Conclusion

Tributes

Although Malone told his beloved Ida and others on many occasions that he was confident that he would survive the war, he told a friend just before he left New Zealand that: ‘Something tells me I shan’t come back here, that I will go out’.1

The death of Malone, who Charles Lepper described as ‘one of the bravest men I ever saw’,2 was keenly felt within the battalion. It was to many in the Wellington Battalion emblematic of the destruction of their unit at Chunuk Bair.3 Major-General Godley praised Malone both in public and in private. In one letter to an acquaintance in New Zealand he wrote: ‘Poor Malone was the gallantest soul in action that ever walked, and his men would follow him anywhere. He was killed at the head of his battalion at the highest point which we attained, and literally in the very forefront of the battle, and lies now in a Turkish fort on Chunuk Bair, which he captured from the enemy – a more fitting restingplace [sic] for such a gallant soldier I cannot imagine.’4 His wife Lady Louisa Godley also thought well of Malone. In a letter to her husband on 11 August, she remarked that ‘Major Fitzherbert rang up to tell me that there had been a lot of casualties in the N.Z. force, and amongst them Colonel Malone killed. I am very sorry – he was a gallant fellow and was keen about his men and work. I know how you will miss him and the force will be the poorer of a good officer.’5 After she learned of Malone’s death Lady Godley wrote a letter of condolence to Ida.6

Ida Malone was devastated by the news of her husband’s death, which she probably received in a telegram on 9 or 10 August.7 She must have derived some comfort from the many condolence letters she received. One of the first was from Edward Harston, who wrote on behalf of the Wellington Battalion:

The sentiments in Harston’s letter are also expressed in Birdwood’s condolence letter, written only a day after Malone’s death:

A few years later Birdwood told one of Malone’s sons that his father was a ‘matchless’ battalion commander. Birdwood developed a high opinion of Malone and considerable affection for him. His work at Quinn’s Post especially impressed Birdwood, who remarked that Malone ‘thought out every necessary detail and by his determination and driving power saw that what he realised was necessary should be done’.10

Brigadier-General Johnston, with whom Malone had often clashed, wrote that he ‘was such a thorough soldier and good comrade that he had endeared himself to all of us’.11 Godley wrote, in a brief but clearly heartfelt letter, that ‘He was the most valiant soul I think I have ever known ... I would sooner have lost a battalion than him.... I cannot say how much I owe him personally. His loyalty and support to me both in New Zealand and here has been unfailing. I have lost one of my best friends and my sympathy for you is more than words can express.’12 Sir Thomas Mackenzie, the New Zealand High Commissioner in London, whose son was blinded in August while serving with the Wellington Mounted Rifles, told Ida that her late husband had been ‘one of the finest soldiers who ever fought for New Zealand’13 and that he had ‘left a great and honoured name behind him which will ever live in the memory of us New Zealanders’.14 Included in the condolence letters from New Zealand was one from the Stratford Parish Committee which, like Johnston, remarked on Malone’s strong Catholic beliefs, noting: ‘As you know, Colonel Malone was one of the oldest and most highly esteemed of our parishioners and was both consistent and practical in his observance of the duties and obligations of our Faith, and, no less in his dying than in the manner of his living he was an inspiration to us all.... In cases like these we may repeat Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori.’15

Malone’s death was announced in a casualty list released in New Zealand on 12 August.16 This list was the first in a series of unprecedented size that made the full extent of the losses suffered by the NZEF in the August offensive clear to the New Zealand public. Prime Minister William Massey commented on the loss of so ‘many of our brave men’ which he described as:

