Among the natural rights of the Colonists are these: First, a right to life; secondly, to liberty; thirdly, to property; together with the right to support and defend them in the best manner they can. These are evident branches of, rather than deductions from, the duty of self-preservation, commonly called the first law of nature.

– Samuel Adams

In America, suspects are considered innocent until proven guilty, right?

Wrong.

Consider the case of a Maryland man named Dale Agostini, who was driving with his fiancée; their sixteen-month-old son, Amir; and an employee of Agostini’s restaurant, through East Texas a few years ago, on their way to buy some new equipment for their business. Agostini carried $50,291 in the car – a large sum, but one which he said spoke volumes among restaurant equipment sellers, who would slash prices if the buyer paid in cash.1

The four, all black, were approaching the Texas town of Tenaha, about an hour from Shreveport, Louisiana, when a police officer pulled them over. The road they traveled was a known drug-trafficking route, and the officer made them wait while he sent a drug-sniffing dog to scour their car. The officer then told them the presence of the dog actually served as a warrant, so he could legally search their vehicle. He found the cash, accused them of money laundering, arrested the adults, and sent the infant to child protective services.2 Police also confiscated six cell phones, an iPod, and the car Agostini was driving.3 That was in September 2007.

Agostini was never charged with a crime. But he was finally released, along with his fiancée and employee, was given his child back, and was able to win back his cash – that last only after months of fighting in court to prove he had rightfully earned it through his restaurant business.4

What the heck happened?

Turns out, Agostini was the victim of a long-running police power play to use asset forfeiture laws to seize properties.

In September 2012, the American Civil Liberties Union and an East Texas attorney reached a settlement with Tenaha authorities in a class action suit that revealed Agostini was one of about a thousand black or Hispanic motorists who had been pulled over between 2006 and 2008 in that same Shelby County area, for no apparent reason except for officers to strip them of cash and property. The judge called the police action a classic case of highway robbery, agreeing with plaintiffs that law enforcement had engaged in racial profiling to target their victims.5 But what gave police the right to confiscate the properties of those they pulled over was actually based on Texas law – an asset forfeiture right that lets law enforcement take money and other items from those suspected of engaging in illegal drug-related activity. The police can seize the properties without waiting for a conviction or admission of guilt.

Another caught up in the Tenaha police snare in August 2007 was thirty-two-year-old James Morrow, a black man en route to visit his brother in Houston, pulled over for driving too close to the white line. Morrow didn’t commit any crime; police had no warrant for his arrest. Yet they ordered him out of the car and began interrogating him, demanding he explain why he was driving through the small town. As with Agostini, the police brought out the drug-sniffing dog and searched Morrow’s car. They found, and confiscated, $3,969 in cash and two cell phones. Morrow was never charged with a crime, but was transported to the police department and jailed nonetheless. The district attorney gave him a choice: forfeit the cash to the police or face prosecution for money laundering. Morrow chose the former, but then hired an attorney – for $3,500 – to win back his money. He was left with $400 and an attitude of utter shock. He told the ACLU who fought his case as part of the class suit against Tenaha that he couldn’t believe police could act that way in modern days.6

Once again, blame Texas asset forfeiture laws.

It sounds like a scenario right out of the eighteenth century, when England’s system of “writs of assistance” permitted the king’s soldiers to enter any home and take whatever they determined to be contraband. That untenable situation is what led in part to the American Revolution – but apparently, we have come full circle. The federal and state civil forfeiture laws are exactly what the Founding Fathers feared, which is why they wrote the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution:

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offense to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation. (emphasis added)

The Department of Justice defines its Asset Forfeiture Program as a means of obtaining properties that were used during the commission or facilitation of a federal crime. Its main purpose, the department claims, is to bolster public safety, specifically by taking away the tools criminals use to commit their crimes. For instance, if a drug dealer depends on a vehicle to ply his wares, law enforcement can take away his car and in so doing “disrupt or dismantle” the criminal operation and organization, as the Justice Department puts it.7 The US Marshals Service oversees the program, and is in charge basically of disposing of all the properties seized by law enforcement agents around the nation.8

On the surface the idea seems sound. Why not let law enforcement seize items that criminals use to commit crimes? Certainly, the fear of losing one’s valuables might serve as a deterrent to some criminals, and perhaps public safety really does come out the winner.

The problem, of course, is that the program is rife with abuse. Federal, state, and local law enforcement often use the asset forfeiture power more for personal gain than for genuine protection of the community. It’s common sense, really. Take one small, cash-strapped town with a police force on a tight budget. Then give the police a means of adding to their coffers via on-the-job busts that don’t have to meet high standards of probable cause. The tea leaves aren’t hard to read. As the National Bureau of Economic Research found, when policy gives police the ability to keep what they seize, they seize more, and not always with justification.9

The genesis for this widespread system of abuse was the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970, which was enacted to fight the rising drug-trafficking epidemic and gave federal authorities the power to forfeit properties in drug-related cases. The law allows for criminal asset confiscation, where the property used in a crime could be seized and confiscated only after a criminal was convicted. But federal and state statutes recognize two other types of asset forfeitures too – civil and administrative.10 This is where the standard of conviction falls to the wayside. Police and government agents can seize properties from those suspected of certain crimes without waiting for a guilty plea or verdict, and without having to obtain a court order or warrant.

