27

Water Your Garden

WITH ALL I had to celebrate in my own life, I felt that I should be happier. Perhaps I was choosing to operate at a cautious, steady emotional state to help cushion future blows. The consistent low-dose sadness that trickled through my veins seemed to act as a vaccine, immunizing me against future, deeper pain; it was the small tremor that staved off the devastating quake. The potential side effect was that if someday a chilly winter actually did set in, I would have no warm reserves. I went to see a therapist, although I was skeptical that he could ease my mind. Experts with impenetrable boundaries and forty-five-minute attention spans, whom I could not convert into peers, made me uneasy. Moreover, in order to help me, he would have to convince me that, despite all I knew to the contrary, the world was a safe place.

As I had suspected, the therapist did little to change the way I viewed the world. During one session, however, he did introduce a provocative word into my vocabulary: enmeshed. I was telling him that Mom felt excluded when my sister and I spent time together without her, when he matter-of-factly said, “You obviously have an enmeshed family.” I found myself shaking my head in agreement, although actually I had never heard the term enmeshed before. It just sounded like an apt description of my family. None of the high-achieving children had left the city for college. We saw each other multiple times a week. My brother David, in fact, had recently moved into my apartment.

A few days after this therapy session, over dinner with Mom and Dad at a local Italian restaurant, I floated the concept. “We’re an enmeshed family,” I calmly mentioned. I watched carefully for their reaction. Dad didn’t have one. He continued twirling pasta onto his spoon before inhaling it. Mom, in contrast, bristled.

“We’re not any more enmeshed than any other close family,” she said, setting down her fork so she could gesture with her hands. “Besides, you make it sound like it’s a bad thing,” she added. Mom can be a moving target in these disagreements. If she feels criticized, she will take my statements and, without hearing what I am actually trying to communicate, project her fears onto them. This keeps us from talking things through and coming to deeper levels of understanding. Consequently, Mom, my model for speaking one’s mind, doesn’t really allow me to do this with her. When it came to discussing our relationship, I, too, sometimes felt that a pillow was placed over my mouth.

“I’m just saying that’s what the therapist thinks. It’s an interesting idea.”

My new knowledge helped me to move forward. Maybe I would never feel that the larger world was a safe place, but mine was a friendly and enjoyable one in any event, and I would continue to make the most of it. At thirty, I purchased my first home. Then I fell in love with Cliff, twelve years after he had been my teaching assistant at UCLA. Boyishly handsome, with a warm, gentle voice and a slight gap between his front teeth, he had come across as smart and funny. The fact that he was my teacher, an authority figure to level, undoubtedly added to the initial attraction. As I sat in his First Amendment class, back in 1978, the thought had crossed my mind that someday, if I met a man like him, I might actually leave home and get married. I lingered after class to ask questions and make (what I hoped were) witty remarks, and while, unfortunately, Cliff never displayed any signs of romantic interest in me, we had developed what turned out to be a lasting friendship by semester’s end.

After that, once a year or so we would catch up over a lunch or dinner. When I was in law school, Cliff got married. My new boyfriend, whom I had met while summer clerking, and I were guests at the wedding.

Seven years later, in the fall of 1990, Cliff told me that he and his wife had separated. By then he was an entertainment lawyer, and our paths had crossed professionally from time to time. Our ensuing dinner at a local French bistro seemed surreal. Cliff and I talked easily about work and travel and his four-year-old son, Christopher.

“Let me ask you something,” Cliff said toward the end of dinner. “Are there men you wish you dated but never did?”

Was he saying he had noticed me all those years ago? “Are there women you wish you had dated?” I responded.

He looked up at me and smiled shyly. Without ever answering the question, he left me wondering, Could I have been right, all those years ago, about him being the kind of man I could marry?

Cliff came by my home the next day, with Christopher in tow. The beautiful boy with straight black hair and clear olive skin brought me a flower, and we looked at my baseball cards together. A series of dates followed, and then a romantic weekend getaway, over which we slowly got to know each other after twelve years of sporadic conversations.

By this time in my life I had endured countless dates during which men speculated as to why I did not want to rush into relationships—“I can see you’re a workaholic” “You obviously have fears of commitment” “My sister is gay. I bet someday you’ll realize that you are, too” “Who’s the other guy?” I would smile; I would laugh; I would nod sympathetically. But I couldn’t wait to get back home from my date, alone. I liked befriending a man first, even pursuing him, before he began maneuvering around boundary lines that I had carefully constructed decades earlier in self-defense.

Cliff and I had begun dating in September. By the time January rolled around, we were officially a couple. One evening, I hosted a salon of sorts on contemporary spiritual issues. The moderator was a rabbi, Laura Geller, whom I had met through a liberal Hollywood women’s political organization. Fifteen or so friends had come over that evening, as had my parents. Cliff was there, too, but less out of interest in the topic at hand than to be supportive, and to meet my parents for the first time.