New Zealand newspapers widely reported Malone’s death and many carried obituaries praising his achievements and noting his fine qualities as a soldier and a man.18 Naturally, however, it was in Taranaki where his death was most keenly felt. The Taranaki Herald described him as ‘one of the best known men in Taranaki’ and noted that at Gallipoli ‘he was making a mark as a leader, who, while willing to take every risk himself, was always careful not to expose his men to unnecessary risks. His loss will be keenly felt by the regiment, for it is certain that had he been spared he would have made a great name for himself as a soldier.’ New Plymouth’s newspaper concluded its lengthy and very positive obituary by stating that: ‘The news of Colonel Malone’s death in action caused quite a gloom locally when it became generally known this morning.’19 Malone’s demise was even more acutely felt in Stratford where the news was received via a telegram from Ida Malone. The Stratford Evening Post noted in a lengthy obituary that he had a ‘wide circle of friends’, described him as ‘a true sport’ who ‘was brim full of enthusiasm, a keen soldier, a splendid disciplinarian, a magnificent organiser,’ who was ‘undoubtedly endowed with a thorough military genius’. In his civilian life the obituary stated he was a mainstay of a range of local organisations and activities. He was ‘conscientious, painstaking and thorough’. Malone was said to possess ‘exceptional abilities ... As a farmer, a businessman, a lawyer, and a soldier, he filled the bill in every sense. Mr Malone proved himself a true gentleman, a loyal friend and honourable foe, and to those who were privileged to know him intimately for any length of time these characteristics were outstanding.’20 Posthumously Malone’s ‘noble example’ was used to encourage recruiting and to castigate those who shirked their duty.21

There is no doubt Malone was a formidable character, a ‘rugged figure, a typical old New Zealand pioneer with a powerful jaw and an appearance of great strength and determination. He had a forcible character.’ The Wellington Battalion ‘was Malone’s battalion and every man in it breathed the spirit of Malone and had been moulded according to his ideas.’22 The strong foundations laid by Malone stood the Wellington Battalion and later the Wellington Infantry Regiment, which subsequently comprised up to three battalions, in good stead. Throughout its existence, the regiment exhibited the ‘happy combination of a reasonable discipline – not enough to prejudice initiative, but sufficient to get the maximum team result.’23 The officers and men who had served with the regiment commissioned a memorial plaque to Malone and the other battalion commander to lose his life in the war, Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Cook, DSO, in All Saints Church in Palmerston North. The regiment’s colours had earlier been laid up at this church.24

The respect and affection the men of his battalion felt for their ‘old’ colonel is evident in the description of Malone in The Arrower’s [The Arrower was the magazine produced on board the Arawa] official Botanical Catalogue: ‘Abies Malonia: A magnificent tree of the colonel species; very hardy and of striking appearance; does best in clean sand and scrub.’25 The special place Malone had in the memory of the Wellington Regiment veterans was demonstrated by the opening of the Malone Memorial Gates at the entrance to King Edward Park in Stratford on 8 August 1923. The gates are one of the most substantial memorials to an individual serviceman ever erected in New Zealand, and were paid for by former officers of the regiment and a variety of other supporters. At the well-attended opening ceremony, Lieutenant-Colonel Cunningham spoke about his old commanding officer, saying: ‘in camp at Awapuni, ... they soon found that he meant to make soldiers of them. They at first disliked him, but later learned to respect him, and finally came to love him for a man who could be relied on, although they knew he was determined to try out every man who came under him and remove the soft spots from them. He knew war would be a hard business, and made up his mind that the regiment would be fit when it had to take its part.’26 It is a measure of the ‘great respect and love’ his men had for him that on the 50th anniversary of his death a former member of Malone’s battalion remarked that he ‘was the embodiment of the spirit of Anzac’, that the efficiency of the unit and its military prowess were in large part due to his example, professionalism and leadership.27

Fred Waite’s official history, The New Zealanders at Gallipoli, published in 1919, describes Malone as ‘one of the striking characters in the New Zealand army’ and praises his outstanding leadership.28 Malone’s contribution is well recognised in the regimental history, The Wellington Regiment N.Z.E.F., 1914-1919, which was published in 1928. Cunningham, who wrote the chapters dealing with the first year of the regiment’s existence, had access to Malone’s diaries.29 Both Edmond Malone and his father are commemorated in Stratford’s unique Hall of Remembrance, which contains photographs of the more than 180 men from the Stratford district who died in the Great War.30 In November 2011, a life-size bronze statue of William Malone by Fridtjof Hanson was unveiled on the main street of Stratford. The erection of the statue was the product of years of work by a group of local people, the Malone Quest Committee.31

