Financial viability means that the project generates sufficient income to cover its costs and to produce a return sufficient to attract investors and to compensate the developer. The need to ensure the project’s financial viability affects every decision a developer makes about the project, from initial conceptual planning to detailed operations. A terraced rooftop park at Namba Parks in Osaka, Japan, lowers the costs of cooling the center while functioning as an attraction for visitors.

The financing of any real estate development project depends, first, on its financial viability and, second, on its financing structure. In turn, retail development has certain distinctive characteristics that shape how the viability and structure are determined.

Financial viability measures how much income the project generates compared with its cost. Good developers learn how to assess a project’s financial viability right from the start as part of land acquisition and continue to evaluate viability as new information emerges and as decisions are made throughout the development process. Income for the real estate product comes from market support, either from sales or lease revenue. Costs include predevelopment, construction, financing, marketing, operations, and ongoing management. How the real estate developer estimates and communicates the viability of a real estate project determines whether it can attract the capital necessary to proceed.

The financing structure of a retail project depends on how the development entity is organized, the sources of capital, and conditions in the capital markets. The development entity may be an individual, a partnership, a corporation, a limited liability corporation (LLC), a real estate investment trust, or a joint venture of any of these entities. Frequently, a joint venture arrangement between an investment source and a development entity provides the structure for investment in a project. Regardless of how the development entity is organized, however, for new development a developer’s reputation and credibility with capital sources are the single most important factors influencing whether a project can be financed.

Sources of capital typically divide into two types: at-risk “ownership” or equity investment, and interest-bearing loans (debt) secured by the value of the real estate assets. The cost of capital depends on conditions in the capital markets such as the liquidity of the markets and the relative returns on real estate investment compared with competing investment classes such as stocks and bonds. These conditions are constantly changing in a dynamic market, thus affecting the availability of financing for real estate projects and the specific instruments by which equity investment and loans are conveyed.

Finally, retail development is different from other real estate developments in its dependence on achieving a successful merchandising mix of tenants. A retail center’s identity in the market and its success in attracting customers depend on having the right anchor tenants, if it is an anchored center, and the right mix of other smaller tenants. For an anchored center, a developer needs to secure commitments from major tenants before funding will be approved. For an unanchored center, the developer usually needs a significant volume of preleasing commitments from smaller tenants. The effort to sign up these smaller shops must take into account how the mix contributes to the retail center’s attractiveness to customers. Because of their importance to the developer’s success in obtaining financing, established retail tenants, especially national brands, exercise a great deal of influence over a project’s design and management. In the case of larger retail projects (which usually have multiple anchor tenants), the retail developer must learn how to work with and accommodate the interests of multiple strong personalities to put together a successful project.

Managing construction scheduling and phasing is also important to a center’s financial success. Large anchor tenants frequently try to “launch” at certain times of the year (before the April or December holiday seasons, for instance), so meeting these opening windows may be a requirement for the start of lease payments from some tenants. Other retailers may delay making lease commitments until construction is complete, thus delaying the start of income generation. Sometimes it is appropriate to leave outlying pads or ancillary phases of the center for construction until after the center opens and a customer flow is proved, often enhancing their attractiveness to higher-rent tenants.

Even when construction schedules are met, a significant portion of a retail project may not be fully leased at opening, thus requiring that the cost of negative cash flow during the lease-up period be included in the financing program. Sometimes a developer decides that the appropriate leasing strategy requires waiting for the right mix of smaller tenants, thus extending the period of negative cash flow. Usually, this period is one or two years, depending on the market and the extent of pre-leasing commitments.

This chapter explains all these issues in more detail. It explains the various ways of measuring financial viability and how the developer must document and justify this viability to capital sources. It explains how development entities are organized and the options that these entities have for accessing capital sources. And it describes how the distinctive characteristics of retail development affect financial viability and structure in terms of project feasibility and ongoing management.

First, a word about terminology. Just like other areas of human endeavor, real estate financing has its own terminology. Shorthand terms of the industry include words and abbreviations like waterfall, pari passu, recourse, cap rate, DCR, LTV, mezzanine, promote, and many more. They can be bewildering and intimidating, especially to a beginning developer. And frequently in the real world, different terms are used for the same concept. So understand the concepts and pick up as much of the terminology as possible, but do not be intimidated by terminology in the real world that you do not understand. You should never allow unfamiliar financial terminology to obscure your understanding of the concept.

Financial viability means that the project generates sufficient income both to cover its costs and to produce a return sufficient to attract investors and to compensate the developer. The project’s financial viability affects every decision that a developer makes regarding the project, from initial conceptual planning to detailed operations.

To evaluate a project’s financial viability, begin with an understanding of the income sources that a real estate project generates. Retail projects generate, primarily, lease income in the form of rent from retail tenants. Sometimes the sale of pads to larger anchor tenants or to other outlying users can be credited immediately against costs, or recurring income accrues from such sources as corporate sponsorships, parking, and advertising. But ongoing income from leases is usually the primary source of value in a retail project.

Once project income is understood, costs should be evaluated. Land, predevelopment expenses, off-site improvements, fees and exactions, construction, marketing, financing, ongoing operations, and management all contribute to project costs, and each category of costs has its own hazards for misestimation.

When income and costs are known, then a project’s financial viability can be evaluated in conventionally accepted ways: measuring project value by applying a capitalization rate (or cap rate), calculating leveraged and unleveraged internal rate of return, and evaluating project value through application of project hurdle rates.

Notes

a. 5 percent over $300 per square foot.

b. 6 percent of inline shops and inline shops’ share of recoverable operating expenses.

The market determines how much a project can charge in rent; thus, to estimate income the developer needs to know the market and, most important, how to respond to market opportunity. Because success in retail development depends so much on tenants, conceptualizing a project is frequently an iterative communication process in which the developer balances market potentials with available and interested retailers, development concepts, and available sites. Ultimately, it is the market and the developer’s talent and skill in conceptualization at this early stage that determines whether a project is possible.

Because the merchandising mix is so critical to the success of a retail project, responding to the market means envisioning the tenant mix. Who are the major tenants? What is the product mix of the smaller tenants? What is the customer profile? To answer these questions, the developer needs good communication with retailers and an understanding of their preferences for customer profiles, location, and cotenancy. The developer needs firsthand familiarity with the local market, customers’ characteristics, competitors, and prices. All this effort goes into determining the project’s merchandising mix, which then leads to a determination of its location and scope, square footage of leasable space, amount of parking, and configuration on the site. The process of center visioning also requires the talents of brokers, market experts, architects, and site planners, though it is also important to minimize the cost of outside services at early stages (see “Funding Predevelopment Costs” below).

After determining the scope, the developer then looks at total rental income for each category of space. Larger spaces with anchor or major tenants usually have lower rents per square foot or are sold as pads. Income comes in the form of minimum or base rents, percentage rents, and recoverable operating expenses; it is expressed initially in the form of the first year of stabilized income (that is, the first year of full occupancy by long-term tenants).

