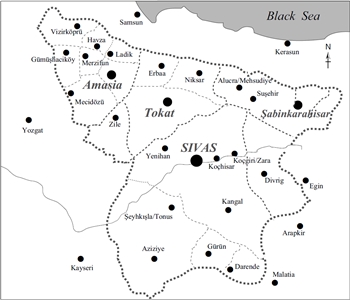

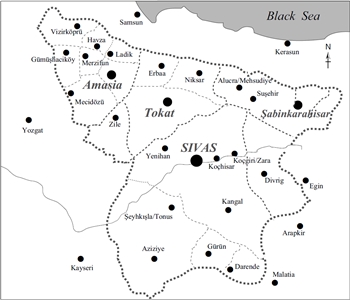

The vast Sıvas vilayet, one of the most densely populated in Asia Minor, had approximately 1 million inhabitants in 1914, including 204,472 Armenians and about 100,000 Greeks and Syriacs. The Armenians in the urban centers were the most conspicuous, but non-negligible numbers of Armenians inhabited the countryside as well; they lived in some 240 villages and hamlets, boasting 198 churches, 21 monasteries, and 204 schools with a total enrolment of 20,599.1 Unlike the vilayets we have examined so far, the Armenians in the Sıvas vilayet lived side-by-side with a Turkish-speaking (rather than Kurdish-speaking) Sunni Muslim population, including 10,000 muhacirs who had settled in the region in the wake of the Balkan War.2

The 30 March 1913 nomination of a new vali, Ahmed Muammer Bey – he held his post until 1 February 19163 – seems to have exacerbated the degradation of the non-Muslims’ situation. In accordance with the wishes of Young Turk circles, as soon as he took office the vali initiated a policy of boycotting Christian entrepreneurs and merchants after the Ottoman defeat at the hands of the Balkan coalition. Muammer, a native of Sıvas and the son of a magistrate, played a decisive role in creating a network of Ittihadist clubs in his native vilayet from 1908 on.4 Thirty-two years old when he assumed his post, the vali was the very prototype of the new sort of man the CUP needed to implement its policy of creating a “national economy” in the provinces: he was simultaneously the vali and the representative of the Unionist Central Committee in this vilayet in the middle of Asia Minor, through which he traveled extensively in order to broaden the circle of Ittihadist party activists and spread party propaganda.5 According to Armenian sources, the real problems began only after the adoption of the reforms in the eastern provinces. Like the Greek populations living on the coasts of the Aegean, the Armenians of the Sıvas vilayet were the victims of the increasingly harsh policies of the Young Turks. In particular, Ahmed Muammer carried out a plan of economic harassment, the objective of which was to put an end to the Armenians’ “prosperity” and bring Turkish cooperatives into existence.6 He even seems to have called on the hojas of the vilayet to give their sermons a corresponding slant.7 This determined vali also created schools in which Armenian teachers trained apprentices.8 He thus sought to eliminate what seemed to him to be an Armenian monopoly over craft production. But Muammer also attacked religious institutions; such as when he confiscated the land belong to the monastery of St. Nshan, located near the city, in order to build a barracks for the Tenth Army Corps on it.9 But the veiled economic boycott imposed by the authorities apparently did not completely ruin the Armenians. In April and May 1914, several suspect fires broke out, one after the next, in the bazaars of Merzifun/Marzevan, Amasia, Sıvas, and Tokat. In Tokat, according to an Armenian middle school teacher, 85 stores, 45 homes, and three khans were reduced to ashes by a fire that raged in Baghdad Cadesi, the street where many of the city’s businesses were located, on 1 May 1914.10 Three big flourmills were also ravaged by fires in Merzifun, Amasia, and Sıvas.11 We have no proof that the local authorities had a hand in these criminal fires, but Armenian circles were not unduly persuaded to believe that the fires had been set on Ahmed Muammer’s initiative. When the general mobilization order, the seferbelik, was announced in Sıvas on 3 August, every male of draftable age went to enroll at the recruitment center that had been set up in the Ulu Cami mosque, formerly the Church of St. Eranos. Over the next few weeks, the Church of the Holy Cross and some of the schools that belonged to the 20,000 Armenians of Sıvas – such as the Aramian middle school or the Sanasarian lycée – were gradually confiscated by the military authorities, who wished to use them as barracks.12 By paying the bedel, some of the Armenian conscripts avoided mobilization or were assigned to the Red Cross. As elsewhere, the Teklif-i Harbiyye provided an opportunity for obvious abuses, to Armenian merchants’ cost: all means of transportation in both the cities and the villages were requisitioned.13 Furthermore, the national Armenian hospital assumed the costs of maintaining 150 hospital beds, which were put at the army’s disposal.14

Among the striking measures observed in Sıvas after the Ottoman Empire entered the war was to dispatch to the Caucasian front the Tenth Army Corps, made up of recruits from the vilayet, including some 15 Armenian doctors and numerous Armenian soldiers.15 In addition, 2,500 worker-soldiers were assigned to two labor battalions. The first improved the road leading from the konak to the stone bridge at Kızılırmak; the second built a pipeline two kilometers long to provide the city with drinking water.16 Sıvas also served as a rear base for the Army of the Caucasus; in particular, the soldiers who fell victim to the dysentery and typhus epidemics decimating the army because of catastrophic sanitary conditions were sent here.17 Once the French Jesuit fathers had left,18 Reverend Ernest Partridge’s American mission was the only foreign institution remaining in Sıvas. The national Armenian hospital and the establishment of the American Red Cross, directed by Dr. Clark, played a major part in fighting the epidemics. Nevertheless, 25,000 epidemic victims were recorded.19

Two events that occurred in the Sıvas vilayet attest to the tension-fraught atmosphere reigning in the regional capital. Since no one held the office of primate in the region, the Armenian Patriarchate had named two auxiliary primates to head the dioceses of Sıvas and Erzincan – Bishop Knel Kalemkiarian and Father Sahag Odabashian. In this troubled period, the patriarchate deemed it indispensable to maintain an official presence in these areas, in which the authorities recognized its right to represent the community. On 20 December, the two prelates arrived in Sıvas together. Odabashian, a native of the city, stayed with his family for a few days while waiting to find a vehicle that could take him to his new post. It seems, however, that the Interior Ministry had raised doubts as to the prelate’s real mission. An encrypted telegram that it sent Muammer on 21 December 1914 informed the vali that, “there are serious reasons for thinking that [Odabashian] plans to precipitate disorders among the Armenians” and requested that he “put him under surveillance as soon as he arrives.”20 The task of watching the 38-year-old vicar was entrusted to Halil Bey, the commander of the çete squadrons; Emirpaşaoğlu Hamid, the leader of the Çerkez of Uzunyayla; and the çetes Bacanakoğlu Edhem, Kütükoğlu Hüseyin, and Zaralı Mahir. They assassinated Odabashian on the road between Suşehir and Refahiye, near the village of Ağvanis, on the morning of 1 January 1915.21 The investigation that followed this murder, which had also taken the life of Odabashian’s driver, Arakel Arslanian, offers a striking example of the formalism and duplicity of the administration.22 The initial evidence indicated that “the weapons used were of two different kinds, resembling a Mauser and a Martini”; however, “since weapons of this kind are not just lying around, except in the Armenians’ homes, it is possible that the authors of these murders are Armenians who committed the crime with a particular purpose in mind.”23 The investigation proceeded to focus on the surrounding Armenian and Greek villages, asking how people who had been absent from their village on the day of the murder had “spent their time.”24 The kaymakam of Suşehir, the investigating magistrate, and the commander of the gendarmerie went to the scene of the crime and interrogated witnesses. Thus, it was established that the murder was “committed by two individuals riding gray horses, while the other mounts were of various colors,” that this band was armed with “Mauser Gras and Martini” rifles, and that the individuals in question had spoken Armenian, Greek, and Turkish. Zehni, the judge, observed, “the fact that they had not touched the victim’s seven piasters gold, watch, baggage, or other personal belongings seems to indicate that the motive for the crime was not theft, but that the murderers had some other objective.”25 Suspicion focused on a Greek, Kristaki Effendi, from the village of Alacahan in the kaza of Refahiye, who had been “recognized by his voice”; however, the kaymakam of Suşehir thought that “the guilty parties were Armenians or Greeks from the region of Erzincan.”26 The Armenians of Sıvas understood very well that this “investigation” was a masquerade staged by the authorities to cover up their own role in the murder of the prelate, an event that, under other circumstances, would have caused a commotion. Yet no one dared protest, whether in Constantinople or Sıvas.27 The accusations were, to be sure, so implausible that Muammer felt a need to engage in diversionary tactics. Patriarch Zaven notes in his memoirs that immediately after the murder of Sahag Odabashian, the local authorities accused the Armenians of taking revenge by poisoning the bread delivered to the Turkish soldiers, an accusation that spread through the population, leading to open hostility toward the Armenians.28 On the night of 5/6 January, several soldiers from one of the Kavakyazı barracks had shown signs of indigestion. This “poisoning” was blamed on the bread, in which there were blue streaks, and taken as proof that a suspect substance had been mixed in with the dough. Ahmed Muammer, who went to the barracks without delay, observed that the Armenian soldiers there did not have the same symptoms, and concluded that the Armenians had doubtless committed a crime against the Turkish recruits. The Armenian soldiers were immediately confined to the basement of the barracks, while their Turkish colleagues were put on a state of alert; armed men surrounded Armenian neighborhoods and the authorities told the Turkish populace to get ready to react if the Armenians staged an “insurrection.” In the course of the night, the accused bakers were arrested and tortured in order to make them confess as to which party, the Dashnaks or the Hnchaks, had ordered them to poison the soldiers’ bread.29 In the space of a few hours, Sıvas was transformed into a city under siege; massacres would probably have ensued if Constantinople had not stepped in to prohibit them. The investigation conducted the next day by Haci Hüsni, an army physician, Dr. Harutiun Shirinian, and Turkish and Armenian pharmacists revealed that the bread in question had been made from a mixture of wheat and rye flour, which caused the blue streaks in it, but that it was perfectly safe to eat. They further noted that the symptoms that had cropped up the night before had disappeared and that no one had been poisoned.30 The local press, which was soon echoed by the press in Istanbul, nevertheless reported the official version of events, according to which Armenian bakers had poisoned the soldiers. This version was never retracted, despite Bishop Knel Kalemkiarian’s repeated appeals to the vali.31 A witness also reported that a mutilated body found near the suburb of Hoğtar had been exhibited in front of the town hall for 24 hours “in order to incite the Turks against the Armenians.”32