Impact on the Family

Throughout New Zealand, families were torn asunder by the Great War. In the case of the Malone family, the death of William George Malone and related events left the family scattered between England and New Zealand. Before August 1914 the Malone family had been one of the most prominent in the Stratford community. After that date, only Brian and Terry Malone seemed to have lived for any length of time at all in Stratford district. Ida and her three young children and Norah Malone remained in England, and only Denis ever returned to live in New Zealand. Norah visited New Zealand shortly after the end of the First World War and in the 1960s.32

Ida Malone mourned her much loved husband until her own death. She showed that she was in mourning by dressing exclusively in black and later grey clothes.33 After Malone’s death Ida made an effort to ensure that his life and achievements were remembered. Late in 1915 she corresponded with the Australian war correspondent, Ashmead-Bartlett, who had taken several photographs of Malone during his visit to Quinn’s Post.34 She was also in touch with William Whitlock of the Hawkes Bay Herald-Tribune, and provided him with copies of a number of letters she had received relating to Malone’s service at Gallipoli. She probably got in touch with Whitlock through Brian Malone, who may have worked as a reporter on the Herald-Tribune. Whitlock suggested to the government that something should be done to commemorate Malone, stating that such an initiative ‘would be very pleasing to the family and very acceptable to Taranaki where he was a soldier idolised.’35 The suggestion was considered by the Cabinet on 22 December 1915, but no action was taken.36

In 1921, Ida sent some of William Malone’s writings and photographs to Sir James Allen, New Zealand’s High Commissioner in London. Allen, who had been Minister of Defence during the Great War and whose son had been killed at Gallipoli, wrote that: ‘I cannot convey to you how deeply impressed I have been with all that I have read. Your late husband reveals himself in this correspondence as a noble man, an enthusiastic and lovable soldier, and I can well understand how those who were under his command came to like and trust him. You know how fully I sympathise with you in this great loss, and I realise how much our own country has suffered because Colonel Malone has gone from us.’37

Malone attached great importance to the financial security of his wife and family, and it is clear that on Gallipoli, particularly near the end of his life, took some solace from what he believed to be the sound provisions he had made for them. He left an estate valued at more than £25,000, the equivalent in today’s terms of more than $3,400,000. The principal provisions of this will, which was prepared in August 1914, left Mater all his personal property, the right to live at ‘The Farlands’ and half the income from the estate for the rest of her life or until she remarried. The estate was then to be divided, with half being shared among his children from his first marriage and half among the children from his second marriage. Harry and Charles Penn were the executors of the will and trustees of the estate.38 Initially, Ida Malone received an income from the estate of between £150 and £240 a year, which combined with her war widow’s pension from the New Zealand Government of £249.12, gave her an annual income of between £400 and £490. She found this inadequate and asked the trustees in 1922 for capital payments of £100 per annum for her two younger children.39 New Zealand was affected by a severe economic recession after the end of the First World War that was caused by a collapse in agricultural prices. Efforts by the Penn brothers to recover money owed to the estate met with little success. The recession greatly reduced the income of the Malone estate, the major asset of which was farmland. The situation of the Malone estate was, it appears, made worse by the fact that Malone had personally guaranteed mortgages to people who became insolvent. By 1924 Ida Malone was receiving an allowance of only £40 each year from the estate. Ida Malone was placed in such a difficult financial position by these developments, that she was unable to purchase a home and lived a peripatetic existence in rented rooms or cottages. She was obliged to sell her jewellery and was unable, as she wished, to visit New Zealand.40

Ida Malone’s situation was made even worse when she lost her personal effects. Norah Malone packed the effects during a visit to New Zealand in the 1920s and arranged with the Penn brothers for them to be sent to England. It appears Norah wrote to Ida telling her that the items were on their way, but this letter never seems to have reached Ida Malone and after sitting on the wharf in England for a year the personal effects were returned to New Zealand. Brian Malone then decided to sell the effects to recoup the shipping costs. This incident indicates the extent to which the English and New Zealand parts of the Malone family had by the 1920s become estranged from each other or had simply lost contact.41 Ida faced her problems with considerable fortitude, and although she suffered from health problems, did her best for her children. She is remembered by her grandchildren as a generous, affectionate and cheerful woman whose life was blighted by her husband’s death and her straitened circumstances. Before the Second World War, Ida Malone was allocated, much to her relief, a small cottage for war widows in Morden, Surrey. She died in 1946.42