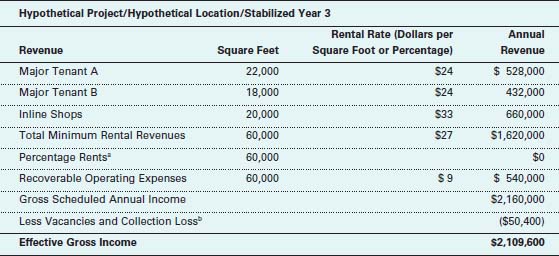

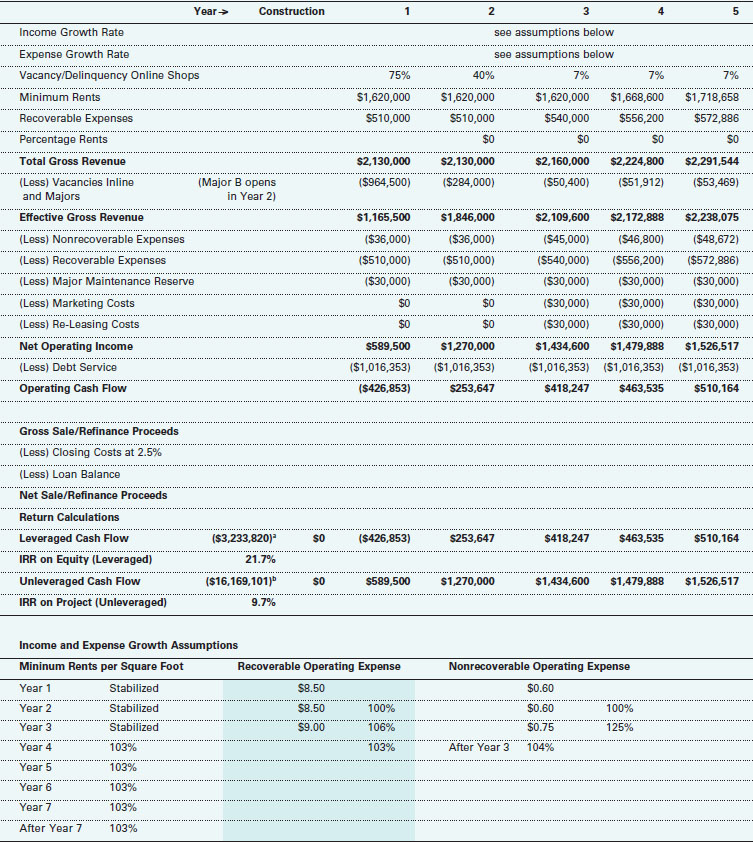

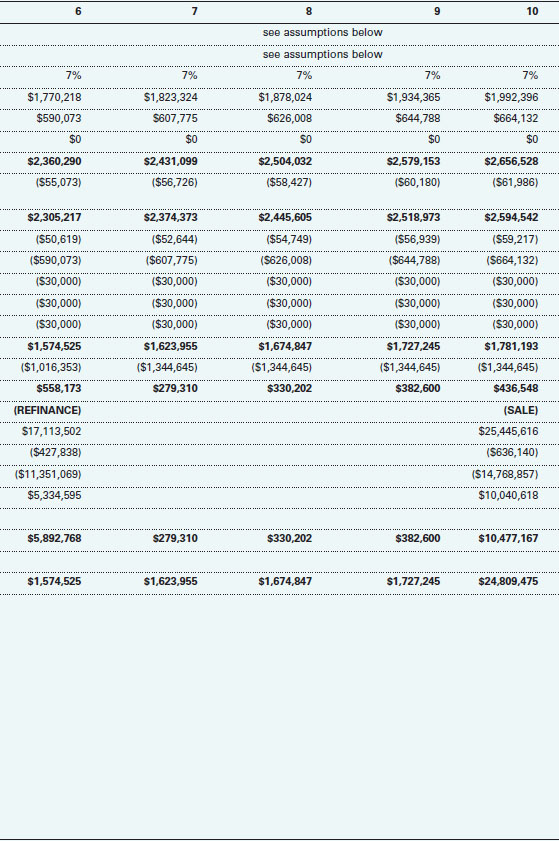

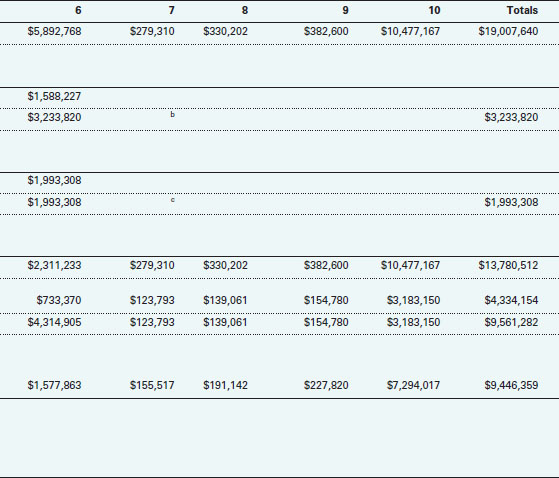

Figure 3–1 shows the format for a typical income statement for a retail project of 60,000 square feet (5,575 square meters), which we will call Hypothetical Project. We will follow this project through the steps required to evaluate its financial viability, resulting in a profit distribution scenario based on a possible financing structure.

In the determination of financial viability, these assumptions need to avoid speculative income or income based on favorable conditions that may or may not occur. Such income may provide “upside opportunity” to investors and to the developer but should not be considered in the initial determination of viability. For this reason, percentage rents are listed as a line item but not included in the projection.

The main source of ongoing income is covered in tenant leases— minimum or base rents, percentage rents, and recoverable operating expenses. Rent is charged per square foot and varies by type and size of tenant, its location in the project, and its bargaining strength. Pictured: Twenty Ninth Street, Boulder, Colorado.

Rents in this example are expressed as dollars per square foot per year. In many markets, they are expressed as income per square foot per month.

Minimum rental revenues are shown after subtracting leasing commissions and occupancy costs; in general, they need to reflect income available to the project owner to pay expenses that are the owner’s responsibility. The vast majority of retail projects use triple net rents (frequently called NNN in pro formas), which exclude the three major occupancy costs—property taxes, maintenance, and insurance.

Most retail projects recover a portion of their operating expenses by charging an additional rent called recoverable operating expenses. In Figure 3–1, this revenue is shown as a separate category paid by tenants in addition to their base rents. These charges typically include property taxes, property and liability insurance premiums, and common area maintenance (CAM) charges, but they could also include such items as utilities sold or furnished to tenants and security. All these charges need to be evaluated from the point of view of the market and acceptability to tenants. Not all tenants pay the same CAM charges: some larger and more desirable tenants receive a discount.

Most retail projects also charge an additional category of rent called overage or percentage rent—that is, an additional rent over the base rent, usually a percentage of retail sales over a certain level (see Chapter 7 for a detailed discussion of percentage rent). Although individual leases indicate a gross sales volume as the breakpoint (the amount above which the percentage rent is applied), Figure 3–1 show a centerwide sales figure per square foot ($300) as the breakpoint. An average retail center has sales of $300 to $400 per square foot ($3,230 to $4,300 per square meter). In most cases, management charges an additional rent of 5 to 10 percent for sales over the specified level, with different percentages for higher levels of sales. This percentage rent is beneficial to tenants, because it gives the project owner an incentive to help them succeed. Because they depend on favorable conditions that may or may not occur, percentage rents are not included in the financial analysis for viability or capital funding, and Hypothetical Project does not include percentage rents in the first year of stabilized income.

Also not included in the income estimate are individual deals with tenants for extra tenant improvements beyond the basic tenant improvement allowance. Such extra tenant improvements can include finishes such as counters, racks, and carpeting in individual stores for one tenant that not all tenants receive. These arrangements pay for improvements beyond the allowance for basic tenant improvements that the developer funds as part of construction costs, usually $10 to $15 per square foot ($108 to $160 per square meter). Tenant improvements beyond this basic allowance usually are the responsibility of individual tenants, but sometimes an individual, highly desired tenant can negotiate a higher contribution from the developer for tenant improvements. Retailers with good credit ratings can also negotiate for higher tenant improvement allowances or ask the developer essentially to serve as a source of financing for improvements. Under these circumstances, the developer installs the improvements and then amortizes some or all of the extra costs with higher rent. This arrangement adds to the developer’s requirement for capital, but the income associated with the extra rent should cover the cost of the additional financing. This income source is not included for Hypothetical Project, because it usually is a self-funding component of the project. Tenant improvements over the basic allowance are usually financed with a layer of financing separate from the basic project financing (see “Other Types of Debt” below).

The estimate of income in Figure 3–1 includes an allowance of 6 percent for losses from vacancies and uncollected rents for the inline shops—that is, a reduction of 6 percent in estimated income for the portion of the project comprising nonmajor tenants. Usually, no vacancies are assumed for income from major tenants, because they are larger, more creditworthy, and more reliable in meeting their long-term lease obligations. This allowance is a judgment call based on market conditions and may be higher or lower, although 6 to 7 percent is considered the industry standard.

Note that the estimate is made for stabilized Year 3, when a project typically has achieved full occupancy. Higher vacancy levels often occur in the first two years of a project’s operation, for which some negative cash flow probably needs to be financed.

Finally, note that the revenue estimate in Year 3 does not include rent increases scheduled for later years (the full cash flow pro forma for later years is discussed below). For now, we are focusing on the first stabilized income year as the basis of evaluating the project’s value.