The Armenians’ situation was not improved by the event that occurred shortly thereafter – an 18 January 1915 reception held in Sıvas for Vice-Generalissimo Enver, who was on his way back from the front after the Ottoman defeat at Sarıkamiş. The famous Murad Khrimian (Sepastatsi Murad), a former Dashnak fedayi who had been rehabilitated after the proclamation of the Constitution,33 went out to greet Enver and had a conversation with him. The minister emphasized that two members of the Dashnak leadership in Sıvas, Vahan Vartanian and Ohannes Poladian, had shown great courage during the fighting, but also stressed that the troops had been poorly trained.34 When Enver received a visit by the Armenian religious and political leaders, he reminded them that he had been saved a few days earlier by Lieutenant Hovhannes Aginian, who had died of his wounds shortly thereafter, adding that the Armenian recruits had fought bravely.35 These remarks, however, remained confined to the context of this courtesy visit. As was the case in other provinces, the Dashnaks remained the local authorities’ privileged interlocutors in the first few months of the war. Murad Khrimian often met with Muammer to clear up “misunderstandings” with him – that is, to defuse provocations. Thus, in fall 1914, he was able to negotiate the staggered mobilization of different age cohorts with the authorities, the vali’s hostility to the idea notwithstanding.36 Yet mistrust continued to be perceptible on both sides. Like the valis of Dyarbekir and Trebizond, Ahmed Muammer too was the local leader of the Teşkilât-ı Mahsusa. It was on his orders that, in November 1914, the president of the vilayet court released 124 criminals from the prison of Bünyan to incorporate them into a unit then being formed.37 An Armenian source observed that the squadron of çetes created in late fall 1914 had initially conducted operations “amid the greatest possible secrecy, and, later, in the open.”38 But Sıvas was also a city through which irregular troops sent from the western parts of the empire passed in transit. For example, on 10 December 1914, a unit of 1,200 çetes en route for Erzerum arrived in Sıvas and was given a hero’s welcome by the Turkish populace. In contrast, the Armenian villagers’ memory of these men’s passage through the area was a much less happy one, for they wreaked havoc on the villages of the plain.39 Bekir Sâmi Bey’s group, comprising 800 irregulars, 20 of them officers, spent the month of January in Govdun, the village near Hafiz in which Murad Khrimian lived. The çetes were, however, careful not to mistreat the population, with which they were billeted, and even showed the celebrated former fedayi respectful deference.40 The handful of abuses noted in this period may, moreover, be put down to these men’s criminal past. The vilayet of Sıvas did not really begin to feel the effects of the war until after the failure of the Sarıkamiş offensive. Thus, from 2 February on, the Armenian villages on the plain of Sıvas were surrounded by what was left of the Third Army, which took up quarters there and lived off the residents. Typhus raged among these soldiers and soon spread to the villagers as well. The villages of Kızılbaş also had to help feed and lodge these men. Turkish localities, however, were spared.41 Govdun seems to have been required to make a particularly heavy contribution to the war effort, perhaps because Murad lived there. Although one-and-a-half battalions of the regular army had already been billeted in the village, a new squadron of çetes arrived from Istanbul to take up quarters there on 30 January. Now, however, the tone changed: the Çerkez officer in command of the unit immediately attacked Murad for having struggled “against Islam for twenty years,” and threatened the villagers. The fedayi answered that the sole purpose of his fight had been to establish the “constitution,” adding that “the village was not in revolt” and appealing for corroboration to the officer responsible for the regular troops stationed in the village. The next day, when Murad visited the commander of the brigade posted in the sector in order to request that he send these çetes away, he was told that this squadron answered directly to the vali, not to the military authorities.42 Murad therefore left for Sıvas in order to meet with Muammer. He described the unbearable situation of the rural populations of the vilayet, who were expected to feed and quarter thousands of soldiers. By way of his answer, the vali remarked: “It seems that the Armenian population is unhappy over our successes.” In other words, the Ottoman “successes” – the defeat at Sarıkamiş had not yet been publicly announced – supposedly irritated the Armenians, who were suspected of harboring sympathies for the Russians. Murad understood the message very clearly and immediately convoked a meeting of the Armenian representatives of all confessions in order to evaluate the authorities’ intentions, which were deemed alarming. The Armenian leaders decided to remain vigilant in order to defuse provocations,43 the more so in that they had already observed that the authorities had not reacted when, during the January 1915 debacle, Armenian soldiers responsible for transport had been massacred near the Erzincan-Sıvas road.44 The Armenians’ alarm was heightened when they learned on 8 February that the village of Piurk, located in the kaza of Suşehir, had been destroyed under suspect circumstances by a recently formed group of çetes that included Zaralı Mahir, one of the men who had murdered Sahag Odabashian.45 This massacre, during which several men had been killed, was all the more symbolic in that Piurk had had a reputation as an Armenian fedayi center in Abdülhamid’s day.46 The Armenians were also worried because of alarmist remarks that German officers stationed in Sıvas were supposed to have made, according to Dr. Hayranian, an army doctor educated in Germany who was a friend of Dr. Paul Rohrbach’s.47 A German doctor, whom Hayranian had asked to intercede with the authorities after the attack on Piurk, had answered: “What can I do? What can I say? Think rather about how to die with honor.”48

In the first half of February, the arrival of between 1,500 and 1,700 Russian prisoners-of-war on the plain of Sıvas offered the local authorities another opportunity to paint the Armenians as suspect. Certain villages had been asked to lodge and feed these Russians. Eight men who had arrived in terrible condition, suffering from typhus, died the first night, despite the care the villagers gave them. The soldiers escorting them were nevertheless opposed to the idea of burying them. Having ignored this prohibition to bury them, the Armenian villagers were immediately accused of rebelling and treated accordingly.49 The authorities pretended not to know that the Christian funeral rite required that the dead be buried regardless of identity. It is, however, also possible to chalk these events up to the bitterness engendered by the defeat at Sarıkamiş.

