• The UN fails to keep the record

• A bleak 25-year peacebuilding record

• What do global indices show?

One would have thought that the UN itself – or still better, some independent evaluation office within the organization – would be best suited to assess the record of its multidisciplinary operations in making peace sustainable. However, the UN has not even attempted to establish such a record.

This chapter will present evidence to show that the record of UN multidisciplinary operations, in the aftermath of the Cold War, in assisting countries at low level of development to move from civil war or other interstate conflict into a path of peace, stability, and prosperity, is indeed bleak. As part of the analysis, the chapter presents aid data to indicate the degree of aid dependency of many of these countries and presents the rankings of countries in a series of global indices to show the poor state of affairs.

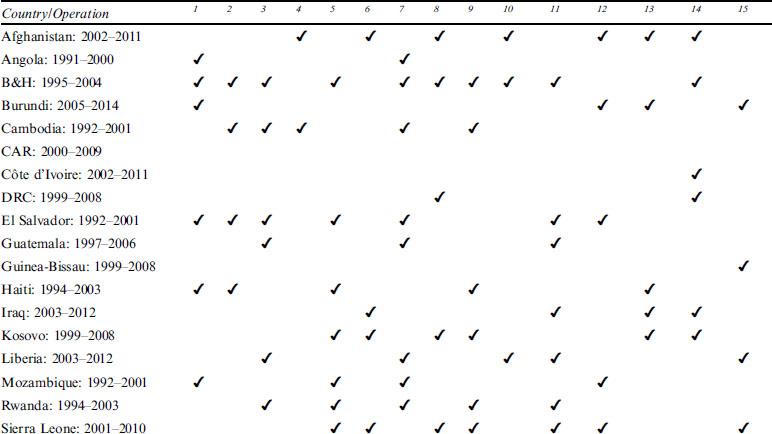

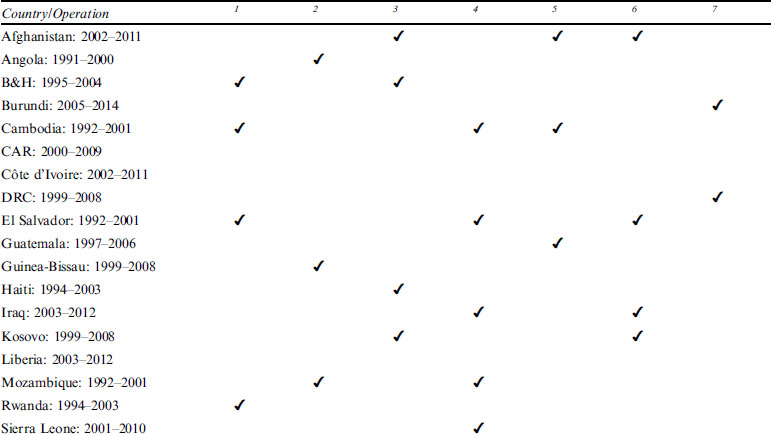

The chapter also presents two tables, each identifying books that include case studies on the 21 UN operations in our sample and listing such case studies by country. While case studies included in Table 6.3 focus mostly on the political, security, and/or social aspects of the transition, those included in Table 6.4 also address the economic aspects that have affected peacebuilding efforts in those countries.

The UN fails to keep the record

In Larger Freedom (2005), Kofi Annan states,

Our record of success in mediating and implementing peace agreements is sadly blemished by some devastating failures. Indeed, several of the most violent and tragic episodes of the 1990s occurred after the negotiations of peace agreements – for instance in Angola in 1993 and Rwanda in 1994. Roughly half of all countries that emerge from war lapse back into violence within five years [emphasis added].1

Because the source is not footnoted, most readers would trust that the percentage came from the UN itself. In fact, most people would think that it is the type of data that the UN should collect. However, in my many interviews with officials over the years, I have found that the UN does not perform this task despite the fact that such data are basic for any analysis of this important matter. Moreover, there seems to be no agreement among high UN officials from where the information that “roughly half … lapse back into violence within five years” was taken (plagiarized perhaps?). Despite it, this statistic has been quoted by many analysts over the years.

