Three

AGRICULTURE

Around 1922, Richard Whitney purchased the bankrupt Zellwood Farms Company along with its several thousand acres of muck land. It was renamed Zellwood Humus Company in 1925. The company mined peat, dried it, and sold it to gardeners and nurseries. In 1933, it began to make a profit, but in 1935, Whitney was accused of embezzlement; he admitted his guilt. The company tried to recover but was unsuccessful. (OC.)

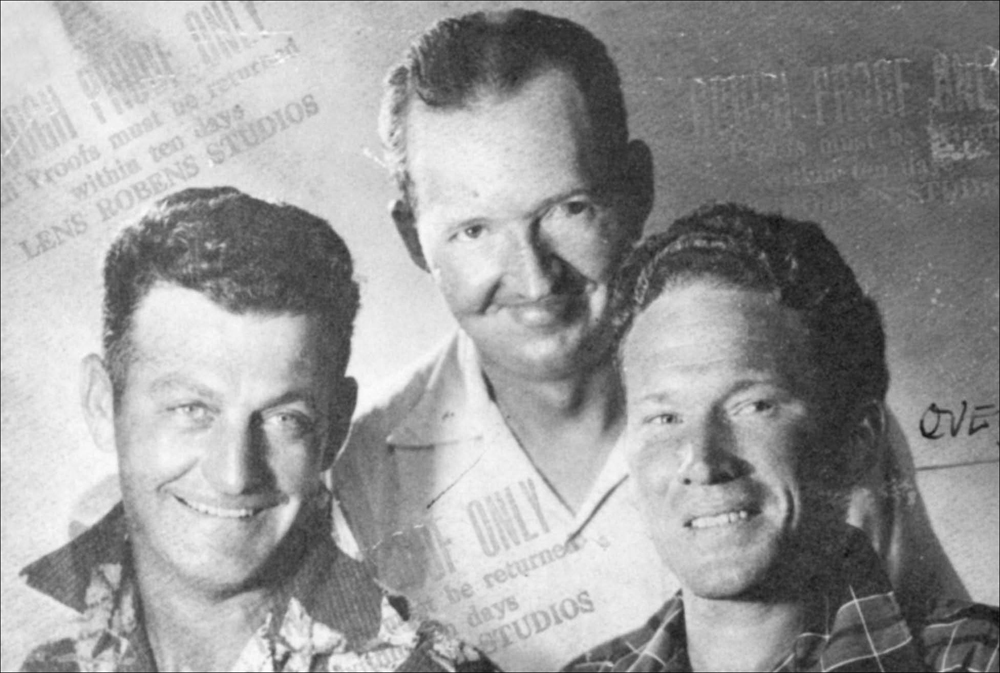

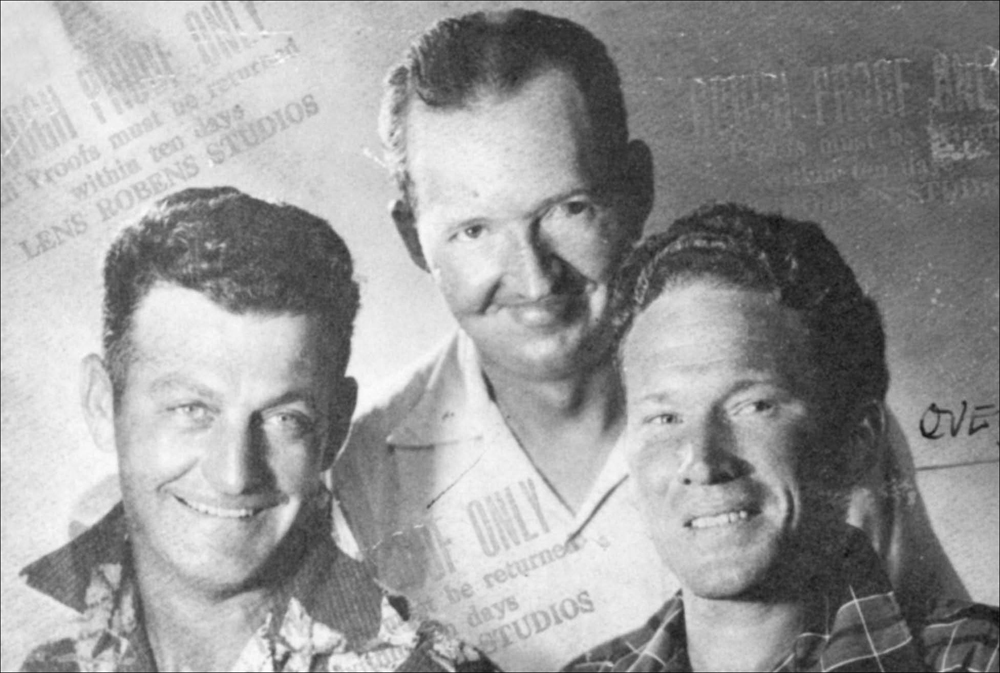

The crop dusters shown here are Johnny Gardner (left), Robert Carroll Potter (center), and Francis “Red” Turner. Potter and Gardner owned the Airplane Dusting Service until the early 1960s, when that business ceased to exist. Potter stayed in the crop dusting business and operated Potter Flyers Incorporated at Zellwood until the State of Florida bought the farmland in the Zellwood Drainage District over a period of years in the late 1990s. (Courtesy of Jan Potter.)

This Stearman biplane was designed by Boeing Aircraft Company in the late 1930s to be used for training pilots in World War II. After the war, Stearmans were adapted for crop dusting. Robert Carroll Potter converted many biplanes into crop dusters, as shown in this image. The smokestack of the Zellwood Dehydration Plant is visible in the background. (Courtesy of Jan Potter.)

Bernard L. “Bob” Hughes is pictured above holding his son, Terry. Bob started crop dusting around Belle Glade in 1947 and, for a time, flew in both South Florida and Zellwood. In 1949, Bob moved to Zellwood. His father, Lawrence “Pop” Hughes (also a crop duster) soon followed. Bob and his brother Paul Edward Hughes leased McDonald airport, near Highway 441, from Marion McDonald and built a hangar. Paul piloted the Stearman pictured below. Elsewhere, west of Highway 441 on Jones Avenue, Pop established his own grass runway and built a house beside what was later called Bob White Field. In 1952, Bob Hughes was killed when his Stearman crop duster and Jerry Svrlinga’s plane collided. Svrlinga was pulled from his plane by W.A. Keen. (Both, courtesy of the Hughes family.)

In this 1999 image, Jan Charles Potter, flying a Piper Brave PA-36-375, sprays sweet corn at Potter Farms in Zellwood. Spring corn was sprayed about 20 times to prevent armyworms from destroying the crop. Each fall, the corn required about 40 applications of pesticides. The Potters were Piper Aircraft dealers who helped Piper flight-test these airplanes. (Courtesy of Jan Potter.)

Emery Rice (left), Clare Roach (center), and Johnny Gardner pose with an alligator in this c. 1940 photograph. After crop dusters noticed the gator from the air, the sizeable reptile was removed to protect the safety of field workers. (Courtesy of Diana Rice Acree.)

