The Pixie—

Pamela Colman Smith

We are the tyrants of men to come; where we build roads,

they must tread; the traditions we set up, if they are evil, our children

will find it hard to fight against; if for want of vigilance we let beautiful

places be defiled, it is they who will find it a hopeless task to restore them.

–Ford Maddox Ford, “A Future of London” (1909)

London, 1909

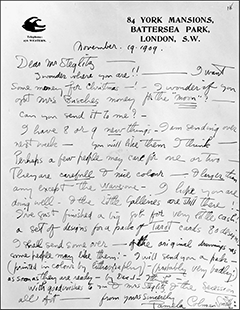

It was a cool, changeable, and generally dull year for weather in London; by November, the residents of York Mansions, overlooking Battersea Park, would have had to be wearing scarves and hats against the cold, despite the sun. At least as is said in England, “It was dry.” One particular resident would have been pleased with this, we think—a certain Pamela Colman Smith (1878–1951), artist and stage designer, was on her way on Friday, the nineteenth of that month to post a letter.

Leaving her small apartment lit by gas lamp (electricity would only be installed a year or so later), Pamela would have a wonderful view of the now winter-bare trees of Battersea Park, the promenade by the Lady’s Pool and Boating Lake, with the river Thames winding just beyond the park itself. Her letter was going to be sent to her art agent in New York, Alfred Stieglitz. It had one important line for the story you are about to discover in this book:

“I’ve just finished a big job for very little cash!”

That job was eighty designs for a tarot deck—a tarot deck that became the best-selling deck of the following century and set the tradition for most decks that followed in its wake.9 In this book, you will learn the secrets of this deck, and we will reveal the magic that Pamela Colman Smith and Arthur Edward Waite evoked into these images.

Before we begin to look at the deck and reveal the secrets scattered throughout it card-by-card, we will take a new look at the life of Pamela Colman Smith and Arthur Edward Waite, who together created this legacy in just less than a year over 1909.

We will see how Pamela’s visits to her friends Ellen Terry, a famous stage actress, and Edith Craig, Terry’s daughter, set the scene for the images of the cards and express their secret meaning.

The Pixie

The year 1909 was one of endings and new beginnings. The Edwardian era would officially come to an end with the death of King Edward VII the following year; society, class, and equality were slowly shifting, and on some levels life appeared to be almost cosmopolitan. The world still unknowingly awaited the two great wars that would so swiftly follow. On the surface, the old geographical and social barriers were being assailed, some conquered for the first time. The world was cracking open. However, the struggle continued for women; the suffragette movement would become increasingly active over the following few years.

It was the year that Louis Bleriot made aviation history with the first record-breaking channel flight from France to England. Later, the monoplane, accompanied by Bleriot, was exhibited at the newly opened department store in Oxford Street, London called Selfridges, owned by American entrepreneur Harry Gordon Selfridge. More than twelve thousand people flocked to see the spectacle.

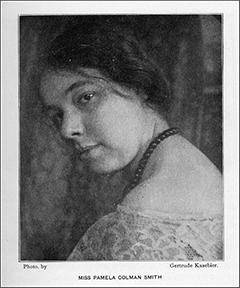

Known as Pixie, the nickname given to her by the famous stage actress Ellen Terry in 1899, Pamela was living at 84 York Mansions on the edge of Battersea Park. She was desperate for money—a situation that would be common in her life. A self-styled bohemian artist, fey and diminutive, she had spent the last several months working on a deck of tarot cards. However, this was not really what she wanted to tell her agent in the letter she sent that November day—she was mainly asking about a payment she had not received for an art piece for a Mrs. Busches called Moon. It was that time of year; she wrote simply, “I want some money for Christmas.”

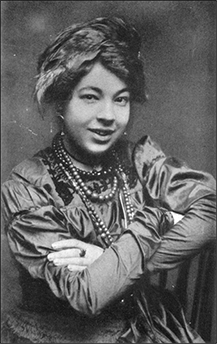

6. Pamela Colman Smith in the Critic, 1899. (Photograp courtesy of Koretaka Eguchi, private collection.)

Pamela had always struggled to make ends meet; her early letters mention her working on commissions such as hand-painted boxes (at least one example survives in Smallhythe Place, Ellen Terry’s cottage) and lamp shades. Whilst not being regarded by biographers as particularly proactive when it came to finances, she did briefly open a “prints and drawings” store in London. It is likely this did not meet with success. In the meantime, she was performing a little in crowd scenes in the theatre through her association with Ellen Terry and Henry Irving.

7. Pamela Colman Smith in The Craftsman, 1912. (Illustration courtesy of authors, private collection.)

It was actually Edith (Edy) Craig, Terry’s daughter, with whom Pamela had a strong relationship. She drew particularly playful sketches of the two of them. The photograph of Pamela at Smallhythe shows her in the company of a group of women—who would dress in men’s clothing and smoke cigarettes—and it is Edy to whom Pamela is turning to smile.

Pamela’s art was influenced by a number of other prominent artists and illustrators, though it was her earlier life she drew on when having to create so many illustrations for the tarot in such a short period of time. In contemporary times, it is often graphic novel (comic book) illustrators who create tarot decks, as they have the speed and style to produce story-board images in a reasonable time. Asking a classic oil painter to produce seventy-eight large paintings takes some time!

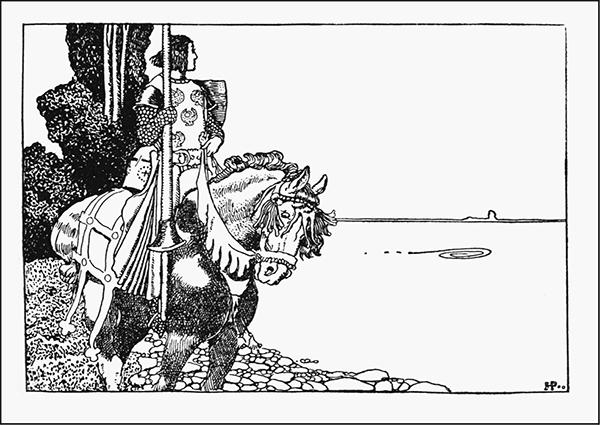

8. Sir Pellias, the Gentle Knight by Howard Pyle, 1903. (Illustration courtesy of authors, private collection.)

So Pamela drew upon her early inspirations, one of whom was Howard Pyle (1853–1911) a prolific illustrator who started a class at the Drexel Institute of Philadelphia in 1894. Pamela applied to the class in 1898, aged twenty, and met Pyle, who described her work as “very ingenious and interesting” but she did not get a place. In fact, it was Pyle who suggested she would be far better travelling to England with Terry. We can perhaps see the influence of Pyle’s illustrations for the legends of King Arthur, Robin Hood, and fairytales—even pirate ships out at sea—in the Waite-Smith tarot.