Some observers believe that the information came from A More Secure World, the 2004 report of the high-level panel that Annan appointed to make recommendations on improving peacebuilding. It would then be less of a sin to forget referencing it. This report, however, notes only that “[s]tates that have experienced civil war face a high risk of recurrence”2 without specifying any percentage and attributing the findings to the World Bank’s report prepared by Paul Collier and colleagues (Chapter 4). But the World Bank’s report says that, in the first decade of postconflict peace, “the risks of further conflict are exceptionally high: approximately half will fall back into conflict within the decade [emphasis added].”3 The risk of falling into conflict within five or within ten years is quite different.

This raises a number of troubling issues. First and foremost, how is it possible that the UN, as the global organization responsible for the maintenance of peace and security, uses conflict data from a development organization such as the World Bank? Moreover, in their report, The Challenge of Sustaining Peace, the group of experts appointed by Secretary-General Ban to advise for the review of the peacebuilding architecture (Chapter 5), used data from the World Bank 2011 World Development Report (criticized in Chapter 4).4

Second, and just as important, the data is presented without any information about the sample, which tends to vary greatly among different studies. We discussed earlier with regard to the 2011 World Bank report the problems of mixing different types of conflict for analytical and policymaking purposes. Is Annan’s percentage referring to UN operations or to any conflict? In the aftermath of the Cold War or since the end of the Second World War? It is anybody’s guess. Not surprising, there is such a confusion even among serious researchers.

For purposes of establishing the UN record, our sample is restricted to countries at low levels of development coming out of civil war or other intrastate conflict since the end of the Cold War and embarking in a political, security, and socioeconomic transition to peace with the support of UN multidisciplinary operations,5 often in collaboration with the United States, Australia, the United Kingdom, France, or other donors that have a specific interest in the country. That we analyze what happened in these countries during the first decade in transition does not necessarily mean that a UN operation was in place throughout the decade. In fact, many were quite short lived, which was often the problem. But long-term operations also presented their own problems, particularly in terms of distortions created by their presence.

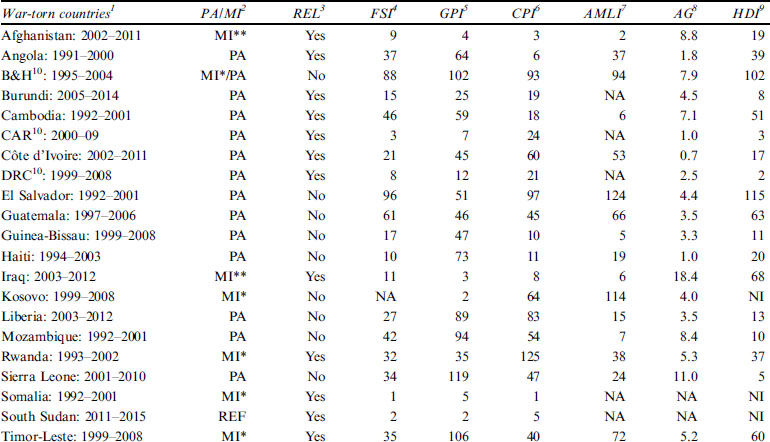

Table 6.1 lists the 21 countries in our sample. To establish relapse, we used the UCDP-PRIO data on conflict, supplemented by information on the UN operation itself. Given the parameters established for the sample, Namibia, for example, is not included since it was not coming out of civil war and the UN peacebuilding support was restricted to organizing elections. By restricting the sample to multidisciplinary operations, where the UN may get involved in supporting productive reintegration of former combatants and other conflict-affected groups, we can expect a higher risk of failure. As argued in this book, the UN is least prepared to deal with the socioeconomic aspects of peacebuilding. The UN has indeed found it easier to support elections than to implement the complex, expensive, and long-term aspect of productive reintegration, which requires the reactivation of the domestic economy without which sustainable employment will not be possible. Table 6.2 shows the disappointing record, despite the large amount of aid that many of these countries received in the transition to peace.

Table 6.1 Performance of war-torn countries with foreign interventions

.jpg)

Sources: Calculated by author using IMF World Economic Outlook Database (April 2016); and latest indices (2015–16).

Notes:

1. Countries with UN operations following peace agreements or military intervention coming out of civil war or other internal conflict (often with regional implications) that embarked in the transition to peace with UN support up to 201. Dates in brackets indicate first decade of the transition. All indices have been updated to end of August 2016.

2. Peace agreement (PA) or military intervention (MI). MI* indicates MI for humanitarian purposes and MI** for regime change.