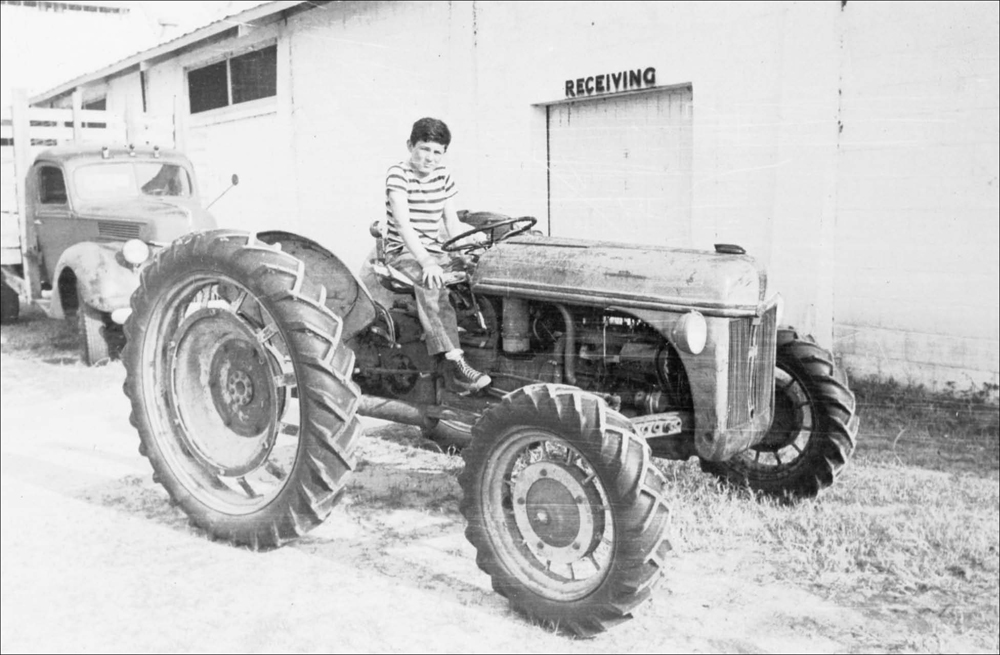

Emery and Gladys Rice came to Zellwood from Indiana in 1945. The government sent Emery to Florida to run the Zellwood Dehydration Plant (visible in the background at right in the above image). After World War II ended, rations—such as dehydrated carrots and potatoes—were no longer necessary, so Emery, who had farmed from the start, raised corn to feed his cattle. Emery and Gladys’s daughters, Ella Mae and Diana, are pictured above, and Emery and Gladys’s son, Lynn, is pictured below on a tractor at the plant. (Both, courtesy of Diana Rice Acree.)

In the late 1940s, Perl Stutzman came from Ohio to Zellwood to farm; he devised the spray rig shown in the above image. Pictured below are Laura and Sanford Stutzman, Perl’s parents, with a truckload of Zellwood corn. According to the July 4, 1948, edition of the Orlando Morning Sentinel, the Stutzmans received more for their corn per crate because it was of a higher quality; their 320 acres yielded $31,735 worth of corn sales in two days on the New York market. (Both, courtesy of Cletus Stutzman.)

In 1949, farmer Charles Grinnell Sr. photographed his 1929 Model A Ford carrying the morning’s harvest of radishes picked by Ira Whatley (left), Cecil Jones (center), and J.C. Love (sitting on fender). Later in the day, the same crew washed the bunched radishes, packed them in wire-bound crates, and stacked them in a cold room to await transport to market. (CG.)

By 1981, Grinnell Farms’ custom-made 10-row harvester could pick the equivalent of a 1949 half-truckload of radishes (shown in the previous image) in under 10 minutes. The harvester efficiently pulled radishes, cut off their leaves, and put them into wagons. Charles Grinnell Jr., pictured here on the harvester, assumed leadership at Grinnell Farms upon his father’s retirement in 1984. (CG.)

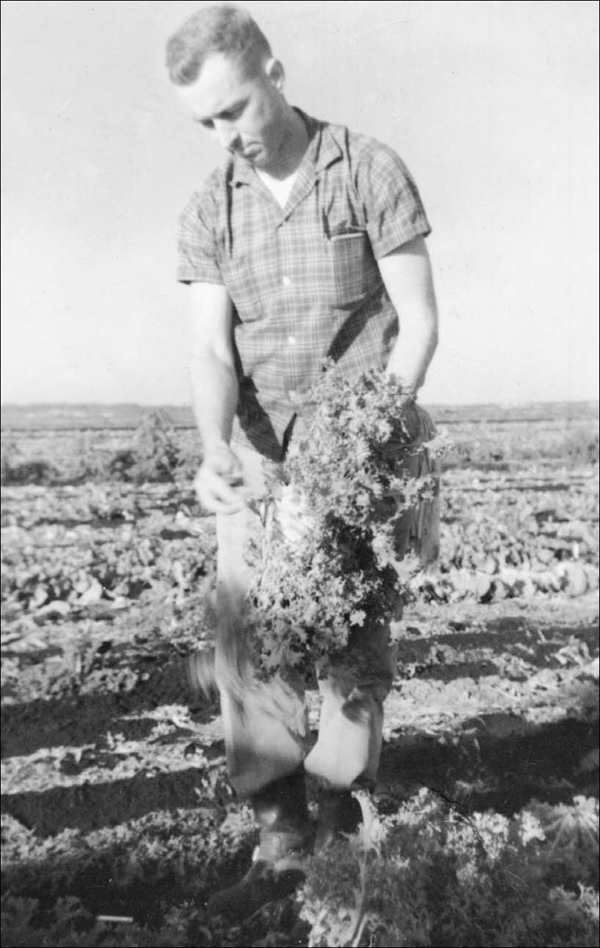

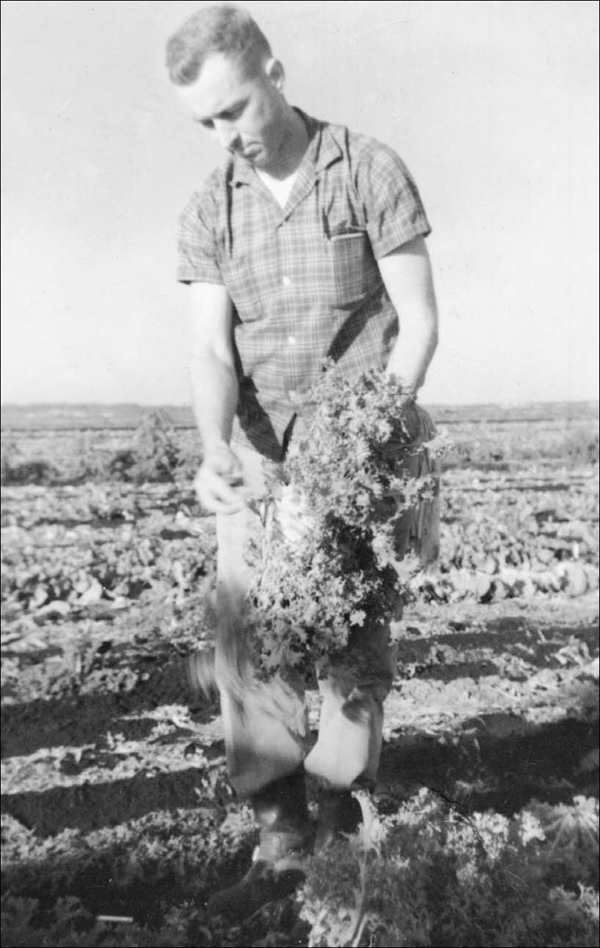

In this 1960s photograph, Walter A. Duda inspects a leaf lettuce crop on the A. Duda & Sons, Inc., Zellwood farm. A third-generation member of the Andrew Duda family, Walter had an inherent love of farming and held a bachelor of science degree in agriculture from the University of Florida. In 1997, he was appointed president of Duda’s farm division, which, by then, had operations in four states. He died in 1999 at age 63. (Courtesy of A. Duda & Sons, Inc.)

In 1946, the Duda brothers—John, Andrew, and Ferdinand—purchased several Tillavators (tilling machines manufactured in Wisconsin) that were well suited for the muck soils on their Zellwood farm. Along with their father, Andrew, the three brothers began their farming enterprise in Slavia, Florida, in 1926. The Zellwood farm provided a lengthened season for vegetable crops. This photograph was taken in the 1960s. (Courtesy of A. Duda & Sons, Inc.)

This 1980s image shows the A. Duda & Sons Zellwood farm from the air. The primary crops grown on the approximately 3,400-acre farm included carrots, celery, sweet corn, cabbage, and leaf items such as lettuce and parsley. Over its 50-plus-year history, the farm produced an estimated 80 to 100 million packages of vegetables. The farm began producing sod in 1980. (Courtesy of A. Duda & Sons, Inc.)

