4

Communication

Cat Code Cracking

THE CONSISTENT FEEDBACK (or rather, the absolute teeth-clenching, neck-vein-popping, eye-rolling frustration) that I’ve encountered over the years from adopters, clients, My Cat from Hell viewers, and, hell, just strangers on the street—is that cats are inscrutable. There is a pretty volatile combination at play when it comes to the cat/guardian relationship. When we don’t understand what cats are trying to communicate through their behaviors, we try to figure it out and are met with a blank stare. That look becomes a blank canvas for all kinds of projections from humans. Let’s say you are sitting in the living room, watching TV. Your cat comes into the room and, without hesitation, walks up to your gym bag—and pees in it. I mean, talk about a potentially explosive moment! What immediately makes a bad situation worse is you, executing a slow boil and assuming that you know what he is trying to tell you (“I hate my dinner,” “I hate the fact that you left me for twelve boring hours today, and you do it every single day,” “I hate your new girlfriend,” or, if you are circling this particular drain, that last big blast of projection, “I hate you.”).

Depending on how crappy your day has been up to that point, and perhaps how many times your cat has executed such blood pressure–spiking actions in the past, the speed at which your relationship deteriorates can be dizzying—and dangerous. I’ve seen a bond that was already a bit shaky crumble in that moment like a house of cards. And once that house comes down, well, your cat already has a paw out the door. It has been a fundamental part of my job since the beginning to interrupt this downward spiral before it gets to that irreversible point. Don’t forget, I began counseling guardians while working at an animal shelter, on the phone as they were asking me how much we charged to take back their cat. I know all too well where that downward spiral leads: to a homeless cat in a cage.

Through Dog-Colored Glasses

Part of the issue is that we, perhaps subconsciously, look at cats through dog-colored glasses; that is to say, we expect them to communicate with us in a way that we can instantly recognize. As you can guess by now, that expectation goes against the entire history of our relationship to cats. We’ve molded dogs over thousands of years to be recognizable, to reflect humanness back at us. We’ve bred in attributes that benefit us because, to boil it down, one of our main desires is companionship. That was never the priority in our relationship to and with cats. Remember that it was all about what was mutually beneficial when cats acted as hunters who protected our food supply. So to suddenly expect your cat to change his fundamental communication style after all this time is foolhardy at best.

Between the two worlds of humans and cats, the two languages, there is a fence. We must meet at that fence. Dogs will gladly jump the fence and run to our side in order to communicate; cats simply won’t, because that has never, until this point in our relationship, been part of our arrangement.

That said, the language of cats is just as eloquent as that of any other species on Earth. You just have to commit to meeting at the communicative fence. From cat-specific vocalizations to body language to behaviors like, yes, peeing—it all adds up to form a linguistic whole that, once learned, will make for a much more fulfilling relationship—and one not fraught with resentment.

So let’s dig in and start with how cats “talk.”

MORE THAN MEOWS: THE TALKATIVE CAT

Chirrups. Trills. Purrs. Yowls. Snarls. And of course, meows. Your cat can make up to a hundred different sounds, which is more than most carnivores (including dogs). Of course, if you have a “Chatty Catty,” that might seem like a lowball estimate. Why do cats have so much to say? Vocalizations can be ferocious or friendly; they might say “stay away” or “come closer.” Calls can provide information from a greater distance than just body language can, and may even tell the listener how big and strong the sender is.

Let’s consider three facts: feral cats are typically quieter than their domestic counterparts; many vocalizations are directed toward humans; and there is a wide range of individuality when it comes to how talkative a cat is. Genetics may play a part, as some breeds—namely, Siamese, Oriental, and Abyssinian—tend to be more vocal than your average cat. But we can assume that we humans have played a large role in how verbose our cats are. After all, meows get attention, which often leads to food, petting, or getting a door opened. It’s interesting to note that cats rarely meow at each other, with the key exception being the cry of kittens in distress for their mom.

Cats use other sounds to communicate with each other. Some of these sounds, like the meow, start with an open mouth that closes during the sound, such as howls and sexual calls. The less friendly calls are made with the mouth held open—those yowls, growls, snarls, hisses, and shrieks that are heard during fighting or are a response to pain.

Perhaps the cutest and friendliest sounds that cats make don’t require them to open their mouths at all. Purrs, chirrups, and trills are reserved for greetings and personal contact.

