Under standard definitions of shopping centers, Los Jardines, at 78,000 square feet (7,250 square meters) with a 30,000-square-foot (2,790-square-meter) anchor tenant, would be classified as a neighborhood center. But this newest invention of Beverly Hills-based Primestor Development is proving to be the exception. Despite its relatively modest size and its location, Los Jardines in many ways functions more like a community center in the sense that it has become a focal point for community life in Bell Gardens or even a regional center in that it routinely draws patrons from well beyond the immediate community. This larger-than-typical trade area (for a center of its size) is attributable to at least four factors: 1) the developer’s commitment to create a sense of place through the architectural and physical configuration, the tenant mix, which combines national retail chains with local and regional businesses, and an extensive community outreach program; 2) an anchor tenant (Famsa, a Mexico-based electronics and home furnishings chain) with tremendous name recognition in the Latino community (the trade area’s population is 87 percent Hispanic); 3) immediate proximity to other retail development and to a major casino, effectively creating a critical mass comparable to that of a large community shopping center; and 4) location in a densely populated trade area (more than 900,000 people within a five-mile (8-kilometer) radius that for years has been severely underserved with high-quality retail development.

The project is located on a seven-acre (2.8-hectare) site in an urban, blue-collar, largely Hispanic neighborhood. The city of Bell Gardens, about six miles (10 kilometers) southeast of downtown Los Angeles, encompasses 2.4 square miles (6 square kilometers) and has a resident population of about 46,000.

The site was assembled from 19 separate parcels that previously contained apartment buildings, abandoned commercial buildings, an operating but outdated Taco Bell restaurant, an adult bookstore, vacant land, and a public alley. The city, operating as the Bell Gardens Redevelopment Agency, assembled the land and relocated the tenants. The Taco Bell franchisee was recruited to be a tenant of Los Jardines and has no regrets about the change: the Taco Bell Corporation has praised the new building for the architectural detail, and it is now one of the most successful restaurants in the chain.

The site is at the intersection of Florence and Eastern avenues, which the developer describes as “Main and Main.” At the northeast corner are Los Jardines and an older 70,000-square-foot (6,505-square-meter) shopping center; at the northwest corner a 160,000-square-foot (14,900-square-meter) neighborhood shopping center anchored by a supermarket and a pharmacy; at the southwest corner one of California’s largest card casinos and a major southern California entertainment destination; and at the southeast corner another seven-acre (2.8-hectare) vacant site owned by the Bell Gardens Redevelopment Agency. The agency recently selected Primestor to develop this site as well, based largely on Primestor’s success with Los Jardines. The site’s tenants will include a Ross Dress For Less, a Marshalls, and a nationally recognized sit-down restaurant. Whereas Florence and Eastern are both major commercial corridors, the other two sides of the Los Jardines site are bordered by older residential development, mostly smaller single-family units.

As part of Primestor’s community outreach during preconstruction, local children painted ceramic tiles that were then incorporated into the streetscape.

The older shopping center on the northeast corner adjacent to Los Jardines is owned and anchored by Toys “R” Us. Although owned and operated separately (and currently much less attractive than Los Jardines), this neighboring center effectively functions as part of Los Jardines; were it not for the stark contrast in architectural quality, a shopper would never know that the two centers are separate entities. Primestor characterizes Toys “R” Us as a “shadow anchor” for its project. The relationship between the two centers is formalized in a reciprocal easement agreement, which enables Los Jardines to share the other center’s “surplus” parking and, in return, enables the prominent listing of Toys “R” Us on Los Jardines’s two marquee signs (one of which is actually located on the other center’s property). In the absence of the agreement, it would have been necessary to physically separate the two centers, which clearly would have defeated the goal of creating synergy between the two. Moreover, the shared parking arrangement brought Los Jardines’s parking ratio in line with the expectations of the retail tenant community (Los Jardines’s own parking amounts to 3.9 spaces per 1,000 square feet [93 square meters] of GLA, just shy of the “four per 1,000” requirement of major national retail tenants; with the other center included, the ratio is 4.26 spaces per 1,000 square feet). Plans are now afoot to substantially renovate the Toys “R” Us center, consistent with the high architectural standards set by Los Jardines. To facilitate the process, the Primestor management team is donating its time to coordinate the neighboring center’s site improvements, and the redevelopment agency is paying the architectural fees.

The story of Los Jardines is really the story of Primestor Development, its development philosophy, and its successful partnership with the Bell Gardens Redevelopment Agency. Primestor was started more than 20 years ago, initially focusing on property management. The firm’s principals, Arturo Sneider and Leandro Tyberg, are both immigrants from Latin America (Sneider from Mexico and Tyberg from Argentina). Through their experience in property management, Sneider and Tyberg were keenly aware of the tremendous gap in retail goods and services in Latino communities and, in 1997, decided to do something about it. They shifted Primestor’s focus from property management to development and decided to concentrate strictly on urban infill projects. At that point they brought Gene Detchemendy on board as a partner, based on his strong background in directing real estate projects for urban-oriented tenants.

Los Jardines has a long-term ground lease with the Bell Gardens Redevelopment Agency, structured to allow for economic feasibility while still providing an income stream to the agency. The ground lease facilitated a project that otherwise would have faced large land assembly and relocation costs.

Los Jardines is Primestor’s tenth shopping center (all are in Latino communities in the greater Los Angeles area). The firm’s successful formula includes considerable attention to architectural details and site amenities, an ability to attract top-drawer tenants to neighborhoods that they have historically avoided, an understanding of the importance of public/private partnerships for urban redevelopment projects, and full engagement of a project’s residential and business neighbors during planning.

Primestor’s hands-on approach to community outreach is perhaps the feature that most sets it apart from its competition. Tyberg, who spends a large portion of his time on outreach, is emphatic about the need to build an ongoing relationship with local stakeholders: “In these areas, a project simply won’t happen unless it has community support,” he says. This message resonated with the city of Bell Gardens. The city’s redevelopment agency selected Primestor after three previous project proposals for the site (over ten years) had failed to come to fruition. Primestor’s competitors for the site included firms that were much larger and better known but lacked grassroots experience in Hispanic neighborhoods.

Overall development, from Primestor’s selection by the agency through the project’s grand opening, took three years. Primestor began marketing the project immediately upon being selected by the agency. Primestor and the agency took approximately six months to negotiate the terms and development agreement. Essentially, the deal involves a long-term ground lease, structured to allow for the project’s economic feasibility while still providing an income stream for the agency. The ground lease arrangement is consistent with Primestor’s intent of creating a long-term partnership in which the developer and the community both have a vested interest in the project’s success.

The entitlement process took about four months and was largely a formality because of the strong city/ community support that already existed for the project. Primestor needed to obtain a conditional use permit because the project would include a drive-through restaurant and to get tentative tract approval to consolidate the original 19 parcels making up the site. Both the planning commission and the city council voted unanimously to approve the project.

Site planning and design took approximately six months, construction about eight months. The community was involved throughout the process, from town hall-type meetings to job fairs to encourage the hiring of locals (more than 11,000 applications were received and distributed to all the center’s tenants) to inspections during construction to a grand opening fiesta. During preconstruction, local children were invited to come to a neighborhood youth center to paint customized ceramic tiles that ultimately became part of the streetscape. Involving the center’s younger neighbors not only served to build a customer support base among their parents but also affected the community’s sense of ownership of the project. According to Tyberg, “The children who worked on those tiles still bring their families to the center to see the work they did. It is a common sight to see a seven- or eight-year-old at the center with a parent, looking for the tile he painted.”

The project is on city-owned land. The ground lease with the city is for 55 years plus 30 years of options. Ground lease payments are $65,000 per year. Development costs (including $100,000 in capitalized ground lease payments) totaled $12.2 million. Primestor used a conventional construction loan of $9.75 million from KeyBank, which was repaid with the company’s own equity at the completion of the project (there is currently no mortgage on the property). According to Tyberg, “It was our commitment to this project to put in our own equity, in part as a measure of how much we believe in what we are doing.”

As part of its ongoing marketing program, Primestor imported fresh snow, a new experience for many of the children.

The walkway is part of the overall objective of creating a community gathering place as well as a place to shop.

Architecture is an integral part of the value that Primestor creates for its tenants and neighborhoods. The common threads running through all the firm’s projects are highly attractive architecture and landscaping, a pedestrian orientation, and public amenities that express the heart of the community. The firm strives to design its shopping centers from a neighbor’s instead of a customer’s perspective, creating places where people come to spend time even if they do not always spend money. According to Tyberg, “Hispanic buyers are very loyal. Even if they don’t spend money on every visit to the center, they will return if the experience is positive.”

Creating a community gathering place was the main objective of the architectural firm Perkowitz + Ruth retained to design Los Jardines (and now working for the redevelopment agency on the renovation of the adjacent center). To that end, the site incorporates a community fountain/plaza area, thematic landscaping (northern Mexico/Sonora Desert), and a botanical walkway. Key species in the landscaping palette include palm trees, non-fruit-bearing olive trees, agave, dragon trees, and ocotillo.

The building architecture is inspired by traditional northern Mexican design—light colored, hand-troweled smooth stucco walls accented by darker colors on the roof tiles, stone columns, and ornamental iron light fixtures. Five hundred azulejos—the traditional ceramic tiles painted by neighborhood children—provide a personal touch to the center’s architecture. Portions of the main building have faux second floors, with bougainvillea plants hanging from the balconies. Other features include trellises and an overhanging canopy archway where music is always playing. The project has two 38-foot (11.5-meter) pylon signs with ledger stone bases that match the overall building style. Based on tenants’ expectations, the fascia signage is conventional and probably the one concession to the homogeneity of American retailing.