In March, the Young Turk members of parliament from Çanğırı, Harput, and Erzerum were invited to come to Sıvas by the CUP’s responsible secretary, Erzrumlı Gani, in order to speak before the Young Turk club and in the mosques.50 According to a number of concurring sources, Fazıl Berki, the representative from Çanğırı, declared: “Our true enemies are close to us, among us – they are the Armenians … who are sapping the foundations of our state. That is why we must first wipe out these domestic foes.”51 These remarks, based on a speech that Bahaeddin Şakir had made in the same period,52 circulated so openly in Sıvas that Bishop Kalemkiarian felt the need to go to see the vali and ask what they meant.53 The role of Erzrumlı Gani Bey appears here for the first time. This Young Turk leader, a native of Erzerum who had received his officer’s training at Istanbul’s Military Academy (Harbiye), arrived in Sıvas in fall 1914.54 There, he organized a lecture that Dr. Şakir had delivered before the Ittihadist club, probably on his way back to Istanbul in early March 1915.55 Gani worked with the vali, Muammer, and his henchmen – the parliamentary representative from Çanğırı, Dr. Fazıl Berki; the representative from Sıvas, Rasim Bey; and Colonel Ali Effendi, the deputy commander of the Tenth Army Corps – on the plan to extirpate the Armenians.56

Muammer, however, entrusted the organization of new squadrons of çetes in the vilayet to the parliamentary representative Rasim Bey in March 1915.57 Approximately 4,000 çetes were recruited and given gendarmes’ uniforms. This group was drawn, notably, from the Kurdish population of Darende, Karapapak who had come from the Caucasus, and freed felons. Two thousand of these “gendarmes” were to go to Sıvas, while the others were to be dispatched to the neighboring villages.58 In the same period, there was a sharp rise in desertions among the Armenian recruits, who had suffered increasing harassment and persecution. The medreses of Şifahdiye and Gök were converted into detention centers for Armenian soldiers.59 Thus, by March, the first signs of the events to come could be discerned. The most symbolic act was the arrest, around 15 March, of 17 political leaders and teachers in Merzifun and Amasia – among them Kakig Ozanian, Mamigon Varzhabedian, and Khachig Atamian – who were immediately transferred to Sıvas and interned in the medrese of Şifahdiye.60 The Armenian sources say nothing about the motives that the authorities invoked to justify these arrests, but note that they preceded the arrests of the political and intellectual elites of Sıvas by two weeks. In the provincial capital, the alleged flight of a Russian officer served as a pretext for the arrests of a hotelier, Manug Beylerian; Cholak Hampartzumian; and, on 28 March, of the pharmacist and Dashnak leader Vahan Vartanian, along with his colleagues Hovhannes Poladian and Harutiun Vartigian; the Hnchaks’ Krikor Karamanugian, Murad Gurigian, and Dikran Apelian; and the dragoman of the vilayet, Mardiros Kaprielian, all of whom were summoned before Muammer and then immediately placed under arrest. On 7 May, after spending 40 days in the central prison, these men were put in chains and sent to Yeni Han on the Sıvas-Tokat-Samsun road. Muammer, the CUP’s responsible secretary Gani Bey, and Colonel Pertev, the commander of the Tenth Army Corps, joined them in a place called Maşadlar Yeri, where they interrogated the Armenian leaders about their plans for an insurrection and the quantity of arms in their possession, and then put them to death.61 Bishop Kalemkiarian’s protests to the vali proved to be in vain, as did the request from Dr. Haranian to liberate the detainees; indeed, Haranian’s bold intervention cost him his life.62 It was Murad Khrimian, however, who was Muammer’s greatest cause of concern. On Monday, 29 March – that is, the day after the Sıvas leaders were arrested – the vali sent Keleş Bey, the commander of the gendarmerie, to Sıvas, accompanied by a squadron. Keleş Bey told Murad to go with him to Sıvas because Muammer “wished” to see him. After giving orders to set a resplendent table for his guests, the fedayi disappeared without a trace.63 The forces of the gendarmerie sent to look for him arrested the male population of the village of Khandzar, which was suspected of having given Murad shelter, and proceeded to kill the men in the Seyfe Gorge, a spot two hours to the east of the village.64 This massacre, which occurred in early April, marked the end of the first phase of operations, the main target of which had been the political elites of Sıvas and conscripts from the city.

Deportations and Massacres in the Sancak of Sıvas

In 1914, the Armenian population of the sancak of Sıvas alone was 116,817. The Armenians lived in 46 towns and villages.65 The kaza of Sıvas had 37 towns and villages, with a total Armenian population of 31,185, almost 20,000 of whom lived in the regional capital.66 Demographic considerations perhaps explain why the first operations, the official purpose of which was to track down deserters and collect weapons, targeted only the Halys/Kızılımak valley, focusing on the villages in the northern part of it. Moreover, early in April 1915 the authorities took all the measures required to completely cut off relations and correspondence between Sıvas and the neighboring villages: “no one knew what was going on, even in a village just an hour away.”67

We have information about one of the battalions of çetes created on Muammer’s initiative, the one commanded by Kütükoğlu Hüseyin and Haralı Mahir, the murderers of Father Sahag Odabashian.68 This battalion conducted its operations in the localities of the Kızılırmak valley from 2 April onward.69 It had been given the mission of arresting the adolescents, village priests, schoolteachers, and notables who had not been conscripted. According to Armenian sources, these operations were accompanied by looting, rapes, and murders, and were followed by the transfer of the men who had been arrested to Zara/Koçhisar or Sıvas. Some of these men were killed in the Seyfe gorge or at the level of the Boğaz bridge. The others were interned in the city, in the medreses of Şifahdiye and Gök.70 We also know that a battalion of gendarmes commanded by Ali Şerif Bey carried out operations in this valley. The killing of the men of the villages of Khorasan and Aghdk, located on the outskirts of Koçhisar, were its work; the villagers were put to death in the Bunağ Gorge.71 It is probable that the 4,000 çetes stationed throughout the sancak were given similar missions in other districts during these operations, which took place in April and May. A squadron even took up a position near Sıvas, on the banks of the Kızılırmak in a place called Paşa Çayiri, which was converted into a slaughterhouse for prisoners who had been interned in the regional capital.72

The Armenians of the city of Sıvas were not really targeted until May 1915. One of the first measures taken concerned the Armenian employees of the Post and Telegraph Office. The minister responsible for it issued an order by telegraph calling for their immediate dismissal,73 which was followed by that of all other Armenian civil servants, such as municipal physicians and pharmacists, gendarmes, and so on.74 The monastery of St. Nshan came under full army control. Finally, the authorities ordered that the population turn in its weapons on pain of court-martial. At the vali’s request, Bishop Kalemkiarian asked his flock in a Sunday sermon to obey the government’s orders. Armenians and Turks handed over their weapons (for the sake of appearances, the decree applied to the entire population). Of course, Muammer invoked the Armenians’ lack of cooperation to justify launching a vast confiscation campaign that led in turn to the arrests of the city’s notables (one of the first to be imprisoned was the famous arms-maker of Sıvas, Mgrdich Norhadian).75 The government’s propaganda now took on a more vehement tone. The authorities began by putting the weapons turned in by the Armenians on display, adding to these the battle arms in the barracks and photographing the pile. The vali also sent a report to the Sublime Porte in which he accused the Armenians of treason.76

There also exist reports of a meeting held in Sıvas sometime in May that was attended by Turkish notables and Çerkez and Kurdish chiefs (from the kaza of Koçkiri), to whom the vali issued directives about the treatment to be meted out to the Armenian population. After the Armenians had been demonized for several weeks, the situation seemed ripe for the transition to the practical phase of the extermination. A Turkish liberal, Ellezzâde Halil Bey, told one of his Armenian friends, “You cannot imagine what they are preparing to do to you.”77 Among the Armenians, a rumor was making the rounds about how “black lists” containing the names of the first men to be arrested were being drawn up for every quarter of the city. It would appear that a general list was produced by combining material from three sources: the heads of the various neighborhoods; artisans’ associations, which the CUP club had asked to produce names; and the police. Hnchak Party and Dashnak Party clubs were searched and their archives impounded.78 Down to the end of May, however, the arrests carried out across the vilayet had involved only 400 to 500 men.79 Finally, there are indications that Muammer made a tour of the kazas of his vilayet, notably Merzifun80 and Tokat,81 in late May and early June.

Here, too, the first victims of this operational phase were those people most deeply involved in local political and social life, as well as those with connections to foreign institutions, such as the physicians at the American hospital or the teachers at Merzifun’s Anatolia College. Thus, the authorities sought to isolate these establishments. They gradually requisitioned their buildings and then forced the missionaries to leave the region.82 On 15 June, 12 people were publicly hanged. These men were political activists, four deserters from Divrig/Divriği, and people who had been accused, apparently unjustly, of a murder that had occurred several years earlier.83 This spectacle took place shortly before the beginning of the systematic operations conducted by the police and the gendarmerie that began on Wednesday, 16 June 1915. On that day, 3,000 to 3,500 men were arrested in their places of work or their homes and interned in the central prison or the cellars of the medreses of Şifahdiye and Gök.84 Among them were teachers from the Aramian and Sanasarian lycées, including Mihran Isbirian, Mihran Chukasezian, Hagop Mnjugian, and Hayg Srabian; Mikayel Frengulian, a teacher from the American middle school; Avedis Semerjian, Krikor Gdigian, and Senig Baliozian from the Jesuit middle school; the members of the Diocesan Council, including its leading members Voskan Aslan and Benyamin Topalian; and staff members of charitable organizations, political activists, doctors, pharmacists, and all those who counted in Sıvas, such as the police officers Ara Baliozian and Mgrdich Bujakjian, the surveyor Serope Odabashian, the lawyer Mgrdich Poladian, the Telegraph Office employee Aram Aginian, the municipal architect Hovhannes Frengulian, the photographer H. Enkababian, and the former dragoman of the French consulate, Manug Ansurian.85 Ernest Partridge notes that no proof whatsoever of the guilt of these men was put forward, that they were never indicted, and that no one knew why the authorities had arrested them. The vali repeatedly assured the American minister that they would be “freed and sent on their way with their families.”86 The Armenian bishop was given a more original explanation: Muammer told him that he had had the men interned to protect them from the possibility of a massacre, since “prison was the safest place” for them. He also advised the prelate not to get involved in these matters, especially because he was not yet acquainted with the Armenians of Sıvas. Only he, the vali, knew “just how dangerous this element was.”87