Dennis Robinson (left) began working on the A. Duda & Sons farm in 1948, retiring as its general manager in 1989. With him in this 1960s photograph is J.W. Fortson, who worked as a crop superintendent at the farm. Vernon “Buddy” Robinson (no relation to Dennis), who transferred to the Zellwood farm from the company’s Belle Glade location in 1966, managed the farm until it was sold to the State of Florida in 1999. (Courtesy of A. Duda & Sons, Inc.)

Kenneth F. Jorgensen, a Cornell University graduate in agricultural economics, worked for Beech-Nut Packing Company in New York. In 1944, Beech-Nut’s baby food and C-ration business transferred Jorgensen so that he could supervise its new Zellwood farm. Plagued by equipment shortages (due to the war), hurricanes, and insects, Beech-Nut sold the farm to Jorgensen, Bob Stewart, and Frank Dutton in 1946; that year, the men started Zellwin Farms Company with 600 acres. (Courtesy of Florida Fruit and Vegetable Association.)

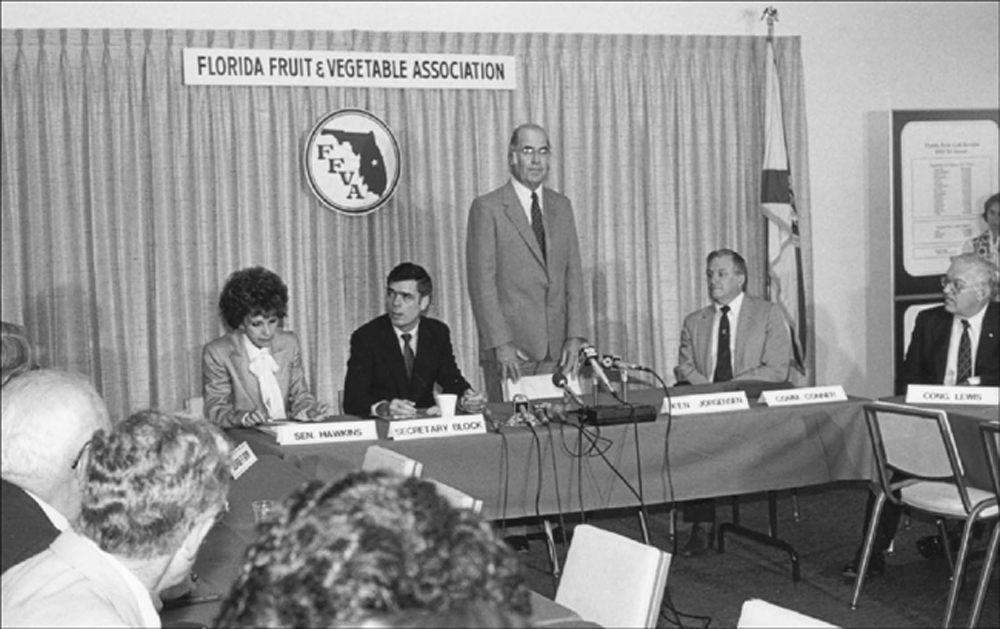

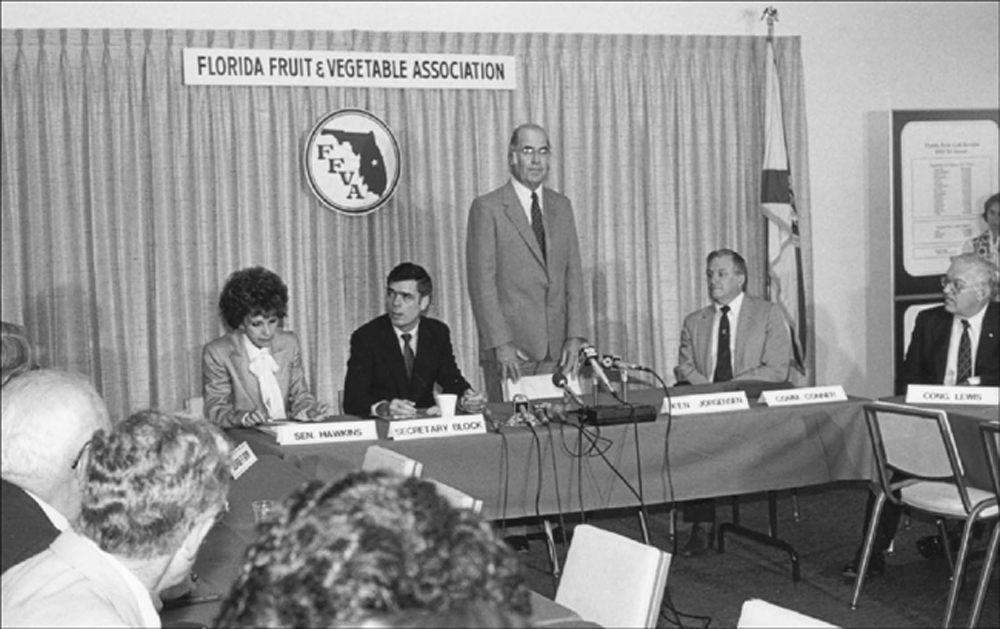

Kenneth Jorgensen’s influence went beyond being dean of Zellwood’s muck. From 1983 to 1985, he was president of the Florida Fruit and Vegetable Association. He toured internationally as agricultural advisor with Florida’s then-secretary of agriculture, Doyle Connor. Jorgensen (standing) died in 1998, as Zellwin Farms was transitioning after the state’s buyout of the farm. He was posthumously inducted into the Florida Agricultural Hall of Fame in 1999. (Courtesy of Kathy Youngs.)

Zellwin Farms Company devoted the majority of its fields to growing carrots, corn, and radishes. It also grew escarole, chicory, romaine, Boston and Bibb lettuces, broccoli, cauliflower, watercress, beets, coriander, and several varieties of cabbage. Carrot harvesting machines (above) pulled carrots out of the ground and clipped the tops. Trucks took carrots to the packinghouse (below), where they were washed, sized, and graded before being automatically packed into 1-, 2-, 5-, or 50-pound bags. The carrots primarily went to the Eastern United States, though they were exported to Toronto and Montreal in winter months. Zellwin marketed its own produce and used independent truckers for delivery. (Both, courtesy of Glenn Rogers.)

Carrying on the famous Zellwood sweet corn tradition that started many years ago, the Scott family at Long & Scott Farms continues to grow the only “Zellwood Sweet Corn.” They have updated their corn label, but the outstanding taste is still the same. In 1997, Long & Scott Farms built their first pole barn to house Scott’s Country Market, which offered corn and a variety of seasonal produce. (Courtesy of Rebecca Scott Ryan.)