WHAT’S UP WITH THE PURR?

Purring is one of those Mojo Mysteries that we still don’t totally understand. It is usually a positive response, but sometimes cats purr when they are stressed, in pain, or even dying. Either way, we’re pretty sure that the purr is not under the cat’s conscious control, but is more like a reflex. The brain sends a signal to the muscles in the larynx, or what we call the voice box. These muscles move the vocal cords at a rate of approximately twenty-five times per second while cats inhale and exhale, which produces that distinctive rumble we call a purr.

Purrs help the Raw Mom Cat keep kittens nearby—the kittens’ purrs tell Mom they are nearby, and the purr helps with bonding by releasing self-soothing endorphins and lulling the kittens to sleep.

Purrs might have healing powers; they are in a similar range (20 to 140 Hz) to sound frequencies that help with both healing injuries and improving bone density (at least for cats, anyway; to date, the evidence on healing human bones is inconclusive). This may help explain why cats who are wounded or sick will often be purring.

I’ve heard speculation that a cat’s purrs during the killing bite can aid in lulling the prey into a catatonic state. But they might manipulate us as well. A 2009 study by Dr. Karen McComb and colleagues demonstrated that humans could tell the difference between a purr that a cat was making while soliciting food—which they labeled an “urgent” purr—from a nonurgent purr. The urgent purrs included a high-frequency component that indicated some level of excitement that we pick up on, and probably respond to with attention or food.

![]()

Cat Daddy Fact

The Guinness World Record for loudest purr is held by Smokey, a British cat who could purr at 67.7 dB (about as loud as conversation in a typical restaurant).

THE TOOTH CHATTER

It’s a common sight: Your cat is staring at a bird through the window, locked in with complete focus. Then this crazy chattering, quacking sound comes out of your cat’s mouth. What the heck?

Many cats chatter their teeth when they see prey that they can’t get to. Some will even chatter at other cats. One idea is that your cat is expressing frustration that they can’t get to that delicious bird. Some think the tooth movement is your cat practicing their “killer bite.”

The theory with perhaps the most weight is that cats are mimicking the sounds of their prey. Margays, Amazonian wildcats, mimic the sounds of tamarin monkeys to lure them within pouncing distance. A 2013 Swedish study showed overlap between the types of sounds birds make and the sounds emitted by cats during the chatter, including chirps, tweets, and tweedles. Makes sense, doesn’t it? The Raw Cat, more than most predators, will find a novel way to secure its kill. Wolf in sheep’s clothing? Try the Raw Cat in bird’s clothing. Anyhow, for now, we’ll have to chalk this one up to Mojo Mysteries, but it might be another example of how vocalizations have evolved to help cats get what they need.

BODY LANGUAGE

Cats tell us a lot through their bodies. While all cats will have subtle differences in how they communicate what they are feeling—whether confident, relaxed, fearful, defensive, or ready to attack—there are some general signals they use, with both humans and other cats. Many of these signals are inherited from their Raw Cat ancestor, which, as you will see, sometimes creates challenges for the modern cat.

The Tail

A cat’s tail serves many purposes. It helps with jumping and balance, and can even provide warmth and protection. But when a cat is sitting, or walking slowly, the tail is free to communicate. The cat’s tail can send several different messages because the tip can move independently from the rest of the tail.

In the Raw Cat’s ancestral environment (grasslands), the tail was likely a good long-distance signal of a cat’s emotional state. Strutting by with the tail in the air is a Mojo moment. The “tail up” with a curve at the tip is a classic friendly or playful greeting that says “hello,” or “right this way, follow me.”

As the tail lowers, the message might change a little. An ambivalent tail is slightly lowered, at more of a 45-degree angle.

The tail at “half-mast,” or horizontal to the ground, can be neutral, friendly, or even tentatively exploratory, and requires more contextual information for interpretation.

A “tail down” can serve a few different functions. Cats slightly lower the tail while stalking prey. But a cat might also be trying to make himself smaller by lowering the tail, assuming either a defensive or fearful posture. In extreme cases, the lower tail is accompanied by the “army crawl,” or walking away from a potential threat quickly and as low to the ground as they can get.

The tail between the legs is the most extreme expression of fear.

A bristled tail generally signifies DEFCON 1. It can be offensive or defensive, but it is often a response to something alarming in the environment.

