11

Cat/Human Relationship Mojo

Introductions, Communications, and Your Role in the Mojo

BY THIS POINT, one thing that I hope I’ve impressed on you, especially as we dove into chapter 6 and the Mojo Toolbox, is that your life with your cat or cats is not an arrangement of ownership but a primary relationship. This very basic tenet is also the primary plank in the Cat Mojo platform. Now we’re going to dive into what it means to own the relationship at different stages of the human experience, and how the status of that relationship drives your desire to make the best life possible for both of you.

CATS AND KIDS: RAISING THE NEXT GENERATION OF CAT LOVERS

In my close to decade-long tenure at an animal shelter, I worked almost every position imaginable—which, many years later, I realize was an incredible blessing. I’ve had the horrible responsibilities associated with the pet overpopulation crisis, but at the same time, I’ve been given a periscope that allows me to scour the landscape and help chart a new course toward a more humane future.

One of my jobs along the way was director of community outreach. Although I was admittedly in the dark when it came to children, I relished the idea of being able to help instill in them a love for, and empathy toward, animals while they were at such a crucial developmental phase of their lives.

One of the more challenging aspects of life in the trenches of any movement is that . . . well, that you’re in the trench; you can’t, for the most part, know that the work you’re doing is of any value. But you know it feels good, and it feeds your soul.

Today, there’s nothing that gets me more emotional than to see children who are growing up with animals—children I meet at fund-raisers or work with in my practice. More and more, those children “get it.” They truly love their animal companions, and at the same time, they demand that others around them do the same. That radical empathy from such a young mind often brings me to tears—really! I know, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that child is going to be one more body in a growing army of compassion.

That’s one of the reasons this section is so important to me. All children should grow up with animals in their lives and learn empathy and compassion (not to mention that it’s amazing and fun and cool!). Kids should be part of raising a cat, not just as witnesses but as guardians. These kids are the next generation of cat lovers, and the reason we won’t be killing cats in shelters in the future. If you want to help ensure that your child grows up aware of the world around him, instilled with the desire to be of service, add an animal to his life.

The other reason this section hit home for me is this: far too often, I’ve noticed that when a couple is expecting a new baby—especially a first baby—their cat ends up in the shelter. The guardians are often saying good-bye before the baby is even born, and, sadly, this decision is often born out of tired old myths, the likes of which we’ll be addressing in this section.

We’ll also talk about establishing real-life preparedness for bringing home a baby to your cat, or a cat to your kids; what you can do in terms of Catification to ensure a better life for your children and your cat; and, of course, how to set the stage for your child to become a member of Team Cat Mojo twenty years from now.

CATS AND BABIES: MYTH BUSTING

If you’re expecting a baby and have a cat, you may have gotten hints from friends, family, or even your doctor that you should brace yourself for the possibility that you’ll need to “get rid of” the cat. These suggestions are largely based on myths we cling to about safety when it comes to cats and kids. Let’s start with busting some of those myths.

Myth 1: The Cat Will Suffocate the Baby

Myth 1: The Cat Will Suffocate the Baby

People still believe the myth that cats will somehow “steal a baby’s breath,” either because they are jealous of the baby, or because they are attracted to a baby’s “milk breath.”

Backstory: This myth most likely originated from an incident in the 1790s, where an infant’s death was attributed to a cat. The report stated, “It appeared, on the coroner’s inquest, that the child died in consequence of a cat sucking its breath, thereby occasioning a strangulation.”

Truth: Sadly, the infant may have suffered from something more common, such as Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, or an asthma attack—not from a cat stealing his breath.

Did you know? As mentioned in section 1, these irrational allegations were not uncommon for those times. Since cats were associated with witches back then, they were unjustly blamed for a lot of bad that happened.

Myth 2: The Cat Will Give the Baby Allergies

Myth 2: The Cat Will Give the Baby Allergies

Expecting parents wonder, Is my child going to be allergic to cats because of exposure to them when they are infants?

Truth: While some newborns could turn out to be allergic, research suggests that growing up with pets may actually help children avoid allergies. But for those children who wind up with a legitimate cat allergy, there are a number of ways to manage the issue, from air filtration to allergy shots and many stops in between. Since this landscape is quickly changing (for the better), due diligence is your best friend.

Did you know? One study showed that exposure to multiple pets (cats or dogs) during the first year of a child’s life could reduce the risk of responses to multiple allergens at the age of six or seven. A study of children who lived in urban areas (where they are at higher risk of respiratory disease) found that exposure to cat dander before one year of age was associated with fewer allergies when the children were reassessed at three years of age.

Myth 3: My Cat Will Give Me or the Baby Toxoplasmosis

Myth 3: My Cat Will Give Me or the Baby Toxoplasmosis

Due to the connection between toxoplasmosis and cats—and the misinformation about how the disease may be transmitted—many concerned parents feel it’s too risky to have a cat in the home with a pregnant mother or an infant.

Backstory: Toxoplasmosis, and the danger it presents to fetuses, has always seemed to cause waves of panic in expectant couples. A few years ago, this panic hit a fever pitch when a scientist claimed he had evidence of links between toxoplasmosis and various mental disorders. Since then, two large-scale studies that followed people from birth to adulthood found no effect of toxoplasmosis or growing up with a cat on mental health.

Truth: What’s the connection with cats? Typically, a cat eats an infected mouse or rat and the Toxoplasmosis gondii parasite lays eggs in his digestive tract, which spread to other animals via contact with the cat’s poop.

T. gondii is a common parasite. Over 60 million humans in the United States alone are believed to be infected, but for most of those who have healthy immune systems, you’d never know it. For pregnant women (or those with compromised immune systems), toxoplasmosis can be a serious health threat, and since toxoplasmosis can cross the placenta from Mom to her in utero baby, prevention is paramount.

Did you know: Toxoplasmosis is so easy to prevent that the Centers for Disease Control does not even consider being a cat guardian a risk factor for contracting it. The biggest risks? Eating undercooked meat or unwashed vegetables.

What to do: Even with this minimal risk factor, here are a few more facts and precautionary tips:

- It takes one to five days for the eggs to become infectious after being shed in the cat’s poop. If you scoop the litterbox every day, you don’t have to worry about exposure.

- Cats shed toxoplasmosis eggs for only a few days in their entire life; it’s one and done, further reducing your risks.

- To be extra safe, pregnant women should either not scoop the litterbox, or scoop daily while wearing disposable gloves.

- Indoor-only cats are rarely exposed to toxoplasmosis because they aren’t likely to eat those infected rodents. This is yet another good reason to keep your cats indoors!

Myth 4: My Cat Will Be Jealous and Pee on the Baby’s Stuff

Myth 4: My Cat Will Be Jealous and Pee on the Baby’s Stuff

When a cat pees in the nursery or on the baby’s things, we humans often presume it’s because the cat is jealous of the new addition and all of the attention that is being directed her way. Worse yet, many anticipate this behavior as part of a cat’s “jealous nature,” which then leads to unfortunate decisions being made to avoid such behavior.

Backstory: This is classic human projection, based on how human siblings sometimes respond to a newborn’s arrival into the home. So when humans observe this kind of behavior from a cat, they presume it’s because “the cat must be jealous of the newborn.”

Truth: In almost every case I’ve worked on in which a cat peed on an infant’s things, it was a territorial issue. Typically, when expectant parents prepare for their baby’s homecoming, they set up a nursery (or special “nursery area”), and bring in new objects and furnishings. These adjustments are too often deemed “off limits” to the cat, a move that backfires completely. First, it constricts the cat’s territory on two levels: by total volume, and by causing the cat’s scent to disappear from the room she’s been banished from. And then the anti–cherry on top is when the baby comes home and everything in the cat’s daily routine changes, so that everything revolves around the room she’s been banished from. A cat’s ensuing reaction is a classic Napoleonic example of “overowning”—marking key places in the nursery as a highly insecure way of claiming ownership of an area that was taken from her.

What to do: There are plenty of proactive strategies you can employ before the baby comes home to minimize or prevent this kind of thing from happening. Most revolve around having a more cat-inclusive attitude regarding the nursery areas, and acclimating your cats in advance to some of the new sights, sounds, and smells that will be turning up in their territory. We will be discussing specifics later in this chapter, in “Prepare Your Cat for the New Baby.”

Myth 5: My Cat Will Hurt the Baby

Myth 5: My Cat Will Hurt the Baby

A lot of new parents are concerned that their cat will randomly attack their baby or younger child.

Truth: Cats don’t “randomly” attack for no reason and, by and large, they don’t attack offensively; they aren’t going to make the first move, for example, and run at a target from across the room that they think at some point might be a threat. Remember—one of the things that has helped cats successfully endure as a species for this many thousands of years is that, as equal parts predator and prey, they are keenly aware of how not to pick a fight.