Two kinds of costs must be estimated: 1) all the costs of building the project (land and construction, for example) and 2) annual operating expenses.

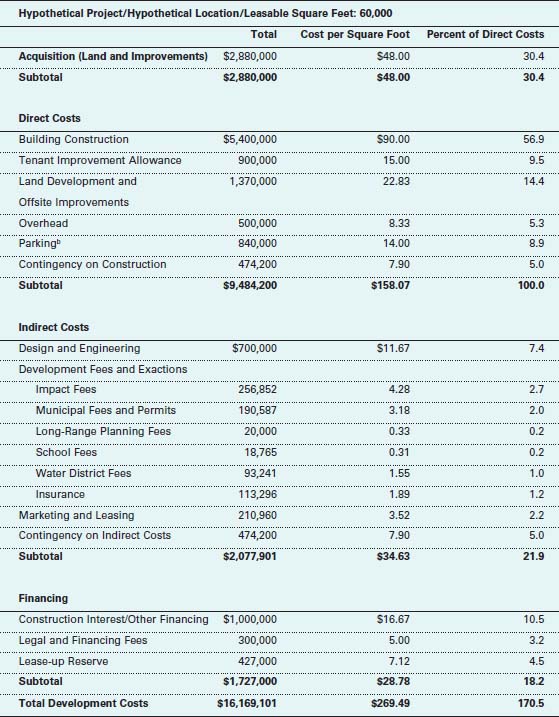

Figure 3–2 shows an initial estimate of construction costs for Hypothetical Project for which income was estimated in Figure 3–1. Figure 3–2 shows numerous categories of costs, with total development costs more than 170 percent of direct costs.

Make sure that all cost categories are addressed, including site development, parking, design, marketing, and construction financing. Beware of “all-in” estimates, and do not assume that all categories are addressed. Every source of information includes different categories in its estimate. Include the major players on the development team such as contractors and the architect in putting together the estimate. A considerable amount of research and knowledge is necessary to estimate these costs, including knowledge of construction, financing, services, and government fees and exactions.

Note that project costs show a lease-up reserve of $427,000, which is equal to the negative cash flow associated with the year after construction is complete during which the project is leased. To the extent that lenders approve including this first-year deficit in project costs, the sponsor will be able to finance this deficit from permanent project financing.

It is extremely important that development costs not be underestimated, as lenders typically are not amenable to revisiting lending requirements. As a result, it is better to be conservative and err on the side of higher rather than lower costs in the early stages of determining project feasibility. It also means including an adequate contingency in the budget at the early stages to protect the analysis of viability from coming up short. Figure 3–2 shows contingency costs in both hard (direct) costs and soft (indirect) costs. These line items in the budget are important to maintain because funding sources will monitor the expenditures-to-budget performance as the project proceeds.

As the project goes to financing, it is important to recognize that cost overruns in the budget will most likely be the developer’s responsibility. Estimating costs too low can be very expensive.

Figure 3–3 estimates annual operating expenses and net operating income (NOI) for Hypothetical Project.

Operating expenses include all maintenance, management, property taxes, and insurance, some of which can be recovered from tenants and some of which cannot. Because tenant turnover is inevitable, the project also estimates expenses for re-leasing space (the cost of replacing existing tenants with new tenants). The budget also includes ongoing marketing costs as well as an annual replacement reserve for periodic major maintenance (usually $.50 to $.75 per square foot [$5.40 to $8.05 per square meter]) such as reroofing the buildings or resurfacing the parking lot. Frequently, CAM charges amortize some portion of major maintenance and marketing costs.

Notes

a. Allocation based on leasable square feet.

b. 240 stalls at $3,500 each.

Subtracting the annual operating expenses in Figure 3–3 from the effective gross income in Figure 3–1 yields net operating income, a fundamental parameter of financial viability for a retail project. It generally is expressed as the following formula:

Effective Gross Income - Operating Expenses = Net Operating Income (NOI)

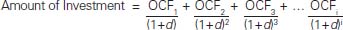

NOI is distributed between repayment of debt and return to equity investors and the developer. The adequacy of NOI to meet these two demands is evaluated by comparing the project valuation at a “capitalization rate” with the costs of the project. A capitalization rate (or “cap rate”) is an indicator of current market conditions for the availability of capital and a project’s perceived price appreciation.

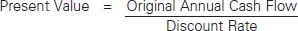

Before we evaluate Hypothetical Project, we need to consider what a capitalization rate actually measures. Theoretically, a capitalization rate is equivalent to the “discount rate” that results from calculating the present value of an equal annual stream of cash flows over an infinite period. As an example, a cash flow of $1,000 per year discounted at a rate of 8 percent has a present value of $12,500 over an infinite period. Arithmetically, the present value of an equal annual periodic cash flow at a specified “discount rate” over an infinite period is expressed as:

The cap rate is a term-of-art in the real estate business that is, in effect, an “all-in” way of calculating project value. Conceptually, it derives from the formula above, calculating the present value of an annual cash flow that is received in perpetuity, but it differs technically from the discount rate in that it narrowly measures only the periodic return of investment from equal periodic payments, while the discount rate more broadly measures the return on capital investment that results from future project payments that may or may not be equal and could or could not be periodic.

Cap rates vary with the investment climate and reflect market conditions for competing investments and liquidity of capital. In general, higher cap rates are associated with capital markets with high costs of capital and low perceived potential for appreciation, thus resulting in lower property values. Low cap rates characterize the inverse circumstances, that is, low costs of capital and high perceived appreciation. Another way to look at cap rates is that they are the inverse of an earnings multiple; for instance, a cap rate of 5 percent is the inverse of an earnings multiple of 20. Higher cap rates mean lower earnings multiples with lower property values, and low cap rates mean higher earnings multiples and higher property values.

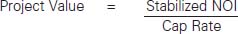

The fundamental formula for valuing a retail project based on a stabilized NOI is as follows:

For the retail sector in the 1990s, cap rates ranged from 8 to 12 percent, depending on the region. In the first decade of the 2000s, reflecting investors’ preference for real estate and the high liquidity in capital markets, cap rates have dropped for most categories of retail development to 6 to 8 percent, levels currently comparable with cap rates for industrial and multifamily for-rent housing.

In general, cap rates are correlated with other market indicators such as ten-year Treasury inflation-protected securities or ten-year Treasury bonds. Information on current market cap rates is available from numerous sources, including market newsletters from private sources such as the Appraisal Institute and Real Capital Analytics, or from Web sites such as the one maintained by the National Council of Real Estate Investment Fiduciaries.

Although a fundamental metric of real estate transactions, cap rates, because they measure valuation based on one year’s NOI, are limited in measuring a development project’s financial viability. A more comprehensive measure of viability is internal rate of return (see “Measuring Project Return” below), which measures the total return of a project, either leveraged or unleveraged, over time.

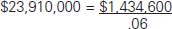

In the case of Hypothetical Project, Figure 3–3 shows NOI of $1,434,600. Figure 3–5 shows the calculation of project value based on the assumption that market conditions are valuing projects at a cap rate of 6 percent. In other words, market conditions at this cap rate are such that if the project were built and leased as planned, then it could theoretically be sold for about $23.9 million. Compared with the costs of development shown in Figure 3–2 (about $16,169,100), this project looks like it could produce a “profit” of about $7,740,900 (see Figure 3–5). In other words, if this project were built at the assumed cost, leased at the assumed rates, and sold at the cap rate existing in the current market (as shown in Figure 3–5), it would produce a return on costs of about 47.9 percent.

Whether this “surplus” provides sufficient viability to attract the capital to develop this project is discussed in more depth below under “Measuring Project Return” and “Financing Structure.”

Some portion of project costs is usually financed with debt (that is, an interest-bearing loan secured by a lien on assets, usually the project itself), and the remainder is funded from an equity investment from two sources: outside investors and developer capital.