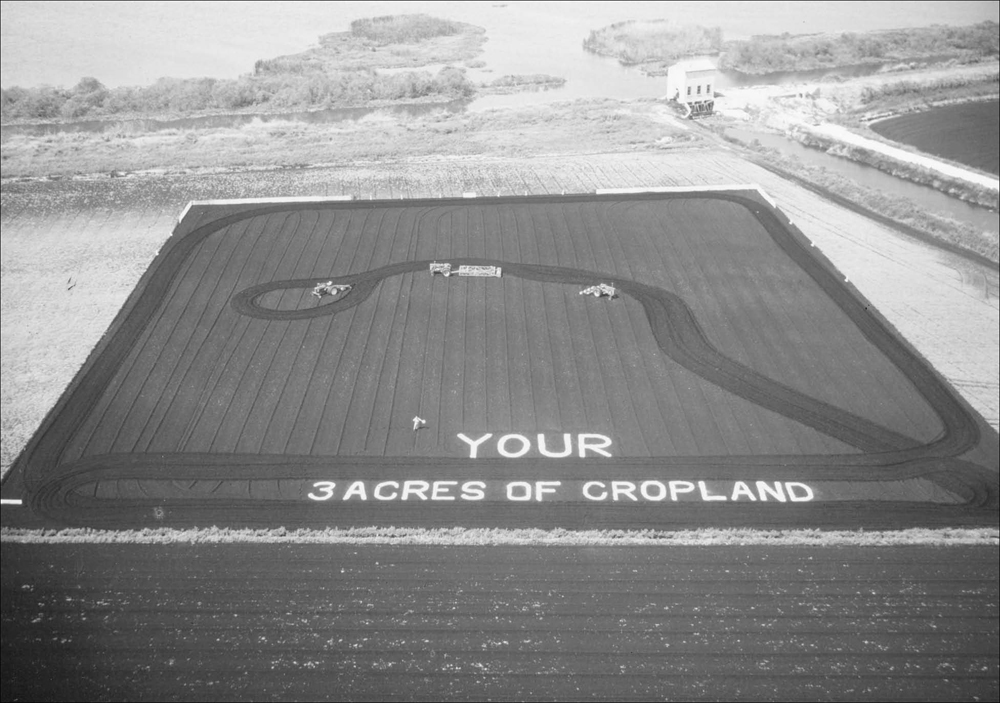

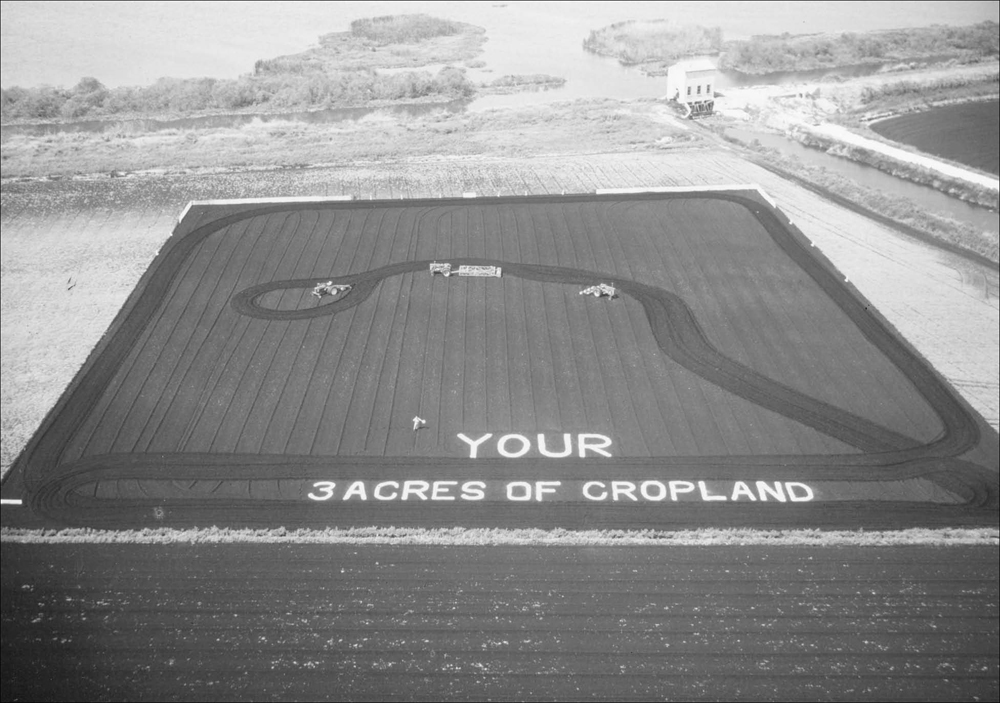

In 1957, Henry Swanson was an agricultural agent for Orange County. The county’s yield ranked second in Florida and twenty-first in the United States. Swanson proposed using a photograph to illustrate that three acres of farmland would feed one person for a year. Billy Long obliged Swanson by plowing three acres of muck, stamping words into the muck with his boots, and filling the words with lime. Long is standing left of the “Y” to give perspective. (Courtesy of Billy Long.)

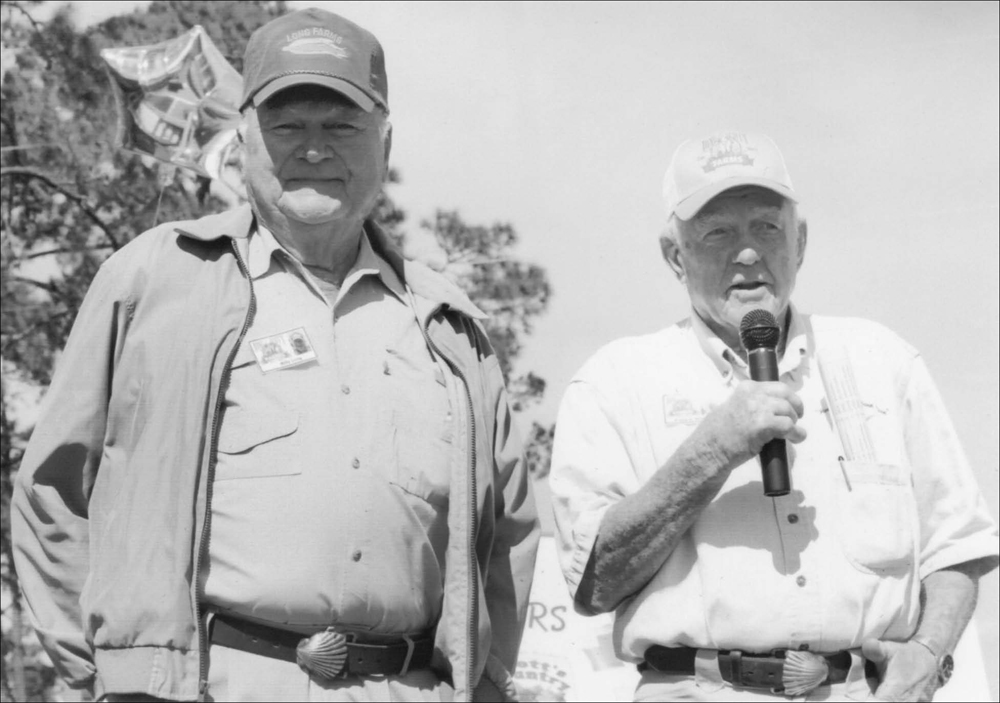

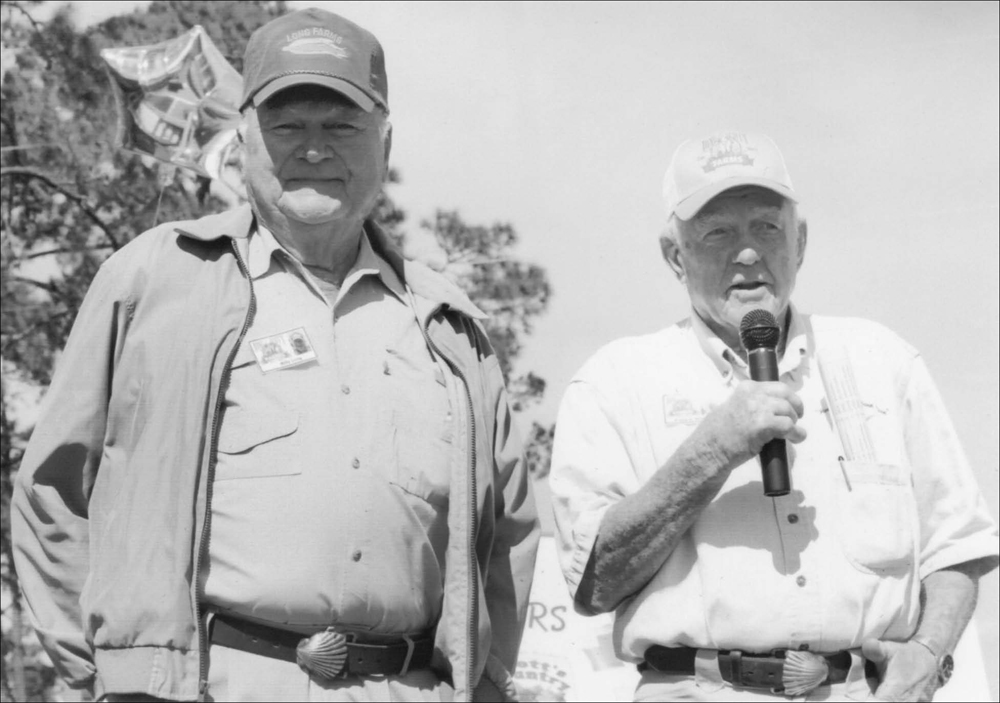

In 1963, Frank Scott (right), who had farmed in Virginia, joined Billy Long (left), a longtime friend, to create Long & Scott Farms. Long had started farming on the Zellwood muck in 1952. They combined efforts to clear the sandy land west of the muck, where Long & Scott Farms is today. This photograph was taken at Long & Scott Farms’ 50th anniversary. (Courtesy of Billy Long.)