Pamela’s Life

Corinne Pamela Colman Smith—or Pamela Colman Smith as she is more commonly known—was born to American parents, Charles Edward Smith and Corinne Colman Smith at 27 Belgrave Road, Pimlico, London, on February 16, 1878. Queen Victoria was on the throne and Benjamin Disraeli was Prime Minister. Pamela spent her first ten years living in England; when she was three years old, her parents moved to the north of England in 1881. The census tracks her living in Didsbury, Manchester, on the city’s outskirts.

This industrial city was a place of expansion and a hotbed of women’s emancipation. Prime Minster Disraeli noted that “what Manchester does today, the rest of the world follows.” Considering Pamela’s worldwide lasting legacy of her tarot art, it is fitting that she spent her formative years in this part of the world. It could even be argued that she was a “Lancashire lass” in addition to her other guises and personas.

There is often talk of what Pamela’s speaking voice might have sounded like and whether she had a pronounced accent. It would most likely be that she was taught to speak properly, as she was living in the time of “the Queen’s English.” However, those formative years in Northern England, where the local accent would have been pure Lancashire, would no doubt have influenced her way of speaking, even where that was inherited from her parents. Her natural ability to mimic would have served her well even as a child, and she would likely have been able to switch her accent to suit the occasion and her whereabouts.

Unfortunately we do not know very much at this time about Pamela’s formal education, whether she was taught by a tutor at home, or if she attended a local or boarding school. It must have been tricky for the Smith family living in England at this time; it was Victorian and still stuffy and repressed, partial to social discrimination on many levels. To be Americans and therefore outsiders in England—and particularly Lancashire in the 1880s—would have raised a few eyebrows.

This attitude is evident in the letters of J. B. Yeats (the father of William Butler Yeats and his brother Jack) where he remarks about Pamela and her father, made much later than when Pamela was growing up:

Pamela Smith and father are the funniest-looking people, the most primitive Americans possible, but I like them much.

Here is how Arthur Ransome described his first encounter with Pamela:

The door was flung open, and we saw a little round woman, scarcely more than a girl, standing in the threshold. She looked like she had been the same age all her life, and would be so to the end. She was dressed in an orange-coloured coat that hung loose over a green skirt, with black tassels sewn all over the orange silk, like the frills on a red Indian’s trousers. She welcomed us with a little shriek. It was the oddest, most uncanny little shriek, half laugh, half exclamation. It made me very shy. It was obviously an affectation, and yet seemed just the right manner of welcome from the strange little creature, “god-daughter of a witch and sister to a fairy,” who uttered it. She was very dark, and not thin, and when she smiled, with a smile that was peculiarly infectious, her twinkling gypsy eyes seemed to vanish altogether. Just now at the door they were the eyes of a joyous, excited child meeting the guests of a birthday party.10

Pamela perhaps knew what it was like to feel lonely and be an outsider, that experience of not quite belonging. An only child herself, Pamela would never marry and have children of her own. Her relationship with her father seemed rather restrained and not very emotional, heavy on convention and less on intimacy—not that this would be anything too unusual for the time. The Yeats’s letters suggest this, with a comment relating how her father spoke to her:

“Miss Smith” her father always said even when addressing her.

Pamela and her partner in deck creation, Arthur Edward Waite, had quite a lot in common, from family misfortune to them both converting to Catholicism. Early in life, Waite and Smith would experience the loss of parents; Pamela’s mother died in Jamaica in 1896 when Pamela was only eighteen years old. This was followed three years later, on December 1, 1899, with the sudden death of her father in New York (New York Times obit). This shared experience did not stop there; Waite and Smith both had family roots in America, as Waite was born in America to an American father and an English mother, brought up in England from an early age and residing in England until his death. He very much styled himself an English gentleman.

The comparison with Pamela ends there, however. Pamela’s parents returned to America and divided their time there with long trips to Kingston, Jamaica. In 1888, when she was eleven years old, Pamela and her parents set sail to New York from Liverpool. They arrived on December 17, no doubt in time for the Christmas holidays with their extended family. The lifestyle Pamela lived, travelling and experiencing different cultures, influenced her; she was bohemian in nature, almost butterfly-like, not one to be pinned to the mundane. It was as if she was more at home with her imagination than any land physical.

After this Pamela would spend her time between New York and Kingston to fit in with her father’s work.

There is much speculation in regards to Pamela’s rather exotic looks; we see from photographs that her looks could give rise to any number of interpretations. Yeats wrote in a letter that he thought she “looks exactly like a Japanese.” There is speculation over this even today, and it is hard to completely disregard this when you look at a photograph of her. There are many assertions on the Internet; some say Pamela’s mother was Jamaican or that it was possible Pamela was not the birthchild of her parents. We have documents showing that Pamela’s legal mother was not Jamaican, but American. Pamela’s birth certificate as a legal document places her firmly as the biological child of the Smiths—and nothing other than DNA testing could prove otherwise. (1878, Qrt M, Vol: 1a, 432). Anything other than this is speculation, and speculation it will always be.

The young Colman Smith’s first arrival in the West Indies must have been quite a contrast to the environment she was used to in England. However exciting, it would have been quite an adjustment, just the weather alone!

On October 4, 1893, she arrived in New York on the SS Alene from Kingston. Then aged fifteen years, Pamela travelled with her mother Corinne Smith, aged forty-five years. One thing that becomes apparent from primary sources such as the census and the passenger lists is that Mrs. Smith was fluid with her age, not just by the odd year but by up to twelve years. In this, she was in good company with the likes of Nellie Ternan (1839–1914), the mistress of Charles Dickens; Ternan erased fourteen years of her life when she married for the first time at her “actual” age of thirty-seven. She told her husband she was a mere twenty-three years of age! It was a time when it was simpler to conceal and fabricate information and even reinvent yourself. It does make one a little curious about whether Corinne Smith was attempting to conceal a secret other than her age.

Once established in New York, on October 23, 1893, Pamela enrolled at the Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, New York, whose motto is “Be true to your work, and your work will be true to you.” Here she would be schooled in techniques that harnessed her unique style that would birth the Waite-Smith tarot seventeen years later. A tutor who was to influence her abilities was Arthur Wesley Dow. She left Pratt in June 1897.

It was perhaps in 1901 when she met up with Ellen Terry and Edy Craig. Pamela forged a special relationship with Edy; they both shared the same sense of fun and a delight in being mischievous. It was in this company that Pamela drew the caricatures of the group and the images of her and Edy as “devils” Pixie and Puck. This self-cartooning of Edy and Pamela is also present in Ellen Peg’s Book of Merry Joys, or the Peggy Picture Book (1900) they created together. Poking fun at the solemnity of Stoker and the autocracy of Irving, Pamela portrayed Stoker as “Bramy Joker” and Edward Gordon Craig as “the Tedpecker.”11

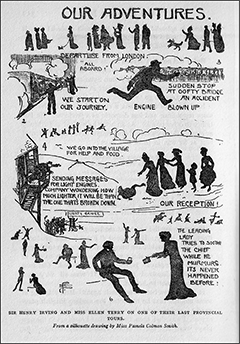

9. Our Adventures, Pamela Colman Smith, 1902. (Illustration courtesy of authors, private collection.)

In 1902, Pamela stayed with the Davis family in Kensington, London. The Davises were cousins by marriage to Ellen Terry and part of the acting fraternity themselves.

