by Dale W. Manor

Introduction

The opening statement of Ruth (1:1) embeds the events of the book in the chaotic era reflected in the book of Judges, when there was no central authority and “everyone did as he saw fit” (Judg. 21:25). Depending on when the Exodus occurred, the span can be either about 1400–1050 B.C. or about 1220–1050 B.C. Not only was Israel embroiled in chaos, most of the ancient world was as well. The Egyptians, Hittites, and Mesopotamians were in general decline; the Greeks were undergoing political upheaval; and the Sea Peoples (which included the Philistines) were wreaking havoc in the Mediterranean basin.

The reasons for these disruptions are difficult to determine, but environmental stresses of some kind, in conjunction with a flurry of earthquakes, may have contributed to the demise.1 This deterioration of the major superpowers allowed a number of smaller peoples and states to germinate in the Levant. Among them are the Moabites, Phoenicians, Syrians, Ammonites, Philistines, and, of course, the Israelites.

A famine in the land (1:1). Famines were not uncommon in the Levant. Sometimes they could be local as prophesied by Amos (Amos 4:7–8), but the phrase normally implies a widespread famine. Several factors could precipitate a famine in addition to lack of rainfall. An adequate amount of rain, but at the wrong time, could destroy the crops.2 Additionally, plant disease (Deut. 28:21; 1 Kings 8:37; Amos 4:9; Hag. 2:17), insect infestation (Joel 1; Amos 4:9–10), and warfare (2 Kings 6:24–25; Isa. 1:7) could effectively serve as famines. The Bible notes a number of famines, some of which precipitated departures from Canaan—Abraham went to Egypt (Gen. 12:10); Isaac sojourned in Gerar (26:1); and Jacob and his family migrated to Egypt (chs. 43–50). Overall, the pattern of famine and plenty in the Levant is unpredictable.

A theological outgrowth of this unpredictability fueled devotion to various fertility deities (i.e., Baal, Asherah, Anat, etc.). The objective was to ensure the rains and productivity of the fields, flocks, and families. Another element likely contributed to their polytheism: Yahweh had promised to provide the full range of their sustenance if they served him faithfully (cf. Deut. 28:1–14). Thus, Israel may have perceived a famine as Yahweh’s failure to provide, especially if they failed to recognize their own apostasy. This attitude seems reflected by Gideon: “If the LORD is with us, why has all this happened to us?” (Judg. 6:13). Similarly, the women informed Jeremiah that when they quit worshiping the Queen of Heaven, famine and disaster had come upon them (Jer. 44:18). From a practical standpoint, the people would attempt to reduce their risk by diversifying their crops and flocks.

Bethlehem (1:1). Bethlehem means “house of bread.” Ironically, the house of plenty has failed Elimelech, forcing his exodus to Moab.

Bethlehem is about five miles south of Jerusalem on the main north-south road that passes along the ridge of the central mountains. The area is generally productive with wheat, barley, almonds, and grapes, which may have factored into the significance of the town’s name.3 This diversification of crops would normally be a valuable survival defense in the otherwise precarious agricultural setting.

Excavations in Bethlehem have been few and no ruins have been found for the period of Ruth, nor has a well been located to which David referred when he yearned for water from the well at the gate of the city (2 Sam. 23:15). Surveys, however, have revealed sherds from the period of the united monarchy.4

Went to live (1:1). The Hebrew word for “live” (gûr) is often rendered “sojourn” and is a technical term applied to a class of people who are neither native nor simply foreigners living in the land. They had no blood ties to the residents and only had legal rights as the dominant peoples permitted,5 which were often whimsically granted and withdrawn. The people of Sodom refer to Lot as an alien (gûr) and use it as a slur (Gen. 19:9).

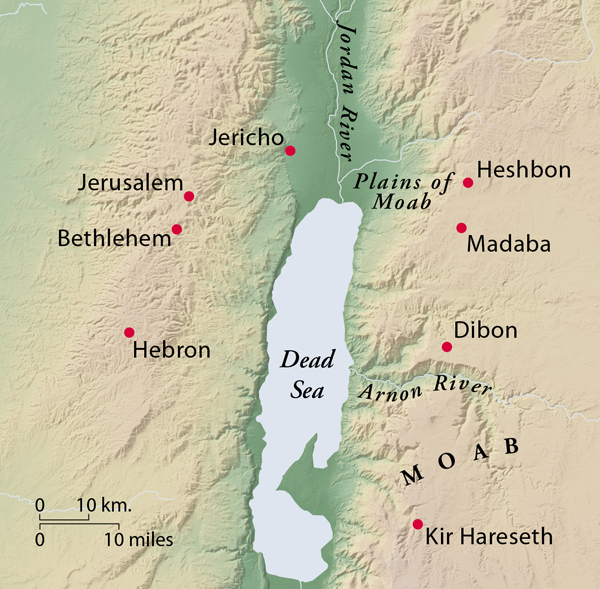

Moab (1:1). Moab, situated east of the Jordan River and Dead Sea, received an annual rainfall of about sixteen inches a year, which provided a number of perennial springs and rivers. The sudden rise of the winds from the depths of the Jordan Valley could wrest more moisture out of the clouds.6 Hence, Moab often sustained or escaped a famine.