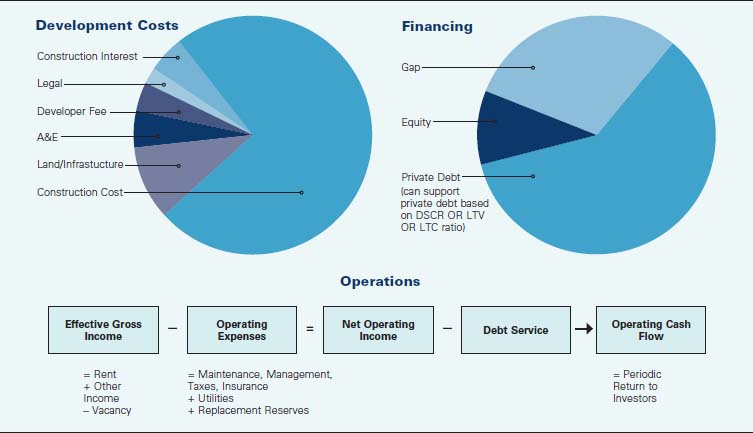

Developer capital includes all funds required for the organization and operation of the project, net of third-party financing from lenders and outside equity investment. Before the start of construction, developer capital usually, though not always, covers predevelopment costs (see “Funding Predevelopment Costs”). Developer capital could be used for predevelopment costs, contributed land, and the developer’s coinvestment to satisfy the requirements of outside third-party investors that the developer is adequately vested in the project. Usually, the developer advances initial funding to the project and may get reimbursed for a portion of these advances when the loan and equity investors provide their funding. Figure 3–6 shows this basic funding structure.

Debt usually is repaid monthly, usually at a fixed interest rate, in equal monthly amounts designed to amortize the principal amount of the loan over a repayment period at a fixed or variable interest rate. Return to equity investors and the developer is paid after loan obligations are met; they vary with the project’s profitability. Because debt payments are secured by liens on assets, the interest rate paid on debt is lower than the return commanded by investors and developers on at-risk equity and developer capital.

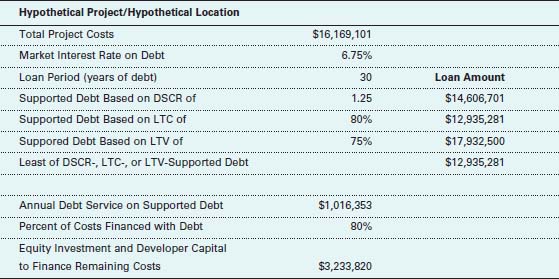

The relative amount of debt in a project typically varies with the financial strength of the developer and the strength of the project itself. The basic determinant, though, of how large a loan a project can support is usually some combination of the debt service coverage ratio (DSCR) and loan-to-cost (LTC) or loan-to-value (LTV) ratios.

The DSCR is the ratio of stabilized NOI to annual debt service. Most lenders evaluate a project and lend only when the DSCR meets an underwriting criterion of 1.15 to 1.30. Depending on general conditions in the capital markets, a strong project sponsored by a strong development entity may qualify for a DSCR at the lower end of the range. LTC and LTV are also underwriting criteria that will also affect how large a loan a project can receive. LTV ratios range from 60 percent to 80 percent of value. LTC ratios range from 65 percent to 80 percent of costs. Unless a development entity is particularly strong, it usually is limited to the lower of these three ratios at a percentage of no more than 80 percent of costs.

FIGURE 3–7

After paying debt service, the annual cash flow remaining is called the operating cash flow (OCF), which is available for distribution to investors and the developer. OCF must be sufficient to repay equity investors and provide an adequate return to the developer.

In general, a developer normally attempts to get as large a loan as the project can support to minimize the share of the project financed with equity investment. This strategy is called leveraging; it involves minimizing the at-risk equity investment required so that project returns service a smaller investment. With a greater percentage of the project financed with debt, which carries a lower interest rate and a longer repayment period than the return required for equity, the return to equity is higher. Some equity investors such as pension funds, which are particularly risk averse, avoid high leverage to minimize the potential for having to put cash into the project to service a loan if income should drop.

Figure 3–7 summarizes the discussion to this point about the basic financing structure for real estate development and ownership, including NOI, debt, equity, and OCF.

Note that in Figure 3–7, the component of financing that is uncovered by debt or equity is called the gap. Figure 3–7 shows this component for conceptual purposes, as most projects will not proceed with an unfunded gap. If the gap is a short-term phenomenon, however, it may be covered with some combination of participating or mezzanine debt (see “Other Types of Debt” below).

Figure 3–8 shows a funding program of debt and equity for Hypothetical Project based on the previous development costs and NOI calculations. The loan is constrained to be the lesser of debt supported by a DSCR of 1.25, an 80 percent LTC, or a 75 percent LTV ratio. Because the LTV and DSCR ratios result in higher loan amounts than the LTC ratio, the loan is constrained to 80 percent of costs. The remaining project costs are funded with an equity investment and developer capital.

Note the debt repayment terms assumed in Figure 3–8. The interest rate is 6.75 percent, with a 30-year amortization of the loan. Even though it is typical for such a loan to require a ten-year repayment period, the amortization period and interest rate are much less costly than the return to equity requirement of 15 percent or greater, where the principal repayment terms require return of principal as a first priority out of OCF. Now let us examine how total project return is evaluated.

The internal rate of return (IRR) measures the total profitability of a project over its entire holding period. Unleveraged IRR measures return on total project costs, leveraged IRR measures return on equity investment, and developer capital takes into account the portion of project costs financed with debt.

FIGURE 3–8

IRR is the discount rate that, when applied to the project’s income flow, results in a net present value equal to the amount of the investment. In other words, it is the discount rate (d) solved for in the following net present value equation, where the time periods go from Period 1 through i.

Solving for the IRR is an iterative algorithm that calculates and recalculates net present value by trying values of d and going higher and lower in smaller increments until the present value of the stream of OCFs and proceeds from capital events equal the amount of the investment. Calculating IRR with a modern financial calculator such as a Hewlett Packard 12c is relatively simple. With a spreadsheet program such as Excel or any of a variety of commercially available real estate analysis packages such as Argus, it is simpler still.

Figure 3–9 shows the calculation of IRR for Hypothetical Project, arriving at a leveraged IRR of 21.7 percent based on the assumptions. The leveraged IRR is the return on the $3,223,820 of equity investment and developer capital, which is shown in Figure 3–8 as 20 percent of costs, where costs include the first year deficit in OCF.

Figure 3–9 illuminates some previously undiscussed financing concepts typical of a retail project. First, note that part of the leveraged return is based on a “refinancing” of the project at Year 5. This capital event is similar to taking equity out of one’s house through refinancing. As the NOI becomes established and can support more debt, the refinancing permits the owner to pull cash out of the project through refinancing. A second capital event occurs when the project is sold in Year 10, or at the end of a planned “holding” period. Most equity investors need to have a planned holding period at the end of which their investment is liquidated. Note that construction is assumed to be one year in duration and is included as a period in the calculation, recognizing that the investment will need to provide return for this period as well as when the retail center is actually operating.

Also note that the assumed cap rate for which the sale occurs at the end of the holding period is 7 percent, a full 1 percent higher than the current rate. In general, financial viability is based on two cap rate assumptions: an initial (or going in) cap rate and a terminal (or going out) cap rate. The initial rate reflects the value of a project under current market conditions in its current physical condition. Hypothetical Project is new and consequently in excellent condition. The terminal rate is projected as higher, not necessarily because the market is projected to change but primarily because it is based on the reality that the project will have depreciated and may have some characteristics of obsolescence as a result of its age.

For the redevelopment and expansion of a 1950s community shopping center, the developer’s equity contribution was internally financed. Pace Properties, the developer, offered the family trust that owned the old strip center the option of selling its property. The trust chose instead to contribute its equity investment in the property, and Pace formed a limited liability corporation with the family trust. The new Brentwood Square has three times the square footage of the older center.

The unleveraged IRR on the project is 9.7 percent. This figure is the return on total project costs, treating NOI as OCF—that is, as though the project were financed with all equity and no debt. The unleveraged return is based on NOI through Year 9 and the capital event of a sale in Year 10. Proceeds of the sale are net of commissions. The unleveraged IRR on projects is the rate of return that is usually quoted by market data services and is usually available from the same market data services that provide information on interest rates and cap rates.

In our example, the 9.7 percent unleveraged and 21.7 percent leveraged IRR on investment at the present time would probably be sufficient to attract equity and developer capital, depending on the credibility and reliability of the development entity. Although modest rent increases of 3 percent per year after Year 3 are included in the projection, the upside potential of percentage rents is not projected in these cash flows. If the project succeeds and hits percentage rents, the returns could be higher.