3. Yes indicates that the country relapsed into some kind of generalized conflict that required intervention, led to large number of refugees, or collapsed the economy. The country may have had some localized conflict from the beginning of the operation. Information on the particular UN operation was used to determine relapse and was checked against UCDP-PRIO data on conflict.

4. FSI is the Failed States Index compiled by the Fund for Peace.

5. GPI is the Global Peace Index compiled by the Institute of Economics & Peace.

6. CPI is the Corruption Perception Index compiled by Transparency International.

7. AMLI is the Anti-Money Laundering Index, a measure of money laundering and terrorist financing, compiled by the Basel Institute of Governance.

8. AG is the average growth rate of the country during the first decade of the transition to peace calculated by the author using GDP growth from the IMF WEO April 2016 databank.

9. HDI is the Human Development Index compiled by the UNDP.

10. B&H stand for Bosnia & Herzegovina; CAR for Central African Republic; and DRC for Democratic Republic of Congo.

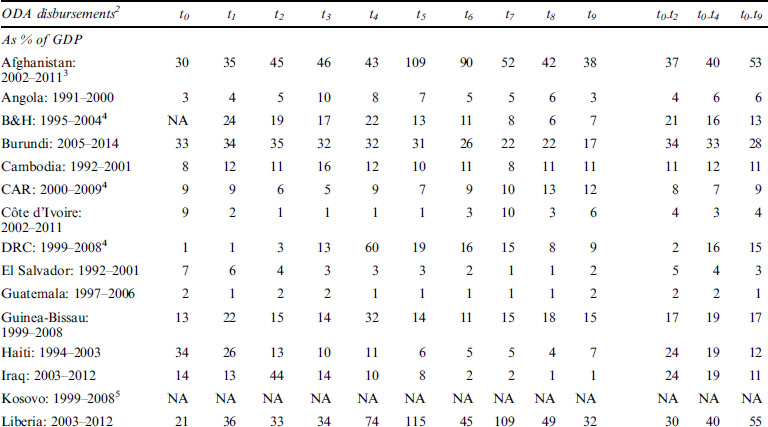

Table 6.2 Aid comparison across war-torn countries

.jpg)

Source: Calculated by author using data from World Economic Outlook Database (April 2016); OECD total aid based on official development assistance (ODA) (August 2016)

Notes:

1. ODA (Official Development Assistance) disbursements during the first decade of the transition to peace; it also reports the average aid flows during the first 3 years (t0-t2), 5 years (t0-t4), and 10 years (t0-t9).

2. ODA includes grants, loans and debt relief from all donors to developing countries and territories and to multilateral agencies which are: (a) undertaken by the official sector; (b) with promotion of economic development and welfare as the main objective; (c) at concessional financial terms (if a loan, having a grant element of at least 25 per cent). In addition to financial flows, technical co-operation is included in aid. Grants, loans and credits for military purposes are excluded. Transfer payments to private individuals (e.g. pensions, reparations or insurance payouts) are in general not counted.

3. Data for Afghanistan was adjusted in 2008-09 to account for $8.8 billion debt relief from Russia which does not report data to the OECD.

4. B&H stand for Bosnia & Herzegovina; CAR for Central African Republic; and DRC for Democratic Republic of Congo.

5. OECD only reports ODA data on Kosovo since 2009; IMF WEO does not report data on Somalia.

Because in some of these countries some donors have played a critical role and have affected the transition both positively and negatively, and the same is true of the Bretton Woods institutions and other foreign interveners, it would be unfair to blame only the UN if these countries revert to war.

In addition to the involvement of many foreign interveners in the country itself, another aspect that needs to be taken into consideration when analyzing the UN record in these countries is that, while they have experienced intrastate conflict of some sort, many of them have been affected by neighbouring countries in positive and negative ways, both during and after the conflicts, and in turn have had contagion effects of various kinds on them.

So, as with any other evaluation or statistical analysis, many factors affecting the different countries in the transition to peace, stability, and prosperity need to be considered carefully and rigorously before any conclusions can be drawn.

A bleak 25-year peacebuilding record6

In an effort to build societies in the image of those of advanced countries, foreign interveners have tried to convert – practically overnight – insecure and destitute societies into liberal democracies with free-market economies, predominant private sectors, and independent central banks. Imposing such an unrealistic agenda on poor, polarized, mismanaged, and war-ravaged countries could reflect the ideological belief that only societies based on principles of democracy and free markets are capable of achieving and preserving peace and stability and of generating increased prosperity. It most probably represents efforts – particularly in countries rich in natural resources – to create adequate conditions where companies, contractors, and experts from donor countries can flourish.