The first round-up was followed by a second wave of arrests, launched on 23 June, that led to the apprehension of around 1,000 men. Thus, a total of some 5,000 people were crammed into the city’s central prison and the cellars of the medreses.88 Similar operations were conducted in the second half of June in Tokat, Amasia, Merzifun, Zile, Niksar, Hereke, and so on, with the apprehended men rapidly killed in the environs of these localities.89 In Sıvas, Muammer seems to have opted for another method: as we shall see, it was only after carrying out the deportations that he concerned himself, early in August, with the fate of these prisoners. Despite its proven utility, Sıvas’ Armenian national hospital, which had put 150 beds at the army’s disposal and played an important role in fighting the typhus epidemic, was confiscated by the authorities. Most of its staff were arrested90 and put to death shortly thereafter.

The pretrial investigation of Gani Bey, the CUP’s responsible secretary in Sıvas, mentions a trip that he made to Istanbul in the second half of June 1915 in order to take part in a coordinating meeting with his colleagues from other vilayets.91 We do not have further details about the directives that were issued to the Ittihadist delegates there, but it seems reasonable to suppose that they bore on the deportations that began in very many different locales in early July.

The first to be deported were the inhabitants of the villages located in the upper part of the Halys/Kızılırmak valley in the kazas of Koçhisar and Koçkiri. These deportees were put on the road in the latter half of June, before the official publication of the expulsion decree. As elsewhere, first the adolescent and adult men were arrested and killed, after which women and children were set marching southward. By 29 June, the deportation of the villagers from the Kızılırmak valley had already been completed.92

The official deportation order was not promulgated until late June – 30 June, to be exact.93 On 1 July, Ahmed Muammer convoked the Armenian orthodox primate, Bishop Kalemkiarian, as well as his Catholic counterpart, Bishop Levon Kechejian, to inform them that the first convoy would have to leave the city on Monday, 5 July, bound for Mesopotamia. On Kalemkiarian’s account, the vali justified this measure by recalling that the Armenians had been living “for six hundred years under the glorious protection of the Ottoman state” and had profited from its sultans’ tolerance, which had enabled them to preserve their language and religion and to prosper to the point that “trade and the crafts were entirely in [their] hands.” Finally, Muammer pointed out that if he had not been vigilant and anticipated developments, an “insurrection would also have broken out and you would have – God forbid – stabbed the Ottoman army in the back.”94 This condensed historical overview no doubt reflected the sentiment prevailing among the Young Turks at the time, as well as the leitmotif of official propaganda.

Armenian sources depict the desperate attempts of some Armenian women to intervene with the vali and Sıvas’s Turkish dignitaries, who advised them to convert while waiting for “the storm to blow over.” It would appear that a few dozen craftsmen at most were authorized to remain in the city after agreeing to become Muslims. In any event, this possibility of escaping deportation was briefly but vigorously95 debated by the detainees, who brought the debate to a swift close since they seemed to have understood that this semi-official opening was a lure. On Sunday, 4 July, a final church service was held in the cathedral. When it was over, the bishop took the keys of the building to the vali, who refused to accept them.96 According to G. Kapigian, who observed these events with a certain perspicacity, Muammer had deftly profited from the general despair in order to spread rumors to the effect that the anti-Armenian measures were just temporary, even justifying the deportees’ hopes of a swift return. Indications are that the vali had worried until the last moment that the Armenians might rise up in revolt despite the fact that the community’s most vigorous elements had been jailed. As in Harput/Mezreh, the Armenians tried to put their most valuable belongings in the safekeeping of the American missionaries, especially Dr. Clark and Mary Graffam, but the police limited their ability to do so by blocking the entrance to the American mission. Funds deposited with the Banque Ottomane were also frozen and then confiscated on Muammer’s orders. The vali recommended that the Armenians register their property and deposit it in the cathedral, which had been transformed into a warehouse to that end. Many Armenians, however, chose to bury their savings. It must be added that the authorities had prohibited the sale of moveable property in advance and this ordinance was, by and large, respected.97 In other words, the Armenians’ assets were turned over in their entirety to the commission charged with “administering” them. It must finally be noted that, shortly before the departure of the first convoy, three regiments commanded by Neşed Pasha set out for Şabinkarahisar in order to put down the Armenian resistance that had been organized there.

The Deportation of 5,850 Families from Sıvas

Between Monday, 5 July and Sunday, 18 July, Sıvas’s 5,850 Armenian families were deported in a total of 14 convoys, at a rate of one convoy daily, with an average of 400 households in each caravan.98 The operation was carried out neighborhood by neighborhood – even street by street – in an order that suggests the most affluent families were deported first and the most modest quarters dealt with last. However, some 70 artisan households were allowed to remain behind, along with nine students from the Sanasarian lycée, the vali’s son’s violin teacher K. Koyunian, four physicians (Harutiun Shirinian, Karekin Suni, N. Bayenderian, and Gozmas Mesiayan), the 80 orphans in the Swiss orphanage, three officers (Dikran Kuyumjian, Vartan Parunagian, and Vartan Telalian), the pharmacists Hovhannes Mesiayan and Ardashes Aivazian, and above all the approximately 4,000 recruits from the region assigned to labor battalions.99 The inhabitants of a village near the city, Tavra – millers who provided the city and the army with its flour – were also temporarily allowed to stay behind, as were the peasants from Prkenik, Ulash, and Ttmaj, who produced the bulk of the vilayet’s wheat.100

On the morning of 5 July, Muammer oversaw the departure of the first convoy from the balcony of his residence. A dense crowd watched the spectacle, apparently with satisfaction, exclaiming, “The thermalistes [hydrotherapists] are leaving.” A bridge known as Twisted Bridge served as a checkpoint: the government officials stationed there recorded the names of men, women, boys, and girls on separate lists.101

The first measure taken by the vali was to post a squadron of the Special Organization in the Yırıhi Han Gorge on the other bank of the Kızılırmak river. This group, dubbed Emniyet Komisioni, was commanded by Emirpaşoğlu Hamid, the chief of the Çerkez of Uzunyayla; Halil Bey, the commanding officer of the squadrons of çetes and Muammer’s yaver (assistant); Bacanakoğlu Edhem; Kütükoğlu Hüseyin, who spoke Armenian and was the most knowledgeable about Sıvas’ Armenians; and Tütünci Haci Halil. These çetes’ mission was to single out the men still present in the convoys, especially if they were young, and to suggest that the deportees leave their money and valuables behind. They first looted the groups of deportees even before they were put on the road.102 All the convoys from the sancak of Sıvas followed, grosso modo, the same trajectory and were subjected to the same fate. The deportations were carried out along a route that ran through Sıvas, Tecirhan, Mağara, Kangal, Alacahan, Kötihan, Hasançelebi, Hekimhan, Hasanbadrig, Aruzi Yazi, the Kirk Göz Bridge, Fırıncilar, Zeydağ, and Gergerdağ (the mountains of Kanlı Dere where the Kurdish chieftains of the Reşvan tribe, Zeynel Bey and Haci Bedri Ağa, officiated), then headed toward Adiyaman and Samsat, crossed the Euphrates near Gözen, and took the road running through Suruc, Urfa, Viranşehir, and Ras ul-Ayn, or the road to Mosul, or, again, the road that led to Aleppo via Bab and Mumbuc. The few known survivors were those who reached Hama, Homs, or, in the case of the most unfortunate, Rakka or Der Zor.103 We shall here content ourselves with describing in detail the fate of the eleventh caravan, which left Sıvas on 15 July, which comprised 400 families from Karod Sokak, Dzadzug Aghpiur, Holy Savior, Ğanli Bağçe, Hasanlı, Taykesens, and Han Paşi. Among them was the family of Garabed Kapigian, a privileged witness to the events that transpired in Sıvas. Kapigian, a former Hnchak party activist who had lived for a long time in Istanbul, was one of the rare adult men over 40 still “free.” The escort of gendarmes was commanded by Ali Çavuş, a Turk well known by a certain number of the deportees.104 After being looted for the first time in the outskirts of Sıvas, the eleventh convoy continued its journey via Maragha and Kangal, whose Armenians had already been deported. Kapigian notes, however, that a banker from Sıvas, Ghazar Tanderjian, who had left with the first convoy, managed to remain in Kangal by converting with his whole family to Islam. In the field near the village that served as a campground, the deportees from Sıvas discovered two caravans who had arrived the day before from Samsun, Merzifun, Amasia, and Tokat. The scant information that they gleaned from the deportees of these convoys confirms that the same scenario had unfolded in those towns as well. It should be noted, however, that all males over the age of eight in these convoys were separated from the others and killed in Şarkışla by Turkish and Çerkez villagers on the orders of Halil Bey. Before the convoy left, Kapigian saw a brigade of Armenian worker-soldiers arrive. They had been charged with demolishing the church in Kangal.105