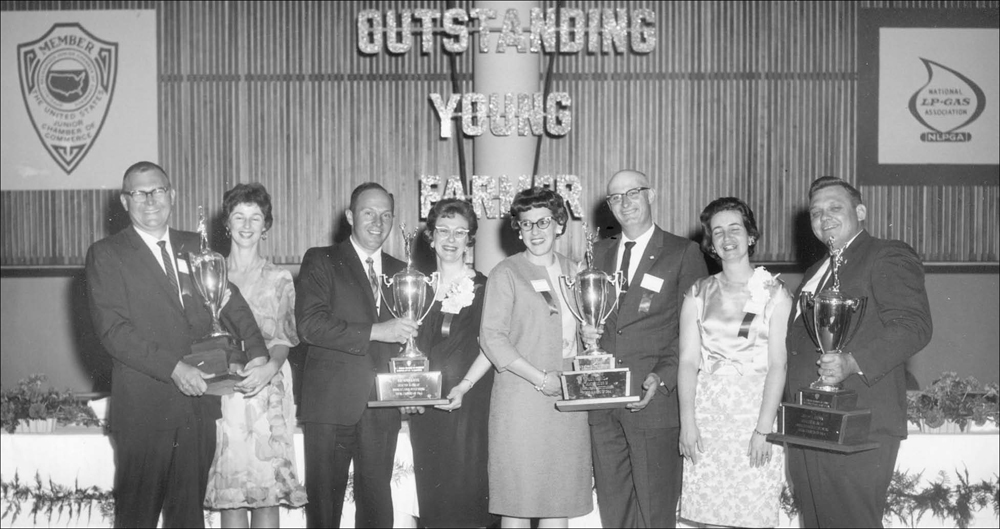

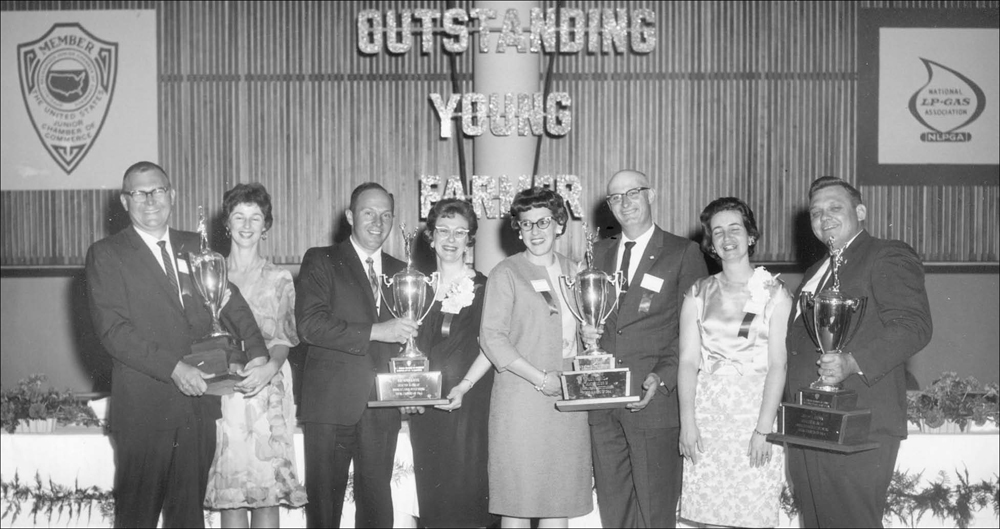

In 1965, Billy Long (far left) and his wife, Bobbie (second from left), flew to Fort Collins, Colorado, where Billy was named an Outstanding Young Farmer. The Jaycees sponsored the event, in which counties selected candidates. From those, each state submitted an entrant to compete at the national level. Billy Long’s farming successes were recognized again when he was inducted into the Florida Agricultural Hall of Fame in 2005. (Courtesy of Billy Long.)

Around 1951, four Ohio farmers, including Franklyn Gaede (pictured), heard about the rich farmland in Zellwood. They bought 240 acres of muck land and leased 160 more acres. Their Ohio Farmers company owned 400 acres in Michigan, and the owners purchased trucks to haul the vegetables to Ohio, where they were packaged. At first, these farmers grew all kinds of vegetables. Later, crops were restricted to mainly radishes, along with some carrots and sweet corn. (Courtesy of Orlan and Connie Wichman.)

This image shows carrots being harvested under cloudy skies in the spring of 1998 at Stroup Farms, Inc. Dan Stroup began farming in Zellwood in 1957. Dan’s son, Scott—and then Scott’s son, Christopher (shown here pulling the wagon to collect the family’s final carrot crop)—followed in his footsteps, carrying on the family farming tradition until 1998, when the Stroup farmland was bought by the State of Florida, as were most of the farms within the Zellwood Drainage District. Stroup Farms also grew corn, broccoli, and assorted greens. (Courtesy of Lillian Stroup.)

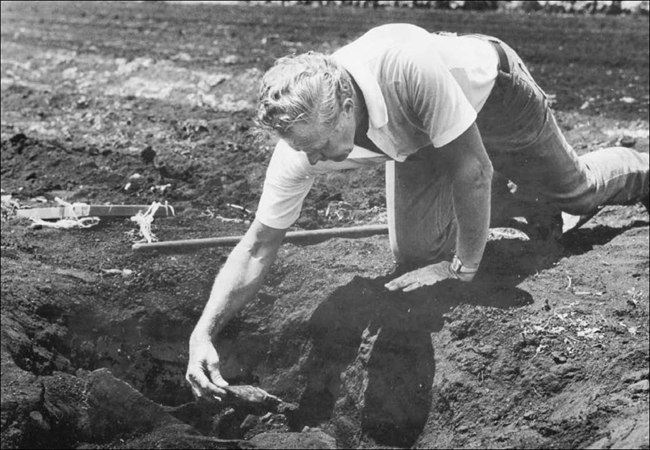

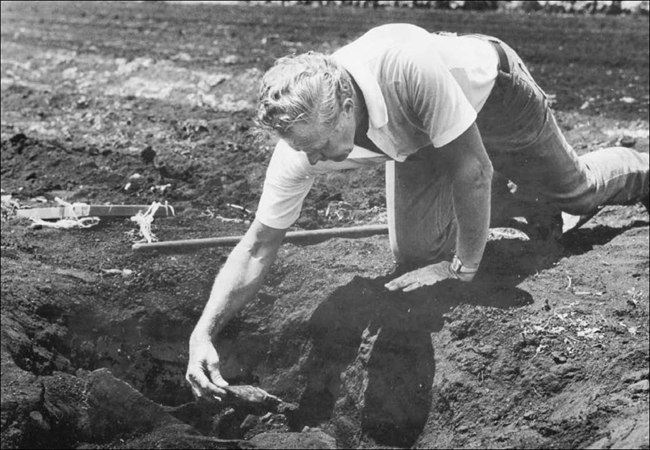

Farmers discovered numerous aboriginal dugouts on farms around Lake Apopka. In 1978, after plowing a radish field, the Grinnell family noticed chunks of charred wood. The Orlando Science Center sent Art Dreves (pictured) to investigate. He located a dugout estimated to be around 1,200 years old. Extremely heavy, waterlogged, and friable, it could not be moved without being destroyed. (Courtesy of the Orlando Sentinel.)