Norah Malone was on very good terms with her stepmother and remained in the United Kingdom for most of the rest of her life. During the Great War she served as a Red Cross nurse. Norah Malone later married a British Army officer and died in Scotland in 1983. After her husband’s death, Ida Malone was not in a position, because of ill health and financial concerns, to look after her youngest child Molly who was sent to a convent at the age of five. Molly Malone later lived with her mother until her marriage in 1938 and again briefly during the Blitz on London. She died at the age of 69 in 1979. Barney and Denis Malone were sent to boarding schools and, like their sister, suffered from homesickness and a general feeling that their childhoods had been irretrievably damaged by the loss of their father.43

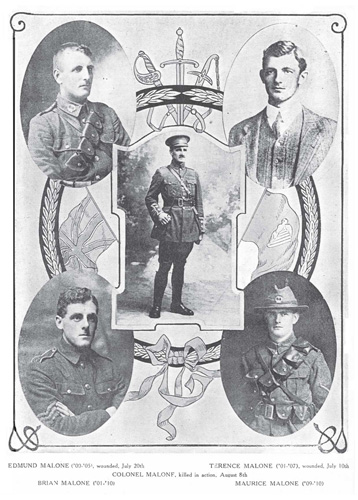

Edmond Malone, William George Malone’s oldest son, was wounded in the leg on 20 July 1915. After being evacuated from Gallipoli, Edmond was sent to England for further treatment and then returned to Egypt and his unit, the Wellington Mounted Rifles, in January 1916. After William Malone’s death, Brigadier-General Johnston apparently recommended that both Edmond and Terry receive commissions in their father’s old unit. The severity of the wounds Terry received at Gallipoli ended his military service, but in March 1916 Edmond was commissioned as a second lieutenant and posted to the 1st Battalion of the Wellington Regiment. Between April and early June 1916 Edmond served with his battalion in France. He was then either taken ill or possibly wounded, and invalided back to England, where he remained until October 1916.44 At this time Edmond was described by his commanding officer as a ‘willing officer but without much experience’.45 Sometime during his period in hospital in England, Edmond met and fell in love with a nurse, Mary ‘Peter’ Brocklehurst. They were married at Watford on 4 July 1917. In October 1917, by which time Edmond had been promoted to lieutenant, he suffered a severe gunshot wound to his right shoulder and was again sent to England for medical treatment. In November, Edmond was awarded the Military Cross for ‘conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty’ while leading his platoon in an attack through ‘heavy shell and machinegun fire. He set a splendid example of courage and energy to his men.’46

Edmond returned to his unit in France in February 1918. Late in the following month, during heavy fighting to halt the German Spring offensive, he suffered a grave wound to his left leg. A few days later, on 6 April 1918, Edmond Malone succumbed to this wound.47 He was a popular and dedicated officer whose death was keenly felt by his comrades.48 At the time of her husband’s death, Mary ‘Peter’ Malone was pregnant with their daughter Elinor, who was always known as ‘Petie’.

In 1945 after the end of the Second World War in Europe, one of Terry Malone’s sons, Desmond Malone, who had been serving in the New Zealand forces in Italy, went to the United Kingdom on leave and decided to visit his aunt. Mary ‘Peter’ Malone had never remarried, and at her house she showed Desmond Malone his uncle’s lemon squeezer hat and Military Cross, which were beside her bed, a position that they had occupied since 1918.49