On 24 July, the eleventh convoy from Sıvas arrived in the Yırıhi Han Gorge, located outside the village of Alacahan. Like the groups that had preceded it, the caravan had to pass through this filter, where the çetes commanded by Emirpaşaoğlu Hamid Bey were waiting for it. Hamid immediately ordered the men to step out of the convoy and line up in front of the khan because he wished to address them. His remarks, reported by Kapigian, are worth briefly pausing over. Very courteously, the çete leader apologized for his failure to safeguard the roads against “the permanent attacks of the Kurdish savages.” It was because of these attacks, he went on, that the government, “always solicitous of your welfare,” had dispatched the Emniyet Komisioni to the Yırıhi Han Gorge and charged it with taking in hand and registering in the deportees’ names all the gold, money, jewels, and other valuables they had with them (“everything you have in your possession”). Hamid Bey promised that these items would be restored to their owners as soon as the convoy reached Malatia. In a less friendly tone, he warned everyone that systematic body searches would be conducted and that anyone discovered to have held back the least little coin would be shot on the spot. Even before the group was dispersed, Kapigian reports, a mounted “gendarme” galloped onto the scene and announced that the convoy from Samsun, which had set out that very morning, had been attacked by Kurds, who had looted the deportees and massacred a number of people. Kapigian says that this carefully staged show, which was supposed to illustrate the dangers to which the deportees were exposed around Yırıhi Han, hardly convinced the deportees. Rather, it plunged them into a dilemma:106 how, in such an environment, should they hide their possessions, the means of guaranteeing their survival? Obviously, this question confronted all the deportees – or at any rate, all who possessed means. In this curious game that consisted in relieving the deportees of all their possessions in order gradually to deprive them of the means of survival, the victims and their executioners were in a one-way face-off. Kapigian lists the stratagems to which the Armenians resorted: some swallowed gold coins, others hid jewels on their children, and still others hastily buried their purses. The government’s solicitude evaporated at this point. The çetes proceeded to carry out systematic body searches on the deportees. Already experienced, they no doubt knew better than the victims the various ways of hiding money and jewels. Threats, blackmail, and violence were enough to change the minds of those deportees who had been trying to hold back at least some of their possessions in order to be able to proceed on their way.

Thus, the Emniyet Komisioni served as a framework for the official pillage of the deportees before they were turned over to the looters. In other words, the system that Muammer had put in place in Yırıhi Han was designed to secure the lion’s share of the booty for the Ittihadist party-state before the deportees were turned over to the çetes or peasants mobilized along the routes that the convoys went down. However, the CUP’s official bodies had to overcome the recurrent problem of the indelicacy or cupidity of the “civil servants” in charge of these official stations set up for the seizure of Armenian property. This explains the extraordinary formality that characterized the operations by which the deportees were stripped of their property and the fact that someone close to the vali was generally on hand with the obvious mission of supervising the operations. Kapigian notes the great care taken by the commission to register the deportees’ property, counting and recounting their cash and describing their jewels in great detail.

This formality, however, gave way to more muscular methods when the family heads were summoned, one by one – a few of them were men, but most were women – to appear before the members of the commission presided over by Hamid Bey in order to relinquish their possessions. Systematically, they were told that what they had turned over was far from being everything they owned, a remonstrance that was usually accompanied by a bastinado with which the commission obtained an additional effort from the deportees. The commission worked all the more effectively because its members knew their victims rather well; they were aware of the position they occupied in society and consequently had a rather precise notion of the means at their disposal. After this ritual, which lasted for several hours, the çetes conducted searches of the other members of the convoy, down to the most private parts of their bodies. In the final stage of the operation, the notables who had escaped the round-ups in the city were removed from the convoy and summarily killed.107 Kapigian’s brief description of the fates reserved for the preceding and following convoys shows that the same procedure was followed every time.

When the convoy reached Kötü Han on the boundary between the vilayets of Sıvas and Mamuret ul-Aziz, its escort was relieved. Kurdish gendarmes now took the place of the Turkish gendarmes. According to Kapigian, bakshish in the usual amount was not enough to satisfy this new escort and convince it to step in when local villagers tried to profit from the passage of a convoy by acquiring a few valuables or abducting a girl. The intervention of a mullah made it possible, however, to curb these appetites, so that the profits were made by the sale of fresh produce – at obviously exorbitant prices.108

It was, however, only after they reached Hasançelebi, in the northern part of the sancak of Malatia, that the convoys began to be systematically decimated. In theory, it was a 30-hour journey from Sıvas to Hasançelebi, but the eleventh convoy from Sıvas needed no fewer than 15 days to make the trip, indicating that the individual stages of the journey were not long and were probably even bearable for old people. Moreover, during this first stage of the trek, human losses were limited to the dignitaries killed at Yırıhi Han. It was as if it had been decided to bring the deportees out of their native sancak before moving on to the exterminatory phase in the proper sense of the word; it was as if the local authorities wished to pin the blame for the programmed crimes on the civil servants of the neighboring region or the Kurdish population, which systematically took the role of the “black sheep.”

Hasançelebi was a site that had been chosen for the systematic extermination of all the males in the convoys from Samsun and the kazas of the Sıvas vilayet. The advantage of the valley that ran from the village outward was that it lay squeezed between high mountains: deportees from the convoys that had arrived from Samsun, Tokat, Amasia, Sıvas and their rural zones in the preceding days were concentrated in the immense camp located in it. Amid indescribable chaos, the groups camped in two distinct areas. Kurdish çetes crammed in young boys, adolescents, adults, and old men from this multitude; they were escorted from the camp in small groups and briefly interned in a stable pressed into service as a prison. According to Kapigian, those in charge of the camp granted the new arrivals a day’s respite – that is, enough time to unload their carts and pitch tents. Around 300 men in the eleventh convoy from Sıvas were led off in this fashion.109 Here, too, the procedure followed was almost mechanical. Every night, the people arrested in the morning were removed from the stable, tied together in pairs, and escorted to a spot behind a promontory in a gorge. There the executioners killed their prisoners with knives or axes and threw them from the promontory. The next morning new arrests were made, and so on. On Kapigian’s estimate, more than 4,000 males in the 14 convoys from Sıvas were killed in Hasançelebi. Boys under ten, however, were spared.110

Reverend Bauernfeind, who left his mission in Malatia on 11 August, went to Kırk Göz at dawn the same day,111 and better understood

why our coach-drivers wanted to reach Hasanbadrig before the heat of noon at all costs. The stench of the corpses – which is all too familiar to us – from about a hundred, or perhaps more, individual and mass graves to the left and right, were so poorly dug that, here and there, parts of the bodies stuck up out of them. Further on, the graves disappear, but not the dead: men, women, and children lie stretched out beside the road, in the dust, either in rags or stark naked, in terrible condition, more or less decomposed. In the space of a four hours’ journey to Hasanbadrig (roughly twenty kilometers), we counted one hundred bodies. It goes without saying that in this region full of valleys, many of the corpses escaped our gaze.

Further north, shortly before Hekimhan, Bauernfeind again saw corpses, “as a rule, in pairs – again, males – in a state that inevitably led one to suspect that they had met a violent death. Because the terrain was so rugged, we were not able to see many others, but we could smell them.” However, subsequent observations made by the German minister, who went the other way, down the route the convoys had taken, confirm that no significant violence had been inflicted on the deportees beyond Hasançelebi.112

Hekimhan, the next stage, seems above all to have served to eliminate the handful of men who escaped being killed at Hasançelebi.113 For its part, the transit camp, located further to the south, near the Kırk Göz Bridge over the Tohma Çay, where the secretary of the Malatia gendarmerie Tayar Bey presided over operations with a squad of çetes “disguised as gendarmes,”114 served to regulate the flow of convoys that converged on it from the regions of the Black Sea coast, Erzerum, and the northern part of Harput. This no doubt explains why the authorities appointed a Sevkiyat Memuri (“director of the deportation”) there.115 From that point on, the convoys from Samsun and the different kazas of Sıvas took the route followed by everyone, else and shared their fate.

