CHAPTER 53

FOLLOWING THE SPLIT VERDICTS IN THE BOLO DOVISHAW MURDER trials, life in the City of Erie in the northwestern-most corner of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania returned to relative normalcy. That included Detective Sergeant Dominick DiPaolo’s life.

He continued coaching the Sacred Heart boys high school basketball team in the Catholic Youth Organization league. Between football and basketball, he coached for 25 years, along with Wally Coughlin and Rick “Snowy” Herbstritt, in 1991 winning the Pennsylvania C.Y.O. basketball state title with 29-1 record. Father John Detisch, Deacon Craig Heuser, and Sister Nancy Fischer, team spiritual advisors, good naturedly took credit for the championship run! DiPaolo continued to be player/manager of The Sports Page slowpitch team every summer, taking enormous pride that his son, Pat, who started off as the team’s bat boy 17 years earlier, led the team in hitting the last three years the team played together. The highlight of Dominick’s athletic career was playing alongside his son.

The return to normalcy included sweaty summers and snowy, shivery winters. Two seasons, mocking Erie people are fond of saying, winter and road work. For the first time in a quarter century, a new mayor, Erie’s first woman to hold the office. Then, the death of the legendary Lou Tullio. Life and death. Both went on as usual.

Most of the stars of the Dovishaw murder era quickly faded into obscurity behind the steady and daily onslaught of new criminal activity. Street gangs and street crime. “Organized crime” per se, evaporated with the times. The actual headliners of the Dovishaw and other investigations became hazy memories. Their time under the bright lights – Bolo’s, Caesar’s, Ray’s, Cy’s, Ricky’s, Joey’s – their time had passed, only to be replaced by a new generation of criminals. Rookie bank robbers, burglars, home-invaders. But not organized like their predecessors.

With the Dovishaw case in the past, Caesar Montevecchio served a few years in prison, was released, and led a mostly quiet life compared to his once-legendary, incendiary and volatile Dillinger-like past until suffering a debilitating fall down the stairs, a home accident that mostly confined him to his house, just another sick and tired old man with memories of ill-gotten gain, but not glory. Never glory. A life wasted. And now, for the first time in their marriage, Bonnie Montevecchio would always know exactly where to find her once on-the-go, career-criminal husband. DiPaolo often wondered whether Bonnie remembered asking him in 1987 if she and Caesar could trust him. She asked if they would grow old together, or be separated. And now, the answer is evident. DiPaolo did not lie to them.

“Set-up” man Anthony “Cy” Ciotti would live out the rest of his life in a nursing home. At age 86, the convicted drug trafficker, burglar, forger, robber, gambler, among other listings on his five-page rap sheet, was still up to his former life’s ventures. He had been in another nursing home previously, but allegedly was thrown out for having whiskey and wine brought in, then selling it to the home’s residents. Early in 2013, Carol Pella, who DiPaolo credited as being one of Erie’s finest investigative journalists from the 1970s through the 1990s, was suffering from the final stages of Lupus and respiratory failure. Under Hospice care, Pella was admitted to a nursing home. On her first day, still the reporter, she phoned DiPaolo – a longtime friend – saying, “Dominick, this is unbelievable! My room is right across from Cy Ciotti! Can you believe this!” Still mentally sharp although her body was wracked with disease, she recalled that after Ciotti had been convicted of the Record Bar robbery in Erie and was led by cops on a perp walk, he spit at her when she tried to interview him. One day at the nursing home, Pella and Ciotti passed each other in the corridor. She told DiPaolo that Ciotti pointed at her, telling his nurse, “Keep her away from me!” Pella died that March at the age of 62. DiPaolo recalls her famous investigative “I-Team,” as well as her great friendship.

As mentioned earlier, the murderously-motivated Ohioan Robert Dorler served hard time in prison until he died there, alone in his cell, in 2008. For him, there would be no mercy.