“So what did you think of my mom and dad?” I asked Cliff as soon as everyone left.

“I didn’t get to talk to them much, but they seem very nice. I liked them.” He was helping me push chairs back into place.

“That’s it? No other observations?”

“Well, your dad seemed very helpful. I noticed he carried all the trash bags outside afterward.”

“He always does that. He’s the nicest man. Did you talk to my mom at all?”

“Not really. But I could tell she is interesting and has a lot of opinions.”

I had not worried about their first encounter. Cliff and my sister, then a feature film executive, had already become fast friends, and Cliff had also gotten the green light from my brother, who recently had moved up to San Francisco. I assumed all would go just as smoothly between Cliff and my parents. Had things not gone well, however, it probably would not have boded well for our long-term relationship. Not only would I have questioned Cliff’s judgment if he had been critical of my parents, but the risk of having to choose between a man and my parents would have been too threatening.

“Your parents seem to have a good relationship,” Cliff then added.

“Yeah, I guess they do.” Actually, I had never thought that my parents were perfectly suited for each other. Mom enjoyed going to the theater, reading novels, dining on gourmet foods, preferably in exotic locations, and making up for a lost childhood by experiencing as much as possible. Dad loved being surrounded by our family, either out at a favorite restaurant or at home. He was in his element eating spaghetti with canned tomatoes, developing photographs in his darkroom, and reclining on the Barcalounger watching television. Mom was wise, intuitive, and edgy; Dad, pragmatic and logical, yet accepting. Mom asked how we were feeling, while Dad focused on what we were doing. Mom also looked for opportunities to express her feelings, regardless of the argument that might ensue, while Dad preferred resolving disputes quickly and painlessly, if they didn’t just disappear on their own. Their differences were numerous, and yet they stuck together like stamps on an envelope. Their bond of deep love and friendship was a testament to the potential in marriage for the sum to become greater than the parts.

The next morning, I called Mom first thing, on my way to work. “So?”

“So what?” she said. I could hear the amusement in her voice.

“You know. What did you think?”

“He seems very nice. And he’s handsome. He’s obviously very smart.”

“What else?”

“What else do you want me to say? Are you serious about him?”

“I don’t know. Maybe. But I wanted to hear your impressions.”

“Dad and I liked him. That was our impression,” she said, laughing.

I was relieved to have my parents’ approval. Over the next few months, I came to adore Cliff. We shared so many interests, we had so much fun together, and he was such a good person. His happy, passionate disposition was a good balance for mine, which tended to be more contemplative and rational. Particularly after a failed marriage, Cliff valued putting effort into maintaining a strong relationship. He accepted my family, and never acted as if he was in competition with them for my affection. Cliff loved children, and I adored his son, Christopher. Cliff was also respectful of boundaries. He never pressed me for details about men in my past, some of whom he was likely to have heard rumors about in the insular, gossipy entertainment world. I felt more at home with him than I ever had in a romantic relationship. In Cliff, I finally found the organization I wanted to join. So I should have been ecstatic on that midsummer evening in 1991 when Cliff asked me to marry him.

From the outset, his behavior was unusual. He hadn’t wanted me to invite friends to join us, and he had brought his own bottle of champagne to the elegant restaurant. As we conversed in the intimate dining room, he seemed preoccupied. I tried to convince myself that I was imagining things. But what if I’m not? Please don’t ask me. Not yet. Not tonight. Then he reached into his pocket and withdrew a small box, which he placed in front of me. Everything slowed down and became a little fuzzy.

“Liesl?” Cliff had a nickname for everyone, and mine was Liesl, the name of the eldest daughter in The Sound of Music. Cliff said I reminded him of her, particularly with my family history. In any event, our names were similar. “Will you marry me?” he asked.

As I gazed into his soft, hazel-brown eyes and smiled back, my mind began to race. Was Cliff really asking me to marry him? This was the moment I had been hoping for. I opened the box and stared at the deep blue sapphire, set in a gold band. It sparkled before me, seductive and confident, eager for me to behold its beauty. It was too good to be true, and yet I sat, still and quiet. How could I get married? I already had a family. How could I love anyone else as much? How could I handle being needed by anyone else as much? For Mom, marriage had offered the hope of escape from her family problems. For me, it conjured up a spirit of confinement. I had worked so hard to become independent. I wanted to remain that way. Yet I loved this man. How could I say no? Were it the other way around and he turned me down, I’d be devastated.

After one of those moments in which you pack all of your inadequate wisdom into the pause between question and response, I heard myself tell Cliff, “I love you. I think I want to marry you” (or maybe I whispered “think”—or said it to myself). “But…I don’t feel like I’m ready to actually wear this ring, to wake up tomorrow morning officially engaged.”