Each storefront is recognizable as a separate business, achieved by using different accent treatments throughout the project and varying building depths. The number of outparcels was intentionally limited, and they were carefully placed so as not to block visibility of the main building from Eastern Avenue, the site’s main commercial frontage. Parking is ample.

Unlike other Los Angeles-area projects in urban settings, Primestor’s centers are never fenced. In the firm’s experience, the downside of limiting community access (and thereby undermining the primary goal of creating an inviting environment) far outweighs the perceived security benefits of fencing. Indeed, Primestor maintains that its shopping centers are much less frequently targeted by graffiti and other vandalism than other properties in their neighborhoods. The firm’s principals attribute this fact to the tremendous effort they make to build goodwill before they build buildings.

The Los Jardines tenant list includes Starbucks, Red Brick Pizza, Panda Express, Quiznos, Cingular Wireless, Bank of the West, Cold Stone Creamery, and Hollywood Video—the names usually found in newer retail centers in affluent suburbs. This seeming anomaly is perhaps what is most noteworthy about Los Jardines and Primestor’s other projects. Primestor’s principals credit their success at recruiting tenants to their track record and their resulting personal relationships with tenants. Whereas five or ten years earlier it would have been virtually unheard of to attract such tenants to Bell Gardens, with each project Primestor has gained momentum in breaking down the barriers to urban retail development. And the success of Los Jardines has further enhanced the firm’s credibility among major retail chains. Ross Dress For Less and Marshalls, which Primestor recently signed for its new project across the street, both passed on Los Jardines when it was first marketed.

The other interesting aspect of the Los Jardines tenant mix is that it combines U.S.-based national chains with regional tenants and includes Famsa, a major retailer in Mexico (more than 200 stores) with an emerging presence in the United States (about ten in southern California and Texas). Overall, 70 percent of the center’s GLA is occupied by national chains, with the other 30 percent occupied by smaller regional chains based in the Los Angeles area. Famsa, the center’s 30,000-square-foot (2,790-square-meter) anchor tenant sells furniture, appliances, and electronics. Its U.S. stores have a hybrid merchandise mix, combining Famsa’s own products with major brand names. Famsa products are familiar and popular among recent immigrants from Mexico, whereas name brands tend to appeal more to American Latinos. One of the keys to Famsa’s initial success in this country is that its stores offer a convenient service that enables customers to purchase products at its U.S. locations and have them delivered to family and friends south of the border directly from its Mexican stores.

Primestor’s focus on creating community gathering places and its emphasis on public outreach are the foundations of its marketing efforts. Although the firm clearly recognizes the crucial role of outreach in gaining the community’s support before a project breaks ground, it also firmly believes that outreach needs to continue as a permanent part of a shopping center’s operations. Primestor’s ongoing marketing program includes free concerts and events throughout the year, some planned in partnership with a tenant, Latin Music Warehouse; holiday cards mailed to all residential and business addresses in the center’s zip code; holiday-themed events (during the 2004 holiday season, for example, Primestor imported fresh snow and placed it on a large section of the parking lot, attracting children—most of whom had never actually seen snow— from miles around); and support and sponsorship of events held by the local chamber of commerce.

True to its belief that successful urban development requires a long-term partnership between the developer and the community, Primestor serves as the ongoing management team for all the shopping centers it builds. As a way of conveying the message that the firm is committed to its projects for the long haul, Primestor prominently posts its phone numbers at its shopping centers and encourages patrons to call with any concerns.

Primestor is not a big believer in market feasibility studies, and for Los Jardines, the firm did not complete any type of formal market analysis. Tyberg describes their approach to evaluating development opportunities as more intuitive: “This is our community and we know what it needs. When we drive down the street and see that people have no place to shop or to dine, we know there are opportunities.” The firm’s performance record vindicates this approach: its ten shopping centers are all financially successful and have an average occupancy rate of 98 percent. Los Jardines is 100 percent leased.

Since the release of the 2000 Census data, developers and retailers have begun to wake up to the tremendous possibilities of the Hispanic market. In places like southern California, the market is too obvious to be ignored, but the trend is also significant nationally. Projections released by the Census Bureau in early 2004 indicate that the nation’s Hispanic and Asian populations will triple over the next 50 years and that minorities will represent fully one-half of the total U.S. population. Thus, projects like Los Jardines are not only useful models for urban redevelopment but also important guideposts for tapping the burgeoning spending power of American Latinos. Primestor, which so far has developed projects only in southern California, is poised to ride the wave of its success into the national marketplace. The firm is actively looking for infill development opportunities throughout the country.

Thanks to pacesetters like Primestor and milestone projects like Los Jardines, the tenant and equity communities are becoming more receptive to urban infill projects. Given the weight of anticipated demographic trends, it is probably not an exaggeration to characterize Latino communities as one of the next major frontiers for shopping center developers.

Nevertheless, the Primestor team is careful to distinguish between developing projects in Latino communities and pursuing Latino-oriented development. Certainly, knowledge of a community’s cultural background is helpful in understanding its residents’ shopping preferences. But in the final analysis, shoppers in these communities are looking for essentially the same thing as suburban shoppers: a high-quality shopping experience defined by the attractiveness of the physical setting and by the mix of tenants. Los Jardines, by virtue of its architecture and its very mainstream tenant roster, is proof that a high-quality shopping center in an urban area is not too different from a high-quality shopping center anywhere.

Successful development or redevelopment in an urban setting is all about leveraging relationships: with the city, with the community, and with tenants and equity partners. Close collaboration (if not a formal partnership) with the public sector is typically an essential ingredient. In this regard, the developer needs to view the city as a partner instead of an obstacle. In turn, city leaders need to appreciate the value the developer is creating and the risks it is assuming to do so. Although some developers shy away from public/private partnerships because of the prevailing wage mandates involved, Primestor sees them as another opportunity to build goodwill in the community.

For developers who understand the demands of urban infill projects, the financial and intangible rewards can be great. At the end of the day, Primestor’s principals like to think that their work is really more about community building than bricks and mortar. Tyberg sums it up: “When a child walks to school and has to pass blighted, drug-infested buildings, it affects how he thinks about his community and about himself. Self-respect is a big part of what we’re trying to achieve. To see the improvement in these neighborhoods is breathtaking and utterly heartwarming.”

Los Jardines shares its corner of a major intersection with another center owned and anchored by Toys “R” Us, which functions as a shadow anchor for Los Jardines. The two centers have a reciprocal easement agreement that allows Los Jardines customers to use the other center’s parking lot. In return, Toys “R” Us is prominently listed on Los Jardines’s two marquee signs, one of which is located on the other center’s property.

| Land Use and Building Information | |

| Site area | 6.65 acres (2.7 hectares) |

| Gross Building Area | 77,952 square feet (7,245 square meters) |

| Gross Leasable Area | 197,466 square feet (18,350 square meters) |

| Floor/area Ratio | 0.27 |

| Number of levels | 1 |

| Total surface parking spaces | 305 |

| Land Use Plan | ||

| Acres/Hectares | Percent of Site | |

| Buildings | 1.77/0.72 | 27 |

| Surface parking/roads | 4.76/1.93 | 72 |

| Landscaped areas | 0.12/0.05 | 1 |

| Total | 6.65/2.69 | 100 |

| Major Tenants | |

| Square Feet (Square Meters) | |

| Famsa | 30,000 (2,790) |

| Hollywood Video | 6,133 (570) |

| Average Length of Lease | 5-10 years |

| Typical Lease Provisions | Taxes, insurance, CAM, utilities reimbursed |

| Annual Rents | $22-36 per square foot ($237-387 per square meter) |

| Average Annual Sales | $200 per square foot ($2,152 per square meter) |

| Development Cost Information | |

| Site Acquisition Cost | $100,0001 |

| Site Improvement Cost2 | |

| Excavation/grading | $360,000 |

| Paving/curbs/sidewalks | 413,000 |

| Landscaping/irrigation | 300,000 |

| Fees/general conditions | 50,000 |

| Other | 441,000 |

| Total | $1,564,000 |

| Construction Costs | |

| Superstructure3 | $7,647,000 |

| Tenant improvements | 814,000 |

| Total | $8,461,000 |

| Soft Costs | |

| Architecture/engineering | $446,000 |

| Project management | 60,000 |

| Marketing | 50,000 |

| Legal/accounting | 110,000 |

| Taxes/insurance | 85,000 |

| Title fees | 18,000 |

| Construction interest and fees | 549,000 |

| Other | 787,000 |

| Total | $2,105,000 |

| Total Development Cost | $12,230,000 |

| Annual Operating Expenses (2005) | |

| Taxes | $234,050 |

| Insurance | 63,366 |

| Services | 38,500 |

| Maintenance | 94,943 |

| Janitorial | 20,760 |

| Utilities | 32,100 |

| Legal | 4,000 |

| Security | 55,528 |

| Management | 85,105 |

| Miscellaneous4 | 74,160 |

| Total | $702,512 |

| Financing Information | |

| Source | Amount |

| Construction Loan, KeyBank | $9,750,0005 |

| Equity | 2,480,000 |

| Total | $12,230,000 |

Primestor Development

228 South Beverly Drive

Beverly Hills, California 90212

Architect/Planner

Perkowitz + Ruth

111 West Ocean Boulevard/21st Floor

Long Beach, California 90802

Other Key Team Member

CAMCO Pacific—Contractor

| Development Schedule | |

| 4/2001 | Site purchased by redevelopment agency; Primestor selected to develop project; leasing started |

| 10/2001 | Ground lease negotiated |

| 10/2001 | Planning started |

| 10/2002 | Approvals obtained |

| 8/2003 | Construction started |

| 4/2004 | Project opened |

Notes

1 Ground lease is $65,000 per year; approximately $100,000 was capitalized during the construction period.

2 On and off site.

3 Includes all trades.

4 Includes ground rent of $65,000 per year.

5 Construction loan paid off at the end of construction and not rolled into a permanent loan (i.e., there is no mortgage on the project).