Mob killer Ray Ferritto moved to Florida with his wife, Susan DeSantis Ferritto, in hopes of living out his golden years in relative peace. Once there, as though by judicial decree from on high, he was totally and fatally consumed by an insidious cancer. Ferritto perished in a horrible death many believed was too good for the admitted hit man who had plied his craft on innumerable victims, perhaps some as evil as himself, but also those who could be considered innocent.

After three years of being baby-sat by Erie police, on July 8, 1987, “Fat Sam” Esper, who had been kept in various “safe house” apartments and hotels throughout Erie County, was finally accepted into the Federal Witness Protection Program. It was that date in 1987 when Dominick DiPaolo and U.S. Attorney Don Lewis drove Fat Sam to meet U.S. Marshals, who took him to a secret destination to spend the rest of his life. DiPaolo thought the drop off/exchange point was almost poetic – it was off Exit 34 off Interstate 90 in Ohio at Mr. C’s Pancake House – the same restaurant where Caesar Montevecchio met Robert Dorler and Billy Bourjaily on January 4, 1983, to pay them for the hit on Bolo Dovishaw.

As life moved on, Arnone’s defense lawyer, Joseph Santaguida continued his successful criminal defense practice in Philadelphia. In May 2011, the Associated Press reported that Santaguida was representing a “Godfather”-like reputed crime boss and mob leader named Joseph “Uncle Joe” Ligambi.

After his trial, Anthony “Niggsy” Arnone returned to his West 18th and Cherry Street food importing business, eventually participating in opening a restaurant across the street in the heart of Erie’s equally legendary “Little Italy.” As life in the slow lane moved on, many forgot about his close brush with the law and the murder accusations against him. After two decades of freedom, Niggsy, like his pals Ray Ferritto and Joey Scutella, died of cancer at the age of 71 on September 1, 2010. His obituary in the Erie newspaper was full of kudos and praise for the man who once had a try-out with the New York Yankees, who passed “after a courageous battle with cancer.” Obituaries in Erie’s newspaper were not news stories, but paid ads. Yet, when DiPaolo got the news of Arnone’s death, he called a confidante and left this short voice mail message: “Niggsy is with Bolo. Do you think they’re in the same barbute game?”

Meanwhile, Theresa Mastrey was fired by PennBank for her conduct as assistant manager – hiding almost $40,000 in cash for her cousin in her own safe-deposit box. The money, it was determined, came from illegal gambling proceeds. She had also admitted forging the name of a notary public while working for PennBank.

She later filed a civil lawsuit against the bank to get back her job along with two years’ back-pay. During the jury trial, under cross examination by the bank’s lawyer, Attorney Roger Taft, Mastrey said the testimony about the illegal gambling money in her safe-deposit box came from other witnesses in the Arnone trial.

DiPaolo testified for the bank about the Dovishaw investigation, Arnone’s and Mastrey’s safe-deposit boxes, including the contents. He told Taft during a trial recess that Mastrey must have forgotten about her Aunt Amelia “Maya” Giamanco, her two daughters, Theresa “Tree” Giamanco-Altadonna Miller, Roseann “Roe” Giamanco-Altadonna DelSandro, and Roseann’s husband, David DelSandro. All were arrested for booking illegal numbers for Big Al DelSandro, who Mastrey said was the source of the money. When the trial resumed, Mastrey testified that it was Attorney Ebert who had made the comment about the notary forgery during the Arnone trial; she had only agreed to it.

The jury returned immediately with a verdict for the bank. There was no appeal. DiPaolo thought those jurors saw her in a different light than the Arnone panel.

Later, Cousin Roseann petitioned the court to get back her $40,000 and two silver wedding bands. But prior to the hearing, an agreement was reached between the parties: The rings were returned to Roseann. The state kept the loot.

Other Erie crime figures and cops also faded away with the passage of time. They were replaced by a new breed and generation of even more un-organized criminals, along with cops who knew precious little about Erie’s previous ruling underworld leaders. In a phrase, the “institutional memory” of the law enforcement branch of Erie government had evaporated – gone were such post World War II law enforcement mob experts such as Eddie Allen, Jim Kinnane, Frankie Schwartz and several others who started their careers in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s.

