CHAPTER 31

WITH CAESAR TALKING, PIECES OF THE BOLO DOVISHAW MURDER puzzle were fast falling into place. DiPaolo knew there would be only a short window of opportunity to get the key players to roll over on each other. He also knew he needed to move speedily, but without upsetting what was now in place with Caesar Montevecchio and several others.

DiPaolo thought back a few months to February, 1987, when he made that arduous drive from Erie to Milan, Michigan, to meet with William “Billy” Bourjaily at the federal penitentiary there. The Michigan prison systems, both state and federal, were now almost as familiar to DiPaolo as Pennsylvania’s wide-spread Department of Corrections.

When DiPaolo introduced himself to Bourjaily, Billy only smiled and asked, “Jesus, Dominick! What took you so damned long to get here?”

DiPaolo didn’t answer, knowing Bourjaily knew how to work the system.

“C’mon, man! I got the word on you. I’ve been waiting.”

DiPaolo suspected Bourjaily had more smarts than Dorler or even Montevecchio. But how smart is someone residing in a federal slammer?

“First, I read you your Miranda rights,” DiPaolo said.

“Dominick. No disrespect man. But I ain’t signing nothing. You came to talk. So, fucking talk to me.”

“How many times have you been to Erie?”

“Erie?” Bourjaily feigned surprise. “Where’s that? Ohio? New York?” Now he was laughing.

“Where your buddy Caesar lives,” DiPaolo reminded him, refusing to even crack a smile. “Sound familiar now?”

“Let me tell you something. I’ve been to Erie a lot. And I know you didn’t come all this way just hoping I’m going to give you something. Besides, I know you probably got the answers to the questions already. Right?”

“Such as?”

“Such as this – if you can get Caesar to roll, then I will roll, too. And you’ll find out just what you want. And, believe me, man, I do know exactly what you want. As I said, you didn’t come up here all this way just to see me because you enjoyed the frigging ride, correct?”

“So, that’s it?” DiPaolo asked.

“Sir, believe me, and again, no disrespect, but that’s all I’m saying. If I keep talking, you are going to put me in a jackpot (street talk meaning compromising position that could nail him for a crime). And I just can’t let that happen.”

That was in February – it was now July – and Caesar was already rolling as the vise tightened!

Shortly after that February chat with Bourjaily, DiPaolo again turned to Robert Dorler. A month after DiPaolo’s eye-opening Michigan meeting with Billy Bourjaily, on March 10, 1987, Dorler was moved from the Rochester, Minnesota, federal penitentiary to Pittsburgh, and then to North Huntingdon, just east of Pittsburgh. The large North Huntingdon Township municipal government building was the site of Pennsylvania’s fourth statewide grand jury investigating the January 3, 1983, execution-style murder of Erie bookie Frank “Bolo” Dovishaw.

It was almost strange to see so many of northwestern Pennsylvania’s law enforcement professionals, lawyers and wise guys all gathered in one place, but some 140 miles from home. Dorler had previously agreed to testify under a grant of immunity from prosecution for any crime he committed in Erie, with the exception of homicide. That meant that no matter what he said about any crime he committed in Erie, he could not be charged or prosecuted for it. The only exception was murder.