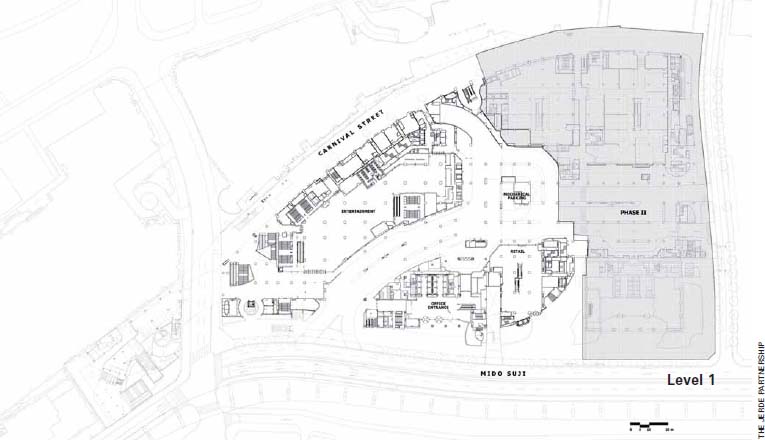

Namba Parks is an eight-story urban shopping center topped by an outdoor amphitheater and cascading rooftop green terraces that invite visitors to forget they are in the middle of the city. Most recently occupied by a vacated baseball stadium and off-track betting parlors, this 8.33-acre (3.37-hectare) parcel is in Minami, Osaka’s central business district. The site is part of a narrow strip of land owned by Nankai Electric, which has been progressively developing it over the course of half a century, starting from the densest end on the north. Surrounded by raised railroad tracks to the east and an urban boulevard and elevated viaduct to the west, Namba Parks provides 108 shops and restaurants arranged to form an indoor-outdoor retail and entertainment complex. A 30-story office tower, also incorporated into this site, is a visual anchor for the project.

Osaka is Japan’s second-largest metropolitan area (Tokyo and Yokohama can be considered one continuous metropolitan area). As Japan’s “Second City”—the comparison with U.S. cities and their reputations is apt, with Kyoto being Japan’s Boston and Tokyo being both New York and Los Angeles—Osaka, like Chicago, prides itself on its commercialism and industry, its aggressiveness and rowdiness. Osakans, in fact, traditionally greet each other with the phrase mokarimakka, or “Are you making money?”

Namba Parks extends the southern end of Minami. Minami’s main street is the 2.7-mile (4.4-kilometer) Midosuji (meaning “Great Hall Avenue” and named after a large Buddhist temple that once marked the street), a tree-lined boulevard that is compared with Fifth Avenue or the Champs-Elysées because of its grand proportions and the number of deluxe stores and high-fashion boutiques along its length. At its southern end, Midosuji extends to the Namba rail and subway station. Atop the subway station, starting at street level, is a seven-story branch of the famed Takashimaya department store. Nearby to the north is the 1,968-foot (600-meter) Shinsaibashi arcade mall, with 180 shops targeted to a youthful population. Across Midosuji from Shinsaibashi are more arcade and underground malls, all connected to Namba station and four other railway and subway terminals. Namba Parks sits immediately adjacent to the station to the south.

Namba Parks was jointly developed by Nankai Electric Railway and Takashimaya, a prominent department store chain based in Kyoto, with 24 stores in seven countries, including Japan, China, Singapore, and the United States. Nankai’s development subsidiary was formed in 1991 to maximize the value of the company’s extensive landholdings centered in Osaka. Founded in 1885, Nankai was named after the Nankaido, the ancient seacoast road extending from Nara to the southern end of Japan. The company owns and operates 105 miles (169 kilometers) of rail tracks in the Osaka region and is Japan’s 16th-largest railway company, ranked by its revenue from operations.

Like all Japanese railroad companies—and indeed like all large Japanese corporations with landholdings— Nankai has a long history in, and extensive experience with, real estate development. (In Japan, the sale of corporate real estate assets is stigmatized as a sign of upheaval and desperation for a company. Companies with real estate assets are, by default, also real estate developers.) Subways and railways—and their transit stations—historically have been privately owned. Japan Rail (JR), government owned until privatized and split into seven “baby” JRs in 1987, is an exception.

To comply with Japan’s sun-shadow law, the 30-story Namba Parks office tower was sited to cast its shadow most of the day on the adjacent thoroughfare. To the left (east) are the raised railroad tracks of Nankai’s Main Line to Wakayama, to the right (west), the grade-level Midosuji, a prominent boulevard in Osaka’s central business district, and the elevated Osaka-Kobe Expressway.

Namba station is Nankai’s flagship station. Its main line connects Osaka to Wakayama to the south, with an important spur branching off to Kansai International Airport, Osaka’s major international airport. Nankai’s monopoly on train travel between Osaka and its airport—21.7 miles (35 kilometers) away—brings thousands of travelers to Namba station, where they can transfer to Nankai’s or other subways. In 1957, Nankai and Takashimaya jointly developed a seven-story building atop Namba station to house the latter company’s 742,540-square-foot (69,010-square-meter) store and Namba City, a 300-shop indoor mall. Adjacent to the block, and connected to it, Nankai built the 36-floor, 548-room Nankai South Tower Hotel in 1997. In 2003, the Swissôtel chain was invited to assume its management under a 20-year lease.

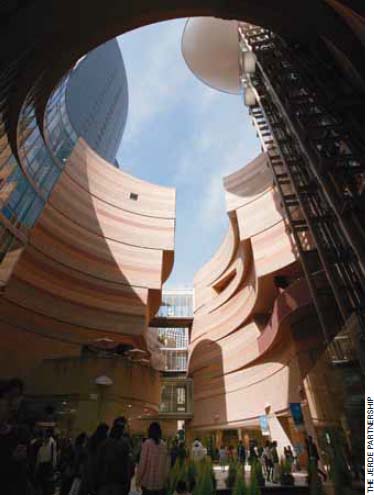

Serving as the main entry for patrons, the mouth of Namba Parks’s “canyon” at the left (north) leads to the oval-shaped center at the right (south). Nautilus-shaped motifs pay homage to the discovery of seashells, deposited back when the Namba district was part of Osaka Bay. At the top (east) are Nankai’s elevated railroad tracks.

The next steps in Nankai’s development of its Namba station properties were the construction of a three-level parking structure to serve the hotel, shopping patrons at Namba City, and Nankai’s own office building, and the second phase of Namba City, which added 300 shops under Nankai’s elevated railroad tracks out of Namba station and are open to the street.

Even the recently privatized baby JRs—unaccustomed to having to maximize shareholder value—now follow this model at their new stations. At Shin-Osaka station, which JR built as a terminal for its high-speed Shinkansen lines (one of which is the world-famous “bullet” train), JR erected a Granvia hotel and an entire city within a city of shops and restaurants. So has every other railroad, from the largest, JR East, to Nankai, ranked 16th.

In 1997, with Japan and Osaka still in the midst of a decade-long recession, Nankai began work on a new vision it had for the remaining 24.7 acres (10 hectares) of the Namba parcel. Nankai received encouragement from the Organization for Promoting Urban Development, a quasi-public agency, which had the ability to sponsor a loan guarantee from the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport for up to half the development budget for bond issues and private sector loans.

On this underdeveloped portion of Nankai real estate was the 21,000-seat Osaka Stadium, home of the major league Nankai Hawks until 1989. (In 1988, Nankai sold the Hawks to Daiei, a supermarket chain, which moved the team to Fukuoka.) It had been vacant since the team’s sale, its infield used as a parking lot. Under the ballpark’s outfield concourse were the off-track betting parlors of the Japan Racing Association, which had an inviolable long-term lease that required Nankai to construct a new 236,806-square-foot (22,010-square-meter) facility before the stadium could be demolished to make room for new construction. Nankai built it on two levels underground and developed Namba Parks around and over it.

Nankai and Takashimaya have been development partners since 1957, when Nankai contributed the desirable location above Namba station and Takashimaya contributed equity to establish a retail center at Osaka’s busiest commercial intersection. This form of long-term joint venturing is common in Japan, where the famed keiretsu (“brotherhood”) model of business partnerships has been both a blessing (capital formation is simplified) and a curse (it lacks a mechanism for introducing innovations) for the national economy. Indeed, business partnerships of equals are an absolute necessity in initiating large-scale projects.

At the pedestrian level, near Namba Parks’s oval-shaped center, a glass elevator shaft rises to an inverted hemispherical roof that serves as a projection screen for nighttime light shows and advertisements.