That said:

- Cats can attack in a defensive manner when they are cornered, if they feel their safety is threatened, or in a knee-jerk reaction to rough handling (tail pulling, etc.).

- Cats can also “respond” in a predatory or playful manner when their need for ample, energy-burning playtime (HCKE) has not been fulfilled, and there is something beckoning their hunter drive. In this case, wiggling toes under a blanket could be gleefully treated as a play target, just as much as your ankles would be as you stride across the living room floor.

What to Do: There are a few things that will help prevent these kinds of mishaps between cat and child. We’ll cover these suggestions in more detail in this section, but for now, here are the essential CliffsNotes:

- One of the first things your child should learn is empathy, respect, and proper “handling” of his feline family member. We cover this in Do’s and Don’ts a bit later in this section. Until he is old enough to learn these lessons, proper supervision is an absolute must whenever the cat is in the proximity of the baby.

- Make sure your cat has a proper outlet for the draining of her energy. The last thing you want is for your Raw Cat to be amped up to ten, with her Energetic Balloon ready to pop, while hanging out with your child who, at that moment, is moving like prey. In this case, there is a more appropriate play victim—an interactive toy!

- Try to plan cat/baby interactions when both parties are on the sleepy or mellow side. This is all about the Three Rs of your household and knowing when the energy levels are most favorable so the outcome can be positive for all parties.

THE BLUEPRINT FOR BEST FRIENDS

Our chance to build positive associations between children and cats starts before they ever meet—meaning, before your baby is even born. With every intertwining stage of human and animal parenting comes not only opportunities for enrichment and appreciation, but also significant potential roadblocks that need to be navigated. In this section, we’ll map a course through the world of cats and kids; it begins with safe boundaries, continues with planting the seeds of cornerstone values—love, compassion, and empathy—and culminates with a thriving and mutually respectful day-to-day relationship.

BEFORE THE FIRST STEP: BRINGING A BABY INTO A CAT’S HOME

Introducing a cat to a baby is in some ways similar to how we introduce cats to other furry family members. There are advance steps that can be taken along the way to get your cat acclimated to the new reality of a human sibling joining the family before it actually happens. And don’t worry—I know you’ll have a lot on your plate. Just know that whatever you can manage to do in advance will pay dividends in the transition process.

Step One: Make the Nursery a Junior Base Camp

I know it’s probably the last thing you’re thinking about as you set up a nursery while counting down the months to your new arrival, but I can’t tell you how many problems you’ll prevent by considering the needs of your cat as well as your baby. One of the best ways to initiate Cat Mojo here is to start thinking of the nursery (or designated “nursery area”) as a junior base camp.

A. Scent Soakers: Gather up any scent soakers you can find to put in the nursery so the cat and child can start mingling scents (along with yours). This doesn’t have to mean a cat bed in the crib. However, putting a cat bed or cat tree on the same side of the room as the crib is a great big hunk of Mojo.

B. Mealtime in the Nursery: Stop free feeding (if you haven’t already) and start feeding your cat meals in the nursery—their cozy new junior base camp!

C. Cat Superhighway: Consider providing a complete Cat Superhighway in the nursery. Once the baby has arrived, the cat is then able to get up in the vertical world, look down at the crib and changing station, and say, “Huh . . . is that what all the fuss is about? Is that what that strange sound is? So that’s where that smell was coming from . . . interesting. . . .” All of the observations, as well as the learning of an alien language, are done at a safe distance.

Should I Keep the Cat Out of the Crib?

Some might think that there’s a fine line between trying to keep the cat out of the crib and sending a tacit message that cat and baby shouldn’t mingle. Not so! I encourage mingling (even in the crib). Mingling is a good thing that provides indelible moments of foundational relationship building. If you consider the big picture, these mingle moments are all profit and no loss as long as these visits are supervised.

That said, if you build a Cat Superhighway and have some other elevated space for your cat to traverse, the crib becomes not the most interesting place in the nursery for the cat to be, and that’s a good thing. Of course, I’m not saying we will ever be able to eliminate the crib as a destination—it’s soft, it’s somewhat of a cocoon, and between the baby and the bedding, it’s a nice warm spot—but with Catification on board, it won’t be the only one. Conversely, if you have no cat furniture or vertical space to claim ownership of in the nursery, your cat will rightfully think that the crib is the new bed you got for them.

At the end of the day, though, it’s about your comfort level, and it’s your call on how you want to raise your baby and your cat. If you decide to say “no” to the cat being in the crib, bear in mind all I’ve said about the territorial importance of the nursery—and make sure to give the cat a “yes” somewhere else!

Step Two: Desensitize Your Cat to the Sounds and Scents of a Baby

Now that you’ve welcomed your cat into the nursery, it’s time to introduce him to sounds and scents that are part of the baby package deal. We’re going to use a well-known process known as desensitization—which is commonly used in human therapy to help people with fears and phobias. It works with our companion animals, too.

Desensitization is helping an animal become less sensitive to something that is potentially unpleasant (such as the sound of crying babies) through repeated exposure at a “safe level” that you gradually increase in intensity. The bonus technique is called counterconditioning, and that is when you change your cat’s emotional response from potentially negative to positive by pairing that unpleasant something with things he likes, such as treats or play. Let’s put it into action.

Sounds: Strange as it may seem, there are plenty of recordings of babies screaming, crying, gurgling, and laughing available online. It’s a great idea to get your cat used to some of these sounds before the baby arrives. And here’s an interesting little fact: regardless of species, most mammalian distress calls happen to be similar in pitch, which means that those baby cries might trigger an alarm response in your cat. In other words, desensitizing to these sounds is a classic “better safe than sorry” scenario!

- First, use a version of Eat Play Love to find your cat’s Challenge Line, by playing the recording softly as you feed a meal or Jackpot! Treats. Or, if the cat is more play motivated, engage him with his favorite toy. Make sure your cat is absorbed in this activity, enough so that the sound is not a distraction.

- With each EPL session, creep the volume up, taking note as to when the primary activity starts to get clouded by distraction, anxiety, or fear. At what point do the cat’s ears start to move, does the fur on his back begin to twitch, or does he begin to demonstrate any kind of tension, including looking around the room? Does he completely abandon ship from the activity, deciding that the risk he is exposing himself to is just too great?

- That fine line between comfort and challenge—in this case, the volume that begins to make your cat uncomfortable—is your cat’s Challenge Line. Once you identify the Challenge Line, you can desensitize your cat to it, by turning the volume down, then slowly trying to inch it up again until your cat is desensitized to the sound. Then you can start again at a higher volume.

Scents: Expectant moms often know other moms. If you can bring home blankets or clothing that smell like a baby, even if they don’t smell exactly like your baby will, you can introduce that very distinctive scent to your cat early on. Let your cat explore the blankets at his own pace. You can place treats nearby, but never force a cat to get close to the baby blankets. There is a school of thought that would have you actually rub the blankets on the cat as a way of introduction. Make no mistake—whatever school that is, it’s not mine!

There’s no way to guarantee that when you bring your cat and newborn together, your cat is going to be all unicorns and rainbows about it, but if he’s allowed to survey the weird before attempting to interact with the weird, it will be, well, less weird.

Step Three: Three Rs—Before and After

We want to start co-constructing the Three Rs (Routines, Rituals, and Rhythm) around cat and baby, even before the baby shows up. In this case, you will go through an HCKE session (chapter 7) with your cat as you normally would. But the twist is this: conclude the session by leading the cat into the nursery for mealtime. This will reinforce positive associations with this “new” space, and also help to develop a seamless flow from the familiar territory of the house to the new or revamped territory of the nursery. This will also help to define the new routine, ritual, and rhythm of mealtime in the household once the baby shows up.

Why is this important to establish before the baby arrives? Sleep will be at a premium, and the pressures of caring for a newborn are momentous. If you don’t actually build these concrete Three Rs in advance, you’ll find yourself facing a slippery slope that unfortunately I’ve seen some of the most well-intentioned new parents slide down. It begins with exhaustion, then leads to less integration and more separation. Your cat, of course, responds to the separation negatively. If you restrict cats from that territory, they get insecure about it; if you let them in without the right preparation, they may pee on things or hiss at the child. So you might end up locking them out more, but now they’re peeing everywhere else more. You have inadvertently broken down the bond between you and your cat. You can avoid this.