DiPaolo, was one of the few left who knew of the past and how it related to the present. For example, several months after Niggsy passed, an Erie police leader phoned District Court Judge DiPaolo to ask, “Dominick, I know I sound pretty dumb, but can you please tell me whether the Dovishaw case is still open? The FBI just called to ask whether the case is open, and, hell, I couldn’t even tell them.”

“No,” DiPaolo told one of Erie’s top cops. “No, that case was closed years ago.” And then DiPaolo thought, imagine that, the FBI not knowing what’s going on! Yet today’s crime-fighting police officers, if ignorant about the subtleties of Erie’s long and storied and almost rich underworld past, at least do know something about street crime, gangs and the brand-new cyber offenses.

DiPaolo continued with the Erie Police Department, still handling most major crimes as they were committed and reported, and still specialized in homicides. He also became a training officer for rookie detectives. Some made it; some didn’t. One of his trainees, Frank Kwitowski, would later become captain and the head of the Detective Division. DiPaolo headed four more homicide investigations and was again successful with guilty verdicts returned, including life in prison for two men, in the cases that went before juries.

The last homicide DiPaolo investigated was the beating death of 44-year-old James “Shorty” Stanley, who had been left for dead in an alley behind the boarding house where he resided. Stanley and his friend, Allen Garfield, 41, were beaten by Anthony Paolello, 45, after a woman who had been raped by Paolello in another room of the boarding house ran to Stanley’s and Garfield’s room for help. Paolello, along with Daniel Funt, 20, who also lived there, and Anthony DeFranco, 28, known as “Tone Capone,” beat the two men because of the possibility they would report the rape to police. The assailants also took $70 from Stanley. Garfield made it to a nearby bar before he passed out. Bar patrons called for an ambulance, which apparently saved his life. After 20 days in intensive care, Garfield was well enough to tell DiPaolo and his partner, Detective Gerald McShane, who had beat them.

Paolello was found guilty of first degree murder and sentenced to death, the penalty later revoked and converted to life without parole. Funt got up to 55 years for third degree murder and robbery. Tone Capone was offered a plea deal to third degree murder. In return, he would have gotten 20 years in prison. But Attorney William Weichler, Attorney Ambrose’s law partner, turned down the plea offer. His client was convicted of second degree murder. Leaving the courtroom, the defendant sneered at DiPaolo. Capone was sentenced to life in prison with no parole. He rolled the dice and got snake eyes, DiPaolo later said, also recalling he had been the guy who was proud to say Caesar Montevecchio was his idol.

But DiPaolo’s time as a cop also began running short – this of his own choosing. As much as he relished locking up the bad guys, he had been interested in politics for many years. He managed to craft and hone that interest into an art form. Some of it was in his genes, passed on by his dad, a popular west Erie ward healer. For DiPaolo, Erie’s Sixth Ward politics represented a love and a fascination. But wherever his interest originated, it was more than a passing fancy. He was an elected committeeman, and Sixth Ward Democratic Chairman for 14 years.

By 1993, just four years after the Arnone murder trial ended in an acquittal, the political bug finally bit into the Erie cop – and hard. With all the confidence of a rookie politico, but a confidence bolstered by his “Inside Baseball” knowledge of Erie’s stormy political scene, DiPaolo tossed his hat into the five-candidate race for district judge in the huge and politically motivated Sixth Ward – one of the City of Erie’s largest political subdivisions. It was a major decision, running for public office, as DiPaolo had to take a leave of absence from the Erie Police Department. It meant no pay. No health care insurance. With two kids in college, a mortgage and car payments, DiPaolo had to hope and pray what he was doing was right. But in politics, it’s all about the timing and DiPaolo had no doubts the time for him to run for office was right. After a few loans, much breath-holding and a tough four months, the DiPaolo family got through the campaign.