Edmond Malone’s lemon squeezer hat is now in the collection of Puke Ariki Museum in New Plymouth. It was donated to the museum in 2009 by Laurence and Ray Roebuck. They had been given it by Petie Malone’s granddaughter, Mary Deighton. Laurence and Ray Roebuck are the sons of Robert Bryan (known as Bryan) Roebuck who was born in July 1912 and was, it appears, the illegitimate child of Edmond Malone and 19-yearold Gladys Roebuck. After his birth, Bryan Roebuck was adopted by his grandparents and bought up as their son. His real parentage remained a secret within the family for many years. Gladys Roebuck and Edmond Malone were, the family understand, briefly engaged, but the match was opposed by the Malone family because the Roebucks were Methodists.50 This engagement may be the one William Malone refers to as having been broken off in his letter to Ida Malone of 23 July 1915. Bryan Roebuck was born in Okato on the coast south-west of New Plymouth where his mother, her family and Edmond Malone were living. Okato is a small settlement and it seems unlikely that Edmond Malone could have been ignorant of the fact that he had fathered a son. There is no evidence that William and Ida Malone knew of the existence of their grandson.51 In 1999, the Okato Returned Services Association decided to mark Edmond Malone’s death with a memorial plaque on the Okato War Memorial. The plaque was unveiled at a ceremony attended by members of the Malone family on 11 November 1999.52

Puke Ariki also has in its collection Edmond Malone’s military compass. As with the lemon squeezer hat, there is an interesting story behind the museum’s acquisition of this item. The compass was in a box of militaria purchased at an auction in 2009 by English art dealers David and Judith Cohen. They later noticed that it had ‘EL Malone 1st WIB NZ Division’ faintly inscribed on its leather case. The Cohens showed the compass to their friend Dr Christopher Pugsley, an eminent New Zealand military historian. Dr Pugsley’s face apparently went white when he read the inscription on the compass. Once he explained the significance of the compass to the Cohens, they gave it to him. He at first intended passing the compass to Dr Judy Malone in Wellington. Dr Malone, however, felt strongly that the compass should go to Puke Ariki. Dr Pugsley agreed to this and donated it to the museum in 2010.53

Brian Malone had been working for his father as a clerk when he enlisted in the force dispatched in August 1914 to seize German Samoa. He returned from Samoa in November 1914 and was discharged from the New Zealand Expeditionary Force.54 Not long after his father’s death, Brian Malone noted that all four of William Malone’s older sons were serving or were about to serve, in the NZEF, and that Norah was serving as a Red Cross nurse. He remarked that ‘if there were more of us they’d be in it too’.55 After returning from Samoa and while waiting to serve again in the NZEF, Brian worked as a journalist in Hamilton and later in Hawke’s Bay. In January 1917, he was found to be unfit for service in the NZEF because of defective eyesight. Six months later, however, he passed a medical board and was re-enlisted in the NZEF. On this occasion he served in the New Zealand Medical Corps in New Zealand and on hospital ships returning wounded and sick NZEF personnel to New Zealand. He was discharged from the NZEF in October 1918 because of his defective vision.56 Brian later became a lawyer in Te Awamutu. He died in Tauranga on 21 December 1967. One of his sons, the late Edmond ‘Ted’ Malone took a great interest in his grandfather’s life. Ted Malone’s widow, Dr Judy Malone, who like her late husband is an historian, has also undertaken extensive research into the Malone family.57

Terry Malone was evacuated from Gallipoli to Egypt after suffering multiple wounds to his right leg and arm on 1 June 1915. He spent a month in hospital there before being sent to England for further treatment. In January 1916 Terry Malone returned to New Zealand and was discharged from the NZEF in April 1916 as being permanently unfit for further military service. Terry Malone’s wounds left him partially disabled. He received a war pension and he suffered from the long-term effects of his wounds for the rest of his life. He greatly felt the loss of his brother Edmond and later Maurice. Terry Malone died in Wellington on 15 February 1963.58