Although Nankai and Takashimaya are not engaged as a keiretsu (keiretsus, by definition, involve a merchant-banking relationship), the principles that promote keiretsus apply to the Nankai-Takashimaya partnership. The two have complementary strategies for managing the cyclical nature of their core businesses by strengthening the ancillary businesses that support the central operation. For Nankai, one such ancillary business is the maximization of value of its real estate assets. For Takashimaya, creating and supporting a critical mass of shoppers is vital to its industry-leading position as a chain of anchor department stores. The two have access to capital through their separate banking relationships, and with this source of debt financing, guaranteed by their parent companies and by the national Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport, the capital to undertake a development like Namba Parks is routinely granted.

Nankai has had a longstanding relationship with the giant Japanese general contracting firm Obayashi, which in turn had previously worked with the Jerde Partnership, a U.S.-based architecture firm. Having made its mark with Horton Plaza in San Diego, Jerde had expanded its practice in the design of retail environments in Japan and China. With each of its Japanese projects, the firm had experimented with different design concepts: at Canal City in Fukuoka, which opened in 1996, the conceptual premise was a canal extension of the underused Naka River; at La Cittadella in Kawasaki, it was a Tuscan hill-climbing circulation system for a site that had an existing Italian-themed nightclub; and at Roppongi Hills in Tokyo, it was an organic circulation system for the development’s 28.7-acre (11.6-hectare) site.

The oval center of the project opens to the sky. The curved facade of Namba Parks’s office tower and the landmark elevator tower’s finial face complement each other. The canyon is bridged by pedestrian walkways enclosed in glass, connecting the two eight-level retail wings.

Glass bridges reveal Namba Parks’s eight retail levels, giving patrons glimpses of shopping activity throughout the complex.

At Namba Parks, the conceptual premise is that of a canyon coursing through an urban park. A terraced complex of retail spaces envelopes an open space in the center, starting out as an oval vertical space, open to the sky and flowing out to the entrance. Near the entrance, up a ramp from street level, replicas of a home plate and pitcher’s rubber are set in the paving to mark the exact location of the demolished Osaka Stadium. During excavations, deposits of prehistoric seashells were discovered in the soil beneath Namba Parks, the location of which was once Osaka Bay, now 2.5 miles (4 kilometers) to the west. The use of replica seashells as a motif throughout Namba Parks lends further meaning to the theme of a canyon cutting across the layers of time.

The open space is irregular, curvilinear, and nonplanar in all dimensions. An elevator tower rises in the oval center, and glass-enclosed pedestrian bridges traverse the canyon at various points at different levels, connecting the interior spaces. Jerde’s other projects in Japan were precedents, but Namba Parks accomplishes in a much smaller space the same intermeshing of people and spaces—of pedestrian and shopping traffic as entertainment. Indeed, its density intensifies the experience.

Rooftop terraces offer views of Namba Parks’s office tower (to the west) and the 36-story Swissôtel atop Namba station (to the north), all framed by trees and shrubs.

At the uppermost roof level surrounding the central opening—the mouth of the “canyon”—are hardscaped common areas where people can congregate outdoors. Its apex is a terraced amphitheater, circular in plan and facing a flat stage area. Nearby is the crown of the elevator tower, terminating in an inverted hemispherical finial. The underside of the hemisphere reflects a laser light show that can be programmed for different nighttime occasions and serves as a light beacon when entertainment is being produced.

Cascading down from the eighth-level rooftop is another Jerde innovation: a series of green terraces atop the roofs of the retail spaces below. Extending the canyon theme to the roof, Jerde brought the canyon-top landscape to its very precipice. Forming 2.8 acres (1.1 hectares) of rooftop park space, one of Japan’s largest, this “Big Park” is a counterpart to the “Big City” contained below in Namba Parks’s retail spaces.

The roof park features trees, miniature ponds, shrubbery, and planting beds—all irrigated by recycled water filtered from the graywater of the restaurants in the complex. During the summer, when asphalt can reach a surface temperature of 124 degrees Fahrenheit (51 degrees Celsius) and concrete is 113 degrees Fahrenheit (45 degrees Celsius), the rooftop park is only 93 degrees Fahrenheit (34 degrees Celsius).

The retail complex is of steel-frame construction, clad on all nonglazed surfaces with preformed exposed-aggregate concrete panels in banded colors reminiscent of a desert canyon. The storefronts that open to the roof terraces and those in the canyon itself feature extensive glazing.

At street level facing the already developed Namba City, Namba Parks completes the street arcade that the earlier Namba City complex began, with retail shops tucked under the overhead railroad tracks. The open-air, pedestrian-scale arcade is 46 feet (14 meters) wide and allows for vehicular traffic for maintenance and deliveries during off hours.

This northward sectional view shows the relative narrowness of the canyon as it cuts through the eight levels of retail uses above grade. At the extreme left is the elevated viaduct of the Osaka-Kobe Expressway and, at grade, Midosuji. Facing the street, the 30-story office tower provides a buffer for Namba Parks.

Standing at the street-side periphery of the complex, the 30-story office tower casts its extensive shadow most of the day on the adjacent north-south thoroughfare, thus complying with Japan’s singular sun-shadow law, which guarantees a measure of sunlight to affected buildings. Its architect, Nikken Sekkei, designed one of the biggest floor plates in Osaka—about 16,146 square feet (1,500 square meters) per floor and steel framed— using the latest in earthquake-resistant design technology. The rectilinear street facade is banded with glazing, and the curvilinear facade facing Namba Parks is clad in concrete panels with patterned fenestration.

Three levels of subterranean parking accommodate 363 cars. Like most development projects in Japan, the construction drawings and contract administration were completed by the general contractor—in this case, Obayashi.

Phase II opened in spring 2007. It is about half the size of Phase I of Namba Parks and is seamlessly contiguous with, and essentially lengthens, the canyon concept. Although the canyon in the first phase flows north, the canyon in the second phase emanates from the same source but flows south. It adds 328,200 square feet (30,500 square meters) of retail space and 0.86 acre (0.35 hectare) of rooftop green space. The major anchor is an 11-screen, 12,164-seat cinema. A residential tower developed with Oryx Real Estate stands at the southwest corner of the completed Namba Parks complex.

The retail spaces in Namba Parks are occupied primarily by popular mid- and upscale Japanese and international chains. Typical stores take up less than 3,767 square feet (350 square meters). The largest anchor, aside from the JRA off-track betting facility, is a 53,821-square-foot (5,000-square-meter) Sports Authority on three floors. Unlike in U.S. malls, Namba Parks has no food courts; for the most part, restaurants are situated to take advantage of rooftop terraces.

The entrances to the office tower and the Japan Racing Association’s off-track betting facility are at street level. The curved Carnival Street is a 46-foot-wide (14-meter-wide) pedestrian arcade serving Nankai’s Namba City shops, built under the Nankai rail tracks and the first level of Namba Parks.

The JRA’s betting facility holds a long-term lease and is managed separately from Namba Parks.

The Class A office space is 91 percent occupied, comparable with the Osaka market, which is recording 93 percent occupancy for Class A space and 90 percent occupancy throughout the city’s CBD. The tower’s rental rates represent a premium for its 28 levels of uninterrupted large floor plates (46 by 213 feet [14 by 65 meters]).

Nankai provides open-air entertainment in the rooftop amphitheater and light shows on the underside of the highly visible hemispherical elevator roof.

Nankai was able to apply lessons learned during the development of Namba Parks as it designed and built the second phase. The only area in which Nankai sought improvement was the provision of more entertainment venues at Namba Parks. The development has syner-gistically attracted more patrons to the retail-oriented Namba City and Takashimaya department store. With the additional attractions of Phase I, customers and hotel guests of the Swissôtel are inclined to spend more time at the Namba complex of developments but tend to leave the premises for entertainment venues such as cinemas and amusement parlors. This lack will be alleviated somewhat by Phase II.

| Land Use and Building Information | ||

| Site Area | 8.33 acres (3.37 hectares) | |

| Building Area | Gross Area (Square Feet/Square Meters) | Leasable Area (Square Feet/Square Meters) |

| Retail | 430,571 (40,000) | 263,724 (24,500) |

| Office | 645,856 (60,000) | 355,221 (33,000) |

| Parking | 182,992 (17,000) | N/A |

| Japan Racing Association | 236,814 (22,000) | 236,814 (22,000) |

| Floor/area ratio | 3.01 | |

| Land Use Plan | ||

| Acres/Hectares | Percent of Site | |

| Buildings | 6.9/2.8 | 76 |

| Open space | 2.2/0.9 | 24 |

| Total | 9.1/3.7 | 100 |

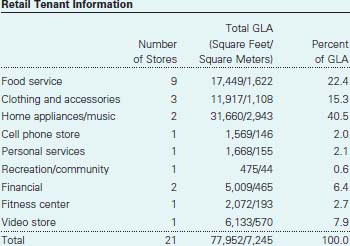

| Retail Tenant Information2 | ||

| Total GLA2 (Square Feet/Square Meters) | Percent of GLA | |

| General merchandise | 43,272 (4,020) | 16.4 |

| Food service | 56,297 (5,230) | 21.3 |

| Clothing and accessories | 53,391 (5,000) | 20.2 |

| Home furnishings | 3,875 (360) | 1.5 |

| Sports Authority | 53,821 (5,000) | 20.4 |

| Hobby/special interest | 23,251 (2,160) | 8.8 |

| Jewelry | 3,875 (360) | 1.5 |

| Other | 25,942 (2,410) | 9.8 |

| Total | 263,724 (24,540) | 100.0 |

| Average Length of Restaurant Lease 6 years | |

| Average Length of Retail Lease | 10 years |

| Average Annual Sales3 | $56 per square foot (¥65,300 per square meter) |

| Total Annual Sales | $148,000,000 (¥16,000,000,000) per year4 |

| Office Tenant Information | |

| Percent of NRA occupied | 91 |

| Under 5,380 square feet (500 square meters) | 8 |

| 5,380-10,764 square feet (500-1,000 square meters) | 3 |

| More than 10,764 square feet (1,000 square meters) | 12 |

| Tenants | 23 |

| Average Tenant Space | 14,166 square feet (1,316 square meters) |

| Annual Rents | $68.25 per square foot (¥79,860 per square meter5 |

| Average Length of Lease | 7.4 years |

| Typical Lease Term | 10 years |

| Development Cost Information | |

| Total Development Cost | $552,840,000 (¥60,000,000,000) |

Developer

Nankai Electric Railway Co. Ltd.