On January 28, 1909, Pamela travelled alone to New York aboard the Minnetonka to attend her exhibition. She would return to England on May 24, 1909. It is from this date (we think it unlikely she would have started beforehand) that we can assume she started the tarot work, which was completed by November. Allowing her a few days to get herself unpacked, this means that the deck was created in no more than five and a half months.

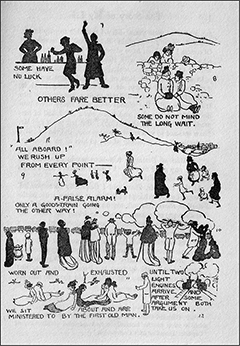

10. Our Adventures, Pamela Colman Smith 1902. (Illustration courtesy of authors, private collection.)

On March 24, 1916, she applied for a US passport. Her occupation is classed as “Artist & Illustrator” and that she had last left the US in April 1912. Her permanent residence was recorded as Carlyle Place, London. Pamela was thirty-eight years old, described as being

5' 4", and having dark brown hair, brown eyes, a broad nose, round face, a medium forehead, and medium complexion. Pamela’s actual passport photograph is reproduced at www.waitesmithtarot.com. Her citizenship is attested by letters from three people, one of whom is Ellen Terry, then residing at 2 Kings Road, London. This latter fact is interesting as it shows that whilst Pamela may have changed her circle of friends by 1913 due to her conversion to Roman Catholicism, she was still in touch with Terry three years later and the relationship was still close enough for her to ask for this favour.

Pamela and Opal Hush

One record we have of Pamela’s favourite drink at the time is given in Ransome’s description of her party. There she served Opal Hush, and we can give a likely recipe for this simple cocktail: about a third of a short glass of red claret topped with lemonade delivered through a siphon. The aim is to have a nice “amethystine” rose foam on the surface of the drink. If you wish, add ice and a slice of lime for garnish, and drink through a straw.

The drink was a good way to make cheap claret last longer, and was possibly named by W. B. Yeats or “AE,” who was George William Russell (1867–1935). He was supposed to go by the name “AEON,” but a publisher missed the last two letters, so he became AE.

Pamela’s Name

“Pixie” and “Puck” were the nicknames of Pamela and Edy Craig, likely given by Ellen Terry. A telegraph from her to Mary Fanton Roberts (1864–1956) in 1907 is simply signed off as Pamela Smith. Roberts was a leading light in theatrical circles in New York and editor of The Craftsman, and Pamela arranged to meet her in January 1907.12

Pamela’s Magical Motto

Pamela’s motto in the Golden Dawn was Quod Tibi Id Allium (Q. T. I. A.), which translates as “Whatever You Would Have Done to Thee,” although Gilbert suggests it should read Quod Tibi id aliis.13 This motto is a version of Matthew 7:12 and Luke 6:31, the so-called Golden Rule of doing unto others as you would have done unto yourself.

Pamela’s Art and Influences

The first female artist to be given a gallery exhibition by Alfred Stieglitz, Pamela’s work there has since been described by Kathleen Pyne, Professor of the History of Art at the University of Notre Dame, as the art of “an androgynous sorceress, a prophetess who seeks and finds the cosmic, heroic voice in nature.”14 Pyne compares one self-portrait, Beethoven Sonata No. 11—Self Portrait (1907), to the art of tarot in which a “medium seeks and finds a vision of the future” and ultimately, as evidenced by Sketch for Glass (1908), “is reborn into a state of spiritual enlightenment.”15

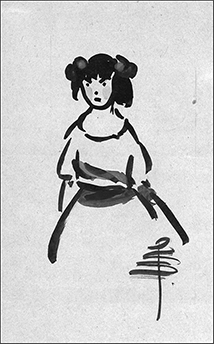

Pyne notes that Pamela presented herself to Stieglitz as a visionary, claiming—as we see elsewhere—that her art was drawn from the “subconscious energies” of her mind, liberated by music. Pyne also lists Pamela’s inspirations as Kate Greenaway, Walter Crane, William Blake, and Japanese printmakers such as Hokusai.16 Pyne suggests that the childlike nature of Pamela’s presentation was deliberately cultivated as it appealed to those seeking an artist who was tapping into the depths of the psyche.

Pamela was able to rapidly create character and personality from just a few brush-strokes, indeed, similar to certain styles of Japanese art. It is almost zenlike in its simplicity.

11. Portrait of a Young Girl, Pamela Colman Smith. (Illustration courtesy of authors, original painting in private collection.)

12. W. B. Yeats by Pamela Colman Smith, 1901. (Illustration courtesy of authors, private collection.)

She was also able to paint quickly. A confirmation of Pamela’s rate of production is given through a letter written by her to Stieglitz in late 1907, where she relates that in one recent week alone, she had completed ninety-four drawings, “almost all of them usable ones.”17 It was just two years later that her speed of creation would be put to use by Waite in the rapid production of their tarot deck.

That Pamela was not “school-taught” is evident in her work, her advice to other artists, and the reviews of her work. In a 1903 review of Pamela’s new venture, The Green Sheaf, her work was characterised as having benefitted from her move to London. Her work was characterised as possessing “the freshness, the spontaneity, the naïve charm that owed everything to nature and little or nothing to the schools.”

In this environment that “better conserves her inherent tendencies” she had started The Broad Sheet with Jack B. Yeats, and had in 1903 released the first of her Green Sheaf publications. She wrote this about the periodical:

My Sheaf is small … but it is green. I will gather into my Sheaf all the young, fresh things I can—pictures, verses, ballads of love and war; tales of pirates and the sea.

You will find the ballads of the old world in my Sheaf. Are they not green forever.

Ripe ears are good for bread, but green ears are good for pleasure.

I hope you will have my Sheaf in your house and like it.

It will stay fresh and green then.

Whilst noting that the contributors to the Sheaf are those associated with the new Irish literary movement—and more theatrical contacts such as Christopher St. John and others—the reviewer also points out that “the largest contributor is Miss Smith herself.”

When she resigned from working on The Broad Sheet in 1903, Jack Yates noted with some regret that she always “has so many ‘irons’ in the fire that she can never do the colouring with any comfort to herself.”

