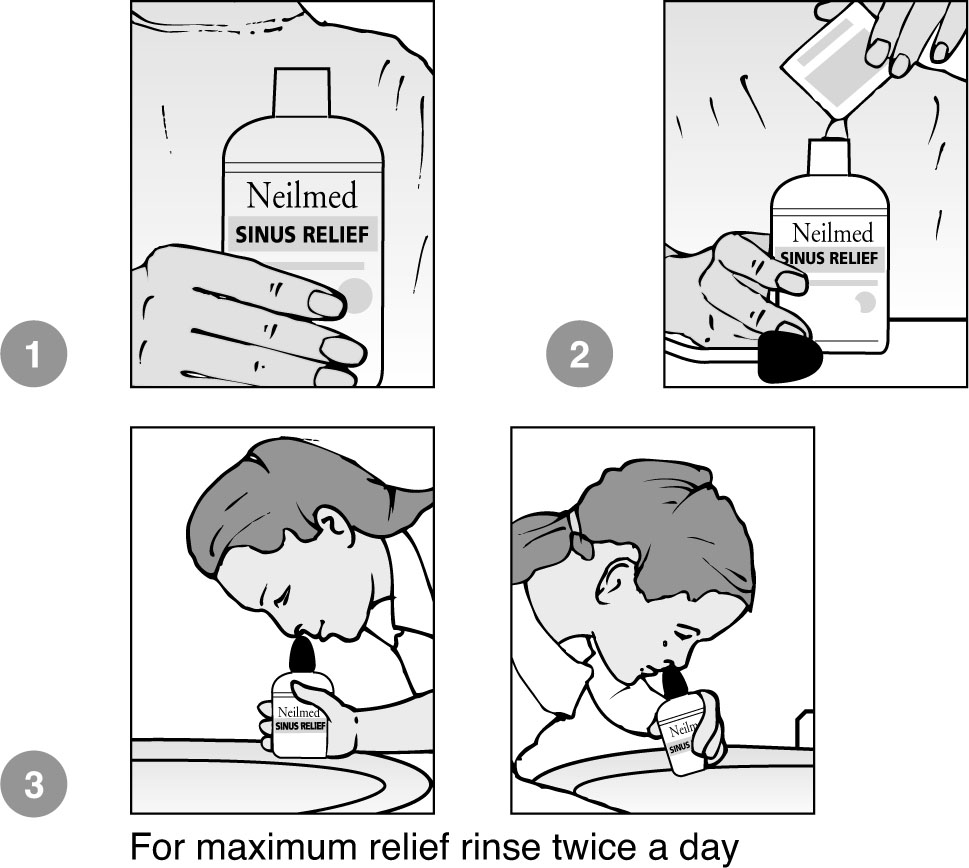

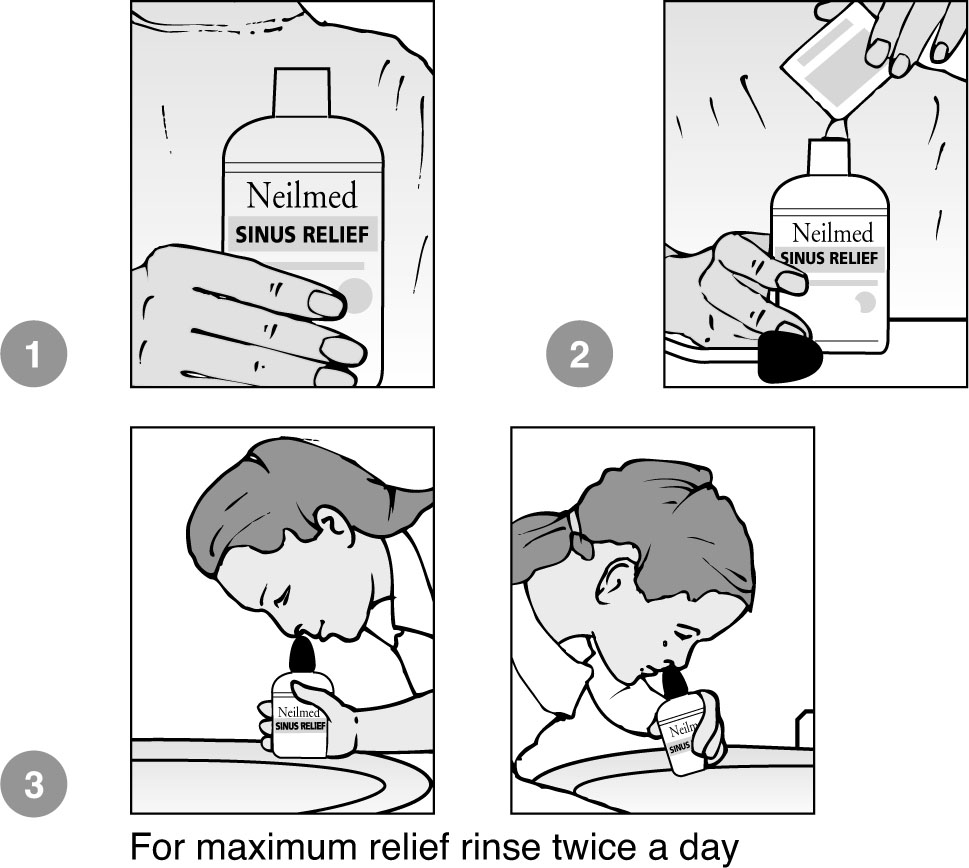

Figure 10.1 Sinus irrigation

A better way to keep your nose and sinuses healthy

Blowing your nose to relieve the stuffiness caused by hay fever may be second nature, but some specialists in ear, nose and throat disorders argue it reverses the flow of mucus into the sinuses. It also slows the natural drainage of the sinuses.