Building the Three Rs has a key focal point, just like the ones we build when introducing a new animal into the home: mealtime! Therefore, I recommend feeding the cat in the nursery when you’re feeding your child. This gives you the invaluable opportunity to be as inclusive as possible; as you build rituals around your baby, build your cat into those rituals. While you’re sitting in your rocking chair nursing your child, what better time to feed meals to your cat?

Bringing a Cat into a Child’s Home

If you already have kids and you’re thinking of adopting a cat (or two), there are a few things you can do to help ensure a successful relationship. You’ll notice this process tends to be a bit simpler than bringing a new baby into a home where a cat is already established, since you’re not having to “shake up” your cat’s territorial certainty.

Choosing Your Cat

The Energy Match: When you’re at the shelter, foster home, or rescue agency, try to match energy to energy, just like you would if you were bringing home a new cat for a resident cat. If your kids are younger and/or rambunctious and active—and you have lots of other kids visiting—look for a Mojito cat: perhaps a teen or adolescent who is ready for nonstop fun. They can be a great match for an active household.

History with Kids: A cat who has a positive history with kids would also be ideal, because then you’ll know she isn’t going to be overwhelmed by the hustle and bustle of a home with several kids running through it.

Older vs. Younger: An older cat may be better suited for a more mellow home, or or one with teenagers who are a bit more chill. While we are often drawn to kittens because they are so damn cute, just keep in mind that they are fragile, and need much more supervision, both for their own sake and for that of any small children.

Preparing for Your New Cat

Set Up Base Camp for Your New Arrival: As a family, you can plan out setting up that room, and what kinds of scent soakers you’d like to arrange for, etc.

Basic Catification: As mentioned earlier, your new cat will immediately see and evaluate her new home vertically. Make sure she has some “higher up” places to traverse, especially if there are some enthusiastic, high-energy children in the house from whom the cat might need to take a break!

Initial Introductions: Once you bring the new cat home and get her set up in base camp, let her settle in for a bit before meeting anyone. Then later, when introducing the cat to your family members, do it supervised and one at a time. If there are multiple children all seeking the cat’s attention and getting excited about their new animal brother or sister, it will most definitely scare the newcomer, at the very least. It’s never too early to exert control and help dictate the tone and tempo of their relationship.

THE NEXT STEP AFTER THE FIRST STEP: CATS AND TODDLERS (A.K.A. KIDZILLA)

One fascinating element of cat communication is the language expressed through spatial recognition and respect. This is why I spend so much time on the traffic flow element of Catification (chapter 8). Especially in the shared horizontal world (the floor), we see the dynamics of territorial co-ownership—one cat who hugs the wall yields power to another who gets the center lane of traffic, or they may time-share prized scent soakers and signposts and resources like beds that mark the movement of the sun throughout the house. It reminds us that every position is a potential move in Cat Chess; a lot of these moves are subtle, and not completely understood by us, but as cats pass each other in the most delicate of ballets, we know without a doubt that this language is written in the Raw Cat’s DNA.

And then . . . Kidzilla enters the living room like it is downtown Tokyo, and turns the ballet into a mosh pit.

On average, babies take their first steps at between nine and eleven months, and by fifteen months they are fully cruising/toddling/walking/wreaking havoc. In the carefully choreographed landscape of cat urban planning, there may be no disruptive force quite like Kidzilla. Why? Not just because of the unpredictable movements, nor the fact that he or she ignores all traffic signals, moving with gleeful abandon through the center of the room, cornering unsuspecting Wallflowers and thumbing a nose at overowning Napoleons. No, the true threat resides in the total lack of self-consciousness. Kidzillas don’t know where they want to go. Really. They don’t have the developmental skills to navigate left or right in a quasi-straight line or the communicative skills to back off if they terrify the four-legged family members. There is no adherence to the rules of Cat Chess. You know that look on your cat’s face—the “Oh god . . . what is that?” look—as she realizes there are no escape routes. Kidzilla is closing in, and the fight-or-flight alarm bells sound.

If you have not already invested in Catification, this is that moment. You should be measuring just how far up your child can reach, and then build your Cat Superhighway up from there. Your cats have to know that they have somewhere in the vertical territory that is safe.

As mentioned in the Myth Busting section of this chapter, cats are not naturally offensive; however, they may become defensive when their exit routes are cut off . . . which is to say that the only reason they’ll “go after” the Kidzilla is because they perceive that Kidzilla is coming after them! Don’t wait for this potentially explosive situation to happen; if you subscribe to proactive Catification before your baby is born—or just prior to bringing a new cat into a home with youngsters—you’ll be in a much better place . . . and so will the cats.

Your ultimate goal at this age range is to have territory within the territory that belongs to the cat and gives the cat a childproof vantage point while giving the child a cat-proof vantage point.

Putting the Super in Supervised Visits

Good Catification will keep any inadvertent child/cat encounters to a minimum and, as discussed, provide your cat with a necessary escape route if need be. But what about some planned time for your child to interact with the cat, or vice versa? Three things:

- When your child is in this toddler age range, it is imperative that all “official” interactions between child and cat be supervised. No exceptions, please!

- It is best to plan for these supervised interactions at “lower-energy” times in the household, when both cat and child are at their mellowest. This might be after a play session with your cat, when his energy has been expended, and/or near bedtime or naptime for the child.

- Touching, for children this age, is what they are all about. Remember, however, that their motor skills are not fully developed, nor is their sense of what may or may not hurt an animal. Supervision also means allowing them to pet with your hand guiding, so you can stop the hands from grabbing and pulling, and, in general, avoid a hiss and scratch response.

LITTERBOX ENLIGHTENMENT

The second your child can toddle and you can lose track of him, you should be worried about him going into the litterbox. The box represents ground zero for the best- or worst-case scenario of cat/kid introductions simply because it is a primary destination for both partners in the dance. Of course, for cats, it is the epicenter of activity and identity; for Kidzilla, it’s a playground. Watch out for the classic anti-Mojo move here, which is to reflexively think, “I definitely do not want my kid getting in the litterbox . . .” and off all the boxes go into territorial exile—the garage, the mudroom, the laundry room, or the unfinished basement where the child won’t get to them. This, of course, violates one of my most sacred tenets when it comes to litterboxes and Catification; you wind up subtracting Mojo from the equation in the name of what might happen.

Another example of this Mojo subtraction is taking existing litterboxes, disguising them as something else, putting lids on them, and facing the opening of that box toward the wall in an attempt to dissuade your child from getting into them.

Hint: A decorative shoji screen can create a barrier to the box, or you can use a high-sided box with a small entryway cut in it. If you find yourself leaning toward the avoidance side of the coin, making baby-related “what if?” changes based on your aesthetic instead of on what will work best for cat and kid, remember: payback is a bitch.

On the toddler side of the coin: if your child is dying to play in the litterbox, give her other things to play with. Whether animal or human, the No/Yes works for everyone. You don’t want to remove the most important component of a cat’s territory in the name of what might happen.

![]()

Cat Daddy Tip

You can use a baby gate, raised up eight or so inches off the floor, so at least you’re not hiding the litterbox. That way, the cat can get underneath or over the gate, and your baby can’t get through either way. There are also pet gates with cat doors in them, which get the job done with minimal guardian hurdles to jump.

One concession to be made on the feline side of this Catification conundrum: if the baby tends to play in the living room, maybe the litterbox should be in the bathroom or bedroom—rooms to which the baby won’t make her way unsupervised. However, conundrums provide great opportunities to put your imagination to the test; for instance, although ordinarily you might think this an absurd idea, raising the litterbox off the ground is absolutely fine by most cats (if they are agile). If you can live with it, remember, it succeeds in keeping your cat Mojo-fied and your child out of the box.

The upshot of all this is that I don’t have a hard and fast rule for this potential roadblock—because we are in the world of cat/kid compromise. Anything goes as long as you try to adhere to the rules of Catification, and keep your kids from seeing a litterbox as an engraved invitation.

For the cats’ sake, all I’m asking you to do is not give up and make the litterboxes completely unappealing for the cats, or put them all in the garage . . . or the garbage.

THE THREE RS REMINDER

By now, your family will have fallen into a certain rise-and-fall pattern of energy cycles, based solely on the particulars of your household activities. As discussed in chapter 7, you will want to establish key rituals and routines with your kids and cat, and base them all on your home’s natural energy spikes. This creates your unique home rhythm.

Earlier in this chapter, we described the routine and ritual of feeding the cat while feeding your baby in the nursery, to create a particular household rhythm. But as your child grows older, your Three Rs will evolve, and you’ll find other ways of intertwining the various routines and rituals, so that your evolving family rhythm stays in sync. This will make all of your various “times”—mealtime, playtime, bedtime—rise, fall, and flow like a Beethoven symphony.