Malone’s youngest son from his first marriage, Maurice Patrick ‘Mot’ Malone, enlisted in the NZEF in April 1915. A few days after his father’s death, Maurice sailed for Egypt as a reinforcement for the Wellington Mounted Rifles. He served with this unit in Egypt, before transferring, in July 1916, to the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade’s Machine Gun Squadron. On 14 November 1917, Maurice, who was by this time a sergeant, showed great initiative and courage during the New Zealand brigade’s brilliant action at Ayun Kara, near Jaffa. After his commanding officer was wounded, Maurice took charge of his section of machine guns and showed inspiring leadership, particularly when his position was nearly overrun by a Turkish counter-attack. During this action, Maurice shot several of the leading Turks with his revolver and his bold action inspired his men. For his bravery and outstanding leadership at Ayun Kara, he was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal. Late in November, Maurice was wounded in the foot, and after months of medical treatment was invalided back to New Zealand in August 1918. After further medical treatment, he was discharged from the NZEF on 8 January 1919, but continued to suffer from the effects of his wound.59 Following his discharge, Maurice purchased, after being successful in a ballot, a small farm in the Ardkeen settlement for returned soldiers, near Wairoa. He died in Hastings on 16 January 1926 from an accidental overdose of an ointment containing morphia and belladonna, which he was taking to relieve the pain caused by piles. He left a widow and three-year-old daughter.60

Denis George Withers Malone worked for the National Bank of New Zealand in London and later joined the prison service. He was the assistant commissioner of prisons in Kenya during the Mau Mau insurgency, and later the Director of Prisons in Cyprus at the time of the EOKA terrorist campaign against British rule. Between 1960 and 1966 Denis Malone was a reforming governor of Dartmoor Prison. He then retired to New Zealand, living in Kerikeri until his death in 1983.61

Malone’s youngest son, William Bernard Malone, who was always known in the family as Barney, also remained in the United Kingdom after his father’s death. In 1930 he joined the British prison service and began to work in Borstals. Barney Malone quickly demonstrated an impressive mix of determination, intelligence, leadership and innovative thinking. During his time as second-in-command of the North Sea Camp near Boston he instigated a number of educational and other initiatives designed to improve the outlook for the youths sent to the institution. He more closely resembled his father than any of William Malone’s other sons, and was, as a man who knew him wrote, ‘marked out for death or glory’. Barney Malone had an ‘ardent admiration for his father’ and ‘read and re-read’ William Malone’s war diaries. After war broke out in 1939 he was determined to serve and successfully petitioned for release from the prison service.62 He was commissioned in the Scots Guards. In 1941 Barney was one of a group of Guards officers specially selected to watch over Rudolf Hess, at Camp Z, the secret prison, established to hold the Nazi leader. Captain Barney Malone was killed in action at Cassino in Italy on 7 December 1943.63

Rory Patrick Malone, Terry Malone’s great-grandson, continued the family tradition of military service when he enlisted in the New Zealand Territorial Force in 2002. Three years later he transferred to the Regular Force. He was an Wellington (now in ATL) exceptional soldier, heading his initial training course and being the top graduate on his infantry training course. Later after joining 2/1 Battalion of the Royal New Zealand Infantry Regiment as a rifleman he won the Top Soldier Competition. Rory Malone was intensely proud of his family’s record of military service, although he rarely spoke about it. He was a popular, determined soldier who thoroughly enjoyed life in the Army. In 2006 and 2007 Rory Malone was deployed to East Timor. In 2012 he was posted to Afghanistan where as a Lance Corporal he served with Kiwi Company, an element of the New Zealand Provincial Reconstruction Team in Bamiyan Province. During the morning of 4 August 2012, Afghan National Directorate of Security personnel who had gone to the village of Dahane Baghak to detain suspected insurgents came under attack and suffered a number of casualties. Elements of Kiwi Company were dispatched to the scene to assist the Afghan forces. Early in the afternoon the Afghan and New Zealand forces came under fierce attack. Rory Malone was killed after bravely dragging his seriously wounded commanding officer behind cover.64

Malone’s Reputation and Legacy

A great deal has been, and continues to be, written about the Gallipoli campaign. The campaign continues to attract particular attention in Australia and to a slightly lesser extent in New Zealand. Malone has perhaps attracted more attention than any other battalion or regimental commander at Gallipoli. There are, for example, references to Malone on 45 pages of Bloody Gallipoli: The New Zealanders’ Story by Richard Stowers, whereas Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Bauchop, the outstanding commander of the Otago Mounted Rifles, who was also killed in the August offensive, is mentioned on only five pages.65 This can be attributed to a number of factors: firstly, Malone’s strong personality and charismatic and idiosyncratic leadership of his battalion; secondly, the survival of his detailed, revealing diary and extensive collection of letters; and thirdly, to Malone and his battalion’s involvement in three crucial actions during the campaign. These were securing Walker’s Ridge and Russell’s Top (the highest point on the ridge) during the opening days of a campaign, the transformation of Quinn’s Post into a secure stronghold, and finally, and most importantly, the capture of Chunuk Bair in August 1915.