In 2000, President Clinton signed the Civil Asset Forfeiture Reform Act, aimed at giving victims a few more rights in the fight to regain their seized properties.11 But in the end, the basic gist of the power still stands: civil forfeiture gives police the legal right to seize cash and properties from suspects, while property owners are put in the sticky situation of having to prove their innocence to win back their properties.

Meanwhile, the draw of big money from asset forfeiture is a temptation that’s hard for government to resist. Put bluntly: asset forfeiture is big business.

In 1984, Congress passed the Comprehensive Crime Control Act, which, among other things, created a new Department of Justice Assets Forfeiture Fund. That’s where all the monies from asset forfeitures go, awaiting disbursement and allotment.12

State and local law enforcement agencies share in this pot, thanks to what the federal government created – an Equitable Sharing Program – that lets all the participants of a criminal or civil investigation receive a share of the asset forfeitures.13

For localities with cash flow issues, the Equitable Sharing Program is a budget dream come true. The US Marshals Service reported that between 1985 and 2012 the amount of Equitable Sharing Program proceeds that were distributed among all the players amounted to $5.8 billion. Another $2.4 billion in assets was still in the US Marshals’ coffers, awaiting distribution.14 The Department of Justice figures break it down with more specificity, by state and even jurisdiction.

For instance, during fiscal year 2012, the asset forfeiture program resulted in authorities confiscating a 2008 Viking Sport Fisherman-Cacique vessel valued at nearly $3.1 million from a Bayfield, Wisconsin, owner; $2.9 million in real property in Austin, Texas; $2.7 million in Chinese collectible coins and cash in Chesterfield, Missouri; $2.8 million in silver coins, bars, and scrap metal in Coeur D’Alene, Idaho; $5 million in jewelry in Latrobe, Pennsylvania; a Cessna Citation 93 airplane valued at $1.7 million from Palm Springs, California; more than $25 million in artwork in New York; and 5,540 iPods valued at almost $1.2 million in Miami, Florida.15

That’s just a drop in the bucket for fiscal year 2012 asset forfeitures reported by the Department of Justice. It doesn’t even account for the millions of dollars in cash that agents seized during that twelve-month period. In one particularly lucrative bust, law enforcement netted almost $78 million in cash from a single operation in New York; in another, also in New York, they seized almost $75 million. Agents seized another $54 million in an asset forfeiture in Denver, Colorado.16

Not a bad haul for the civil servant sector.

As you can imagine, a US General Accountability Office investigation found the asset forfeiture program is in need of reform. The GAO reported in July 2012 that annual revenues from the Assets Forfeiture Fund increased significantly between 2003 and 2011, from $500 million to $1.8 billion. Part of the reason was an increase in prosecutions in cases of financial fraud – meaning some of that seized money was due to valid property seizures carried out in line with the full spirit of the law. But the GAO also said that the Department of Justice didn’t properly document how it carried over undisbursed seizure funds into the next budget year, opening the doors to fiscal mismanagement – especially since the funds can be used for any expenses, as long as they relate to agency operations. And, the GAO said, the Department of Justice failed to expressly state how disbursements of seizure dollars are made, and what type of formulas are used to give money to one agency instead of another. In other words, the GAO said that those determination factors could be a lot more consistent and transparent.17

What the GAO report failed to address, however, was the core constitutional concern with the program: how is it legal for government to take private property without just cause?

While many Americans may see the sensibility of criminal asset forfeitures, or those that take place after a suspect has been tried and convicted of an actual crime, it’s distressing that civil asset forfeitures allow for property seizures absent any crime or guilt. Here’s an example of forfeiture law in motion that’s easy to stomach: In December 2013, Virginia attorney general Ken Cuccinelli announced a cash award of $245,000 for a few local police departments in the state to buy bulletproof vests. The money didn’t come from taxpayers, though. It came from asset forfeiture money Virginia earned by serving as a lead investigator in a massive Medicaid fraud case that settled for $1.5 billion. Virginia’s asset forfeiture share from that case? It was $115 million. The $245,000 was one of the first drops in the bucket of asset forfeiture money Cuccinelli promised to share with local and state police agencies.18 That’s a criminal asset forfeiture and subsequent cash disbursement that many would applaud.

But the darker side of these powers completely obliterates any constitutional notion of innocent until proven guilty.