Moab, as a geographical or political entity, receives confirmation as early as Rameses II, who refers to Moab on a pylon at Luxor.7 Moab consisted of three main regions. The northernmost section was the plains of Moab to the northeast of the Dead Sea. The middle extended from the plains of Moab southward to the Arnon and was generally a fairly level tableland at 2,000 to 2,400 feet elevation. The third and southernmost section was higher with elevations over 4,000 feet and extending from the Arnon to the Zered at the southern end of the Dead Sea.8

The relationship between Moab and early Israel is difficult to clarify. The Bible notes that Reuben and Gad lived in some of the area later attributed to Moab (Num. 32; Josh. 13:15–28). Mesha, king of Moab (late ninth century), states that the people of Gad had lived in the area “forever.”9 Excavations at Tall al-ʿUmayri in modern Jordan have revealed a town that seems to reflect an early Israelite occupation that was likely Reubenite.10 Since the core of Moab seems to have been to the south, the northern regions may have been much more fluid and multicultural in nature.

The text gives no indication of where Elimelech settled in Moab. To reach the borders, however, would have taken several days since the maximum rate of travel on foot was about twenty miles a day.11 The distance involved in the move made the decision a serious one, inhibiting easy access to the homeland. If he took the family to northern Moab, he would have traveled northward to Jerusalem and descended to Jericho, where he crossed the Jordan into Moab. Alternatively, he may have traveled southward to Hebron, descended eastward to the Dead Sea, crossed the sea to the Lisan (i.e., the peninsula that extends into the Dead Sea) and climbed into the interior of Moab. This would have been the shortest route to Moab.12

The remnants of a wide thoroughfare (ca. 4–5 meters wide) with stone demarcations have been identified in Moab; it appears to date at least to the time of Mesha and almost certainly was built over an earlier road.13 The width of this road is characteristic of the roads throughout the Mediterranean and Mesopotamian regions and is corroborated from the evidence of wagons, chariots, and carts from the ancient world.14

Names (1:2). With the exception of the wordplay that Naomi injects regarding her own name, the names of the major personalities—Elimelech, Naomi, Mahlon, Kilion, Ruth, and Orpah—have neither meanings nor etymologies that play literary roles in the narrative. The equivalents of Elimelech, Naomi, and Kilion are preserved in Ugaritic, Amorite, and/or Akkadian, while Mahlon, Ruth, and Orpah have not been identified elsewhere.15

Ephrathites (1:2). The matriarch Rachel had died on the way to Ephrath (Gen. 35:16–19), which was an earlier name of Bethlehem. The use of Ephrathite may reflect an old aristocratic family of Ephrath/Bethlehem from which Elimelech descended.16

Elimelech . . . died (1:3). After Elimelech died, Naomi was left a widow, and after the deaths of her two sons, we may infer that she is stripped of all male protection except reliance on Yahweh (see sidebar on “The Widow in Ancient Society”). Her plight, then, was similar to that of the orphan and sojourner (e.g., Mal. 3:5) and the poor (e.g., Isa. 10:2). The lapse of ten years (Ruth 1:4) implies that Naomi is past childbearing, or at least near the end of such, and hence her prospect of finding a husband is significantly reduced. Her decision to return to Bethlehem was the most reasonable option, where she might at least find sustenance by gleaning if no extended family members were to care for her.

Sons . . . become your husbands (1:11). The Bible provides specific legislation for family preservation, often called levirate marriage (Deut. 25:5–10): If a man married a woman and he died before there were offspring, his brother would marry the widow and raise up children in the name of the deceased (see sidebar on “Levirate Marriage”). Since Naomi does not mention the prospect of marrying her husband’s brother, technically, her proposed scenario would not be levirate marriage since the husband she might hypothetically secure would not, in a patrilineal society, produce levirate brothers to her deceased sons. However, in Naomi’s distraught state, she is likely unconcerned with the nuances of law; instead, she emphasizes how futile is any prospect of securing any husband for her widowed daughters-in-law.

Her people and her gods (1:15). While “people” and “gods” may refer to Orpah’s personal allegiances, they also may extend to her tribe’s social and religious associations.17 Ancient societies often had a hierarchical slate of deities who resided in their area—sometimes connected with geography or geographic features. This is indicated when the Aramaean king’s servants described Israel’s gods as “gods of the hills” and not of the valleys (cf. 1 Kings 20:23–25). A god’s domain, however, might expand geographically through conquest as indicated in Assur-nasirpal’s bombastic self-description and the sponsorship of a host of Assyrian deities.18 These national gods apparently were often considered beyond the reach of the common person, who alternatively appealed to an array of lesser deities and spirits more easily accessible and task specific19—hence, the proliferation of personal family worship that may have been at odds with the national religious expression.

The national god of Moab was Chemosh. Mesha, a later Moabite king, commented that Chemosh had been angry with the land and permitted Omri to subdue the country.20 Chemosh was an ancient god in the Levant for whom we have evidence as early as the late third millennium B.C. at Ebla. We have no evidence of what he looked like at the period, although he may have been a god of war similar to the Mesopotamian god Nergal.21

But Ruth replied (1:16–17). Ruth’s commitment to leave her family for a land where she apparently has never been, potentially totally isolating herself from her own kin, commands admiration and respect. While she has probably become familiar with some Hebrew customs and beliefs, to saturate herself in the different culture has dimensions that one can only appreciate by experience. Some suggest that her loyalty surpasses that of Abraham, who was called by divine direction (Gen. 12:1–5); Ruth was not.22

To most Westerners, there is usually little emotional trauma in being buried away from the family plot. Such a casual approach to death was unknown to the people of ancient Canaan. Ruth’s declaration is emphatic—“there I will be buried”—that is, with you, Naomi.