The deportees from Sıvas, like their compatriots from other regions, were also concentrated in the immense camp at Fırıncilar, one of the main killing fields chosen by the Teşkilât-ı Mahsusa. It was supervised by Haci Baloşzâde Mehmed Nuri Bey, a parliamentary representative from Dersim, and his brother Ali Paşa.116 As was the case with other groups, the authorities removed the boys under ten and the girls under 15 from the convoys in order to send them on to Malatia, where they were ultimately killed.117 Kapigian, who had survived up to this point by disguising himself as a woman, confirms the miserable plight of the refugees, who had been weakened by the journey, deprived of means of transport, and stripped of virtually all their belongings as a result of the successive acts of pillage to which they had been subjected.118 It was in Fırıncilar that the deportees from Sıvas had been deprived of their means of transport, which were officially confiscated by the requisitions commission to meet the needs of the army.119

Here Kapigian observed the arrival of caravans of deportees from the Black Sea coast – particularly Kirason, Ordu, and Çarşamba – as well as the villages of Şabinkarahisar. They were in a more than wretched state because the women and children – there was not a single man in these groups – had made the entire journey on foot. Fırıncilar also served as a graveyard for the oldest deportees, who were unable to go on, and the small children abandoned by their mothers because they could no longer carry them.120

Kapigian’s convoy left Fırıncilar on 18 August, just before the third caravan from Erzerum arrived there. All the groups took a mountain trail known as Nal Töken (“which makes the horseshoes fall off”), then entered the appropriately named Kanlı Dere (“blood valley”) Gorge, where Zeynel Bey and Haci Bedri Ağa, two Kurdish chieftains of the Reşvan tribe, were waiting for them with their squadrons of çetes.121 One by one, the deportees were stripped of their clothing and divested of their last possessions. The handful of men still among them was killed, and the most attractive girls and young women were carried off.122 The sites of Fırıncilar-Kanlı Dere went out of operation in September once the flood of convoys had tapered off. According to Mrs. Aristakesian, who worked as a cook for the commander in charge of the Fırıncilar “camp,” the last deportees who left, basically the sick and elderly, were put to death in a nearby valley.123

Thus, the deportees who arrived at the next way-station, Samsat, were physically diminished and psychologically weakened, if not traumatized. From Samsat, they took the road to Urfa through Karakayık Gorge. On the way, these groups were attacked at precise points and gradually decimated, with the killing taking place notably on the banks of the Euphrates south of Samsat, near the village of Oşin. A few remnants of these convoys nevertheless managed to reach Suruc, Urfa, and then Ras ul-Ayn or Der Zor.124 In the fifth part of the present study, we shall see the fate reserved for these survivors in the second phase of the genocide.

The Kaza of Koçhisar

This kaza, which borders on Sıvas, was located in the upper Halys/Kızılırmak valley. In 1914, it boasted 30 Armenian localities with 13,055 inhabitants and 28 schools with a total enrollment of 2,483. The principal town in the kaza, Koçhisar, had barely 3,000 inhabitants, 2,037 of whom were Armenian.125

The main organizers of the deportations and massacres here were Vefa Bey, the interim kaymakam; Kukuşoğlu Şükru, the mayor and a member of the Ittihad; Salaheddin, a sergeant in the gendarmerie in Koçhisar; Mustaf, an employee in the Tobacco Régie; Adalı Hasan, who organized the deportations in the kaza itself; the Turkish notables Hamdi Effendi, Rıza Effendi, and Sehid Osman Nuri; and the chief of the çetes, Mehmed Çavuş.126

As we have already noted,127 the first arrests here came at the very beginning of April, in both the city and the villages. They were carried out under the leadership of the çete leaders Kütükoğlu Hüseyin and Zarah Mahir. Some of those arrested were put to death in Seyfe Gorge or near the Boğaz Bridge; others were interned in the city in the medreses of Şifahdiye and Gök. But the systematic arrest of the males did not begin until June, particularly in the villages, when 2,000 men, including all the village priests in the kaza, were confined in Koçihisar’s prison and slain before the deportations, in line with the usual procedure. Every night, these men were taken from the city in groups of 100 and killed in Seyfe Gorge or near the Boğaz Bridge.128

The first convoy, made up of villagers, left around 20 June. It was followed by a caravan made up of inhabitants of Koçhisar, 500 of them males. After suffering a first attack by Çerkez from Kuştepe, this convoy reached the village of Ulash, the population of which had, for the time being, been allowed to remain so that it could bring in the wheat harvest. Here the convoy was combined with another comprising 1,000 women and 200 men from the rest of the kaza. Two days later, the group arrived in Hasançelebi, where 200 adolescents were removed from the convoy and killed. The next day, at Hekimhan, the old men were removed from the convoy and massacred. After crossing the Kırk Göz Bridge on the fifth day, the deportees reached Fırıncilar in 36 hours. They remained there for seven days, during which a number of girls and boys were abducted.129 This convoy was in fact one of the first to test the system put in place by the authorities crossing the mountains of Nal Töken. According to a survivor, Zeynel Bey – not Haci Bedri Ağa – ordered that the 200 men still alive be killed, the deportees be pillaged, and the women be stripped in Kanlı Dere Gorge, where thousands of corpses were already strewn over the ground.130 After passing through Adiyaman, the convoy reached the Göksu, near Akçadağ. A number of women were thrown into the river there by Kurds; others were abducted. As they went on toward Suruc, the survivors were combined with what was left of other convoys, thus forming a caravan of 1,500 people. About half of them remained in Suruc, while others continued their trek toward Birecik, Bab, and finally Hama, their “place of residence,” which a few dozen women from Koçhisar managed to reach in fall 1915.131

The Kaza of Koçgiri/Zara

In this rather mountainous kaza in the upper valley of the Halys there were, in 1914, a mere dozen Armenian localities with a total population of 7,651. The principal town in the kaza, Zara, had 6,000 inhabitants, 3,000 of them Armenian. Traversed by the road leading from Sıvas to Erzerum, Zara was mainly a farming town, but it also served as a way-station, with an immense khan that belonged to the Chil Hovhannesians.132

As we have seen, the Armenians in this region were attacked very early on by çetes, notably by the squadron commanded by Zaralı Mahir, a native of the region who, from 2 April 1915, played a crucial role in putting the men of the kaza to death in Seyfe Gorge or near the Boğaz Bridge.133 We do not know the exact date on which the convoys left Zara, though it was probably between 20 and 29 June. We do know, however, that they took a different route than the deportees from Sıvas, because they headed toward Divrig/Divriği and then Harput, Maden, Severek, Urfa, Viranşehir, and Rakka.134

Apart from Mahir, those mainly responsible for the persecutions were the kaymakam, Hüseyin Hüsni (who served in this post from 13 October 1912 to 5 August 1916), Kör Hakkı, Kebabci Ahmed, and Bakkalci Ahmed.135 Because the army needed their services, a few craftsmen, notably a blacksmith, were allowed to remain in the kaza on the condition that they convert to Islam.136

The Kaza of Yeni Han

The two Armenian localities in the kaza, the administrative seat Yeni Han (pop. 1,461) and Kavak (pop. 630), were located near the road leading from Sivas to Tokat and Samsun.137 Responsible for organizing the deportation of the kaza’s Armenians toward the end of June 1915, after the men had been put to death in Maşadlar Yeri, near Yeni Han, was its kaymakam, Reşid Bey, who held his post from 2 December 1914 to 12 November 1915.