Pamela was proposed as a member of the RSA (Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce) by Committee and given that fellowship on October 13, 1941. Her occupation was listed as artist, illustrator, and interestingly, teller of folk stories from Jamaica.18 This moment of recognition came just ten years prior to her death in 1951.

The Secret of the Flower Book

In Rottingdean, a small village just a little farther down the coast from Winchelsea, between 1882–1898, the artist Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898) created a series of thirty-eight small circular paintings as a leisurely pursuit from his other work.19 Most of the images were created in Rottingdean, and were inspired by the same landscape of East Sussex as the Waite-Smith tarot.

The book contained paintings inspired by the names of flowers and was circulated by his wife as The Flower Book, of which just three hundred copies were made in 1905. In 1909, the year in which the Waite-Smith tarot was created, the book was purchased and deposited in the British Museum where both Waite and Pamela might have seen it, had they not done so before. Certainly Pamela would have likely been aware of the book, as Burne-Jones was a major influence on her work.

As we will see in our exploration of individual cards, The Flower Book contains several images that likely inspired Pamela’s art. Burne-Jones intended not to illustrate the flowers but “wring their secret from them.” He illustrated the names with mythic, biblical, and Arthurian images, many of which bear an uncanny resonance to Pamela’s work on the tarot.

To find one picture out there in the art world that bears a “similarity” to Pamela’s work is not difficult, as all art ultimately deals with the same themes. However, when we discover a whole sequence of images by an artist known to Pamela and which were in circulation prior to her own work, it is difficult not to see that these would have inspired her project.

14. False Mercury by Edward Burne-Jones. (Courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum, used under license.)

The particular cards we will look at in this light are the 2 of Pentacles and the 2 and 3 of Wands, although we offer here a list of other possible correspondences for those readers who may wish to allocate these particular flowers and titles to the cards in the style of Burne-Jones:

Majors

- Lovers: Adder’s Tongue

- Hermit: Witch’s Tree

- Temperance: Flower of God, also Ladder of Heaven

- Devil: Black Archangel

- Star: Star of Bethlehem

- Tower: Arbor Tristis

- Last Judgement: Morning Glories

- World: Rose of Heaven, also Marvel of the World

15. Comes He Not by Edward Burne-Jones. (Courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum, used under license.)

Minors

- Ace of Cups: Golden Cup

- Ace of Pentacles: Golden Gate

- Ace of Wands: Key of Spring

- 2 of Pentacles: False Mercury

- 2 of Wands/3 of Wands: Comes He Not

- 6 of Swords: Flame Heath

- 9 of Pentacles: Love in a Tangle

- 9 of Swords: Wake, Dearest

- 9 of Wands: Helen’s Tears

Court Cards

- Knight of Pentacles: Saturn’s Loathing

- Knight of Swords: Honour’s Prize

The Secret of the Theatre

Pamela was a child of the theatre. She went as far to say that “the stage has taught me almost all I know of clothes, of action and of pictorial gestures.”20 She suggested that the stage was a great school for the illustrator, as well as the observations of everyday life. As we will see later, in our chapter on “Pamela’s Music,” she was also aware that she had the ability to see music as images (synesthesia); she wrote in 1908 that “sound and form are more closely connected than we know.”21

Pamela had both her own personal experience and knowledge of the theatre and also through Irving, Gillette, Terry, and the stage design ethos of Edward Gordon Craig, Ellen Terry’s illegitimate son. It was Craig who had truly grown up in the theatre; he was an influential and innovative stage designer, writing On the Art of the Theatre in 1904.

If we look at Pamela’s advice for perceiving art taken from her own experience and look through the lens of neuro-linguistic programming (NLP), we can perhaps model her methodology and use it. In fact, it turns out that Pamela actually describes a technique already known in NLP called the “Swish Pattern.” It works with the way we tend to put things into the “corners” of our minds.

To incorporate this method in our card reading based on modelling Pamela’s own description of how she created her art, we would take the following steps.

Pamela’s Reading Method

Select a question. Keep it short and succinct. We will use a one-card method for this, although it is possible with practice to use several cards. Shuffle your deck, considering the question, and turn it face down—you are going to read the card on the top of the face-down deck, but not yet.

Now imagine the question as a piece of text or writing inside your mind on a large mental screen. You may need to close your eyes. Choose a good font and colour for the text. Read it several times inside your mind. If you are not a naturally “visual” person, simply imagine that you have these words, or hear them—you can even feel them if you wish, so long as you have a strong representation inside your mind.

Close your eyes, if you have not already done so, and take a deep breath in. As you do so, “squish” your mental screen text into the bottom-left corner of your mind. It should be a small box, like a flashing cursor, with no text viewable in it.

Now open your eyes and turn over a card.

As you see the card, imagine the text inside your mind springing back up from its box to its full size, as Pamela says, “Call it up … and review your work in front of it.”22 See the image in front of the text, as if the text is a watermark or transparency behind the card.

Allow any feelings to arise in answer to the question. It may even be that you do not get anything consciously, but over time answers arise, solutions present themselves, or dreams provide insight. This is often an entirely unconscious process, tapping into the deep well from which Pamela drew her art.

Other considerations you may adopt in your reading of the Waite-Smith deck based on what Pamela felt was important to her art are:

- Body Posture: Pamela says “First watch the simple forms of joy, of fear, of sorrow; look at the position taken by the whole body, then the face—that can come afterward.”

- Clothing: how it is worn, not the costume itself. That is, “Look at the clothes, hat, cloak, armor, belt, sword, dagger, rings, boots, jewels. Watch how the cloak swings when the person walks, how the hands are used. See if you can judge if the clothes are correct, or if they are worn correctly; for they are often ruined by the way they are put on. An actor should be able to show the period and manner of the time in the way he puts on his clothes, as well as the way he uses his hands, head, legs.” 23

- See what is exaggerated: Pamela suggested that whilst the stage may be “false and unreal,” so too is illustration. In what she chose to exaggerate in an image, we can sense what she wanted us to feel. And she said, “Above all, feel everything! And make other people when they look at your drawing feel it too!” 24

When we apply these simple observations to a card such as the 9 of Cups, we can see that the actor has adopted a very wide and exaggerated sitting stance. If you take this stance, you will feel instantly that it is a front—a pretence. Your hands rest loosely on folded arms that are actually kept quite wide, and your feet point widely outwards, the right slightly ahead of the left. You may even feel as if you are about to break out into a Ukrainian hopak (sometimes called a Cossack dance).

This character is clearly “puffed out” in his own self-importance. Yet he does it to protect something; we feel that too from his body language. This, along with our later Falstaff connection, deepens the card dramatically and provides profound meaning in a reading.