The whole town was stirred (1:19). The Hebrew word rendered “stirred” elsewhere denotes considerable excitement and commotion (cf. 1 Sam. 4:5; 1 Kings 1:45). The women’s reaction (which the text indicates) implies that Naomi has made few, if any, visits to her hometown in the intervening ten years. News of Naomi’s arrival probably buzzed through the town. Ancient towns were little more than small villages. Demographic studies indicate that the typical village had a population of only a few hundred.23 Moreover, the population of the town may have diminished because of the famine—either by death or by emigration (as Elimelech and his family had done).

Barley harvest (1:22). Barley and wheat were usually sown at the same time, but barley matured a month before wheat and was harvested in mid-to-late April. Barley was not the preferred grain of consumption—it yielded a course, hearty bread. Since barley matures first, though, it was suitable as the firstfruit offering (Lev. 23:10). The arrival of the barley was a time of rejoicing and heralded the prospect of security as the remaining crops came in.24

Clan of Elimelech (2:1). The “clan” (Heb. mišpāḥâ) was a social grouping in size between that of the tribe (Heb. šēbet or matteh), such as Judah, and the extended family (Heb. bêt ʾāb; lit., “house of the father”). The clan definition was based on descent from a common ancestor, and from within this context the function of the kinsman-redeemer (Heb. gō ʾēl; Lev. 25) in the narrative will unfold. The clan was normally responsible for maintaining the social and economic survival of the relatives and in time of crisis even contributed personnel to the defense of the emerging tribal-based nation.25

A man of standing (2:1). The Hebrew phrase (gibbôr ḥayil) is often rendered “mighty man of valor” (cf. Josh. 6:2; 2 Kings 5:1), but sometimes it simply refers to a person of ability (1 Kings 11:28) or of wealth (2 Kings 15:20).26 The connection with wealth suggests that the “man of valor” was wealthy enough to leave his place of livelihood, having his own weapons of war to serve as necessary when there was not a standing army. Even though there is no evidence of military conflict or turmoil in the book of Ruth, Boaz’s description as a gibbôr ḥayil may be significant since the events are placed within the context of the chaos and anarchy of Judges (Ruth 1:1), when there was occasional need to call people for military duty (cf. Judg. 3:37; 4:10; 7:1, 23).

Pick up the leftover grain (2:2). This is commonly called gleaning. Mosaic law had decreed that landowners were not to harvest the full extent of their fields, but they were to leave produce in the hard-to-reach areas. The remaining harvest was for the poor and foreigners who might be in the land (Lev. 19:9–10; Deut. 24:19–22). Ruth expects to gather the cut remnants that the reapers have accidentally dropped. Obadiah (Obad. 6) and Jeremiah (Jer. 49:9) allude to the expectations of gleaning in their indictments of Edom.

In whose eyes I find favor (2:2). Even though Mosaic law prescribed the landowner to permit gleaning, part of the challenge of the period of the judges was that the people did not generally follow God’s law. Ruth’s statement implies not only an awareness of etiquette to request permission, but also the danger to herself, particularly as a foreigner. Later prophets reveal that the Israelites did not always follow God’s direction relative to the poor and oppressed (cf. Isa. 1:17; Amos 5:10–15; 8:4–6; Mic. 3:1–3), and almost certainly this abuse would often manifest itself in the refusal to allow them to glean.

Corroboration of this is the Egyptian instruction from the Ramesside period: “[Do not] pounce on a widow when you find her in the fields. And then fail to be patient with her reply.”27 It is not clear if this instruction reflects a widespread custom or law in Egypt or if it simply represents Amenemope’s perception of civility and humanitarianism.

Behind the harvesters (2:3). Whether the harvesters were from Boaz’s household cannot be ascertained. The Bible notes that natives and foreigners might hire themselves out for work (Deut. 24:14), either on a daily basis (Lev. 19:13; Deut. 24:15; cf. also Matt. 20:1–16) or annually (Lev. 25:53). The Laws of Eshnunna specified a shekel of silver for a month’s wages, plus a grain provision.28 The Code of Hammurabi decrees a per diem wage29—for the first half of the year, it was to be six barleycorn of silver per day and for the second half, five barleycorn per day.30

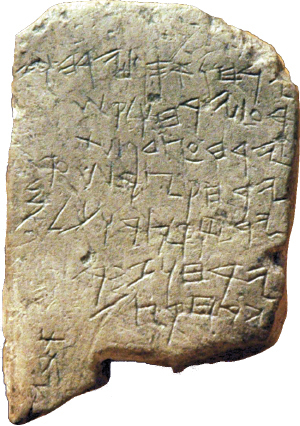

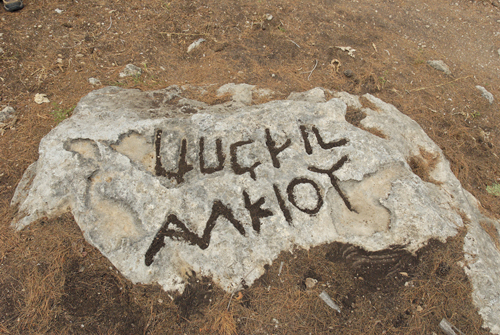

We do not know the pay scale for the time of Ruth in Judah. Harvesting crops apparently was not a favored occupation (cf. Job 7:1–2; 14:6), and the harvester’s welfare would inevitably be at the mercy of the overseer (Jer. 22:13; Mal. 3:5). An inscription from the time of Josiah preserves the petition to the regional magistrate of a reaper whose cloak had been appropriated by the overseer.31