The dynamics of profit distribution, preferred returns, and promotional distributions are discussed in “Financing Structure.”

Before we leave this discussion on assessing financial viability, we will discuss ways of assessing the financial viability of a development opportunity, especially at the early stage of land acquisition, short of a full-scale cash flow analysis such as shown in Figure 3–9. This skill is particularly important during land acquisition, usually the earliest stage at which the developer must evaluate viability.

The only decision in a development process that the developer has complete discretion over is whether to acquire a piece of land at the price at which it is offered. If the price is too high, the developer should not acquire the land. How does a developer know whether a particular piece of land is affordable?

Land is only as valuable as the use to which it is put, so the starting point for land valuation is an economic determination of residual land value, the value at which the price of land supports a return on the project sufficient to attract investment and compensate the developer.

The simplified analysis of residual land value relies on the calculation of the project’s value by applying a cap rate to a stabilized NOI. It also blends the cost of debt capital and the cost of required investment return to hypothesize a blended cost of capital through the point at which stabilized NOI is achieved. For example, if a project needs to produce a 12.5 percent blended annual return to attract capital (both debt and equity) and provide adequate return to the developer and it will need three years from the start of construction to achieve a stabilized NOI, then a simplified calculation of the total return needed to that point is 12.5 percent compounded over three years, or about 42.4 percent. This minimum desired total return is called the project hurdle rate and is used to assess financial viability at the early stages. Note that the determination of the hurdle rate is sensitive to the construction and lease-up period as well as the probable mix of debt and equity in the project and the developer’s desired objectives for income. If equity is a higher percentage of funding, then the hurdle rate may be higher to reflect the higher returns that this funding source requires. Moreover, for costs incurred before the start of construction, the requirement for rate of return on equity needs to be significantly higher for this portion of the project costs, thus raising the hurdle rate to reflect the degree of risk during predevelopment. (“Hurdle rate” is a generic term that can apply to many different aspects of financing—a threshold that must be met or exceeded for a development opportunity to be considered acceptable. For instance, investors frequently talk about a hurdle rate for minimally acceptable IRR on a project.)

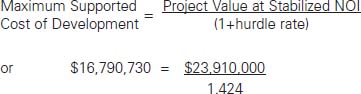

For Hypothetical Project, we previously determined that project value at stabilized NOI was:

If the hurdle rate for Hypothetical Project is the 42.4 percent calculated earlier, then the maximum development cost that this project will support is as follows:

In other words, the developer can afford to build this project for a maximum cost of about $16,790,730 and still have sufficient return at the point of stabilized NOI to be able to attract capital to the project and receive adequate compensation for the time and skill that the project will require from the developer.

Note, however, that this analysis tells the developer what the land is worth at the point when it is fully entitled. In other words, if the developer must pay for the land before this point, the land value is less to reflect the risk and carrying costs for closing before entitlement. The evaluation of the risk before entitlement depends on the circumstances of a particular site. Carrying costs will probably be quite high, partially a reflection of the risks of entitlement and partly a reflection of low valuation and thus limited borrowing capacity for unentitled land.

Notes

Based on 60,000 square feet of leasable area.

Marketing in first three years included in development costs.

Re-leasing costs based on 25 percent turnover every five years.

Sale at Year 10 based on cap rate of 1 percent higher than current cap rate.

a. Initial equity investment.

b. Total investment.

Waterside at Marina del Rey is on a ground lease from Los Angeles County, which owns all the property in Marina del Rey. In return for a significant new term in the ground lease before renovation of the center, the county received a commitment from Caruso Affiliated on its expenditures to renovate the project. In the end, the developer spent more than twice its obligation in the renovation.

Residual land value is a simple calculation. It is the cost obtained by subtracting all the nonland costs from the total maximum allowable cost or, in this case, about $3,501,600 (see Figure 3–2 for cost data). In other words, the developer could afford to pay about $3,501,600 for land.

In fact, note that the total development cost for Hypothetical Project is below $16,790,730 by about $622,000. The land cost for Hypothetical Project was also estimated at $2,880,000, about $622,000 less than what was deemed “affordable.” In other words, it looks as though the developer of Hypothetical Project paid less for the land than was theoretically affordable. If the hurdle rate analysis says that the project can afford more than the land actually costs, take the lower price! The analysis is designed only to prevent paying too high a price. This same viability analysis can be applied to evaluate the impact of any component of project costs.

A development entity can be an individual, a partnership (general or limited), a corporation, a limited liability corporation, a real estate investment trust, or a joint venture among any of these forms of entities. With the increased involvement of pension funds, insurance companies, private equity funds, and REITs, the complexity of the organization of development entities has increased significantly.

Three major factors have affected the way development entities are organized: taxes, personal liability, and liquidity. In general, real estate entities try to avoid the double taxation of profits characteristic of many corporations that pay their own taxes, with any dividends distributed to shareholders taxed again, a significant disadvantage to this form of ownership. Insulating shareholders against personal liability, the second factor, for the operation of the development entity is a primary advantage of the corporate form of organization, however. The corporation also has an advantage in raising capital. If it is large enough, then it can sell shares to the general public, thus creating a broader source of capital and, consequently, a much larger scale of operation. Each form of organization has advantages and disadvantages in addressing these three factors.

To avoid double taxation, many real estate entities are organized as partnerships. A partnership is a reporting vehicle; it is not a taxable entity because partnerships are not considered separate entities for tax purposes. Therefore, all income and appreciation flow through to the investors, and income is taxed only once, when an investor receives it.

In a general partnership, all the partners share the risks, rewards, and management of the venture. Any and all partners are liable (jointly and severally) for all the debts and obligations of the business. For this reason, wealthy individuals and money partners do not typically enter into general partnerships for real estate ventures, preferring the protection of limited liability provided by limited partnerships or limited liability companies.

The funding of The Greene in Beavercreek, Ohio, involved a three-part agreement among the city of Beavercreek, Greene County, and the developer. This partnership, facilitated by a community economic development agreement, generated the issuance of $14.8 million in municipal bonds for the public infrastructure of the project.

Limited partnerships are historically the most widely used form of ownership for retail properties. A limited partnership must include at least one general partner and one limited partner, with the general partner (or partners) liable for the partnership’s debts and other obligations and the limited partner (or partners) bearing no liability beyond contributed capital. Participation by limited partners in the day-to-day management of the partnership is not allowed, and if it occurs, the limited partners risk loss of their limited liability status. For retail developments, the most common type of limited partnership involves a corporate entity established by the developer, which acts as the general partner and manager, and investors, who are limited partners.

Limited liability companies—relative newcomers to the scene—combine the advantages of a nontaxable entity, limited liability for investors, and no restrictions on investors’ participation in the management of the enterprise. They also have considerable streamlined provisions for governance. Virtually every state has adopted legislation that allows business organizations to be formed as LLCs.

In general, the members and managers of an LLC are not personally liable for the LLC’s debts and obligations, regardless of the degree to which they participate in its management. A member’s liability is limited to the amount of capital contributed. Accordingly, creditors may not recover any part of a claim from a member’s personal assets if the LLC’s assets are insufficient to satisfy it.

The advantages of LLCs—flexibility in allocation of income and loss, flow-through tax benefits, limited liability, streamlined governance, and owners’ participation in management—make this form of ownership increasingly attractive for retail development and investment. Currently the LLC form of ownership appears to be supplanting the so-called “S” corporations, which have the flow-through benefits of the LLC but are encumbered with the governance burdens common to corporations.

One measure to broaden the pool of investors has been the REIT, especially publicly traded equity REITs. To qualify as a legal REIT entity, a company must invest in real estate assets and distribute at least 90 percent of its taxable income to its shareholders annually, which in turn qualifies the REIT to deduct dividends paid to its shareholders from its corporate taxable income. Thus, most REITs pay little or no corporate tax, which makes them attractive to investors, compared with other publicly traded companies.