Mule trains were specially constructed for hand-harvesting and hand-packing sweet corn. The crates, which each held about 50 ears of corn, were assembled on top of the machine and then slid down chutes to the packing area. Pickers walked down the rows in front of the machine, placing ears in bins. Using this system, a crew could harvest 25 rows at a time. Once the corn was packed, the crates were stacked on a six-wheel flatbed truck. This truck was pulled through the field by the mule train, then unhooked when full (about 1,000 crates.) The corn was driven to a pre-cooler for hydro-cooling to about 36 degrees Fahrenheit. Refrigerated trucks delivered the corn all over the United States. (Courtesy of Jan Potter.)

This map shows farms that were bought by the state in the late 1990s; the map also notes the previous landowners. The map shows Lake Apopka’s North Shore Restoration Area (NSRA) within Orange and Lake Counties. The NSRA includes the land along the Zellwood side of Lake Apopka that had formerly been Duda farms, Zellwood Drainage District, and the Sand Farm. (Courtesy of James Peterson and St. Johns River Water Management District.)

In 1958, Ted Pope and Billy Long modeled Zellwood’s Muck Suppers after Sanford farmers’ Perishable Tramps. The so-called Zellwood Country Club, named by Tom Staley, served as the venue for the monthly suppers where farmers could socialize. This 1998 photograph shows the last meeting at the Zellwood Country Club. Sand Suppers at Long & Scott Farms carried on the tradition after the state’s buyout of much of the land surrounding Lake Apopka. (Courtesy of Glenn Rogers.)

W.B. and Louise Shiver were Zellwood entrepreneurs from 1954 to 1981. The family homesteaded a strip between the railroad tracks and Highway 441, where they sold corn, tomatoes, and locally grown produce. Louise was a Cub Scout leader, and W.B. was the volunteer fire department commissioner. The couple is pictured at right; Louise is pictured below. (Both, courtesy of Deneth Shiver.)

The Sydonie dairy’s herd of Jersey cows was under the care of head dairyman William White from Tennessee. The Sydonie dairy provided milk delivery to northwest Orange County until about 1925. According to Florida historian Jerrell H. Shofner, White bought T.J. King’s dairy herd in 1926 and then sold milk directly to consumers.

Emery Rice stored dried corn in his granaries located south of Jones Avenue and half a mile west of Highway 441. In his airtight silos, Rice kept green fodder (silage or chopped corn stalks) used for feeding livestock in the winter. (Courtesy of Marion Rice.)

Originally from Scotland, William Edwards and his wife, Isobel, lived in the former T. Ellwood Zell home. Isobel organized Zellwood’s first Girl Scout troop. William managed both Laughlin and Pirie Estates. He served as governor of Orlando General Hospital and as president of Florida Citrus Exchange, Plymouth Citrus Growers Association, Bank of Apopka, and the Orange County Chamber of Commerce. (Courtesy of Orange County Regional History Center.)

In this 1973 aerial photograph, the building for Lester B. Vincent and Son Florists is at far left. Directly behind the flower shop is the home of Lester and Clarice Vincent. The ranch-style home of Reasley Vincent Jr. and his wife, Dudley, is slightly above center. The 14 or so white edifices throughout are the greenhouses of Lester, Reasley Sr., and Reasley Jr. Ponkan Road is at the top of the image. Highway 441 slants from upper left to lower right, with railroad tracks running parallel to 441 along the bottom of the picture. Note the numerous orange groves, which were vital to the area’s economy at the time. (Courtesy of Becky Vincent Juvinall.)

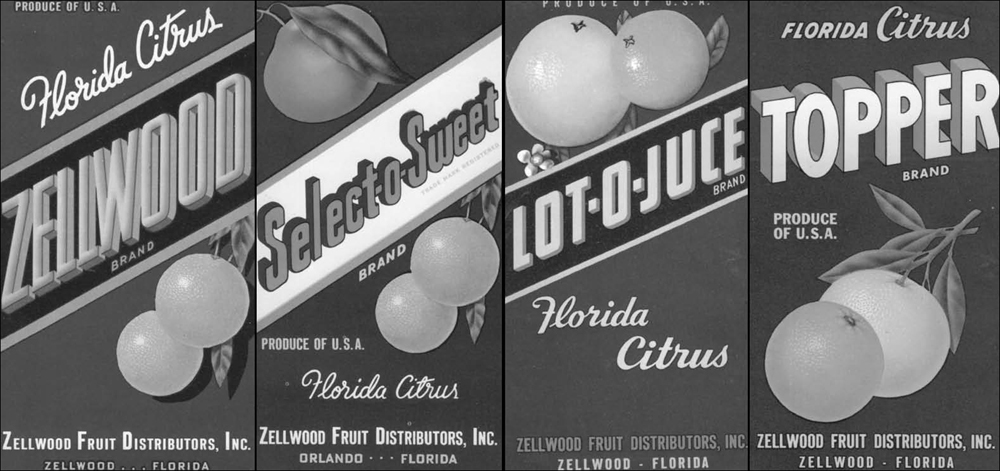

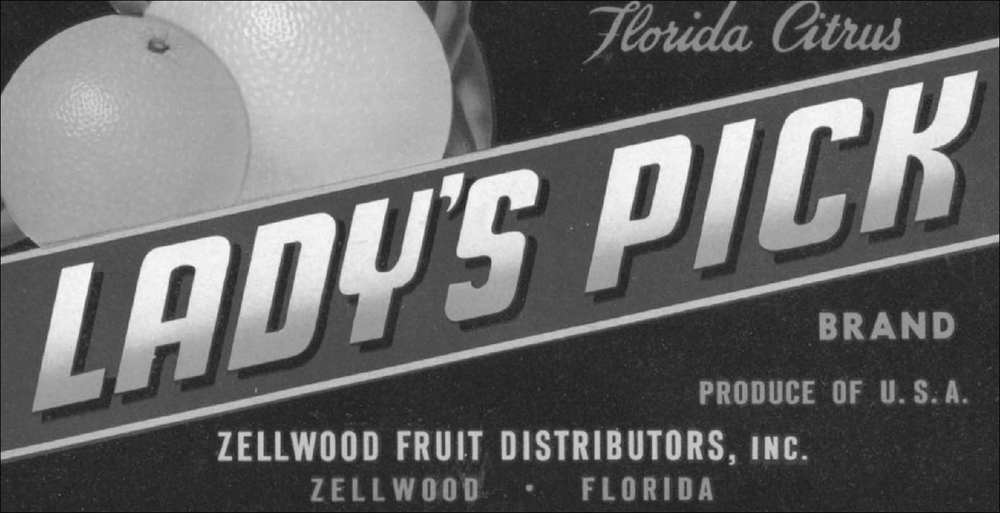

Ralph Meitin and Myer Shader founded Zellwood Fruit Distributors in 1943. The company employed approximately 130 people. This 1952 company photograph does not include truck drivers or citrus pickers. The packinghouse, located by the railroad tracks near Highway 441 and Ponkan Road, burned down in March 1960. (Courtesy of Jon Miller.)

Plymouth Citrus Growers Association, affiliated with the Florida Citrus Exchange, was organized in 1910. The group rented a packinghouse on Highway 441 and purchased it in 1911. William Edwards, from Zellwood, served as president of the association for 20 years. He was succeeded by E.W. Fly. The association employed many Zellwood residents. In the peak season, employees worked from early morning until 9:00 or 11:00 each night. The work was very laborious. (Courtesy of Deloris Lynch.)