The harvesters probably used flint sickles to cut the grain. Numerous flint sickle blades have been discovered at sites all over Israel from the Iron Age I period (i.e., 1200–1000 B.C.),32 the probable period of the events of Ruth. Even though the period is often referred to as the Iron Age, use of iron was initially rare. Weapons and tools were usually of bronze or, in the case of harvest work, flint. During Saul’s reign, the Philistines dominated iron-working (1 Sam. 13:19). Recent excavations at Tel Beth-Shemesh have uncovered the earliest ironsmith workshop (tenth to ninth century B.C.) found in the Near East.33

A field belonging to Boaz (2:3). People typically lived in a small town or village, which provided safety as well as a sense of community, especially since the people were usually tribally related. The population of the town seldom exceeded a few hundred. The fields were away from the town, and it was necessary for the people to leave the security of town to work in the fields.

The fields were marked off in family plots, often with small piles of stones serving as the boundary markers. It would be somewhat easy for an unscrupulous person to move these stones over a little at a time to increase his land holdings at the expense of a neighbor. Reflecting this reality, the Bible has injunctions against illicitly moving the boundary markers (Deut. 19:14; 27:17; Prov. 22:28; 23:10; cf. Job 24:2; Hos. 5:10). A similar prohibition against land theft with instructions for compensation appears in Hittite laws.34 The small piles of stones and sometimes low walls were convenient means by which to remove the stones from the cultivable fields.

“The LORD be with you!” “The LORD bless you!” (2:4). This exchange of greetings imploring the Lord is not unusual. It may denote an element of devotion, but it may also simply have been a customary greeting; however, the tone of the book implies more than a cultural accommodation. The psalmist in Psalm 129 uses agricultural imagery to describe the interaction with his enemies; the final verse (129:8) implies that a blessing including the divine name was common. One greeting in the Hebrew Bible was simply “shalom” (šālôm), meaning “peace” (cf. Judg. 6:23; 1 Sam. 25:6; 2 Sam. 18:28).35 Some inscriptions have been preserved that implore blessing from both Yahweh of Samaria and his Asherah.36

The foreman (2:5). The Hebrew word na ʿar is sometimes translated “young man,” but the term encompasses much more. Ugaritic and Egyptian sources use a cognate word to refer to people of military rank.37 Similarly, people in the Bible who are so designated are often servants or retainers of some kind (cf. Num. 22:22; Judg. 7:10–11; 19:3; 2 Kings 4:12) or military personnel (Gen. 14:24; 1 Sam. 25:5; 2 Sam. 2:14; 1 Kings 20:14). The term can apply to someone who manages an estate, as was the case with Ziba, who had custody of Saul’s estate (2 Sam. 9:9; 19:17 [19:18]).

As far as age is concerned, the age of demarcation varies depending on the function of the person involved—for military service, it was age twenty (cf. Ex. 30:14; Num. 1:3, 18); for Levitical service outside the Tent of Meeting it was twenty-five (Num. 8:24); and for service in the Tent of Meeting it was thirty (see Num. 4). Several signet impressions with the term na ʿar have been found from the biblical world. Four read “Belonging to Elyaqim steward [na ʿar] of Yokin”—two are from Tell Beit Mirsim, one from Tel Beth-Shemesh, and one from Ramat Rahel.38 The term also appears on an Ammonite seal.39

From morning till now (2:7). The Hebrew text is difficult to decipher. The NIV opts for a rendering that describes the agricultural custom of rising early to work in the fields. Farmers typically rise at or before dawn to take advantage of the cooler morning temperatures. In preindustrial societies and especially in a hot climate like Israel’s, it would be normal to take an afternoon break or siesta during the heat of the day and resume the field work in the later afternoon. This is part of the tradition behind David’s late afternoon walk on his roof after his rest (cf. 2 Sam. 11:2).

Short rest in the shelter (2:7). Again the Hebrew is difficult. The NIV renders this verse to reflect Ruth’s industriousness: She has not stopped working “except for a short rest in the shelter.” Work in the hot sun can quickly drain one’s energy. The shelter was a kind of brush arbor set up as a break shade for the workers. Because of Israel’s low humidity, retreat into the shade yields a dramatic differential in temperature since the dry air rapidly evaporates the perspiration and accentuates the cooling effects.

Follow . . . after the girls (2:9). In the division of labor, the men did the cutting (2:15) and the women (n e ʿārôt, feminine plural form of na ʿar) did the binding (2:8–9), although this separation is not necessarily absolute.40

I have told the men not to touch you (2:9). Ruth’s presence on the scene as a stranger and especially as an alien would naturally draw attention and almost invite abuse by some in society. The word “touch” (nāga ʿ ) carries several nuances, including to strike (Gen. 32:26, 33 [32:25, 32]; Josh. 8:15; Job 1:19), to inflict injury (Gen. 26:11, 29), and to have sexual relations (Gen. 20:6; Prov. 6:29). Unless Boaz suspected his employees to be of the basest sort, it is unlikely that sexual relations (i.e., rape) would be the point of prohibition; more likely it is not to strike or abuse her and may prohibit verbal abuse (cf. comments on 2:2).