REITs, especially publicly traded equity REITs, have substantially enhanced liquidity for real estate investment. As of the end of 2004, about 24 percent of equity REIT capitalization was in retail real estate, with about 46 percent of that in shopping centers, 47 percent in regional malls, and a small amount in freestanding retail buildings. REITs provide small investors with an opportunity to invest in managed real estate, to spread risk through diversified holdings, and to acquire interests in properties that would ordinarily be beyond their means. Because REIT shares can be easily sold or transferred and thus are more liquid than other types of real estate holdings, REITs have substantilly enhanced liquidity for real estate investment.

In recent years, some REITs have used various forms of partnership structures to acquire properties and to combine the capital-raising ability of a REIT with the tax and ownership advantages of a partnership. Umbrella REITs (called “UPREITs”) and downREITs use REIT capital to make limited partnership investments in property owned by a separate or subsidiary partnership. These variations on the structure have increased the flexibility with which capital enters the real estate market and created more tax-efficient structures for real estate ownership.

In 2005, approximately $3.5 trillion of capital was invested in the private nonresidential U.S real estate market, about 73 percent as debt and 27 percent as equity.1 Moreover:

Steiner + Associates partnered with Mall Properties, Inc., to provide a portion of the equity for construction of Zona Rosa in Kansas City, Missouri. Steiner + Associates is the developer and manager of the property. A consortium of five banks provided the construction loan; industrial revenue authority bonds also provided funds to support the project. At the time the construction loan was closed, 60 to 70 percent of the space was in some stage of leasing.

Although data from 2005 provide context, they reflect market conditions at only one time, conditions that change with overall conditions in the financial markets. In 2005, many investors, frustrated with low returns from stocks and bonds, came to real estate looking for higher and more reliable yields. Large amounts of capital flowed in, resulting in high liquidity for real estate and low cost of capital. Additionally, with an aging population, many private investors and pension funds sought income properties with reliable cash flows, thus raising prices for these properties and lowering the return necessary for them to attract capital.

The 2005 data also point to the sources where developers found capital. Equity sources included private investment firms and real estate advisers that manage investment pools, private individuals, REITs, and pension funds. Pension fund capital was usually placed with a real estate advisory firm for management.

In the last 15 years, the growth of commercial mortgage-backed securities has substantially increased the flow of capital into commercial real estate development. These loans, which are originated by loan brokers as well as some banks and life insurance companies, are sold to a loan pool, which is then securitized and sold as a rated investment. This source of capital has dramatically affected liquidity for real estate. “Nothing short of revolutionary, the CMBS impact on U.S. real estate markets has been mostly responsible for providing a strong consistent source of liquidity to property owners.”2

Finding sources of capital tailored to a developer’s style and a project’s character takes work—surveying available sources as well as developing a relationship with a few sources that make deals. Frequently, a new development entity enters into a joint venture with an experienced larger entity to learn the ropes and develop a track record. Sometimes lenders and investors back new entities on smaller projects. Development entities comprising individuals who come from development-related disciplines such as financing, law, construction, or architecture have a head start. A local ULI district council is a place to start meeting people from capital firms. Real estate attorneys frequently know of wealthy individuals who individually or as part of a pool are interested in real estate investment. New development entities need to work hard to establish a reputation for reliability with financing sources so they can build a long-term business relationship.

For new development projects, lenders and investors care as much about whom they are doing business with as they do about what they are financing; thus, a development entity’s financing package must speak to the reliability and credibility of the developer as much as it does to the merits of the project. With slight variations, the financing package for equity and loans addresses the same elements:

The lender will be interested in the project’s meeting specific underwriting criteria so that the loan can be sold to a pool that issues CMBSs. The investor evaluates the project in terms of meeting minimum yield requirements and providing upside opportunties.

Frequently, lenders and institutional investors have their own proprietary software and format for presenting a project, and the development entity must ensure accurate transfer of information into these new frameworks.

As part of the financing package, a development entity addresses the proposed merchandising mix. Bishops Square in London contains carefully selected tenants, creating an eclectic mix of shops and bars to deliberately reflect the ethnic diversity of the area.

A development entity usually, though not always, begins the discussion about financing with investors. Loans are frequently shopped through “loan brokers,” who look for the best rates. Getting a lower-cost loan without strong support by the lender on the inevitable things that go wrong on a project can be a poor deal, however, and the developer must ensure that the lender for the project has the capacity to participate in problem solving. The developer should not view any aspect of the financing as a commodity and should choose financial partners after careful consideration of the person or entity to determine who will do the best overall job for the project.

Lenders and investors have somewhat countervailing interests. The higher the loan, the greater the risk to the lender but the greater the potential return to the investor, because a higher loan results in a lower required equity investment. A lower loan means lower risk for the lender but a higher equity investment, resulting in a lower return to the investor. This countervailing interest should be resolved early in the development process, after which both funding parties have an interest in the project’s success. A developer needs the relationship between lenders and investors to be cooperative, especially when things such as construction delays, nonperformance by key tenants, or a natural catastrophe do not go according to plan.

Equity investors operate on the same principle that governs all successful transactions in real estate: invest with reliable and trustworthy people. Experience is the single most important determinant of the terms of investment.

Equity investors frequently require a developer to coinvest on a project. A typical requirement for coinvestment is 10 percent of the total equity. This requirement is frequently waived for developers with a strong record of performance. A developer that puts more into a project has more control over key project decisions and will be able to negotiate lower borrowing rates.

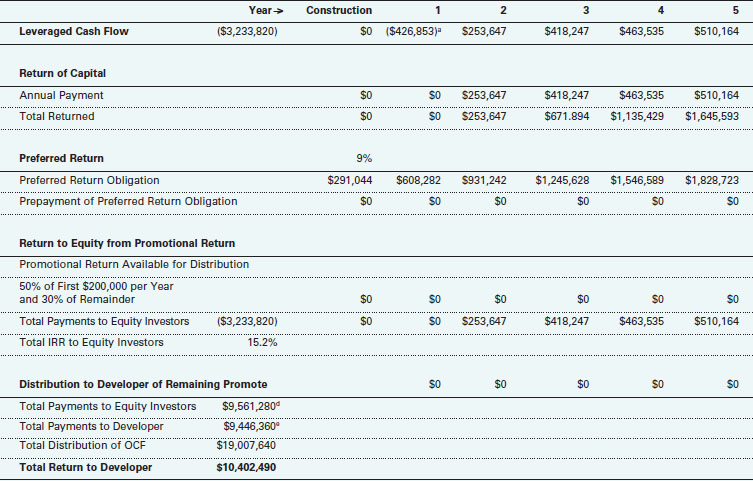

Equity investment is repaid from OCF and capital events, usually after meeting explicit provisions for debt repayment. The order of equity investment repayment is, first, return of principal; second, preferred return; and third, promotional return, which is divided on some negotiated formula between the equity investor and the developer. The promotional return (or “promote”) is the accrued obligation for distribution from OCF after return of principal and preferred return have been paid.

Preferred return is a rate applied to the principal equity balance outstanding that accrues as a first priority obligation of the project after repayment of debt and investment (or equity) principal. Currently, the preferred return varies from 8 to 12 percent, depending on what is negotiated between investor and developer. Beware a high preferred return, as it compounds on any equity balance outstanding; any delays in project opening or in reaching positive OCF will eat up profits that would otherwise be distributed between the developer and investor.

Promotional return distribution formulas vary widely and depend on the relationship between investor and developer. Some promotional returns are distributed pari passu (“of equal steps”) between investor and developer. Some are distributed in a “waterfall,” with the investor receiving a high percentage on a first tier of return and a lower percentage on the second tier.

Capital events (refinancings or sales) may have different distribution formulas that allow the developer a higher percentage share of the distribution to encourage positioning a project to capitalize on these opportunities.

Investment capital flows to a project under a joint venture or partnership agreement that stipulates the use of the funds, the roles of the parties, the business plan, and the decision-making process. See “Elements of a Joint Venture” below for a discussion of the generic issues to be addressed in a joint venture agreement.

The only thing one needs to borrow money is the ability to pay it back, or, to put it another way, lenders are not in the business of making loans that are not secured by both verified cash flow and assets. Unlike investors, lenders are not looking for an upside; they just want to make sure that the project will pay its bills and, if it does not, that the foreclosure has sufficient value to cover the loan balance.