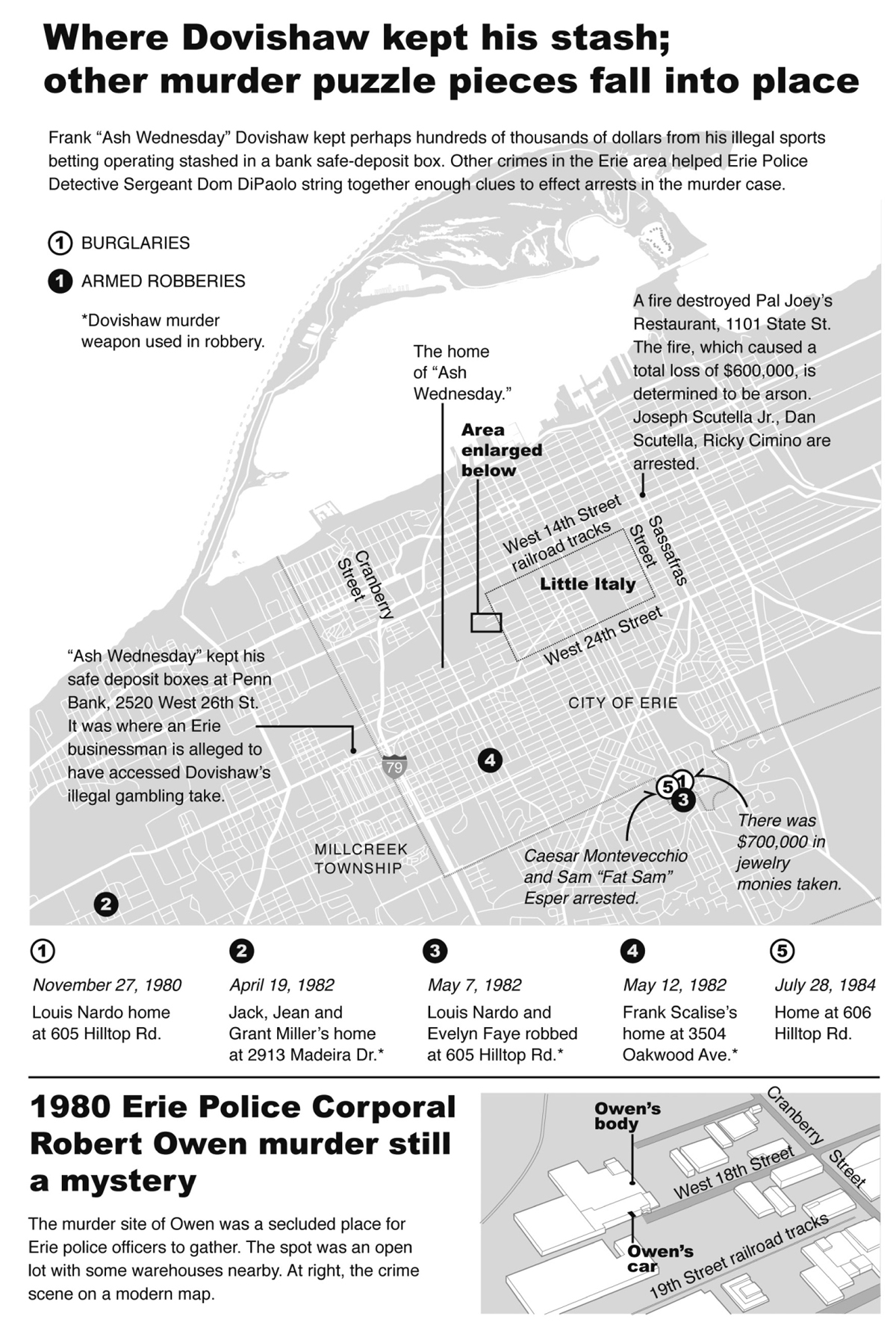

Earlier, Dorler had told state prosecutor Dennis Pfannenschmidt about each Erie crime in which he was a participant. Burglaries, robberies, drug deals. He provided the prosecuting attorney with multiple names, places and details of the crimes. Included were the names of other key participants in the crime spree: Louie Raffa, George Meeks, Fat Sam Esper. Without hesitation, Dorler gave up all his Erie partners in crime.

As part of the deal with prosecutor Pfannenschmidt, Dorler was expected to now do the same before the statewide investigative grand jury. Everyone in law enforcement knows grand jury testimony is secret. At least, such testimony is supposed to be kept secret. Yet, it was later publicly reported that Robert Dorler spent more than four hours on the witness stand before finally being asked by Pfannenschmidt, “What do you know about the Dovishaw murder?”

At the time it was reported that Dorler, somewhat rattled with the question, simply replied, “I refuse to answer that question on the grounds that it might tend to incriminate me. So, I’m taking the Fifth.” If those public media reports of this segment of Dorler’s grand jury testimony were true, it meant Dorler had unwittingly given up the Dovishaw murder. If true, it meant DiPaolo had perfectly maneuvered Dorler into an inescapable corner months before Caesar’s confession!

DiPaolo thought about the message Dorler was sending, intentionally or unintentionally. He was refusing to testify against Montevecchio about a crime he had previously denied having knowledge of, yet he had availed himself of his Constitutional right to evoke the Fifth Amendment against self-incrimination in connection with that very crime.

During every previous conversation between DiPaolo and Dorler, the career criminal insisted he knew nothing about the Dovishaw killing. So why not tell that to the grand jury? Like TV’s famous Sergeant Schultz? I know nothing! But if true, Dorler had – by “taking the Fifth” – unintentionally acknowledged he either played a role in Bolo Dovishaw’s murder, or at least had important information about it.