The desperate fighting by the Anzacs to seize and hold Walker’s Ridge and Russell’s Top between 25 and 28 April was absolutely vital to ensuring the security of the foothold gained by the Allied forces at Anzac Cove, and its importance was recognised at the time.66 Lieutenant-Colonel Braund has been widely praised for organising and leading the defence of this vital area. The contribution made to the successful action by the Wellington Infantry Battalion and Malone is noted in the first volume of Bean’s Australian official history,67 and in the first volume of the British official history by C.F. Aspinall-Oglander.68 Later, in 1936, after he had read Malone’s account of the action, Aspinall-Oglander told Barney Malone that in his praise of Braund ‘he had backed the wrong horse’.69 Malone’s strong criticisms of Braund and his men have generally been seen as being unduly harsh, although understandable given the circumstances.70 In his recent well-researched and insightful account of the initial operations at Gallipoli, Chris Roberts has gone further and suggested that Malone’s criticisms were ‘unjustified, churlish and based on ignorance of the situation; the men who fought with Braund paid tribute to his courage and leadership.’71 That Malone spoke to Braund and went up Walker’s Ridge during the fighting points to him having a good knowledge of the situation there. It is also significant that Jesse Wallingford, who was in the thick of the action on Walker’s Ridge is, if anything, more critical of Braund. Malone’s allegation that Braund’s tactics were not driven by the situation on the ground, but by a breakdown in discipline amongst his men due to inadequate training and leadership, is of particular interest.72 There is evidence that discipline amongst Braund’s men did falter, which should come as no surprise given that they were raw troops engaged in combat for the first time under the most trying of circumstances. It must, however, be admitted that Malone landed at Gallipoli prepared to think the worst of the Australians and his experiences on the peninsula did not substantially alter this negative opinion of them.73

Malone was quite properly very proud of the magnificent discipline and spirit shown by his battalion in the Second Battle of Krithia. He quickly realised, however, that the Wellington Battalion and the rest of the New Zealand Infantry Brigade had suffered terribly for no good reason in a botched attack that had no prospect of success.74

Malone was an outstanding commander whose superior organisational abilities and practical, determined approach to problems suited him particularly well for the task of completely reorganising the defences and tactics employed at Quinn’s Post.75 Waite’s The New Zealanders at Gallipoli and Bean’s encyclopaedic Australian official history both describe Malone’s achievements, but provide little detail.76 Peter Stanley’s book, Quinn’s Post: Anzac, Gallipoli details the work Malone and the New Zealanders and Australians who served under him at this vital point, and gives their efforts the prominence they deserve.77

For many years the controversy about the siting of the trenches on Chunuk Bair and to a lesser extent Malone’s role in the decision to consolidate on the Apex rather than press on with an attack on 7 August overshadowed the achievements of the Wellington Battalion and its commander in the breakout from Anzac. These criticisms angered the Malone family and others closely associated with William Malone.78 It was only with the publication of Robert Rhodes James’ first-rate history of the campaign in 1965 that the inaccurate claims about the siting of the trenches on Chunuk Bair, which had been repeated in books by Sir Ian Hamilton and others, were effectively rebutted in a book published outside New Zealand.79 Denis Malone gave Rhodes James access to his father’s diaries, which Rhodes James recognised as being an important source. Major Sir Edward Harston also assisted Rhodes James in his research and was ‘delighted’ with the way in which the book corrected ‘the stupid and inaccurate description which had been repeated at various times about how Chunuk Bair was held and what happened there.’80 In New Zealand, the situation was somewhat different. Waite’s official New Zealand history, which was published in 1919, contains a detailed defence of the siting of the trenches on Chunuk Bair, which concludes: ‘The fact remains that the trenches on Chunuk Bair were the only possible ones for such a situation ... what was done on Chunuk Bair could not have been done any better by anybody else; and there, for the present, the matter must stand.’81 The Wellington Regiment official history that appeared nine years later contains an essentially accurate account of the dispositions and actions of the battalion at Chunuk Bair.82