Of the five candidates in that 1993 election for Sixth Ward District Judge, DiPaolo easily won both the Democratic and Republican nominations, demolishing the field, including the sitting incumbent district judge.

Dr. David Kozak, Professor of Public Policy at Gannon University, a presidential scholar and perhaps Erie’s foremost political observer and commentator, told DiPaolo after that primary election that he considered it “amazing” DiPaolo pulled the number of votes he did in a five-person race, especially since it was suspected a large number of Italian families in the Sixth Ward were working against him – Arnone, DiNicola, Scutella, Cimino, Calabrese, Mastrostefano, Ciotti, Serafini and Giamanco-Altadonna, to name a few – all those he had dealt with during his police career.

The Friday night before the May primary election, DiPaolo and a group of his volunteers ended up at The Sports Page for pizza and suds after campaigning all evening. Before long, exhausted Dom and his wife, Janet, bid goodnight to the volunteers and left for home. A short time later, son Patrick, then studying at Thiel College, arrived in town with his buddies to help with the final days of his dad’s campaign. Also helping out was the DiPaolo’s college student daughter, Dawn, who was home with her friends to campaign for Dom. Both DiPaolo kids had gone directly to the “The Page,” hoping to surprise their parents, only to learn from part-owner Rich Carideo that the DiPaolos left minutes earlier.

As the entire group enjoyed beer while waiting for their pizza, a young woman approached Pat DiPaolo and asked, “Are you Dom DiPaolo’s son?” When Pat responded in the affirmative, the woman spit in the young man’s face, then walked away. The rest of the group, stunned, could only stare in disbelief. Pat, meanwhile, went to the men’s room, where Carideo brought him a fresh towel and apologized for the incident. Daughter Dawn, and her friends Kara Schlosser, Jenny Kupczyk and Renee DeRose, wanted to approach the offending woman, but Pat would not hear of it and directed the group to leave. Several days later, Carideo told DiPaolo how impressed the others were with Pat’s actions, with all knowing that just four days before the election the woman wanted to provoke an incident. Only later, DiPaolo said, did he learn the woman was Kelli Scutella, daughter of Joe Scutella. DiPaolo said she was working on the committee of the incumbent that DiPaolo that was running against. But in the end, it was DiPaolo who enjoyed the satisfaction of winning on election night. Years later, Rich Carideo and Peter Pallotto still talk about the pre-election incident at The Page, and about how Pat, who starred in football, wrestling and baseball in college, walked away from a potentially explosive and embarrassing situation that could have harmed his dad’s chances in the election. The DiPaolo kids, unlike some families at the time, others said, had values and respect.

And so it was in January 1994, after 25 years of exemplary service with the Erie Police Department, Det. Sgt. DiPaolo became District Court Judge DiPaolo and a leading member of Pennsylvania’s minor judiciary.

Before DiPaolo left the service of the City of Erie, he was honored by Erie City Council as the most decorated police officer in Erie’s 200-year history. The citation pointed out that DiPaolo was not only the recipient of the “Policeman of the Year Award,” but also the Erie County Bar Association’s prestigious “Liberty Bell Award,” the Erie Insurance Club’s “Dedicated Public Service Award,” and Mercyhurst College’s coveted “James Kinnane Law Enforcement Award,” named to honor Erie’s long-serving Federal Bureau of Investigation Special Agent in Charge. Among many honors, DiPaolo was inducted into the National Police Hall of Fame in Miami, Florida. During a quarter-century police career, he had amassed 2,006 criminal arrests. He investigated 32 murders. Many of those murder defendants are still serving life terms.

DiPaolo had also been successful in 185 jury trials that ended with convictions, as well as seemingly countless cases that culminated with the defendants understanding the hopelessness of their situations and pleading guilty. Hearing the word “guilty” from the jury had always provided DiPaolo with a motivating rush. In his entire career, only two homicide cases had culminated with acquittals by juries.