1-60, Namba 5-chome, Chuo-ku

Osaka, Japan

Takashimaya

1-5, Namba 5-chome, Chuo-ku

Osaka, Japan

Architect of Record/General Contractor

Obayashi Co. Ltd.

4-33, Kitahama-Higashi, Chuo-ku

Osaka, Japan

Architect (Retail)

The Jerde Partnership

913 Oceanfront Walk

Venice, California 90291

Nikken Sekkei

4-6-2 Koraibashi, Chuo-ko

Osaka, Japan

| Development Schedule | |

| 11/1997 | Planning started |

| 11/1999 | Construction started |

| 8/2003 | Phase I completed |

| 10/2003 | Sales/leasing started |

| 4/2007 | Project completed |

Notes

1 Excludes underground parking and betting facility.

2 Numbers may not add because of rounding.

3 Currency conversions based on ¥1 = $0.00912188.

4 Does not include 237,000 square feet (22,000 square meters) leased to Japan Racing Association (off-track betting facilities), which held a preexisting longterm lease.

5 Includes common service fee.

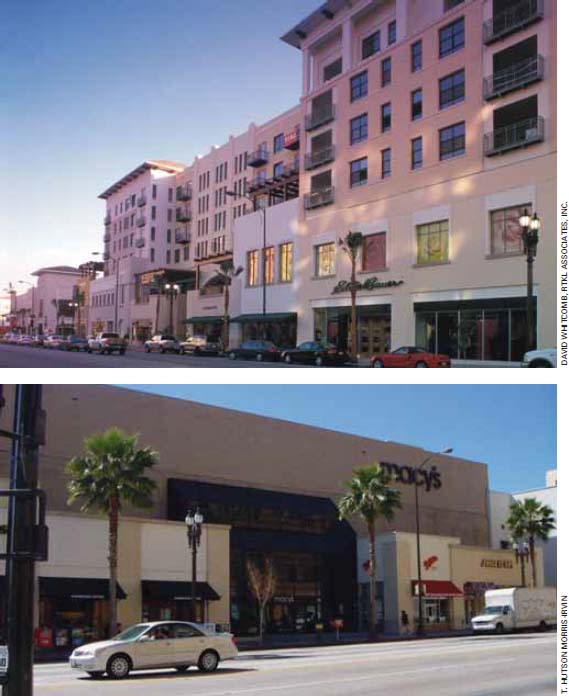

Starting in 1940 with completion of the Arroyo Seco Parkway, the first freeway on the West Coast, Pasadena transformed itself from a pedestrian-friendly town into an automobile-dependent community. Paseo Colorado is part of a coordinated citywide effort to return Pasadena to its walkable roots. Developed by TrizecHahn Development Corporation, with Post Properties as the residential developer, the three-square-block “urban village” replaces an earlier enclosed mall built as part of a 1970s redevelopment effort. Both the old mall—Plaza Pasadena—and the new center—Paseo Colorado—were developed as public/private partnerships, with partial financing and other support from the city of Pasadena.

Paseo Colorado, built on top of the previous mall’s two-level underground parking structure, mixes retail space, restaurants, entertainment uses, and housing. The project includes 56 retail shops, a full-line Macy’s department store, seven destination restaurants, six quick-service cafés, a health club, a day spa, a supermarket, a 14-screen cinema, and 387 rental housing units.

Paseo Colorado is located in Pasadena’s Civic Center district, between Old Pasadena to the west and the Playhouse District and the post-World War II Lake Avenue retail area to the east. The central focus of Pasadena’s Civic Center is Garfield Avenue. The avenue runs through Paseo Colorado, but access is limited to pedestrians. On the other side of Green Street, Paseo Colorado’s southern border, is the Pasadena Civic Auditorium. On the north side of Colorado Boulevard, Paseo Colorado’s northern border, are City Hall and the main library. These three buildings (each an example of California Mediterranean architectural style) form a view corridor designed in 1925 at the height of the City Beautiful movement.

Within a half mile (0.8 kilometer) of Paseo Colorado are two light-rail stations along the Los Angeles Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Gold Line. The Memorial Park station is to the northwest of Paseo Colorado, the Del Mar Station to the southwest.

The project faces Colorado Boulevard, a major commercial thoroughfare linking Old Pasadena, the Civic Center, the Playhouse District, and the Lake Avenue retail area. The design and siting of Paseo Colorado follow the city’s plans to make Colorado Boulevard an inviting pedestrian link that encourages more people to walk to Pasadena’s attractions.

As retail stores shifted eastward during the 1950s and 1960s from Old Pasadena to Lake Street, much of the Colorado Boulevard retail property between those districts began to decline. In an attempt to revitalize Colorado Boulevard in the 1970s, the city pursued what was then a progressive idea: building an enclosed regional mall downtown. Through its redevelopment agency, the city acquired 14.9 acres (6 hectares) of land along Colorado Boulevard and adjacent streets for the project that came to be known as Plaza Pasadena. As part of this effort, the city demolished 35 structures (some considered historic), relocated 122 businesses and individuals, constructed public improvements including parking, and sold the air rights at a highly subsidized rate. To finance the redevelopment agency’s expenditures, $58 million in tax increment bonds was sold.

The Paseo links Garfield Promenade on the west with Macy’s on the east. A curving interior walkway, it ranges from 18 to 43 feet (5.5 to 13 meters) wide and is lined with smaller shops.

Buildings facing the street sit right at the property line on Colorado Boulevard, a major commercial thoroughfare. The blank facade of Macy’s, the only original building left in place, was set back sufficiently to allow the facade line to continue.

The 600,000-square-foot (55,800-square-meter) Plaza Pasadena, which opened in 1980, was in all respects, except its location, a suburban mall. With three department store anchors (Broadway, May Company, and JCPenney), the mall was almost completely inward looking, leaving a two-block-long retail dead zone along Colorado Boulevard. Though built with the best intentions, the mall was perhaps the worst possible intervention from an urban point of view. In addition to severing the pedestrian and retail continuity of Colorado Boulevard, the mall closed off Garfield Avenue, a key north-south street. Previously, the vista down Garfield Avenue terminated at the historic central library at one end of the street and the Pasadena Civic Auditorium at the other. In the Plaza Pasadena plan, the grand axis was replaced with a glass entry wall, signifying the axial view that was lost. And in place of the beaux arts and Mediterranean-style structures that preceded it, the new mall presented a mostly blank brick facade to the street.

The introduction of Plaza Pasadena to the downtown streetscape coincided with—and in some manner was responsible for—the growing historic preservation movement in Pasadena. Through the 1980s and 1990s, Old Pasadena came back to life through the efforts of building owners and developers and the substantial public investment in parking and other improvements. While Old Pasadena prospered, however, Plaza Pasadena began to decline. And as Old Pasadena’s tax revenues steadily increased, Plaza Pasadena’s tax contributions withered as the center struggled to remain competitive. Overall, according to calculations prepared by the city’s former development administrator, Marsha Rood, although the city’s $28.8 million investment in Old Pasadena has netted approximately $400 million to $500 million in private investment ($14 of private investment for every $1 of city funds), the city’s $58 million investment in Plaza Pasadena netted only $40 million in private investment, or $2 of private investment for every $3 in public investment. In addition, the deadened streetscape along Colorado Boulevard was clearly an impediment to the regeneration of the Civic Center area and the Playhouse District just to the east.

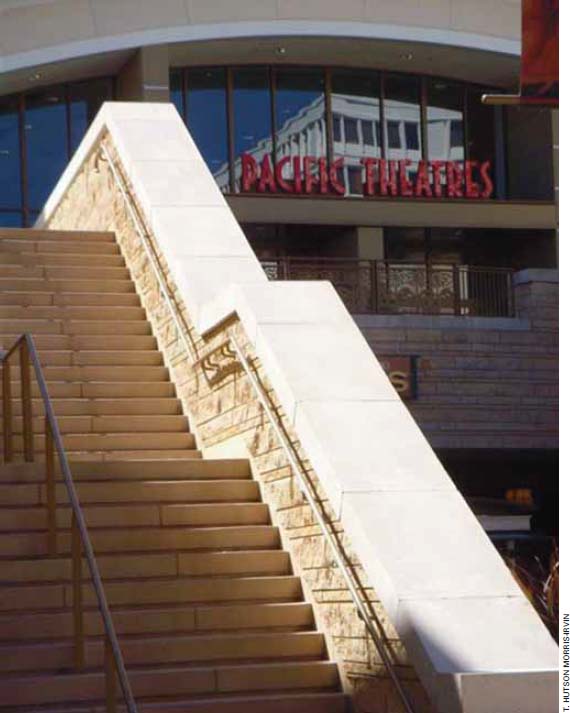

Grand staircases on either side of the street-level passageway to the Paseo lead from Colorado Boulevard to the second-level cinema. An office building across the street from Paseo Colorado is reflected in the cinema’s windows.