The last word on this topic: the making of all beautiful music requires the willingness to make hard choices. Whether it comes to the temptation to close off the nursery or access to litterboxes from your cat, I would encourage you to make the opposite choice; figure out what makes the choice risky, examine your hesitation or even fear . . . and run straight at it!

MATURING MOJO: EARLY CHILDHOOD AND THE CLOSING OF THE CAT GAP

Much of what the parental role is in the early years of cat/child relations falls somewhere between a diplomat and a referee. We are attempting to protect one from the inadvertent actions or reactions of the other, all while fostering a common respect and reverence between them. Once the child gets beyond the toddler years and is better able to take direction, we can begin to instill those key foundational, Mojo-building do’s and don’ts that will set the two on a lifelong course as the best of friends.

ANIMALS ALSO FEEL EMOTIONS

Empathy and respect are two of the most prized Cat Mojo virtues that children could ever learn when it comes to their relationship with cats. At around the age of three or four, children are starting to put words to their own emotions. They can answer questions like “What does it feel like when you’re scared or happy?” This is also the age when kids start to understand other people’s emotions, too. They are beginning to understand that other individuals have their own thoughts and feelings (an ability known as theory of mind).

The more similar to herself your child can perceive your cat to be, the more accurately she can identify your cat’s emotions. She won’t be able to take it much further yet, but you can still help her draw parallels. For instance, you can ask, “When scary things happen sometimes, how do you feel?” and whatever the answer is, you can say, “And do you think that when scary things happen, Fluffy feels the same way?” Of course, discussing positive feelings works wonderfully, too. For instance, “How do you feel when we go ride the merry-go-round?” and, whatever the answer is, “Do you think Fluffy feels that way when we play with her?”

From there, you can use the same kind of dialogue to talk about comfort, love, and physical pain. These questions, and the way you guide your child’s answers, are the roots of empathy and the cornerstones for deep relationships with animals down the road.

CAT DADDY DO’S

Model Compassionate Interaction

- First, use a stuffed animal to demonstrate how to handle a cat: explain that we don’t pull the tail or ears, and that we pet gently. If your child is rough with the stuffed animal, ask him to pretend he is your cat, and to tell you how he thinks he would feel if someone treated him in such a rough manner.

- Next, teach your child how to let the cat “pet” him, and where most cats like being petted the most, which is usually around the cheeks (for more on this read about the Michelangelo technique on page 232).

- You should already know what kind of petting your cat appreciates, but with most young children, one-finger petting or petting with an open hand are safest. This is also a great time for kids to learn that most cats are not wild about repeated head-to-tail pets (which is not necessarily true for all cats, but avoiding this type of petting helps to avoid petting-induced overstimulation. May as well stay one step ahead of the game!)

Remember: You can’t blame a young child for wanting to grab, and you can’t blame a cat for wanting to get away. But a lot of cats get only one strike before they are out, so you can supervise, give direction, and model good behavior to help your child be more gentle with the cat.

Teach kids to always talk softly and gently to the kitty: No yelling or loud, excitable talking at, or around, the cat.

Teach proper language—your cat isn’t an IT. I feel that this “do” is one of the most important because it addresses the big picture, and helps to cement what we hope to be the most compassionate generation in history. Hyperbole? No way! Internalizing the concept that an “IT” is a suitcase or a baseball, not an animal with a beating heart and emotions, will help tip the no-kill scales in our favor (and, of course, in favor of millions of cats). Plus, when it comes to the smaller picture, i.e., your cat, it will help her get treated in the way I’ve been discussing here. So, always refer to your cat by name or at least gender, and encourage your child to do the same.

CAT DADDY DON’TS

Never be rough—ever: No hitting, spanking, “patting,” or backwards petting (against the direction of the cat’s fur).

Respect the “personal space bubble”: Don’t disturb the cats when they are eating, sleeping, using the litterbox, cocooning, or in their vertical space.

Hands are not toys: It’s never too early to teach this. We can’t count how many cats wind up in shelters thinking hands are toys, and that ends up being a huge strike against them for getting adopted. Be consistent and use toys for play. Hands should be for holding the other end of an interactive toy—which is tons more fun than having your hand scratched up anyway, right?

Teaching Kids the Basics of Cat Body Language and Vocalizations

As I’ve been highlighting throughout, teaching kids to develop their own sense of empathy (just as you’ve done in becoming the Cat Mojo Toolbox) is a more organic process than just giving them a list of do’s and don’ts. By tapping into their sense of how they would feel about and respond to certain situations, the talk about how to approach cats, and when not to approach them, becomes easier. For example, if the cat’s tail is swishing, her eyes are big, or her ears are flat, these are all indications that she is not feeling especially sociable at the moment. A low growl, a moaning vocalization, and of course a hiss or a spit (whether it signals fear or agitation is inconsequential) are fair warning!

For more information, humaneeducation.org is a great resource.

MORE MOJO-BOOSTING IDEAS FOR KIDS

If you’re wanting to get the kids more proactively involved with your cat’s life, that’s great! Here are a few ideas:

Things young kids can do with or for cats:

- Have your child help with feeding so that your cat associates him with great things.

- Your child can tend a cat garden; he can grow herbs such as parsley, sage, or catnip. Nowadays, there are plenty of easy-to-use kits available.

- Young children can play with the cat using an interactive toy once they have some motor control—but no earlier than that, because they can all too easily move a toy too fast and scare the cat (not to mention that a simple fishing pole toy can resemble a medieval weapon). That said, with parental supervision and guidance, interactive play can be a great way to engage both cat and kid, and can be an amazing educational tool about the nature of the Raw Cat.

CAN KIDS HELP TO TAKE CARE OF THE CAT?

A lot of parents want to teach their children responsibility by giving them chores related to taking care of a companion animal. It’s great for children to understand the idea of being responsible for another’s life, and the concept of guardianship and being a pet parent. We just have to keep in mind what is reasonable and what is setting them up for failure.

A child’s level of responsibility for a cat’s care depends on the parents. You should communicate with your children about what needs your cat has. Help them see that their needs and their cat’s needs are not that different. Being a good friend to their animal means providing their cat with a clean bed and litterbox. Cats need food, water, a warm and dry place to stay, and an animal doctor to go to when they are sick.

Should a six-year-old be scooping a litterbox? It depends on the child. But generally you can at least have your child assist you with the food, water, and litterbox duties.

Again, day-to-day life provides plentiful and wonderful opportunities to reinforce empathy. Keep reminding your child that this is not simply a chore, but a way to show your cat how much you love him. After all, this is what a parent does; we demonstrate how much we love our family members by taking care of them, feeding them, keeping their rooms clean, etc.

BEST OF FRIENDS FOR A LIFETIME: YOUR ROLE IN THE MOJO

One of the reasons I loved telling you all about your Cat Mojo Toolbox in chapter 6 is that once the concept becomes more than a concept, once it is a part of you that you can call upon, it becomes a gift for others, and I don’t just mean the animals in your life; the toolbox is a gift to be passed down to your kids.

Cultivating their own toolbox also makes it much simpler to reiterate one of the foundational points of Total Cat Mojo to your kids: you are in a relationship with your cat. So you are not providing them an education just on animals, but on the concept and nature of relationships. They learn how to listen with compassion and how to act toward another as if it matters to their own life. They will also be better grounded in the notion that the quality of relationships (with other humans or animals) will hinge largely on two things: how well you communicate with them, and how accurately you can interpret and better respond to what they’re communicating to you.

In the case of our relationship with cats, this process can be uniquely complex, as it will involve both spoken and unspoken communication—and, let’s not forget that the language being received is a completely foreign one. Spoken communication is (obviously) all about the words you use to communicate to your cat, and also about the words you use to internally define the various communications your cat is transmitting back to you. You might be tempted to think, “How could any of this matter? My cat doesn’t know what I’m saying, let alone thinking.” Aahhh, but know, they do.

Unspoken communication is more about the overall “vibe” you’re projecting—body language, emotion, gestures—and what we often perceive to be the “harmless intangibles” we carry around in the presence of our beloved cat, not thinking they would even notice. Aahhh, but notice, they do.

In the case of both spoken and unspoken communication, there is an ongoing dialogue that you are having with your cat, around the clock, that she not only is aware of, but is often responding to. Therefore, the Total Cat Mojo factor in our relationship with our cat is largely on us.

In this next section, I will reveal a handful of the most important ideas that I’ve learned over the years that we can embrace, and actions we can take, to help ensure a thriving, long-term relationship with our feline family members.