A retail development project needs two types of loans: a construction loan and a permanent loan. Both types of loans ultimately rely on the project’s value for security. Both types of loans also usually require performance guarantees, making the developer responsible for construction completion, budget performance, and lease-up.

Performance guarantees are so-called recourse provisions. Nonrecourse loans have much lower LTC ratios and, consequently, higher equity requirements and lower leverage on return. These guarantees require that the developer provide, at a minimum, a completion guarantee on the project construction. Other guarantees could include budget performance or lease-up. To secure these guarantees, the lender has recourse to the developer’s assets and may even put a lien on assets as security for the pledge. The developer’s assets that are not included as security for the guarantee must be identified in a “carve-out agreement.”

It is not unusual in the highly liquid capital markets of the early 21st century for developers to wait until after construction starts to seek a permanent loan. Capital markets have been so liquid that the permanent loan can be negotiated nearer to when funds are actually available to the project and project costs are better known. Developers can also buy forward commitments for a funding amount and rate for a fee.

Dolce Vita Coimbra in Coimbra, Portugal, was made possible by international public funds for the so-called Eurostadium project, which was planned as a synergistic project containing residential, retail, office, entertainment, and sports facilities.

Construction lenders have several conditions to ensure that the project’s value is always sufficient to secure the loan. Investors need to put their money in first. They may require preleasing commitments to ensure that the conditions necessary for a permanent loan are met. As the project draws money from the loan to pay contractors, the lender ensures that the value of the project always exceeds the loan value outstanding. The lender also requires that mechanics’ liens (liens by subcontractors who have not been paid) are all released (or paid and cleared).

The best way to ensure a smooth relationship with a construction lender is through competent construction management. Documentation of what is completed and the management of relationships between contractors and subcontractors ensures smooth construction draws and timely funding. A streamlined process of resolving disputes is also usually a condition of the loan to ensure timely decisions.

The Lakes at Thousand Oaks in Thousand Oaks, California, sits on a site left vacant for about 20 years after Jungleland, home to many “actor animals,” closed. The city eventually purchased the land through eminent domain to stop a big-box retail development. Planning began in conjunction with a nonprofit organization to develop a discovery center, but funding for the center languished over three years; after several alternative master plans, the city agreed to move forward on only the commercial project and to set land aside for a future discovery center.

Without guarantees by the developer, permanent lenders for a retail project usually require a significant portion of the project be leased as a condition of funding. Doing so gives creditworthy tenants—the tenants that are strong financially and on whom the lender can base the creditworthiness of the project—significant leverage in negotiating rents and other concessions on the project such as location and parking ratios.

Lenders secure their loans with a first deed of trust (a lien) on the project’s value, giving them a right to foreclose on the project if the loan is not repaid. Sometimes a lender syndicates a loan and segments loan components into so-called “A” and “B” notes, where the A lender has a first deed and the B lender has a subordinate lien or second deed of trust. Additional segmentation beyond A and B lenders is also a possibility.

Lenders may also require the loan to meet underwriting criteria, allowing them to sell the loan to a CMBS pool.

Each real estate project can be viewed as its own business enterprise with its own stand-alone financing structure. If several development entities are involved in a project, they will probably form a new consolidated entity, a “joint venture,” to pursue a particular project. Sometimes a joint venture is formed between a landowner and a development entity to allow the landowner to participate in a project as a development partner. Almost always, a joint venture agreement is the vehicle that stipulates the terms under which investment equity flows to a project.

A joint venture is a contract between existing entities, but it can also be formed as its own partnership, or LLC. The contract addresses roles of the entities, requirements for contribution of capital, distribution of profits, and formation and dissolution.

Like most real estate contracts, the parties spend most of their time negotiating a joint venture agreement addressing the small number of the issues relating to what could go wrong. Although good contract provisions are critical to the success of a joint venture, the trustworthiness and reliability of the participants are the most important contributors to the success of the venture.

In a retail project, profits come from OCF and from capital events, i.e., refinancings or sales. Profits are distributed between outside equity investors and the development entity according to an agreed-upon distribution formula.

Some of the issues addressed in a joint venture agreement include:

1. Participants in the Joint Venture—In general, all the participants are separate business entities, but some may be individuals, such as a landowner. The joint venture could be structured as a partnership or an LLC. Note that a joint venture that is a general partnership requires that the partners form some entity of their own to protect themselves from personal liability.

2. Purpose of the Joint Venture—Among the possible purposes could be:

Acquisition, entitlement, development and sale, or ownership and management of property separately or collectively for a specific use or mixture of uses;

Acquisition, entitlement, development and sale, or ownership and management of property separately or collectively for a specific use or mixture of uses;

Creation of an entitlement on property with sale before development of all or a portion thereof.

Creation of an entitlement on property with sale before development of all or a portion thereof.

3. Project Description—What property or project is involved:

Description of the property(ies) and project(s);

Description of the property(ies) and project(s);

Current contracts, letters of intent, or purchase agreements;

Current contracts, letters of intent, or purchase agreements;

Current entitlements;

Current entitlements;

Expected activities of the joint venture to pursue the project(s).

Expected activities of the joint venture to pursue the project(s).

4. Information and Decision Making—Terms should reflect how the partners will share information, what the role of each party is, how final decisions are made, and who makes them.

Communication and information-sharing methods should be clearly described.

Communication and information-sharing methods should be clearly described.

Roles of each party to the joint venture should be defined.

Roles of each party to the joint venture should be defined.

How decisions are made should be defined.

How decisions are made should be defined.

Some key decisions may require concurrence from all members of the joint venture.

Some key decisions may require concurrence from all members of the joint venture.

Typically, one entity is involved primarily in different aspects of the deal. For instance, one entity may be primarily responsible for obtaining entitlements, another may work as public spokesperson, and another may have primary responsibility for securing loans and outside investors.

Typically, one entity is involved primarily in different aspects of the deal. For instance, one entity may be primarily responsible for obtaining entitlements, another may work as public spokesperson, and another may have primary responsibility for securing loans and outside investors.

5. Business Planning and Budgeting—The agreement should reflect the current business plan and budget as well as provisions for periodic updating. The issues to be addressed include:

The responsibility of each partner to contribute to capital. When the joint venture is among development entities, the contribution is developer capital, which includes all funds required for the organization and operation of the development project net of third-party financing by financial institutions or other investors.

The responsibility of each partner to contribute to capital. When the joint venture is among development entities, the contribution is developer capital, which includes all funds required for the organization and operation of the development project net of third-party financing by financial institutions or other investors.

The expected outside limits of the requirements for capital contributions and the mechanisms for addressing the circumstance when contributions reach the outside limits should be stipulated.

The expected outside limits of the requirements for capital contributions and the mechanisms for addressing the circumstance when contributions reach the outside limits should be stipulated.

If a member of the joint venture is the landowner, then the value, or some agreed-upon method of valuing the land, should be stipulated.

If a member of the joint venture is the landowner, then the value, or some agreed-upon method of valuing the land, should be stipulated.

The tasks to be accomplished and the role of each joint venture partner in accomplishing these tasks should be spelled out.

The tasks to be accomplished and the role of each joint venture partner in accomplishing these tasks should be spelled out.

6. Management Services for the Joint Venture—Sometimes one of the partners assumes responsibility for accounting, filing taxes, and so on, especially if the joint venture is not anticipated to be an LLC or some other recognized business entity immediately. Provisions should be made for anticipating a transfer of this function when necessary.

7. Sharing Profits—The contract must address how profits are distributed among participants (see “Distribution of Profits” below).

8. Sharing Fees—The lender and outside investors frequently permit the development entity to charge fees to the project reflecting services provided. The joint venture agreement needs to address how these fees are divided among the parties (see “Development Fees” below).

9. General Provisions—Terms of the agreement need to address generic issues, including confidentiality, taxes, disagreements, death, and bankruptcy.

Disputes leading to termination are typically addressed with a “buy-sell provision.” Be careful here. It is not something to view as a cure-all backstop, because it is problematic in its own right. A buy-sell provision generally provides that either party may propose a termination of the joint venture based on the offering party’s valuation of the joint venture and its assets and liabilities; the other party then has the right to elect to buy the other party’s interest or sell its own interest for a price based on that valuation.