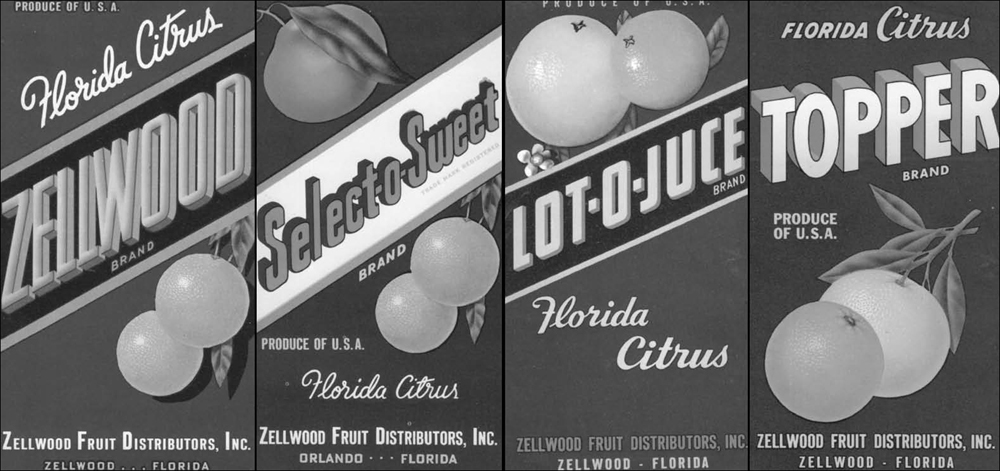

Citrus was shipped under various labels from Zellwood Fruit Distributors. It went by railroad to the Northeast and Midwest and by truck to Atlanta and Columbia, South Carolina. “Fruit was the currency of Central Florida,” wrote Isabel Wilkerson in The Warmth of Other Suns. (All images courtesy of Julian Meitin.)

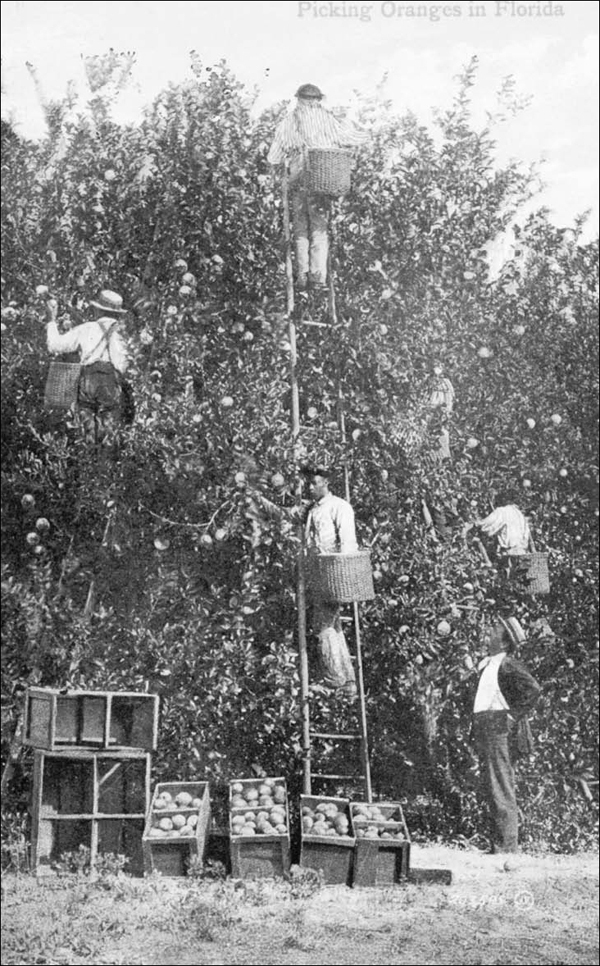

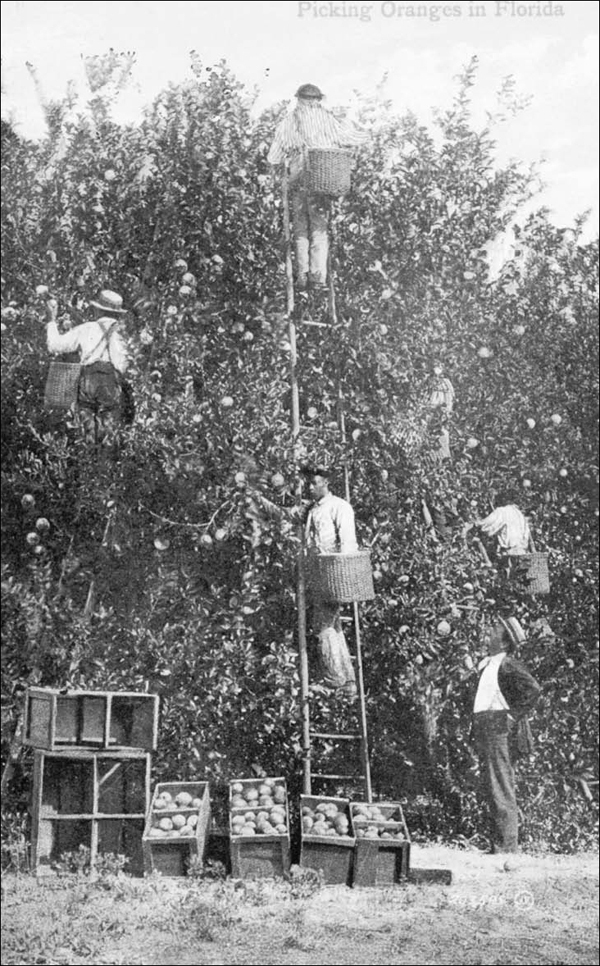

These postcards show African Americans picking oranges. Pickers in Zellwood were employed by Libbey; Miller, Meitin, and Shader; Zellwood Fruit Distributors; Coen; Svrlinga Groves; and others. Pickers climbed 20- to 30-foot ladders with canvas bags strapped over their shoulders. The bags, which could hold 50 pounds of oranges, had a clip-style opening, allowing workers to empty the fruit from the bag into a box. Approximately 500 boxes, each holding 90 pounds of produce, could be harvested from an acre of orange trees. With one worker picking 10 boxes of oranges per hour, an acre would take 50 hours of harvest labor. As grove equipment evolved, pruning machines trimmed trees so that workers could pick from shorter ladders, and large, round bins replaced the wooden boxes. (Both, JFB.)

