1

Who Is the Raw Cat?

THERE IS ANOTHER cat living inside your cat. Strip away the “creature comforts”—the cat beds, the mouse-shaped toys, a life spent looking out the window, or lying peacefully on the couch. You might see a glimpse of that other cat when she wakes you up in the middle of the night hunting your toes under the blanket—and there you’ll find that “other” whom I call the Raw Cat. In essence, the Raw Cat is your cat’s ancestral twin. These twins, separated by eons, are nonetheless in very close contact, as if there were a tin-can-and-string telephone connecting them through their DNA strands. Through that straight and unadulterated line, the Raw Cat sends constant transmissions to your companion about the urgency of securing territory, hunting, killing, eating, and staying ever alert, because just as cats hunt, they are also being hunted.

Everything about our cats, from their territorial identification and nutritional requirements to the ways they play and behave, are linked back to their raw twin. These characteristics all represent a shared prime objective, passed down with minor dilution, over tens of thousands of years. In fact, when you take into consideration how many traits—both physical and behavioral—that your cat has retained from the Raw Cat, it’s safe to say that from an evolutionary standpoint, these twins are almost identical.

Throughout this book, I’ll be asking you to tune into your cat’s rawness because that’s where Mojo lives. You’ll start to recognize when she’s tapping into her Raw Cat, and you’ll learn the importance of knowing how and where that happens. But I also want you to have a true 360-degree perspective of her moment-to-moment actions, and that only reveals itself once we understand why the pulse of the Raw Cat beats so close to the surface.

RAW CAT ROOTS

Once upon a time—a really long time ago—the first inkling of cat-ness happened when carnivores appeared on earth. Carnivores evolved from smaller mammals around 42 million years ago. Members of this order (which includes cats, dogs, bears, raccoons, and many other species) are defined by the structure of their teeth—which are designed to shear meat—and not by their diet. (Some members of the order Carnivora are omnivorous or even vegetarians.)

The Carnivora (evolutionarily speaking) split into two groups, or “suborders”: the doglike animals—called the Caniformia, and the catlike animals—called the Feliformia. And what exactly helped define them as “catlike”? Well, what would you call a group of ambush hunters who tended to be more carnivorous than other members of Carnivora? I’d call that the very Rawest Cat!

![]()

Cat Daddy Fact

The genomes of tigers and domestic cats are over 96 percent similar—meaning the proteins that make the cat “blueprint” are organized similarly in many cat species.

A BEAUTIFUL MUTATION IS BORN! HOW NEW SPECIES COME ABOUT

As we’re looking at our evolutionary cat timeline, you might be asking, “What’s with all of these splits and divergences?” They mark periods when there was an ancestral species—the grandparent of all those cats, so to speak—and from that grandparent, a separate family branched off to do its own cat thing.

Specifically, new species form when genetic changes occur over time and cause populations to mutate. These changes often happen when a group of animals becomes isolated from other members of the same species. This can be due to changes in the environment—perhaps an area becomes more or less protected, or prey abundance shifts—leading some animals to move to a different territory. There can be proximity barriers, such as when islands form or a new river emerges, creating separation between groups. And there can be behavioral factors—for example, when nocturnal animals are less likely to mate with animals who are active during the day.

Cat Nerd Corner

Far East, Far Out: The Origins of the Siamese Cat

When cats spread to the Far East around 2,000 years ago, there were no local wildcats for these newcomers to interbreed with. This genetic isolation led to some mutations related to appearance, which led to several of the distinct features of the Oriental breeds—including the Siamese, Tonkinese, and Birmans. Recent DNA studies suggest about 700 years of independent breeding from other breeds, and while still the same species as other domestic cats, have a genetic profile that suggests they have a unique ancestor with origins in Southeast Asia.

These genetic changes are usually physical (if the two species have different features) or reproductive (when two species cannot interbreed) in nature. But the lines can get a little blurry—as demonstrated by the ability of humans to produce several kinds of hybrid cats. Nonetheless, the faster the animals can reproduce, the quicker these changes can take effect (in evolutionary time, of course) and lead to new species.

THE SMALL CATS

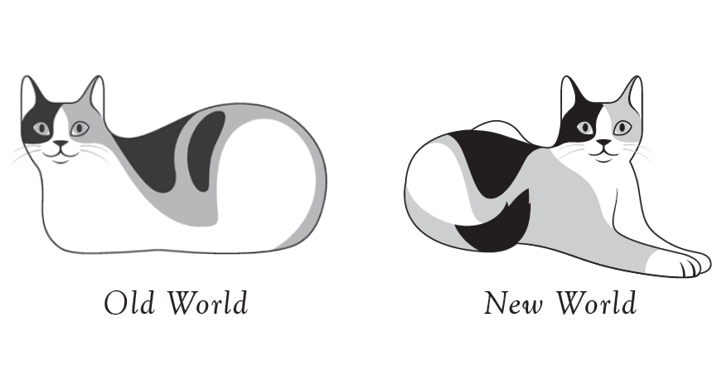

Small cats can be further classified as either Old World (from Africa, Asia, or Europe) or New World (from Central and South America). Old World cats include domestic cats, wild cats, fishing cats, lynx, bobcat, caracal, serval, and cheetah. New World cats include ocelots, Geoffroy’s cat, and pumas.

There is not as clear a division between the New and Old World cats as there is within other species of animals, mainly because all cats are evolutionarily pretty tightly knit. However, there are a few behavioral differences. For example:

- Old World cats lie with their paws tucked under the body (in the “meatloaf position”), while New World cats do not.

- Old World cats are less likely to pluck the feathers from their small bird prey, while New World cats are inclined to thoroughly pluck before eating their birds.