The Kaza of Şarkişla/Tenus

This agricultural kaza, close to Sıvas and traversed by the Halys, boasted 26 Armenian localities in 1914, with a total population of 21,063. The most important of these was Gemerek, which was then home to no fewer than 5,212 Armenians. The kaza had some 20 churches and 21 schools with a total enrolment of 1,988.138

The kaymakam, Cemil Bey, who served from 8 May 1914 to 4 September 1915, first organized the arrest of 400 villagers in the environs of Şarkışla, who were killed there night after night in groups of twenty. The deportation took place early in July. In Kangal, one of the first convoys was combined with a caravan from Sıvas, forming a group of 5,000 Armenians. This convoy then followed the usual route, passing through Alacahan, where the men were removed and liquidated, and Kötü Han, where Emirpaşaoğlu Hamid Bey’s çetes were waiting for them. There, 2,000 men from Sıvas and the environs of Şarkışla were seized, tied up, and brought before Hamid, who knew most of them from Sıvas and thus how much each of them possessed. He managed to extract seven bags of gold from them before dispatching convoys toward Hasançelebi, Hekimhan, Hasanbadrig, Kırk Göz, and Fırıncilar. Almost all were eliminated during these stages of their trek; none reached Samsat.139

Gemerek, which together with the surrounding villages formed a dense group of Armenians, was given separate treatment. Its müdir, Çerkez Yusuf Effendi, called on his Çerkez compatriots from Yayla (in the kaza of Aziziye) for help in slaying the men of Gemerek, Çisanlu, and Karapunar. A few notables from Gemerek were even publicly hanged, after which the women and children were put on the road to Kangal, joining the flood of deportees from Sıvas and regions to the north.140 Besides the müdir of the nahie of Gemerek, the main organizers of the massacre of the males – adolescents over age 13 met the same fate as adults – were Kör Velioğlu Ummet, Kayserlı Cemal Effendi, Talaslı Mükremin, Şarkışlayi Mehmed Effendi, Colonel Talaslı Behcet Bey, and the müdir Ahmed Effendi.141

Approximately 3,000 Armenians from the villages of Shepni, Dendel, Burhan, and Tekmen took refuge in a huge cave in the highlands around Ak Dağ, where they fought off some 2,000 regular soldiers backed up by irregulars for several days. Some 15 men survived the massacre that followed the fighting. The women and children were deported.142

The Kazas of Bünyan and Aziziye

On the eve of the First World War, there were only 5,887 Armenians in Bunyan and Aziziye; 1,106 lived in the latter kaza, almost all of them in the principal town.143 The arrest of the Armenian notables here was orchestrated by the head of the local Ittihad club, Havasoğlu Haci Hüseyin, with the support of the kaymakam, Hamid Nuri Bey (who held his post from 17 October 1914 to 22 October 1915). The pillage of Armenian property was directed by Hayreddin Bey, the head of the emvalı metruke. It mainly benefited, however, a few Turkish eşrefs from the district: Sofoyoğlu Mehmed, Feyzi Effendi, Haznedarzâde Kadir, Imamzâde Hakkı, Haci Ahmed Arif, Yusufbeyzâde Adil, Yusufbeyzâde Sadık, Çarçi Hasanin Ali, and Hacimusaoğlu Haci Ömer.144 The deportation route led through Gürün and Akçadağ to Fırıncilar.

Armenians from five localities in the neighboring kaza of Bünyan – Bunyan, the seat of the kaza, with its 500 Armenians, as well as Gigi (pop. 350), Sarıoğlan (pop. 336), Seveghen (pop. 829), and Ekrek/Akarag (pop. 2,700) – were also deported toward Gürün on orders from the kaymakam, Nabi Bey, who held his post from 4 June 1915 to 31 August 1916.145

The Kaza of Kangal

In 1914, the kaza of Kangal had an Armenian population of 7,339; 1,000 of these Armenians lived in the administrative seat of the kaza, Kangal, from which they were deported in late June. The others lived in the district’s villages: Magahar (pop. 951), Yarhisar (pop. 703), Bozarmut (pop. 224), Komsur (pop. 343), and Mancılık (pop. 1,919).146 In the last-named village, the liquidation of the men took place in May and early June. One of the notables, Stepan Hekimian, was even nailed to a cross and paraded through the village. The execution of some 100 men in Daşli Dere was personally supervised by the leader of the squadron of çetes in Sıvas, Kütükoğlu Hüseyin. Among those killed were Murad, Asdur, and Hovhannes Karamanugian, Misak Dzerunian, and Vartan Stepanian. The rest of the population, including the men, was deported on 14 June. Only the 2,000 inhabitants of Ulash were temporarily spared, so that they could bring in the wheat harvest needed by the army. In September 1915, they were deported in turn toward the Syrian desert by way of Malatia, Adiyaman, and Suruc, on orders from the kaymakam, Mohamed Ali Bey, who held his post until 11 March 1917.147

The Kaza of Divrig

The administrative seat of this kaza, Divrig/Divriği, had a population of 12,000, almost one-third of whom were Armenian. Together with its 18 Armenian-inhabited villages, the district boasted a total Armenian population of 10,605.148 Among the countless vestiges of the medieval period sprinkled through the region was the monastery of St. Gregory the Illuminator, a jewel of medieval Armenian architecture build in the eleventh century that was perched on a rocky outcrop three hours north of Divrig near the village of Khurnavil (pop. 320). The neighboring village of Kesmeh (pop. 580), and the native village of the Noradounghians also boasted medieval churches, as did Zimara/Zmmar (pop. 1,250). Binga/Pingian (pop. 1,300), on the right bank of the Euphrates, was a medieval citadel that was nearly inaccessible because it was pressed up against a rock face close to the Euphrates. Its only access route ran over a suspended bridge that had been built in the eleventh century. In the southwestern part of the kaza was a string of Armenian villages on the two banks of the Lik Su: Arshushan (pop. 310), Kuresin (pop. 240), Odur (pop. 215), Parzam (pop. 510), and the village around the monastery of St. James that the Turks called Venk (from the Armenian word vank, monastery) (pop. 290). Finally, there were five Armenian villages on the right bank of the Çaldi çay, in the easternmost part of the district: Armdan (pop. 1,605), Palanga (pop. 480), Sinjan (395 Armenians), Mrvana, and Shigim.149 When the general mobilization order was issued, the recruits from the district of Divrig were assigned to an amele taburi based in Zara.150

In the administrative seat of the kaza, Divrig, the primate Krikor Zartarian was summoned before the kaymakam Abdülmecid Bey (who held his post from 1 March 1914 to 29 November 1915) in late March. Abdülmecid demanded that the weapons held by the Armenians in the town and the villages be handed over to him in one week’s time, along with the deserters. The Armenians’ response was apparently judged unsatisfactory, because the auxiliary primate, Father Serovpe Prigian, and several political leaders, such as Khachadur and Armenag Menendian; Garabed Hayranian; Mgrdich and Hagopos Kljian; Krikor, Dikran, and Mgrdich Kakanian; Melkon and Suren Guzelian; Mihran Doktorian; Kevork, Haig, Toros, and Tatul Hayranian; Nshan Tahmazian; Sarkis Lusigian; Hovhannes Shahabian; Khachadur Deombelekian; and Karekin and Aram Torigian, among others – a total of 45 people – were arrested, tortured for two weeks (some, including the auxiliary primate, died as a result), and then dispatched to Sıvas.151

The victims of the second wave of arrests were Divrig’s craftsmen and merchants, as well as its adolescents under draft age – a total of some 200 people. After being tortured for several days running, these men were taken from the village, tied up, and led an hour’s distance to the Deren Dere Gorge, where they were killed with axes. According to our witnesses, the men were all eliminated in this fashion, with the exception of 200 who managed to flee to the mountain villages inhabited by Alevites; some of them survived by pillaging Turkish localities in the region.152

The deportations from the kaza’s villages, however, did not begin until 28 May 1915. The peasants were first of all concentrated in Divrig, where the men and adolescents between the ages of 14 and 18 were separated from the others and confined in a church before being killed. The rest of the rural population was deported toward Malatia by way of Agn/Eğin and Arapkir.153 The townspeople of Divrig were put on the road a little later. On 28 June, the city was practically emptied of its men. On the morning of 29 June, the town criers announced the deportation order, which gave people three days to make preparations to leave. On 1 July, the Armenian quarters of Divrig were surrounded by regular troops who proceeded to expel the inhabitants. They were regrouped near the southwestern exit from the town and were dispatched from there toward Arapkir after the abduction of young women and girls for the harems of local dignitaries. The convoy was pillaged shortly after it set, at Sarı Çiçek, by Kurdish villagers from the surrounding area.154

According to Hmayag Zartarian, the anti-Armenian operations in the region were conducted by a squad of çetes commanded by Kör Adıl, a native of Trebizond. He was backed up by Çadıroğlu Abdüllah, Topcuoğğlu Hüseyin, Ğasab Süleyman Çavuş, Hafız Effendi, Leblebici Polis Mohamed, Köroğlu Polis Ülusi, İzet Bey, Sıvaslı Küregsiz Hafız, and others.155

We also know about the fate of the 1,300 Armenians of Binga/Pingian, located on the right bank of the Euphrates, thanks to the testimony of a survivor named L. Goshgarian. According to Goshgarian, 100 recruits from the village were put to work on the Erzincan- Erzerum road in a place called Sansa Dere, sharing the fate of the 4,000 to 5,000 worker-soldiers assigned to the amele taburis stationed in the region. However, a few dozen young men and adults did manage to flee to the mountains and go to Dersim. The rest of the population was deported toward Arapkir on 23 June 1915.156

The Kaza of Darende

In 1914, the kaza of Darende had a population of only 3,983 Armenians. Somewhat more than 2,000 of them lived in the seat of the kaza, also called Darende, while another 1,100 lived in the neighboring village of Ashodi.157 The kaymakam, Receb Bey, who had been appointed on 8 February 1913, was dismissed on 21 May 1915 and replaced by Süleyman Bey on 14 June. This might be taken as an indication that Receb refused to carry out Muammer’s orders. We do not know anything at all about the circumstances under which the Armenian population of the kaza of Derende was eliminated. The fact that it lies on the road between Gürün and Malatia, however, suggests that it was dealt a fate similar to that meted out to the Armenians of its northern neighbor.