The Niggsy Arnone acquittal was a bitter pill to swallow. A stinging loss after such a long and meticulous investigation that spanned the better part of the eastern United States.

The other acquittal involved Louis DiNicola, a roofer who in 1979 was charged with torching a house in Erie’s Little Italy. The motive for the fire allegedly was that a woman who lived in the home had spurned the defendant’s affections. The woman’s two small children and an adult man who lived elsewhere in the two-apartment house had died in the resultant inferno that swept through the structure.

DiPaolo and Detective Donald Gunter later arrested DiNicola, charging him with one count of arson and three counts of homicide.

Attorney Bernard Siegel, a former Erie County First Assistant DA, was brought into the case as a special prosecutor after the Erie County District Attorney’s office recused itself from participating in the prosecution. The recusal reportedly occurred because in 1979, then Assistant District Attorney Tom Ridge, spoke about the case to Ron DiNicola, brother of the defendant, while Ron was a student at Harvard, Ridge’s alma mater. Because of the perception of a possible conflict, Attorney Siegel was brought in to prosecute.

Despite the almost entirely circumstantial evidence presented by Special Prosecutor Bernard Siegel in 1980, the jury panel convicted DiNicola of all the charges that DiPaolo had brought against him. DiNicola was sentenced to serve three life terms, plus another 20 years, in a state penitentiary. The jury had 46 minutes before returning to the courtroom with the stunning guilty verdict.

In 1994, some 15 years after the crime and DiPaolo had ended his police career, DiNicola’s new attorneys won a new trial for their client. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court granted a new trial based upon just one line of improper testimony out of the many hundreds of pages of testimony. The new defense team was headed by DiNicola’s brother, Ron, a prominent lawyer who staunchly defended his client with brotherly motivation and love. Other members of new dream team included former U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clark, former legendary New York City police officer Frank Serpico (portrayed by Al Pacino in a movie of the same name), and Dr. Cyril Wecht, the controversial Allegheny County coroner who helped investigate the deaths of luminaries such as Elvis Presley, Marilyn Monroe, and even President Kennedy. Wecht was indeed the medical examiner for the stars. Several local attorneys were also a part of the defense. The group was considered as much a “dream” legal team then as the lawyers who later represented O.J. Simpson during the former NFL and movie star’s murder trial in Los Angeles.

Dom DiPaolo was standing outside of Erie County Judge Richard Nygaard’s courtroom, waiting for the start of a bond hearing requested by the “Dream Team” when Hyle Richmond, longtime courthouse reporter and evening news anchor for WICU-TV, Erie’s NBC affiliate, stopped to say, “Wow, Dominick! This is a real high show today with all these heavy hitters!” Just then, a man in his early 50s, thin, with a full beard and wearing a suit that appeared two sizes too large and with no tie, asked, “Excuse me, are you Dominick DiPaolo?” When DiPaolo acknowledged that he was, the man extended his hand, saying, “I’m Frank Serpico. Heard a lot about you!”

Slightly stunned, DiPaolo said, “Heard a lot about you, too.”

The men shook hands and after polite small talk, Serpico said, “Hey, nice meeting you.”

“It’s an honor,” DiPaolo said. “Read your book. Saw your movie a few times and I believe you are a very honorable man. I respect you for what you did, and I’m sure that once you get in to this case and determine what really took place, you will be testifying for us.”

Smiling, Serpico said, “I appreciate your kind words and will definitely talk with you later!”