HUMAN EMOTION AND BODY LANGUAGE

Cats feed off of human emotion, and this is largely displayed, subconsciously or otherwise, by body language. Cats will mirror your energy, and if that energy is frenetic, it takes just a single spark to set them off. For example, if you are fearful, tentative, hovering or hunching over them, cats will sense that you don’t trust them. Or if you are supernervous when you are petting a cat and jerk your hands away, he might perceive this as prey running away, causing this simple, unconfident gesture to lead to a misunderstanding, and maybe even a bite or a swat.

So, how should you approach a cat you’re either just getting to know or who is a bit skittish? First, put your fear aside; when guardians are confident, that positive energy feeds off of itself. It’s all about energetics, and you need to come from a place of stillness and calm. Be a nonthreatening ambassador, and carry a friendly message, entering feline territory with quiet confidence. This is especially true in the face of Wallflowers or Napoleons, who are just looking for an excuse to either run away or make a power play.

Another way of saying this is that for the most part, the best way to approach a cat is just to ignore them. This is especially true with fearful cats. Back off, get low (meaning off your feet, not hovering over the top of them), and let them come to you. Have you ever thought about the fact that in a room full of people that cats have never met, it’s not the ones who identify themselves as “cat people” that the cats are attracted to? It’s the ones who are either allergic or who identify as “cat haters” or “dog people.” Because, in not wanting anything to do with the cats, those humans have opened themselves up to being scoped out and explored by the cats, who, at the same time, are avoiding and dodging the hands and forward-leaning bodies of those who are busy trying to convince you that “ALL cats LOVE me!”

CAT GREETINGS

CAT GREETINGS

Let’s take a closer look at the subtle art of the cat greeting, starting with one of my all-time favorites. This one will work anytime you meet a new cat, and also as a reliable way to communicate good Mojo to your own cat.

The Slow Blink (a.k.a. the “Cat I Love You”)

Cat behaviorist and author of The Natural Cat Anitra Frazier learned, perfected, and wrote about a technique she called the “Cat I Love You,” just by looking at cats in windows on the streets of New York. She observed that, when approaching, if she softened her face and gazed at the cats, the cats would slowly blink at her. She took this as a cue and began initiating this when approaching—and the cats, or at least the vast majority of them, would blink back. Using this discovery with her cat clients, many of whom were traumatized, anxious, aggressive, or flat-out untrusting and scared, she found that the blink was a Rosetta Stone, an “in” to the hieroglyphic nature of cat language.

So why is it called the “I Love You”? In my opinion, it’s because this moment is rooted in demonstrating trust through vulnerability. Remember, cats are also prey animals, and slowly closing their eyes to you is not something they would naturally do. In the wild, it’s in their wiring to “sleep with one eye open,” 24/7. So to close their eyes to an “unknown entity,” a potential aggressor, is the ultimate show of vulnerability, trust, and, therefore—in the language of the predatory world—love.

We humans can return that vulnerability by offering this reciprocal display of trust. When I do the Slow Blink to a cat client, especially a hyperaggressive one, I’m essentially saying, “You could scratch my eyes out right now, but I trust that you won’t.” I generally start with the Slow Blink as an initial greeting to a cat because I need to demonstrate, right off the bat, that I am truly vulnerable (which cats know; you just can’t lie through your body language to a cat, any more than you can verbally lie to a polygraph machine). This demonstration of trust is key. (Conversely, staring into the eyes of a prey animal like a cat can elicit a fight-or-flight response—the last thing you want when you’re trying to build trust and make friends.)

When practicing the Slow Blink, make sure you keep your eyes “soft” and simply gaze, as opposed to stare. There’s a very subtle but very important distinction to make between gazing and staring. Go look in a mirror right now and try both. You’ll notice that a gaze is light, relaxed, nonconfrontational, and will set up the trusting Slow Blink; a stare is uneasy, obtrusive, confrontational, and will possibly set up a claw to your face if it’s a strange cat who is already feeling threatened. Focus on your cheek muscles, your jaw, even your neck and brow. Before meeting, if you are the least bit unconfident, try a progressive relaxation exercise in which, for instance, you raise your eyebrows to the ceiling, hold them there for a ten count, then release. Do that for all of the muscle groups from the shoulders up, and you should soon be in a place of physical neutrality.

Now try it with your cat: Gaze at her, soften your eyes, blink, and think, “I love you.” “I” with eyes open, “Love,” eyes closed, “You,” eyes open. Wait for an eye blink back, or at least for her whiskers to go neutral. Even a partial return of the Slow Blink is a good sign. If you don’t get a blink in return, look away or down, and try again.

Of course, some cats just don’t return the blink, and for others, it’s about proximity, and you may need to step back a few and try again. The point is, it’s about learning a new language (for the human), so don’t take it personally if you aren’t getting the response you desire; at the very least, you both learn something very valuable about the other, and that “in,” that Rosetta Stone, still exists between you.

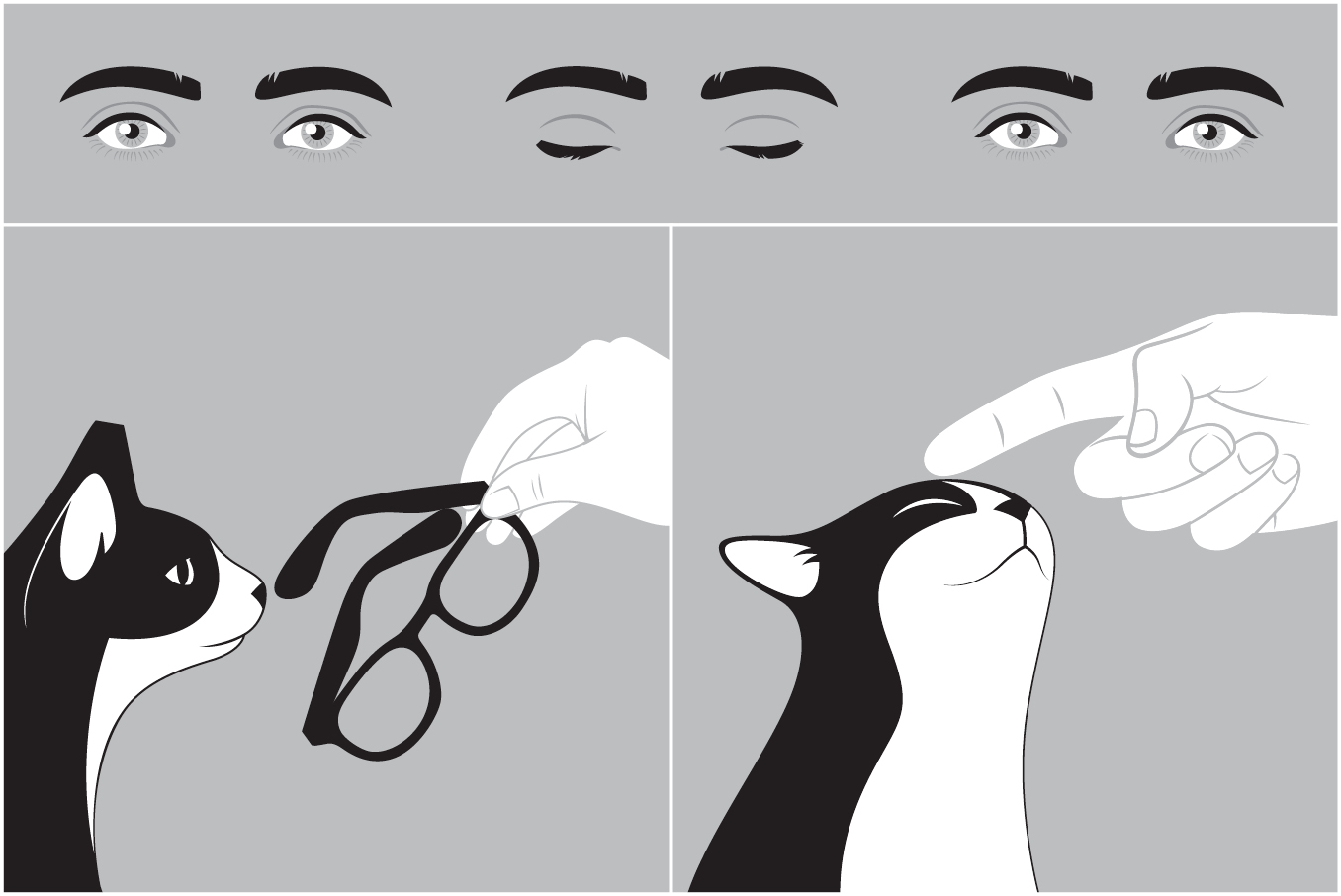

Three-Step Handshake

Many years ago, I was thrown into a situation in which I had to kind of intuit what I call the Three-Step Handshake. I was working at an animal shelter, and a woman had just dropped off a young cat who had been hit by a car. She couldn’t afford his treatment, and, honestly, it didn’t seem like she wanted him anymore. When she handed his carrier off to me, I knew he was in pain and needed to be rushed to the vet clinic.