The recipe has invariably been a combination of centralized government with early and relatively free national elections together with peacekeeping or counter-insurgency operations to keep the peace, humanitarian assistance to save lives and provide minimum levels of consumption, and a few large and relatively productive investment projects requiring new and expensive infrastructure that takes time to build. This recipe has benefitted mostly foreign investors and a few domestic elites, leading to increasing income inequality and little gains in poverty alleviation. Generally lacking a peace dividend for the large majority of the population – that is, a significant improvement in their lives and livelihoods – the recipe has simply not worked and continues to haunt peacebuilding efforts.

As they say, the proof of the pudding is in the eating, and the UN peacebuilding record of the last quarter of a century speaks for itself. Of the 21 countries in Table 6.1 in which the UN set up the type of operations described earlier, 12 have clearly relapsed into conflict (57 per cent) during the first decade of the transition.7 Some of the countries that did not relapse during the first decade, such as Guinea-Bissau, went through more than a decade of recurrent episodes of political instability, including coups d’états and increased drug trafficking.

Some of these countries would have probably relapsed had it not been for costly and long-lasting peacekeeping operations or foreign troops in place to keep the peace. The record would be even worse if we had followed Doyle and Sambanis, who rightly code operations as “peacebuilding success” only if peacekeepers and military forces (which were keeping the peace) have left for at least two years.8 Thus, Liberia would not be a success in keeping the peace since peacekeepers still linger in the country after more than a dozen years. It is yet to be seen what will happen when peacekeepers finally exit (Chapter 5).

Both Cambodia and Timor-Leste relapsed after the UN had filed them away as peacebuilding successes. In the case of Cambodia, the 1997 coup “raised questions about the merits of a nearly two billion dollar peace implementation operation that, just four years earlier, had congratulated itself for helping to resolve the country’s internal divisions democratically.”9 Despite being included among those that did not relapse into conflict during the first decade, Haiti relapsed in the eleventh year.

Of those that managed to keep an unsettled peace, the large majority have ended up unable to stand on their own feet and have fallen into an aid trap. As an illustration, after more than two decades of peace and large volumes of aid, Mozambique is ranked among the lowest five percent of all countries included in the 2015 Human Development Index (HDI). This is particularly appalling since it was better ranked – among the bottom 10 percent – in 1992, the year in which the peace agreement was signed.

Afghanistan has the ominous record of having both returned to conflict and fallen into an aid dependency from which it will take decades to detox. The latter is also true of Liberia, where the UN has kept the peace. In these two most aid-dependent countries, aid flows increased over the decade rather than decreasing, as it should have.

As Table 6.2 indicates, the level of aid that these countries received over the first decade in the transition varied greatly depending on the geopolitical interest of donors (Afghanistan, Iraq, Haiti), on historical ties (Liberia), on whether they had access to concessional financing from the international financial institutions or not (as El Salvador or Guatemala), on their own resources (Angola), or whether they were outside the radar of donors (the so-called aid orphans). Even those such as El Salvador that managed to avoid relapsing into war and becoming aid dependent have not made any socioeconomic improvement, with the country still ranked at the bottom 40 percent in the HDI, as it was in 1992.

Table 6.1 shows that many of the countries in the sample grew fast during the first decade in transition, although from low levels. In fact, five of them grew at average rates of 7 to 18 percent throughout the decade. The problem is that growth in most countries was neither inclusive nor sustainable and created all kinds of distortions to relative prices and resources in general that would continue to affect the countries’ growth and development for years to come. Chapter 7 will provide country evidence.

What do global indices show?

If we look at how the countries in our sample perform over time in the different global indices, it is not a pretty picture (Table 6.1). Different global indices illustrate the seriousness with which corruption, illicit activities, conflict, lack of governance, and lack of inclusive socioeconomic opportunities have affected current conditions in many of these countries in interrelated and convoluted ways. These factors also affect a country’s chances of ever becoming stable, peaceful, and prosperous.10

The three most aid-dependent countries – Afghanistan, Liberia, and Mozambique – together with seven more in which the UN has provided long and expensive support over long periods of time are among the 25 worst performers in the HDI. As we mentioned above, the HDI shows that some are relatively worse off that they were at the time they started the transition.