Immediately following his testimony and once outside the grand jury room, Dorler angrily accused DiPaolo, “You fuckin’ tricked me!”

“No homicides?” DiPaolo blamed the question on a prosecutorial mistake. “Geez, he wasn’t supposed to bring it up,” the Erie cop innocently said.

“Fuck you!” Dorler shouted. “Now I don’t talk on Caesar. How do you like that!”

It was more than an implication. And the comment was heard by news reporters in the corridor outside the courtroom.

With each outburst, it seemed clear to DiPaolo that Dorler was digging a deeper hole. Still fuming, Dorler was taken to his holding cell to await transport back to the Minnesota federal prison. Since the U.S. Marshal Service could not move Dorler back to Minnesota for at least two more days, DiPaolo believed this was another opportunity! DiPaolo drove to the North Huntingdon municipal lockup to tell Dorler of the delay in travel plans.

“You’re fucking with me on purpose because I won’t talk,” Dorler screamed.

But DiPaolo, calmly and truthfully reported, “I have no control over the U.S. Marshals. They operate according to their own schedules. So you’re stuck here.”

It was beginning to look to DiPaolo like fate was sending a perfect hand his way. And now, all he had to do was play it straight, while allowing Dorler to hang himself.

The next morning dawned somewhat reluctantly with murky and gray skies and a chilly mist. March was definitely no paradise in Pennsylvania.

The ringing phone in DiPaolo’s hotel room startled the cop awake. “Jeezus,” he groaned, staring at the night stand clock. It read shortly before 6 a.m. On the phone was Officer Vinnie Lewandowski, who DiPaolo had placed in charge of his transport team. Lewandowski and Officers Bill Leamy and Bob “Goody” Goodwill were moving the key players back and forth between their lock-ups and the grand jury in this western Pennsylvania town. Lewandowski had received a phone call from the North Huntingdon lock-up.

“The guards there say Dorler wants to see you at once, like right now! They say he wants to give up Bolo’s murder,” Lewandowski told DiPaolo. That quickly got DiPaolo’s attention, and he was suddenly alert and wide awake. DiPaolo showered, shaved, dressed and drove the short distance to the North Huntingdon city lockup in minutes.

As soon as he saw DiPaolo, Dorler blurted out: “I’ll tell you what you want, but you gotta put it all together and get me the fuck out of here!”

“I’m listening,” DiPaolo said. “But just start from the beginning. The very beginning. I want to know everything.”

“Look, I have some pretty direct knowledge about the Bolo hit. But I’m not the shooter. And I didn’t arrange it, either.”

“Yeah? So, who was involved?”

“Billy Bourjaily and two other guys. I’ll give you all the details. But I want immunity. For me. And for Billy.”

DiPaolo thought for a moment.

“Was Billy the trigger?” he asked.

“I’m not going to answer that,” Dorler said.

“Well, what the hell!” DiPaolo shot back. “You’ve got to give me a little more than that for me to go to bat for you and Billy on the immunity. You’ve got to know that, right?”

Now it was Robert Dorler’s turn to slowly ponder and consider his next move.

“Okay. The gun used on Bolo was a .32 caliber Beretta. Caesar was the one who supplied it. I know because I got rid of it outside of Pennsylvania in a body of water.”

“Oh?”

Dorler went on to explain that all the weapons used in the armed robberies during 1982 and 1983 were supplied by Caesar Montevecchio.

“What else?” DiPaolo pried further.

“The last thing I tell you is that Bolo’s hit had something to do with bank safe-deposit box keys. But that’s it, DiPaolo! Get me and Billy immunity and then take me back to the fucking grand jury.”

“I need to ask you one thing,” DiPaolo said. “Just what do safe-deposit box keys have to do with all this, with Dovishaw? Tell me that.”

“Should be obvious, for Christsake! Bolo couldn’t be killed until he gave up the fucking keys. And Ferritto – he was supposed to be hit, too. But he wasn’t there. That’s it, man. Right now, I’m done fuckin’ talking.”

It was exactly what DiPaolo needed. The ride from North Huntingdon Township to Erie took less than three hours. But it was well worth it for DiPaolo and every other law enforcement type who labored for so long on the Dovishaw murder case.