A quivering tail (sometimes referred to as “mock spraying” since that’s exactly what it looks like) is usually a sign of positive excitement. In my experience, I’ve noticed the “mock spray” directed either at or near a person the cat is fond of. I can only guess that this signifies ownership with a posture that walks the tightrope between confident (body scent marking, rubbing, etc.) and unconfident (urine marking) cat language. Either way, I’ve learned to take it as a pretty high compliment!

Tail lashing is often an indicator of impending aggression or defensiveness, while smaller, subtle twitching movements can indicate frustration or irritation. (See “The Energetic Balloon” in chapter 7 for more on this.)

Cat Nerd Corner

The Tail-Up Studies

In a 2009 study of a feral colony in Italy, cats were observed for eight months. Researchers noted combative behavior between cats, which included biting, staring, chasing, and fighting. They also noted avoidance behaviors such as crouching, retreating, and hissing; and friendly behaviors, which included sniffing, rubbing, and presenting the tail up.

The “tail up” was most often directed toward aggressive cats by nonaggressive cats, suggesting it might be a message that says “I come in peace” and could also inhibit aggression in another cat.

To further demonstrate that the tail up served the function of expressing “Hey, I’m friendly,” John Bradshaw and Charlotte Cameron-Beaumont studied how cats responded to just silhouettes of other cats with different tail positions. This would rule out the possibility that the cats in the study were responding to other things aside from the tail up (like pheromones, vocalizations, or other aspects of an in-person interaction). The result? Cats would approach the image faster and raise their own tails in response to a “tail up” silhouette. When they saw the “tail down” silhouette, cats tended to respond with tail twitching, or by putting their own tails down.

The Ears

The ears can move subtly, quickly, and independently, which is why they are often the most telling aspect of a cat’s body language. They can be the first indicator of a cat’s emotional state. More than twenty muscles control the movement of the ears, and they are always ready to spring into action, even when your cat is resting.

Upright ears allow cats to take in and respond to auditory information in the environment. For a relaxed cat, the ears will be upright, but slightly rotated to the side. When the ears are more forward facing, your cat is on alert, or maybe even frustrated.

Flattened ears can mean different things. If the ears are sideways and down, your cat is fearful, but also still trying to get information. The flatter the ears, the more fearful the cat. Complete backward rotation of the ears is getting them out of harm’s way in anticipation of an attack.

When each ear is doing something different, the interpretation is more ambiguous . . . and in that moment, so is your cat’s emotional state.

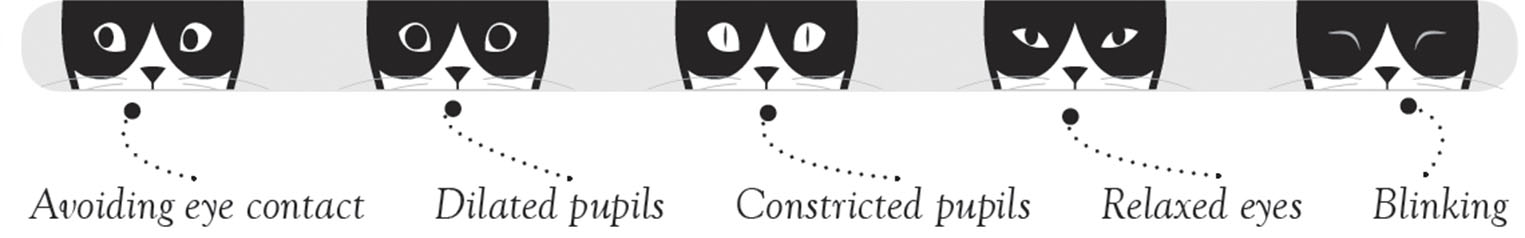

The Eyes

Pupils dilate under low light levels, but they also dilate during the fight-or-flight response. Dilated pupils let in more light and information about the environment (when cats are assessing danger, for instance, more information means securing multiple escape routes). The more dilated the pupils are, the more defensive the cat is probably feeling. On the other hand, a cat with constricted pupils is likely confident and relaxed.

However, it’s not just about what the eyes are doing; it’s also about how exactly they’re being used. A stare is usually a challenge, but a cat’s degree of focus and distractibility while staring will usually tell you how much of a “challenge” it really is.

A cat who is avoiding eye contact with another cat is typically doing so for a reason—usually to minimize the likelihood of a confrontation.