- Old World cats bury their poop, while New World cats do not. (Imagine how different our litterbox situation might have played out had our beloved house cats descended from the New World, rather than the Old!)

![]()

Cat Daddy Fact

All big cats roar (except for snow leopards), but they don’t typically purr (except for cheetahs). Small cats purr, but can’t roar. This is due, in part, to a small bone in the neck called the hyoid. In big cats, this bone is flexible, but in small cats, it is rigid. The big cats also have flat, square vocal cords, and a longer vocal tract that allows them to make a louder, lower sound with less effort. In small cats, the hardened hyoid combined with vocal folds are believed to create the purring sound.

Roaring may give big cats another way to control their turf without fighting or engaging in face-to-face conflict. Its sheer volume is a long-distance message—“I’m here, keep your distance please.” (For more on purring, see chapter 4.)

With all of this talk about what separates Old and New World, big and small cats, and small from one another, we might forget the most remarkable, undeniably raw fact: all existing cat species (currently estimated at forty-one) share a common ancestor. That means that all felines are obligate carnivores, with large eyes and ears, powerful jaws, and a body built to kill. All cats walk quietly on their toes, with protractible claws, which supports their silent stalk-and-rush hunting style. And, last but not least, perhaps the most unifying (and definitely the most Mojo-rific) force connecting all felines, from lions to tabbies, is the drive to claim and own territory.

THE ROAD TO LESS WILD: THE “DOMESTICATION” STORY

It is difficult for scientists to form a really clear timeline of the recent domestication of cats, because genetically, physically, and behaviorally they are so similar to their closest wild relatives (so much so that there’s been a lot of interbreeding among domestic cats and other wildcat species). In fact, the word “domestic,” when applied to cats, has always struck me as fundamentally . . . well, just wrong. I don’t believe cats have ever been fully domesticated. This speaks to my insistence at seeing the rawness in your cat at all times. To me, in each moment that you identify the Raw Cat in your cat, you are disproving the very notion of domestication. That said, as we continue with our story here, let’s take a look at what we do know about how the Raw Cat gradually transformed into what we now call the “house cat.”

For thousands of years, cats lived with and around people, but were never completely dependent on them. F. s. lybica—the ancestral species—appears to be one of the more tameable of all the closely related wildcats, suggesting a predisposition for living with humans. Ultimately, though, the pathway to evolution was laid by the benefits that cats and humans mutually provided for each other. As agriculture began to flourish in our earliest human settlements, the rodent population drastically increased. This made proximity to humans attractive to cats, and the natural pest control they provided attractive to humans. This would prove to be a recurring “win/win” theme throughout history.

GODS AND MUMMIES

The downside of any long-term relationship between humans and animals is that it’s not an equitable one. Humans, through the centuries, unfortunately always held the cards and could be very harsh in how they dealt those cards out. In general, cats seemed to be revered in proportion to how much a cat’s pest control prowess was needed. That said, the true human/cat roller coaster ride began in earnest as humans were left to simply appreciate cats for their unique personalities and brand of companionship. As the ride heated up, gaining momentum and speed through history, our feline friends often found themselves reviled . . . to the extreme.

We’ve all heard stories of cat worship in Egypt. But it’s important to note that the Egyptian economy was highly dependent on grains . . . which means agriculture . . . which means rodents . . . which means, once again, cats playing their welcomed role as “nature’s exterminator.” This likely set the stage for the elevated status that would come to them in Egyptian society. (Contrast this, for example, with the many parts of Europe where weasels were already playing this exterminator role, so cats were not of particular use.)

Still, the Egyptians revered cats, perhaps like no other culture. Cats were depicted throughout Egyptian artwork, lived in religious temples, and were kept as pets. The intentional harming of a cat brought serious penalties, and if a cat passed of natural causes, the human family would shave their eyebrows to mourn. This feline worship/devotion is documented through the mummification of cats, who were often prepared for a life in the afterworld with mummified mice to accompany them.

But even in the cat-loving environs of Egypt, the aforementioned roller coaster would take a few unfortunate plunges. Not all mummified cats were cherished pets. They were also used as offerings to deities, and the demand for these offerings led to cat “breeding mills,” so cats could be deliberately killed and mummified.

The prophet Muhammad was another cat lover, and in Islamic cultures, cats have always been appreciated for more than just their extermination skills. According to one of the most well-known stories about Muhammad’s reverence for his beloved cats, when he was called to prayer and his favorite cat, Muezza, was sleeping on the sleeve of his prayer robe, Muhammad cut off the sleeve of the robe rather than disturb Muezza. (Sound familiar? How many of you have forgone getting off the couch because you had a cat asleep on your lap?)

In other parts of the world where cats were worshipped—particularly in pagan cultures—cats’ hallowed status became tainted as the persecution of non-Christians increased. In fact, things got really bad for our cat friends during the Middle Ages, when they were associated with cults and declared unholy. It is believed that millions of cats were sentenced to death and burned in witch trials or thrown into bonfires. And if cat owners tried to protect their pets, they would face inquisition themselves.

The sad irony is that during this time, the Black Death spread and killed thousands of people. Rats (or rather the fleas they carried) were known carriers of the plague, and killing massive numbers of cats would have certainly contributed to the proliferation of rats. Granted, archaeologists have more recently called the relationship between rats and the spread of the plague into question, suggesting that the plague spread so quickly due to close contact between humans, not between rats and humans. Regardless, killing thousands of cats could not have helped matters.

Even today, superstition and stigma continues to color folks’ perceptions of cats. We’ve all heard “Don’t let a black cat cross your path,” or that cats can “steal a baby’s breath.” And even though cats are more popular than ever, we still kill them in mass numbers in shelters every year, and there has even been a widespread call to eradicate feral cats from the outdoors. Hopefully, these ideologies will soon become part of our past as well.