Civil asset forfeiture laws are much more lax and let government entities and their local police partners seize properties – including homes, cars, and cash – without due process of law, without a court guilty verdict or plea, and really, without very much probable cause. In essence, all police need according to the law is a “suspicion of guilt,” and then they can take property.19 Moreover, the third leg of asset forfeitures – the administrative forfeiture – is where law becomes even more loosey-goosey in terms of favoring the police over the individual. Administrative forfeitures give law enforcement officers the right to outright take properties valued below $500,000 based on what the FBI defines as “a reasonable ground for belief of guilt.” As if that weren’t unconstitutional enough, the law allows for an exemption for cash – meaning, police can confiscate any amount of cash at all, as long as they think someone might be breaking a law.20

Innocent? Guilty? With civil forfeitures, that’s a moot point – an unnecessary consideration. And those who want their properties back have an uphill battle. The law puts the onus on those whose properties have been taken to prove their innocence, rather than on the police or government agency to prove their guilt. It’s a topsy-turvy scenario that’s not only difficult for victims to argue and prove in court, but expensive. Fact is, most asset forfeiture laws favor police, not property owners.

Convoluting the issue further is that states are free to determine what standard of proof they will use to carry out an asset forfeiture on a suspect or property owner – and those standards might differ from the standard the federal government uses.

Only a handful of states require police to meet the higher standard of “beyond a reasonable doubt” when faced with a question of asset forfeiture. The federal government and most states use the more relaxed standards – and in most cases, the evidence needed to seize property is actually lower than the proof needed to show that the individual was guilty of any criminal act that allowed for the seizure in the first place.21 What results is that asset forfeitures are carried out with alarming frequency on the truly innocent.

It’s almost as if the government has a license to steal – but sometimes, justice does prevail.

A sixty-nine-year-old man in Tewksbury, Massachusetts, nearly lost his family-owned business, Motel Caswell, after federal prosecutors seized it and claimed it was commonly used to facilitate illegal drug sales. The owner, Russell Caswell, denied that claim but was nonetheless forced to take his fight with federal authorities to court. In January 2013, a judge found in Caswell’s favor, homing in on testimony that showed the motel had actually given police free reign to scope out the property and investigate suspected drug deals – belying any claim from police that motel management tolerated illegal activity and, therefore, facilitated crime. Caswell won his case and won back his motel. But his win is somewhat tempered by this realization: Caswell was forced into a legal brouhaha over his property rights that never should have been waged. He was never even charged with a crime.22

That’s the insidious evil of asset forfeitures, though. And abuses of the power aren’t exactly few and far between.

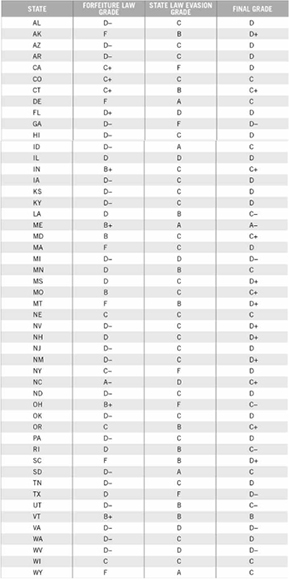

The nonprofit Institute for Justice tracked and graded asset forfeiture trends at the state level and found, with the exception of Maine, North Dakota, and Vermont, all ranked average or subpar in terms of upholding the individual’s constitutional rights versus the ability of police to confiscate. The organization determined rankings based on the percentage of forfeited assets that agencies in the state were allowed to keep and the level of difficulty for property owners to win back their assets. Maine received an A–, and two other states, North Dakota and Vermont, received B+ and B, respectively. Eighteen other states fell in the average and low-average category, the C range. The remaining were rated between D+ and D–, near failing.23

Forfeiture Law Grade: This grade indicates how rewarding and easy civil forfeiture is in a state.

State Law Evasion Grade: This grade indicates the use of equitable sharing as a measure of the extent to which state and local law enforcement agencies attempt to circumvent limits in state law. Higher grades indicate lower levels of equitable sharing.

That’s a dim showing, at best. And it’s led to some egregious police abuses over the years that seem more in line with KGB tactics than American founding law. An elderly couple who had lived in their West Philadelphia home for nearly fifty years were practically tossed into the streets in August 2012 after their son, thirty-one, allegedly bought a small amount of marijuana from undercover police on the front porch of the house.25 After the son was arrested, police told the parents – the mother was sixty-eight and the father, seventy, and in poor health from pancreatic cancer – the state was going to take their home and sell it at auction. The proceeds would be split between the district attorney’s office and the local police department. Here’s the real kicker: The asset seizure was due to go forth whether the son was acquitted of an illegal drug buy or not. In fact, the auction was likely to take place before the son’s case even wrapped up in court.

How is that constitutional?