I looked into his eyes, hoping he wasn’t crushed. Or angry. He was actually pulling something else out of his jacket pocket. And to my great relief, he was smiling.

“I thought you might feel this way,” he said. “So I had a contingency plan.” He set another box, this one long and narrow, in front of me. “Open it,” he said.

I found a delicate sapphire tennis bracelet inside. “Put it on,” he told me. I did. “Every time you look at it, remember that I want to marry you.” I could not have hoped for a more loving response. As he helped clasp the bracelet, I summoned the nerve to ask, “What about the ring?”

“Put it away until you’re ready to wear it,” he said. I loved him even more.

At home, wanting to keep the ring that did not yet feel officially mine in a safe place, I wrapped it in a sweat sock and hid it inside the carved wooden Chinese trunk that sat at the foot of my bed. Every once in a while I took it out to show a friend, or just to admire. I began to watch Cliff carefully, with an eye to how my life would change if I were to marry him.

Over Labor Day weekend, Cliff, Christopher, and I traveled to Maine to visit my best friend from law school, Barbara, and her family, and then to Vermont, where we stayed with my guardian angels, Diana Meehan and Gary Goldberg. Everyone got along famously. Back in Los Angeles on Tuesday morning, six or seven weeks after Cliff had popped the question, I awakened at peace with a decision. I knew that my friends would not disappear, my parents would survive, and Grandmother Leah would remain a part of me. As Cliff and I left my home that morning to go for a jog, I stopped at the white picket fence that bordered my front yard and turned to face him.

“Look, we’re engaged,” I said, holding up my left hand to display the sapphire ring I had slipped on moments earlier.

“We are?” he asked, caught off guard.

“Yes. I love you.”

From the first moment, I knew it was the right decision. After returning home from our jog, we immediately called our parents, all of whom were very excited. In fact, mine were ecstatic, although not weepy. Mom and I had never shared a teary moment of unadulterated happiness. We contained our tears, like camels carrying water in the desert, knowing we might need them in the future.

“Can we take you to lunch to celebrate?” Dad asked.

“Sure, Franco,” Cliff said, invoking his nickname for Dad and laughing because he had anticipated the proposition. The two had already become great friends and looked forward to celebrating every occasion with a festive meal. They also, I imagine, recognized in each other a respect for the complicated women in their lives. These intense women seemed to complement their own, less angst-ridden approaches to life.

Cliff and I were married four months later, on a Saturday night in January. At the ceremony beforehand, where we signed our ketubah, or Jewish marriage contract, in the presence of our parents, siblings, Christopher, and a best friend apiece, Rabbi Geller asked if anyone had advice for us. Mom spoke up first.

“Cliff and Leslie, my advice to you is to water your garden often.” Everyone nodded in agreement and chuckled, wondering precisely what Mom had in mind. In the ensuing years, Cliff and I would come to fully appreciate the wisdom in her comment. We surprised ourselves by how many times, with Mom’s words hanging in the air, we reminded ourselves to take a break from work or children and, at least for the evening, focus on each other and on watering our garden.

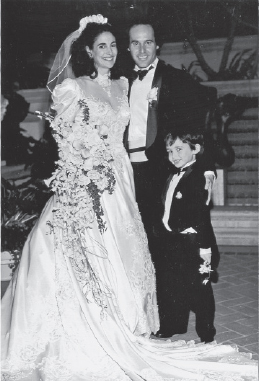

Leslie, Cliff, and Christopher in wedding photograph, 1992.

As the string quartet played Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, I walked down the aisle between my parents. How comforting that was. How secure I felt entering my new phase of life. How different from what Mom had experienced thirty-four years earlier. I glanced sideways down the rows of chairs and noticed Cliff’s friends and family, and all of mine, whom I had felt free to invite. I smiled at Dad’s brother, Uncle Buddy, and Mom’s siblings, Auntie Sandra, Uncle Sam, and Uncle Brad, as I glided by. Clara was there, too, still part of my family. I looked up ahead and saw my sister and brother, my maids of honor, and my bridesmaids—my cousins Karen and Lauren, and seven of my closest friends. Although I rarely spent as much time with any one of them as I would have liked, each made my life better, and I took comfort in their numbers. At least I would never feel utterly alone, as Mom had felt. Finally I stood beside Cliff, under the chuppah, and I knew everything was right.

At the reception afterward, Mom seemed to have the most fun of anyone. She truly appreciated life’s celebrations. Gwyn, on the other hand, was uncharacteristically subdued. She feared losing her only sister to Cliff, or, as she called him, her BIL (brother-in-law). I spent the evening on task, circulating from table to table, greeting our nearly three hundred guests. I looked forward to attending someone else’s wedding in the near future, so Cliff and I could finally have an uninterrupted dance together.