All the World’s a Stage

Pamela’s connection between the theatrical tradition and her art has been emulated with decks that specifically draw upon theatre as well as other influences on Pamela, such as the Blake Tarot created by Ed Buryn.25 There are at least four Shakespearian-themed tarot decks in publication:

- I Tarocchi di Giulietta e Romeo: by Luigi Scapini, also known as

the Shakespeare Tarot and the Romeo and Juliet Tarot, (U.S. Games

Systems, 1996). - The Shakespearian Tarot: conceived by Dolores Ashcroft-Nowicki,

artist Paul Hardy (U.S. Games Systems, 1993). - The Shakespeare Oracle: conceived by A. Bronwyn Llewellyn with artwork by Cynthia von Buhler (Fairwinds Press, 2003).

- Russian Shakespeare Tarot: edited by Vera Skljarova, in 2003.26

In several of these decks we are given correspondences between the cards and Shakespearian characters and quotes. In the Shakespeare Oracle are given:

|

Sceptres (Wands) |

Chalices |

Quills (Swords) |

Coins |

|

|

King |

Philip the Bastard |

Antony |

Richard III and Henry Bolingbroke |

Shylock |

|

Queen |

Katharine of Aragon |

Hermione |

Beatrice |

Helena |

|

Lord (Knight) |

Richard Plantagenet |

Valentine |

Armado |

Falstaff |

|

Lady (Page) |

Volumnia |

Rosalind |

Viola |

Mistress Page |

We provide variant choices for the court cards in a separate chapter, as understanding the dramatic nature of these characters can deepen their relevance to our everyday dramas.

Pamela’s Working Life

As a self-styled bohemian artist, Pamela’s working life was without plan or structure. She also appears to have paid little attention to her finances. Her letters constantly refer to lack of funds and the pittance she has earnt from her publishers or colleagues. She seemed to always have many low-income projects on the go as we might suspect was necessary; advertisements for her work in the back of The Green Sheaf magazine included lace designs, a school of hand colouring, portraiture, and a storytelling service.

Her humour, lack of reverence, and self-styled childlike nature may have also stopped her progressing in her artistic career long-term. She described W. B. Yeats not in terms of the awe that some held him in, but as a “rummy critter.” Her description of a reading of “The Shadowy Waters” by Yeats and Florence Farr testifies to her childlike perspective: because of the curiously ill-chosen voices for the sailors’ chorus, she said she had to “laugh in [her] hankie” most of the time. One suspects she had deliberately arrested her development given her language, such as “it was fun and we all liked it very much!” and talking about “how very much they liked his bloomin poetry.” 27

The Pall Mall Gazette of November 28, 1899 reviewed children’s books for Christmas, and it carried a brief review of In Chimney Corners, a book for “older children.” Whilst admiring Mr. McManus’s storytelling, the reviewer remarks that “one doubts that the grotesques of Miss Pamela Colman Smith will add to the book’s attractiveness, though that she has some of the qualities for her task is proved by the fantasy of the illustration which faces the title page.” 28

Pamela also provided posters, such as noted in the Industrial and Fine Art Exhibition held at Grantham, reported in the Grantham Journal of January 25, 1902 (2). Her poster announcing a dramatic performance onboard the SS Menominee, on the return voyage of the Lyceum tour, was particularly admired as it carried the signatures of both Irving and Terry in addition to a portrait of Irving.

We also know that Pamela produced a poster for the Polish Victims Relief Fund in 1915.29 If she was indeed a friend of Laurence Alma-Tadema (1865–1940), the Secretary of the Fund, then perhaps they shared the same feelings as evidenced in this poem by Alma-Tadema:

If no one ever marries me,—

And I don’t see why they should,

For nurse says I’m not pretty,

And I’m seldom very good—

If no one ever marries me

I shan’t mind very much;

I shall buy a squirrel in a cage,

And a little rabbit-hutch:

I shall have a cottage near a wood,

And a pony all my own,

And a little lamb quite clean and tame,

That I can take to town:

And when I’m getting really old,—

At twenty-eight or nine—

I shall buy a little orphan-girl

And bring her up as mine.

Alma-Tadema lectured on the secret of happiness, saying that happiness is attained by “working hard, controlling one’s self, and developing one’s faculties to the limit.”30 We wonder if Pamela shared this gauge of happiness.

Like Pamela, she also never married and, interestingly, lived in Wittersham, in a large cottage called Fair Haven she renamed “The Hall of Happy Hours,” where she performed music and plays. The interesting thing is that Wittersham is less than three miles south of Smallhythe Place.

Pamela was involved in charity work and supporting women’s causes several times. The Sheffield Daily Telegraph reported by wire from London on December 9, 1903 that there would be a Christmas “Hans Andersen” Bazaar, opened by the Princess Alexis Dolgorouki in aid of the Girls’ Realm Guild of Service (6). At this bazaar would be Miss Pamela Colman Smith who “has already won a reputation for the telling of quaint West Indian stories of the ‘Brer Rabbit’ order,” and was sure to “delight the children of the audience.”

The Grantham Journal of September 24, 1904, carried a listing of “A Quaint Story-Teller” (Miss Pamela Colman Smith) by J. A. Middleton in the Lady’s Home Magazine (6d).31Pamela was still earning a living of sorts from storytelling in 1907, when she is reported by the Nelson Mail (May 4) as entertaining Mark Twain—who apparently laughed like a child all the way through her recital.

In 1907, Pamela wrote to Stieglitz and told him she had managed to sell all the platinotypes he had sent, for $35, to “Mrs Lance’s Mother.”32 Her business sense and organisation—or lack of both—is clearly evident in this letter, as is—perhaps—her lack of confidence. She asks him to deduct “the part of it which is yours” from the $35. She was also concerned and confused about the literature she had been sent from a Philadelphia exhibition, which might have carried her portfolio; she asked Stieglitz if it had been put on display, and “did people shout with glee? Or were they just scornful?” A side note asked him to send a copy of something she had lost. She continued that she had been doing a “lot of stuff” for the Herald.33 Like her others, this letter seems lively but scattered.

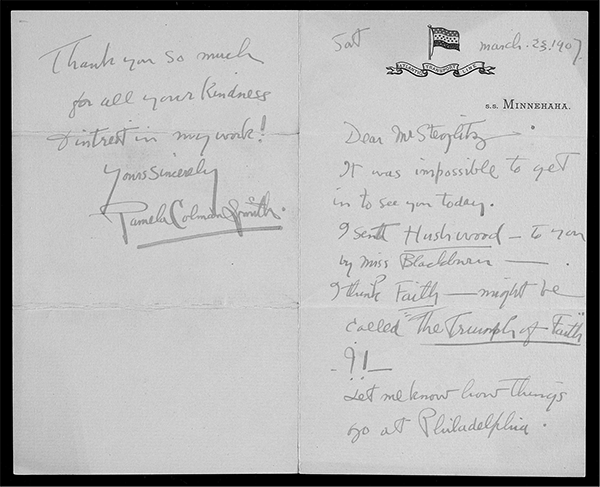

Earlier that year she had written to him from the return trip, on stationary headed by the SS Minnehaha, to thank him for “all your kindness and interest in my work” and to say she had sent him her piece, Hushwood, and that a prior piece, Faith, she would like to be called The Triumph of Faith.