As Transparency International notes, five of the 10 most corrupt countries in the world also rank among the 10 least peaceful places. Lack of peace in turn affects prosperity and development. Although on their own the different indices may be difficult to interpret, taken together they tend to give a rather realistic picture of what is going on in these countries.

Indeed, the most recent indices available in July 2016 are revealing.11 The Peace Index includes five countries in our sample among its seven worst.12 The Failed States Index includes 11 of these countries among its 25 worst performers, many of which are still at war; the Terrorism Index includes six of them among the 20 worst. Not surprisingly, many of these countries are or have been at the top of the foreign policy agenda of the United States and other major countries. The Corruption Perception Index includes nine of these countries, and the Basel AML Index13 includes seven of them among the 25 worst ranked.

The ineffective way in which peacebuilding is addressed both by the UN and the United States is perhaps best illustrated in the case of Afghanistan, where both have been critically involved.14 In the last two indices just mentioned on corruption and money laundering, Afghanistan is ranked second worst in corruption, surpassed only by North Korea and Somalia (which share the worst place), and only by Iran for money laundering.

The Failed States Index ranked Afghanistan in the eighth worst place, only slightly better than Syria and Yemen, both at war. The Peace Index ranked Afghanistan in the fourth worst place, after South Sudan, Syria and Iraq, also at war.

In the Terrorism Index, Afghanistan came second worst, after Iraq. These two countries, together with Nigeria, Pakistan and Syria, accounted for roughly 80 per cent of all deaths and 60 per cent of all terrorist attacks, and many of the immigrants flooding the Middle East and Europe.

The Iceland Social Progress Index, which measures the multiple dimensions of social progress, benchmarking success, and catalyzing human wellbeing, places Afghanistan at third worst among 133 countries for which this index is calculated. Only Chad and the Central African Republic are ranked worse.

Despite the huge amount of aid that the country has received over the last 13 years, Afghanistan has not been able to improve relative to other countries that have received little aid. Both the HDI and the World Bank Doing Business Index 2016 continue to rank Afghanistan in the bottom 10 per cent of all countries.

Case studies on UN multidisciplinary operations

A number of books and edited volumes have presented case studies on the political, security, and/or social aspects of the transition to peace in the 21 countries in the sample, shown in Table 6.3. Table 6.4 shows those case studies that focus on or at least touch upon the much neglected economic aspect of such transition. Some of the latter, however, mostly treat economic reconstruction as if it were development as usual, or simply address a few specific issues (mostly on infrastructure and services rehabilitation or DDR programs).

Table 6.3 Case studies covering security, political, and/or social transitions in war-torn countries

.jpg)

Sources:

1. Crocker, Chester A., Fen O. Hampson, and Pamela Aall (eds), Herding cats: Multiparty Mediation in a Complex World (Washington, DC: United States Institute for Peace Press,1999).

2. Cousens, E.M. and Chetan K. (eds), Peacebuilding as Politics: Cultivating Peace in Fragile Societies (Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2001).

3. Stephen J. Stedman, Donald Rothchild, and Elizabeth M. Cousens, Ending Civil Wars: The Implementation of Peace Agreements (Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner, 2002).

4. Jennifer Milliken, State Failure, Collapse and Reconstruction (Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2003).

5. David M. Malone, The UN Security Council: From the Cold War to the 21st Century (Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner, 2004).

6. Orr, Robert C. (ed.), Winning the Peace: An American Strategy for Post-Conflict Reconstruction (Washington, DC: The CSIS Press, Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2004).

7. Roland Paris, At War’s End: Building Peace After Civil Conflict (Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 2004).

8. William J. Durch (ed.), Twenty-First-Century Peace Operations (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace, 2006).

9. Mats Berdal and Spyros Economides, United Nations Interventionism: 1991–2004 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

10. Charles T. Call (ed.), Building States to Build Peace (Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2008).

11. Michael Pugh, Neil Cooper and Mandy Turner Whose Peace? Critical Perspectives on the Political Economy of Peacebuilding (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008).

12. Jeroen de Zeeuw (ed.), From Soldiers to Politicians: Transforming Rebel Movements After Civil War (Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2008).

13. Mats Berdal and Dominik Zaum (eds) Political Economy of Statebuilding: Power After Peace (Abingdon: Routledge, 2013).

14. von Einsiedel, Sebastian, David M. Malone, and Bruno Stagno Ugarte, The UN Security Council in the 21st Century (New York: International Peace Institute, 2015).