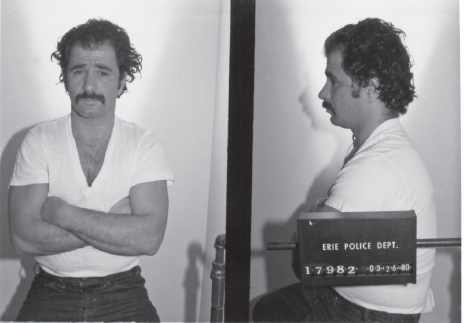

Louis Paul DiNicola was convicted in 1980 on three counts of murder and one count of arson and sentenced to three consecutive life terms. Fifteen years later, he was granted a new trial on appeal and found not guilty. (Courtesy of Erie Police Department)

DiPaolo believed Frank Serpico was in Erie for the media. He did not testify. There was nothing for him to add to the defense. But, by the time the second Louis DiNicola trial began in Erie County Court, one key witness had passed away, and several others had changed their stories. Also, one of the hired defense witnesses in the trial, Dr. Cyril Wecht, established doubt in the minds of the jurors by introducing forensic evidence with which DiPaolo disagreed.

(In 2008, Wecht was indicted in Pittsburgh by overzealous Feds, DiPaolo believes, including U.S. Attorney Mary Beth Buchanan. Wecht was charged with 41 public corruption counts as the government spent over $200,000 to bring him to trial for supposedly improperly using $1,700 in his public position as Allegheny County Coroner. After a federal jury was declared hung, Buchanan announced she would retry Wecht. She assigned Leo Dillon as lead prosecutor for the second trial. Dillon, an Allegheny County assistant district attorney in the early 1980s, had tried Wecht for theft. Wecht was acquitted. As a result of this new trial, however, the U.S. House Judiciary Committee investigated Buchanan and others, as there was new concern about select prosecution in the Wecht case and others. Out of the 365 cases Buchanan prosecuted, 298 were against Democrats and 65 against Republicans. In the Wecht case, she was accused of intimidating former jurors by sending agents to their homes and work places to determine why they did not convict the Democrat. Former Pittsburgh Mayor Tom Murphy said the charges and trial were examples of excessive prosecution by the feds, adding they were driven by ideology rather than truth and justice. Buchanan and Dillon backed off. Wecht was not re-tried on the federal charge. Buchanan resigned in 2009.)

Combined with the high-powered defense team, the death of witnesses, a less-than-supercharged prosecution team that wasn’t the A-Team from the first trial, DiPaolo had an intuition that this case was in jeopardy. It was. At the second DiNicola trial, just as DiPaolo had predicted, 15 years after the fatal fire, DiNicola was acquitted and then ultimately released from his incarceration.

There was one other homicide DiPaolo and Gunter investigated that both hoped would have had a different outcome: On December 10, 1980, Roger Kent Hamilton, 38, a maintenance worker at an Erie McDonald’s, was gunned down while taking out trash at 2 a.m. Later, from the spent casing found at the scene, it was determined Hamilton was shot with a .22 caliber weapon. Sam Covelli, the restaurant’s owner, posted a $25,000 reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the murderer. Several days later, a witness reported Hamilton had argued with another man at the restaurant’s rear door. When the victim fell to the ground, the other person fled. But the witness observed neither a flash from a discharging weapon nor did he hear the gun’s report.

The witness agreed to undergo a polygraph exam and also hypnosis, an investigative tool used at that time. The witness was placed under hypnosis by William Vorsheck of the Erie Institute of Hypnosis, who helped DiPaolo previously and was used in many police investigations. Results from the lie detector and the hypnosis were positive and conclusive.

After identifying the murder suspect as Richard Armstrong, 34, the detectives and Assistant District Attorney Frank Kroto agreed Armstrong would be picked up and a search warrant issued for his apartment. When the officers approached Armstrong, he said of Hamilton, “Fuck him. He had it coming!” Then he lawyered up.

During a photo line-up, three other witnesses identified Armstrong as being at McDonald’s at the time of the murder and Armstrong was charged with the crime.

A short time later, while Millcreek Township Police were investigating an armed robbery and homicide at the Ponderosa Steak House, just west of Erie, 45- and 22-caliber spent shell casings were found at the scene. Mark Taft was shot several times in the back and while he was on the ground. DiPaolo arranged for Pennsylvania State Police ballistics expert Sgt. Virgil “Butch” Jellison to compare the .22 shell from the Hamilton murder with that found at the Taft homicide scene. DiPaolo and Gunter still had serious reservations about the Hamilton murder and wanted all possibilities checked. Jellison had no doubt the .22 shells matched. The charges against Armstrong were dismissed after this new evidence was reported to ADA Kroto.