19. A Letter from Pamela to Stieglitz, 1907. (Illustration courtesy of authors, private collection.)

In 1912, the Kent & Sussex Courier of May 31 (7) spoke of the recitals of Miss Jean Sterling Mackinlay, who was assisted by “Miss Pamela Colman Smith, who tells amusing folk stories from Jamaica.” Mackinlay (and likely Pamela in support) was giving recitals at Eastbourne and Madame Pavlova’s special matinees at the Palace Theatre, London, throughout the summer of 1912. She also had an exhibition of her work in New York in the spring of that year, followed by another in Ghent, Belgium, in 1913.

Pamela’s Pennies

We have only one reference known regarding the payment Pamela received for her work, which was in her letter to her art agent and promoter, Stieglitz. She explained she had received “very little cash” for the “big job.” At the time, she completed the job literally a few weeks before the British government enacted the 1909 Trades Board Act, guaranteeing a minimum wage to all workers. Unfortunately, even once this act was in place there was no evidence it applied prior to the outbreak of the first World War some five years later.

Average wage was about three shillings a day, and it appears likely Pamela received even less, for she was just completing the job and still requiring “money for Christmas.” If she worked on the deck during her stay at Ellen Terry’s, earning money through nannying, personal assistance, or paying her keep by work, then it is probable that in today’s money, she would have earned less than seven hundred pounds for the entire project.

William Rider and Sons advertised the deck (without postage included) at five shillings.

Pamela and Sherlock Holmes

On the banks of the river Connecticut, in East Haddam above the ferry, stands a castle. It was completed in 1919 by its designer, William Gillette (1853–1937). Gillette was famous for his portrayal of Sherlock Holmes and one of America’s greatest actors of the time. He was also related through the Hooker family to Pamela’s parents. The connection must have been known at the time, or Pamela came into touch with Gillette through their common theatrical bonds, as in 1900, Pamela created several illustrations for a Gillette souvenir book.

However, there are other interesting overlaps to the story of Sherlock Holmes that intersect with magick; the famous deerstalker hat and pipe were not in Doyle’s original books but added in illustrations by Sidney Paget (1860–1908). These were used by Gillette in his own role, bringing the iconic elements to the character. Paget was a member of the Golden Dawn and friend of Florence Farr, another significant member of the Order. He even performed

in a play of Farr’s, The Beloved of Hathor, as King of Egypt.

Furthermore in these overlapping connections, Doyle (who had himself considered joining the Golden Dawn in 1898) first offered the role of Holmes to Henry Irving but then had passed it on to Gillette because Irving wanted to play both Holmes and his nemesis, Moriarty.

The bow that ties these connections up in a nice present is to be found in Gillette’s Castle; if you visit today, you can see several original portraits by Pamela hanging on the walls, collected by Gillette.

20. Pamela Colman Smith Picture in Gillette Castle. (Courtesy of Gillette Castle State Park, used with permission.)

Far From the Garden of the Happy:

Pamela and the Golden Dawn

It appears that Pamela’s time in the Golden Dawn was somewhat of a cursory affair; she likely joined on November 2, 1901, and by 1904 she was still in the Zelator grade.34 Whilst to date it has been uncertain as to her exact date of initiation, we can now compare, courtesy of the membership roll of the Golden Dawn, the name of the person she may have been initiated with, to the census, where we discover indeed that Ethel P. F. Fryer-Fortesque was living in the same property, 14 Milbourne Grove, London, as Pamela in 1901. So it is very likely they initiated together, Ethel aged thirty-five and Pamela aged twenty-three. In fact, this may be the same “Mrs. Fortesque” with whom Pamela set up a shop selling hand-coloured prints, engravings, drawings, pictures, and books in 1904.35

21. Golden Dawn Membership Roll. (Courtesy of the Library and Museum of Freemasonry, London, used under license.)

Ethel was the daughter of the Davis family, her mother being Ellen Davis, aged seventy-two and a widow at the time. There were five people living in the property and a servant, and this is where Pamela was recorded as boarding, but it also had rooms next door at number 13 where Ransome attended her gatherings.36

The date on the membership roll was recorded against Alexander Davidson-Gordon, a doctor who took the name Lux e Tenebris (“light in darkness”).37 So perhaps the initiation was performed on these three candidates together; it was often that a small group of candidates were initiated at the same time. If it did, it occurred on a rather strange Saturday when the centre of London was enveloped in a “black fog,” which even crept into theatres and music halls, obscuring the stages. One report gave a description of link-boys (bearing lanterns) leading the well-to-do back to their homes, giving a bizarre medievalism to the city. It would be with some irony then that Davidson-Gordon took the motto that night, “light in darkness.”

22. Golden Dawn Membership Roll Close-Up with Pamela’s Name. (Courtesy of the Library and Museum of Freemasonry, London, used under license.)

So Pamela would have experienced the Neophyte ritual, and possibly the Zelator ritual, in which the first symbols of esotericism would have been richly presented.

For one such symbol, she would have entered the Hall bound and blindfolded, a motif which appears in the deck—particularly on the 2 and 8 of Swords. Her initiators would have spoken:

The Three Fold Cord bound around your waist was an image of the three-fold bondage of Mortality, which amongst the Initiated is called earthly or material inclination, that has bound into a narrow place the once far-wandering soul; and the Hood-wink was an image of the Darkness, of Ignorance, of Mortality that has blinded men to the Happiness and Beauty their eyes once looked upon.38

The altar, the black and white pillars, the ever-burning lamps, all of these would have been part of the tapestry being woven in her consciousness as she was initiated.

If she had also been formally initiated as a Zelator, then further mysteries would have been revealed to her. These would have included the mystery of the rainbow: the three paths leading up the Tree of Life, spelling QShTh, Hebrew for “rainbow.” She would have been told:

The Three Portals facing you in the East are the Gates of the Paths leading to the three further Grades, which with the Zelator and the Neophyte forms the first and lowest Order of our Fraternity. Furthermore, they represent the Paths which connect the Tenth Sephirah Malkuth with the other Sephiroth. The letters Tau, Qoph, and Shin make the word Quesheth—a Bow, the reflection of the Rainbow of Promise stretched over the Earth, and which is about the Throne of God.39

That she did not progress beyond this grade even before the various schisms that disrupted and eventually broke apart the Order is perhaps because of her natural inclination towards intuitive art and not intellectual learning.

There were various knowledge lectures bestowed upon the candidate at this point, and we have no evidence that Pamela learnt these materials or progressed to more advanced studies. However, she would have likely remembered the experience and teachings of these ceremonies, which are powerful even for those without her intuitive talent.