In the 1980s there was a resurgence of interest in the Gallipoli campaign in general and in Malone and the struggle for Chunuk Bair in particular. This process effectively got underway with Maurice Shadbolt’s 1982 play Once on Chunuk Bair, which was later adapted for the screen. Shadbolt was prompted to write the play by ‘an emotionally numbing visit to Anzac Cove and Chunuk Bair’.83 Once on Chunuk Bair is a work of literature that does not adhere rigidly to the historical facts. In the play Malone is renamed Connolly. Shadbolt did this because of the angry reaction by members of the Malone family to his brief, inaccurate and unflattering portrayal of Malone in his 1980 novel, The Lovelock Version.84 It was not, however, until the publication of Christopher Pugsley’s influential Gallipoli: The New Zealand Story in 1984 that Malone’s actions on Chunuk Bair and the reasons for them became well known in New Zealand. Pugsley’s book was produced in conjunction with an award-winning television documentary. Ted Malone greatly assisted Pugsley’s research by providing him with access to William Malone’s diaries, letters and associated papers.85 Ted Malone was also one of the editors of the 1988 book, The Great Adventure: New Zealand soldiers describe the First World War, which included substantial extracts from William Malone’s diary.86

Although there was an increasing interest in William Malone at this time, Ted Malone’s efforts shortly before his death to interest an Australian publisher in producing an edition of his grandfather’s diary were unsuccessful. The reader contracted by the publisher to review the manuscript considered that the diary was of limited interest, and found Malone to be ‘narrow, fastidious, and irritating’.87 This reader’s report is rather unbalanced, but without reading his letters, especially those to Ida, it is not possible to get a good appreciation of all the aspects of Malone’s character. When the full range of Malone’s writings are examined, a much clearer and well-rounded picture of this complex man emerges.

Malone’s Gallipoli diaries and letters have, especially since the 1980s, featured in discussions about the development of an appreciation of what it is to be a New Zealander. Malone’s many references to his growing sense of national identity and pride have struck a receptive chord with an increasing number of New Zealanders.88 Other aspects of Malone’s thinking and writing, however, sit less well with New Zealanders of the twenty-first century because he was very much a man of his time. Malone was a firm believer in the concept of an heroic death in pursuit of a just cause, which had such a hold on men of his generation and background. The title of this book, No Better Death, is taken from comments made by Malone in his diary on 5 June 1915 about the death of a ‘splendid young fellow’.89 He was a great admirer of Ruskin and marked in a copy of The Crown of Wild Olive he gave to Godley the following passage:

Although he was increasingly aware of the grim realities of war, Malone rather enjoyed the challenges of active service, writing in his diary as late as 4 August 1915 that ‘the prospect of action is inspiriting’.

In the years preceding the 90th anniversary of Malone’s death there was a campaign for him to receive some form of posthumous official recognition. In 2005 the anniversary of Malone’s death was marked by a range of events that were attended by members of the Malone family from both New Zealand and the United Kingdom. In Wellington the Prime Minister unveiled a commemorative plaque in Parliament, a wreath-laying was held at the Wellington Cathedral of St Paul and the first edition of this book was launched.91 Interest in the battle for Chunuk Bair and Malone remains strong in New Zealand.92 Malone has always figured prominently in Taranaki’s memory of the Great War, and each year on 8 August a ceremony is held at the Malone Gates in Stratford to commemorate a man who is now recognised as a national hero.93

William George Malone has no known grave and is commemorated along with more than 300 of his men on the New Zealand Memorial to the Missing on Chunuk Bair.94 He, however, as General Sir Alexander Godley wrote, ‘died at the head of the men who loved him well – a Happy Warrior – a glory to New Zealand and a shining light and example to the youth of the Dominion for all time.’95