To address these and other issues, the city formed the Civic Center Task Force in 1997. The task force formulated several objectives for the Plaza Pasadena site: 1) restore the city street grid, in particular the Garfield Avenue view corridor; 2) reintroduce retail activity to Colorado Boulevard; 3) provide for pedestrian circulation and gathering spaces; and 4) offer a mix of uses, including housing as well as retail. The TrizecHahn Development Corporation, which, through its forebear, the Hahn Company, had an ownership interest in Plaza Pasadena, participated in the task force’s deliberations.

TrizecHahn was both philosophically attuned to the task force’s objectives and economically inclined toward the city’s recommendations. “We were sitting on gold,” notes Jennifer Mares, general manager of Paseo Colorado, referring to the site’s 3,000-plus parking spaces and the key location of Plaza Pasadena, “but renovation for retail alone just didn’t pencil out.” TrizecHahn therefore sought an experienced urban housing developer, ultimately selecting Post Properties of Atlanta.

Euclid Court, at the west end of the Paseo, offers an intimate outdoor space and surrounds the interior entrance to Macy’s with Paseo-level retail shops and upper-level apartments. A canopy covers the escalator leading to below-grade parking.

As the project was structured, the city of Pasadena contributed $26 million in financing to the project in the form of certificates of participation backed by the lease on the center’s parking structures. TrizecHahn maintains an ownership interest in the air rights above the parking, and Post Properties owns the air rights above the two-level retail podium.

The two levels of retail space were constructed on top of the concrete parking garage, maintaining to the greatest extent possible the same structural grid as the garage. Above the retail construction, the residential portion sits on its own concrete base, which is raised four feet (1.2 meters) above the retail roof. This separation allowed for the routing of utilities horizontally in the four-foot (1.2-meter) plenum space.

The concept for Paseo Colorado, which entailed the demolition of everything above the subterranean parking structure except the Macy’s department store, is described as an urban village. Based on a design by Ehrenkrantz Eckstut & Kuhn Architects, the project is divided into several neighborhoods that respond to its urban context and mixed-use program. Inspired by Old Pasadena, Paseo Colorado has both street-fronting retail space on Colorado Boulevard and interior block walkways lined with more intimately scaled shops.

Although the old Plaza Pasadena was set back from the street in a more suburban style of planning, Paseo Colorado is built right up to the street-facing property line. In a bit of good fortune, the blank brick facade of the Macy’s store was set back sufficiently to allow new shops to be built in front, thus continuing the facade line of Paseo Colorado and providing an additional increment of street activity.

Perpendicular to Colorado Boulevard, Garfield Avenue has been opened up once again, this time as Garfield Promenade, a 77-foot-wide (23.5-meter-wide) pedestrian walkway. Flanked by formal plantings and period light fixtures, the promenade restores the intent of the 1925 City Beautiful plan and reveals the previously hidden vista to the Civic Auditorium. Freestanding kiosks and retail storefronts activate the linear space, which is anchored by a mosaic-tiled fountain by artist Margaret Nielsen.

The lower-level plaza sits at the juncture of the Paseo and Garfield Promenade. More than two-thirds of the project’s 387 housing units overlook the second-level Fountain Court and its destination restaurants and outdoor dining terraces. Access between the residential and retail areas is strictly controlled.

From Garfield Promenade, a grand stairway leads up to the Fountain Court, a second-level plaza with destination restaurants and outdoor dining terraces. Most of Paseo Colorado’s housing is located in a mid-rise block overlooking Fountain Court.

The interior mid-block walkway is called the Paseo. Running parallel to Colorado Boulevard, the Paseo is a slightly curving walkway connecting Garfield Promenade and Fountain Court on the west to Euclid Court and Macy’s on the east. The Paseo varies in width from 43 feet (13.1 meters) at Garfield Promenade to just 18 feet (5.5 meters). The narrow Paseo results in a more intimate space, and the curving plan invites exploration, as one end cannot be seen fully from the other.

A cinema multiplex anchors the second level of Paseo Colorado. The theater has its own forecourt and plaza fronting on Colorado Boulevard; two grand stair ways lead up to the box office and theaters. The theaters are connected through second-level walkways to Paseo Colorado’s food court and restaurants.

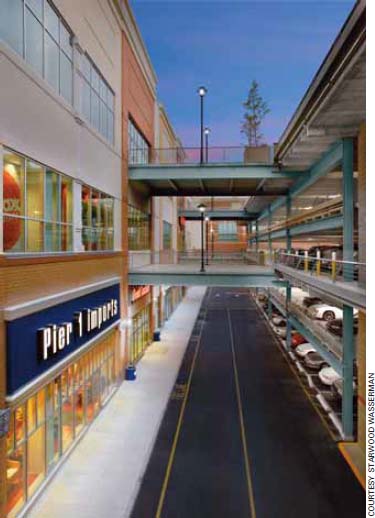

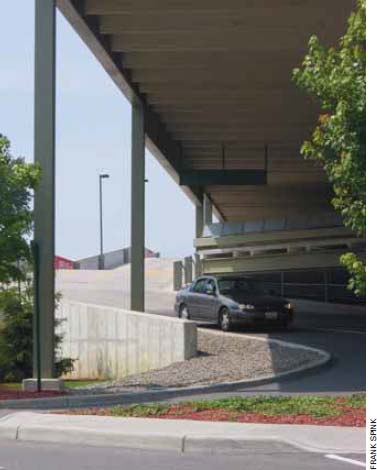

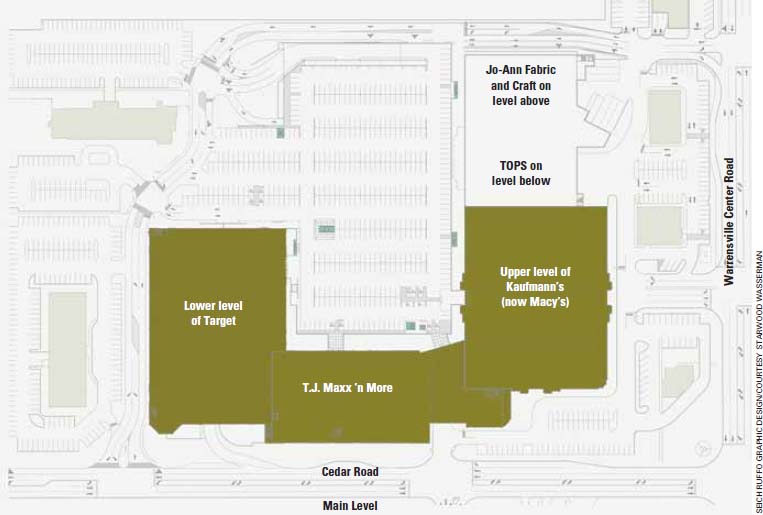

Three parking structures totaling more than 3,000 parking spaces serve Paseo Colorado. The largest is the two-level below-grade structure; the other two, which were also part of the Plaza Pasadena project, are located across the side streets from Paseo Colorado and provide direct access to the second level of Paseo Colorado via pedestrian bridges over the street. The three garages were substantially upgraded with the funds from the city. The garage beneath Paseo Colorado required localized strengthening to support the weight of the new project and seismic strengthening as well. New lighting, signage, and elevator/escalator access were also provided. The garages are all owned and operated by the city of Pasadena.

The 387 Paseo apartments are grouped into two structures. The larger building, which includes 276 luxury apartments, overlooks Fountain Court. The second structure, which overlooks Euclid Court, contains 111 loft-style units. Apartment types include studio, one-bedroom, and two-bedroom units, but because of the articulated massing of the residential towers, RTKL, the architects responsible for the residential design, had to develop more than 90 individual floor plans.

The residential units are well appointed, with ten-foot (3-meter) ceilings, open floor plans, and balconies. Black-on-black appliances and counters, polished concrete floors, industrial-type lighting, and brick accent walls lend contemporary style to the units. The project includes eight rooftop courtyards with amenities ranging from a swimming pool to barbecues to an outdoor fireplace. Units on the higher floors offer views of the San Gabriel Mountains, Pasadena’s beaux arts city hall, the Civic Center, and the plazas of Paseo Colorado. One of the courtyards overlooks the Rose Parade route, and others overlook the Civic Auditorium. Residents can enjoy the restaurants, shops, and cinema, which are all within short walking distances. An upscale supermarket, located at the street level beneath the housing, includes a coffee bar, a sushi bar, and outdoor dining tables.

The developers of Paseo Colorado and their designers sought to re-create not only the more intimate scale of the old city but also the textures and materials of Old Pasadena. Prospective tenants receive two very detailed publications that convey this concern for appropriate materials. The first, Athens of the West, Pasadena Style, is a coffee table-style book with full-color images on glossy paper that details the Pasadena heritage, the design objectives for each Paseo Colorado neighborhood, and development standards for storefronts, signage, and similar elements. The second publication, a paperback titled Craftsman’s Journal, provides additional technical criteria and contacts for artisans and artists. The introduction to Craftsman’s Journal describes TrizecHahn’s philosophy and objectives: “The creative contributions of individual tenants are critical to Paseo Colorado’s success in creating an environment where the visitor feels a tangible sense of place. Each merchant will be required to creatively alter or adopt [his or her] predetermined design concepts to meet the specific existing conditions.”