Her teaching materials would have included rudimentary descriptions of the Tree of Life (and a diagram), basic teachings of astrological signs and symbols, a little alchemy, and most importantly, in the second Knowledge Lecture of a Zelator, she would have been first introduced to the tarot:

The traditional Tarot consists of a pack of 78 cards made up of Four Suits of 14 cards each, together with 22 Trumps, or Major Arcana, which tell the story of the Soul.

Each suit consists of ten numbered cards, as in the modern playing cards, but there are instead three honours: King or Knight, Queen, Prince or Emperor, Princess or Knave.

The Four Suits are:

- Wands or Sceptres comparable to Diamonds.

- Cups or Chalices comparable to Hearts.

- Swords comparable to Spades.

- Pentacles or Coins comparable to Clubs.40

We can only remark with astonishment that this brief paragraph may have been Pamela’s first and only formal teaching in tarot, and yet some several years later she created—in just five months—what is arguably the world’s most popular and emulated tarot deck.

The initiate of the Zelator grade is given the mystical title of Periclinus de Faustis, which “signifies that on this Earth you are in a wilderness, far from the Garden of the Happy.”41 It is perhaps this garden that Pamela was always attempting to attain.

The Sola Busca Deck

The Sola Busca deck is the earliest complete tarot deck known, and until recently it belonged to the Sola Busca family. It was acquired in 2009 by the Italian Ministry of Heritage and Culture from the heirs of the family and presented to the Pinacoteca di Brera gallery for display and archiving. An exhibition of the deck was held in late 2012, which the present authors attended.

In attending this exhibition, we were again following the footsteps of Arthur and Pamela, who just over a century before had likely attended a display of photographs of the same cards held in the British Museum in 1907. The black and white photographs of the entire deck were displayed in the museum next to twenty-three original engravings that had been acquired by the museum previously in 1845.42

The similarity of several of the images of the Sola Busca deck to Pamela’s execution of the tarot was first noted by Gertrude C. Moakley and documented in Stuart Kaplan’s Encyclopaedia of the Tarot Vol. III (1990).

According to the most recent research, the original cards were painted in Venice in 1491, by Nicola di Maestro Antonio d’Ancona.43 This places the inspirational soul of the Waite-Smith deck firmly in Venice and likewise some of the design elements that were continued through the deck. These are particularly noticeable in certain cards (see below) but also through the alchemical symbolism.

Waite would have been very much aware of the alchemical symbolism of the cards; however, this was obviously not passed on to Pamela, other than as a very general idea (see the 7 of Cups).

Snuffles and Others: The Influence

of Pamela Colman Smith on Contemporary Tarot

That Pamela should include Snuffles the Cat in her depiction of the Queen of Wands (as we’ll see later) sets an important marker for tracing her influence on all following card design. This symbol, a black cat, is one of many that are unique to Pamela’s design and it has been reproduced without question in the majority of all clone decks. The secret of the symbol is simple; Pamela was painting the Queen of Wands and used Edy Craig, a chair in Smallhythe Place, a sunflower from the garden, a pole from the trellis-work they were building, and Snuffles as a model of the nature of the character she was painting.

Her only esoteric source at that time was likely to be Book T, or portions of that Golden Dawn manuscript given or spoken to her by Waite. She would have encountered the Queen of Wands as:

The Queen of the Thrones of Flame. A crowned queen with long red-golden hair, seated upon a Throne, with steady flames beneath. She wears a corselet and buskins of scale mail, which latter her robe discloses. Her arms are almost bare. On cuirass and buskins are leopards’ heads winged. The same symbol surmounteth her crown. At her side is a couchant leopard on which her hands rest. She bears a long Wand with a very heavy conical head. The face is beautiful and resolute.44

In the Golden Dawn version of the card, sketched possibly by Moina Mathers, we see that whilst there is a leopard at her feet, her hands do not rest upon it. It is likely that the text version was written by a non-artist (likely MacGregor Mathers) and there is a composition issue when trying to draw a seated figure, holding a long wand whilst also having both her hands “resting on” an animal that is lying down at one side. There is a feline face on her “cuirass and buskins” and on her crown.45

Pamela took this description (or one similar) and drew Edy Craig as her Queen of Wands, and Snuffles replaced the leopard, which she may have felt was a little out of place in her deck. We see this sketching-out and dilution of the original Golden Dawn correspondences throughout the deck; her usage of the four various creatures issuing from the Cups in the court cards (turtle, serpent, crayfish, and crab) is limited to the Page, for example, which simply shows a fish emerging from the cup.

Once the cat was out of the bag and into the image, so to speak, it has almost become sacred to the deck. Its presence was then reinterpreted by every author, so for example Eden Gray views the cat as “the sinister aspect of Venus,” an unexplained attribution that is unique here but often repeated.46 It has also been connected with superstition, the inner nature of the Queen herself, a guide, guardian, symbol of occultism, and much more. In the Feminist Tarot, the cat is part of the Queen’s identification with “Diana the Huntress, protector of her sisters, avenger of their enemies.”47

That is not to say that the cat symbol cannot be read in whatever context it appears in a question; nor should it stop appearing on every Waite-Smith-type deck in future! Here we are simply tracing the genesis and evolution of a symbol through a tradition-in-development. We are sure Snuffles will continue to be immortalised, and is likely very pleased that he replaced a leopard.

We will now take a look at a couple of cards in a contemporary deck, the wonderfully vibrant and unique Gypsy Palace tarot to see how Pamela’s work has influenced, inspired, and been the starting-block for many modern decks. This analysis could be repeated for many of the thousand or more decks in contemporary circulation.

The Gypsy Palace Tarot

The Gypsy Palace tarot was published in 2013 by Hungarian artist Nora Huszka.48 Whilst this deck draws on traditional roots, we would like to select a few cards to demonstrate the legacy of Pamela’s design and art. This process can be repeated for any deck since 1909, showing the influence (or not) of Pamela’s designs and Waite’s intent on tarot for a century.

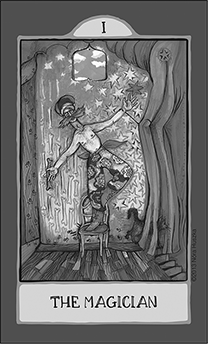

The Magician, for example, mirrors the posture of Pamela’s Magician; his arms stretched out above and below, dividing the card diagonally. Nora says of this image, “His special kind of power is based on connecting the evanescent earth and the eternal sky.”

However, the wand of the Waite-Smith Magician is now a bone and it faces down towards the ground, the opposite to Pamela’s wand held up above. The Magician of the Gypsy Palace is profane, whereas Pamela’s is sacred. This inverted image transforms Pamela’s hermetic Magician into a vibrant shaman, and in both decks they demonstrate the state of being between the worlds.