Water jars (2:9). Instead of touching her, the young men were to permit her to drink from the jars that the young men had filled. Without a readily available water supply in the field, it was necessary to prepare for the day’s activities. The water source was likely the well at the gate of Bethlehem that David longed for later during his flight from Saul (2 Sam. 23:15–16 = 1 Chron. 11:17–18). The location of the well has not been identified.

While not necessarily exclusively so, drawing water was commonly a woman’s job (Gen. 24:11, 13; 1 Sam. 9:11); note Ugaritic materials here.41 The Israelites sometimes coerced foreigners into the job (Deut. 29:10; Josh. 9:21–27). The jars were likely somewhat porous and allowed the water to seep through the pores. The low humidity accelerated the evaporation from the surface of the jar and cooled the contents of the jar significantly.

Her face to the ground (2:10). While we cannot be sure of the posture involved, the Black Obelisk depicts Jehu of Israel bowing before Shalmaneser III with his face on the ground.42 Yamauchi suggests that the posture is similar to the modern Moslem who places his forehead to the ground in his daily prayers.43

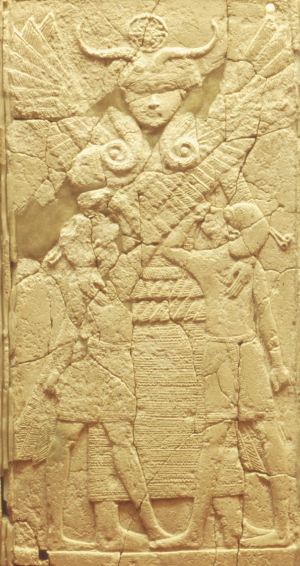

Under whose wings (2:12). The Hebrew word for “wing” is kānāp, which is rendered “corner of your garment” in 3:9, when Ruth broaches the subject of marriage. In the present case, Boaz likely simply alludes to the protective covering of the Lord’s care. The Lord elsewhere is portrayed as providing such protection (see Ps. 36:7; 57:1; 61:4; 91:4). Occasional artistic depictions of deities spreading their wings over their subjects can be seen in a Syrian goddess spreading her wings over two children who nurse at her breasts.44 An Egyptian statue depicts Horus as a falcon hovering behind the king, Khafre,45 and another shows Isis’s wings surrounding Osiris protectively.46 Boaz’s imagery might draw from the wing-protected ark of the covenant with its cherubim (Ex. 25:17–22).47

At mealtime (2:14). The day’s meals normally began with a light breakfast and a light noon meal, such as reflected in this narrative. The evening meal was the main meal of the day and usually consisted of basically a one-pot stew of mainly vegetables; the stew was sopped with bread.48 The wine vinegar (ḥōmeṣ) was a soured wine that was among the prohibitions for Nazirites (Num. 6:3). In this passage it may have been a vinegar-based sauce.49

An inscription preserved from Arad lists ḥōmeṣ as a requisitioned commodity along with wine;50 however, earlier Ugaritic materials seem to list it as a synonym of wine.51 Linguistically, the item could render a commonly used chick pea sauce (hummous), prevalent throughout the Mediterranean world, into which bread is dipped.52 The roasted grain was a common addition to the meal (1 Sam. 17:17; 25:18; 2 Sam. 17:28). Robinson had noted in his travels in 1838 that “the grains of wheat not yet fully dry and hard are roasted in a pan or on an iron plate,”53 although Borowski suggests that the parching was done because the grain was too hard to be eaten raw without breaking the kernel.54

Threshed the barley (2:17). To thresh this personal harvest for her and Naomi, Ruth beat the grain with a stick to separate the grains from the chaff (cf. Gideon in Judg. 6:11). It would be necessary then to winnow it as well. Her take for the day was impressive—an ephah (ca. twenty-two liters = two-thirds of a bushel) is an exceptional quantity and implies that the workers complied with Boaz’s request. This was the same amount that Jesse instructed David to deliver to his three brothers serving in Saul’s army (cf. 1 Sam. 17:13–17).

|

Xēstes

|

Greco-Roman

|

1/2 cab

|

1 1/6 pints

|

|

Cab

|

Hebrew

|

1/18 ephah

|

1 quart

|

|

Choinix

|

Greco-Roman

|

1/18 ephah

|

1 quart

|

|

Omer

|

Hebrew

|

1/10 ephah

|

2 quarts

|

|

Seah/Saton

|

Hebrew/Greek

|

1/3 ephah

|

7 quarts

|

|

Modios

|

Greco-Roman

|

4 omers

|

1 peck or 1/4 bushel

|

|

Ephah [Bath]

|

Hebrew

|

10 omers

|

3/5 bushel

|

|

Lethek

|

Hebrew

|

5 ephahs

|

3 bushels

|

|

Cor [Homer]/Koros

|

Hebrew/Greek

|

10 ephahs

|

6 bushels or 200 quarts/14.9 bushels or 500 quarts

|

The living and the dead (2:20). Some cultures worked to maintain the dead by giving food offerings and sacrifices on their behalf.55 There is no indication that Naomi has this in mind; she more likely alludes to God’s preservation of the memory of the dead (i.e., Elimelech, Mahlon, and Kilion) by taking care of their widows (i.e., Naomi and Ruth). She recognizes that Boaz is a potential source of hope as their kinsman-redeemer (gō ʾēl). The role of the kinsman-redeemer was multifaceted and served to stabilize a disrupted family circumstance.