Through Millcreek Police, John Peter Laskaris was identified as a suspect in the murder, robbery and an attempted bank job, and arrested in West Virginia. Just several years earlier, Laskaris was involved in a homicide investigation surrounding the death of Erie Strong Vincent High School student Debbie Gama, who was killed by her teacher, Raymond Payne. Laskaris agreed to a deal, testifying against Payne. who was convicted and sentenced to life in prison without parole. (In the early 1970s, DiPaolo had received information from Al Bilotti, an Erie school police officer, that Raymond Payne was providing students with marijuana. Police Chief Sam Gemelli advised the school superintendent of what Payne was doing, but Payne denied the accusations and the investigation was dropped. “If we, along with Bilotti, could have continued to investigate Payne, maybe Debbie Gama would still be alive,” DiPaolo later observed.)

In the Hamilton investigation, Millcreek Police Detective Sergeant Richard Nagosky advised DiPaolo that more information could be available from Laskaris and Edward Palmer. DiPaolo and Gunter traveled to Fairmont, West Virginia, where the two were being held on other charges. The detectives learned Laskaris and Palmer had planned to rob McDonald’s the night in question. They had inside information from an employee dating Laskaris that no bank deposits would be made over the weekend and the safe would be stuffed with cash. As the two approached the parking lot, Armstrong and Hamilton were either talking or arguing at the rear door, which Laskaris’ girlfriend left unlocked. Laskaris and Palmer were upset the other two were in their way; one shot was fired from a .22 automatic fitted with a silencer. Hamilton dropped to the ground, Armstrong ran, and Laskaris and Palmer quickly drove away.

A month later, Laskaris, while robbing the Ponderosa, killed Taft. Laskaris was convicted in West Virginia and in Erie on a number of armed robberies, and the Mark Taft murder. Laskaris got life in prison with no parole, plus 60 years. Palmer, who cooperated with authorities, got five years. It appeared that the eye-witness, whose observation originally resulted in the arrest of Richard Armstrong, was correct all along: He saw the argument, then Hamilton go down and Armstrong running away. He did not see Laskaris, or hear the shot because of the silencer. The witness passed both the polygraph and the hypnosis because he had been telling the truth, DiPaolo and Gunter later explained to ADA Kroto. In 1987, District Attorney Veshecco and DiPaolo went at it again when DiPaolo learned Veshecco would not prosecute Laskaris on the Hamilton murder, apparently deciding, to DiPaolo’s dismay, that one life sentence was enough. Meanwhile, Richard Armstrong’s days were numbered. He died following a fall. He had been another of Marjorie Diehl’s lovers.

Even to this day, after DiPaolo won his fourth and possibly final six-year term of office on the bench, the former cop remains philosophical about his only two courtroom losses.

“The juries in the ‘Niggsy’ Arnone and Louie DiNicola cases spoke and I respect their decisions,” DiPaolo easily says without a hint of rancor or bitterness. “Even more, I respect the system that allows juries of one’s peers to function unimpeded in our society. That’s our system. And win or lose, it’s the best system and we live by it. It’s often well-intentioned guesses that the juries render.”

Yet, after some contemplation over the lost murder cases, recalling the grand jury sessions, arraignments, preliminary hearings, trips to Florida, Ohio, West Virginia, Indiana and Michigan, he still manages to add a final thought based on this public servant’s deep religious convictions: “Someday – and that day has already come for Niggsy – I truly believe that each man will have one more jury to face. Let’s see if He believes them.”

That’s Dom DiPaolo. An Erie guy with deep roots in his community.

First a cop. Now a judge. Tough, but fair.

And that’s exactly what his life stands for: Justice for all.