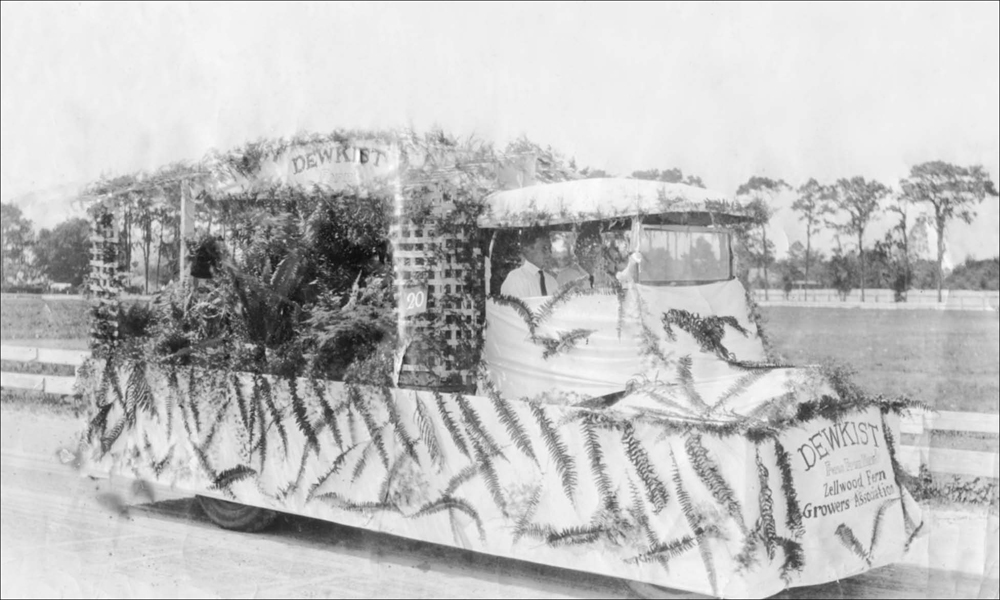

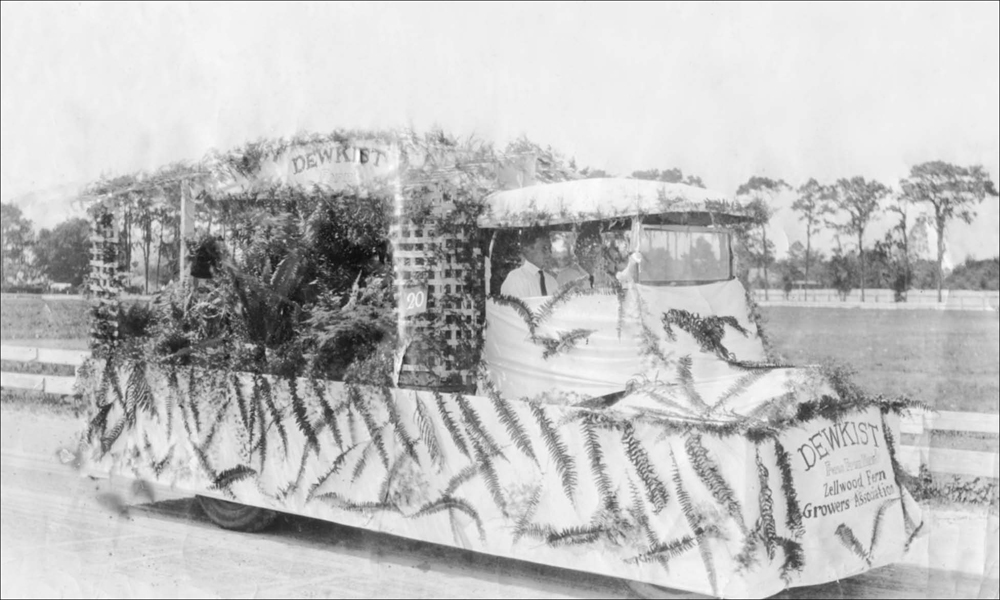

This float represented Dewkist, a trademark of Zellwood Fern Growers’ Association, organized in 1922. The association shipped 285,000 ferns in the spring of the following year. During the 1925–1926 season, 850,000 ferns were shipped by this association, which marketed Asparagus plumosus and Asparagus densiflorus throughout the United States and parts of Canada. (Courtesy of Mary Wright.)

The azaleas outside of Reasley Vincent Jr.’s greenhouse exemplified the many beautiful flowers, plants, and ferns that he grew commercially. His father, Reasley Vincent Sr., was well known for his innovative propagation and development of new types and color combinations of violets and orchids. (Courtesy of Kathy Parker Rice.)

Jessie Hargroves (with a mule named Lightning) plows walkways between ferns at Marsell’s Fernery. Anne and Elmer Marsell started their business in 1924, growing ferns on Round Lake Road. Their leatherleaf ferns were grown under slat sheds. At peak times, 50 to 60 workers cut ferns. Cutters were wary of snakes, and in 1956, a black panther was said to frequent the sheds at night. (Courtesy of Laurie Marsell.)

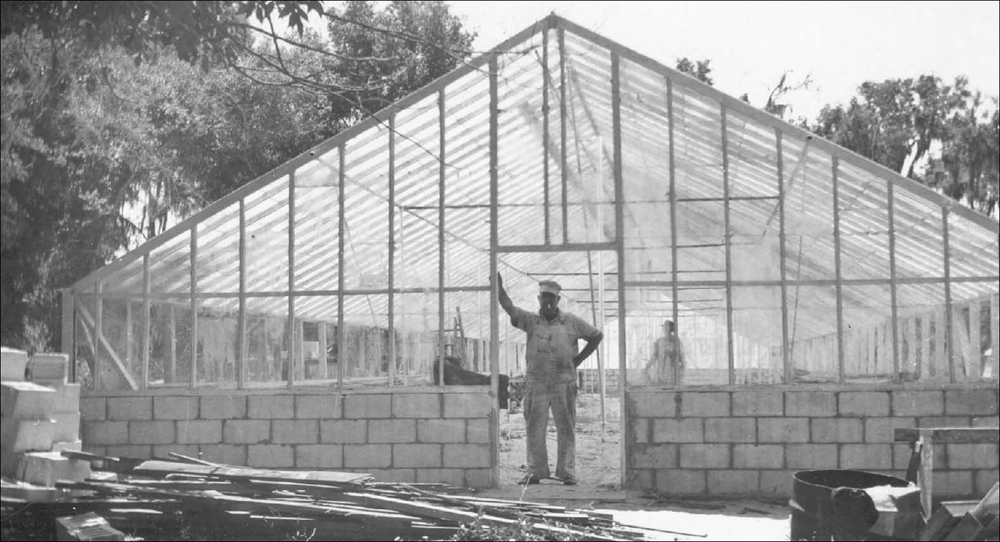

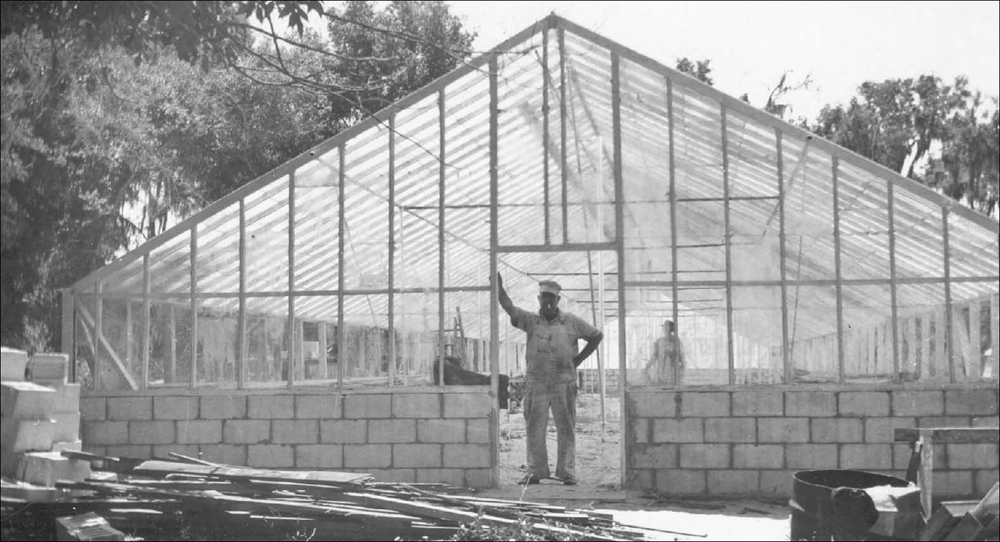

Allen Sewell stands in one of the first glass greenhouses in Zellwood. E.W. Fly bought and shipped the glass from the north. Sewell served as the foreman at Fernwood Nursery for over 15 years. During that time, Fernwood grew philodendron and sansevieria plants. It was hot and humid in the greenhouses—uncomfortable for workers, but exactly what the plants needed to thrive. (Courtesy of Louise Roberts.)

A group of Fernwood workers poses in the above 1940s photograph. E.W. “Walter” Fly started Fernwood Nursery in the 1930s at the end of Wesley Road. Originally, the nursery grew Boston ferns outdoors under oaks. Later, the company made sheds with two-by-four posts holding up slats; spacers let sunlight through. The nursery shipped cut ferns to florists. Workers lit smudge pots, spaced about 30 feet apart, to protect ferns during extremely cold weather. Boilers later replaced the smudge pots; propane gas heaters followed. Plastic sheets kept the heat in the sheds. Walter’s son, Edwin Fly, graduated from the University of Florida, served in World War II, and then worked at Fernwood. In the early 1960s, the women shown below were among those who worked at Fernwood. They are, from left to right, Betty Smith, Lorene Brown, Lula Martin, unidentified, and Gladys Martin. (Above, courtesy of Sue Hazelwood; below, courtesy of Betty Smith Allen.)