Arab Emirates!

The United Arab Emirates agreed to establish formal diplomatic relations with Israel. Trump credited his son-in-law, though it is likely that other forces were at work—especially a fear of Iran’s growing reach and hostility that screamed out for a more united and coherent response across the region. But of greater importance to the geography of red lines was the quid pro quo to which Israel agreed. As the White House put it:

As a result of this diplomatic breakthrough and at the request of President Trump with the support of the United Arab Emirates, Israel will suspend declaring sovereignty over areas outlined in the President’s Vision for Peace and focus its efforts now on expanding ties with other countries in the Arab and Muslim world.

There were certain red flags immediately visible in this statement. First, Israel had only agreed to “suspend” declaring sovereignty over the new territories. It had done so before and quickly regressed. Second, there appeared to be a certain conditionality that ties with other Arab nations might be necessary before there was any permanent Israeli agreement to establish firm new lines with these territories in Palestinian hands.

Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, crown prince of Abu Dhabi and deputy supreme commander the UAE armed forces has long served as a major power broker in the region. If the pact with the UAE could be cemented—the first with a major Arab nation since Israel and Jordan signed a peace agreement in October 1994—then it is not inconceivable that similar agreements could be concluded with Saudi Arabia or other regional powers that could force Israel really to adhere to the boundaries agreed upon in the UAE accord.

Of course, there have been any number of maps delimiting red lines, the boundaries of Israel, the extent of its penetration into conquered territories, and its willingness to withdraw over the past seventy years. In the Kushner peace map delineating the new boundaries of Israel and Palestine, there is a host of other problems. The tunnel that appears to link Gaza with the West Bank territories is itself stunningly ill-conceived. Would Israel ever let a tunnel be built entirely under its land that could be a focal point of attacks on Israeli territory above? It has done its best to dismantle a number of tunnels built into Gaza, for instance, that have been used to smuggle arms and explosives into this Palestinian territory from Egypt. Freezing settlement activity on the West Bank, of course, has never happened at all, as the map accompanying the “Vision” so graphically demonstrates.

About all that is accurate in these talking points is the final one. The status quo is indeed not acceptable, not even tenable in the final analysis. Does that mean, however, that this—one of our three intractable red lines—is in danger of dissolution? Not at all. Creeping red lines—for this is precisely the nature of the lines delimiting Israel’s liquid frontiers—may hold for a very long time if there is a surfeit of power on one side. But in the long run, they will never work. What is essential is for a brilliant, well-intentioned outside arbiter with no clear agenda to find a way of making these lines permanent, or drawing them in a fashion where everyone on both sides can live and prosper.

Two decades ago, I had lunch in New York with an Israeli minister of finance. He had an interesting idea. Why not, he posited, help the Palestinians really understand the value of a cooperative arrangement that could reach across this red line, the failings of which he understood with profound clarity. He’d begun already, in fact, to establish a fund that would finance, using Israeli and American private and public funds, new and vibrant Palestinian businesses. By seeing graphic demonstrations of what was possible—jobs, growth, prosperity, and peace—might his adversaries not appreciate the real, human, and material value of a bridge? It seemed like a brilliant and utterly worthwhile idea. Two months later, he was ousted in one of the innumerable cabinet shuffles that have made Israeli politics and its revolving-door democracy so problematic in the pursuit of peace and a stable red line regime. His idea died with him.

Vladimir Putin has never been very happy about the extension of the immutable line that defines the peripheries of NATO, especially as the alliance expanded dramatically with the addition of former Warsaw Pact allies, even former Soviet republics, as his beloved Soviet Union came unglued. He has repeatedly poked and prodded it, testing it at every perceived vulnerable point. Putin came to power at a particularly tumultuous moment in Russia’s history. Russia was on the verge of collapse. In the midst of a vicious war in the breakaway province of Chechnya, a series of bombings of massive apartment blocks in Moscow, Buynaksk, and Volgodonsk, left more than three hundred dead and a thousand injured, spreading fear across the country. The economy, too, was collapsing. A decaying, alcoholic president, Boris Yeltsin, named former KGB officer Vladimir Putin as his prime minister. Putin went to work. On December 31, 1999, Yeltsin resigned and Putin took over. For the next five years, Putin focused on bolstering the impoverished nation, building on the support of a host of oligarchs, and quickly strengthening Russia’s armed forces.

By 2007, Putin was ready. His first direct target was the former Soviet republic, now independent nation, of Estonia. As detailed in Chapter Five, Moscow embarked on a full-scale, eventually crippling, cyberattack that lasted three weeks and was quickly traced to Russian sources. Estonia had become a member of NATO just three years earlier along with the two other Baltic republics, Latvia and Lithuania. Several years later, when I visited Estonia, I asked its foreign minister at the time, Urmas Paet, why his nation had not invoked Article Five of the NATO charter, which holds that an attack on one member is an attack on all. There were no actual casualties of this war, Paet told me. That was his red line. Unlike the 9/11 attack—the only time in history that Article Five has been invoked—this one had not led to any loss of life. What it did accomplish, however, was the creation in May 2008 of the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre. Located in an old Soviet-era brick military post on the outskirts of Tallinn, it has been transformed into a bulwark against large-scale attacks on NATO by any power, with Russia clearly the leading target. Indeed, the Kremlin seems to have learned that lesson. NATO’s cyber red line has never been tested again in any such systematic fashion. Even the Russian attack on the United States’ 2016 election processes never rose to the level of virtual invasion as the across-the-board attack on Estonia’s entire infrastructure and government. Putin has clearly learned, at least in this respect, how far he could go.