Barley and wheat harvests (2:23). The time involved would normally be two to two and a half months, taking the wheat harvest into June. If the narrative is chronological, the barley winnowing (see ch. 3) was apparently put on hold until the wheat harvest had come in. If this is the case, it implies a significant harvest in view of the recently terminated famine.

Winnowing barley (3:2). Winnowing was often done as a community activity. Winnowing takes place after the threshing (see below), and it is a labor-intensive process to separate the grains from the plant stalks. The process was conducted typically outside of the town where the person, using a pitchfork, threw the mixture into the air. The breezes blew away the unwanted, lighter components (cf. Hos. 13:3), allowing the heavier grains to fall to the ground. The process would be repeated until the grains were relatively free from the plant stalks.56 The breezes usually came up in the mid-afternoon and died out about sunset; it is possible that Naomi’s reference to Boaz winnowing at night (3:2) accommodates the festivities that normally followed a successful harvest and winnowing.

Transport of the grain to the threshing and winnowing floor was either on animal-drawn carts (cf. Amos 2:13) or in baskets.57 The threshing floor was a large flat area, usually bared bedrock and slick from the polishing effect of the intensive activity with the straw acting as a polishing agent.58 They were situated to take advantage of the prevailing winds, which were critical. Sometimes these were near the city gates (cf. 1 Kings 22:10; Jer. 15:7).59

Threshing could be done several ways. Ruth had beaten out her fairly small volume with a stick (2:17). A larger volume, however, required more intensive and efficient threshing. Sometimes animals would walk over the grain and their hooves beat the grain to separate the grain from the stalk (cf. a metaphorical allusion in Mic. 4:13). Mosaic legislation demanded that the animals be allowed to eat of the harvest (Deut. 25:4). A more efficient tool was a threshing sledge, which was pulled by an animal or two (cf. metaphor in Isa. 41:15). This consisted of two to three wide boards with upturned ends to slide easily over the grain; the underside of the boards would have holes drilled or slots cut into them into which teeth of flint or iron were driven. The teeth separated the components of the grain. Isaiah also alludes to the wheels of carts along with the animals’ hooves being used to thresh (Isa. 28:28).

Uncover his feet (3:4). The instruction can be seen as a double entendre. Sometimes “feet” (r egālîm) is a euphemism for the genital region (cf. Isa. 7:20; Ezek. 16:25;60 some extend it to Ex. 4:25; Judg. 3:24; 1 Sam. 24:3), but most of the time r egālîm means feet. Complicating the interpretation, however, is the use of “uncover” (gālâ), which sometimes referred to sexual relations (Lev. 18 and 20 numerous times; Deut. 23:1 [22:30]; 27:20; Ezek. 16:35–39). More specifically, though, Naomi instructs Ruth to uncover “the place of his feet” (marg elôt),61 and given the character reflected of both Boaz and Ruth, there is no reason to infer that anything more than uncovering the feet occurs.62

Far end of the grain pile (3:7). Probably Boaz remained at the threshing floor to protect against thieves.

Spread the corner of your garment . . . kinsman-redeemer (3:9). As to what startled Boaz awake is not revealed, but it likely was the subconscious realization that someone was nearby. Ruth’s request is an idiom for marriage. The phrase “corner of your garment” is (kānāp), which applies to either a wing or the edge of a garment. The phrase is the same as applies to marriage when God later described his marriage to Israel (Ezek. 16:8).63 The imagery brings to mind Boaz’s own blessing of coming under the Lord’s wing for protection (2:12). Ruth explains that the invitation is important because he is her kinsman-redeemer. Boaz appears to understand the request as no more than a marriage proposal.

All my fellow townsmen (3:11). The Hebrew phrase literally translates “all the gate of my people.” It is a metonymy to the organization of ancient towns—all the people passed through the gate to work out in the fields, and at least in the case of Bethlehem, the well was near the gate (2 Sam. 23:15–16); hence, the phrase alludes to all the people. See sidebar on “Ancient City Gates” at 4:1–2.

Six measures (3:17). The measure is not identified, but it would not have been six ephahs, which would equal approximately two hundred pounds. The seah is more likely, six of which would equal sixty to ninety pounds. An alternative would be an omer, which was approximately one-tenth of an ephah, in which case the amount would be a little over half the quantity she had gleaned in her first outing (cf. 2:17).

The town gate (4:1). Most Canaanite and Israelite towns were on hills and were walled in some way; hence, they required a gate for access and egress. Since the fields and usually the water supply were outside the town (the water supply was usually outside the city near the foot of the hill; cf. 1 Sam. 9:11), most people passed through the gate sometime during the day. The gate of the town, therefore, became a scene of social significance.

Kinsman-redeemer (4:1). See sidebar on “The Role of the Kinsman-Redeemer” at 2:20.

Ten of the elders (4:2). References to elders who oversee the people of antiquity appear in the Epic of Gilgamesh64 and in Hittite law.65 The Bible indicates that Moab and Midian had elders (Num. 22:4, 7), as did the Gibeonites (Josh. 9:11). The term “elder” (zāqēn) derives from a word meaning “beard” and alludes to one who is of advanced age.66 Over time, however, the term came to apply as well to administrators of the affairs of the community. They are assumed to be people who have experienced sufficient vicissitudes of life to be able to tap into those experiences to guide the community (cf. 1 Kings 12:6–11; Job 12:20; Jer. 26:17–19). Elders also sometimes represented the people before God (Lev. 4:13–15) and oversaw murder trials and questions of asylum (Deut. 19:11–12; 21:1–9; Josh. 20:1–6) and disputes regarding virginity (Deut. 22:15–19). They also served as social witnesses to issues of the kinsman-redeemer and levirate marriages (Deut. 25:5–10; Ruth 4:9–11).