Stylistically, Paseo Colorado reflects Mediterranean design motifs and materials, though in a more modern idiom. Facades are finished in smooth plaster and colored in various earth tones and pastels. Decorative lighting includes modern and art deco light standards as well as Craftsman-style lanterns strung across the Paseo, providing a canopy of light. Custom-designed and -fabricated art elements are evident throughout the project, ranging from delicate floral patterns in the stair and guard railings to a tiled fountain with mosaic “postcards” of Pasadena.

The relationship between the residential and commercial areas of Paseo Colorado has been carefully considered and controlled. Three residential lobbies have been created at the street level (two for the luxury apartments and one for the loft-style building), separated from the access to the commercial areas. Parking is similarly segregated: residents park in a physically separated section of the lower level of the two-story subterranean garage and have card keys to access the express lanes of the garage entries. The garage has 494 assigned parking spaces for the 387 dwelling units, or 1.3 spaces per unit. For security, garage elevators serving the residential portion of the project do not stop on the retail levels, and retail access elevators do not allow access to the apartments. To facilitate access from the apartments to the restaurants and other areas of Paseo Colorado, however, stairs with electronically controlled gates are provided from the lower level of the housing to Fountain Court and Euclid Court.

Loading is also controlled. Six loading docks, located on a side street, serve Paseo Colorado. Four of the docks are dedicated to the retail/restaurant portions of the project, and the remaining two serve the housing and the supermarket. These two bays are further controlled by hours of use; the supermarket accepts deliveries in the early morning hours, and the apartments have access to the docks between 10:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m.

Noise levels are controlled in several ways. Operating hours for restaurants with outdoor dining terraces end at midnight on weekdays and 2 a.m. on weekends, and loud music is prohibited. Noise limitations are similarly written into the residential leases, and the pool deck, which sometimes can be noisy, has been located away from Fountain Court to preclude disturbances.

Retail leasing for Paseo Colorado was complicated by the fact that the city of Pasadena had political and financial interests in the adjacent retail areas of Old Pasadena, the Playhouse District, and Lake Street. The city’s mandate to TrizecHahn, in effect, was to provide an active and successful mix of retailers but not to steal from other Pasadena venues. In addition, the competition facing Paseo Colorado included two successful regional malls in nearby communities. And although Old Pasadena was a proven success for retailers, the Paseo Colorado location had not been successful, and the concept of an urban village was somewhat new to the retail community.

The developers of Paseo Colorado could look to four complementary market strengths, however, to offset these constraints: a large primary trade area (941,000 persons within a radius of 7.5 miles [12 kilometers]); a daytime office market within walking distance; a visitor/tourist market (including the adjacent Pasadena Conference Center); and the planned on-site residential market and a growing nearby residential base. Playing to these multiple markets, Paseo Colorado has pieced together a roster of tenants that fulfills the objectives of creating an active, mixed-use destination while not duplicating (or stealing) tenants from nearby retail areas. Macy’s, the one tenant to remain from the original mall, invested approximately $1 million to remodel its store, converting the space from a discount outlet to a full-line store.

Residents were attracted to the urban lifestyle that Paseo Colorado affords, especially the convenient shopping and entertainment opportunities. Moving in from Pasadena and surrounding communities, the residents are mainly singles and couples ranging from young professionals to empty nesters. Tenants of the loft-style apartments are younger than the tenants of the conventional units.

One attraction of Paseo Colorado for both retailers and patrons, notes Mares, is the “village experience.” The developer is working to create a “marriage between retailers and residents not unlike the friendly, first-name-basis lifestyle of a traditional village.” To that end, “community teas” were held during planning of the project to acquaint people with the developer’s concept. The results of the teas were shared with prospective tenants to make sure they understood and would advance the project’s broader objectives. Similarly, the security guards who patrol Paseo Colorado are called “public safety ambassadors” and are trained to approach and assist visitors while making eye contact.

Since the project opened in early 2002, retail sales have exceeded expectations, notes Mares. Several tenants are posting sales that place them near the top of their outlets nationally. Brand-name lines are doing especially well, while the public is just discovering some of the newer tenants. The mixture of market segments and uses at Paseo Colorado appears to explain some of the success: the professional crowd supports the center Monday through Friday, says Mares, and the stroller crowd and cinema-goers round out the weekend. Sales are unexpectedly strong on Sundays, partly because of Gelson’s Supermarket.

Paseo Colorado’s success is partly the result of how its design has addressed the context, uses, and architectural styles of its surroundings. By adding to and enhancing the existing pedestrian fabric of downtown Pasadena, the developers have benefited from the synergy created by walkable mixed-use environments.

As one of the first projects to mark the sea change in public and private thinking about urban retail centers, Paseo Colorado has replaced the inward-looking mall previously built on the site with a project that reintroduces retail uses to street frontages, restores the urban block pattern and the axial view intended for the site, and provides for mixed uses and interior mid-block retail space. The success of the project is spurring proposals for development of long-neglected vacant parcels adjacent to the site.

Although substantial competition exists from nearby retail areas, Paseo Colorado appears to be forging a successful niche for itself based on its mixed and complementary uses. It taps demand from several markets, activating the project seven days a week over a wide range of operating hours.

Destination restaurants appear to be a successful anchor at Paseo Colorado. “People go to the food,” notes Mares, but the lively, festive atmosphere encourages them to stay—and to come back later.

Second-floor commercial uses can be successful, but access is critical. At Paseo Colorado, access is achieved by several grand stairways and visible second-level plazas as well as by multiple elevators and escalators throughout the project.

| Land Use and Building Information | |

| Site area | 10.9 acres (4.4 hectares) |

| Gross building area | Square Feet (Square Meters) |

| Retail/restaurants Residential | 644,942 (59,940) 397,202 (36,915) |

| Floor/area ratio | 0.86 |

| Parking spaces | 3,046 |

| Retail Tenant Information | ||

| Total GLA (Square Feet/Square Meters) | Percentage of GLA | |

| Retail | 208,387/19,367 | 37.4 |

| Restaurants | 68,470/6,363 | 12.3 |

| Health club | 24,393/2,267 | 4.4 |

| Market | 37,009/3,439 | 6.6 |

| Cinema | 66,517/6,182 | 11.9 |

| Department store | 152,547/14,177 | 27.4 |

| Total | 557,323/51,796 | 100.0 |

| Development Cost Information | |

| Site Acquisition Cost | $25,200,000 |

| Site Improvement Costs1 | |

| Demolition | $3,600,000 |

| Site work | 1,150,000 |

| Landscaping | 1,200,000 |

| Parking garages | 7,100,000 |

| Off-site improvements | 2,000,000 |

| Total | $15,050,000 |

| Retail Construction | $49,770,000 |

| Soft Costs | |

| Architecture/engineering | $7,300,000 |

| Project management | 4,500,000 |

| Marketing and leasing | 26,550,000 |

| Legal | 1,800,000 |

| Taxes and insurance | 980,000 |

| Construction interest | 8,200,000 |

| Furniture, fixtures, and equipment | 5,250,000 |

| Other costs | 2,100,000 |

| Total | $71,730,000 |

| Residential Construction | $75,000,000 |

| Total Development Cost | $236,750,000 |

Master Developer

TrizecHahn Development Corporation

Ernst & Young Plaza

725 South Figueroa Street/Suite 1850

Los Angeles, California 90017

Residential Developer

Post Properties, Inc.

4401 Northside Parkway/Suite 800

Atlanta, Georgia 30327-3057

Architect

Ehrenkrantz Eckstut & Kuhn

2379 Glendale Boulevard

Los Angeles, California 90039

Residential Architect

RTKL Associates, Inc.