In case you can’t see where this story is going, I ended up adopting this cat and, as I chronicled in my memoir, Cat Daddy, he basically saved my life. But my first face-to-face with Benny required me to think on my feet about how I was going to let this injured and terrified cat know that I was there to help him.

I think of this as being an ambassador to a foreign country that has been isolated from negotiations and trade. The citizens are suspicious and wary, and have every reason to be. The same was true for Benny. He had no reason to trust me, so I had to give him one.

As he was sizing up his situation (“I’m in pain, strange human, I’m stuck in a box, trapped in a moving vehicle . . .”), I was thinking about what I could bring to the table—a peace offering that would be more than just a truce between two countries to not bomb the crap out of each other. It had to say, “I carry a friendly message.” I started with that Slow Blink, but I wanted to strengthen that message.

Knowing that scent is so important to cats getting to know each other, I also tried offering Benny the earpiece of my glasses—something that smelled strongly and distinctly of me, and that I could present at a less-threatening distance. When he responded positively and rubbed into the earpiece, complementing my scent with his, I next offered my finger to that space above the bridge of his nose: the feline “third eye.”

Bingo! He pushed his cheeks into my finger and just relaxed right into that touch. And that was the moment I knew that these three different techniques could be combined into the equivalent of a handshake that thaws a chilled relationship between two countries. This was my diplomatic gesture that made us allies.

So, to review, the Three-Step Handshake breaks down like this:

Step 1—The Slow Blink: Present yourself in a completely nonthreatening way to the cat.

Step 2—The Scent Offering: Offer the cat something that smells like you. I like to use the earpiece of my glasses or a pen.

Step 3—The One-Finger “Handshake”: Offer your hand to the cat in a relaxed way. Take one finger and let the cat sniff it like he did the glasses or pen, and bring that finger toward the spot between and just above the eyes. Allow him to push into your finger; he will press in so you can gently rub his nose and up to the forehead (a more in-depth exploration of this technique in a moment).

Let Your Cat Call the Shots

One study looked at over 6,000 interactions between humans and their cats in 158 households. The interactions were categorized by whether the human approached the cat or the cat approached the human. When humans initiated contact with their cat, interactions were shorter. When cats were allowed to initiate the contact with their human, interactions lasted longer and were more positive.

TEACHER’S PET: A FEW GUIDELINES

Petting is one of those things I feel conflicted about when offering up a full-on tutorial. The act of petting is, to a degree, a very individual experience—an expression of the relationship you have with an individual cat. Still, approaching that experience with “Toolbox Thinking” will allow you to figure out soon enough how, where, and for how long your cat likes to be petted. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve offered up universal “rules of engagement” like “Don’t pet the belly!” only to be told in return that the cat in question absolutely loves it.

Just like the Three-Step Handshake and the Slow Blink, there are some techniques I always fall back on when it comes to petting a cat I’ve just met. I never want to make assumptions about where (or if) a cat wants to be touched. Here are my go-to guidelines:

- The best introductions are made by asking, not telling. When a cat walks up to you, greeting him with a full head-to-tail stroke is just rude, and expecting entirely too much. Instead, I rely on the Michelangelo (a.k.a. the Finger-Nose technique). I’ll use this technique if I’m seated on a chair and a cat comes to explore me, or if I encounter a cat while standing and he is in a vertical place (i.e., not on the ground). As the cat approaches, I will allow my hand to relax and, palm down, extend my pointer finger—not extended rigid, but relaxed, so that it almost seems to be coming off my hand like an upside-down “U.” This presents the tip of my finger in a way that’s similar to the way one cat might present his nose to another’s. Touching noses is a universally friendly gesture between cats, so I’m just trying to let that greeting happen.

- Whether I get the green light from the Michelangelo technique, or just initiate petting with a cat that I already know, the beginning of that session always begins with Letting the Cat Pet You: As soon as that “nose-to-nose touch” is accomplished, I straighten out my finger to provide just a little pressure to the touch. If the cat is feeling affectionate at this point, he will push the bridge of his nose into my finger. From there, he will give you direction—up toward the forehead, side toward the cheek. Just go where he tells you and you can’t go wrong. It’s all about listening!

- The universal places I usually assume I can pet are: the cheeks, chin, and forehead. I see these as Gateway Touches. Gaining trust and eliciting a pleasurable response from these areas allow me to know if petting below the shoulder will also be a good thing for both of us.

- The next technique is one I call the Assisted Groom. This is one I use once I’ve moved past some of the other more introductory moves, and there’s a bit of trust inherent in my touch. Knowing that grooming is not only a built-in need but also a self-soother for a cat—something that, if she is feeling stressed or anxious, helps her calm down—I use my finger to simulate the action. Beyond just being pleasurable, it really helps cement the bond between us. I’ll start with almost an extension move from Finger-Nose: the finger goes from nose to side of mouth/cheek. I will inevitably get some of the cat’s saliva on my finger from that move from nose to tracing the mouth, so I will continue by taking that finger and tracing the bridge of the nose between the eyes and up to forehead to nape of neck. Many times when I present my finger initially doing the Michelangelo, the cat will lick my finger. Again, I will use that finger to spread her own scent around the areas that are already scent gland–heavy (cheek, forehead, etc.). Sure, it might sound a little . . . out of the ordinary? But try it and you’ll see why I do it.

- Another “advanced Mojo” move is Hypno-Ear: I call this advanced because, like the Assisted Groom, there’s a measure of trust that needs to be gained before attempting it. I call this “hypno” because if done right, it absolutely gets the cat into a bit of a zombie-fied state. All it involves is a circular massage with the thumb on the inside and finger on the outside of the ear. The top two-thirds of the ear is definitely the most sensitive part. In terms of the exact spot and speed of the circles, as always, it comes down to the individual. I can say, though, that the pressure is not tickle-light, but rather a medium pressure.

We would be doing cats a disservice if we said that all cats like to be petted in certain areas, or hate certain types of petting, so get to know your cat’s preferences. Once you do, the main thing you’ll need to concern yourself with is whether or not your cat is prone to overstimulation.

Overstimulation is a form of aggression that occurs when your cat passes a threshold for interaction. Petting-induced overstimulation is the most common form, although sounds and pain, and just general energetic chaos, can also take your cat over the edge.

RECOGNIZING, PREVENTING, AND MANAGING OVERSTIMULATION

I know I’m about to date myself here, but do you remember the commercials with the Tootsie Pop owl? He conducts a highly scientific test to find out how many licks it takes to get to the center of a Tootsie Pop? (One . . . two . . . three . . . CRUNCH!) Similarly, you’ll want to take a sort of petting inventory to see if your cat is an “overstimulator.” Of course, it would be a whole lot better if you could determine your cat’s threshold before the “CRUNCH”—which, in this case, would probably be a swipe or bite to your hand. Here are a few suggestions for navigating overstimulation:

Recognizing Symptoms

Since cats who get overstimulated tend to have their own unique recipe for what causes it, your astute observation will be key here. Here are a few “tell-tail” signs (sorry, couldn’t help myself). Much of the time, these types of behavior are somewhat out of character for your cat.

- Dilated pupils

- Piloerection (hairs on end)

- Ears back

- Quick head turns

- Licking, rubbing, or other affection that becomes too exuberant

- Tail swishing—usually means that the Energetic Balloon is ready to pop. As the tail goes from an intermittent twitch to a swish, things are increasing in intensity. Unchecked, this behavior will finally graduate to wagging like a happy dog . . . except they are not dogs, and they are definitely not happy! At this point—right before the pop—it’s like your cat is screaming at you.

- Back Lightning is a type of twitching that happens through their back that is, at least partially, a spasm, but also a way of getting that energy out. You may notice your cat walking across the room, then suddenly stopping as if a fly just landed on him, and then very deliberately grooming himself. This self-soother is also a self-regulator. It’s also a reliable indicator to you that your cat’s energy tank is just about topped off.

Preventing the “Blowup”

Be aware of energy in—For some cats, petting is air into the Energetic Balloon in a way that is intolerable. Energy in without any means of release fills them with a sort of static . . . and then finally . . . bang! What might feel good for three to thirty seconds suddenly feels like it’s going to make their balloon pop. That hiss, that bite, their turning on you, running away, or self-grooming are all desperate attempts to let air out of the balloon. Think of these behaviors as engaging a sort of safety valve in the balloon. Be aware! For other cats, extreme enjoyment may actually trigger overstimulation—especially if you’re petting in an energetic way, with heavier than normal pressure or faster than normal tempo. You might notice the cat bringing her tail up to meet your hand in an equally excited way.