The Bible notes that there were elders over tribal and clan affairs (e.g., Judg. 11:5) as well as nationally (cf. Deut. 31:28). In addition, cities had their own appointments (cf. Deut. 19:11–12). How many elders a town should have is not indicated in the Bible. Gideon was informed that Succoth had seventy-seven elders and officials (Judg. 8:14). Ruth 4:2 indicates that there were more than ten for Bethlehem (i.e., “ten of the elders”).

The dead man’s widow (4:5). See sidebar on “Levirate Marriage” at 1:11.

Name of the dead (4:10). A similar explanation appears in the levirate marriage legislation (Deut. 25:6). “Name” (šēm), however, does not serve just as nomenclature; it also refers to being remembered and honored, a kind of eternal life in having offspring to connect with the deceased.67 Its broader use has to do with inheritance and “the reality and significance of a man’s deeds and life.”68 If a man had no sons, the name might be preserved through daughters, as implied in the request of Zelophehad’s daughters and their petition to Moses (Num. 27:1–11); however, they were required to marry only within their own tribe (Num. 36).

Might endanger my own estate (4:6). This closer relative fails to elaborate how serving as the gō ʾēl with Ruth as part of the deal would endanger his estate. Since the purpose of the levirate marriage concern was to perpetuate the name of the deceased, the inheritance would be through another’s line rather than the redeemer himself. An investment to redeem the land for Naomi, who was apparently past child-bearing (cf. 1:11–13), would likely keep the property in his own line, but the prospect of marrying Ruth, who came with the property and the implied responsibilities, would indicate that not only would the investment to redeem the property be forfeited to any offspring that might be born, but there would be the added burden of supporting Ruth and Naomi, as well as any additional offspring that might come from the union.

Removed his sandal (4:7–8). The introductory phrase of verse 7 indicates that some time has passed from the events of the narrative and its retelling, although the term “earlier times” (l epānîm) can refer to a single generation’s separation (cf. Job 42:11). The text implies that the kinsman-redeemer relinquished his sandal to Boaz. The image derives from property rights and the right of the person who owns a piece of land to be the one who walks on it. God had revealed to Abraham that wherever he might walk in Canaan, the land would belong to him (Gen. 13:17). This foot placement motif is reflected in the Nuzi materials in which “to make a transfer of real estate more valid, a man would ‘lift up his foot from his property,’ and ‘placed the foot of the other man on it.’ ”69

With similar imagery, God declares possession of Edom with the metaphor of casting his sandal over the land (Ps. 60:8; 108:9).70 The difference between the widow’s snatching the sandal off the foot of the reluctant brother-in-law (Deut. 25:9) and the demeanor exhibited in Ruth is likely that the legal focus of the transaction is property redemption and not levirate marriage. Furthermore, Ruth has someone who has agreed to be the redeemer; therefore there is no need to humiliate the next of kin.

May the LORD make . . . like that of Perez (4:11–12). Boaz’s declaration elicits recognition from the witnesses (i.e., the elders), who pronounce a tripartite blessing on the pair. The first blessing seeks fruitfulness: May the Lord make the bride fruitful, as Rachel and Leah were, from whom the tribes of Israel came. The second blessing seeks recognition and respect in their community, Bethlehem (Ephrathah parallels Bethlehem; cf. Gen. 35:16; see comment on Ruth 1:2). The third blessing repeats the second seeking recognition and respect—it appeals to Perez, who was the Judahite son through whom the Bethlehemites had come and through whom they perceived their own greatness (and through whose line King David would come; cf. Ruth 4:18–22).

This tripartite type of blessing mirrors a similarly structured blessing in Ugaritic literature, when Kirta marries Hurraya and El pronounces a blessing first of fertility on Hurraya and then twice for greatness for Kirta.71

Your home like Rachel and Leah . . . have standing in Ephrathah (4:11). The appeal is to Rachel and Leah, who were the wives of Jacob/Israel, their progenitor (Gen. 29–30). Four of the tribes claimed their heritage specifically through the handmaids, Zilpah and Bilhah (Gen. 30:1–13), but these women would not be mentioned since the children born to them were considered the offspring of the respective wives, similar to Hagar’s relationship to Sarah (Gen. 16). Some ancient cultures (e.g., Alalakh and Nuzi) permitted the arrangement of a surrogate mother through whom an heir could be produced.72

The desire for a large family was not simply the prestige implied in the numbers, but the practical element of survival. The available archaeological evidence reflects an approximately 35 percent mortality rate by age five; thus, the production of numerous children tended somewhat to compensate for the deaths. Added wealth could be realized by the fact that from an early age, almost all people had roles in the family economy.73 The blessing also imports Perez, the son of Judah and Tamar, from whom the tribe of Judah was descended (Gen. 38). Perez had been born out of trying circumstances demanding the less-than-ideal levirate relationship; hence the people seem to perceive a similarity between Boaz and Ruth with Judah and Tamar.

Better to you than seven sons (4:15). The imagery of seven emphasizes the greatness of Ruth’s contribution to Naomi’s survival and especially as compared to sons. Patrilineal and patrilocal societies place more emphasis on having sons because the women are married off into other families, removing their economic contribution from the father’s family. With patrilineal descent, property tends generally to remain in the male line.74 The compliment of Ruth is therefore especially significant. She has brought Naomi’s life to completion in providing the male heir who would keep the property in the family; they also recognize her underlying devotion to Naomi, which was demonstrated in forsaking her homeland to come to the foreign land of Judah to adopt a new family and a new God.