The Kaza of Gürün

With its five exclusively Armenian villages and a handful of dispersed communities, the kaza of Gürün had a total Armenian population of 13,874 in 1914. The seat of the kaza, Gürün, isolated in a narrow, steep-sided valley, had 12,168 inhabitants, 8,406 of whom were Armenian. The town was strung out along the two banks of the Melos/Tohmak, made up of a succession of neighborhoods scattered through little valleys. The Armenians had 12 schools in Gürün. The town preserved its prestigious past, seen in the ruins of a medieval citadel that had been restored early in the eleventh century and the “desert” (monastery) of the Holy Mother of God in Saghlu. It was known not only for its commerce and craftsmanship, but also for the manufacturing of rugs, cotton fabric, and wool products. There were three Armenian villages in the immediate vicinity of Gürün – Kavak (pop. 220), Karasar (pop. 410), and Kristianyören (pop. 80) – and two more villages to the north on the road to Manclık: Karayören (pop. 560) and Çahırınköy (pop. 140).158

In contrast with what happened in many other regions, the kaymakam, Şahib Bey, who held his post from 30 August 1912 to 7 November 1915, does not seem to have played a determining role in the persecutions. According to Armenian sources, it was the military commander of Sıvas, Pertev Bey, who went to Gürün personally to transmit the order to begin the operations against the Armenian population. Avundükzâde Mehmed Bey, a Turkish notable from the town, and his three sons, Özer, Hüseyin, and Eşref, organized a meeting at which, with the help of the local Ittihadist club, a local branch of the Teşkilât-ı Mahsusa was formed under the name of Milli Cendarma. Captain İbrahimoğlu Mehmed Bey was appointed the commander of this militia. The group charged with carrying out the massacres and deportations brought together other notables who were members of the Young Turk club: İbrahimbeyoğlu Dilaver, Küçükalizâde Bahri, Eminbeyoğlu Mehmed, Mamoağazâde Emin, Köseahmedzâde Abdüllah, Sadık Çavuş, who was also the commander of a squadron of çetes, Yehyaoğlu Mehmed, Karamevlutoğlu Talât Effendi, and Nacar Ahmed Abdüllah Karpuzzâde.159 This committee charged Kâmil Effendi, the commander of the gendarmerie and a well-known Young Turk, with drawing up the lists of Armenian notables to be arrested. The first arrests took place in May. The first to be detained were the Armenian primate Khoren Timaksian and Reverend Bedros Mughalian,160 followed by the town’s notables, who were imprisoned in the Minasian khan, located in the Sagh neighborhood, and also in the Turkish baths at Karatepe. Delibekiroğlu Mehmed Onbaşi in particular was charged with supervising the torture sessions, which here too were designed to make the victims confess the location of possible arms caches and the nature of the “plot” they were supposed to have hatched.

The killing of the notables of Gürün began on 10 June 1915. Seventy-four men were massacred in the Ulash/Ulaş valley near the village of Kardaşlar by 12 çetes in gendarme’s uniforms under the command of Cendarma Ali Çavuş. On 27 June 40 more notables met the same fate near Çalikoğlu.161 On 22 June 1915, some 20 men were put to death on the road to Albistan by Tütünci Hüseyin Çavuş and his irregular troops.162 İbrahimoğlu Mehmed, the leader of a squadron of çetes, as well as Gürünlı Üzeyer Effendi, Ömer Ağa from Setrak (a village in Albistan), and Hakkı Effendi, a native of Ayntab, also played outstanding roles in slaughtering the males of the region of Gürün and then Akşekir.163

It would appear that the committee subsequently decided to have boys between ten and 14 arrested and killed. Kasap Osman, one of the Special Organization’s killers, indeed took on the job of dispatching a group of 120 boys to the valley of Saçciğaz, a Turkish village located two hours from Gürün, where they were slain with knives and axes.164

Küçükalizâde Bahri, one of the most influential members of the local Ittihad and the Milli Cendarma, personally murdered three of the principal Armenian leaders of the main town in the kaza – Hajji Hagop Buldukian, Hagop Shahbazian, and Haji Artin Gergerian – in Tel, near Aryanpunar. It was also Bahri who supervised the looting of the two convoys of deportees from the kaza in Kavak, a Turkish village located on the road to Albistan. Early in July, after the males were liquidated, the deportations were carried out under Bahri’s supervision with the help of local policemen (Abdüllah, Hamdi, and Sabri). Katırci Nuri Effendi, the inspector of the convoys, and Deli Bekir Mustafa, aided by Hacioğlu Yusuf, conducted the two convoys.165 The first passed through Albistan, Kanlı Dere, Kani Dağ, Ayranbunar, Sağin Boğaz, Aziziye, Göbeg Yoren, and Fırıncilar, and then through Ayntab, Marash, Urfa, and Karabıyık to Der Zor. The second convoy started off on the same route, but was then set marching in the direction of Hama, Homs, and the Hauran. Many of the deportees from Gürün were massacred in the vicinity of Marash.166

Deportations and Massacres in the Sancak of Tokat

The statistics compiled by the Patriarchate indicate that the sancak of Tokat had an Armenian population of 32,281 in 1914, which lived in 27 towns and villages that boasted 28 churches, two monasteries, and 14 schools with a total enrolment of 3,175.167 Thus, the Armenian presence in this western district of the vilayet of Sıvas was relatively modest, although, from an economic point of view, it was not negligible. Tokat, where the prefecture was located, was spread over a valley two kilometers long; its various neighborhoods lay on the sides of the valley, forming a sort of amphitheater. On the eve of the war, there were 11,980 Armenians and about 15,000 Turks in the city. But there were another 6,500 Armenians in the rest of the kaza of Tokat. They lived in 17 rural communities: west of the city, in the valley of the Tozanlu Su and on the plain of Ğanova, in Endiz (Armenian pop. 280), Gesare (pop. 100), Söngür (pop. 160), Varaz (pop. 90), Çerçi (pop. 220), Biskürcuk (pop. 550), Bazarköy (pop. 130), Kurçi (pop. 80); south of the city, in the Artova valley, on the road to Yeni Han, Bolus (pop. 300), Yartmeş (pop. 400), Kervanseray (pop. 350), Çiflik (pop. 326), Tahtebağ (pop. 262), Gedağaz (pop. 308); and, east of the city, near the road between Tokat and Niksar, in Krikores (pop. 600), on the left bank of the Iris, and on the right bank, Bizeri (pop. 280).168

The most striking event in the months preceding the outbreak of the war was the fire on 1 May 1914 that ravaged the street where many of Tokat’s businesses were located, Baghdad Cadesi. As we have seen, this was not an isolated act.169 There is even every reason to believe that these events reflected the general strategy adopted by the Ittihad in February 1914 with a view to diminishing the economic importance of the Greeks and Armenians. When the general mobilization was announced, many Armenians paid the bedel in order to avoid conscription; hence there were only 280 worker-soldiers from Tokat and Krikores in the amele taburi that was formed to build a barracks in the city. In line with directives issued by the Patriarchate, the military requisitions, despite the abuses to which they gave rise, did not occasion protests.170 The situation deteriorated in late April 1915, when the CUP sent its parliamentary representatives into the provinces of Asia Minor to preach elimination of the “domestic foe.” Several Armenian witnesses attended a meeting organized in the Paşa Cami at which a CUP representative attacked “those who, in our midst, seem to be friends,” but whom “the Turkish people must make it a priority to purge.”171 This declaration led the young Armenian primate, Father S havarsh Sahagian, to multiply gestures of goodwill toward the local authorities. The decree summoning the population to turn in all the weapons in its possession, pasted up in every public building, compelled the primate to organize a discussion with all the community leaders. According to Hovhannes Yotghanjian, who took part in this meeting, all were aware of the impending threat, but there was disagreement as to what to do about it. Shavarsh Sahagian and the local Hnchak leader M. Arabian were opposed to giving up the weapons and suggested taking measure to organize the self-defense of the Armenian neighborhoods. A majority of those present, however, pointed out that there were no Armenian fighters available in the city apart from a few deserters who had taken refuge there. The weapons were finally deposited in the Church of St. Stepanos and delivered up to the authorities.