15. Cedric de Coning and Eli Stamnes, eds, UN Peacebuilding Architecture (London: Routledge, 2016).

.jpg)

Sources:

1. Michael W. Doyle, Ian Johnstone, and Robert C. Orr (eds), Keeping the Peace: Multidimensional UN Operations in Cambodia and El Salvador (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

2. Tony Addison (eds.) From Conflict to Recovery in Africa (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003).

3. James Dobbins et al., America’s Role in Nation Building: From Germany to Iraq (Washington, DC: Rand, 2003).

4. James Dobbins, et al. UN’s Role in Nation Building: From the Congo to Iraq (Washington, DC: Rand, 2005).

5. James K. Boyce and Madalene O’Donnell (eds), Peace and the Public Purse: Economic Policies for Postwar State-Building (Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2007).

6. Graciana del Castillo, Rebuilding War-Torn States: The Challenge of Post-Conflict Reconstruction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

7. Arnim Langer and Graham K. Brown, eds. Building Sustainable Peace: Timing and Sequencing of Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Peacebuilding (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

These case studies are recommended for anyone interested in understanding the challenges, the policy constraints, and the lack of operational capacity at the UN to deal with the multidisciplinary aspects of peacebuilding. They will help the reader to understand why major changes are necessary if the UN record is to improve.

Conclusions

It is unfortunate that the UN does not keep a record of its multidisciplinary operations and their cost-effectiveness in supporting countries in their transition to peace, stability, and prosperity. The record we have compiled in this chapter will hopefully provide Secretary-General Guterres with evidence that the operational capacity of the organization needs to change in fundamental ways if he wants to improve UN peacebuilding capacity, both pre-emptively and post-conflict.

Two other points are worth mentioning. In analyzing the record, one should remember that countries in which the UN sets up peacekeeping and peacebuilding operations are generally countries in crisis, just as when countries request a program from the IMF. So blaming the institutions for the crises is not the issue. The issue is whether these institutions can and have indeed helped the countries to come out of the crisis in a cost-effective way or not.

The second issue is that some countries in particular, notably the United States, just like the UN, have neglected economic reconstruction, the economics of peace, as a key ingredient and determinant of a successful transition to peace, stability, and prosperity. The silo approach to issues of security and development which was followed by both the UN and the United States does not help the transition, as the case of Afghanistan well illustrates.

Chapter 7 will focus on some of the economic problems that have affected the record of the past quarter of a century and that need to be addressed if the UN record with peacebuilding and development is to improve going forward.

Notes

1 UN, In Larger Freedom, 31.

2 UN, A More Secure World, 70.

3 World Bank, Breaking the Conflict Trap, 7. Collier has revised this figure in later publications.

4 Email exchanges with Henk-Jan Brinkman of the Support Office and Gert Rosenthal, who chaired the group of experts. The group of experts used data from the World Bank.

5 Most were peacekeeping operations but some were not. Some also transformed from peacekeeping into peacebuilding or integrated operations.

6 This section relies on statistical work done for the United Nations University, WIDER which has been updated for this book. See del Castillo, “The Economics of Peace in War-Torn Countries.”

7 Both UCDP-PRIO data and UN information from the operations were used to determine whether countries relapsed into conflict (the former does not include Timor Leste or Kosovo). This figure may seem outrageously high. It is interesting to note that, with a totally different set of countries and timeframe, Doyle and Sambanis found that from 124 peacebuilding initiatives from 1945 to 1997, 57 percent of the initiatives failed since they could not find a minimum (or negative) measure of peace (absence of violence). If they applied a stricter version of peace which also required a minimum standard of democratization, then the failure rate increased to 65 percent. See Doyle and Sambanis, “International Peacebuilding: A Theoretical and Quantitative Analysis,” American Political Science Review, 94/4 (2000): 779-801.

8 Doyle and Sambanis, Making War and Building Peace, 91.

9 Cousens, introduction, 23.

10 The different indices can be found online by name.

11 Some but not all could be included in Table 6.1.

12 The five worst are (in order) South Sudan, Iraq, Afghanistan, Somalia, and the Central African Republic. The other two are Syria and Yemen.

13 It assesses country risk regarding money laundering and financing of terrorism, taking into account financial and public sector transparency and judicial strength.

14 Del Castillo, Guilty Party, 397–400.