Ultimately, the elderly couple was granted a reprieve. The officer who showed up to evict them took pity on the man’s health condition and said he’d delay serving the notice to give them time to mount a defense and fight the forfeiture proceedings. But the fact that they had to fight for their own home is egregious. In essence, the couple suddenly found themselves having to thank the government for letting them keep the home that rightfully belonged to them in the first place.

In what alternate universe does the government have the right to boot innocent Americans from their rightfully owned properties? Let’s not forget: Our rights come from God, not government, and so do our properties. And that concept is backed by our legal system.

Private property rights are enshrined in the Constitution in several key amendments – the Fourth speaks to search and seizures; the Fifth speaks to due process; the Fourteenth speaks to the right of life, liberty, and property and denies the state the power to take them without due process. As John Adams made clear: “The moment the idea is admitted into society that property is not as sacred as the laws of God... anarchy and tyranny commence. Property must be secured or liberty cannot exist.”

How right he was. Adams would be shocked to hear some of the private property infringements that go forth at the hands of our government these days.

Traffic officers in one of the busiest drug-smuggling regions in the world, the border area of South Texas, have a history of regularly using moving violations as the jumping point for asset forfeitures. In Kleberg County, Texas, home to about twenty-five thousand residents, the police drive high-performance Dodge Chargers as patrol vehicles and use digital ticket writers that are priced around $40,000 each. The police were able to pay for these high-ticket items because of the $7 million or so they seized in asset forfeitures stemming from various traffic stops conducted over a four-year period. In 2008, one section of Highway 77 roadway proved so lucrative for Kleberg County police that an area sheriff dubbed it a “piggy bank” for the community.26

The big question is, do you feel safer because of asset forfeiture?

Ask Nelly Moreira, an El Salvadorian woman who worked two cleaning jobs at a university in Washington, DC, and at the US Treasury Department. In March 2012, she loaned her car to her son, who was later pulled over by a police officer for a traffic violation. The officer ended up patting him down and found a gun in his clothing. The son was arrested and the officer confiscated Moreira’s car.

A few weeks later, she received a letter in the mail advising that she owed $1,020 in bond money. She thought the money was to get her car back and borrowed the sum from friends. But the bill was actually a “penal sum,” a fee that had to be paid to keep police from sending her car to auction. Worse, paying the fee only secured her the right to contest the seizure of her car. The civil forfeiture appeal process took months – and all along she still had to make payments on her car loan. Meanwhile she took costly public transportation to her jobs.

She finally won back her vehicle, but the public defender who argued her case said another 375 car owners faced the same situation – where their main modes of transportation were seized over minor infractions and stored at locked lots until they paid huge penal sums. The attorney blamed the situation on loose civil asset forfeiture standards that gave the city and police too much power to seize properties.27

Just a couple of months earlier, a man named Victor Ramos Guzman was traveling Interstate 95 by Emporia, Virginia, with his brother-in-law. A police cruiser drove up to them on the highway, peered into their window, and pulled them to the side of the road. The officer said Guzman was driving sixteen miles over the speed limit, but he didn’t issue a ticket. What the officer did do, however, was confiscate $28,500 in cash that was in the car. The officer said the two were acting suspiciously and gave conflicting accounts of why they had the money. But the unclear statements and misunderstandings could just as easily have been due to the men’s inability to speak fluent English. Turns out, Guzman was carrying the cash because the church where he serves as secretary commissioned him to go to Atlanta to conduct a real estate transaction to build a worship center in El Salvador. The church confirmed that to police, but the Virginia State Police called Immigration and Customs Enforcement to check on the men’s legal status – they were lawful US residents – and then confiscated the cash, turning it over to the immigration authorities for safekeeping.28 It took two months, but Guzman and his church finally won back their money. In March 2012, US Customs and Border Patrol cut a check for $28,500 and presented it to Guzman. The law firm that defended Guzman suggested that the police were so willing to break the law to grab the cash because the state’s asset forfeiture law would have allowed Virginia State Police to keep 80 percent of the pot.29

Where’s the due process there?

It seems one easy fix for asset forfeiture abuses would be to reform the system so that properties can be seized only when the owner is convicted of a crime. In truth, that’s not really a reform. That’s simply what the Constitution already says – that property may not be removed or taken without due process of law.

As it stands now, asset forfeitures are cash cows for law enforcement – little more than government-approved theft that adds insult to injury when its proponents audaciously proclaim that such action promotes safer communities.

But these cases of constitutional atrocity often fall under the radar of American consciousness. Why? Most asset forfeitures are reported as one-liners in newspaper crime stories – if at all. The insidious nature of the program often escapes local press scrutiny. Truly, this is an area where the Fourth Estate, the press, could really step up and do some due diligence, uncover and report on how the entire practice is leading our nation further down the road to Big Government and deeper into the pit of a police state.

But with the state of media as it is, don’t hold your breath.