Take an inventory—Note what happens when you touch certain areas of your cat’s body. Try stroking the tail alone, then a full-body, head-to-tail stroke. Now a belly touch, handling paws, head, cheeks, and shoulders. Note the difference between petting once, twice, three times. How many full-body strokes can you give your cat before you tend to incite overstimulation? And most important, if your cat gets overstimulated, what was the obvious thing that caused it, the straw that broke the camel’s back?

It’s sometimes hard to think of ending your petting session because it’s obvious that the cat is enjoying herself, but you are tempting the Tootsie Pop CRUNCH! If you are mindful of these changes and notice these signs and stop, the aggression—which we tend to call an “attack”—simply won’t happen.

Managing Energy

Try to regulate your cat’s daily energy intake/output. By your practicing HCKE, he should be more relaxed when he is finally on your lap. If the Energetic Balloon has been active all day (meaning in a state of inflation-deflation that you or the environment controls), then the stimulation-o-meter will average about a four out of ten. It stands to reason that getting him to be at a six instead of a nine on that meter during a petting session will save you an unpleasant encounter. Not to take the cat’s side (well, actually, yeah, that’s what I’m doing), the popping of the balloon is on you. Energy buildup–related outbursts are nothing you can really justify being mad about because you can learn to anticipate and prevent them.

Cat Nerd Corner

Why Do Cats Overstimulate?

One theme that we’ve discussed at length is how nature has not missed a trick when it comes to the gifts of survival bestowed upon the Raw Cat. One such feature is the incredibly sensitive touch receptors all over the cat’s body. These receptors detect direct pressure, air movement, temperature, and pain, and they transmit information about the environment to the brain.

There are two key types of touch receptors: Rapidly Adapting (RA) and Slowly Adapting (SA). RA receptors respond to displacement of skin and hair in the moment it happens (and also register the immediate pleasure of touch), but SA receptors continue to fire as long as they are being stimulated, are particularly sensitive to petting, and are mostly responsible for that “I’ve had enough!” reaction. Some SA units are more common on the lower part of the body, where most cats are particularly sensitive to petting.

As predator and prey, the Raw Cat needs to be sensitive. But for his alter ego, the housecat, that survival tool can become a nuisance. We ask cats to handle a lot of touch because we enjoy petting them. Does this mean that your cat shouldn’t ever be petted? Of course not! Armed with this info about how and why cats respond to touch, you should realize that more times than not, that “Don’t touch me!” vibe is a product of physiology, not a choice—which is to say, see it as an “aha!” moment and not a “my cat hates me” moment!

WORDS MATTER

Thus far, we’ve talked a lot about body language, and the particulars of how you might greet or interact with your cat physically. Now, let’s turn our attention to what’s going on between the lines and beyond the physical realm. What are you saying about your cat, both in front of him and otherwise? What words do you use to describe him and his actions?

The words we use are labels that shape how we see the world. They can also be like loaded weapons. When we use words like “attack,” “aggression,” “random,” “mean,” and “vicious,” we’re assigning intention and/or deeper meaning, inaccurate or exaggerated as it may be, to a behavior or action.

Speaking from my experience, specifically with “problem” cats in their homes, I’d say close to 90 percent of the time I’m at least partially dealing with a problem of perception, and the language used around that perception: “My cat is attacking me viciously” or “randomly.” I’m not saying that the description isn’t sometimes accurate, but by and large, it’s just chatter. What may seem to my clients to be just words are, to me, poisoning the well of their relationship with their cat as well as being poison to the cat. These kinds of words suggest that your cat is a stranger to you, creating a wall between you. But I’ve heard them used over and over again for minor offenses like ankle nipping, even in cases where skin isn’t broken . . . and even when no direct contact has been made, for that matter!

But the poison doesn’t end there. When you nonchalantly say things like “he hates me” or “he’s the devil incarnate,” it paints your cat in a way that can’t be unpainted. When you name your cat “Devil Kitty,” “Bastard Cat,” or “Satan,” please, do us all a favor—especially your cat—and change his name to something more dignified . . . or at least a name you would bestow upon a human. Whatever your justification might be, it’s not a valid reason for such a negative label. It’s an unnecessary form of devaluing him that will conspire, on one level or another, to weaken your relationship.

Remember . . . if you say he viciously attacks, then that’s what he does. If you say he’s a bastard, that’s what he is. Labels can hurt, and tone can crush. Cats may not understand English, but they certainly understand tone. The words we use reflect and influence the way we feel about something, but they also convey feeling and nuance—often hurtful—to our loved ones, even when we are not aware of it. This applies ten times as much to your cat. So, if you want to keep your home environment Mojo-fied at all times, you must remain mindful of the words you use around your cat—both spoken and unspoken.

The Kitty Curse Jar Concept

If you’ve gotten in the habit of directing ugly language at your cat, here’s a solution: establish a designated “kitty curse jar.” Then, every time you or someone else calls your cat something like “evil,” “devil,” or “bastard”—put a dollar in it. Do it for a few weeks, and you’ll quickly become aware of how you talk about your cat and see how it can all add up.

Cat Daddy Tip: Oh, and what do you do with the money? Buy your cat a new toy, of course!

PROJECTION

Say you’re having a rough day: You wake up and immediately get into a fight with your significant other; you get a speeding ticket on your way to work; your boss yells at you; then you drop your lunch in your lap. Finally, you get home, exhausted, humiliated, and with salad-dressing pants—and the first thing you see is your cat sitting there, just staring at you. All of a sudden, that frantic inner dialogue kicks in and you’re like: “What? What did I do? What is wrong with you? I put a roof over your head and cuddle you and this is what I get in return? Well, screw you.”

The problem is, you are attempting to make an objective judgment call about what your cat is thinking from an extremely nonobjective place. We call this Projection. In psychology, the term is used to describe the tendency to take our own feelings, insecurities, impulses, or anger and ascribe them to others. In the above story, you were projecting your own negative feelings onto your cat, who you think suddenly hates you.

Cats, in particular, are ripe for human projection, because people often find them “hard to read.” For this reason, they become a blank canvas for us to scribble our manic ramblings on . . . untrue as they may be. That feline tabula rasa becomes a litany of revenge-seeking, masterminding plots on all imagined human wrongdoings. And projection doesn’t even have to come from a place of anger or frustration. Sometimes we think that because we want something—like privacy when we’re going to the bathroom—that our cats must want it, too. Again, not true.

As a result of projection, you can circle down this drain fast and often, and it is purely a result of not understanding cat life, body language, or Mojo. If you keep going down that drain, however, you will continue to unnecessarily degrade your relationship with your cat. Let’s not go there.

AS WE APPROACH the end of this section, I’m hopeful that the Cat Mojo Toolbox system has addressed almost any question or challenge you might have imagined—from the ground up. Moving forward, you’ll need a system in place to maintain the Mojo, so that you can resolve any issues either before they happen or just after they do. This leads us to . . .

CAT DETECTIVISM

Part of the reason I’ve been successful at walking into someone’s home and solving cat problems for them is because I don’t live there. I’m like a detective; I come in, observant and impartial, and I assess a problem. I’m not entwined in the story line, or any drama, projections, or heavy emotions thereof.

Example: Your cat has been peeing in your new boyfriend’s gym bag every night he stays over. You presume your cat is saying “I. Hate. Him.” But to me, pee anywhere is your cat saying “I’m anxious about my territory.” As impossible as it may seem in the moment, there’s no need to take it personally or create a big scene around it. That’s called living in the story. Instead, we investigate the particulars of the how, why, where, and when, and try to resolve the issue. As Joe Friday in Dragnet would always say, “Just the facts, ma’am.” I call this Cat Detectivism.

The art of detached observation will get you through a lifetime of living with your cat successfully. As humans, we don’t have a decent frame of reference for what it is like to be a cat. We can’t pretend we do. I’m not saying you have to be completely detached from a being you love and have a relationship with, but, for their sake, you can damn well do your best.

This is the cardinal rule of Cat Detectivism: you take the actual temperature in the room, not the exaggerated version. If you walk into the house and see a spot of pee, I need you to recognize it as urine—nothing more—then clean it up, forgive, and move on. This will enable you to notice, manage, and diagnose any issue much quicker. Just remember to forgive and move on. Take heightened emotions out of the equation. Forgive and move on. It’s a hell of a lot easier to hot-wire a car when it’s not already running. (Not that I would know.)