At the Pennsylvania Attorney General’s office in the Griswold Plaza, Robert Dorler finally formally gave a statement on Bolo Dovishaw’s murder. He continued to beg off on who the killer actually was, but he sure gave winking and nodding hints it was his pal Bourjaily. What would later (in July) surprise DiPaolo most was how well Dorler’s account (minus the shooter information) would mesh with Caesar Montevecchio’s story. Although some of the minor details given by the two men varied somewhat, Dorler and Montevecchio were remarkably on the same page when it came to outlining key components of the premeditated hit. According to Dorler, Bolo Dovishaw’s key movements had been scoped out for almost an entire week before the January 3, 1983 murder.

“Monday after the New Year’s weekend was picked because of all the bowl games because we knew Bolo would have one of the biggest weekend takes of the year,” Dorler said.

Dorler told DiPaolo the plan was indeed to kill Dovishaw, get his safe deposit box keys and any money stashed in Bolo’s “secret” bathroom hiding place.

“Yeah, and if Ferritto was in the house, there was an extra ten grand for the shooter for hitting him, too. That payoff was supposed to come from Caesar’s coke dealer friend.” Sometime after that, Dorler said the information came to him from Montevecchio that the extra hit money would be paid by Joey Scutella.

He related the events of the night of killing in details as chilling as Erie’s January weather.

“Apparently, from what I was told, the second Bolo answered the door, it was over for him,” Dorler said with a smile. With the 32-caliber pistol (loaded with Norma brand ammunition) held almost touching Bolo’s head, Dorler told of how the shooter forced Dovishaw face down on the floor while patting him down for possible hidden weapons. Still with the cold, .32 caliber pistol touching Dovishaw’s skull, Dorler told of how the killer calmly directed the petrified bookie to the basement and again ordered him face down, this time on the concrete floor.

“He apparently grabbed a couple of belts from some lady’s dresses on a laundry rack and tied up his feet and hands. Bolo was crying and pleading with the shooter, saying things like, ‘Take whatever you want.’ The shooter also asked if Dovishaw had any cash in the house, but Bolo said there wasn’t any. But the shooter knew about Bolo’s secret hiding place in the bathroom and Bolo tells him there’s just a couple of bucks there, that’s all. Caesar told the shooter to get the fucking safe-deposit box keys and the guy says Bolo just gave them up easier than shit. They were, like, in his pants pocket. The guy just took them. Then the shooter has to know where the car keys were and Bolo tells him they’re on a table near the front door. So, that’s it. The guy gets what he wants and then he wastes him.”

“Shit, I need more than that,” DiPaolo said, shaking his head. “A lot more.”

“Okay, okay. If you really got to know!”

“Yeah, I do!”

“Okay. The shooter actually has Bolo get on his knees. He tells him, like Don Corleone, ‘Hey, nothing personal Bolo. It’s just business.’ All the time I hear that he’s still crying his eyes out. Oh, yeah – there was supposed to be this throw rug at the bottom of the steps. So the guy folds it and puts it against Bolo’s head. He puts the .32 right up to the rug, like it was touching it, then shoots the fat fucker just once. Just one time.”

“What did you hear happened then?” DiPaolo asked, emphasizing “hear.”

“Well, fuck, I guess Bolo just dropped like a sack of goddamned potatoes. So the fuckin’ guy gets a sheet from a laundry basket down there and covers him up and puts the rug over him.”

Dorler described how the killer found the bathroom hiding place and pocketed the few thousand Bolo previously had hidden in the vanity. “He went through the rest of the house just to see if there was anything else worthwhile to boost. But I guess there was nothing but the car keys.”

Back in the basement, Dorler continued, the killer pulled the rug and sheet away from Bolo’s body. “What the fuck! He thinks Bolo is alive! Every time before, this guy says, they would shit and piss themselves when they died. But not Bolo.”

No one had come up with this information before, not even Caesar. This obviously wasn’t the killer’s first rodeo, DiPaolo thought.

Dorler told how the shooter described returning to the kitchen and discovering a paring knife in counter drawer, then returned to the basement. “He grabs ‘Ash Wednesday’ by his hair and pulls his head way up, then he just jams the fuckin’ rusty knife into his eye as hard as he could. All the way in. He waits a few minutes and sure enough, Bolo shits and pisses himself. And then the guy knows for sure he was dead.”

Dorler, like others in his underworld circle, knew that “Ash Wednesday” was another of Frank Dovishaw’s nicknames, acquired from his Catholic childhood friends because of the unsightly blemish in the center of his forehead, the place where parish priests apply the ashes from the previous year’s burned palm leaves.