Blinking slowly is a sign of contentment and relaxation . . . which is why we try to evoke the Slow Blink when greeting or communicating with a cat. (More on this in the “Cat Greetings/Slow Blink” section in chapter 11.)

The Whiskers

The main function of whiskers is to provide tactile information to a cat. But they also provide us with some information about how relaxed or aroused a cat is.

Left: Soft whiskers

Right: Forward-pointing whiskers

A relaxed cat usually has soft whiskers that are pointing out to the side, while a fearful or defensive cat might flatten the whiskers against the sides of the face as another way of becoming “small.”

Forward-pointing whiskers indicate a cat is trying to get more information, since those whiskers will detect air movements and objects. The more forward facing the whiskers are, the more attentive the cat is. Forward whiskers could indicate that a cat is about to attack, perceives a threat, or is just plain interested, so, as always, context is important.

No single behavior or posture happens in a vacuum, so remember to consider the big picture as you evaluate your cat’s state: Is she relaxed on the couch? Staring out the window at another cat? Crouched under your bed? You also have to look at the whole enchilada—of course, that entails what’s coming from the body, tail, eyes, ears, and whiskers, along with vocalizations, but also what’s coming from the territory, the other inhabitants, even the time of day. If there’s one thing I’ve learned in translating cat language, it’s the importance of context.

Body Postures

Unlike some animals, cats don’t have clear appeasement signals, or submissive body language that says “please forgive me.” (Probably because such a thought would never occur to them!) But this communicative limitation impacts a cat’s ability to engage in conflict resolution. How can cats function in this way?

Go back to the timeline and look at how recently cats have been social—not just with humans but with each other. The ancestor cat was not a social species, and these days, domestic cats often resolve conflict through avoidance and defensive behavior, and maintain bonds through a group scent and signals like the tail up. But understanding the communicative challenges will help you understand why cats sometimes have difficulties with each other.

Cats who are upset usually take one of two routes. They can go bigger, with hair on end and an expanded posture—i.e., the classic “Halloween cat.” These cats are on full alert and may be willing to defend themselves if necessary. Straight legs, a puffed tail, and an elevated butt is a cat who is purely on the offense, essentially saying “Bring it on, I’m ready.”

Cats who make themselves smaller, on the other hand, are trying to appear unthreatening. Their ears are back, their shoulders are hunched, and they are crouching: everything is tucked in. If they get backed into a corner they will attack if they must, but that would be a last resort.

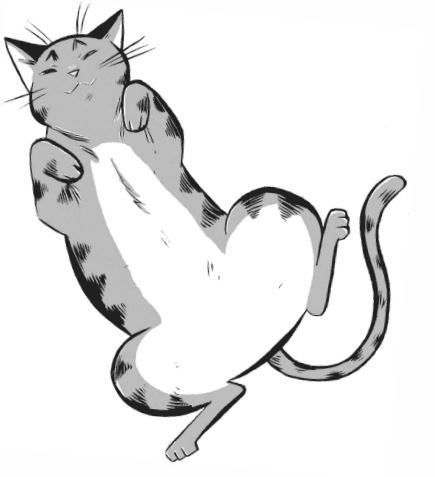

Lest you think cats are always defensive around each other, let’s be clear—cats do have friendly full-body gestures, namely rolling and rubbing. Body rolls happen when a female is in heat, but male cats roll, too. Many cats roll in response to catnip, but they also roll in the presence of other (usually older) cats. Much like the tail up signal, rolling seems to be a way to signal “I’m friendly and unthreatening.” Rolling is rarely seen during antagonistic encounters between cats.

Belly up is a play solicitation in kittens, although in adults, it could serve as a defensive posture, as their teeth and all four paws are readily available for protection in this position. Those belly-up adults are generally not interested in starting trouble, but it can indicate a willingness to defend themselves, if necessary. See the “Cat Hug” later in this chapter for more about belly-up cats.

Yawning and stretching are good signs that your cat is feeling mellow. A relaxed cat will often lay with all paws folded under the body, in what is often referred to as the Meatloaf position. All of the cat’s weapons are tucked away, and there’s no immediate intention to run or defend.

The Sphynx is another relaxed pose, where the front legs are extended in front of the body. A truly content cat will be in one of these poses with very “drowsy” eyes.