Bibliography

Block, Daniel I. Judges, Ruth. NAC. Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 1999. A thorough discussion from an evangelical perspective, responding responsibly to a wide range of alternative interpretations.

Bush, Frederic. Ruth/Esther. WBC. Dallas: Word, 1996. Excellent commentary from an evangelical perspective, providing background, textual, and grammatical analysis along with some explanation of structure. Its discussion lends itself well to exegetical application.

Campbell, Edward F., Jr. Ruth. AB. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1975. From a typically liberal perspective, but very good commentary dealing heavily with the grammatical and background discussion.

Cundall, Arthur E., and Leon Morris. Judges & Ruth. TOTC. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 1968. Ruth is written by Morris, who does an outstanding job compressing a wealth of information in a small and inexpensive volume.

Hubbard, Robert L., Jr. The Book of Ruth. NICOT. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1988. A responsibly done commentary with good historical, literary, and linguistic discussion, with more theological discussion and application than most.

Sasson, Jack M. Ruth: A New Translation with a Philological Commentary and a Formalist-Folklorist Interpretation. 2nd ed. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1995. Sasson brings a broad literary and cultural background to his remarks, dealing with the text more from literary perspectives than theological ones. It is probably somewhat difficult for the non-Hebrew reader since much of it is based directly on the Hebrew text.

Younger, K. Lawson, Jr. Judges and Ruth. NIVAC. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2002. An excellent commentary explaining the structure and background of Ruth. It is particularly helpful in bridging the transition from its original setting to modern application.

Chapter Notes

Main Text Notes

Sidebar and Chart Notes

A-2. Karel van der Toorn, “Female Prostitution in Payment of Vows in Ancient Israel,” JBL 108 (1989): 193–205.

A-3. The authenticity of the ostracon is debated; for discussion and translation, see COS, 3:44.

A-4. COS, 2:131 (§§117–18, 171–74).

A-5. COS, 1:35 (spec. 62); COS, 1:36.

A-6. COS, 1:103 (CTA, 17, v 3–33). See also further discussion in F. C. Fensham, “Widow, Orphan, and the Poor in Ancient Near Eastern Legal and Wisdom Literature,” JNES 21 (1962): 129–39.

A-7. For a discussion of the ages of marriage in various ancient cultures see V. Hamilton, “Marriage (OT and ANE),” ABD, 4:559–69.

A-8. COS, 2:132 (§§30, 33, 43).

A-10. M. Burrows, “The Ancient Oriental Background of Hebrew Levirate Marriage,” BASOR 77 (1940): 2–15.

A-11. For a survey of the law and its application, see D. W. Manor, “A Brief History of Levirate Marriage as It Relates to the Bible,” RQ 27 (1984): 129–42.

A-12. R. Westbrook, Property and the Family in Biblical Law (JSOTSup 113; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1991), 69–89.

A-13. H. J. Marsman, Women in Ugarit and Israel: Their Social and Religious Position in the Context of the Ancient Near East (Leiden: Brill, 2003), 299–317.

A-14. For further discussion, see E. M. Meyers, “Secondary Burials in Palestine,” BA 33/1 (1970): 2–29.

A-15. For a catalogue of graves and grave goods from the Iron Age in Judah, see conveniently E. Bloch-Smith, Judahite Burial Practices and Beliefs about the Dead (JSOTSup 123; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1992), 152–245.

A-16. For a background discussion of these beliefs, see T. Abusch, “Ghost and God: Some Observations on a Babylonian Understanding of Human Nature,” in Self, Soul and Body in Religious Experience, ed. A. I. Baumgarten, J. Assmann, and G. G. Stroumsa (Leiden: Brill, 1998), 363–83. Their application in the Old Testament world is discussed in T. J. Lewis, “Dead,” in Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, ed. K. van der Toorn, B. Becking, and P. W. van der Horst (Leiden: Brill, 1995), 421–38.

A-17. ANET, 320. Additionally, see Borowski, Agriculture, 31–44.

A-18. H. Ringgren, “ gū ʾal,” TDOT, 2:350–55. For further discussion, see M. S. Moore, “Haggo ʾel: The Cultural Gyroscope of Ancient Hebrew Society,” RQ 23/1 (1980): 27–35, and R. L. Hubbard, “The gō ʾēl in Ancient Israel: The Theology of an Israelite Institution,” BBR 1 (1991): 3–19.

gū ʾal,” TDOT, 2:350–55. For further discussion, see M. S. Moore, “Haggo ʾel: The Cultural Gyroscope of Ancient Hebrew Society,” RQ 23/1 (1980): 27–35, and R. L. Hubbard, “The gō ʾēl in Ancient Israel: The Theology of an Israelite Institution,” BBR 1 (1991): 3–19.

A-21. See A. Biran, Biblical Dan (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1994), 235–54.

A-22. Danʾel judges the case of a widow in the gate with the elders of his town; COS, 1:103 (CTA, 17, v 3–33).

A-24. Z. Herzog, “Fortifications (Levant),” ABD, 2:844–52.

A-25. A brief discussion of the settlement explosion for the period can be found in W. G. Dever, Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From? (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003), 96–100.

A-26. See conveniently discussion and drawings of plans in ibid., 75–88.