One of Putin’s objectives is to reassemble, wherever possible, the Soviet empire, which in his heart he believed had been torn apart unreasonably. Following in Yeltsin’s footsteps at least in this one respect, Putin has had some success in retaining a number of former Soviet republics, particularly the Asian ’Stans. Putin’s efforts have succeeded in several respects. Effectively, he has been building his own new red line in opposition to NATO and with a nod to the old Warsaw Pact. Forming the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), each member state, with the exception of Moldova, signed the Collective Security Treaty, known as the Tashkent Pact, though Uzbekistan has since withdrawn. Like the Warsaw Pact before it, the military forces of the various members have held periodic maneuvers to “boost [their] joint defense capabilities,” according to Russian news dispatches. Moreover, the FSB, the successor security service to the Soviet-era KGB, maintains close ties with the security services of most of these states, particularly in the Central Asian regions, according to two Russian investigative journalists, Andrei Soldatov and Irina Borogan, who have made a career out of chronicling the work of the FSB at home and abroad. In 2000, the year Putin came to power in Moscow, “Russia backed the establishment of a CIS Antiterrorist Center, headquartered in Moscow with a Central Asia branch in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan,” Soldatov and Borogan wrote, adding that its “mandate was to create a database for intelligence sharing among the security services of all member countries.”

All of these nations are Putin’s “near abroad,” and he has been determined to make certain that he holds his friends close and any potential enemies closer. Clearly, the Baltic republics were a difficult loss. But having been gathered behind the NATO red line, reclaiming them was just one step too challenging. Not surprisingly, Putin’s next two adventures were against Georgia in 2008 and Crimea, followed by Ukraine itself, in 2014. These two adventures have proven to be substantial victories for Putin. His seizure of Crimea and prompt incorporation of this strategic region into the Russian nation was the first substantial redrawing of Russian boundaries since the collapse of the Soviet Union itself. But the rest of these adventures also had some profound successes in that they had the effect of redrawing psychological red lines that are equally strategic to Putin and, conversely should be equally disappointing to NATO. Neither Georgia nor Ukraine—despite their election of pro-Western leaders in recent years—have taken any significant steps toward joining NATO. In December 2017, at a NATO foreign ministers meeting, the alliance’s secretary general observed broadly, “The Alliance is fully committed to providing Georgia with the advice and tools it needs to advance toward eventual NATO membership.” The operative word, no doubt hardly lost on the Kremlin, was “eventual.” Two years later, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov pointed out on the occasion of resumption of direct flights between Russia and Tbilisi, “I confirm that we do not want to see NATO near us,” adding that if Georgia did accept an offer of NATO membership “we will not start a war, but such conduct will undermine our relations with NATO and with countries who are eager to enter the alliance.”

This has hardly exhausted Russia’s efforts to test NATO’s red lines, or its patience. Russia has repeatedly sought to flex its muscles in and around NATO’s borders, particularly on the oceans and in air spaces around the northern NATO periphery. Among the most blatant such actions took place in August 2019 in the Norwegian Sea. Some thirty ships of the Russian navy including the Severomorsk, a 535-foot guided-missile destroyer, and the 4,500-ton frigate Admiral Gorshkov, armed with cruise missiles, together with submarines and supply vessels as well as anti-submarine and strategic aircraft, undertook what Norway’s Chief of Defense Haakon Bruun-Hanssen called “a very complex operation” designed to demonstrate Russia’s ability to block NATO’s access to the Baltic Sea, North Sea, and Norwegian Sea—NATO’s entire northern flank that includes the three Baltic states as well as Scandinavia and Germany. “This is an exercise where Russia seeks to protect its territory and its interests by deploying highly capable ships, submarines and aircraft with the purpose of preventing NATO of operating in there,” said Bruun-Hanssen. “Any allied attempt to strengthen Norway becomes very difficult.” And this was only the latest such operation, the commander observed.

Six months later, British monitoring picked up seven Russian warships that were “lingering” in the English Channel, forcing the Royal Navy to deploy nine of its own ships to monitor them as they lingered off the coast. “The navy has completed a concentrated operation to shadow the Russian warships after unusually high levels of activity in the English Channel and North Sea,” a navy statement said. “Type 23 frigates HMS Kent, HMS Sutherland, HMS Argyll and HMS Richmond joined offshore patrol vessels HMS Tyne and HMS Mersey along with RFA Tideforce, RFA Tidespring and HMS Echo for the large-scale operation with support from NATO allies.” Russian warships often travel through the channel to and from the Baltic and the Mediterranean. This time, they just hung around. Too long. The naval activity followed two incidents when RAF Typhoon jets scrambled to intercept Russian TU-142 Bearcat bombers north of the Shetland Islands and heading into transatlantic passenger airline routes.