Both of these poses must be distinguished from crouching—a tense position, where a cat might be hunched over or partially propped up on the front legs. Often you will see tension in the face, or tight blinking of the eyes. In cats, this is usually a sign of pain. Because cats hide pain so well, it is important to pay attention to these subtle behaviors.

Is Your Cat Annoyed?

Many guardians think that their cat bites “apropos of nothing,” but most cats give many warnings, although these warnings may be subtle. Some cats may walk away or turn their back to you, and that is their way of removing themselves from an interaction. Or maybe you’re seeing some tail swishing, or back twitching. A paw swipe is also a warning, as if to say: “I don’t like this and you need to respect that. Next time there might be teeth or claws.”

See “Overstimulation” in section 4 for more on warning signs of irritation.

![]()

Cat Daddy Dictionary: The Cat Hug

When a cat goes belly up for you, we call this the Cat Hug, because often it’s the closest you will get to a cat actually hugging you. To fully appreciate this, you must understand the genetic experience of being a prey animal. By exposing their belly to you, they are essentially saying: “I am 100 percent vulnerable to you right now. You could take your claw and eviscerate me down this line from my throat to my groin and essentially tear me open. It is the most vulnerable part of my body, and I am flipping over and showing it to you.” Just like the body roll, it is a message of trust.

Now, is this an invitation to put your hands on your cat’s belly? No! Again, if you respect their protective instinct as a prey animal, and understand what every bone in their body is telling them, then you will appreciate the Cat Hug from a safe distance (unless you’ve already established a clear and comfortable relationship with your cat that would include belly rubs). Also, as mentioned, because this position is sometimes used as a defensive one, it’s very easy for cats to suddenly bite or scratch if they perceive your hand near their belly as a threat.

HOW THE CAT COMMUNICATES AS A SOCIAL ANIMAL: OLFACTION AND PHEROMONES

As stalk-and-rush hunters, cats don’t use their sense of smell much for hunting. In contrast to dogs, who might track prey for long distances, cats follow prey only a short distance.

But smell is critical to how cats relate to each other. Their sense of smell is approximately fourteen times as strong as ours, and it’s important to remember that olfactory information talks straight to the part of the brain that is key to emotions and motivations, such as anxiety and aggression.

Cats can also detect pheromones with their vomeronasal organ (VNO—also called the Jacobson’s organ). Pheromones are special chemical signals that reveal information about sex, reproductive status, and individual identity. You might have seen your cat make an “open mouth sniff” or grimace, which is called the Flehmen response. This behavior is a sign that a cat is taking in those pheromones (usually via the urine of other cats). From that Flehmen response, they know who has been around, when they’ve been around, and possibly even their emotional state. Are they a familiar cat? Are they an intruder? A female in heat? An intact male? Are they stressed out? This information can be used to help cats avoid contact and conflict with other cats.

Urine spray elicits a lot of sniffing in cats, especially if it is the urine of an unfamiliar cat. But strange urine doesn’t necessarily cause cats to avoid an area—it’s not necessarily a “keep out” sign.

Pheromones

Cats can leave pheromone messages through glands on their cheeks, forehead, lips, chin, tail, feet, whiskers, pads, ears, flanks, and mammary glands. Rubbing these glands against objects or individuals leaves the cat’s scent behind. The functions of all of the different pheromones are still Mojo Mysteries, but researchers have identified the functions of three facial pheromones.

One pheromone (F2) is a message from tomcats saying “I’m ready to mate.” The pheromone F3 is released during cheek or chin rubbing on objects, and helps cats claim ownership of their territory. Finally, F4 is a social pheromone to mark familiar individuals—human, cat, or other. F4 reduces the likelihood of aggression between cats and facilitates the recognition of other individuals.

How cats rub to mark can tell you a little bit about their emotional state. Cheek rubbing is generally a sign of confidence, and “head bonking” against you is a sign of “cat love.”

Scratching is another way for cats to mark their turf, but sometimes cats will also release alarm pheromones when scratching.

Urine marking is both a sexual behavior and a response to territorial changes (such as new animals or objects). While urine marking is a completely normal feline behavior, in some ways, it is the antithesis of facial marking; it’s the Napoleonic response to territorial anxiety.

WHAT MAKES CATS Raw is what unites them all; the ties that bind, however, only tell half the story. As we complete our exploration of all cats, it’s time to start digging deeper to discover what it is that makes your cat one of a kind. Now, let’s get to know your companion better. Much, much better.