To test the concept, infectious disease investigators at the University of Virginia in the USA conducted CT scans and other measurements as subjects coughed, sneezed and blew their noses. In some cases, the subjects had opaque dye dripped into their rear nasal cavities.

Coughing and sneezing generated little if any pressure in the nasal cavities. But nose blowing generated enormous pressure – ‘equivalent to a person’s blood pressure reading’, one researcher said – and propelled mucus into the sinuses every time. The same doctor said it was unclear whether this was harmful, but added that during illness it could shoot viruses or bacteria into the sinuses and possibly cause further infection.

Conclusion: blowing your nose can create a build-up of excess pressure in the sinus cavities.

According to experts in the Ear, Nose and Throat Department at the New York University Langone Medical Centre, the correct method is to blow one nostril at a time and to take decongestants. This prevents a build-up of excess pressure. So what do you do if you’re troubled with nose problems and experts warn against that most traditional of remedies for relief, blowing the nose? You should consider nasal lavage (also known as nasal irrigation, nasal douching or sinus rinsing).

The principle of sinus irrigation

While some level of mucus production from the nasal and sinus lining is normal, allergies (such as hay fever) and sinus infections can cause excessive mucus production. This excess mucus causes nasal and sinus symptoms such as a runny and stuffy nose or post-nasal drip. The key to symptom relief is to physically wash away from the nasal passages this excess mucus and the associated allergens, such as grass and tree pollens, dust particles, pollutants and bacteria. Rinsing in this way will reduce inflammation of the nasal membrane, allowing you to breathe more normally. In summary, nasal lavage:

All that’s involved is squirting a solution of slightly salty water up your nose, letting it drip out, blowing your nose gently, then repeating. The mechanical action of flushing out thickened mucus cleanses the nasal passages, making it easier for the cilia, the tiny hair-like structures that line the nose, to push the remaining mucus out.

There is strong support for nasal lavage among allergists and ENT specialists. ‘Many patients who have sinus disease, allergies, or chronic infections are improved tremendously by lavaging their nose out once or twice a day,’ says a top USA-based ENT specialist. ‘And for those who have had surgery to open up narrowed sinuses, regular cleansing is a must. The main improvement they experience is the ability to wash out the cavity.’

‘Even if antibacterial medications are added to the lavage solution, most of the benefit is from the mechanical rinsing of the nasal cavity,’ says yet another ENT specialist at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary. ‘Among other things, the gunk you rinse out in mucus includes natural chemicals called cytokines, which promote inflammation. If you remove the mucus, you can actually reduce the inflammation.’ He emphasizes that the way to do this is with salty water.

While large, controlled studies of nasal lavage for treating and preventing colds and sinus infections are hard to come by, the little data that does exist seems to support the practice. One study of more than 200 patients published in 2000 in the journal Laryngoscope found that after three to six weeks of nasal irrigation, patients reported statistically fewer nasal symptoms. A 1997 study of 21 volunteers in the same journal found that lavage improved the speed with which nasal cilia were able to move mucus along. A 1998 study in children published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology showed that lavage is ‘tolerable, inexpensive, and effective’.

Effective nasal irrigation devices must have the following:

Neilmed Sinus Rinse ticks all the boxes for success. It’s essentially a plastic squeeze bottle that holds 240 ml of liquid. With it come small sachets that contain salt and baking soda granules in an isotonic combination ideal for nasal irrigation. To use, you boil a kettle of water and let the water cool until it is just warm. Empty one sachet into the squeeze bottle and top up with the warm water to the level on the side. Make sure the granules are dissolved. At the top of the black cap on the bottle is an opening. This is held against one nostril opening (see Figure 10.1), with your head slightly tilted forward over a wash basin. Squeeze the bottle firmly: one half of the contents should go up one nostril and come down the other side. Pause, blow the nose gently and repeat the procedure on the opposite nostril. This washes the nose and sinuses clean, and clears snotty debris as well as allergens such as tree and grass pollens, bacteria, viruses, etc. that may be lurking on the nasal lining. The salt and baking soda combination is remarkably refreshing for those with sinusitis and they are delighted with the non-medical components of the product.

Figure 10.1 Sinus irrigation

Nasal irrigation is more or less the mainstay of treatment for people who have had sinus surgery, but it’s something to recommend as a daily routine for anyone troubled with nasal issues of whatever cause, including pollen hay fever. In the USA, it’s considered almost as important as brushing your teeth and combing your hair before going out for the day. Consider it as dental floss for the nose and sinuses.