Dorler confirmed to DiPaolo that the initial plan had been for the killer to place Dovishaw’s body in the green Caddy’s trunk. “Fuck, no matter how hard the guy tugs and pulls, he can’t fuckin’ budge the fat fuck. So he’s thinking, Jeezus, what now?”

According to Dorler’s account, before the killer could decide what to do, however, there came a yelling and banging at the front door. The killer couldn’t have known it then, but it was Kenneth Wisinski, father of Dovishaw’s 13-year-old newspaper carrier, Michele, trying again in vain to collect the $21 Bolo owed his daughter. Wisinski perhaps never knew how close he came to sharing the same fate as the man from whom he was attempting to make good on the debt to daughter Michele.

Dorler told DiPaolo the killer pulled out the pistol and waited, prepared to whack whom he believed to be Ferritto or whoever else might try to gain entrance to Bolo’s house. But the crisis quickly passed. “So, the guy waits for a while and when he’s sure that whoever was banging on the door had gone, he goes back downstairs.”

Once again, the shooter attempted to move Dovishaw’s body, Dorler said. And once again, he had no success. “Apparently, there was just no way he was going to get that heavy bastard Bolo upstairs, let alone even budge his body.”

With no curtains or drapes over the basement windows, the killer was concerned the body would be visible to anyone happening to be looking in, Dorler told DiPaolo. “Caesar woulda gone nuts. The last thing any of us wanted was someone peeking in and seeing Bolo’s rotting corpse down there in the cellar. So, the guy covers him up again and then just kicks the knife under the rug. Anyone looking in the windows would only see a big pile of clothes on the basement floor.”

Within minutes, the killer left the now quiet house through the side door and was tooling Dovishaw’s 1979 Deville toward the pre-arranged meeting place – the Station Restaurant at West Gore Road and Washington Avenue, Dorler said. And it was where Caesar Montevecchio soon would be waiting for the shooter, Dorler said, again hinting at Bourjaily.

“I guess there weren’t that many cars there in the back lot that night,” Dorler continued. “But the shooter parks near a few, then pops the trunk. Wanted to check for a bank bag or more. But no such luck. Nothing there but a half-empty case of booze and a couple of empty brown paper sacks.” No one else knew this but the police, DiPaolo thought. Had the killer looked further, he would have discovered more. Much more.

Not very bright, this cold-minded killer, DiPaolo thought with a smile.

Finding nothing in Dovishaw’s car, the slightly disgruntled hit man waited for Caesar Montevecchio to show up at the pre-arranged time of 7 p.m.

“When Caesar gets there, the shooter gives him the bad news about Bolo still being in the basement of the house.”

“So, how did he take it?” DiPaolo asked, already knowing the answer.

“Holy shit! Pissed! Was he ever! But the guy tells him Bolo was just too goddamn heavy to lift. There wasn’t much Caesar could do about it, not then, anyway. Nobody was about to go back there to the house, for Christsakes. It was over and done with and that was that. He just needed to move forward from there. What the fuck, it wasn’t the end of the world, just the end of Bolo.”

“What about the bank box keys?” That was the motive, after all.

“Oh, yeah. Almost forgot! The guy gives Caesar the bank keys. Then Caesar says he’ll call the guy the next day about his payday. I guess that was about it.”

DiPaolo tried to imagine all the chaos that getting rid of the car would have entailed for Caesar and the killer.

“So they take off and dump Bolo’s Caddy at the Holiday Inn on Interstate 90. It’s off the eastbound lanes. With Bolo’s car stashed there, the shooter heads back west toward Cleveland, fast, but within the speed limit. Despite the change in plans with the body and everything, what the hell, they still felt things seemed to be going okay.”

(To make his version sound plausible, Dorler said he was with Caesar at the time, while the shooter had his car stashed at the Station Restaurant. The shooter arrived at the Station in Bolo’s car, then drove it to the Holiday Inn South, with Dorler following him there in the shooter’s car. Once Bolo’s car was dumped there, the shooter drove his own car, with Dorler aboard, back to Cleveland.)

“I mean, he nailed Bolo. Got the damned bank box keys for Caesar. And the shooter even collected a few grand more from the bathroom hiding place. Everyone had been hoping there would be more in the car. But all in all, still not a bad fucking night. The big thing was not to get pulled over heading back to Ohio.”