With the cardinal rule understood, here are a few more guidelines for Cat Detectivism:

- Simply describe or write down what happened in the “just the facts” style that a reporter might: “It was four o’clock in the morning, I woke up, he was sitting on my chest, I did this, he did that. . . .”

- If you are talking about urine issues, your best friend is a UV flashlight, otherwise known as a black light. You’ve probably seen it in detective TV shows like CSI as an invaluable tool to illuminate blood at crime scenes—not only to pinpoint placement, but the actual spatter, the shape of the stain. This tool is just as invaluable when dealing with urine as with blood. Simply wait till sundown when you can darken the space, and go for it. In many cases, sorry to say, you will probably find more stains than you thought existed. For the sake of Detectivism, record that shape. For instance, little drops can signify a urinary tract infection, while marks that start vertically on furniture or the wall and pool down at the floor tell you most likely it is territorial marking (more on this in section 4).

Also, consider the color of the stain under the light. The darker the stain, the fresher it is. As it fades, it signifies that you’ve either attempted to clean it before, or it is just older. Time breaks down the protein strands of the urine, and with that comes a lighter color. Unfortunately, since cat urine is, in part, designed to permanently mark a surface even after it is completely cleaned, there will be a white “stain” under the black light (and only under the black light, not perceptible to the naked eye) since it broke down the color strands of the rug as well.

- When describing the incident, remove any part that has a qualitative element. If you say he “viciously attacked you” when, in reality, he lightly bit or scratched in response to something like overstimulation, well, now we have some shoddy reporting gumming up the works. I’ve even heard the word “attack” ascribed to perceived intent; the guardian felt that an attack was about to happen. This level of interpretation clearly has no part to play in Detectivism. As we covered earlier, cats don’t behave out of spite (or at least not our anthropomorphized definition of it). And as we covered earlier—words matter. Step away from heightened, sensationalized, or conclusive language. Remember, we’re still just gathering facts here.

- Knowing everything you now know about the Raw Cat, prepare a checklist of anything that could be Mojo threatening. The checklist should address these questions: What raised your cat’s anxiety? What is threatening your cat’s Mojo? Was there fighting? Did you run out of her favorite food? Is the carrier out? Your suitcases? Were there visitors, or outside cats?

- Prepare yourself to be patient. Trust the process, because rushing things usually backfires. There are no deadlines or schedules—it just doesn’t work that way. No matter how hard you try to control the clock, cat problems run on cat time, not human time.

Try to be informed by the behaviors you observe. Think in terms of stress and anxiety, and log behaviors, look for patterns, and write down details. Nothing is random and nothing is personal. All problematic behaviors are rooted in fear, anxiety, and pain, or some combination thereof.

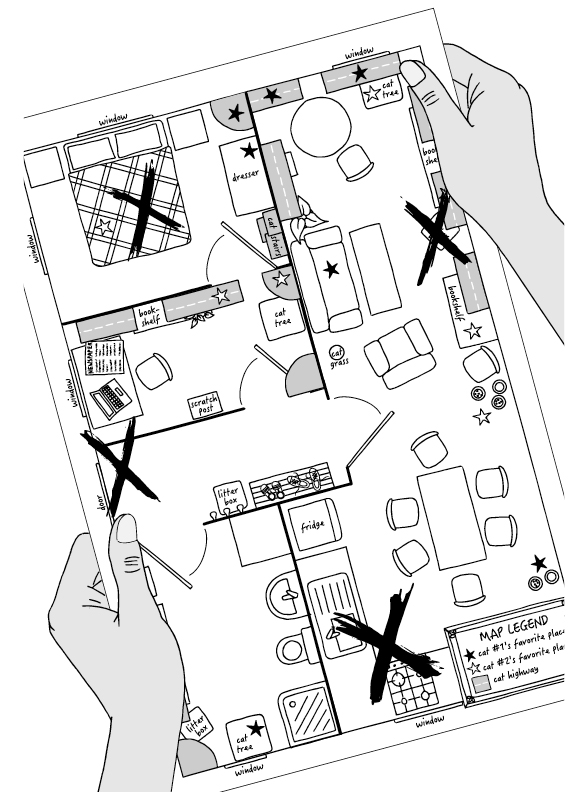

Superdeluxe Cat Detectivism: The Anti–Treasure Map

Cat Detectivism is a great place to use the Mojo Map I introduced in chapter 8. The Mojo Map now becomes the Anti–Treasure Map, where Xs mark the spot where any incidences of unwanted behavior occurred. Whether we are talking about litterbox issues, aggression, or what have you, just slap an “X” on the exact location where it happened. And when I say exact, I mean it: which side of the couch, in front or behind, on the left or right of the front right leg. . . . For a good detective, the devil is in the details.

Also, add a key, of sorts, to your Mojo Map: for each incident, assign the X (or colored star sticker) a number. On the side of the map, record “Just the facts, ma’am.” Time and date, any behaviors you observed before or after, and how close it was to mealtime or any other energy spikes of your home. Using all of the techniques I listed in this section, observe and record. Stick with detached observation, put it down on your map, and build your case. If you have ruled out medical causes for the behavior, I can almost guarantee that if you just gather the Xs for a number of days or weeks, remain detached and just gather information, the Anti–Treasure Map will emerge as Xs mark not just the spots but the patterns. You will see that random acts are anything but.

PREEMPTIVE CAT DETECTIVISM

If I went on TV screaming like the ShamWow guy that there were indelible tip-offs, little shortcuts I could give you in body language—gait, ear position, sleeping or eating patterns—that could predict destructive incidents of peeing or aggression in your cat . . . you might be tempted to grab the bait. After all, most folks see their cat as a collection of symptoms, a four-legged math equation that has a universal solution. Too bad such is not the case. You now know that, through the art of detachment, and the science of observation, you can begin to really understand the unique how, why, where, and when behind what makes your cat do what he sometimes does.

Earlier on, I made it a point that a good detective isn’t entwined in the story line that he enters into. It’s crucial to understand, however, that the story matters only insofar as it furthers your ability to tell the real story. Nothing, in the context of your case, happens in a vacuum; that is to say, use what you know in terms of the story of your cat as only you know it—her physical history, her life before she got to live with you (if you’re fortunate enough to have that information), and the story of traumas she’s endured and how she moved through that trauma. With that information, you can apply it to the present moment in the same way a detective could be interviewing either victim, suspect, or witness, and notice that as the person is telling a story he is tapping his foot and starting to sweat. Your unique perspective on your cat’s life with and before you gives you incredible insights on her present, unusual behavior.

Finally, the next level to aspire to—and much of what we’ll be covering in the final chapters—is the preemptive side of Cat Detectivism. This has to do with what we can do to circumvent or avoid certain anti-Mojo behaviors or actions. The thing is, it’s actually much easier to bring a heightened sense of awareness to the behavior that a cat would exhibit before she acts out. This is an essential mindfulness tool to have on board, because sometimes Cat Detectivism isn’t about saving your carpet from urine—it’s about saving your cat’s life.

A CRY FOR HELP: THE CAT DADDY RED FLAGS

The Raw Cat is always on guard—that’s life smack in the middle of the food chain. There’s always a hunt to be had and always a chance that she may be hunted. For this reason, the very last thing cats can do is show pain. Pain equals vulnerability, and predators can smell what they perceive to be weakness.

Your cat carries that stoic nature with her, along with most of the rest of her ancestor’s survival tactics. That’s why we have to keep an eagle eye out for behavioral changes that may signify physical challenges emerging.

The following list of behavioral red flags is by no means comprehensive, but most have presented themselves to me either in the context of my work or with my own cats. When approaching litterbox issues, for example, I often talk about the concept of cats “raising the yellow flag.” What I’m reminding you of there is that while we are running around, postulating, theorizing, and throwing all kinds of behavioral spaghetti against the wall, seeing what will stick, the cat is actually saying “OUCH!” The upshot is, if you see something out of place, either visually, behaviorally, or just on a gut level, go to the vet.

Living on the fridge or under the bed: This is a sign that something in the environment is threatening. As I mentioned, the Raw Cat, feeling vulnerable because of pain or illness, would also choose to hide or withdraw.

Urinating or defecating outside of the litterbox: There are lots of possible medical reasons, including cystitis, crystals, infection, kidney disease, digestive problems, diabetes, and the list goes on. Two clues to look for that usually signify a physical component: eliminating directly outside the litterbox, sometimes by inches, and very small amounts of pee spread out by a matter of steps.

Chewing on things that aren’t food: See chapter 17 for more on Pica, or the eating of nonfood items.