It is coincidental that the image in Nora’s deck contains a black cat, sneaking away between the veil-like curtains. Perhaps Snuffles is having a laugh with us.

In the 9 of Pentacles the female figure has a bird on her hand, again, straight from Waite-Smith. It has a certain amount of freedom, yet it is beholden to another. Here we see a symbol that has been passed from the Sola Busca deck, through Colman Smith, to contemporary decks.

|

|

|

23 & 24. 9 of Pentacles and the Magician,

Gypsy Palace Tarot, Nora Huszka. (2013, Self-published.)

The Waite-Smith Deck in Contemporary Culture

From the “Hollywood” backdrop of Madonna’s Re-Invention tour (2004), to its appearance alongside a custom deck designed by Fergus Hall in the James Bond film, Live and Let Die (1973), the Waite-Smith tarot is instantly recognisable. The irony of the deck shown in the Bond film is that if you look closely, because the prop is from the production merchandise deck created with the film, the cards in the film have “007” as the design on their back. So Solitaire would have simply needed to look at the back of her cards to get Bond’s code number!

Another wonderful example of the iconography of the deck appearing in popular culture is within the video for Roseanne Cash’s song “The Wheel” (Sony BMG, 1993), which features live-action versions of over twenty Waite-Smith cards.49

Pamela’s Later Life and Religion

One of the last notable records we have of Pixie’s life immediately following her conversion to Roman Catholicism is in a letter from Lily Yeats (sister of Jack and W. B. Yeats) to her father, John B. Yeats in 1913. Lily reported that the change had affected Pamela’s social circle dramatically:

Pixie is as delightful as ever and has a big-roomed flat near Victoria Station with black walls and orange curtains. She is now an ardent and pious Roman Catholic, which has added to her happiness but taken from her friends. She now has the dullest of friends, selected entirely because they are R.C., converts most of them, half-educated people, who want to see both eyes in a profile drawing. She goes to confession every Saturday—except the week I was there—she couldn’t think of any sins, so my influence must have been very holy.50

25. Pamela Colman Smith in The Craftsman, 1912. (Photograph courtesy of authors, private collection.)

Conclusion

Pamela was a curious creature, amongst the last of the bohemians, the last of the Arts and Crafts movement. She appears to have eventually removed herself from people and art in favour of solitude and religion. However, so little is known of her later life that we can only surmise a few gleanings from the record of her death, not the life that immediately preceded it. Her story is incomplete, yet the tarot she designed and painted is its most complete legacy, a soul’s landscape and the land of the heart’s true desire.

Timeline: (Corinne) Pamela (Mary) Colman Smith

Whilst there are many overlaps in Pamela’s interests and working life, we have grouped her timeline into five phases for simplicity and specifically to highlight key times of interest to us. This is not a complete biographical timeline; however, as one is being created online with original sources and primary reference material. 51

Childhood and Early Adulthood (1878–1899)

Theatrical and Artistic Life (1900–1909)

The Tarot Years (1909–19)

After the Tarot and Catholic Life (1909–1918)

Later Life (1918–1951)

1878: February 16, born at Belgrave Road, Pimlico, London, England.

Parents: Charles Edward Smith and Corinne Colman (US citizens).

1881: April 3: English census, three years old and known as Corinne Pamela, recorded as living at “Oakhurst,” Fielden Park, Didsbury, Manchester, England with her parents, Charles Edward Smith (merchant) and Corinne Colman Smith. Parents born in New York and Boston. This area of Didsbury, Manchester was known at the time as being popular with the merchant class.

1888: December 17: The Smith family relocates to New York, arriving on the passenger ship Etruria from Liverpool. Pamela is eleven, her father, Charles Edward Smith, is forty-three years old, and Corinne Colman Smith is forty-two years old allegedly.

1893: Pamela sails from Kingston, West Indies, with her mother for New York; arrives October 4.

1895: October 30: Aged seventeen, Pamela arrives in New York from Kingston, West Indies on the passenger ship Alleghany, accompanied by her mother, who is recorded as being a mere thirty-eight years old. No occupation for either is recorded. Both are recorded as “soujourning,” under the reasons for travel.

1896: Pamela’s mother, Corinne Colman Smith, dies in Kingston, West Indies.

1897: March 10: Pamela arrives in New York, from Satoon, West Indies, on the passenger liner Alleghany; she is travelling with her father.

1899: December: Pamela’s father dies suddenly in New York (obituary).

1901: English census, 14 Milborne Grove, South Kensington, London, aged twenty-three years, Pamela is recorded as a “visitor” in the household of the Davis family. She distributed The Broad Sheet, her collaboration with Jack Yeats from her home in Milborne Grove.

1904: Pamela is residing at 3 Park Mansions Arcade, Knightsbridge, London, SW. An advertisement appears in the final edition of The Green Sheaf

(no. 13) for Pamela’s business venture in hand-coloured prints, etc.

1906: October 2: Pamela arrives in New York from London (departed September 22) on board the passenger ship Mesaba.

1908: Pamela is living at 84 York Mansions, Prince of Wales Road, London, England (electoral voters register).

1909: January 28: Pamela sails on the passenger ship Minnetonka from London to New York. She travels first class.

1909: May 24: Pamela arrives in London, on the passenger ship Minnewaska; she travells first class. Pamela is living at the address below. See letter to Stieglitz. Exhibition of her work at the Steglitz gallery New York.

1909: Pamela is living at 84 York Mansions, Prince of Wales Road, London (electoral voters register). However, she visits Ellen Terry at Smallhythe throughout the summer, based on photographs and sketches.

1910: Pamela meets composer Claude Debussy (1862–1918).

1911: Still living at York Mansions address (electoral voters register). Converts to Catholicism.

1913: Illustrations in The Russian Ballet by Ellen Terry, and Bluebeard.

1914: Illustrations in The Book of Friendly Giants by Eunice Fuller. Final inscription appears in her personal visitors book, indicating that she didn’t care for people any more.52

1918: Moves to Parc Garland on the Lizard, a large house within walking distance of several coastal areas. This was at the same time women over the age of thirty got the vote in the UK, a major step forward in equal rights.

1926: Illustrations for The Sinclair Family, by Edith Lyttleton. At present we cannot find any further reference to this book or the twelve illustrations Pamela created for it.

1942: Moves to Bencoolen House in Bude. The property had several years before been advertising the services of the Rev. J. Allsop, who “coaches backward or delicate boys. Parents recommend.”53

1951: Pamela dies on September 18. The National Probate Register recorded the following: “Corinne Pamela Mary Colman of 2 Bencoolen House, Bude, Cornwall died 18th September 1951. Probate Bodmin, 13 November to George Lyons Andrew and Richard Hugh Studley Jones, Solicitors. Effects £1048 and 4 shillings 5 pence.” Stuart R. Kaplan wrote that she left her money to a friend.54