A good night, DiPaolo thought, following Dorler’s warped sense of accomplishment. “Anything I need to know about your trip back to Ohio?”

“Oh, yeah. That’s when the .32 Berretta was ditched!”

“Where?” This was turning out better than expected.

“In Ohio. I told you.”

But now DiPaolo was starting to get pissed. “Don’t fuck with me Dorler. Just give it to me straight, and with all the details.”

On their way back to Cleveland, Robert Dorler said he and the shooter didn’t go straight home. They took a short detour. About 15 miles after crossing from Pennsylvania into Ohio, Dorler said, as they approached the Youngstown exit, Dorler instructed the shooter, “Get off here. Take Route 11.”

It was the road heading somewhat southwest through Mahoning County, infamous for its reputation as a hotbed for organized crime in the Youngstown-Warren-Niles region that sat nicely midway between Cleveland, Buffalo and Pittsburgh, with Erie in the center of the crime triangle.

“Stay on 11 for a while,” Dorler said he ordered the shooter. It took about 40 minutes along the secondary highway before they came to the Meander Lake Bridge just outside of Youngstown. “As we crossed the bridge, I told the shooter to slow down just a bit. I rolled down my window and tossed out the .32 clip first, then the gun. It’s a good place to ditch hot hardware. Shit, I’ve done it many times.”

Dorler told DiPaolo that Lake Meander wasn’t quite frozen over yet and that the murder weapon likely ended up on the bottom with God knows how many other weapons used in scores or even hundreds of illegal activities.

“Then what?” DiPaolo issued his standard prod after Dorler became silent.

“Nothin’ – the shooter just drove me home to Medina and then drove himself home. That’s all.”

Medina, Ohio, is slightly west of Cleveland. As a result, the shooter had to by-pass his own residence, drop off Dorler, then drive back east back to Cleveland. If Dorler was indeed dropping the dime, it was apparently on Billy Bourjaily. It was the end of a busy day, but one that would occupy DiPaolo’s time and attention for years to come.

So far, Robert Dorler’s rambling story was pretty much following the same course and story lines as Caesar Montevecchio’s account of the night Frank “Bolo” Dovishaw was murdered. DiPaolo knew it was important that while their recollections of that night didn’t need to coincide perfectly, they must be on the same page, especially with the important details of how the killing went down. DiPaolo envisioned defense attorneys like that Lenny Ambrose, delighting in poking holes in the prosecution’s case and tripping up witnesses. So far, so good, DiPaolo thought as Dorler continued to give up himself and his buddies.

Dorler said that the next day, January 4, 1983, Caesar telephoned him and they agreed to meet at 7 p.m. at that same Interstate 90 intersection – Exit 34-Warren – where Dorler and the shooter had taken their gun-ditching detour. They would meet at Mr. C’s Pancake House, a busy place for truckers and travelers alike.

“Caesar was right on time. And he was alone.”

“Were you alone, too?” DiPaolo asked, knowing that Dorler had company.

“No, I got there with the shooter a few minutes earlier just to scope out the joint and make sure there was no set-up, if you know what I mean. Not that I thought there would be. Just being careful, y’know?”

Dorler said the shooter got into Montevecchio’s car and was immediately handed a brown paper bag stuffed with cash. The exchange, he said, only took a few minutes. Dorler said Montevecchio headed back to Erie, while Dorler and the shooter were quickly driving toward Cleveland on the familiar Interstate 90. This time, there were no detours.

But there was a missing detail, DiPaolo recalled. Dorler didn’t mention the part about the argument with Montevecchio over taking the bank safe-deposit box keys back to Bolo’s car at the Holiday Inn near Erie. Yet, he was content to let it slide for now, taking note of the discrepancy between Dorler’s and Montevecchio’s accounts.

In the car, Dorler said, the shooter counted the money in the brown paper bag. “Exactly twenty grand,” he said. “Just what they agreed on. So the shooter counted out fifteen thousand for himself and then gave me five grand for the rides.”

“That was generous of him,” DiPaolo said. “Anything more to add, or is that pretty much what happened and the way everything went down?”

“That’s about it as I remember that night. Y’know, it was a while ago, but you got all the important stuff. Our plan was to just lay low for a few months. You know, no phone calls. No contact at all. It seemed like a good plan.”

While Dorler made his new revelations in March, by July DiPaolo – thanks to Caesar – knew exactly who the shooter was. Dorler had confirmed the entire story. But he substituted Bourjaily for himself as the shooter.