Disputes leading to termination are typically addressed with a “buy-sell provision.” Be careful here. It is not something to view as a cure-all backstop, because it is problematic in its own right. A buy-sell provision generally provides that either party may propose a termination of the joint venture based on the offering party’s valuation of the joint venture and its assets and liabilities; the other party then has the right to elect to buy the other party’s interest or sell its own interest for a price based on that valuation.

Death of a key individual should also be addressed in a manner that allows the parties to the joint venture to continue the project by purchasing the deceased party’s share. Key-man life insurance is an option, though expensive. The process for valuing the share of the deceased party should probably involve a third party’s appraisal.

Death of a key individual should also be addressed in a manner that allows the parties to the joint venture to continue the project by purchasing the deceased party’s share. Key-man life insurance is an option, though expensive. The process for valuing the share of the deceased party should probably involve a third party’s appraisal.

Confidentiality and public announcements need to be addressed, particularly if one of the members of the joint venture is a publicly traded company and must meet disclosure requirements of the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Confidentiality and public announcements need to be addressed, particularly if one of the members of the joint venture is a publicly traded company and must meet disclosure requirements of the Securities and Exchange Commission.

The public/private partnership between the developer and the city of Aurora, Colorado, was a vital element in the development of Southlands. Master entitlements guided the uniform development of the project—architectural design guidelines, master sign criteria, landscaping, density, and use—which were heavily negotiated at the beginning. From the initial approval date, no further public hearings were required, as all approvals occurred administratively at the staff level, significantly reducing the time to market. In cooperation with the city, two metropolitan districts with a total capacity of $40 million were created. Private bonds used the taxing authority granted to the districts for public infrastructure.

A real estate development entity typically allocates profit between investment dollars and “talent.” Depending on the project’s profitability and the requirement for return on investment, 30 to 70 percent of the project’s profit is distributed to the investment side of the partnership and the remainder to talent. This distribution is particularly relevant in partnerships or joint ventures where different parties have different roles. Some may be limited partners who are simply investors. Others may have all the development skill and invest little money, contributing primarily talent. Negotiating the split of profits between investment return and talent return is a major effort associated with the funding of any development project.

Once agreement has been reached on the percentage of profits that will go to repay investment, allocations from this flow are typically distributed proportionate to the amount of investment made by each partner. For example, an investor putting up 20 percent of the investment would receive 20 percent of the profits distributed to the investment side. It is not unusual to include a “penalty dilution” of the distribution of profits to the investment side to ensure that investors meet their obligations. For example, if the agreement is that each partner contributes half of a $4 million budget, and one partner is short by $400,000, that partner’s share of the distribution of profit drops to less than the 40 percent of the budget the partner ultimately contributed, even though his contribution of $1.6 million represented 40 percent of total equity. Further, a possible penalty dilution provision could say that a partner’s failure to meet his obligations for a contribution would cause the distribution percentage to fall 1.5 percent for each 1 percent of shortfall.

Allocations to the talent side vary considerably, depending on the mix of partners and the nature of the project. In general, the talent side is allocated according to how the parties negotiate the distribution, which depends on such factors as the role of each party, which party controls the development opportunity, which party is “bankable” and can provide assets for recourse loans, and which partner has skills vital to the success of the project.

Liabilities of the development entity involve both predictable and unpredictable costs. The development entity frequently must finance all the predevelopment costs before outside investors and lenders will fund construction of the project. These predevelopment dollars carry a high risk and warrant the development entity’s receiving a significant return (see “Funding Predevelopment Costs”).

In addition, it is not unusual for outside investors to require that a development entity invest as much as 10 percent of the equity requirement as a coinvestment in the project. A developer’s advances to cover predevelopment costs are counted toward this coinvestment obligation. Thus for Hypothetical Project, with an equity requirement of $3,233,820, the developer needs to coinvest $323,380, reducing the outside investor’s requirement by that amount. If the developer spends more than the required coinvestment during predevelopment, that overage could be returned at project funding.

All these costs are predictable and should be budgeted by the development entity at the start of the project. If budgeted costs are exceeded, the development entity frequently is responsible for meeting the funding shortfall. Provisions for addressing how this additional developer capital will receive a return must also be negotiated. It is the need to deal with unpredictable costs that test the strength and ingenuity of the development entity.

Predevelopment costs are costs incurred for the project before the start of construction and its funding by lenders and outside investors. These costs are the most at-risk expenditures a developer makes on a project because they are incurred before the project is approved for development by the city or county and before the lender and outside investors fund actual project construction. They include entitlement processing (design, special studies, community outreach, and so forth), nonrefundable land deposits, and preconstruction management. Even for a moderately sized project in today’s regulatory environment, they can easily reach $500,000 to $1 million.

In general, it is desirable for the development entity to fund these costs from its own resources and not to bring in outside investors. Unless the developer already owns the property, loans are difficult to obtain. Until the project is entitled, the risk of its not proceeding may be high, with outside investors consequently demanding a high return. At the same time, it is critical that the development entity carefully manage predevelopment liabilities, for this period is the one during which the development entity faces the highest risk of loss.

Investors and lenders frequently authorize the developer to take “fee income” associated with services provided to the project. This source of income to the development entity provides needed cash flow and can provide appropriate income to the development entity before the developer’s receipt of distributions from cash flow, which typically occurs after investors receive their preferred return. Practices vary considerably among project types and investors. Typical generic fee income is a “developer fee,” which is charged when the project is successfully financed and is usually paid along with the construction draw. Other fees include those for acquisition, marketing, and construction management (this list does not include all types of fees). These fees pay the developer for time spent on the project. Frequently they pay the developer for services that would otherwise be provided by third-party professionals. As costs, they reduce the profits available for distribution. How the development entity shares fees among its joint venture participants is based on considerations of role and value added.

In the 1990s as part of the savings and loan shakeout, lenders tightened underwriting criteria and developers began looking for assistance from public agencies for help in financing the public improvement components of private development projects. Many public agencies responded by using tax-exempt bonds for those parts of private development projects that could legally qualify for public financing. This trend became pronounced for large land development projects, but many of the same tools were applied to retail projects, especially in states where local governments participate in sales tax and an incentive exists for local governments to assist retail projects.

Two types of public debt are commonly employed to assist private development projects: land-secured bonds and tax increment financing (also called tax allocation or redevelopment financing). Both types of debt carry a tax-exempt interest rate that is typically 200 to 300 basis points lower than conventional financing. Public sector bonds also have typically longer amortization periods (frequently 30 years) than private loans.

Such bonds are useful for financing public improvements that are required for the project and would otherwise have to be privately financed to cover their costs. For retail projects, a major area of opportunity is publicly financed parking, but other improvements could include intersection improvements, street widening, streetscape improvements, and sewer or water lines. These bonds are also useful for installing public improvements in larger areas where a retail project may be one of many uses in a larger master plan.

What makes a mixed-use project more complex than a single-use development? Part of the answer lies in the assessment of how well the two or more uses work synergistically as a single development, but it also comes from the fact that components of income are from more varied uses than, for example, a 40-story office building with ground-floor retail, where the vast majority of revenue is derived from the office portion.

It does not matter how great a development deal is. If capital providers are not comfortable with the developer’s ability to complete the job on time and on budget or deal with cost overruns, the development may not be financeable. If unleveraged yield of overall economics is too tight, the developer’s track record does not matter: the money will not be there for mixed-use or single-use developments.

The following three recently financed mixed-use projects by Ackman-Ziff show how the difference in project size does not necessarily affect how a mixed-use project is successfully financed.

CityPlace. CityPlace is a 72-acre (29-hectare), $600 million, 2.8 million-square-foot (260,000-square-meter) mixed-use development in West Palm Beach, Florida. Completed in October 2000, Phase I consists of a 620,000-square-foot (57,600-square-meter) open-air entertainment-enhanced retail center with 586 apartments, condominiums, and lofts above ground-level retail space. Overall, the project combines specialty retail stores, private residences, and a hotel and convention center into one architecturally distinctive mixed-use development.

The first phase cost approximately $314 million, which was capitalized through three equity sources— an institutional joint venture, retailer equity, and developer equity—construction financing, and a TIF package. TIF was used to finance infrastructure, which included structured parking, sidewalks, a plaza, fountains, landscaping, and other public areas.