333 South Hope Street

Los Angeles, California 90071

| Development Schedule | |

| 6/1998 | Planning started |

| 3/1999 | Sales and leasing started |

| 11/1999 | Site purchased |

| 6/2000 | Construction started |

| 9/2001 | Retail project completed |

| Spring 2002 | Residential project completed |

Notes

1 On and off site.

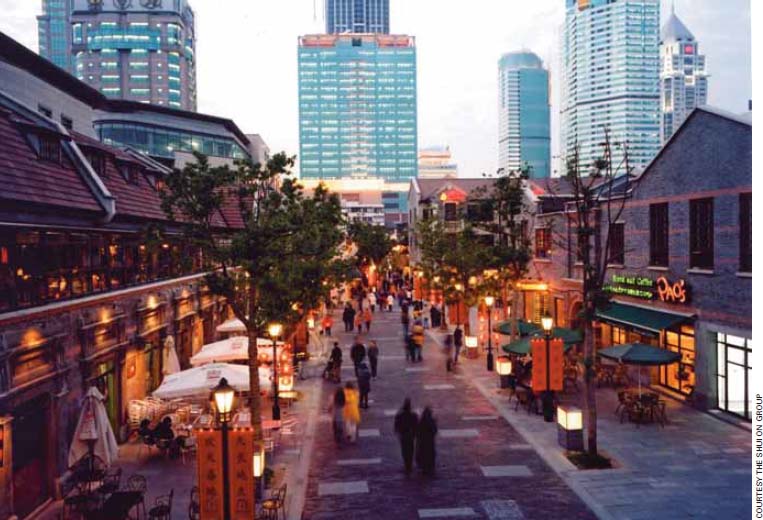

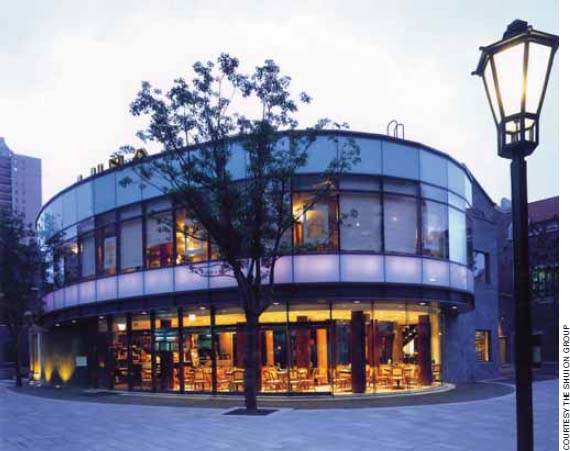

Shanghai Xintiandi—pronounced “shintien-dee” and translated “new world”—is a two-square-block complex of shops, restaurants, cultural attractions, and offices in central Shanghai. Functioning as an outdoor pedestrian mall, it is divided into two blocks. The North Block, comprising primarily restored and reconstructed historic courtyard homes known as shikumen houses, has the feel of an old Shanghai street with shopfronts and outdoor eating and sitting areas. Its walkways connect to the adjacent South Block, which is a new retail, entertainment, and hotel complex designed in a contemporary style with architectural elements and materials that complement the historic character of the North Block. Anchored by a cinema and fitness center, the South Block features a variety of shops and restaurants at its exterior perimeter as well as at its interior courtyard area. Underground parking for the development is located beneath the South Block.

The site area of the two blocks is about 7.4 acres (just under 3 hectares), the gross commercial floor area 610,100 square feet (56,700 square meters). It is part of the first phases of development of the 128-acre (52-hectare) Taipingqiao redevelopment area in downtown Shanghai being led by Hong Kong-based Shui On Land Limited, property flagship of the Shui On Group.

Shanghai Xintiandi is located in central Shanghai in a formerly low-rise residential district that is undergoing a transition to higher-density, modern development. The two-square-block site occupies the northwest corner of the Taipingqiao redevelopment area. East of Xintiandi is Taipingqiao Park, a landscaped open space that serves as the centerpiece of the redevelopment area. North of the park (and east of Xintiandi) lies Corporate Avenue, a commercial office area, and south of the park is the Lakeville luxury residential area, all components of the project. Areas to the south include older low-rise houses and shops, and areas to the west are made up of high-density apartments.

Xintiandi lies one block south of Huai Hai Zhong Road, a busy, upscale shopping street that also is the site of the nearest underground subway station. Numerous bus lines run along nearby streets.

The Shui On Group was founded in 1971 in Hong Kong by Vincent H.S. Lo. Shui On is in the real estate, construction, and cement-manufacturing businesses. In 1985, the company entered the mainland China market and has spent years building connections and investing there. To consolidate its prime developments on the mainland, the group established its property flagship—Shui On Land Limited—in 2004. The company focuses on two key business segments in mainland China: large-scale city core development projects and high-quality residential projects. The developer’s intention is to fully integrate both types of projects into urban planning schemes.

Over the past two decades, the transformation of Shanghai has been rapid. New urban infrastructure has been put into place, including an underground public transit system, elevated expressways, ring roads, and even a magnetic levitation (Maglev) rail system running between the city and the new Shanghai Pudong International Airport. High-rise offices, hotels, and residential towers have been inserted into the fabric of the old city. Across the Huangpu River to the east is the Pudong Special Economic Zone, home to dozens of new skyscrapers. One result of this massive building boom is the loss of many of the city’s low-rise neighborhoods and historic buildings.

Shanghai Xintiandi functions as an outdoor pedestrian mall, divided into two blocks. The North Block, in the foreground, features rehabilitated historic courtyard houses serving as shops and restaurants, and the South Block contains a retail, entertainment, and hotel complex designed in a contemporary style. These two blocks are the northwest corner of the Taipingqiao redevelopment area, undertaken by Shui On Land. To the east of Xintiandi is Taipingqiao Park, which serves as the centerpiece of the redevelopment area.

During the late 1990s, the Luwan district government in Shanghai asked various developers to submit development concepts for a large area in the center of the city. The Shui On Group subsequently received the rights to develop this 128-acre (52-hectare) area. Known as Taipingqiao, this redevelopment area is planned to include a mix of commercial and residential buildings focused around a 10.9-acre (4.4-hectare) landscaped park and manmade lake. Major components of the district include the already completed Xintiandi North and South blocks, Corporate Avenue, Class A office buildings, an entertainment and commercial complex, and Lakeville, a 44.5-acre (18-hectare) luxury residential area. Ten office buildings are planned for Corporate Avenue; two office structures with a gross floor area of 840,000 square feet (78,000 square meters) have been completed and are fully occupied. The first phase of Lakeville features three low-rise apartment buildings, two towers, and villas. In 2005, sale prices of $5,000 per square foot ($53,800 per square meter) were achieved there, the highest residential prices paid to date in Shanghai.

The San Francisco office of U.S. architecture firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill created a master plan to guide development of the Taipingqiao redevelopment project. Previously, the Xintiandi area housed some 2,300 families totaling more than 8,000 people. The Luwan government, with $75 million from Shui On, assisted in the relocation of a large number of these residents.

Several factors led to the concept for Xintiandi. Because a national historic site (the former school where Mao Zedong held the first Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in 1921—now a museum) is located in what is now the center of the district, the local government required that the developer preserve the building and limit the height of new construction in the immediate area. In addressing these requirements, the Shui On Group realized that it needed to create a distinctive project that would not only attract a market on its own but also raise the value of land in the surrounding areas that it controlled. When the Boston-based architectural firm Wood + Zapata was brought on board in 1998, it was proposed that the original buildings surrounding the historic shrine be maintained and reused as much as possible, the concept that became the basis for the project.

Xintiandi’s shikumen-style (“stone gate”) houses are a unique form of Shanghai residential architecture that developed during the 1860s in response to an influx of a large number of refugees from outside Shanghai into the city’s foreign settlement areas. To accommodate these new residents, real estate developers of the period erected rows of shikumen homes on an unprecedented scale.

Built in a dense courtyard configuration, these attached rowhouses were accessed by narrow alleys. Generally standing three stories tall, many featured elaborately carved stone frames surrounding a heavy wooden door. European ornamentation borrowed from the city’s colonial architecture was combined with Chinese design, layout, and materials to create an eclectic housing style. Though largely constructed as single-family units, the homes became more crowded over the years, sometimes housing multiple families who shared kitchens and bathrooms.

To determine which structures could be saved and which had to be rebuilt, nearly a year was spent inventorying every building on the North Block site. Preserving every historic edifice in the area was not feasible because of poor building conditions and prohibitive preservation costs; the need to install new systems for power, water, sewage, and fire prevention also presented serious challenges to the preservation efforts. In addition, the original density of the block needed to be opened up with spaces to allow access to shops and areas for outdoor events and dining. In many cases, structures were so severely deteriorated that the developer and architect opted to rebuild them using portions of the original facades and significant architectural features such as the stone doorway frames, wooden windows, and exterior walls. Even in cases where partial preservation was possible, it was necessary to replace old timber structures with steel. The original bricks and tiles that were reused had to be treated with special agents to strengthen them and prevent corrosion.

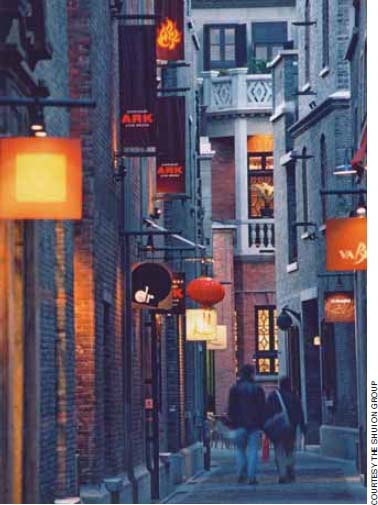

Built in a dense courtyard configuration and accessed by narrow alleys, the shikumen-style (“stone gate”) houses of the North Block are a distinctive form of Shanghai residential architecture that developed in the 1860s and blended colonial European ornamentation with Chinese design, layout, and materials.

Because the old houses lacked basic utility services, it was necessary to dig deep trenches under every building to lay water supply and drainage pipes, sewage treatment systems, gas pipes, electric lines, and telecommunication cables. With very little room for heavy machinery, workers had to install these new systems by hand.

In the North Block, the combination of old and new construction resulted in a cleaned-up version of the old shikumen neighborhoods. The narrow alleyways in the North Block were retained and paved with the same gray flagstones originally used in the area.

Converting the structures to commercial use has involved combining modern materials and architectural features with the traditional style. At the ground-floor level, for example, large glass doors and panels have been used to open up the interior spaces and allow visitors and shoppers to see inside. At the western boundary of the North Block, two new modern four-story office buildings were inserted into the block. Facing outward to the street to the west, they have little functional or visual connection with the historic architecture on the remainder of the site.

Some of the original density of the North Block was opened up with spaces to allow access to shops and areas for outdoor events and dining. This view looks north.